Introduction

On 11 September 1952, Emperor Haile Selassie ratified the establishment of the federation between Ethiopia and Eritrea, thus sanctioning the end of British administration of the latter. The federation was dissolved ten years later, paving the way for the beginning of an armed struggle in Eritrea's Muslim lowlands. In the early 1970s, the liberation war spread to the predominantly Christian highlands, originally the main supporters of the federation with Ethiopia. This step was a turning point in the conflict, which culminated with the achievement of independence in 1993 (Iyob Reference Iyob1995; Redie Bereketeab Reference Bereketeab2017). The political trajectory of Eritrea from 1952 onwards has been mostly analysed through the lens of the armed struggle and the development of Eritrean nationalism, paying less attention to the institutional and economic connections that were unfolding at a regional level (Uoldelul Chelati Dirar Reference Dirar, Taddia and Berge2013: 246). This article is a partial attempt to broaden our understanding of this critical period in the country's history (Reid Reference Reid2014: 102). It takes into account the changes in centre–periphery relations between Ethiopia and Eritrea in the two decades (1952–73) following the creation of the federation. It does so through the lens of the relationship between imperial Ethiopia and the Eritrean-based financial institution with the most important links to the former colonial power: the Italian Banco di Roma. The trajectory of Banco di Roma offers an innovative perspective on the hidden struggles that underpinned the process of incorporation of the former Italian colony within the Ethiopian Empire.

In recent years, scholars have devoted growing attention to the relationship between governments and business groups in postcolonial Africa (Austin and Broadberry Reference Austin and Broadberry2014). Nevertheless, historians have mostly focused on the imperial side of the story (Decker Reference Decker2011; Uche Reference Uche2012; Morris Reference Morris2016), while African actors have tended to be depicted as passive recipients of their mise en dependence (dependency) or, alternatively, as nationalist vanguards struggling against the remnants of colonialism (Cooper Reference Cooper1994). In fact, local responses to foreign economic domination were more nuanced. The control of key outposts at the interface with the international system was crucial for reproduction of the African ‘gatekeeper’ state after independence. Those who exercised authority at the nodes where local societies met the external economy could manipulate revenues and patronage possibilities deriving from that point, including foreign loans and commercial deals (Cooper Reference Cooper2014: 30). Securing a direct relationship with international firms could be critical for subnational actors as well, because they could acquire control of ‘the relations with the exterior on which those who dominate the society base their power’ (Bayart Reference Bayart2000: 219). Not incidentally, in the turbulent years of decolonization, would-be secessionist forces struggled to preserve some link with financial institutions or business groups associated with the former metropolitan power (Boehme Reference Boehme2005). As has been argued elsewhere, ‘there is work to be done in historicizing these state formation trajectories’ (Jerven et al. Reference Jerven2012: 17) at the nodal points with the international system after the fall of colonial empires.

The process of decolonization in Eritrea was quite exceptional when compared with the rest of the African continent. The end of Italian rule did not bring the independence of the former colony, but triggered a competition between overlapping late colonial projects (Morone Reference Morone and Morone2018: 5). The country was placed under British military occupation until September 1952, when it was federated to Ethiopia under UN Resolution 390 of 1950. Before that date, the Italians had first tried to obtain the trusteeship of the territory and then subscribed to its split between Ethiopia and Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, in return for special status being assigned to the Italian-inhabited cities of Asmara and Massawa (Tekeste Negash Reference Negash2004). After the establishment of the federation, Eritrea remained an integral part of the former metropolitan power's sphere of influence, Italian firms dominating the most profitable sectors, such as industry, trade and commercial agriculture (Strangio Reference Strangio2009: 26–7; Tekeste Negash Reference Negash1997: 142).Footnote 1 Italian interests were protected by the principle enshrined in Resolution 390 and then incorporated into the federal constitution, which safeguarded the pre-existing rights of foreign nationals. Because of this legal umbrella, from 1952 Banco di Roma was able to keep a foothold in Eritrea, challenging the banking law in force in the rest of the Ethiopian Empire. Ethiopian authorities did not accept this situation passively, but differed on how to deal with the Eritrean exception. The Eritrean ruling establishment, in turn, exploited the presence of Banco di Roma to derive benefits that were usually reserved for sovereign entities, and temporarily succeeded in delaying the advancement of the Ethiopian Empire. Once Banco di Roma was deprived of its extraterritorial status, however, it suddenly became an instrument of central government institutions for subjecting the Eritrean economy to the needs of imperial statecraft.

