Introduction

On the first Saturday of August each year, a great number of Oka people gather on the ground outside the palace of the king of Oka-Akoko.Footnote 1 This event, called Oka Day, lasts from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. and consists of a series of activities, particular features being the ceremonial prayer to the ‘New Yam’, the conferring of honorary chieftaincy, the announcement of donations from various guests, and cultural performances. At around 11 a.m. on 4 August 2018, the first high-profile event of that year's Oka Day came with the arrival of the king – Yusuf Adebori Adeleye. Followed by a group of palace staff and close relatives, the king, dressed in Yoruba traditional attire symbolizing prestige and excellence, slowly stepped down from the highly decorated palace on the top of a small rocky hill. Lining the way, attendees bowed and exclaimed, ‘Kabiyesi!’ (Your majesty!). The king nodded to people from his royal canopy and softly chanted prayers, signalling his acceptance of the people's greetings.

Despite its historical relevance to various New Yam festivals in Oka, the emergence of Oka Day is closely associated with the king. It was formally established as an annual ceremony in the early 1990s, soon after Yusuf Adebori Adeleye assumed the royal title of Olubaka and took the position of kingship in Oka. In his own words:

When I became Oba (king), I was looking for an avenue to bring the people together under a common platform. In the past, different quarters celebrated their New Yam festivals at different times … I thought we should have one common celebration that brings us all together. That's how we came about celebrating New Yam and Oka Day festival on the first Saturday of August. (Offiong Reference Offiong2014)

In recent decades, this kind of community day celebrations has taken place in many local contexts in Yorubaland, such as the Imewuro Annual Rally,Footnote 2 documented in 1986 (Drewal Reference Drewal1992: 160–71), the Iloko Day, studied in 1993 (Trager Reference Trager2001: 15–36), and community development festivals in Remo (see Nolte Reference Nolte2009: 221). Existing research interprets this phenomenon in two ways. The first is to treat the community day as a festival and delves into the performative politics implicated in festival activities (Drewal Reference Drewal1992). In Yoruba cultures and histories, festival performances involve power politics transmitted from the Nigerian state to local customary authorities (Willis Reference Willis2017). The second way is to focus on community dynamics in which these festivals and ceremonies serve as a civic venue in which to gather different groups of people and all kinds of resources (Trager Reference Trager2001; Nolte Reference Nolte2009), as claimed by Oba Adeleye; in this way, a certain collectivity is developed (Barkan et al. Reference Barkan, McNulty and Ayeni1991; Honey and Okafor Reference Honey and Okafor1998). Both strands of literature, based on different theoretical perspectives,Footnote 3 have shed light on details of how these festivals are performed and how community activities are organized. It should be noted that, from their inception in the 1980s and the 1990s to their presence in 2019, these community day celebrations have been constantly held in Yorubaland, especially in Oka, where there is never any suspension of Oka Day. A constructivist interpretation that emphasizes how these events facilitate community development and identity construction does not fully clarify how community day ceremonies involving various tensions and conflicts can continue for so long. Thus, we suggest exploring different actors’ micro-deployments of power and how these practices matter for the institutional establishment of a community day in relation to chieftaincy institutions.

Adopting an institutional perspective, we argue, works better to interpret the case of Oka Day than treating community days as single events or local initiatives to facilitate community development. Institutions are understood here as ‘the humanly devised rules that constrain or enable individual and collective behavior’ (Beall et al. Reference Beall, Mkhize and Vawda2005: 759). In this case, Oka Day does not just appear as a singular event on the specific date but as a multistage and multifaceted institutional programme that is designed, discussed and prepared for a whole year, involving not only the king and the organizing committee but also quarter chiefs, social clubs, diasporic groups and various levels of politicians.

The institutional perspective also echoes the existing literature that examines chieftaincy institutions in Africa (e.g. Harneit-Sievers Reference Harneit-Sievers1998; Beall et al. Reference Beall, Mkhize and Vawda2005; Bob-Milliar Reference Bob-Milliar2009), especially the politics of Yoruba chieftaincy (Apter Reference Apter1992; Nolte Reference Nolte2002; Vaughan Reference Vaughan2006). The initiative of Oka Day, like many other community days, is highly related to kingship and chieftaincy, but, over time, it has evolved institutionally as different power-laden stakeholders, including but not limited to the king and chiefs, have confronted each other and negotiated in nuanced ways. To articulate the ‘resurgence’ of chieftaincy (Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2018) in the evolving institution of community day in contemporary Yorubaland, we argue that the exercise of power should be taken seriously.

From this angle, Oka Day not only demonstrates the power of kingship as the opening paragraph implies; it also overshadows nuances of power relationships among the organizing committee, chiefs, politicians, social clubs and diasporic groups. In critical geographies, powers, from a Foucauldian perspective, are interpreted in a plural form by refusing to regard power as a unitary and homogeneous thing (Allen Reference Allen2003; Sayer Reference Sayer2004). Thus, powers are not abstract but reified in the practices and discourses involved in the processes of mobilizing material interests and negotiating symbolic meanings. In this research, we elaborate on the ways in which Oka Day is temporally and spatially institutionalized with regard to kingship, chieftaincy and the ‘community’.

Revisiting chieftaincy institutions and politics

Early studies of chieftaincy were built on the concept of binaries, represented by Mamdani's ‘citizen versus subject’ (Reference Mamdani1996): in the colonial era, direct rules excluded Africans from civic freedoms guaranteed to ‘citizens’, while indirect rules incorporated indigenous people into customary laws enforced by native authorities, namely kings and chiefs. Given the merit in this interpretation of chieftaincy and colonialism, this binary conception has been interrogated in many contexts, especially more recently by scholars who have called for an understanding of chieftaincy as a rising power arena in contemporary global political economy (see Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2018).

