Context and dietrologia

Critique is the most legitimate deployment of knowledge. (Arowosegbe Reference Arowosegbe2010)

I am grateful to all the authors who contributed thoughtful reflections on my 2016 and 2023 articles; and to the editors of Africa for calling on me to have the last word and write back in a compelling conversation on knowledge production and the crisis of public universities in Africa. It is time to pull the strings together. As I seek to do this, my aim is less to answer – collectively or individually – the authors and their contributions to my articles. Rather, I endeavour to put on record further thoughts on issues about which I have been silent in earlier publications. In pursuit of a longstanding interest in (1) how knowledge is produced on non-metropolitan societies, (2) the future directions of postcolonial universities, and (3) the relations of knowledge and power in Africa, I ask further questions and examine new archives and bodies of evidence. I appreciate the difficulty of ignoring the economic determinants of Africa’s material base – built as it is on dependent and disarticulated capitalist economies. In recounting my lived experience as an eyewitness to university life in Africa, and in shedding more light on the historical problems that I grapple with, I acknowledge change and continuity in historical explanations and the historiographies of my universe. In the present as in the past, the sense of sight shapes experience. I admit, with Ludmilla Jordanova (Reference Jordanova2012: 3), that vision has a history and that objects necessarily play a central role within it.Footnote 1 As Peter Burke (Reference Burke2008) has shown, looking at alternative evidence and records enables one to examine historical problems and subjects in a different and hopefully renewed way. Historians therefore ask different and new questions. Such questions are informed by the changing nature of the environments and universes of analysis, historiography and historical scholarship. These activities demand continuous examination of existing arguments and conclusions against the backdrop of changing evidence and facts. Understood as the best intellectual imagery of modern society, I turn to the postcolonial universities in Africa. Ultimately, this effort, together with my other works, should illuminate what one might safely conjecture about the future of the universities in Africa.

Introduction

Attacks on academic freedom and higher education are globally acknowledged. These undermine the safety and well-being of academics, public intellectuals, students and the universities. The trial of Socrates (470–399 BC) by the state in Ancient Greece is one of the oldest accounts of such attacks. From this period onward, the relationship between the intellectual and the state has provoked a huge genealogy of discourse.Footnote 2 Intellectual–state relations have remained controversial and tense (Wagner Reference Wagner2023). The resultant tussles have extended beyond the Renaissance to the development of higher education and the university as a specialized unit of the modern state. This was affirmed by Wilhelm von Humboldt’s (1810) concept of the university (Remy Reference Remy2002).Footnote 3 Modern understandings of academic freedom have, from then, crystallized across the institutional sites of the university (Marini and Oleksiyenko Reference Marini and Oleksiyenko2022). Here, modernity was marked by the birth of institutionalized systems of thought; the disappearance of the Renaissance intellectuals; and the professionalization of disciplinarily trained academics–intellectuals–scholars.

The importance of academic freedom and the debates on it cannot be overemphasized. Its dynamics are underlined by changing contexts across space and time. In Europe and North America, this dates back to the entrenchment of social inequalities in the universities before and during the twentieth century. For example, in its 300-year history (1724–2024), the Regius Professorship of Modern History at the University of Cambridge, appointed by the Crown on the advice of the prime minister, has remained an exclusive male-dominated position.Footnote 4 Historical collections in the special sections of the library of the University of Cambridge have documented the long and violent work on women’s exclusion in universities in the UK. Different accounts and dates exist for the granting of admission, graduation and membership rights to women in British universities.Footnote 5 Women struggled to navigate male-dominated workplaces. As historical actors and as interpreters of the past, their roles outside establishment knowledge-creating institutions – libraries, museums and universities – were largely marginalized. The male domination of the production of historical knowledge and the unsurprising fact of misogyny in male-only British academic institutions have been examined by Kate Dossett (Reference Dossett2024).