Methodologically, this article is based on mostly untapped primary sources from the archives of the Italian Ministry for Foreign Affairs, the archives of Banca d'Italia and the Bank of England, the business records of Banco di Roma and Barclays Bank, the National Archives of the UK at Kew Gardens, the historical records of the International Monetary Fund and the national archives of Ethiopia. Any perceived over-reliance on Western sources is partially counterbalanced by a number of original Ethiopian government documents from the archives of Banco di Roma; these provide a first-hand account of the Ethiopian perspective. A cross-check analysis of these sources offers a deconstruction of the idea that the Ethiopian state was a monolithic entity committed to the eradication of Eritrea's autonomy. It also calls into question the rigid dichotomy that traditionally frames the Eritrean elite's reaction to annexation in terms of an uncritical collaboration or maximum resistance (Reid Reference Reid2007: 246). Banco di Roma acted as an interface that various institutions and individuals in Asmara and Addis Ababa could exploit in order to renegotiate the terms of their mutual relationship, as well as their connections to the external world and associated benefits (Hagmann and Peclard Reference Hagmann and Peclard2010).

Commerce, finance and state building in the Ethiopian Empire

The process of state building in twentieth-century Ethiopia has usually been analysed through the lens of the relationship between the ‘centre’ – the capital Addis Ababa, or, broadly speaking, the political structure of the Christian highlands – and the ‘peripheries’ incorporated at the turn of the nineteenth century (Bach Reference Bach, Fiquet, Hassen and Osmond2015). Centre–periphery linkages usually varied between two ideal ends. Certain regions preserved internal autonomy and quasi-sovereign prerogatives in their dealings with neighbours, acting as semi-independent enclaves within the empire. In return for this privilege, they were made directly tributary to the Crown or to a powerful provincial overlord (Triulzi Reference Triulzi, Donham and James2002). Others were firmly integrated within the political and economic structure of the highlands, the Ethiopian administration taking a much more rigid attitude in enforcing how and by whom local resources should be exploited (Donham Reference Donham, Donham and James2002). Control over long-distance trade played a critical role in the quest for political centralization. Growing incorporation within the global economy turned the power struggle between the Emperor and subnational rulers into a competition for command of customs posts along the main trading routes (Garretson Reference Garretson1979: 416). In this respect, the degree of control exercised by the central government in shaping the circulation of goods and capital flows at nodal points with the international system is a useful lens to evaluate the evolution of centre–periphery linkages within the Ethiopian state in the twentieth century. While commercial authorities in the south and the east were usually appointed by the central government, northern provinces retained the power to appoint their own naggadras – the head of the merchants – and set the terms of trade with neighbouring territories until 1936 (ibid.: 437).

The establishment of a fixed capital by Emperor Menelik II in 1889 and the construction of the railway from Addis Ababa to Djibouti marked a turning point in the relationship between Ethiopia and the international system. The construction of the railway placed the imperial residence at the intersection of a commercial network linking the coffee-producing southern regions to international markets, thereby providing new wealth and hard currency to the government's coffers (Pankhurst Reference Pankhurst1965; McClellan Reference McClellan, Donham and James2002: 186). The same rationale shaped the creation of the first banking institution in the country, the Bank of Abyssinia, in 1905. For Menelik, a more stable credit system was crucial to expand cash-crop production and, consequently, customs revenues. An important feature of this process was that the different activities associated with international trade were controlled for the most part by non-Ethiopian interest groups. Historically, Muslim merchants had controlled the import–export routes through the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, exploiting the fact that Christians were generally opposed to commerce (Pankhurst Reference Pankhurst1964). Gradually, they were paralleled by large European and Indian firms engaged in the trade of coffee and skins. The Indians in particular possessed connections in Ethiopia's three main commercial entrepots and monopolized the informal credit network that dominated the Ethiopian financial landscape (Schaefer Reference Schaefer1994: 60). Foreign interests also prevailed in the Bank of Abyssinia, which was controlled by British capital through the National Bank of Egypt (Schaefer Reference Schaefer1992).

