Between 2007 and 2010, the provincial KwaZulu-Natal Regional Land Claim Commission (KZNRLCC) purchased several farms in an attempt to settle land claims in the Lower Mpushini-Lion Park area in Mkhambathini, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. They awarded the land to the Azibuye Emasisweni MaQamu Community Trust (AEMCT), with Inkosi Siphiwe Michael Majozi as founder and trustee. Over the next decade, a protracted battle for control of the awarded land and the settlement of the remainder of the claim unfolded around several factions of claimants and beneficiaries. The Mchunu family had also lodged claims under the Restitution of Land Rights Act 22 of 1994 for the same farms. When Majozi, a leader of the Qamu chiefdom descended from colonially-appointed landless chiefs, began to sell access to residential sites on the land, the Mchunu family took to the courts to contest the award. As news coverage of the conflict—which at times threatened violence—spread in the press, Majozi defended his claim to the land based on history: “My family and kingdom have been here since the 1800s” (Magubane Reference Magubane2011). How did a historically landless chief draw upon colonial and apartheid concepts of traditional authority to acquire land in the post-apartheid era?

The Mchunu also set out to defend their claims in terms of history, positioning themselves as firstcomers in the region dating to the reign of King Shaka (1816–1828). The area was then on the fringes of the Zulu kingdom, geographically, politically, and socially. It is a region about which tales of amazimu, or “people who eat up others,” proliferate. These accounts use the political idiom of “eating up” to warn of the dangers of existing outside the centralized authority of a chief or king. While the work of Carolyn Hamilton and John Wright has done much to unpack the stereotypes that are embedded in historical accounts of so-called cannibalism and about Shaka’s armies moving in waves through the region that are embedded in historical accounts (Hamilton Reference Hamilton1998; Wright Reference Wright1991), these narratives shape the oral accounts that tie the area’s people to the land. When deployed in land claims such as that at Mpushini-Lion Park, these tales operate as what Carola Lentz (Reference Lentz2013) has described in west Africa as oral land registries that connect people to land and to one another in a region that white settler myths depict as empty land.

While the state building of King Shaka and his predecessors in southeast Africa involved migrations, the contested farms—sub-divisions of Spitzkop/Zandfontein, Vaalkop/Dadelfontein, Doornhoek, Ockertskraal, Dalkeith, Langehoop, Mpushini, and others—have a long history of African occupancy, even after British officials registered them in the name of settlers after the annexation of the Natal Colony in 1843. The arrival of Boer trekkers and the British brought new conceptions of land—trekker transhumance and British-bounded private property—to a region with its own principles of first use and reciprocal rights to land. Across several decades, British administrators established “locations” or “reserves” intended for African residents under the authority of chiefs and headmen; this would become the system of “native administration” under what scholars debate as “limited rule” and “indirect rule” in Natal (McClendon Reference McClendon2010; Guy Reference Guy2013). The government also made grants of Crown lands to immigrants (private lands). An 1874 estimate suggested that at least five million acres of Natal land privately owned by Europeans or land companies were actually occupied by Africans paying in rent or labor (Slater Reference Slater1975:272). This continued in the Union of South Africa, beyond the 1913 Land Act that aimed to maintain existing land patterns by delineating boundaries of the locations, defining additional “scheduled areas” under the control of the South African Native Trust for addition to the locations, and forbidding African purchase of land outside of these areas (Beinart & Delius Reference Beinart and Delius2015:24–25). Throughout the twentieth century, officials, white land owners, and rent-paying African tenants put these farms forward for addition to the reserves under the 1936 Land and Trust Act and, during apartheid, under the KwaZulu bantustan.

During this time, some African families managed to maintain homesteads on Spitzkop/Zandfontein and Vaalkop/Dadelfontein while others moved on and off the farms, sometimes from one to another, forced by laws that privileged the rights of white farm owners. The 1913 Land Act did curtail some forms of tenancy on white-owned farms, but the 1936 Native Land Act required tenants to work for landowners rather than pay rent. The 1951 Prevention of Illegal Squatting Act enabled camps to house those forced off farms, and the 1963 Bantu Laws Amendment Act further conscribed tenancy (Wotshela Reference Wotshela2019:8). The offices responsible for administering tenancy, removals, and location and trust lands to which people were removed found themselves overwhelmed by the 1940s and 1950s (Mager Reference Mager1999).

South Africa’s post-apartheid land reform agenda aims to address these historical discriminations. The agenda includes three main programs: redistribution of land, restitution to those dispossessed, and tenure reform. Bernadette Atuahene posits these as dignity restoration provisions, designed to reintegrate dispossessed populations into society (Reference Atuahene2014:57). But much of the literature on post-apartheid land reform reveals the limitations of the programs—in terms of both design and implementation. Studies highlight issues of individual rights to communal land, gendered access, the tension between neoliberal policies and the redistribution of resources, agricultural productivity, and failed business models (Walker Reference Walker2002; Claassens & Cousins Reference Claassens and Cousins2008; James Reference James2007; Walker Reference Walker2008; Fay Reference Fay2009).

Policymakers intended restitution to be a limited process to redress dispossession resultant from historical racially discriminatory legislation. They stressed that restitution would be largely for post-1948 dispossession, prioritizing certain kinds of loss. Through both restitution and redistribution, the state failed to meet its goal of transferring 30 percent of the land by 2014; of the 8 to 9 percent transferred, scholars question how well these awards actually addressed poverty reduction (Hall Reference Hall, Cousins and Walker2015; Walker Reference Cousins and Walker2015). Ruth Hall and Thembela Kepe (Reference Hall and Kepe2017) argue that widespread criticism of this slow pace of land reform obscures the extent of the crisis. Restitution aims “became confused with the broader aims of redistribution, which put pressure on the [Land Claims] Commission to resolve complex claims quickly” (Beinart, Delius, & Hay Reference Beinart, Delius and Hay2017:3).

There was no one moment when land loss occurred during colonialism and apartheid; rather, dispossession was an ongoing process that took many forms. In the Lower Mpushini-Lion Park area, families like the Mchunu—around whom an anti-Majozi faction have formed—found themselves resident on settler land, increasingly subject to rent, labor, and livestock restrictions. Chiefdoms were created and destroyed at moments when colonial officials sought to move chiefly authority from “by the people” to “by the land” (Kelly Reference Kelly2018; Ngonyama Reference Ngonyama2012). Cherryl Walker and Ben Cousins use the formulation of “layers of overlapping and competing land rights” to recognize that many families and individuals experienced multiple dispossessions. Adjudicating these rights has been one of the major problems facing post-apartheid government (Cousins & Walker Reference Cousins and Walker2015:13–14; Walker Reference Walker, Divided and Restored2015). Michelle Hay’s work shows the disjuncture between neat government suppositions of a history with timeless chiefs holding the land and historical evidence that reveals multiple kinds of rights and claims to land. In its complexity, the history at Lower Mpushini-Lion Park is more akin to what Hay has described in the Letaba District of Limpopo as “a tangled web of unique family histories” (Hay Reference Hay2014:759). These diverse family histories underscore the power of firstcomer stories that flout complexity.

