Introduction

In Ghana's general elections in 2008, the Ghana–Togo borders were closed by the New Patriotic Party (NPP) government, allegedly to prevent the Ewe people in Togo from crossing over to vote in Ghana's elections for its main opponent, the National Democratic Congress (NDC) party. The issue of ‘aliens’ – particularly Togolese Ewe – voting in Ghana's presidential and parliamentary elections has been a cause of electoral conflict since the return to multiparty democracy in 1992. In 2015, three years after losing the 2012 general elections to the NDC, the NPP alleged (with regard to the voters’ register used in the 2012 general elections) that ‘using facial biometric recognition technology, the system has found 76,286 potential matches of the same people, with the same names and faces on the Ghanaian as well as Togolese voters registers’.Footnote 1

Such contestations over cross-border voters point to a key source of tension: between citizenship within territorially bounded nation states and ethnic citizenship of local, culturally demarcated communities. National citizenship, which is promoted by states as a central component in building the nation state, comes into conflict with a sense of belonging to a culturally demarcated local community whose inclination is to prioritize the interests or reproduction of the group. This reality of political organization of borderland communities in contemporary Africa has significant implications across the continent. The case has comparative value, as the bisection of ethnic communities across state boundaries is a feature of practically all African states.Footnote 2 Along Ghana–Togo shared borders, we see the problems through cross-border participation in elections; in other cases, such as that of Kenya, we witness political violence and instability.

Many of these tensions relate to the imposition of borders by colonial authorities. In 1961, Togbe Abledu Aklama II, the self-styled chief of Nyive-Ghana (British Nyive), wrote a protest letter to the Regional Commissioner contesting the government's recognition of Doamekpor as the chief of Nyive-Ghana.Footnote 3 He asked:

[I]s it to be understood that, as from now, any member of the stranger community of a town or a division could be declared as the paramount head over and above the natives? Or is it to be understood that Ghana Nyive by virtue of the fact that the owners are our brothers in the Republic of Togo … has become no man's land, even if some of the relatives who are entitled to ownership as well do reside in Ghana?Footnote 4

Togbe Abledu Aklama II argued that he, Togbe Aklama II, owed his position as chief of Nyive-Ghana to his relationship as the nephew of the chief of Nyive-Togo, whom he claimed was the overlord of both Nyive-Ghana and Nyive-Togo. His protest is but one example of many in which notions of political space on the Ghana–Togo boundary were contested.

The Ewe were not exceptional in finding discrepancies between their ideas of political space and those of the colonial and postcolonial states. On the Nigeria–Cameroon border, the Mandara, separated by the international boundary, still held on to their traditional allegiances. Those in Nigeria deemed chiefly titles legitimate only if they were bestowed by the Sultan of Mandara, who was located in Cameroon (Barkindo Bawuro Reference Barkindo Bawuro and Asiwaju1984). Similar discrepancies abound between local people's ideas of political space and those upheld by the British policies of indirect rule, which required a neat overlap between authority over people and authority over land (Cormack Reference Cormack2016). In well-established, centralized territorial chieftaincies, ‘stranger’ communities created problems (see Berry Reference Berry2001; Austin Reference Austin2005; Schildkrout Reference Schildkrout2007; Parker Reference Parker2000). Discrepancies were particularly evident in the case of ‘acephalous’ or ‘decentralized’ states (Lentz Reference Lentz2006; Allman and Parker Reference Allman and Parker2005). What is interesting about the Ewe case, however, is that it does not correspond to either of the main categories that are typically deployed by historians and anthropologists. Ewe speakers did not form a large-scale centralized state, but nor were they ‘acephalous’; chieftaincy was practised in the precolonial era, but on a very small scale. This is what made the Ewe so problematic for their colonizers as they tried to redefine local political space and authority. This article explores how chieftaincy emerged and evolved in relation to other forms of organization such as citizenship and ritual understandings of space in two Ewe-speaking communities, Nyive and Edzi. These communities were bisected by the Ghana–Togo boundary in the aftermath of World War One, when the British and French split the former German colony of Togo between themselves and established new administrations under international oversight (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Ghana–Togo boundary showing Nyive and Ave-Dzalele/Edzi.

Giulia Casentini argues that the ‘concept of space in sub-Saharan Africa has been shaped in distinct and lasting ways by the international and internal political boundaries that the European colonial powers defined’ (Casentini Reference Casentini2014: 177). Most studies of pan-ethnicity, in which kin-related groups increasingly identify as members of a larger group, suggest that this often occurs in response to incorporation into larger political units (such as colonial states), which results in competition for power and resources. Studies that emphasize politics suggest that splitting the Ewe into two states, and hence reconfiguring Ewe political space, would have weakened pan-ethnic identity. For instance, Benjamin Lawrance notes that ‘many Ewe may have regarded the establishment of British and German colonial administrations, which to a considerable degree further fragmented Ewe political divisions, as central to their conception of “self” and of “collective” political and social units’ (Lawrance Reference Lawrance2007: 34). This article demonstrates, on the contrary, that the Ewe deployed ritual space to ensure or support pan-ethnic solidarity across state boundaries. A sense of belonging to a distinct community was transformed and reinvigorated through cultural practices such as rituals within the institution of chieftaincy. These sustained a sense of belonging to an Ewe community that straddled the international boundary. In other words, shared cultural traditions became anchors of a shared identity, some of the performance of which was tied to spaces that cut across such borders.