This state of affairs had two main consequences. On the one hand, it created the ideal conditions for the development of a specific form of rentier capitalism ‘typified by speculation in property to generate profits through interests, rents, and capital gains’ (Schaefer Reference Schaefer2012: 53). The growing presence of foreigners opened up new avenues for economic accumulation to the Ethiopian aristocracy, who monopolized land ownership. The Emperor and the highest nobles could now make a fortune out of investments in land and buildings, which were then rented out to foreign businessmen (ibid.: 65). In this manner, Ethiopian rulers were able to create new patronage networks without resorting to the usual patterns of outward expansion for land and booty. On the other hand, however, foreign domination in the realm of credit and trade was a significant obstacle to the enforcement of state sovereignty across the national territory. While the Bank of Abyssinia had been established with the purpose of promoting fiscal centralization via international trade, it soon became clear that the institution was primarily a tool of British imperial ambitions (Schaefer Reference Schaefer1992: 367). The bank immediately opened new offices in Gore, Sayyo and Gambella, in the south-western part of the country. The underlying reason was to redirect Ethiopia's foreign trade towards Anglo-Egyptian Sudan through the Gambella border post, which had been leased to the UK a few years earlier. This decision was in stark contrast to the government's vested interest in commodities transitting through the capital Addis Ababa (Bahru Zewde Reference Zewde1987). Foreign control over trading flows also had negative consequences for the Ethiopian Empire's ability to project power to the periphery. Along the frontier with British Somaliland, British attempts to capture transborder commerce by extending diplomatic protection to Somali pastoralists and merchants clashed with the interests of the new Ethiopian administration in Jigjiga, which was struggling to enforce direct taxation and territorialize state authority (Barnes Reference Barnes, Feyissa and Hoehne2010; Thompson Reference Thompson2020).

Emperor Haile Selassie was well aware that, for Ethiopian sovereignty to be protected, he should secure a more direct grip on international trade and finance. From 1916 to 1930, European control at the nodal points with international markets had prevented the regent from purchasing modern weapons on international markets, making Ethiopia vulnerable to the ensuing Italian aggression (Marcus Reference Marcus1983). Not incidentally, the monarch's first act after enthronement was the dissolution of the Bank of Abyssinia and the creation, in its place, of the government-owned Bank of Ethiopia. It is unsurprising that, when the British liberated the country from Italian occupation and established the British institution Barclays as the new central bank, the Emperor's reaction was harsh. He refused to meet Barclays’ new manager in Addis Ababa, since the British administration ‘had never informed him that the bank was coming, and he was not going to recognize it until its presence had been satisfactorily explained’.Footnote 2 Such was Haile Selassie's opposition that, at the end of 1941, Barclays was already halting any plan for further expansion in Ethiopian territory.Footnote 3

In the summer of 1942, the Emperor re-established the Bank of Ethiopia under the name of the State Bank, while continuing his diplomatic campaign in favour of Barclays’ expulsion from the capital.Footnote 4 At the end of the year, in parallel with the evacuation of British soldiers from Addis Ababa, the British bank was forced to relocate to Asmara and relinquish any ambition in the Ethiopian financial sector.Footnote 5 By 1952, when the federation with Eritrea was approaching, the State Bank had successfully monopolized every banking activity in the country, simultaneously performing the functions of central bank, commercial institution and foreign exchange controller (Mauri Reference Mauri1967). The only exception was the World Bank-funded and government-owned Development Bank of Ethiopia, created to provide long-term loans to agricultural and industrial enterprises. This institution, however, would lose all its autonomy one year later, when its Polish governor was forced to resign in favour of a long-standing Indian servant of the Ethiopian government.Footnote 6