During the 1930s and 1940s, the entire academic system in the USA was purged of its Jewish professors. For a long period, Black students could not attend many universities in the USA and many had no Black faculties. When these were eventually allowed, they were actively separated from their white counterparts. From its early colonial history to the Great Depression and the 1930s, different contexts and statistics illustrate the exclusion of women and overrepresentation of men in American higher education. With different dates and details in terms of admission, attendance, graduation and membership rights, all the Ivy League universities had quotas for Black, Catholic and Jewish professors and students. Barring Cornell, PennsylvaniaFootnote 6 and Radcliffe, these universities did not admit female students until the late 1970s.Footnote 7 Their definitions of the best, brightest and productive students excluded women. Female students were first admitted to higher education in 1837 at Oberlin College. This was more than 200 years after Harvard College was established for men. It was not until the 1980s that the Ivy League universities began graduating female students. In 1902, Radcliffe College, a women’s liberal arts college in Cambridge, Massachusetts, awarded its first doctorate degrees. Harvard Graduate School of Education admitted its first female students in 1920. Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences admitted its first female students in 1963. It awarded degrees to Radcliffe students in 1963. This continued into its merger with Radcliffe in 1977. Princeton and Yale admitted women in 1969, Browne University 1971, Dartmouth 1972, and Columbia University 1983 (Graham Reference Graham1978; Evans Reference Evans1992; Eisenmann Reference Eisenmann1997; Eisenmann et al. Reference Eisenmann, Hutcheson and Nidiffer1999).Footnote 8 Many of the theoreticians of intellectual production in the USA – Theodor W. Adorno and Hannah Arendt, for example – responded to some of these burning contexts. Later, Edward W. Said and Joan W. Scott wrote about certain topics that were, and still are, taboo in the American academe. In South Africa, the genealogy of similar contexts dates back to the 1930s and 1940s, an era in which the National Party’s government (1914–97) institutionalized apartheid segregation through official legislation and extended it to all places of learning. In the universities, this culminated in the Extension of University Education Act of 1959. This Act made it a crime for non-white students to register at the formerly white South African universities without the written approval of the Minister of Internal Affairs. This law evicted Black South African students from those universities for about thirty years. The role of Thomas Benjamin Davie, vice chancellor of the University of Cape Town (1948–55), in defence of academic freedom has been noteworthy.

Today, beyond the questions of what can be researched and taught vis-à-vis who can be offered admission and graduate, the impacts of neoliberal transformations together with the role of the commercial world and industry in influencing research – the corporatization of public universities – animate the problem of academic freedom in postcolonial universities. These affect and continue to define the institutional cultures together with the role of research funding, and how they close down or enhance spaces for free speech in these universities.

My consideration of the future of the universities in Africa is informed by the material conditions and political economy constraints of the states on the continent. These are illustrated by the harsh impact of the climate crisis in Central Africa, East Africa, the Horn and the Sahel;Footnote 9 the conflict dynamics in Cameroon, Democratic Republic of Congo, Mali, Niger, Nigeria and Somalia; declining national currencies and revenues;Footnote 10 dependent national economies; soaring debt profiles; and other effects of state dysfunctionalities raging unabated. These continue to undermine the attention accorded to healthcare, higher education and other social services. Africa is not alone in this misadventure: Latin America, South Asia and other low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) share similar misfortunes and statistics with Africa. Statistically, the African context is gloomier than elsewhere. This partly explains the incapacity of home-based African academics to independently set research agendas. They underline the poor research infrastructures in African universities (Mills Reference Mills2025) and the reduction of African scholars to local data gathering in the global system of knowledge production.

There are other illustrations of the crisis of the postcolonial universities. Examples of such failings include the abandonment of autochthonous, endogenous and indigenous knowledges, and the failure to Africanize the neocolonial universities and build a new humanism premised on restoring dignity to Black identity through the transformation of postcolonial subjects from their cultural and structural dependency as overseas products and representatives of the universities in post-Enlightenment Europe (Fanon Reference Fanon1952; Reference Fanon1961; Reference Fanon1964; Mazrui Reference Mazrui1992), among other disappointments of decolonization and the limitations of nationalist elites. From the 1980s, the failures of African universities have been connected to those of the states. As international attention accounted for what went wrong with Africa (World Bank 2000; Veen Reference Veen2004), much energy was sunk in the search for alternative frameworks for affirming the continent’s economic and political development. The problematic character and nature of the state in Africa – together with the impossibility of doing without the state while also not doing well with it – have been widely acknowledged by scholars in the literature. The defining problem has been the neglect of the universities by states. The telling impacts of this neglect, together with the repression of academic freedom, have been accounted for in the literature (Arowosegbe Reference Arowosegbe2016; Reference Arowosegbe2021; Reference Arowosegbe2023). In the postcolonial universities, the devastations of this crisis together with the failed responses to them are illustrated in the failure by African intellectuals to reinvent and transform the inherited colonial character of the post-Enlightenment universities in the new states. My elaborations on these problems draw largely on Nigeria.