This article stresses the need for an analytical distinction between political and ritual authority, since the evidence suggests that the latter can be maintained even in the absence of the former. It argues that relationships have changed, from those concerned with political hegemony to largely ritual practices. Although distinct, both are co-determining: the salience or legitimacy of political authority is sustained by ritual authority, and chiefly authorities invest in these rituals to maintain political authority. Shared ritual practices are thus mobilized to promote a sense of belonging among Ewe communities that straddle state boundaries. This is evident in the phenomenon of ‘international chiefs’ expressed in continued allegiances of village chiefs in Ghana to senior or paramount chiefs in Togo.

In order to grasp the importance of these rituals of authority within Ghana, it is necessary to recognize the significance of chieftaincy in Ghana and in the sub-region. Prior to colonial rule, it was merely one of several forms of political organization. However, as a result of it being privileged under the British colonial system of indirect rule, it started to be perceived as pre-eminent, and it dominated over other forms of precolonial political organization. Postcolonial governments in Ghana have maintained this status by recognizing and privileging the chieftaincy institution (see the 1992 Constitution of Ghana). Thus migration histories have been interlaced with the chieftaincy institution, particularly the possession of a stool to indicate the antiquity of the institution among these communities. Among ethnic groups such as the Ewe, stools are particularly significant – not only as political symbols but also in legitimating chiefs. The stool is the symbol of authority of the chief, who is said to be ‘enstooled’ when installed in office (or ‘destooled’ when removed from it), and who assumes a ‘stool name’ as part of the ceremony. As part of the enstoolment rites, in which the zikpuitor (owner or custodian of the stool) plays an important part, chiefs are placed ceremoniously on the stool.

The article is divided into three sections. The first describes the situation in the present day, highlighting the centrality of chieftaincy rituals in the reproduction of transborder ethnic communities. The second examines the ways in which the colonial authorities laid the foundations for the situation today by looking at the incorporation of Nyive and Edzi into the British colonial sphere and at how this affected the chieftaincy institution in these bisected Ewe communities. The third discusses the origin, migration and settlement of these two groups and their precolonial political organization – particularly the emergence of chieftaincy in relation to other forms of organization of people and understandings of space, with special reference to the ritual sphere.

‘International chiefs’

The reconfigured territorial scale of political organization under colonial rule did not destabilize cultural traditions that are shared by Ewe. Rather, cultural performances – including the officiants, ritual objects and oaths used in enstoolment, and burial rites associated with the chieftaincy – sustain a sense of belonging to a culturally distinct Ewe ethnic community in relation to other ethnic formations.

It is important to note, however, that Ewe struggles to maintain cultural interaction involve negotiating tense relations with the state, whose officials do not take kindly to practices that disregard or offend national citizenship or cast doubt on Ewe loyalty to the national project that they embody. The Ewe have developed what David Brown calls a ‘reputation as a politically active and ambitious community’. He notes that ‘it is the particular influence of the territorial boundaries across Eweland which makes the identity problem of the Ewes so politically salient’ (Brown Reference Brown1980: 579).

This reputation stems largely from, and dates back to, their vociferous opposition to their partition by the international boundary. Agitation for the reunification of the Ewe by the All Ewe Conference in British Togoland and the Gold Coast and the Comité de l'Unité Togolaise (CUT) in French Togo compelled the United Nations to investigate the ‘Ewe problem’ to see how this could be resolved. The first visiting mission to the Trust Territories of British Togoland and French Togo was directed to ‘give attention … to the Ewe problem in Togoland under French and Togoland under British administration’ (UN 1951: 1). The instruction to give attention to the Ewe problem was contained in the ‘Special report on the Ewe problem’ (ibid.). Ewe campaigns for unification did not end with the plebiscite in British Togoland in 1956, which culminated in the area becoming part of the Gold Coast (Ghana). On the eve of Ghana's independence in 1957, some groups opposed to integration staged attacks in Alavanyo in the Volta region of Ghana.Footnote 5

Members of the communities bisected by the international boundary have been harassed by both Togolese and Ghanaian security officials at the border post, especially in relation to funerary practices. According to Togbe Dunyo Hodzi IV, chief of Ave-Atanve in Ghana, until the 1980s, when a cemetery was established in Ave-Atanve, people were subjected to corporal punishment by Togolese officials if they failed to notify these officials that they were bringing a corpse to bury in Edzi in Togo. Ewe custom has it that people ought to be buried in ancestral homes, and one effect of the border dissection, in the case of Ave-Atanve and Edzi, is that the location of these homes and burial grounds falls on the other side of the international boundary. After taking a corpse to Edzi, a family was compelled to report to the Togolese officials, who were stationed about 15 kilometres from Edzi, before they could return to Edzi to perform the burial.