Banking and diplomacy in federal Eritrea, c.1952–62

When the federation between Ethiopia and Eritrea was established in September 1952, the Ethiopian government was forced to come to terms with the peculiar conditions of the local banking sector. Three foreign banks operated in Eritrea under protection of UN Resolution 390: the British Barclays and the Italian Banco di Roma and Banco di Napoli. All of them were almost exclusively focused on import–export trade, which was mainly managed by European and Arab merchants.Footnote 7 Barclays had also performed the functions of central bank until the transfer of power. For higher authorities in the Ministry of Finance and the State Bank of Ethiopia, the presence of European banks on Eritrean soil was an open challenge to the banking law in force in the rest of the empire. The American governor of the State Bank had a reputation for being hostile to any foreign interference that might challenge the monopoly of his institution, while middle-ranking Ethiopian officers looked at the liberalization of the banking sector with even greater suspicion.Footnote 8 It was no coincidence that, once the federation had been established and the functions of a central bank had been taken over from Barclays, the State Bank immediately attempted to drive its competitors out of Eritrea. The bank made it clear that it had exclusivity on foreign exchange operations, which were by far the most profitable commercial activity.Footnote 9 Such was the economic impact of this decision that Barclays, after careful scrutiny, opted to abandon Eritrea.Footnote 10

The reaction of Banco di Roma was different. The Italian bank was indirectly controlled by the Italian state through the government agency Istituto per la Ricostruzione Industriale (De Rosa Reference De Rosa1982). Far from being a merely commercial institution concerned with the maximization of profits, it was expected to serve the Italian national interest by encouraging import–export trade with Italy and supporting the large Italian community in Eritrea. Only after every opportunity in this area had been exhausted were the local subsidiaries authorized to diversify their lending portfolios.Footnote 11 That broader political calculations dominated over the maximization of profits is confirmed by the fact that the Eritrean subsidiaries ran contrary to the general rule, which prescribed that Banco di Roma's foreign branches be self-sufficient and collect working capital through deposits from local customers.Footnote 12 On the contrary, the Asmara branch was a constant beneficiary of cash transfers from the parent company. This happened even though there was no chance that these transactions would provide a profit, due to the high foreign exchange fees imposed by the State Bank of Ethiopia.Footnote 13

Ethiopian officials almost unanimously viewed the federation as a transitional step towards the full return of the lost northern province to the ‘motherland’, but they differed on the strategies to be adopted (Suleiman Reference Suleiman2013: 59–60). While the State Bank was able to claim sovereignty over banking regulations at the federal level, political power was firmly in the hands of the Crown through the office of the Special Representative of the Emperor, whose authority de facto superseded the office of Chief Executive of the Eritrean government (Tekeste Negash Reference Negash1997: 79). The posture of Emperor Haile Selassie towards Italian business in Eritrea was far more permissive than was that of his government's financial bodies: just two years before the establishment of the federation, the highest non-American official within the State Bank, who was renowned for enjoying the Emperor's trust, had reassured the Italian government of his determination to authorize the continuation of Banco di Roma's activity.Footnote 14 The intercession of the Crown would prove to be crucial to overcome the deadlock on foreign exchange transactions. Banco di Roma received permission to engage in this activity under the supervision of the State Bank Exchange Control Office, thereby guaranteeing the bank's survival.Footnote 15

The Crown had several reasons for supporting the presence of the Italian bank. First, Banco di Roma's preferential focus on import–export operations translated into growing indirect revenues from tariffs on external trade.Footnote 16 Eritrea was the natural entrepot of northern Ethiopia's external trade, thanks to earlier Italian colonial efforts to redirect the commerce of Begemder and Gojiam from the Sudanese route towards the ports of Massawa and Assab (Ahmad Reference Ahmad1997). Now, according to the federal arrangement, Addis Ababa had the right to retain customs duties on goods in transit through these ports and whose origin or final destination was not Eritrea. Given the difficulties involved in assessing the exact amount of Ethiopian trade, authorities nonetheless retained a large share of revenues. They were supposed to grant a yearly lump sum of Eth $4,630,000Footnote 17 to the Eritrean government, only a portion of which was then actually transmitted to Asmara (Tekeste Negash Reference Negash1997: 139).Footnote 18