But the land is not only desirable on account of these complex, layered historical ties. The farms are situated in the Mkhambathini and Msunduzi municipalities, off of the N3 highway that runs between the port of Durban and the industrial center of Johannesburg—one of the country’s most trafficked arteries.Footnote 1 In the 1990s, “development corridors” became popular in provincial development planning. KwaZulu-Natal identified this corridor as one area of growth. The province argued that land reform should occur near such corridors to improve access to markets (Harrison & Todes Reference Harrison and Todes1996). Development in the region has grown, as suburbs extend outward from the provincial capital of Pietermaritzburg. As one landowner explained, the vision of the N3 corridor persists, even as earlier development plans have fallen through.Footnote 2 The farms include a hotel, quarry, nature reserve, and chicken hatcheries. Claimants recognize the land as a historical dispossession and the burial place of family, but they are also aware of its potential for financial gain with respect to tourism, leasing, and sale of access to land. (See Map, Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map showing location of farms. Source: Chief Surveyor General of South Africa

Sara Berry (Reference Berry2017) argues that it is important to recognize struggles such as this over land and authority in Africa “as dynamic processes, taking account of the way levels of authority, political contests, and forms of land access and use have come together in specific contexts.” While the Lower Mpushini-Lion Park claim is representative of many of the trends identified in the literature on land reform in South Africa—benefits to traditional leaders, widespread corruption, and the limits of state institutions to address irregularities—analysis of this claim introduces two new factors. The article documents the initially successful restitution claim of the descendant of a colonially appointed chief who never had a chiefdom defined by territory to be dispossessed of. While scholarship on traditional authority and land across the continent documents growing chiefly power over land, this was a chiefdom without land whose recent leader invoked colonial-era forms of landed authority to his personal financial benefit. Central to understanding how a landless chief came to be landed requires an elaboration of several forms of chieftaincy that were promoted in colonial Natal by British authorities.

The case at Lower Mpushini-Lion Park also sheds new light on how actors deploy histories in a manner distinct to the KwaZulu-Natal region as part of the land restitution process. The descendant of a colonially appointed chief used narratives of landlessness and promises of land that merged personal and chiefly land. The descendants of those historically on the margins of the Zulu kingdom called on autochthonous histories of King Shaka and the dangers of existing outside of the kingdom. At Lower Mpushini-Lion Park, oral narratives about the Zulu kingdom and the onset of colonial rule in Natal shaped the contestation of the claim as well as control of the awarded land.

This article draws on press coverage of the claim, archival records about the farms and chiefs, recorded oral accounts, and additional documents compiled from several incomplete sources to unpack the historical accounts of the Majozi and the firstcomer narratives of the Mchunu. I did not consider the tenancy records of every farm under dispute—which would be the responsibility of the officials and consultants investigating the claim—only those on which Majozis resided, in order to investigate their historical claims. I also pursued additional oral accounts, but the highly contested nature of the land claim made many of those involved fearful to speak.Footnote 3 Others have ceased pursuing interviews due to the perceived danger (Whelan Reference Whelan2018). This means that this article sheds less light than one would hope on the contemporary motives of the chief’s supporters. The late Inkosi Majozi recorded his historical interpretations and shared purposes with the press, but these must be recognized as only partial motivations, given the real economic profits he and his successors stood to gain from the potential value of the land.

The History of Land and Authority

The Lower Mpushini-Lion Park land restitution case is entangled with post-apartheid South Africa’s recognition of traditional authority. Across the continent, British colonial officials sought to efficiently administer African populations that outnumbered them by drawing authority from existing political structures. Where authority was needed, because such authority was absent or uncooperative, British officials appointed new chiefs.Footnote 4 While historically, access to rights to land was dependent on agreements between figures of authority or institutions and their followers, colonial authorities promoted territorial authority over such social contracts, gradually giving chiefs greater power over the administration of land.Footnote 5 In South Africa, colonialism and apartheid turned fluid polities into territorially bounded tribes (Landau Reference Landau2010; Ngonyama Reference Ngonyama2012; Kelly Reference Kelly2018).

As Mbongiseni Buthelezi and Beth Vale argue for post-apartheid South Africa, traditional and democratic governance have mutually transformed one another and “the recognition of traditional leaders post-1994—whether as custodians of the land, mediators of disputes or champions of local development—has changed the very nature of constitutionally prescribed democracy” (Reference Buthelezi and Vale2019:2). Members of the post-apartheid ruling party acknowledged the relationship between traditional leaders and the land when they passed the Traditional Leadership and Governance Framework Act of 2003 and the Communal Land Rights Act of 2004, which gave powers of land allocation and administration in the former reserves to traditional leaders—basically on the same lines of the apartheid government (Ntsebeza Reference Ntsebeza2008). State commissions such as the Nhlapo Commission perpetuate apartheid practices that do not reflect the historical flexibility of traditional authority (Buthelezi & Skosana Reference Buthelezi, Skosana, Comaroff and Comaroff2018). Even strands of civil and liberation movements replicated forms of chiefly authority in competition for resources (Wotshela Reference Wotshela2019:14).

The ruling African National Congress adopted the original cut-off date of 1913, recognizing that earlier claims would come out of chiefly communities (Beinart, Delius, & Hay Reference Beinart, Delius and Hay2017:99). But in KwaZulu-Natal, some chiefs lodged claims early in the process, and claims have been bound up with the Zulu monarchy, particularly surrounding the emergence of the Ingonyama Trust in the last gasps of apartheid. When the former bantustans were integrated into South Africa after the 1994 elections, the land they administered came under the control of the national government, except for the new KwaZulu-Natal province. In KwaZulu-Natal, former bantustan land (including reserves neighboring the farms in question) was transferred to the Ingonyama Trust with the Zulu king as sole trustee (Lynd Reference Lynd2021). As President Jacob Zuma came to more closely ally with traditional leaders, he called on chiefs to lead efforts to claim land when the process reopened in 2014. Legislation since 2002 has benefited the elite, both traditional leaders and political party leaders, at the expense of the property rights of the majority (Claassens Reference Claassens2019). This is particularly true in the mining areas of the former bantustans, where decisions about land rights have not led to economic benefits for community members. Contested constructions of “community” have become a popular means of claiming rural resources (Mnwana Reference Mnwana, Buthelezi, Skosana and Vale2019; Capps & Mnwana Reference Capps and Mnwana2015; Turner Reference Turner2013).