Following the call to revisit chieftaincy, this case study of Oka Day illustrates ‘a struggle over the disposition of customary power with new means under new circumstances’ (Geschiere Reference Geschiere, Comaroff and Comaroff2018: 74), while echoing three aspects of literature on kingship and chieftaincy in Yorubaland and beyond. The first, represented by Apter (Reference Apter1992), focuses on the dialectic interaction between power and authority in Yoruba chieftaincy institutions. In his definition, power sui generis is inherently anarchic and must be transformed into authority to be controlled effectively (ibid.: 73). Multiple actors, including kings, chiefs and big men, deploy powers to maintain their authority. For instance, in some circumstances, senior traditional chiefs, in contrast to administrative chiefs appointed by kings and colonial authorities, boycotted the king or deposed him if he overruled their collective will (ibid.: 83). When the British appropriated the ultimate right to depose kings, these senior chiefs reacted at the prompting of disaffected chiefs (ibid.: 84). Indebted to this account of the interactions between kings and chiefs in the colonial era, this article further discusses the multiplicity of interactions in the contemporary institution of Oka Day.

The second aspect of the literature elaborates on how chieftaincy was involved at all levels of Nigerian politics in the postcolonial era. The military rulers in the 1960s and 1970s treated kings and chiefs as intermediaries between military regimes and local communities (Vaughan Reference Vaughan2006: 120–37). When electoral politics in the Second Republic (1979–83) thrived, ethno-regional identities invoked by kings and chiefs at the community level facilitated the formation of political parties, such as the Unity Party of Nigeria, which drew the bulk of its support from Yoruba-dominated states (ibid.: 155–93). In this sense, traditional authorities no longer just inform the hierarchies of the local administration but also become more associated with political powers at the state and federal levels (Nolte Reference Nolte2002), and thereby may affect democratic regimes, as in South Africa (Beall et al. Reference Beall, Mkhize and Vawda2005).

The third aspect specifically examines the changing roles of chieftaincy and kingship in Nigeria's community governance and development. One viewpoint attributes the failure of postcolonial Nigerian government programmes to the underutilization of kings’ and chiefs’ powers in local governance (Vaughan Reference Vaughan1995). In the battles with economic crises after the Second Republic, Yoruba local elites, including kings, chiefs, entrepreneurs and self-initiated organizations, launched fundraising activities through community day celebrations, establishing community banks and investing rapidly devalued currency in infrastructure construction in their communities (Trager Reference Trager2001: 145–204; Nolte Reference Nolte2009: 220–8). Oka Day is one of these initiatives.

This research echoes these strands of literature by examining the institutional dynamics of a community day that involves: the Yoruba chieftaincy institution, as Apter (Reference Apter1992) theorizes; the interactions between chieftaincy and electoral politics, as Vaughan (Reference Vaughan2006) outlines; and the role of chieftaincy in community development, as Trager (Reference Trager2001) and Nolte (Reference Nolte2002) illustrate. These scholars have contributed to general understandings of chieftaincy institutions and politics in Yorubaland, but their theories do not specifically and sufficiently interpret how a community day becomes a long-standing institution in which multiple actors constantly interact with each other. More specifically, regarding the third aspect of the literature, Oka Day is not just constructed as a platform where stakeholders mobilize economic and political resources for their own interests and/or a sense of ‘community’. The following account of the backgrounds of Oka and Oka Day demonstrates how this puzzle remains unsolved in the constructivist vein and why we should focus more on practices of powers.