Second, the fact that Banco di Roma was able to mobilize liquidity for the purpose of encouraging trade with Italy had a high diplomatic value, since it increased the autonomy of the Ethiopian government in the international arena and reduced its dependence on the USA and the UK for access to hard currency. In fact, Banco di Roma's business policy authorized the Ethiopians to bypass the strict regulations imposed by US governors and British auditors at the State Bank of Ethiopia, which was committed to encouraging international trade almost exclusively within the dollar and sterling areas.Footnote 19 Minister of Commerce Ylma Deressa remarked on his determination to diversify sources of hard currency during a private meeting with the Italian ambassador in 1952, suggesting that private commercial banks could be a useful tool for promoting import–export flows with Italy without infringing the rules imposed by Anglo-American advisers.Footnote 20

The presence of Banco di Roma was a valuable asset in the hands of the Eritrean ruling class, which was eager to get access to the same mortgage loans that the Development Bank and the State Bank were granting to the Ethiopian aristocracy in the south. In spite of the establishment of a subsidiary of the State Bank in Asmara, the latter's credit policy was initially highly restrictive and focused on the import–export trade, like the European banks.Footnote 21 Business records from Banco di Roma suggest that, in the first years of the federation, the Italian bank was equally reluctant to issue mortgage loans, since these operations were beyond its statutory prerogatives. An exception was made for a few selected Italian firms,Footnote 22 while Africans were generally prevented from accessing long-term credit. This orthodox stance was soon to change under pressure from Eritrean interest groups, however. In 1956, a press campaign began to be waged by a number of government-controlled Eritrean newspapers, which accused the Italian bank's credit policy of co-responsibility for the deterioration in local economic conditions. For the management of Banco di Roma, these allegations had a clear political nature.Footnote 23 Eritrean media advocacy was accompanied by institutional initiatives to expand competition in favour of local business. In the summer of 1956, the Eritrean Assembly authorized the creation of the Eritrean Agricultural and Aquatic Credit Institute, a government-owned bank that was expected to lend to Eritrean citizens engaged in fishing and agriculture.Footnote 24 The experiment did not last long, but it seems to have been instrumental in moderating the conservative attitude of Banco di Roma towards providing finance to Africans.

Starting in 1958, the Asmara branch began to issue mortgage loans under the counter to prominent members of the Eritrean administration and their relatives, including to the Chief Executive of the Eritrean government, the renowned pro-unionist Asfaha Woldemichael, and his wife. For the Italian bank, these transactions were nothing less than bribes in return for political protection. The local management in Asmara was of the opinion that these facilities were crucial to secure the support of the local ruling class, even though the inspectors dispatched from Rome described the operations as irrational from an economic point of view.Footnote 25 The nature of the loans also highlights how borrowing was aimed at speculation in property to generate rent, rather than to foster long-term productive investments. Asfaha Woldemichael obtained Eth $50,000 to purchase seventy-one shares of the Barattolo share company, a large Italian firm that offered generous dividends to shareholders.Footnote 26 Alongside informal payments to the local ruling class, the bank also engaged in the unorthodox policy of granting small loans to Eritrean clients working in wholesale trade, retail, livestock and artisanal textile production, thereby contributing to the emergence of local petty entrepreneurship.Footnote 27 In this way, the Italian management was able to obtain recognition from the Eritrean administration for its role in the development of the former colony, demonstrating the importance of maintaining an alternative financial outlet to the State Bank of Ethiopia.Footnote 28

The desire to cultivate a preferential relationship with the Eritrean elite stemmed from the fear that the protection of the UN resolution was not enough, and that hostile government circles in Addis Ababa would exploit every means at their disposal to close down the offices of Banco di Roma. The most vocal representative of Ethiopia's economic nationalism was the Minister of Finance Mekonnen Habte Wolde, who was also the head of the Association of Ethiopian Patriots. Mekonnen Habte Wolde was renowned in World Bank circles for his aggressive attitude towards foreign firms, which he accused of exploiting the country's economic wealth.Footnote 29 If one looks closer, however, it appears that the Minister of Finance's hostility towards Banco di Roma was driven by material factors related to the impossibility of extracting rents from the bank, rather than by ideological opposition to Italian capital in itself. In 1956, for instance, an envoy of Banco di Roma visited Addis Ababa to talk with him about the possibility of opening a liaison office in the capital. Mekonnen did not reject the request in principle, but he made it clear that, for the application to be successful, the new agency would have to be based in a building he had recently constructed (De Rosa Reference De Rosa1982: 286).