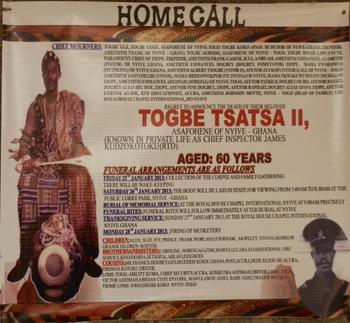

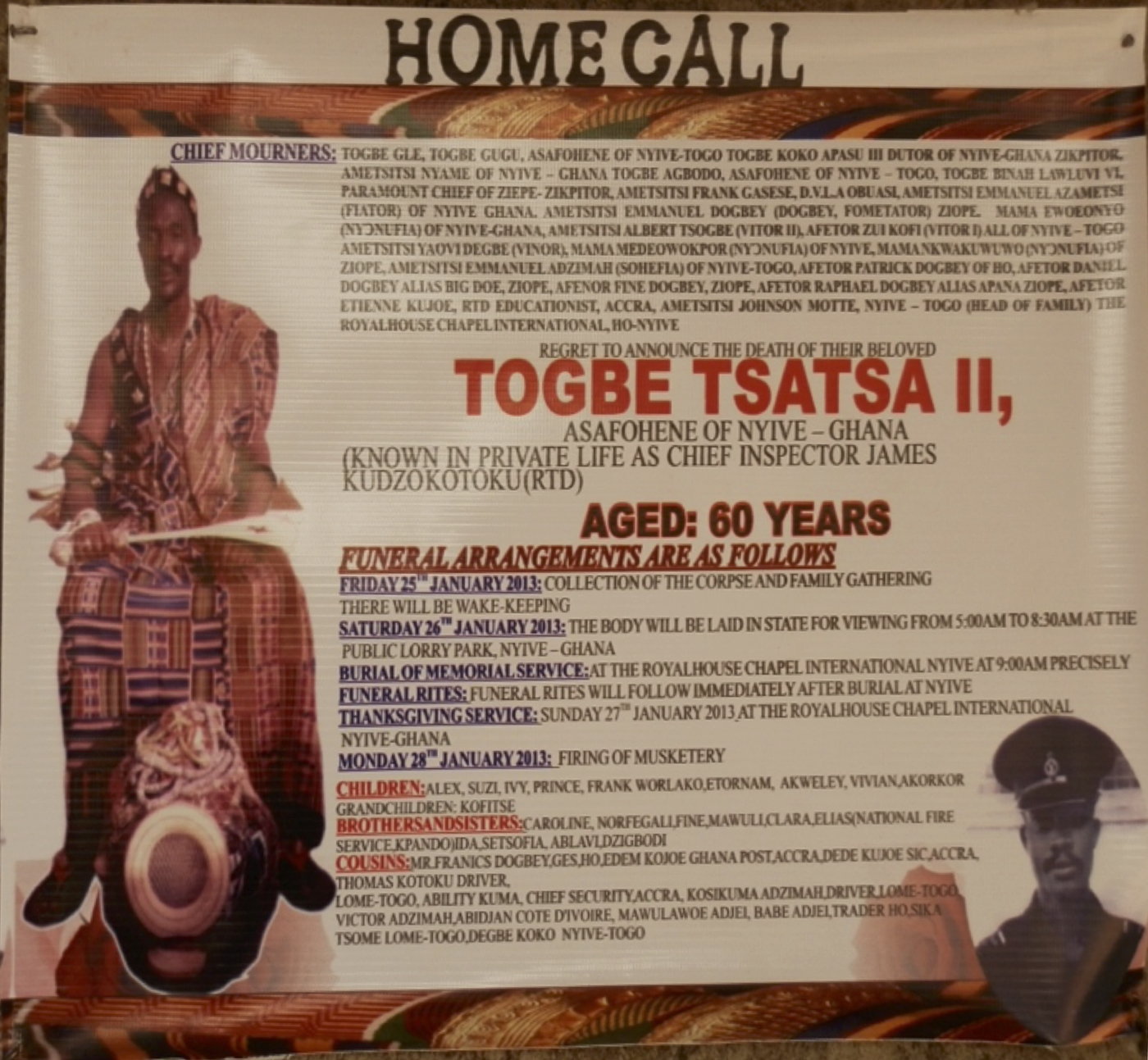

The harassment of the Ewe notwithstanding, these transborder ethnic communities continue to reproduce their collective identities across borders through investment in cultural rituals and practices. The continuity in practices, despite the restrictions imposed by the international boundary, is recast within cultural spaces to ensure the sustenance of an Ewe ethnic identity. Further evidence of the way in which this happens through funerals can be found in funeral posters. In Ghana and parts of contemporary West Africa, these are a well-entrenched part of funerals (see Figure 2). Couched as a ‘call’ to others from the same home, and made available to community members on either side of the border, they provide socially significant details of the deceased's life: date of birth, professional accomplishments, details of immediate family survivors that amplify the deceased's achievements in life, their standing within various social and political hierarchies, and so on. Their use shows the dynamism of the nature of the relationship between bisected communities.