Oka and Oka Day

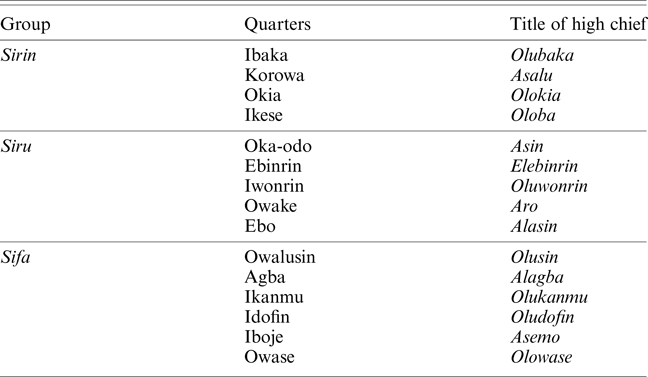

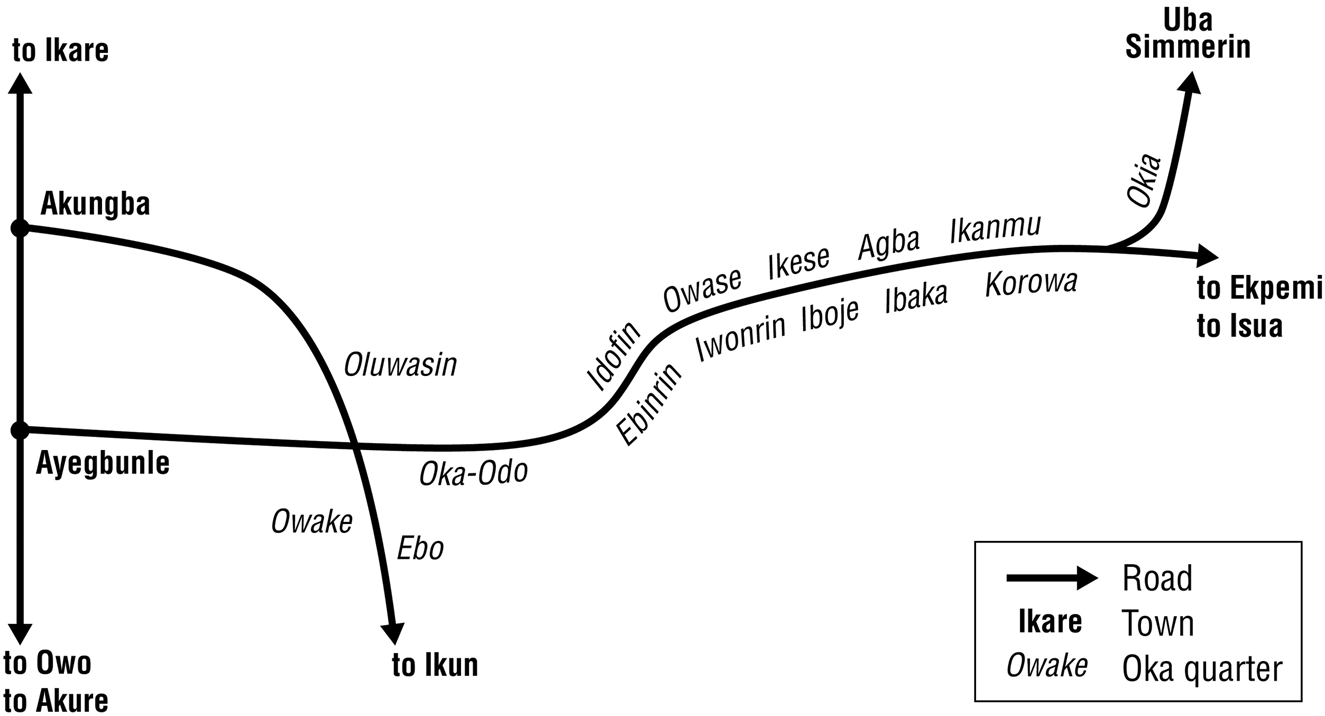

As the administrative headquarters of the Akoko South-West Local Government of Ondo State, Oka-Akoko is situated in a rocky region, about ninety kilometres to the north-east of Akure – Ondo State's capital – and along a major road linking south-western Nigeria to Abuja, the capital. On the periphery of Yorubaland, Akoko region is a meeting ground for diverse peoples and cultures from the core Yorubaland, Igboland, Edo and Kogi states. The Yoruba language, however, serves as the lingua franca, while each quarter speaks its own dialect with identifiable variances. According to oral traditions, Oka was built on the settlements of migrants from Ile-Ife, the supposed cradle of Yoruba peoples (Olukoju Reference Olukoju1993). It is also said that there were three waves of migration to Oka-Akoko during the precolonial era, which are categorized in three groups: sirin, siru and sifa. Each group settled in different quarters (see Table 1 and Figure 1), and these fifteen quarters later became more autonomous, governed by their high chiefs.

Table 1 Oka quarters and the titles of their high chiefs.

Figure 1 The quarters of Oka-Akoko.

According to Kolawole (Reference Kolawole2009), a local historian, Olubaka – the high chief of the Ibaka quarter – is the leader of the sirin group, while Asin of Oka-odo leads the siru group, and the sifa group, which is regarded as the most recent to settle, is headed by Olusin of Owalusin. Dates of arrival figure prominently in the strength of claims by high chiefs to leadership of the whole Oka region (Olukoju Reference Olukoju1993).

Competition for paramount traditional authority was predominantly active between Asin and Olubaka from the late nineteenth century to the early twentieth century. As an earlier paramount traditional ruler of Oka-Akoko, Asin had been supported by the colonial administrators. However, due to local protests against colonial taxation and more frequent communication between Olubaka and the colonial administrators, the kingship of Asin was gradually replaced by Olubaka (Olukoju Reference Olukoju1993: 256–9). The ascendancy of Olubaka therefore became legitimate under British colonial laws. Also, the Olubaka had support from at least eleven out of the fifteen quarters, making the Olubaka's position stable for a long time. The current dynasty, which has been in place since 1900, is the sixth successive Olubaka of Oka.

Today's Olubaka, Yusuf Adebori Adeleye, however, gained the authority to govern the Oka region after a series of battles with the Asin. In 1986, the Asin at the time, Lawrence Obaniyi Omorinbola, went to court to challenge the paramountcy of Olubaka over Oka. This lawsuit underwent a complicated procedure, going from the High Court of Justice in Akure to the Supreme Court of Nigeria in Abuja. The judgment was finally made on 18 December 1998 that Olubaka is the sole paramount king of the whole Oka region.

According to his biographers, Oripeloye and Sanni (Reference Oripeloye and Sanni2009), Adebori Adeleye was born in 1945 in the Ibaka quarter of Oka. In his early years, Adeleye was enlisted in the Nigerian police and worked for the Lagos State judiciary after studying law at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. Despite his flourishing career in Lagos, he was involved in the competitive politics for the title of Olubaka in his hometown of Oka. As a son of a royal family, he was persuaded by his family to participate in the competition, which involved sixteen candidates from nine branches of royal lineage, in 1984. On 9 December 1987, the selection was officially announced by the committee of high chiefs in Oka town hall. Although Asin Omorinbola had already launched lawsuits, the new Olubaka – Adebori Adeleye – was recognized by the Ondo State government on 16 April 1988.

Like many other kings in Yorubaland, Oba Adeleye was faced with economic recession in the 1990s and social disintegration within Oka's quarters, especially Oka-odo, led by Asin. Having lived in Lagos for years, he decided to establish a channel to bring various resources from outside to this less-developed town. Oka Day was invented in this context. From his perspective, the Oka Day celebration is not only a channel to raise funds that facilitate community development but also a venue to unify the community under his newly established authority.

The first Oka Day was held in 1990 in Oka town hall, but it was not called ‘Oka Day’. The objective of this ceremony was clearly written on the cover of the programme: ‘Oka-Akoko 10 Million fundraising for Oba's palace.’ Due to the long absence of the Olubaka position as a result of the protracted competition, Olubaka's palace had not been maintained for years. Therefore, building a new palace, in Oba Adeleye's opinion, meant rebuilding the prestige of Olubaka. The construction took decades, with funds gradually being raised in the process. In 1999, the theme of celebration changed to Oka's development and ‘Oka Day’ first appeared on the programme. The current Oka Day has incorporated a series of week-long activities, including interschool football matches, free medical services and religious activities in different churches and mosques, which were never part of a traditional version of the ‘New Yam’ festival.Footnote 4

This introduction to kingship and chieftaincy in Oka demonstrates interactions between kings and chiefs, between traditional authority and civic government, and between Oba Adeleye and stakeholders. Oka Day was indeed constructed to bring in resources and capital for community development, but the continuity and evolution of this initiative in the context of long-standing tensions and conflicts in Oka history draw our attention to power dynamics other than material interests and ‘development’ discourses.