Scholars have long demonstrated the primacy of land claims and boundary contests to the construction of political authority in Africa.Footnote 6 Christian Lund’s (Reference Lund2008) work reveals how changes with regard to land tenure in Ghana in 1979 opened not only struggles over land but also competition over who had authority to decide conflicting claims. In this contest and many others on the continent, the histories of one’s origins and one’s status as “firstcomers” play an important role (Berry Reference Berry2000; Delius Reference Delius2008; Lentz Reference Lentz2013; Beinart, Delius, & Hay Reference Beinart, Delius and Hay2017:108; Zenker Reference Zenker2018b). The closest parallels for Lower Mpushini-Lion Park are with other territories under British indirect rule, such as Ghana, where work has shown history, and debates about it, to be significant to making claims to land (Berry Reference Berry2000; Lund Reference Lund2008; Sackeyfio-Lenoch Reference Sackeyfio-Lenoch2014). A focus on autochthony in these histories reveals not only how actors identify with one another but also how they identify with the land (Zenker Reference Zenker2018b). Lentz’s (Reference Lentz2013) concept of the “oral land registry” posits the telling of history as a way to connect oneself to land. As Lotte Meinart and Daivi Rodima-Taylor recently argued, while autochthony remains a widely deployed claim, it is one that creates tensions and one in which questions “of where to draw the line between ‘original inhabitants’ and ‘late-comers’ always loom” (Reference Meinert and Rodima-Taylor2017:9). These “son of the soil” tensions do not always result in large-scale violence (Boone Reference Boone2017). Historical accounts deployed by the Majozi to connect themselves to the land and by the Mchunu to position themselves as firstcomers vis-à-vis settlers and the Majozi reflect the history of a growing sense of Zulu identity centered on King Shaka and colonial Natal as a space that was home to multiple forms of chieftaincies—those landed and those not.

The Making of a Landless Chief in Colonial Natal

As British officials connected chiefly authority to land, those without access to location land—the government’s designated land reserved for Africans under customary authority—came to be landless chiefs. This included Siphiwe Majozi’s ancestors who lived on white-owned farms. Siphiwe’s repeated articulation of the Qamu past reveals disconnects between his understanding of his land tenancy and the way it was understood by apartheid officials. In 1996, Siphiwe had an account of the chiefdom’s history notarized by a commissioner of oaths. This document foregrounds the Majozi historical interpretations, if not the chief’s contemporary motivations. Combined with other archival records documenting his and other Majozi visits to state officials, this material reveals how the leaders have deployed history, at times selectively, to bolster their claim to the land.

In 1974 and 1996 statements, Siphiwe refers to the removals of the “Qamu tribe” and “a section of the Qamu tribe.” This contrasts with magisterial records that document removals of homesteads; some of these homesteads included the Qamu chief and his subjects, but others listed as tenants paid allegiance to other leaders. In the 1996 document, Inkosi Siphiwe dates the Qamu in Mkhambathini [Inanda] location and farms in Camperdown and Pietermaritzburg districts to 1858, “ruled by Chief Mfulathelwa son of Ludaba Majozi” (Siphiwe Majozi, “History of Majozi Tribe,” 1996, Landholder Research Packet--LRP). He fails to detail how the first Majozi came to lead. He outlines the names and dates of his chiefly predecessors, their residency on the farms in question, and alleged government promises to make the Qamu landed.

The Majozi family from which Siphiwe descends had indeed been in the region since the earliest days of colonial Natal, but the connection between their political authority and the farms in question is much more complex than he conveyed. Siphiwe’s ancestors were iziphakanyiswa, those lifted up by British colonial officials in Natal. Secretary for Native Affairs (SNA) Theophilus Shepstone allowed some of the men who worked with him as “government indunas” to perform the duties of chiefs. Ngoza kaLudaba grew up in Zululand. In the early 1840s, he crossed into the colony, where he served as Shepstone’s induna. This position enabled Ngoza to amass wealth through fines, fees, and cattle. Ngoza, his brother Mfulatelwa, and Mqundane Mlaba set up homesteads outside of the colonial capital. Following local practices of building homesteads and relationships through ukukhonza (to pledge allegiance in return for security), Ngoza and Mqundane built up two of the largest and most heterogeneous chiefdoms in the colony of Natal in the 1860s, the amaQamu and amaXimba (Kelly Reference Kelly2018:36–40). Both colonial officials and Africans recognized the distinction between iziphakanyiswa and those deemed to be hereditary chiefs. Natal administrators saw these differences as antagonistic and therefore of value when it came to administering African populations. While those recognized as hereditary chiefs and their subjects dismissed iziphakanyiswa, those who pledged allegiance to these new leaders did so by customary means of recognizing authority in return for expected benefits (Kelly Reference Kelly2018:30).

Ngoza remained close to Shepstone and, in 1858, moved north to land made available by him (McClendon Reference McClendon2010:72). Some of Ngoza’s followers joined him in Msinga, the place now considered by Siphiwe’s detractors as the “real” home of the Qamu. Others remained behind under Mahoiza Mkhize, another who used his service with colonial offices to become isiphakanyiswa (McClendon Reference McClendon2010:82–99). But by 1880, most viewed Mahoiza only as a representative of Ngoza’s heirs. Factions began to coalesce around Manyosi Gcumisa and the son of Mfulatelwa (Ngoza’s brother), Mbobo Majozi.