Figure 2 Funeral poster of the late Togbe Tsatsa II, asafohene of Ghana Nyive.6Footnote 6

The ‘chief mourners’ announced at the top of the poster – usually clan heads, lineage heads and family heads – are the most important people in the deceased's family, village or work and are the principal overseers of the funeral. They also include the deceased's most important superiors at work, the principal chiefs of the village, if the deceased is a chief, and – if he or she is a national figure – the head of state. The list of chief mourners is arranged hierarchically, with the name of the most important person or superior authority appearing first.

The funeral poster of the late Togbe Tsatsa II of Ghana Nyive (Figure 2) reveals the nature of the relationship between the Nyive-Ghana and Nyive-Togo stools. It shows the subordinate relationship of the Nyive-Ghana chief to that of Nyive-Togo in the hierarchy of chiefs within the political structure of the two communities. Both communities are still regarded by the people as one, with Nyive-Togo and Nyive-Ghana referred to as gbↄhohome (old town) and gbↄyeyeme (new town) respectively, even though some people take exception to even the notion of such a division between Nyive.Footnote 7 Nyive-Togo is the traditional seat of both Nyives and the chiefs and elders there are considered to be senior to those of Nyive-Ghana. Thus, hierarchically, Togbe Gle, the acting head of Nyive-Togo, is the overall head of both towns. Togbe Gugu VII, who is the asafohene (chief of the warriors) of Togo Nyive, is overall commander of Nyive warriors.

As depicted on the funeral poster, the first of the ‘chief mourners’ was Togbe Gle, who then acted as the chief of Nyive-Togo and as such was paramount chief of both Nyive-Togo and Nyive-Ghana. He is followed in the list by Togbe Gugu VII, who is the asafohene of Nyive-Togo and thus Togbe Tsatsa's superior commander. Next in the list is Togbe Apasu III, mankralo (owner of the town) of Nyive-Ghana, and then acting as the paramount chief of Nyive-Ghana. So even though Togbe Tsatsa was Togbe Apasu's subordinate chief, his name appears in the list of ‘chief mourners’ after the chiefs in Nyive-Togo. This is a manifestation of shared cultural rites showing marked forms and order of authority in specific domains in the two towns.

The funeral rites themselves are equally important in the reproduction and reconfiguration of Ewe collective identity. The adaptation of Akan-type military formations of rear, advance, left and right wing, with chiefs in charge of each wing, has had an impact on the relationship between political space and cultural space, reinforcing a sense of collective identity as a response to – and outcome of – incorporation into the colonial state.

On the fifth day of the funeral rites, Togbe Gugu led the asafowo (warriors) of Nyive-Ghana and Nyive-Togo at the funeral of Togbe Tsatsa. Togbe Gugu welcomed the asafowo to the funeral grounds in Nyive-Ghana. Carrying his sword and human skull, he performed traditional warrior dances ahead of the asafowo of both Nyive-Ghana and Nyive-Togo. This stemmed from his position as the leader of all the asafowo in both Nyive-Ghana and Nyive-Togo. Importantly, as Togbe Gugu explained, Togbe Tsatsa was his subordinate chief who occupied the ‘left wing’ in combined Nyive military formation.Footnote 8

There is similar cross-border joint participation in rituals among the people of Ave-Dzalele in Ghana and Edzi in Togo; these rituals are performed by ‘international’ chiefs whose authority is recognized as transcending the international boundary. Among the Edzi it is the Adefo, the dutor (landlord) of Edzi in Togo, who performs the enstoolment rites for all the chiefs of the Ave-Dzalele traditional area in Ghana. The Adefo, as the custodian of the land, is customarily designated to enstool all Edzi chiefs in both Ghana and Togo, and the legitimacy of these chiefs depends on his having enstooled them. One of the enstoolment rites involves dipping the feet of the chief in the blood of a ram, as occurred during the enstoolment of Togbe Hodzi IV as chief of Ave-Atanve in Ghana (Figure 3).Footnote 9

Figure 3 Togbe Adefo of Edzi in Togo dipping the feet of Togbe Hodzi IV in the blood of a ram as part of his enstoolment as fia of Ave-Atanve in Ghana. Source: Togbe Hodzi IV, fia of Ave-Atanve.

An important ritual object in the performance of funerals for chiefs is the drum. Drums are significant in traditional rites more generally; they are used to provide the rhythm for dances during which messages are communicated that express the history of the people. Most importantly, the spiritual presence and protection of the ancestors are invoked by playing the drums.