As excruciating poverty mars living conditions in public universities, the federal government remains indifferent, insensitive and non-committal to the deteriorating plight of workers (Akinwole Reference Akinwole2024a; Reference Akinwole2024b; Osodeke Reference Osodeke2024). Threats of unions embarking on fresh strikes fall on deaf ears in state quarters.Footnote 11 The current regime denies responsibility for agreements reached by past governments with university unions. It rather expresses commitment for fresh dialogue and negotiation.Footnote 12 Given the limited internally generated revenue relative to their needs-based expenditures and pathologically poor research funding from overseas sources, public universities in Africa are toiling under immense financial difficulties – unable to pay electricity bills among other running costs and utilities.Footnote 13 With University College Hospital (UCH) Ibadan fast becoming a health-damaging centreFootnote 14 and other university health systems dishing out expired drugs, these universities continue to dilapidate.Footnote 15 Death recordsFootnote 16 and resignation statisticsFootnote 17 are also rising, to the detriment of institutional continuity and productivity.

The empirical problem

My critique of home-based African academics, public universities and the state in Africa is familiar. This should not detain us here. The continued decline of Nigeria’s first-generation universities evidenced by the downward plunge of the University of Ibadan and other Nigerian public universities in African and world rankings of universities – followed by the rise of Covenant University, as reported by the 2024 Times Higher Education – sorely confirms my claim that public universities in Africa are in crisis (Arowosegbe Reference Arowosegbe2023).Footnote 18 In Nigeria, beyond governmental neglect and state repression, the integrity of these universities continues to be undermined by a range of other challenges: academic compromises and corruption by lecturers and students; clientele-patronage politics; problematic and toxic collegiality; the appropriation and instrumentalization of office for bureaucratic aggrandizement and cake-sharing in the allocation of contracts and resource control through appointments, promotions and recruitments; and the resort to consultancy, neo-patrimonialism and other internal practices. Academics in all of Nigeria’s public universities are getting promoted. Appointments and promotions committees are uncritically awarding prima facie approvals to all promotion applications. Nigerian academics perform poorly in their capacity for generating non-governmental funding for their research. This explains their dependence on state salaries for survival. This dependence illustrates their vulnerability to state control and impositions. It reduces the clamour for academic freedom and the struggles by academic unions for university autonomy to empty rhetoric. Administrative assignments and predatory publishing have been normalized as short-cut strategies to full professorship in all the first-generation universities. These practices have become popular culture and now define the shoddy scholarship taking root in other public universities.Footnote 19 Internationally, none of Nigeria’s public universities are advancing any measurable investment beyond the local ranking by the National Universities Commission (NUC) and other internal sources.

Most professors are queuing and scheming for positions – as deans, directors, provosts and vice chancellors – in these universities. Regretfully, these neither understand the systemic problems nor how to restore and transform the universities to meet competitive world-class standards. Barring their opportunistic access to official cars, the allocation and determination of contracts and other kickbacks from their lucrative idleness, there is no justifiable explanation for the ruthless quest for administrative and political power in these universities. After several decades of post-independence existence, evidence regarding Nigeria’s premier and other first-generation universities suggests continued decline in academic capacity and governance quality – underlined by empty delight in the years of past glory. The illustrious academic and intellectual traditions bequeathed to the postcolonial universities as overseas extensions and representations of the universities in Europe and North America that established them have been lost. The proud histories of the postcolonial universities are not corroborated by the disconnection with their local communities and the increasing dynamics of their ongoing failings. They have been overrun by irredentist and other institutionally destructive pathologies.