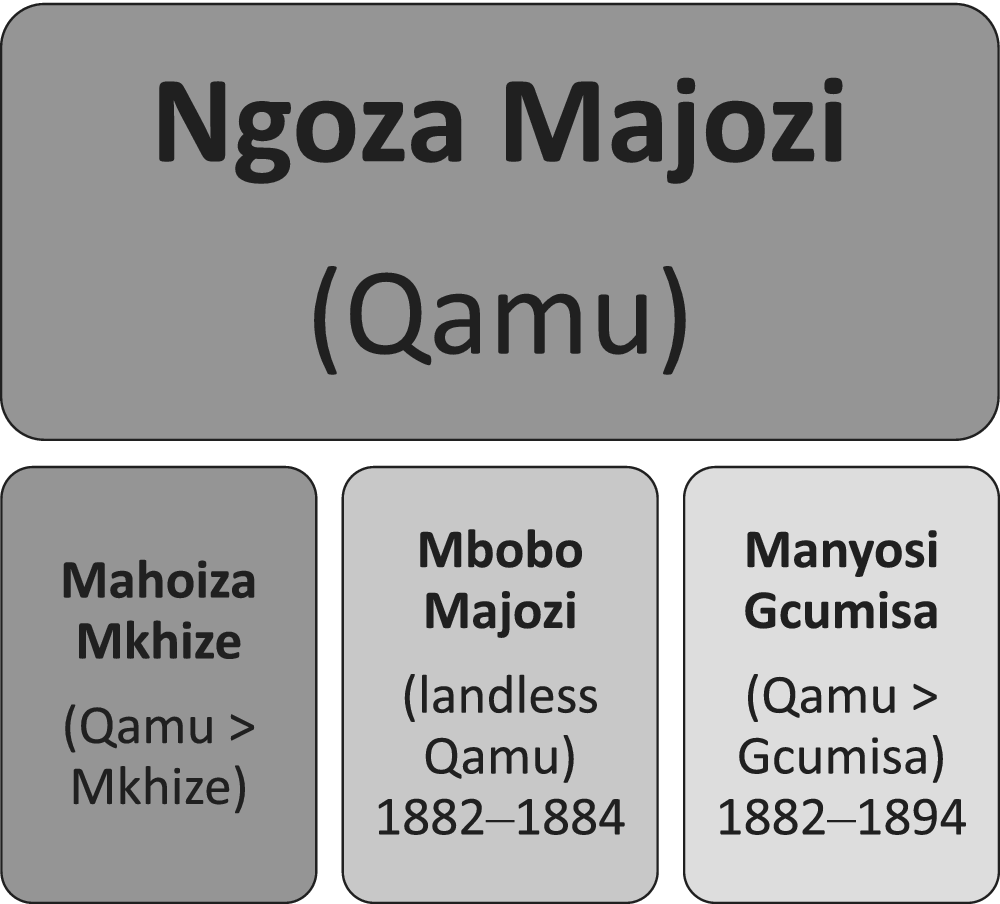

Ngoza and Mahoiza’s claims to power were based on the consent of the people. There were no boundaries around their chiefdoms and no land connected to their authority. But in 1882, when colonial officials divided Mahoiza’s Qamu chiefdom around these factions, they began to define chiefly authority in relation to land. Magistrate H. C. Campbell restricted Mahoiza’s jurisdiction to homesteads on private lands; his chiefdom would later take his surname, Mkhize, as its name and end up landless because of its position on private lands. Campbell divided the remainder of Mahoiza’s chiefdom between those favored by his former subjects—Manyosi and Mbobo. Manyosi was elevated to chief of homesteads on location and private lands. His portion of the Qamu would take Manyosi’s name, Gcumisa, as its name and remain landed, based on the location. Later Qamu chiefs would consider this as theft of location land. Mbobo became chief of homes on the location but without boundaries (SNA1/1/54, 1882/272, Pietermaritzburg Archival Repository--PAR; SNA1/1/112, 1889/68; SNA1/1/298, 3846/1902). In essence, colonial officials made Mbobo and Mahoiza landless chiefs in the midst of their efforts to tie chiefs to land. (See Figure 2)

Figure 2. Division of Ngoza’s Chiefdom

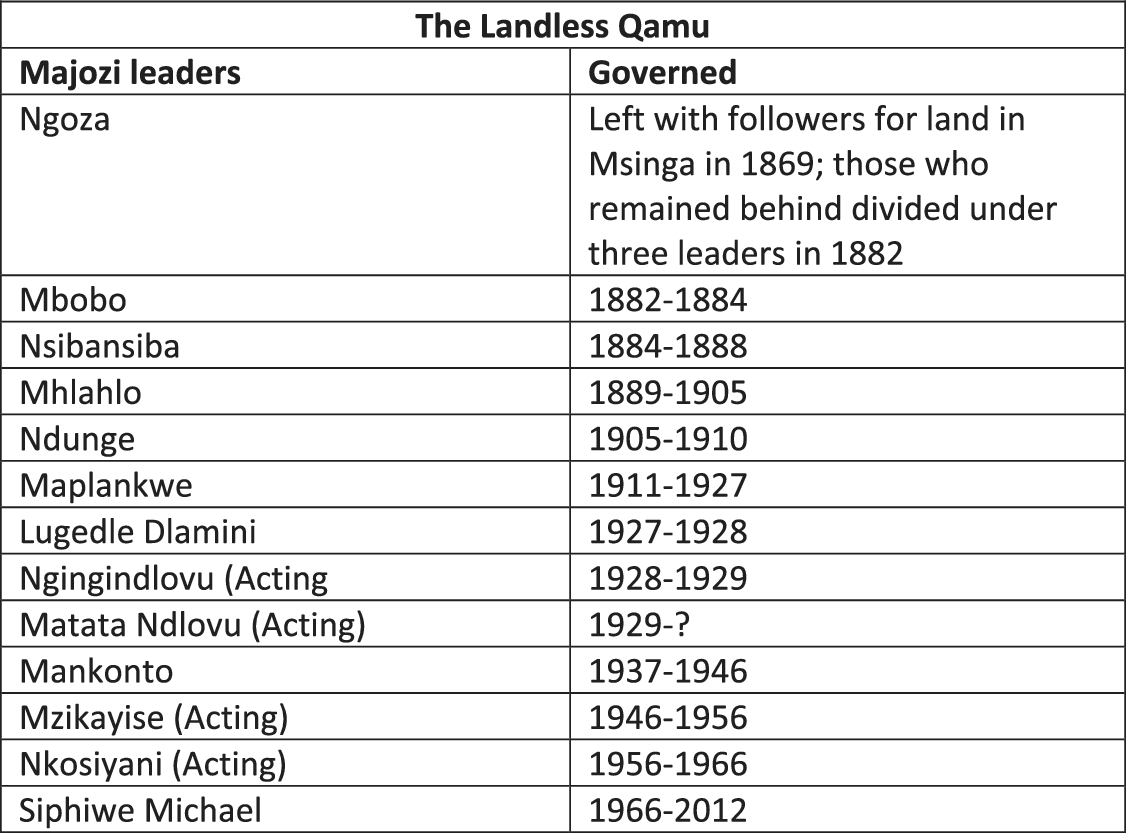

The location of Majozi subjects across magisterial districts was something that needed to be fixed in the eyes of white officials. Throughout the early 1900s, Mbobo, his brother Nsibansiba, and acting chief Mhlahlo governed their subjects under pressure from the colonial government to transfer their allegiance to landed chiefdoms or other chiefs who resided in the same district as they did. (See Figure 3 for a list of Qamu leaders.)

Figure 3. Majozi Leaders

Beyond this precarity born out of landlessness, the Qamu suffered from a series of sick heirs, less than attentive regents, and disputes between the sons of Mfulatelwa. Mhlahlo governed until his death in 1905, but his authority did not go unchallenged. On account of divisions within the Qamu, colonial officials ordered Maplankwe kaMfulatelwa to remove his homestead to protect the young heir and acting chief (SNA1/1/142, 1891/738). Maplankwe settled in KwaXimba but was aware that men who had served the British as he did—such as his uncle Ngoza—had been made chiefs. Maplankwe was relentless in asking to be raised up (SNA1/1/313, 1926/1904; SNA1/1/349, 1906/2846). He finally achieved this after the death of the Qamu heir (SNA1/1/464, 1770/1910). In 1911, Maplankwe became chief of the Majozi, with authority over followers of Mhlahlo as well as over subjects formerly under the Mkhize on private land in the Camperdown District. These latter individuals had been forcefully transferred to Maplankwe’s jurisdiction to reduce the pledging of allegiance across district boundaries (1/CPD3/2/2/5, PAR). Maplankwe became chief over subjects living almost entirely on private land; there were still no boundaries or defined territory for the Qamu.

The combination of pressure from neighboring chiefs and white officials, overcrowded location land, and the vulnerabilities of tenancy on private land meant that Qamu subjects, still claiming ties of allegiance to landless Majozi chiefs, lived spread across white-owned farms. In the first half of the twentieth century, Majozi leaders and Qamu subjects moved frequently in the wake of evictions that were related to the shift from rent to labor tenancy as well as white agricultural land use. During this time, the Majozi leaders did occupy a number of the farms that were claimed after apartheid, particularly those owned by the descendants of the early British settlers W.F. Ellis and Harriett Pope. In 1870, the couple purchased Sub 10 of Ockert’s Kraal, Vaalkop/Dadelfontein, and Spitzkop/Zandfontein. Their sons, J.A. Pope-Ellis and L.E. Pope-Ellis, as well as J.A.’s son F.C. Pope-Ellis, all leased parcels of their inherited land to African tenants.