A semi-independent financial enclave, c.1962–66

On 15 November 1962, the federal arrangement suddenly came to an end and Eritrea was incorporated as the fourteenth province of the Ethiopian Empire. In principle, this meant that Banco di Roma was operating in a juridical limbo. The dissolution of the federation deprived the Italian group of the international protection granted by the UN resolution. According to the law, the State Bank of Ethiopia was the only authorized banking institution in the country. The ground was cleared a few months later, in 1963, when Proclamation 206 introduced a new banking law. The proclamation split the State Bank of Ethiopia between the National Bank and the Commercial Bank, with the former maintaining all the prerogatives typically associated with a central bank (Befekadu Degefe Reference Degefe and Bekele1995). The Commercial Bank would engage in commercial activities in competition with other foreign banks, which were only allowed to operate on condition that they established joint ventures with a majority Ethiopian shareholding. The trend towards the indigenization of the banking system was further confirmed by the fact that, for the first time in history, the National Bank of Ethiopia was headed by an Ethiopian national: the former Vice-Minister of Finance, Menasse Lemma, overcame competition from another American banker, Donald Gunther.Footnote 30

The following events once again made clear the existence of different perspectives within the Ethiopian government on how to deal with incorporating the northern province. For the National Bank, the proclamation offered an opportunity to obtain recognition of its sovereign prerogatives and put an end to the Eritrean exception. Not coincidentally, Governor Menasse Lemma immediately approached Banco di Roma to request adaptation to Ethiopian law, in terms of both capitalization and shareholding structure.Footnote 31 The Italian bank was nonetheless determined to maintain full control of its Eritrean subsidiaries. After careful scrutiny, Italian bankers called for a diplomatic intervention by the Italian government, with the objective of preserving the bank's existing privileges at any cost.Footnote 32 Emperor Haile Selassie had no interest in causing an international controversy on the dissolution of the federation. The Italian diplomatic mission, on the other hand, was willing to exclude unilateral action as long as no damage was caused to the interests of the Italian business community (Monzali Reference Monzali, Perfetti and Ungari2011). At the beginning of 1964, the new governor general of Eritrea communicated to Banco di Roma that the Emperor had accepted its proposal, thereby exempting the bank from having to adapt to the new banking law.Footnote 33 There was one limitation, however: the Italian bank was not authorized to operate beyond the borders of the Eritrean province.

It would be misleading to explain this decision simply as a consequence of the Italian government's external intervention. In fact, the new arrangement reproduced the typical linkage between the Ethiopian Crown and the semi-independent enclaves that still prospered in other peripheral regions of the country (Puddu Reference Puddu2016). Banco di Roma was placed in a direct relationship with the Crown, bypassing the formal hierarchy that submitted commercial banks to the sole authority of the National Bank of Ethiopia. The bank's status was not regulated by Proclamation 206, but depended on an imperial decree. This created an exception that suspended the ordinary law for the benefit of Banco di Roma. In return, the Italian bank would make informal payments disguised as commercial loans to the Crown and its local associates. From the perspective of the Ethiopian ruling class, however, these levies were not dissimilar to the traditional tribute placed on other semi-independent enclaves – ‘k'urt gibr ager', the land of fixed tribute – across the country (Meckelburg Reference Meckelburg, Mbah and Falola2017). Tribute was the price of autonomy from central control. At the same time, it made it possible for a close circle surrounding the Emperor to concentrate surplus extraction in their own hands at the expense of formal state institutions.Footnote 34 Among the beneficiaries of these informal tributes were Fisseha Woldemariam, a deputy in the Ethiopian parliament, the aforementioned Asfaha Woldemichael, and Fitawari Messai Wendwessen, a prominent member of the Shoan aristocracy and cousin of the governor general of Eritrea.Footnote 35 The most important beneficiary, however, was the governor general himself, Asrate Kassa, who was rewarded with large overdrafts of hundreds of thousands of Ethiopian dollars. The destination of this money, once again, was speculation in property to generate rents and capital gains. Asrate Kassa purchased buildings and stocks from other Italian companies, including the Barattolo textile factory.Footnote 36 The connection between tribute and maintenance of the Crown's political protection was expressly acknowledged by the Italian management in Asmara. In the immediate aftermath of the promulgation of the imperial decree, the local bankers recommended to the board of directors that they authorize any loan application by the governor general without delay, due to his critical role in protecting Banco di Roma from the aggressive posture of the National Bank.Footnote 37