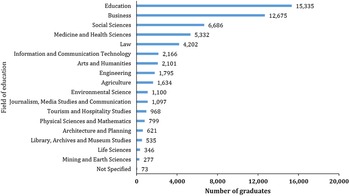

The worst impact of the crisis in African universities is on the employability, skills and training of their graduates. University degrees are meant to open more doors than they close. However, given the disconnect in university curricula between course content and market needs, disciplinary orientations and training, this expectation is deeply problematic. The record numbers of high-flying graduates produced by Nigeria’s private and public universities are not complemented by either applicable entrepreneurial, independent skills or market-ready transformative training.Footnote 20 In a national outburst in 2014, Yoweri Museveni described the arts courses in Uganda as useless, and lamented as unfortunate the continued focus on such disciplines that end up delivering postgraduation joblessness (see Juma Reference Juma2014). In her study on East Africa, Anna L. Mdee (Reference Mdee2024) argues that the expansion of national education and public universities over the past twenty-five years has not significantly contributed to national transformation in Kenya, Tanzania or Uganda. She describes a ‘financial and intellectual dependency dilemma’, ‘market demands for STEM graduates – neglected by the universities’ and the ‘skills–employment dilemma’ as postcolonial illustrations of colonially rooted structures undermining national education in East Africa (see Table 1 and Figure 1). She observes that, given this gap, many of the graduates produced in record numbers from this process – agricultural extension workers, engineers, lecturers, medical doctors and teachers – are not absorbed into formal employment at commensurate rates (see also Fonn et al. Reference Fonn2018; Cochrane and Oloruntoba Reference Cochrane and Oloruntoba2021; Kibona Reference Kibona2024). With about 87 per cent of graduates across the states battling with unemployment, the incentive for university education has largely diminished among the youth.Footnote 21 Africa’s unemployable graduates are products of its decadent and impoverished institutions. Continued relocation overseas by qualified manpower continues to worsen the situation (Makoye Reference Makoye2023; Sirili Reference Sirili2018). As Mdee (Reference Mdee2024) recalls, the fatal crisis and impact of ongoing emigration by medical personnel – doctors and nurses – in the health sector in East Africa are telling. Far from subsiding, the casualties and deaths are escalating.

Table 1. Gross enrolment ratio for tertiary education in East Africa by gender

Source: Afrobarometer statistics on unemployment; see also Savage (Reference Savage2024).

Figure 1. Graduates by their fields of education in Tanzania (2022)

Source: Tanzania Commission for Universities (2023: 28).

In his Theses on Feuerbach, Marx (Reference Marx1845) noted that other philosophers had merely interpreted the world. The point, however, is to change it. Changing the problematic trajectory of public universities in Africa demands transforming them to produce Fanon’s (Reference Fanon1952) new humanism at all levels of citizenship education. This means addressing the disarticulated character of African economies and the statist nature of their political systems. It is to democratize access to national and public education – at all levels – as a strategy for boosting the production of national economic surplus, thereby restoring political integration; faith in the political community and social contract; and the sense of a common will. It means enhancing the universities’ capacity and contributions to the development of indigenous local capital and productive forces in the regions on a globally competitive scale. It should also halt the continent-wide dependence on the West in which the prescriptions of academic needs and programmes by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank and other external authorities continue to destroy African capacity to develop critical thought and independently set original research agendas. I illustrate this below.

Historical context: the case for decolonization

The contradictions in Africa’s educational system are irresolvable within the existing economic and political systems that are structurally colonized and technically steered from abroad. As with its civil wars and violent conflicts, accentuated inequality and poverty, debt distress, high unemployment, low productivity and other problems in Africa’s educational systems are manifestations of deeply rooted dilemmas that are connected with its colonial background. Colonialism left behind divided and fragmented societies – with ideologies of divisionism, poor infrastructures and weak institutions in Africa and in the global South more broadly. From the post-independence period to date, the structural traps imposed on the continent have reduced its contribution in the global capitalist system to the consumption of industrial outputs and technologies from the global North; the outsourcing of obsolete technologies – no longer needed in the North – in the name of development cooperation, job creation and technical assistance; and the supply of cheap raw materials. In knowledge production and research, this takes the form of exporting theoretical knowledge from the global North and supplying data by African academics and their universities. As various neocolonial operations continue to undermine Pan-Africanism’s capacity to produce its own liberation, these realities underline decolonization, nationalism and postcolonialism as uncompleted projects in Africa.