In the Nyive pantheon of drums, adavatram, abento and konfodi are ranked in that order of seniority. The adavatram (‘madness has overtaken me’) is no ordinary drum. It has seven human skulls tied around it and human elbow bones are used to play it. The adavatram is played only seven times and no ordinary person can dance to it. Only chiefs, elders and great warriors, or those possessed by the ancestral spirits, may dance to its music. It is usually played at midnight, and before it is played strangers are warned to stay away from the proceedings. It is used in the performance of rites such as the funerals of high-ranking chiefs such as the fiaga (paramount chief), mankralo, asafohene and other elders.Footnote 10

Togbe Tsatsa II was one such official whose funeral demanded the use of the adavatram. Like most of the ritual objects of the Nyive, this drum is located in Togo-Nyive. However, there are prohibitions against it crossing a river, and, given that the Wutↄ separates the two communities, it was impossible for it to be brought to Nyive-Ghana.Footnote 11 In its place, the abento drum (see Figure 4), the ‘mother’ of the adavatram, was brought to perform the rites and played the beats normally reserved for the adavatram. The beats communicate messages such as Εdzro gidi, aƒetↄ gidi Εdzrotↄ a kplↄ εdokoe vε (‘The bad stranger will reveal himself’). As with the other important drums, before the abento is played certain rituals have to be performed. Togbe Gugu, the asafohene, performed the rituals for the drum and the carrier before the abento was sent to Nyive-Ghana. On the final day of the nine-day funeral rites, the abento was the main ritual object.

Figure 4 The drum carrier from Nyive-Togo carrying the abento drum during the funeral rites of Togbe Tsatsa II at Nyive-Ghana, 2 February 2013.

It is believed by the Nyive that when these rituals are performed for the drums, the ancestral spirits come to join in the activities. The presence of these spirits is visible in the actions of the carrier of the drum. At one point in the proceedings, there was a commotion when the elders wanted to take the drum from the carrier. He refused to let go and it had to be forcibly taken from him; herbal concoctions were sprinkled on him to calm him down. For fear that he might do something untoward if left by himself in that state, he was also held down until he was calmer. His behaviour, according to the elders, was due to the fact that he had been possessed by the ancestral spirits who had been invoked and invited to be part of the ceremony by the playing of the abento. In such cases, ritual objects serve as important mediums in the reconstruction of Ewe collective identities, by literally calling up the common ancestors of those who might otherwise be divided.

Another important aspect of the relationship between the bisected communities is evident in the swearing of oaths (atabu). Oaths highlight the reproduction of chiefly relations following the imposition of the international boundary, as some of the chiefs who swear the oath or respond to it reside on the opposite side. Oaths within the chieftaincy institution are sworn during the enstoolment of chiefs and at their burial to show allegiance between chiefs as well as between chiefs and their subjects.Footnote 12 A subject can also take a chief's oath to prove his innocence or to bring a case before the chief. The atabu places a responsibility on the person who says it and on the respondent. The swearer declares that if he did or does something forbidden, or reneges on his responsibilities, then he has broken the oath. In the case of Togbe Tsatsa's funeral, Togbe Gugu, as the dead man's superior, swore the oath to Togbe Tsatsa's fiatↄ (father of the chief) and the mankralo of Nyive-Ghana. He said that if, as his superior officer, he had known what killed Togbe Tsatsa and had not prevented his death, then he would have acknowledged breaking Nyive's great oath.

The examples above tell us something about how the status of elders in satellite communities has evolved vis-à-vis that of chiefs in the legal jurisdiction of the neighbouring state of Togo. Politically, the direct authority of the chiefs of the bisected communities is absent in the day-to-day activities of those living in Ghana, but the chiefs still wield some authority in the ritual sphere. Thus, Ewe cultural space – particularly relating to rituals shared by lineages scattered widely across geographical regions – has sustained a sense of belonging to a culturally distinct community. This might otherwise have been under stress as a result of colonial political boundaries and the local institutionalization of the colonial state and its counterparts in the postcolonial state. It is in the ritual sphere that the ‘international’ aspect of the chieftaincy was performed, and in the ritual sphere that the chieftaincy transcended the international boundary.

In the next section I explore how the colonial authorities laid the foundations for this state of affairs.

Colonial partition and administration

The European acquisition of Ewe territories and the imposition of colonial boundaries took different forms and occurred at different stages. By 1886, Eweland – which stretched from beyond the River Mono in the east to the River Volta in the west, or roughly the south-eastern part of Ghana and the southern part of Togo and south-western part of Benin – had been divided among Britain, Germany and France in their colonies of the Gold Coast (Ghana), Togo and French Dahomey (Benin) respectively.

Nyive and Edzi were part of the German protectorate of Togo. Following the outbreak of World War One, when German Togo was occupied by British and French troops and temporarily divided between the two powers, both Nyive and Edzi came under the British sphere of influence. In 1919, the two polities were split under the Anglo-French boundary agreement. For Nyive, the River Wutↄ was set as the boundary between the British and the French (Bening Reference Bening1983: 200). The Anglo-French boundary also severed the Edzi towns that now make up the Ave-Dzalele traditional area in Ghana from the parent polity in Togo.Footnote 13

Nyive and Edzi, as part of British and French Togolands, were administered as League of Nations mandated territories and later as United Nations Trust Territories after World War Two. Colonial policy reorganized chiefly authority and, under the British policy of indirect rule, the chiefs maintained some semblance of authority while in reality they were controlled by British colonial officials. On assuming jurisdiction of the Trust Territory, the British felt that, for effective local administration, the proliferation of traditional states ought to be grouped together into larger units. According to the British authorities, there were too many of these states. They therefore merged independent traditional areas under a ‘paramount chief’ within what were known as ‘amalgamated’ states.