African rent tenants were critical to the economic sustainability of the region, even though such tenancy was limited by the 1913 Land Act. Many local rent tenants had been in place since before the act and continued to pay rent to settler landlords through exemption, while others received new ministerial permission or paid rent without the approval of the administration. Rent tenancy was distinct from labor tenancy, in which a homestead provided labor for six months of the year in return for permission to use the land, and was preferred due to the greater degree of autonomy it afforded. Before the viability of white commercial agriculture in the 1880s, the colonial state, settlers, and land speculators all collected rent from these so-called squatters. The 1913 Act converted many Africans outside of the locations to labor tenancy, but it did not completely end the practice of rent tenancy during the interwar years (McClendon Reference McClendon2002:48–53). In 1933, the Natal Chief Native Commissioner estimated that there were some 200,000 to 300,000 rent-paying tenants or other non-labor tenants in the province (McClendon Reference McClendon2002:94).

L.E. Pope-Ellis applied, in 1929, to have his portions of the Spitzkop/Zandfontein, Vaalkop/Dadelfontein and Lange Hoop farms adjoining the location added to the list of land to be released under a proposed land act (1/CPD3/1/1/1/, 2/3/51). While the late 1920s saw a boom in the Natal Midlands’ exports in wattle and wool, elsewhere in South Africa agricultural prices struggled in the Great Depression through World War II (McClendon Reference McClendon2002:20). A number of other farmers in the region would follow a similar course in the early 1930s (1/CPD,3/2/1/2, 2/3/91).Footnote 7 Pope-Ellis sought permission to take on additional rent-payers. Without new paying residents, he argued, he would need to evict the others and sell the farm (1/CPD3/2/1/1/2/3/51). However, Pope-Ellis’ properties were not accepted into the list of scheduled farms.

The Majozi chiefs attempted to address this land insecurity. In 1913, Maplankwe appeared before the commissioner to complain about the trouble his people experienced when they were ejected from private farms. He asked for location land under his jurisdiction to house them. The commissioner advised him to be patient while the government considered additional land purchases for Africans (1/PMB3/1/1/1/2, MC372/13, PAR). In 1916, John Pope-Ellis evicted Maplankwe’s own homestead. Maplankwe again asked for location land, a nearby farm, or Crown lands near Msinga. Maplankwe’s situation was not unique. The Natal Chief Native Commissioner reported in 1916 that chiefs could be found in almost every district in Natal with chiefdoms on private lands (1/PMB3/1/1/1/2, MCC122/14). Maplankwe moved to J.S. Scheepers’ portion of Lange Hoop farm, only to be evicted again two years later (1/PMB3/1/1/1/2, MCC122/14; CNC324, 1918/1572). He and a number of other Majozi returned to the Pope-Ellis property as tenants.

The landless Qamu chiefs sought to benefit from the passage of the 1936 Act, which promised funds to purchase farms to supplement the locations. When Mankonto became chief of the Qamu in 1937, officials restricted his authority to the Pietermaritzburg and Camperdown districts (1/CPD3/2/1/1/2/3/51). In 1938, Robert Mattison purchased Pope-Ellis’ Dadelfontein and gave notice to the chief to vacate; Mankonto and twenty other homesteads remained in place until 1940 due to an outbreak of East Coast Fever. Most of the homesteads owned stock and did not want to limit those or render labor (1/CPD3/2/2/5, N1/1/3(9)). Mankonto initially requested to return to location land at New Hanover, which he saw as the “great place” of his chiefdom. Then he asked to live on Pope-Ellis’ Spitzkop/Zandfontein, which the Trust was considering purchasing. In yet another request, he claimed to have one hundred families willing to pay rent (2/PMB3/1/1/2/31, 2/28/2, PAR). Several local magistrates empathized with the Qamu’s landlessness and recommended that the Trust purchase farms under the 1936 Act. But this process was slow and inefficient (Feinberg Reference Feinberg2015).

Mankonto left these meetings with the belief that the government had agreed to purchase land for the Qamu; this conviction persisted among his successors, including Siphiwe. Mankonto died in 1946, still living on Pope-Ellis’ Spitzkop/Zandfontein. Successive regents made pleas calling on this promise. In each case, officials declared that no pledge had ever been made. Acting Chief Mzikayise began to collect funds to purchase a farm for the Qamu, but the scheme failed. In 1951, he moved to another of Pope-Ellis’ farms (1/CPD3/2/2/5, N1/1/3(9)).

Tribalization and spatial segregation intensified under apartheid, and the Majozi leaders experienced this acutely. Between 1955 and 1958, commissioners prepared the chiefdom for the establishment of a Tribal Authority under the 1951 Bantu Authorities Act, which was designed to give effect to separate development. In 1955, 502 Qamu homesteads were located scattered across ten white- and trust-owned farms as well as on locations and mission reserves under the authority of other leaders. The largest concentration remained on Spitzkop/Zandfontein, under eighteen different owners. The commissioner planned to finally territorially define the Qamu and recommended the jurisdiction include Spitzkop/Zandfontein, Lange Hoop, Ockert’s Kraal, New England, and a portion of Goedverwachting Trust Farm. Doing this would “assist the migratory Qamu tribe with some ground” until the Trust could secure land for them. Like his predecessors, the commissioner recommended the Trust purchase Spitzkop/Zandfontein, as it had become a “veritable Native Location.” But the government was not willing to act on this suggestion, and refused to establish a Tribal Authority on private land (NTS8991 211/362(10), NAR).

In the midst of these considerations, in March 1956 the Natal Urban Areas Commissioner arrived at Spitzkop/Zandfontein to give notice to the rent tenants to vacate. Section 15 of the Natives (Urban) Areas Act of 1945 did not allow for rent-paying tenants on farms within five miles of town lands. Additionally, a 1956 Amendment to the Land Act tightened control on tenants, prohibiting farmers from keeping rent tenants after August 31, 1956 (Surplus People’s Project 4:45). On F.C. Pope-Ellis’ land, there were fifty-seven families, comprising an estimated five hundred persons with five hundred head of cattle. Some of the families had been there for over eighty years, predating the Union and the arrival of the railway in 1880. It was also home to Chief Manzolwandle Mlaba, who had moved there to escape succession disputes.Footnote 8 On Subdivisions 5, 6, and 7, forty families lived—including acting chief Mzikayise Majozi—with two hundred head of cattle. These latter subdivisions are those on which Siphiwe would grant sites after 2010.

The regent Mzikayise and Pope-Ellis sought to secure exemptions from the Group Areas Board, which centralized control over resettlement under the Group Areas Act of 1950. Mzikayise asked to raise funds to purchase the land. He knew full well they would be expected to become farm laborers following this eviction: “If there is room on other farms, it would be of no use to the tenants of this farm. They have never worked as labor tenants and they cannot do so.” Due to the fact that there were landowners looking for farm laborers, the requested exemption was refused (1/CPD3/2/3/2/5, N2/9/6/1). At this point, Mzikayise asked to be relieved of his regency and sought out land for himself (NTS8991, 211/362(10), NAR).