The twentieth century was marked by many geopolitical transformations. In this period, several shifts have taken place in global political economy and world history. Empires have risen and fallen. World Wars One and Two – and the Cold War – have been fought. In 1900, London was the centre of the world. There was no Communism, no Soviet Union. There was the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Ottoman Empire. The United States of America was largely isolationist and stayed on its own side of the Atlantic. By the 1940s, England was demolished by the World Wars. The Ottoman Empire was dissolved. The Soviet Union emerged while Germany took over France. These events were followed by other unprecedented developments. The 1980s and 2000s illustrated substantially different global pictures. These changes make certain historical continuities rather astonishing. Amid the radical changes that swept over every element of international relations, the West’s relationship with Africa has remained unchanged. This continuity explains the paramount nature of that relationship for the West. Over the past 800 years, this relationship has been ruthlessly extractive. This remains the case even in the twenty-first century. The importance of this relationship underlines the necessity of its preservation by the West. As Samir Amin (Reference Amin1972; Reference Amin2014), Walter Rodney (Reference Rodney1972) and Immanuel Wallerstein (Reference Wallerstein1974) have shown, the West’s continued impersonation of a superior civilization in economic development, knowledge production, material progress, military technology and state building is not based on its acclaimed intellectual, moral or spiritual superiority. Rather, it is premised on the West’s exploitative subjugation of Africa and the violent extraction of its human and natural resources. This underlines the unequal trade relations between the two regions – in which Africa has been permanently reduced to raw material production: cash crop production under colonial rule and raw material extraction in the postcolonial period, with manufactured products and technology coming from the West. In knowledge production, African academics and African universities have been reduced to data generation while philosophical knowledge and seasoned theoretical reflections and thought have remained the exclusive preserve of the industrialized West.

The most visible illustration of these problems is Africa’s external debt – debt denominated in foreign currencies. The structural adjustment programmes (SAPs) began in the late 1980s and were intensified in the 1990s; from 2000 onwards, the practice has been for the states in Africa to plunge their economies into unregulated external debts and foreign loans without undertaking debt sustainability analysis.Footnote 22 This takes a huge amount of fiscal policy space that constrains African governments from investing in basic health, infrastructure, public education and other building blocks of development and prosperity. This derives from the commitment to prioritize paying back the external debt. External debt, however, results from deeper structural tensions that have colonial roots – deficits in energy, food and manufacturing.Footnote 23 As a mark of its economic disarticulation, Africa consumes what it does not produce and produces what it does not consume.Footnote 24 This explains its marginal position in export orientation relative to its high import profiles. It underlines the food insecurity across Africa and the global South. This gives birth to a global value chain that keeps Africa and other LMICs in Latin America and South Asia in permanent deficit situations. The combined effect of these arrangements produces trade deficits across these regions. Trade deficits are best understood in terms of their value-added content systems in which the value of exports from the global South is low while the value of its imports is high. As Africa remains locked at the bottom of the global value chain, its structural trade deficits depreciate the continent’s currencies relative to the US dollar and other foreign currencies. With weakened national currencies, critical imports – food, fuel and medicine – are procured at very high prices. In this asymmetric arrangement, Africa imports inflation in the most sensitive areas of its economies, thereby hurting the most vulnerable segments of its populations. The resort to protectionism – that is, the national drive to preserve the existence of poor citizens – leads African governments to subsidize food and other imported necessities. This is unsustainable over the long term. State withdrawal from protectionist policies forces African farmers out of agrobusiness.Footnote 25 As African governments invite their central banks to contain inflation and stabilize exchange rates, this is often pursued using a band-aid approach that further relies on borrowing more US dollars and keeps external debts in an unsustainable vicious circle. This forces African governments to prioritize economic activities that enable them to rapidly earn more forex and thereby service their debts. This, however, deprioritizes basic health, public education and other transformational activities that are central and foundational to development and prosperity. This neocolonial architecture partly explains the continued neglect and underdevelopment of Africa’s public universities.