Methodology and framing

The fieldwork was conducted by two authors across five years. The first author, a non-Nigerian geographer who can converse in Yoruba on a daily basis, attended Oka Day four times from 2015 to 2018. The second author, a native Yoruba historian originally from Oka-Akoko, attended Oka Day in 2018 and 2019. Apart from participant observation in an array of Oka Day activities, we conducted in-depth interviews with Oba Adeleye, chiefs in ten of the fifteen quarters, and active members of the Oka Day organizing committee. The content of interviews covered the oral traditions of each quarter, the perceived changes of Oka Day since its inception in the 1990s, and interviewees’ experiences as participants over the years. During the events, we also conducted informal interviews with youth leaders, women's group representatives and a variety of ordinary attendees who view the events at a distance. These interviews were primarily conducted in English, but some ritual aspects of interviews were conducted in Yoruba and translated by the second author to English. This grounded fieldwork was supplemented by the collection and content analysis of Oka Day programmes and brochures from 1991 to 2019. Collaboration between two differently positioned scholars is advantageous in the context of reflexive attendance to nuanced power dynamics, which can be overlooked by either outsider or insider researchers.

In the discussions and reflections between the two authors during and after fieldwork, the research focus on powers – the plurality of power practices and effects, as we define it – was further emphasized through the following research question: how are powers exercised by actors in a web of relationships to establish and maintain an institution of powers in the case of Oka Day? To answer this question is to tease out ‘the microphysics of customary authority’ (Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2018: 17), and what matters is a spatial thinking of powers.

Here, the spatiality of powers refers to the mobilization of distant actors into the locality of the power regime. Geographers have suggested thinking of powers as relational effects of social interactions and exploring how power relations are constituted not in abstraction from space and time but through spacing and timing (Rose Reference Rose1997; Allen Reference Allen2003; Massey Reference Massey2005; Crampton and Elden Reference Crampton and Elden2007). Therefore, in our fieldwork, we not only paid attention to spatial arrangements of things and activities but also delved into spatial relationships among different actors. Examining these spatialities through the temporal change of Oka Day during our consecutive attendances over the course of five years helps us clarify how the spatialities of powers become institutionalized in the contexts of tensions and conflicts of interests.

After qualitatively analysing our field data and notes, we found a framing of ‘powers of reach’, as proposed by John Allen (Reference Allen2003; Reference Allen2011; Reference Allen2016), very informative and particularly useful to interpret spatialities of powers in the case of Oka Day. Built on Latour's and Foucault's works, Allen (Reference Allen2003; Reference Allen2011: 292) suggests that power is practised by actors to ‘make their presence felt’ in and beyond specific regions or localities. The concept of ‘reach’ refers to a strategic model of power in which actors act for a range of ends through distanced linkages. This framing has been applied and critically discussed in many case studies, but it works well in interpreting a litigation-driven campaign for redress by the South African social movement, the Khulumani Support Group, that draws on the utility of a US legal statute (Akinwumi Reference Akinwumi2013). Similar to this case, and not just a (re)presentation of traditional cultures in a local sense, Oka Day draws a variety of resources and actors from the corners of Oka territory and from connections outside Oka to a stage that showcases the centrality of kingship.

This concept is also useful in understanding the institutional establishment of Oka Day, in which the king, chiefs, politicians and different groups act for various ends. Parallel to the South African case, Oka Day can be seen as an institution in which actors mobilize various resources to achieve their goals or react tactically against certain mobilizations. Moreover, Oka Day is not just a ‘traditional’ community event characterized by the presence of a king, chiefs and local residents, but a new form of complex institution that involves actors who live and work beyond the locality of Oka community while having spatial registers in the locale. Thus, in what follows, we demonstrate how the framing of powers of reach fits in to tease out the spatial microphysics of power practices. Bridging geographies of powers and African studies on kingship and chieftaincy, this article contributes an analysis of spatialities of powers to an understanding of contemporary Yorubaland's chieftaincy institutions and politics.

The king and the organization of Oka Day

Reach, in Allen's (Reference Allen2016: 3) framing, is a form of relational distance, not a spatial metric; it is something that has to be leveraged by stretching or folding relationships. Allen (ibid.: 104–27) further elaborated on this idea in accounts of how governments’ and NGOs’ powers are deployed from the centre of institutions to reach in specific spaces and localities. In what follows, we borrow his concept to analyse how the king exercises powers spatially and temporally through the organization of Oka Day.

The king's powers of reach manifest in the invention and organization of Oka Day. In our interviews with Oba Adeleye and in his public speeches on Oka Days, he always emphasized his endeavours to make ‘a united and inclusive community’ for Oka peoples. He tried to bring together fifteen quarters, although the high chiefs of Oka-odo and Owalusin have not accepted his proposal. Also, he tried to gather people holding different religious beliefs on Oka Days. The New Yam festival, a previous version of Oka Day, is usually a traditional ceremony in which people worship indigenous gods and deities, but he separated this worship ritual from public ceremonies on Oka Days. Furthermore, he invited reputable pastors and imams to preach at the ceremonies. To symbolically integrate Muslim and Christian groups, on the Friday before Oka Day and the Sunday afterwards each year, he led some chiefs to pray in mosques and churches respectively. He maintained that Oka Day is ‘a consistent celebration over the years from its beginning, never stopped’. The evolution of the Oka Day celebration is closely linked to the development of Oba Adeleye's authority. He was concerned not only about how his powers are exercised in the territory, involving all the quarters as much as possible, but also about how the effects of those powers can be represented in the ceremonies of Oka Day. That said, he was more concerned about representations of powers of reach on Oka Day, which, he deemed, was created and maintained by himself, to reinforce his authority of kingship. The practices of powers, however, are more complex than a single person's will and deployment.