The policy primarily grouped about sixty-eight independent traditional polities (otherwise referred to as divisions) in the southern section of British Togoland into larger states of manageable size and population for convenient administration. These amalgamated states with state councils and headed by a paramount chief became the organs of local administration. They could pass their own by-laws; however, they were under the supervision of the colonial administrators. The amalgamated states created were Asogli, Akpini, Avatime and Buem (Nugent Reference Nugent2002: 127). Both Ave-Dzalele and Nyive-Ghana were part of the Asogli state.

The British colonial policy of indirect rule was meant to bring these bisected polities fully within the British colonial sphere. That is why, in the Nyive-Ghana chieftaincy dispute referred to earlier, the colonial officials claimed that Nyive-Ghana was an independent division and owed no allegiance to the chief of Nyive-Togo. The District Administrative Officer at Ho in the Gold Coast, in a letter dated 11 October 1956 to the Regional Administrative Officer on the question of chieftaincy in some Ewe dukↄwo (states) divided by the Ghana–Togo boundary, stated: ‘The Ghana–Togo boundary precludes the people of Edji living in Ghana from any political allegiance to the Paramount Chief of Edji in Togo. The same applies to Nyive.’Footnote 14

In Ave-Dzalele, oral histories dispute the British colonial records that one Kofi Dogli was ‘chief’ of Ave-Dzalele, although he addressed himself as such and was recognized by the colonial authorities in that capacity. According to Togbe Dogli II, paramount chief of Ave-Dzalele traditional area, Kofi Dogli only acted as a chief, as no customary rites were performed to enstool him as one.Footnote 15 He was a ga (elder) and a linguist to the Togbe Ake of Edzi in Togo. This was corroborated by other chiefs and elders in the Ave-Dzalele traditional area in Ghana and Edzi in Togo.Footnote 16

While the British authorities might have recognized Kofi Dogli as a chief, the Edzi people did not. This probably explains why the chief of Ave-Dzalele was always accompanied by the chief of Edzi in Togo to meetings in British Togoland; this point was made by Captain C. C. Lilley in his notes on amalgamation. One ought to add that, in Lilley's report, the title ‘chief’ is in quotation marks, probably in recognition of the fact that he was not customarily recognized as occupying such a position.Footnote 17 But how did chieftaincy emerge and evolve in relationship with other forms of organization of people, such as clan and lineage, in the bisected communities, and how did other understandings of space develop – particularly in the ritual sphere?

Origins, settlement and political organization

Nyive and Edzi oral traditions speak of some kind of migration to – rather than an autochthonous development in – their present location. According to the oral traditions, by the fifteenth century the Ewe had settled in Notsie (in Togo), the reputed cradle of the Ewe before their final dispersal to their present locations because of the cruelty of their king Togbe Agorkoli. The migration from Notsie was not one mass movement but a series of smaller ones: the Ewe moved in three groups that settled between the River Volta to the west and the Mono River to the east. The Nyive migrated from Notsie with other groups including the Ho, Adaklu and Ave in Ghana and Gbalanvi and Taviefe in the Republic of Togo. The Edzi migrated together with the Ewe group that moved southwards in the seventeenth century. This included the Anlo, Some, Aflao, Agave and Mafi.Footnote 18

There is a debate over the question of chieftaincy in these movements. Did the Ewe settle in their present locations with their chiefs or did the chieftaincy institution evolve after they had arrived? Kodzo Gavua notes that the traditional leadership position was headed by the chief custodian of the land, aʄetↄfia or ganua, who was assisted by the trↄfia (chief priest) of important deities. He attributes the present chieftaincy institution, involving the initiation of a ‘black stool’, to an Akan import (Gavua Reference Gavua and Gavua2000: 11–12). D. E. K. Amenumey, on the other hand, argues that contacts in Ketu with the Yoruba, who had chiefs, would have exposed the Ewe to the chieftaincy institution before their settlement in their present locations. In any case, the Ewe, he points out, were already familiar with the institution in the areas – Notsie and Tado – from which they migrated. The migrants were led by chiefs who fled Notsie, after which other chiefs later emerged as the original ‘founders’ of the villages. He thus asserts that what happened was an adaptation and modification of the chieftaincy institution over the years due to contact with the Akwamu (an Akan ethnic group) (Amenumey Reference Amenumey1986: 14). Michel Verdon argues that, among precolonial (particularly northern) Ewe polities, it was villages rather than small chiefdoms under paramount rule that were the sovereign political groups (Verdon Reference Verdon1980: 281). He further asserts that the ‘very label chief to translate fia is thus highly questionable in the case of Abutia and possibly all Ewe-dom’ (ibid.: 289).