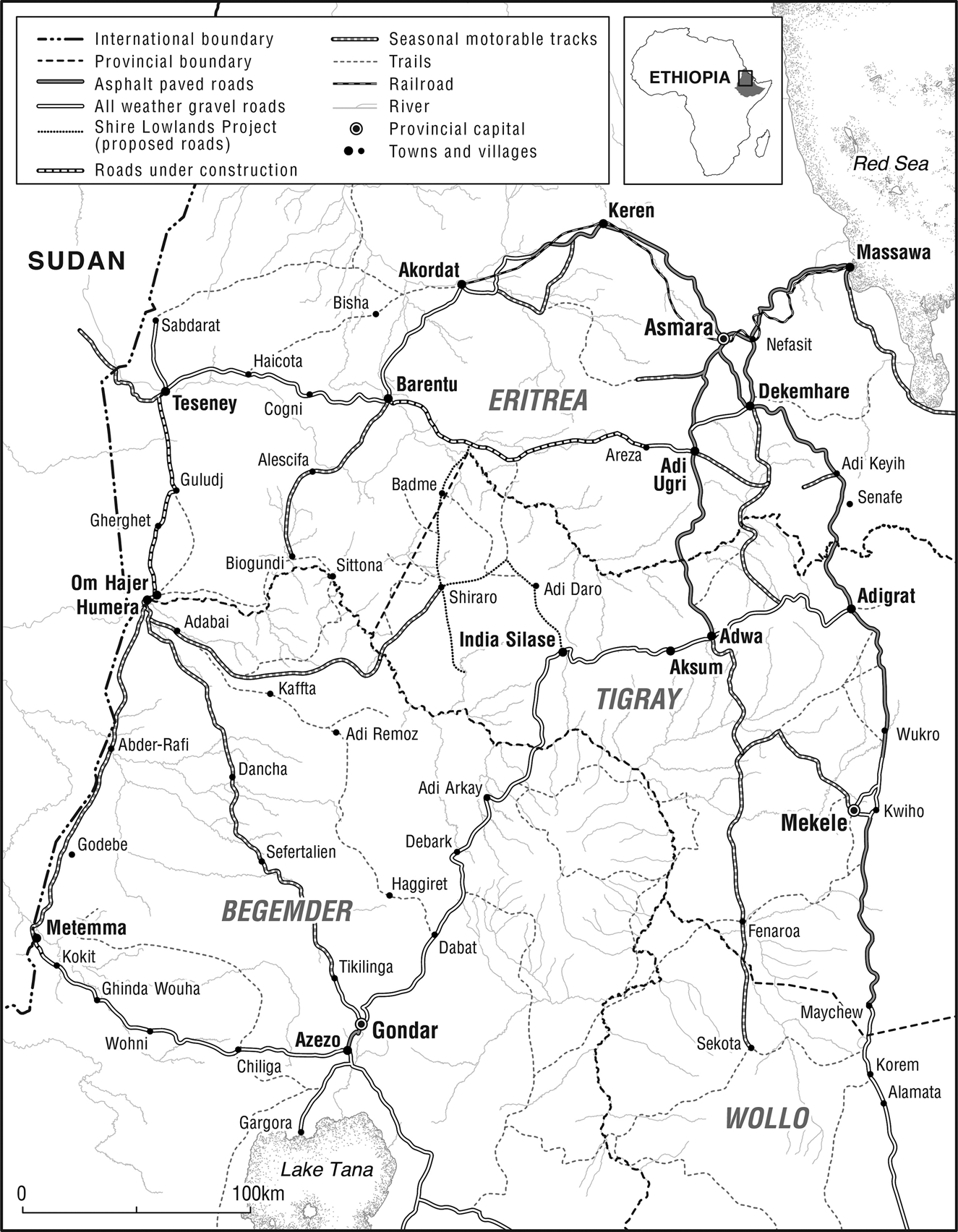

While the individuals mentioned above were closely associated with the imperial establishment in Addis Ababa, the Eritrean ruling class in the provincial administration also had its share of benefits. One beneficiary was a renowned representative of the pro-autonomy wing of the Eritrean political spectrum, Deputy Governor General Tesfayohannes Berhe (Akyeampong and Gates Reference Akyeampong and Gates2012: 31). Tesfayohannes placed his relatives at the forefront of the process of Africanizing Banco di Roma's labour force: his nephew, for instance, was recruited as manager of a local branch.Footnote 38 Another beneficiary of the bank's largesse was the mayor of Asmara, Haregot Abbai, who invested his borrowings in the purchase of real estate.Footnote 39 Haregot Abbai was also the owner of the bus transportation company connecting Asmara to Massawa, which was a privileged customer of Banco di Roma despite the firm's alleged financial troubles.Footnote 40 All these transactions highlight another element: the Eritrean ruling elite had an interest in ensuring Banco di Roma's exclusive links to the province. In fact, the bank's lending activity in favour of Italian import–export traders along the Asmara to Massawa route (see Figure 1) offered invisible benefits that could not be immediately accounted for, such as investment opportunities in the expanding transportation business or in the western lowlands’ commercial agriculture.

Figure 1 Transportation network between Eritrea and northern Ethiopia. Source: Institute of Ethiopian Studies, TAMS Agricultural Development Group, The Humera Report: resources and development planning, January 1974, p. 188.

The fact that Banco di Roma was authorized to operate only within the boundary of Eritrea amounted to a sort of recognition of Eritrea's special status compared with other provinces of the empire. In turn, Asmara could exploit the Italian bank as a gatekeeper to obtain independent access to the rent of foreign aid from its former colonial master, without having to rely on intermediation from the central government in Addis Ababa. Indeed, it is worth noting that the Eritrean branch of Banco di Roma was effectively operating as a shadow division of the Italian ministries of commerce and foreign affairs, performing political functions that were usually associated with the work of an international aid agency. The contemporaneous presence of top executives from Banco di Roma on the boards of other Italian state-owned import–export agencies facilitated the