The organizational institution of Oka Day signposts the spatiality and temporality of powers of reach exercised by an organization. Indebted to Rose's (Reference Rose1997: 4–7) interpretation of the spatiality of power in three aspects, we conceptualize the first dimension of spatiality of powers of reach in this case as the zoning that divides a territory into a centre and the margins. For instance, a physical fitness and health initiative, which has provided Oka residents with free health services during the Oka Day weekly programme since 2016 and was sponsored by Okarufe Club, was usually held in three locations. According to the organizing committee, the selection of these locations considers not only Oka town hall, located in the centre of Oka, but also the periphery (Simmerin sub-quarter, for example) and a site of discontent – the Owalusin palace compound, where Chief Olusin officially works. The second dimension of spatiality is flattened hierarchy. Although fifteen quarters have different power positions in this arena, the emphasis on each quarter being represented in the organizational institution aims to demonstrate territorial ‘unity’ and ‘fairness’. Secondary school scholarships, for example, which are sponsored by funding raised from previous Oka Days, are allocated evenly to two students in each quarter. The allocation is usually announced at the Oka Day ceremony. The final dimension is the size of the community that the person represents: in local terms, ‘if a quarter is small or big’. A ‘big’ quarter, such as Ibaka, Ikanmu Ikese or Agba, usually has more chiefs than ‘small’ quarters, and the chiefs in ‘big’ quarters appear more powerful and active than others. For instance, the members of the organizing committee are supposed to include representatives of all fifteen quarters, but the active members involved in the decision-making process are always from ‘big’ quarters. Under the king's supervision, the committee holds regular meetings in the new palace throughout the year.

The temporality of powers of reach in the organizational institution of Oka Day does not form instantaneously but over the years. Comparing printed programmes of Oka Day in 1991, 1999, 2003, 2010 and 2018, we discovered significant changes of presentation. In the 1991 programme, there is no ‘Oka Day’ on the cover; a fundraising event was highlighted and was held in Oka town hall. In the 1999 and 2003 brochures, the name ‘Oka Day’ appears together with a fundraising advertisement for the ‘Ultra-Modern Palace’ on the cover. That was the period when Oba Adeleye won the lawsuit over the Asin. In 2010's programme, ‘Oka Day’ was highlighted along with the venue of ‘New Palace Ground’. After 2013, when the palace had been constructed, the programmes became more formalized and formatted. According to various members of the organizing committee, Oka Day was initially organized by elder high chiefs from 1990 to 1993. In 1994, an ad hoc committee composed of younger members took over the organizing. The analysis of Oka Day brochures demonstrates that powers of reach are institutionalized temporally when the kingship becomes stabilized and that the organization of Oka Day was dominated by the king's supporters in lower-status positions rather than high chiefs.

The making and unmaking of local cultures

Along the way, as Oka Day was institutionalized, some aspects of local cultures changed. Instead of interpreting these in the frame of ‘invented traditions’, which Comaroff and Comaroff (Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2018) critique, we analyse how the exercise of powers of reach makes spatial relationships ‘twisted’ in a local sense. Allen's (Reference Allen2011) account of powers of reach addresses two points: first, the mediated exercise of powers allows spatial relationships to be twisted; and second, the quieter or muted registers of powers, such as indifference and rejection, respond to the mediated powers of reach. This section elaborates on the first point, leaving the second to be discussed later. The consequences of power practices involve not only changes of cultures or traditions, but – and more profoundly – twists of socio-spatial relationships among various actors. The framing of ‘twist’ in relation to ‘change’ better captures the nuances of spatial practices, especially here in the aspects of architectures, rituals and narratives of oral traditions and histories.

In Yoruba towns, the king's palace (afin) is an edifice that symbolizes the powers of kingship (Kamau Reference Kamau and Rapoport1976: 343–7). The old king's palace, which Oba Adeleye inherited from the previous Olubaka, had been abandoned for years due to lack of maintenance. Earlier Oka Day celebrations were intended to raise funds to rebuild a palace from not only local upper classes but also Oka descendants in the diaspora, especially in Lagos. The construction of the new palace was primarily supported by the Ondo State government, in which Oka-born politician Ajayi Robert Boroffice played a crucial role. It is said that the current grandstand, with a large roofed arcade to shade the king and invited guests on Oka Day, was also constructed by the fund provided by him.

In 2013, the new palace was eventually inaugurated together with a large-scale celebration for the twenty-fifth anniversary of Oba Adeleye assuming the Olubaka title. Compared with previous palaces, which mingled with ordinary houses, the new palace on a small hill in Ibaka quarter, from where the king has a view over people gathering below, signals the significant positionality of Ibaka among all fifteen quarters and is a physical marker of the symbolic status of the king. In a spacious hall inside the new palace, a splendid throne where Oba Adeleye sits in exquisite attire manifests the magnitude of royalty and honour. All these spatial and physical rearrangements of architecture by Oba Adeleye, which are consistent with the principles of Yoruba afin (Ojo Reference Ojo1967) but embodied through modern materials, are intended to underline the distinctiveness of his kingship compared with other high chiefs and previous kings.