The new regent, Nkosiyani, was told to settle at Trust Farm R6 in the Camperdown District, on a temporary basis, but he could only take five families with him. R6 had no arable land and was promised to be added to the Makhanya territory. According to Thulani Mlambo, whose family was evicted prior to his birth, “the whites dumped them in Georgedale,” unless one knew someone with whom they could find access to other land.Footnote 9 Nearby Georgedale began as a freehold area of Christian converts, but by the 1950s it included other black land owners as well as rent-paying tenants, who began to hire land due to the increasing restrictions on rent tenancy on white farms (Bonnin Reference Bonnin2007:chapter 3).

By 1966, when Siphiwe was installed over the Qamu but only in the Camperdown District (authorities had finally succeeded in restricting the chiefdom to one district), officials agreed to allow the farm R6 to be occupied by only the Qamu. A Tribal Authority could now be established (COGTA147, (4)N1/1/12). The records do not suggest why, but Siphiwe refused to live at R6. He stayed in Imbali until he ceased working and lost privileges to live in the urban area. Authorities gave him permission to occupy a temporary dwelling in the New Town camp (1/CPD3/2/3/2/1, N1/3/2, PAR).

Since there was no land for the chiefdom, in 1968 the Camperdown Bantu Affairs Commissioner informed Siphiwe that the chiefdom would be dissolved. Siphiwe turned to the Zulu monarch, who appealed on his behalf. The state backtracked on the dissolution of the chiefdom, but nothing was done about its landless status (DDA 374(36)N1/1/3/4, PAR).

Siphiwe couched his requests for land in the language of the historical promise to his predecessors. He pleaded with both officials of the KwaZulu Bantustan and the South African government. Speaking in 1974, Siphiwe said that the authorities had told Mankonto after the war that “he would be bought another farm where he could settle with his followers.” They hoped this would be Spitzkop/Zandfontein, onto which Mankonto moved in 1940 (Majozi). The issue came to a head again between 1976 and 1979 (1/CPD3/2/3/2/1, N1/1/3, PAR). T.C. van Rooyen, who was with the CNC’s office at the time of Siphiwe’s move to New Town, remembered that he could find no evidence the Majozi had been promised land and stressed that Siphiwe had been granted space for a personal home, not for a chiefdom. In 1980, the Commission for Cooperation and Development considered purchasing portions 17 and 19 of Spitzkop/Zandfontein for the Qamu as part of the consolidation of KwaZulu (DDA87(5)N2/7/2, PAR). As late as 1980, Siphiwe still had several followers on R6, but most continued to live on white-owned farms (1/CPD3/2/3/2/1, N1/3/2, PAR). He continued to inquire after land into the 1980s (DCD2952, 25/1/24/2/26, NAR). As of 2011, the Final Report of the government-sponsored KwaZulu-Natal History of Traditional Leadership Project listed Siphiwe as a recognized traditional leader (Houston & Mbele Reference Houston and Mbele2011:27–28).

Making a Landless Chief Landed

Until his death in 2012, Siphiwe advanced arguments that his family and chiefdom had occupied the farms at Mpushini since the 1800s. He situated this occupancy as evidence of a long history of Majozi chiefs holding the land in question before their dispossession. Siphiwe’s 1996 historical recounting does not acknowledge a history of service to colonial leaders, as his ancestors did. But it does highlight that the Majozi chiefs had long sought land. The records show how they continuously deployed history—first of services to and then promises from white authorities—across the twentieth century to claim land that would territorialize their authority. In the twenty-first century, Siphiwe successfully claimed portions of Spitzkop/Zandfontein by eliding the removal of his family’s homestead with that of a chiefdom. This complicated history of the making of a landless colonial chieftaincy, the growing constraints on people’s ability to access land of their choice, and overlapping rights to the land did not feature in RLCC plans to acquire the Mpushini land.

Nine claimants—including four Mchunu individuals, Thembinkosi Mncwabe, Siphiwe Majozi, and three others—submitted claims for the Mpushini-Lion Park farms in 1998. What happened next is less clear. The KZNRLCC offices faced tremendous challenges—of understaffing, sunset clauses that kept apartheid officials in place, and weak information management. The latter particularly impacted the overlapping and competing claims. Between 1995 and 2000, KwaZulu-Natal alone had nearly 15,000 claims, of which only 1,064 had been gazetted for investigation and only thirteen of them settled (Walker Reference Walker2008:15, Reference Walker2012). The KZNRLCC met with representatives of the claimants—identified ambiguously in KZNRLCC records as AmaQamu, Mkhondeni/Ashburton, and Mncwabe—in 2001 to discuss a possible amalgamation of their claims. Deborah James’ work shows this to be a strategy accepted by both the commission as well as the claimants to speed the settling of claims (Reference James2007:chapter 2). Appearing for the “AmaQamu” were Hlengiwe Majozi and Mr. Mlambo (presumably Royal Mlambo, as both would become trustees with Siphiwe). The Mkhondeni and Mncwabe representatives refused to be amalgamated; they would not recognize Majozi as chief (KZNRLCC Mpushini Meeting: July 15, 2001, LRP).Footnote 10 The Mchunu factions were not represented at this meeting, but their claims were amalgamated with the others.Footnote 11 Bhekizazi Phoswa, an attorney later involved on behalf of Mchunu, believes that officials saw Majozi’s claim for all of the land and assumed that the other claims were part of his request to restore a chiefdom’s land.Footnote 12

The Section 42D KZNRLCC memorandum that outlines the Mpushini land acquisition positions Majozi chiefs as historical leaders in the region in a manner incongruous with historical record. After describing the tenants’ historical dispossession of land, the memo explains, “At the time of removal Inkosi Mankonto Majozi was the chief.” It uses the elision that Siphiwe Majozi regularly deployed: “Originally the farms under claim were under the tribal jurisdiction of Amaqamu before it was subdivided and given to white farmers” (Commission on Restitution of Land Rights, Memorandum, KRN6/6/6/E/38/0/0/68). When the government gazetted the two claims on a total of 110 properties (sub-divisions of several farms, including Spitzkop/Zandfontein and Vaalkop/Dadelfontein, among others) for investigation, they listed the claimants as “M.S. Majozi on behalf of the Amaqamu tribe” (Notice no. 1701 of 2002 and 1773 of 2003).

As the KZNRLCC faced the initial ten-year deadline for land restitution, they adopted a strategy to fast-track research on unverified claims (Commission on the Resititution of Land Rights 2007). Between 2007 and 2010, the state spent R25 million to purchase twelve farms through the willing-seller/willing-buyer process (Noseweek 2016). Some of these were part of claim KRN6/2/2/E/4/0/0/9 and others KRN6/6/6/E/38/0/0/68. Landowners contested the claims on the other farms.