From the mid-1980s public education as a public good has been neglected by the state in Africa. I have argued elsewhere, following Joan W. Scott (Reference Scott2019), that higher education provides humanity with a shared public good, a set of benefits that advances the common will and well-being of the nation (Arowosegbe Reference Arowosegbe2021: 278–82). National education is, therefore, a core obligation of the democratic, modern state. It is a legitimate demand by the citizenry. As part of private property, private education, at all levels, should at most complement public education. It must never be deployed as a replacement for public education. The early post-independence elites pursued this path of national education. This grounded articulation, prioritization and understanding of public education as a common, public good has, however, been jettisoned by the postcolonial state. With the commercialization, liberalization and privatization of higher education as recommended by the major international economic institutions – IMF and the World Bank – together with the introduction of SAPs and other macro-economic stabilization policies, the attention once accorded public education has been lost. Market-driven, neoliberal, profit-oriented policies currently determine the state’s investment in higher education in Africa. The government’s agenda in Nigeria is aimed at outright privatization and total withdrawal of state involvement in public education. Not surprisingly, from the 1990s, Africa’s defence expenditures and other state investments in Western-produced military hardware and technologies have continued to rise and soar beyond agriculture, education, health and infrastructure put together.Footnote 26 These dynamics and the problem of state capture continue to undermine the equitable and just distribution of national resources and wealth.

Conclusion

Given its context, the decline of public universities and rise of private universities spell doom for the future of public education in Africa. An educational system dominated by private capital can take root only in an imposed future on the continent. This cannot be based on popular will. Nor will it happen as an agreeable, democratic decision premised on the popular consent of the people. This will reverse the achievements of the early post-independence period when national education minimized discrimination – by age, class, ethnicity, gender and race. Drawing on the French Revolution’s Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–97) (Reference Wollstonecraft1790) advanced an early defence of the idea of individual rights based on reason and advocated the importance of national education to the intellectual, moral and spiritual development of modern society. Arguing that merit is the best justification for private property, she critiqued custom, hereditary systems and tradition as mechanisms for projecting inequalities in hierarchy, position, power and wealth.Footnote 27 She presented national education based on universal ideals of merit, rationality, reason and virtue as the best foundation for a fair and just society. This is key for building a free, non-discriminatory and non-hierarchized society based on an identification with humility, national uniformity and shared interests and purpose. Freedom is the essence and meaning of politics. Modern revolution must establish a form of politics and state capable of securing human freedom. It must offer humanity the opportunity to explore the possibility and reality of a new beginning (Arendt Reference Arendt1963).

The future of public education in Africa is bleak and unprotected. The failure of the postcolonial elites to transform the inherited structures of colonial society underlines the withering away of the state in Africa – Fanon’s (Reference Fanon1961) thesis on the dangers of decolonization and pitfalls of national consciousness. Given the lack of redemptive capacity and will on the part of states, the sector might not survive threats from domestic competitors and other externalities that are looking forward and working hard towards its collapse. The most serious threat to national education in twenty-first-century Africa is the externally suggested financialization of higher education and public universities. The neoliberal agenda of the IMF and World Bank to commercialize and liberalize public education through the ruthless privatization of this sector is not likely to be halted. Rather, the entry of China and other international actors as active players in this sector will continue to undermine self-determination and weaken state sovereignty through aid dependence and external debts. The active presence of Chinese Confucian Centres and other culturally loaded programmes by new active international players – preying on the limitations in funding available to state institutions in East Africa – is an illustration of the continuity of external influences. These will leave the continent with little manoeuvrable policy space for independent action.