Another spatial relationship is twisted between the kingship and the traditions of New Yam festivals. Traditionally, newly harvested yams should be ritualized in the public space in honour of the deity Oko (Coursey and Coursey Reference Coursey and Coursey1971). Instead of performing this ritual before all Oka peoples, farmers and ritual specialists came to practise it indoors as part of Adura Ibile, in front of only Oba Adeleye and some high chiefs. On 31 July 2018, we observed that yams were sacrificed with gin, kola nuts, live goats, palm wine, salt, palm oil and water. This ritual was performed in Yoruba to convey the prayers for Oba Adeleye, chiefs, the Oka town, and all Oka people. On 4 August 2018 – the date of Oka Day – a simple ritual was performed in public: three young girls presented selected yams to Oba Adeleye, who made a brief blessing on the yams. The spatial deployment of Adura Ibile to the high-status attendees and simplification of yam rituals for the public on Oka Day result from the king's exercise of powers of reach. In addition, farmers, who are supposed to be central to the traditional New Yam festival, took on a supporting role to highlight the status of Oba Adeleye. On Oka Day, a group of farmers acting as ‘vigilantes’ parade to greet the king by singing traditional songs. In contrast, in Owake quarter in the periphery of Oka, a brief traditional ritual was performed by farmers surrounding Aro's house the day before Oka Day. These spatial practices were not found in ‘big’ quarters closely associated with kingship.

The most salient spatial twist is on-street masquerading. In traditional New Yam festivals, as well as Iwaro Day,Footnote 5 which is held a week before Oka Day in Oka-odo by Asin's followers, masquerading rituals are extensively performed along the main roads. However, some chiefs and organizers of Oka Day maintained that masquerading is not ‘civilized’ and that large-scale masquerading activities obstruct traffic flows and societal orders. These interviewees appreciated the difference in masquerading between Iwaro Day and Oka Day, and also between Oka-odo and the rest of Oka. For Oka Day, extensive spatial practices of masquerading across quarters have been transformed into intensive spatial representations of ‘cultural performance’ in the palace grounds.

Spatial twists are found in the narratives of Oka history as well. Given the long-standing dispute between Asin and Olubaka, people living in Oka-odo have a different interpretation of kingship in Oka history. They believe Asin should be the only traditional leader of Oka region, whereas former Olubakas seized the power that was granted by the colonizers. Although the current Olubaka, Oba Adeleye, won the lawsuit, they organized their own festival, Iwaro Day, in response to Oka Day. Since the last Asin died years ago, the position has been temporarily taken by his daughter until a new Asin is elected. In fact, not only did Asin claim the paramount kingship of Oka, Olusin of Owalusin recently contested Oba Adeleye's authority. The current Olusin was elected in 2002. Initially he attended Oka Day, but later he decided to organize an independent activity in Owalusin on the same day. Nevertheless, people in Owalusin, including his chiefs, did not strongly support his initiative. In this sense, the seeming spatial unity of Oka is in fact twisted by the tensions among Oka-odo, Owalusin and the rest of the Oka quarters.

In the early years of Oka settlement, according to the oral traditions collected from our interviews, migration trajectories affected the power status of Oka quarters: the earlier people arrived and settled, the more powerful these people were. However, due to agricultural development and population growth, many people settling in hilly areas moved to the lower lands of Oka. For instance, some Ikanmu people – one of the largest groups in Oka – moved to settle in Owalusin region; a majority of Idofin people exploited Ayegbunle as their new settlement, far away from the centre of Oka. Today, Ikanmu has kept its powerful position within Oka kingdom while Idofin's presence in community affairs has become much weaker. Thus, regardless of earlier migration trajectories in oral traditions, internal migration among quarters has made territory-based power relationships spatially twisted.

In sum, instead of taking a constructivist interpretation of changes and continuities of traditions, the framing of ‘twisted spatialities’ helps clarify how spatial relationships between the kingship and various actors and traditions are stretched or folded under the exercise of powers of reach. The establishment of the new palace stretches the space of symbolic powers. The accounts of yams and farmers illustrate that the representation of rituals is spatially centralized on the stage of Oka Day. The different practices and discourses of on-street masquerading demonstrate that spatialities of power are folded into the contentious politics over kingship and paramount authority. Recent migration in this region has redefined the scale of spatialities of powers in the oral traditions of Oka settlements.

The role of chiefs

Chiefs are major mediators of powers exercised by the king while also having agency to ‘make registers of powers quieter or muted’, according to Allen's (Reference Allen2011: 291) framing. In this case, the high chiefs of the fifteen quarters and other chiefs of sub-quarters should follow Oba Adeleye's instruction to represent and lead their people in Oka Day activities, but their involvements vary for various reasons. In printed Oka Day programmes, each quarter is supposed to advertise their blessings to the king and present images of representative high chiefs. According to the organizing committee, a full-page advertisement costs 20,000 naira (US$55 in 2018); a half-page is half that. By examining programmes from 2015 to 2018, we found that some quarters were highly visible (e.g. Ikanmu, Ibaka), some appeared intermittently (e.g. Korowa, Ebinrin), and some were never seen (e.g. Idofin, Owake, Ebo). In our interviews with high chiefs, some said that they decided to give up advertising in the programmes because ‘the price is too much’.

Although registering powers of reach from the king is partly muted by chiefs in the representations of the various quarters in Oka Day programmes, power effects of kingship are centralized and exercised over the chieftaincy institution during the events of Oka Day. In the setting of the Oka Day ceremony, people from the same quarters are instructed to sit together under labelled canopies while their high chiefs sit in the grandstand with the king. One of the common participatory activities is the parade led by each quarter's chiefs. They march in front of the king and greet him in a respectable manner (Figure 2). If elder chiefs are not able to walk around, younger chiefs can join dancing performances to represent their quarters. The majority of high chiefs usually attend this event and participate in the whole process, except Asin and Olusin.

Figure 2 Chiefs leading Ibaka quarter to greet Oba Adeleye.