Inkosi Majozi set up a trust in the name of his chiefdom, following the terms of the Trust Property Control Act of 1988 under the Master of the High Court in 2007, to administer the awarded land. In choosing a trust rather than a communal property association (CPA), Majozi likely was following advice from those with more knowledge or expertise. In many claims, land brokers have emerged to bridge the gap between complicated policy and the claimants (James Reference James2007). Traditional leaders, like Majozi, worked—with and without success—to be included in CPAs (Beinart, Delius, & Hay Reference Beinart, Delius and Hay2017:chapter 8). CPAs have not been without problems, but they offer more oversight mechanisms than trusts. From 2009, the Department of Rural Development and Land Reform (DRDLR) began to pressure officials to favor trusts over CPAs in cases where traditional leaders were involved. Sithe Gumbi, scholar and former Registrar of CPAs, believes that trusts allow for abuses of power (Weinberg Reference Weinberg, Beinart, Kingwill and Capps2021:218). This was part of a larger trend that was documented for the first decade of the twenty-first century, where broader political developments contributed to an environment more conducive to prioritizing chiefly claims (Claassens Reference Claassens2014; Zenker Reference Zenker, Zenker and Hoehne2018a). Mlambo found it incredulous: “So now, we came as if the claim was for his chieftaincy and the land was brought back to him… he held the information.”Footnote 13

Mlambo’s contention that Majozi “held the information” signals how many of the original claimants knew nothing about the establishment or operation of the trust. The trust deed names Majozi as founder and trustee, by virtue of his status as inkosi, and among the trustees, Cyril Bafana Shabalala (Deed of Trust). Shabalala’s connection to the Majozi faction remains unclear, but he succeeded Majozi as chair of trust. Much of the land restored or redistributed in South Africa since the advent of land reform is held by CPAs or trusts such as this. Family rights within CPAs and other forms of communal tenure remain without national policy to guarantee them (Beinart, Delius, & Hay Reference Beinart, Delius and Hay2017:chapter 8).

On the strength of his authority as trustee, Majozi began to allocate residential sites on the awarded land on Lion Park Road, “selling” plots for R10,000 to R50,000 via word of mouth and the website Gumtree (Noseweek 2016 ). Despite developmental, environmental, and other authorizations that apply to the restituted farms to address the legacies of apartheid and ensure ecological considerations, homes proliferated without municipal approval. (Photographic Report of Illegal Homes, provided by Mchunu). Those who paid received no title deeds or permissions to occupy.Footnote 14 The majority of South Africans hold land or dwellings outside of the titled property system in this way (Hornby et al. Reference Hornby, Kingwell, Royston and Cousins2017:7–8).

Majozi admitted to the press that he sold land access, “saying that as an inkosi he cannot live in the vast area alone, and the buyers needed plots” (Magubane Reference Magubane2011). One man purchased a plot, never occupied it, and was refused a refund of the deposit he made into the “Amaqamu traditional authority” account. The Mchunu faction and a number of landholders suspect that a land claim official working with Majozi also benefited from the sales (Noseweek 2016). The Mchunu secured the assistance of the Association for Rural Advancement’s (AFRA) Land Rights Legal Unit. They sought a court interdict to reverse the award to Majozi and to stop the sale of residential plots in 2011 (LCC109/11, November 22, 2011). Only with this legal challenge did they realize that their claims had been amalgamated with Majozi’s (Noseweek 2016).

Firstcomers Accounts and the History of KwaZulu-Natal

While the Mchunu waited for the case to go to the Land Claims Court to reverse the DRDLR’s awarding of the land to Majozi, they began to document their own past. Armed with an awareness that the courts consider grave sites and oral history as evidence, they recorded interviews with members of the community who shared histories that connected those associated with the Mchunu faction to the land before the arrival of Majozi or white settlers. They recognize Majozi’s family history with the land but stress that this history is not one of chiefly authority on the farms. The Mchunu’s firstcomer narratives reflect the precolonial and colonial history of Natal. Several elders recounted the history of the region using cannibal tales and the rise of King Shaka Zulu to connect themselves to the land at Mpushini.

These claimants/beneficiaries use oral accounts to position themselves as firstcomers. The archival evidence that cites families on some of the farms in question prior to the arrival of the railroad suggests the possible legitimacy of such claims. These recently recorded oral accounts, like many others of the KwaZulu-Natal region, are marked by the rise of Zulu nationalism, in that they center on the first king of the Zulu in ways not always historically corroborated.Footnote 15 King Shaka built a kingdom through a combination of diplomacy, skill, and force, incorporating discrete polities hierarchically. Thulani Mlambo referred to this historical state-building when describing his ancestors:

My grandfather was a Mlambo, they were great-great giants of the mfecane tribes [those chiefdoms who were involved in or experienced state expansion in southeast Africa]. There was no one above to control them because they were one of those warriors, the powerful people you know. Therefore, they were not interested in this thing of confining settlement, confining people under certain leadership.Footnote 16

One grandmother also dated these families to the time of the Zulu expansion. She explicitly used an oral land registry to tie her family and those of the claim to the land in a story about the movement of Shaka’s armies through the region. She explained how well-known mountains in the region were named for warriors who were buried in their shadows. Those who stayed behind to bury Shaka’s soldiers become the founding fathers of families such as the Mchunu, who are remembered by gravesites on the claimed land.Footnote 17 These “ideologies of attachment” reveal how claimants feel connected to not only the land but also each other, living and dead (Shipton Reference Shipton2009).

In the process of state-building, those of royal descent reserved the name “Zulu” for themselves and encouraged integration of a second tier of those who were genealogically related (both real and fictive), while labeling those on the geographical margins as menials. Mpushini sat on the periphery of the kingdom’s power, and oral histories of the region attest to the distance from the security of the monarch with accounts of amazimu, or so-called cannibals. Stories of “cannibalism” represent social disruption, famine, and banditry during the consolidation of the kingdom (Hamilton Reference Hamilton1998). The elders interviewed described those warriors who remained behind as choosing the sites at Mpushini after escaping amazimu. “Amazimu followed them, but then they moved up the hills. They moved away until they reached this area.”Footnote 18

These accounts also recognize colonial transformations to local governance and the chieftaincy as they recall the introduction of appointed chiefs. The Mchunu faction of the trust acknowledges that Mankonto and his family moved onto farms in the region, but they argue it was a region without chiefs. Similar to Mlambo’s claim that “there was no one above to control them,” one grandmother insisted that only after the region became the Colony of Natal—when the colonially-appointed chief Mdepa Mlaba arrived—did the people of the region recognize any chief, and then it was through the local headman.Footnote 19 Musa Mchunu directly connected this to colonial policy. The only reason his ancestors came to recognize Mdepa was because “if you are a black person you must fall under the chief because if you have to pay these fees [taxes] you have to, you cannot be someone who does not belong anywhere.”Footnote 20

To seal their status as firstcomers, the grandmother contends it was one of the original families, the Mlambos, that helped Mankonto Majozi identify land on which to live.Footnote 21 Records do put Kwela Mlambo, father of Royal Mlambo (of Siphiwe’s trust), together with Mankonto and his brother Richard on Spitzkop/Dadelftontein in 1934 as tenants of L.E. Pope-Ellis (1/CPD3/2/1/1/2/3/51). Another elder recalled that when Mankonto and his wives arrived in the region among Mlambos and Mthembus, there were no chiefs, only headmen:

Majozi found people staying here. He was from KwaSwayimane and he moved here during the war… Then Majozi built his house next to Mthembu’s clan. Mpisi Majozi also had a house next to the road, the very same road where there were Mlambo people. But then I am not sure how he obtained the chieftainship. At the time there were no chiefs, only headmen.Footnote 22

While Mankonto arrived as a chief, recognized by the government as a chief of the Qamu, not all of those in the region into which he moved considered him their chief, and he was not a chief by virtue of land.