Within African states, governance failure – illustrated by conflict, debt peonage, poor service delivery and state dependence – will neither allow nor encourage focused funding of public education. In 2024, rising public debts, exacerbated by limited fiscal space and multiple shocks, pose a significant challenge to Africa’s development. Ghana, Malawi, Nigeria, South Africa, the Republic of the Congo, São Tomé and Príncipe and Zambia are among the most indebted states in Africa (Were Reference Were2024).Footnote 28 Unlike the debt crisis of the 1980s, which was largely driven by multilateral debt, the current public debt comprises mainly bilateral and commercial debt. This follows increased access to international financial markets and China’s emergence as a significant source of bilateral credit. This debt attracts higher interest rates; it is costlier; and it is subject to higher interest rate volatility than the concessional multilateral debt of the 1980s. It is thus more difficult to either negotiate or pay off. Debt servicing undermines national planning in Africa.

Within the universities in Africa, there is no foreseeable action to arrest the ongoing dynamics of collapse. This situation is highlighted by the corresponding collapse of national institutions of indigenous knowledge valorization on the continent. African universities remain increasingly alienated, with diminished relevance to their immediate societies. In Nigeria, the internal decay of public universities and their neglect by the state are sharply contrasted by the aggressive injection of funding into private universities by their owners and stakeholders. As research and teaching infrastructures continue to collapse in public universities; as African academics continue to respond poorly in generating non-state-dependent, international funding for their research; as the National Association of Nigerian Students (NANS) and other national students’ union bodies continue to compromise their popular mandate, lobby and work as government spokespersons and stooges; as pliable and willing members of the Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU) and other national academic unions continue to collaborate with state officials for self-preservation and survival to the detriment and neglect of core institutional and societal interests; and as university administrations continue to be dominated by reckless, shady characters and beneficiaries of perilous impunity, these developments might all entrench the beginning of the collapse of national, public education and the end of public universities in Nigeria and elsewhere on the continent. Whither the future?

A number of factors are likely to constrain the efforts of the continent’s private universities towards improved performance in future world university rankings. These might limit Nigeria’s private universities from rising beyond sub-Saharan Africa universities’ rankings. To be sure, these universities generate their highest points through their acquisition of cutting-edge laboratory equipment, libraries and other facilities needed by modern universities. They also perform much better in funding their faculties at international conferences. However, it takes more than facilities and funding to improve one’s ranking among world-class universities. The third and most important factor is the quality of the faculty.

Unfortunately, given their continued violations of academic freedom (Arowosegbe Reference Arowosegbe2024) and violent conflicts – due to al Qaeda and Boko Haram insurgencies in Nigeria and the SahelFootnote 29 – beyond data gathering, fieldwork and other marginal collaborations, world-class academics and students will hardly be attracted to study or take research and teaching positions in these universities. Nigeria’s private universities are not paying globally competitive allowances and salaries. They can therefore hardly attract some of the best overseas-based and overseas-trained academic workforce (Proverbs 22.29, KJVFootnote 30). Predictably, for the next half century, the fate and fortunes of these institutions will depend on the families and inheritance patterns of their ownership structures. These neopatrimonial networks will neither democratize nor make room for the normal functioning of these universities.

As I indicated earlier (Arowosegbe Reference Arowosegbe2010), beyond the euphoria of past glory, it is time for home-based African academics and the postcolonial universities to reclaim the illustrious heritage of the early post-independence period and retrieve the lost visions of Black consciousness (à la Biko) and Pan-Africanism, both of which are indispensable to produce Fanon’s (Reference Fanon1952; Reference Fanon1964) new humanism on the continent.

Acknowledgements

The production of this article benefited from the discussions at the panel on ‘The Political Economy of Public Universities in Africa: Funding, Strikes, Students’, which I convened on behalf of Africa at the African Studies Association of the United Kingdom (ASAUK) conference held at Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, 29–31 August 2024. I am grateful to Brendon L. Nicholls and David Mills for their comments and support.

Jeremiah O. Arowosegbe teaches Intellectual History, Political Theory and African Studies at the University of Leeds. He is working at present on two books: Autochthony, Democratization and State Building in Nigeria and Universities and State Regulations in Africa. He is commissioning and editing a collection of essays titled Academic Freedom, Universities and the State in Africa.