In the organizational process of Oka Day, high chiefs in Oka-oka and Owalusin completely mute the registers of powers of reach exercised by the king and the organizing committee. As well as Asin, who has long-standing issues with Oba Adeleye, Olusin has recently challenged the king's authority. In an interview, he claimed that Owalusin people have their own New Yam festival every first Saturday of August on the same day as Oka Day. However, on 4 August 2018, we did not observe anything happening in Owalusin. One of the organizing committee members told us that Olusin used to attend Oka Day but later refused to go. Aro of Owake quarter, who had been mediating the relations between Olusin and the king, confirmed that this was because Olusin wanted to be the leader of Oka region, but Oba Adeleye did not accept this. In other words, Olusin attempted to exercise powers of reach over the whole of Oka, but his powers are discursively restricted to his territory in the context of Oka Day. His chiefs and people in Owalusin have their own agency to attend Oka Day. For instance, on 1 August 2018, many residents of Owalusin attended the healthcare services hosted by Okarufe Club in the Owalusin palace. Olusin's absence thus becomes a way of muting the registers of powers of reach.

Unlike earlier studies that focus on the ways in which kings’ powers interact with those of chiefs in the competitive politics over crowns and titles (Apter Reference Apter1992: 83–94), in contemporary Oka evidence shows that Oba Adeleye exercises limited powers of reach in chieftaincy politics. For instance, since 1965, the position of high chief in Iworin quarter has been vacant; two ruling families are still in dispute over this position. Given the vacancy, there have been no representative chiefs leading people to Oka Day activities. In the parade section, leaders of youth groups from Iworin take an active role, and Mr Arise was given an honorary chief title by Oba Adeleye to represent the quarter in some cases. When we asked why he had not appointed a high chief for the Iworin people, Oba Adeleye replied that he did not have the authority to do so: ‘It is their decision to elect their own high chief.’ The election of a high chief is time-consuming. The position of Asalu in Korowa quarter was vacant for ten years. In contrast, Olumogun of Isiri-Korowa was elected within eighteen months – the fastest election process in Oka. Olowase, the high chief of Owase quarter, commented: ‘Nobody wants to be a chief.’ Nevertheless, in many places, such as Iworin and even Oka, the competition for chieftaincy and kingship is extremely tense.

Vacancies for high chiefs affect the king's powers of reach in the quarters, especially in terms of Oka Day participation, because the kingship relies on chieftaincy to mediate powers of reach in the institution of Oka Day, although the organizing committee takes charge of coordination works. The deaths of high chiefs in quarters such as Agba (in 2018) led to a lack of participation, although other chiefs from Agba sub-quarters attended Oka Day. Due to close blood relationships with the king, chiefs in Ibaka quarter have had to be active mediators over the years.

In sum, this section echoes Apter's (Reference Apter1992) account of dialectics of power in chieftaincy and kingship politics by analysing how chiefs mediate the powers of reach in the institution of Oka Day. Instead of focusing on transformative actions in local politics, such as ‘manipulating, revising, or even breaking and remaking prescribed rules’ (ibid.: 73), this research identifies more nuanced power practices – quieting and muting registers of powers backed by chiefs towards the kingship and the organizing committee. Chieftaincy politics, in this sense, are widely and implicitly performed in the institution of Oka Day.

Beyond the locality

One of the new characteristics of the Oka Day celebration, compared with community day celebrations in the 1990s (Trager Reference Trager2001), is the increased involvement of actors beyond the locality of Oka. Previously, community days were mainly convened and organized by traditional authorities, including kings, chiefs and ad hoc committees (ibid.: 22–3). At the 2002 Sagamu Day, fundraising from local migrants became a primary part of the ceremony (Nolte Reference Nolte2009: 226–8). In this case, having guests outside Oka attend Oka Day is particularly significant. These newly emerged actors include politicians, wealthy businesspeople and established Oka natives from other states and abroad.

First, the involvement of politicians, especially Oka descendants, is crucial to the institution of Oka Day. When the format of Oka Day was gradually developed in recent years, high-status guests were carefully profiled by printing their names and images in the Oka Day programmes. Regular guests have included Ondo State governors, Senator Ajayi Boroffice, Mr Babatunde (a member of the House of Representatives in Abuja), Kazzem Suleiman (a member of Ondo State House of Assembly) and the chair of Akoko South-West Local Government. According to the organizing committee, the sequence of their appearance in the programmes reflected their political status. The image of Oba Adeleye always follows the images of Ondo State governors, and the local government chair is usually last.

The strategic representation of profiles in Oka Day programmes demonstrates powers of reach exercised by the organizing committee; however, registers of these powers were muted and challenged by some politicians. For instance, in 2017, the deputy speaker of the House of Representatives in Abuja, Yusuf, was introduced by Mr Babatunde to attend Oka Day. Yusuf claimed that his photograph should appear before those of Ondo State governors. However, the committee thought that this arrangement was not appropriate according to their understanding of the power hierarchy, so his image was placed after the governors and before the king. In the end, Yusuf did not show up on Oka Day.

Donations have been a material indicator of powers of reach. Since the 1990s, Oka Day has aimed to raise funds for building the new palace and for the development of Oka ‘community’. On Oka Days, the donation made by each person is announced over the loudspeakers to all audiences. This moment is usually a highlight of the ceremony and draws a great deal of attention. In 2018, a fifty-year-old male audience member told us that the reason he came from Ilaje – a town in Southern Ondo State – to attend Oka Day was because he wanted to confirm whether last year's donation had been spent well and if these politicians’ promises had been fulfilled. Senator Ajayi Boroffice's donation satisfied many of the audience members we interviewed in 2018. In contrast, Yusuf, the guest who contested the placing of his photograph, promised to donate two million naira in 2017, but people complained that he did not contribute anything.

The institutionalization of Oka Day helps attract politicians’ attention and participation, as they need to make material and monetary contributions in exchange for political support. The organizing committee told us that, in an election year, many politicians would want to attend Oka Day because they could advertise themselves through this popular event. It was widely observed from our participation during 2015–19 that politicians’ campaign advertisements were always hung up together with Oka Day posters. Among all the politicians, Senator Boroffice has been providing constant support for the development of his hometown, including facilitating the construction of the present palace and grandstand. In return, Oka has been his political base in pursuit of Ondo governorship in electoral politics. This electoral strategy was employed by politicians during 1979–83 at the time of the Second Republic of Nigeria (Vaughan Reference Vaughan2006: 155–93). The well-organized and institutionalized Oka Day attracts politicians in this regard. For the organizing committee and the king, this institution helps extend powers of reach beyond the locality of Oka to outside guests.