Among the Nyive, there is no consensus on who led them to their present location, which they named Nyive, meaning ‘elephant forest’ (nyi: elephant; ave: forest), because of the elephants in the forest where they settled. According to Togbe Gle, regent of Nyive-Togo, the Nyive were led from Notsie by their chief Togbe Gle, his asafohene Gugu, and other warriors including Aganu and Agboro.Footnote 19 Togbe Gugu, the asafohene of Nyive-Togo, however, questions this. Although Togbe Gle was then chief, he maintains, it was Togbe Gugu who led them, as in those days they did not have a dufia (chief of a town) as they do now.Footnote 20 Togbe Apasu, the mankralo of Nyive-Ghana, on the other hand, claims that the Nyive left Notsie under the leadership of Togbe Apasu, their chief, who was assisted by other war chiefs including one Edior, who was later succeeded by his son Gugu.Footnote 21

Togbe Apasu's account is probably the most accurate, considering that among the Ewe the position of mankralo, also known as dutↄ or afetor (owner of the town), is reserved for the ‘founder’ of the town, a position he still holds. A chief of the town, however, could be selected from any group. In Mepe, for instance, the Gbanvie clan produces the paramount chief, although the Adzigo and Dzagbaku clans are said to have discovered the land. These two clans own the land but the Dzagbaku produces the mankralo. The mankralo’s ownership of the land is the basis for him performing the enstoolment rites (Dzobo Reference Dzobo2001: 13).

The Edzi consist of the Duvewo, the first settlers, and the Avedowo, who joined them after they had settled in Edzi. The Avedo are a Tongu-Ewe people who had settled with their kin in Mafi. However, due to wars with the Akwamu (an Akan ethnic group), they left Mafi with their stool and settled among the Edzi, with whom they were acquainted, having moved together with them from Notsie. They were offered a place by the Duvewo. They got their name Avedowo among the Edzi because they were asked to pass through the forest to the place they had been allocated. ‘Avedo’ comes from the statement ‘to avedo na do go’ (pass through the forest to go out).

The Avedowo, according to Togbe Kwame Dogli II, paramount chief of Ave-Dzalele traditional area, were under their chief Togbe Ake, who was an asafohene to Togbe Ahiatroga, the paramount chief of Edzi. The chiefship he claimed belonged to the Dzeke, one of the clans in Edzi. It passed to the Ahiatroga because, when the Germans arrived in the town, the people fled to their farms. Ahiatroga, a visitor from Dzadzafe who was lodging with the Dzeke, was at home and he was given the German symbols of office for a chief – flag and hat – to be given to the chief when he returned. Ahiatroga refused to surrender the items when his hosts arrived.Footnote 22

The origin of the asafo among the Ewe, some scholars have argued, is Akan.Footnote 23 The asafo among the Akan are ‘localised patrilineal military bands which perform both war-time and peace-time functions’ (Baku Reference Baku1998: 23). In Nyive, what comes close to the asafo is the sohewo (youth), which fits J. C. de Graft Johnson's narrow definition of asafo as ‘the young men of a town or state’ (quoted in Baku Reference Baku1998: 25). However, the sohe is not based on patriliny but made up of all the youth, both indigenes and strangers. The leader is the sohefia and could be chosen from the strangers’ group. The present sohefia of Nyive-Ghana is one such example. His parents came from Adaklu and settled in Nyive-Ghana. The leadership quality looked for in the sohefia is his ability to mobilize the youth for development projects. Traditionally, he is not a chief but he is very important in the governance of the state because of his influence over the youth.

The Nyive note that the position of the asafohene has existed since their migration from Notsie and all the various versions of their oral traditions name one Togbe Gugu as the asafohene. In Nyive, the titles avafia and asafohene are used interchangeably. There are other titles such as asafo and asafohe that are military ranks below the asafohene, and the stool names in their migration narratives are those of Togbe Gugu's lieutenants.Footnote 24 It is reasonable to conclude that this position might have existed before they settled in their present location. It is possible that there was a change in the name avafia following contact with Akan states such as Akwamu and Asante.

The Ewe also adopted limited degrees of centralized political organization. It has been argued that the tyrannical rule of King Agorkoli in Notsie accounts for this. It also seems likely that the pattern of intermittent migration, with groups spread across relatively wide areas, might be responsible for the reproduction of lineage-based and thus less politically centralized polities. Nyive and Edzi had chiefs, but both Nyive-Ghana and Ave-Dzalele (which developed as kↄfewo (villages) and agbletawo (farmsteads) of the parent state in Togo) did not. Instead, they had elders appointed by the chief to administer these settlements. In Edzi, gawo (elders) were appointed as heads of the new settlements such as Ave-Dzalele and Ave-Atanve. In the Nyive settlements across the Wutↄ, such as Dzↄkpe and Tsikpe, ametsitsiwo (elders) were likewise appointed by the chief to be in charge of these communities. While these were not autonomous, for all practical purposes they were independent. Oral histories in both Nyive-Ghana and Ave-Dzalele traditional areas, however, indicate that until the 1960s there were no chiefs in these two areas.Footnote 25

Rituals underscored relations among these related kinship groups. For instance, the Nyive-Ghana chieftaincy was structured along the lines of that of Nyive-Togo, with the stool names highlighting the nature of the relationship between them. In Nyive-Togo, the fiaga stool is Gle and in Nyive-Ghana it is Aklama; Aklama was Gle's grandson. The asafohene stool in Nyive-Togo is Aganu and its counterpart in Nyive-Ghana is Dordor; Dordor was Aganu's son. Similar relationships also exist between the other stools (Table 1).