This positioning of themselves as firstcomers proved to be unnecessary to the control of the trust and the remaining land claims. The Mchunu faced significant challenges that brought them into an alliance with the owners of the remaining farms that were under claim. With AFRA’s strained budget and large caseload, the faction’s lack of funds for legal support, and Siphiwe’s death, they strategized. While some of the farm owners wanted to protest the claims as invalid, others began to consider a settlement as long as the Mchunu faction would prevail and work to preserve the land.Footnote 23 AFRA’s Michael Cowling explained of the alliance, “That was very weird because you didn’t know whose side you were on, but we find ourselves working very closely with the attorneys and legal representatives of the white farmers. Because they were challenging Majozi’s authority, just as we were…”Footnote 24

On the previously-awarded land, the Mchunu decided that they would try to take control of the Trust, now with Shabalala as Trustee and chair, according to the terms of the trust’s constitution. AFRA could find no evidence that the board complied with the constitution, which required them to meet once every quarter, hold an annual general meeting, and maintain records. The term of office of the board had expired, so across meetings with the RLCC in 2013–2014 they convinced the trustees to establish an interim committee in order to enable an election. At a 2013 meeting, they agreed to work together to remove the illegal occupants from the land, to update the list of beneficiaries to reflect those sidelined from the trust, and to facilitate a general meeting to elect a new board (Settlement Agreement Case LCC109/2011-Final). By then, R27 million granted to provide production capacity to the farms had disappeared (Noseweek 2016).

Both factions held an election. Shabalala held one in October 2014, without informing Musa Mchunu and most of his supporters, to which they invited the alleged beneficiaries who did not appear on the original list—an increased one thousand beneficiaries. The Mchunu faction also held a meeting, without being aware of the first meeting but informing Shabalala, in December 2014. Those in attendance (180 beneficiaries, but none of the original trustees) elected Musa Mchunu as the new chair (Interim Committee Electoral Report, February 12, 2014, CR; 2015 AEMCT Annual Report). Both factions submitted their material to the Master of the High Court to obtain Letters of Authority that would enable them to act. The Mchunu suspected foul play when the court issued Letters to Shabalala in 2015.Footnote 25 They took the matter to the High Court (Declaration, J.M. Mchunu and others versus Master of the High Court, Pietermaritzburg and others, April 28, 2016).

The battle over control of the trust delayed the court date on the remaining land under claim.Footnote 26 The judge thus ordered an election of a Section 10(4) committee with five representatives from each faction to represent the community in court. While the claimants did elect the committee, Shabalala refused to cooperate (2015 AEMCT Annual Report). In 2017, Shabalala applied for an order to remove the Mchunu group from the 10(4) committee, but the judge found that the committee should continue to represent the community in court (LCC 01/2009B, Azibuye Emasisweni MaQamu Trust and Minister of Rural Development and Land Reform and other respondents, Durban, October 4, 2017).

The alliance between the Mchunu faction and the landholders continued. Those within the alliance shared an opposition to Majozi/Shabalala and a commitment to environmentally sustainable development. In July 2018, Shabalala started clearing land that had been awarded to the Trust in the Lower Mpushini Valley, an action that constituted illegal development. The Mchunu beneficiaries joined with environmentally conscious landholders to prevent the ongoing attempts at land clearing. The organized protest was met by heavily armed guards who refused them access (Pieterse Reference Pieterse2018a, Reference Pieterse2018b). The next month, the Mchunu faction marched to the High Court to demand an investigation and a withdrawal of the Letters of Authority from Shabalala (Pieterse Reference Pieterse2018c).

The Majozi/Shabalala faction benefitted financially from selling land access until early 2020, when the Mchunu group finally prevailed. In 2019, the RLCC insisted on a homestead verification in which the trust beneficiaries had to physically point out where their ancestors had lived. Shabalala could not, and the owners of 260 verified homesteads requested a new election. Shabalala resigned from the board, and in 2020 the Master of the High Court awarded Letters of Authority to Musa Mchunu and ten others (C.B. Shabalala to Trustees, December 11, 2019; Letters of Authority, January 2020). The new trustees now control a trust, named after a chiefdom, with land degraded by a decade of unplanned residential growth and several properties damaged by nearly two decades of neglect. The Mchunu family works to gain control of the trust account as they wait for the RLCC to settle with the remaining landholders out of court.Footnote 27

Conclusion

The land restitution case at Mpushini exemplifies some of the trends in land reform scholarship—particularly that which documents benefits to traditional authority. But this case also reveals how KwaZulu-Natal’s contested past came to be used to position a historically landless and colonially-created chiefdom as dispossessed of land it never had and to position others as firstcomers tied to land through their experience of the growth of the Zulu kingdom.

The landless Inkosi Siphiwe Majozi successfully manipulated a land claim to benefit himself as a landed chief, from which he and partners such as Shabalala profited. In his historical recounting, Siphiwe merges his family rights to land with that of a chiefdom’s territory. Majozi’s ancestors had fled to Natal in the colony’s earliest days and found themselves continuously in search of land for their colonially-created chiefdom. Majozi may have a right to Spitzkop/Dadelfontein, even as a latecomer, but not as chief of that territory. The Mchunu, Mlambo, Mthembu, and other families argue their historical precedent in the region by deploying “firstcomer stories” of cannibals and King Shaka, particular to the history of KwaZulu-Natal, to validate their rights to the land and to undermine Majozi’s control.

These overlapping and competing claims to land make adjudicating land reform cases incredibly difficult. If the post-apartheid government intends to promote chiefly authority as tied to the land, the Qamu—whoever that may be who continue to recognize the Majozis as chiefs—may even be entitled to land. But records make clear that the Lower Mpushini-Lion Park farms in question were never home to the Qamu chiefdom as a chiefdom, and that people living on the land paid allegiance to not only the Qamu chief but to other leaders as well. And yet Inkosi Siphiwe used South Africa’s land reform agenda to make a landless chief landed.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Muziwandile Hadebe, Lauren Jarvis, Liz Timbs, and Tara Weinberg, as well as anonymous reviewers, for feedback. Special thanks to Musa Mchunu, Mehluli Mchunu, Thulani Mlambo, Pandora Long, Nick and Nicole May, Michael Cowling, and Bhekizazi Phoswa for sharing their documents and experiences with me.