Second, on recent Oka Days, powers of reach to resourceful individuals have been exercised by endowing honorific ad hoc titles, including honorary chief, Okarufe Golden Merit award and the chair of Oka Day. Honorary chieftaincy is commonly noted in the colonial era as well as in democratic politics (Vaughan Reference Vaughan2006: 76–9). In Oka today, the king offers chiefs’ titles to those who are outside chieftaincy clans but have made significant contributions to Oka society. On 2015's Oka Day, a chief's title was conferred on Arogbofa as Asiwaju of Oka. Oba Adeleye held a brief ceremony for this vice-chancellor of Nasarawa State University. Similarly, the Okarufe Golden Merit award is usually given to Oka descendants who have made long-term contributions to Oka. In 2017, the award was offered to Chief Salami, who was one of the earliest organizers of Oka Day and who has brought resources of many kinds to Oka through his networks in Lagos. If the contribution is short-term, especially a large one-off donation (at least one million naira, according to the committee), the title of ‘chairman/chairwoman of Oka Day’ is offered. The chair is introduced formally at the beginning of Oka Day and invited to give a speech to audiences. The candidates for these ad hoc titles are recommended by the organizing committee and other reputable individuals in Oba Adeleye's networks, but confirmation is made by the king.

Third, to counter the effects of quarter chiefs quieting and muting registers of powers, social clubs and diasporic groups act as mediators of powers of reach; this has especially been the case in recent years when Oka Day has become much more formalized and publicized. Social associations have been active for a long time in African societies (Tostensen et al. Reference Tostensen, Tvedten and Vaa2001). These clubs are usually based on age groups and gender, such as youth, elderly men and women, and therefore differ from common social bonds on the basis of ethnicity and territory. In Oka, for instance, Amity Club was established in 1988 and the current president, Abubakar, is also the secretary of the organizing committee. He said, compared with the early years in the 1990s, active social club members play more significant roles in organizing Oka Day, especially with regard to sourcing funds and reaching out to potential guests. Additionally, since 2015, Okarufe Club, an elite social club composed of only ten upper-class members based in Lagos, has sponsored free healthcare services in different quarters in Oka. These social clubs exercise powers to connect local people who may attempt to disconnect from the institution of Oka Day.

Apart from social clubs, diasporic groups have recently become involved with Oka Day celebrations. For instance, Oka Descendants Union of North America is a registered non-profit organization based in Illinois, USA. They have held two international conventions to gather Oka diaspora: in 2015 in Canada and in 2018 in the USA. For their hometown, they donated computers to secondary schools in 2013 and co-sponsored the healthcare service with Okarufe Club in 2016. On Oka Day in 2017, the president of the Union, Adeyeni, attended and announced a donation of US$2,000. All these connections and contributions result not only from the willingness of diasporic groups but also from the king's powers of reach. Oba Adeleye has visited the UK and USA several times in the past decade in order to ‘find out and unite those Oka people abroad’, as he said. Besides Nolte's (Reference Nolte2009: 227–8) interpretation of community development festivals that affirm a town's place and meaning in the world, we have discovered evidence that the institution of Oka Day operates beyond the locality of Oka through diasporic connections in a globalizing world.

Conclusion

This article provides a case study of a Nigerian community day celebration acting as a constellation of power dynamics in which kingship, chieftaincy, local politics and global diaspora are intertwined. Instead of interpreting it in terms of either performative politics or community development, we treat the community day as an institution of powers. Indebted to geographies of powers, this article specifically focuses on spatialities of powers – the plural form of powers that are conceptualized and practised differentially by actors. Spatiality, as a key geographical term, signals the specific microphysics that are underexamined in previous African studies literature on kingship and chieftaincy. The analytical focus of spatiality helps us tease out the institutional mechanism of power dynamics.

After our inductive analysis of data collected over five years, we employ a framing of ‘powers of reach’ (Allen Reference Allen2011) to interpret spatialities of powers. Oka Day becomes an institution in which the king and the organizing committee exercise powers of reach in the quarters of Oka and beyond the town's locality. As a changing web of power relationships, the institution of Oka Day is associated with the king but also incorporates the king. Individuals, including chiefs, members of social groups, invited guests and ordinary audience members, can exercise powers and respond to effects of powers of reach on their own level while also being subject to interactions among those who exercise power. This relational approach to understanding Oka Day takes seriously the nuanced power practices on the ground, illustrated as twisted spatialities of powers in the contexts of architecture, rituals and oral history narratives.

This new framing of powers adds to existing interpretations of chieftaincy institutions and politics in Africa in two ways. First, it sheds light on subtle and strategic practices of chiefs faced with powers of reach exercised by the king and through the organizational institution of Oka Day. Although competitive politics over chieftaincy and kingship are still evident in Oka's history and reality, when it comes to Oka Day the tensions and differences of opinion are implicated in the performative politics of individual participation. This nuance manifests in the ways in which the registers of powers of reach are quieted and muted by some chiefs. Other chiefs become mediators of powers exercised by the king and via the newly established Oka Day institution he represents. Second, in addition to the intertwined relationship between local customary authorities – the king and chiefs – and all levels of politicians, this article also demonstrates how actors beyond the locality are drawn into the institution of Oka Day by powers of reach. In this sense, Oka Day becomes a power-laden arena in which the actors mentioned above pursue their goals in capital-driven activities. Some new actors, including social clubs and diasporic groups, have become more active in recent years; this deserves further exploration in the context of the global connections of Africa's chieftaincy politics.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to traditional rulers and other informants who made themselves available for our interviews and shared information and material with us. Our gratitude also extends to Henry Drewal, Matthew Turner and Robert Kaiser, who made comments and suggestions on the early versions of this article.