Table 1 Relationship between stools in Nyive-Ghana and Nyive-Togo

All in all, the evidence from Nyive and Edzi thus suggests that the Ewe were familiar with the institution of chieftaincy prior to their settlement in their present locations. Ewe political organization, however, was pretty much decentralized. It seems that effective political power rested on lineages, although ritual power resided in or was mediated by chiefs or priests who did not necessarily hail from those same lineages. At some point, most likely in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and for reasons that included wars with their neighbours and with Akan states such as Akwamu and Asante, the Ewe polities experienced political change by borrowing some aspects of the chieftaincy institution and chiefly titles from the Akan, as Gavua suggests (Reference Gavua and Gavua2000: 11–12).

The stool, which is the most important chieftaincy regalia, is periodically cleansed by the priests in Togo-Nyive to appease the ancestors or seek their favour. The priests and elders are custodians of the stools, and, as such, they enstool their occupants. As Togbe Apasu pointed out with regard to the involvement of the people of Nyive-Togo in his enstoolment as mankralo of Nyive-Ghana in 1986, ‘those who perform the rituals are there’.Footnote 26

The idea of the legitimacy of a chief further sheds light on the relationship between political and social space, particularly in the spiritual sphere. The legitimacy of the chief rests on his being properly enstooled. As William E. Connolly points out, legitimacy is key to political authority seeking ‘the allegiance of its members’ (quoted in Ray Reference Ray1996: 183). Kenneth Baynes also notes that legitimacy is ‘a political order's worthiness to be recognized’ (quoted in ibid.: 183). Such bases of legitimacy, as they point out, could be secular or religious.

The religious basis of that legitimacy is important among the Ewe. Ray's assertion that ‘the custom of traditional authority in Ghana depends on the sacred’ (Ray Reference Ray1996: 184) applies to the Ewe. He explains that the ‘sacralization strategy of legitimation is implemented from the moment of inauguration of the new officeholder to that abdication, removal or death’ (ibid.: 184). ‘Custom is touched by divine purpose,’ says William Connolly, ‘and political authority is anchored in a larger cosmic order’ (quoted in ibid.: 184). Among the Ewe, without special ritual objects and their use by the designated people at the right time and in the right place, the office holders cannot be said to have been legitimately invested with the power not only to lead mortal men and women but also to commune with the ancestors who watch over the lives of the living. Thus, the role of these officiants and the ritual objects are crucial to the legitimacy of the occupant of the stool. This reinforces the ritual underpinnings of the political relationship between the partitioned communities.

Conclusion

An important feature of Africa's international boundaries is how they cut across ethnic groups, communities and families. The case of elections and cross-border voters in Ghana, with which this article began, points to tensions between national citizenship promoted by states and local/ethnic identities in culturally demarcated spaces. As the article shows, this was the case with some Ewe communities, which were bisected by Anglo-German and later Anglo-French boundary agreements creating the Ghana–Togo boundary. The policies of both colonial and postcolonial governments attempted to reinforce the separateness of the bisected polities. However, in Nyive and Edzi, two Ewe communities that sit astride the Ghana–Togo boundary, that boundary has not prevented chiefs from performing recognized ritual chiefly functions across the border, thus describing themselves as ‘international chiefs’.

This study highlights how rituals transform the construction of political space. With the establishment of the international boundary and colonial rule, relationships have changed specifically from political hegemony to largely ritual practices, as those elders on the Ghana side became chiefs. Older beliefs embedded in rituals that ensured allegiance to stools have been transformed to maintain relationships with communities that would otherwise have been divided by national citizenship. Shared cultural traditions have become anchors of belonging to culturally distinct communities, some of whose performance is tied to spaces that straddle the border. Relations have been reinvigorated through cultural practices and rituals that sustain a sense of belonging to a Ewe nation. Ironically, the fact that boundaries are conceived not only as lines drawn by the colonial and postcolonial state but also involve ritual authority that transcends them is sometimes recognized by the state and utilized in conflict resolution. For instance, in the chieftaincy dispute involving Ave-Dzalele and Ave-Atanve in Ghana in 2007, the intervention of Togbe Ahiatroga of Edzi in Togo, their traditional overlord, was sought in resolving the dispute. These cross-border relations also intersect with politics and the electoral processes when the right of dual citizenship is evoked by members of these bisected communities. Some have laid claim to citizenship of both countries as a result of belonging to one traditional state that straddles the international boundary. They thus stress their ‘right’ to participate in the political processes of both states.

An understanding of these meanings of the boundary and identity of the bisected communities would be useful in addressing some of these conflicts and electoral disputes.