arrangement of informal aid packages at favourable interest rates, thereby bypassing the normal bureaucratic channels both at home and in the host country. For instance, when the Ethiopian parliament rejected ratification of the Italian aid programme in 1966, the director of the Ethiopian Investment Corporation (EIC) in Asmara knocked on the door of Banco di Roma to obtain credit advances for the imminent import–export season.Footnote 41 Once it had provided first-hand support to cover the most immediate needs, Banco di Roma mediated with the Italian public company Mediobanca for the supply of export credit to the EIC with a longer repayment period, thereby circumventing the veto powers of both the Italian and the Ethiopian parliaments.Footnote 42

Centralization, c.1967–73

For Banco di Roma, the rationale behind cultivating these links was to maintain its established position in Eritrea. The institution was concerned in particular with preserving control of the bank accounts of the municipal treasuries in Asmara and Massawa, which provided a significant source of liquidity for domestic operations. These facilities were nonetheless being threatened by the aggressive stance of the Commercial Bank of Ethiopia, which insisted on placing all institutional accounts in Eritrea under its own control.Footnote 43 Indeed, the National Bank of Ethiopia did not accede to the imperial decree passively; rather, it struggled to enforce its sovereign prerogatives across the Eritrean financial landscape. This rigid attitude was not unexpected: the Ethiopian deputy governor of the State Bank was renowned for his opposition to liberalization and the entry of foreign banks,Footnote 44 and the new governor, Menasse Lemma, shared these opinions. Immediately after the enactment of the imperial decree, the CEO of Banco di Roma wrote to the governor to assure him that the maintenance of special privileges was not supposed to be ad libitum, and that his bank would take steps to align with the national law in the near future.Footnote 45 The governor's response was paradigmatic of his will to bring Banco di Roma under the formal hierarchy of the state:

I expected that by this time an application would have been submitted to the Bank for an interim license to continue your present banking business in Ethiopia, supported by a firm intention on the part of your Bank to … meet the requirements of the Proclamation … The continued undetermined situation after such a lapse of time is now, however, a matter of real concern to the National Bank of Ethiopia.Footnote 46

Soon afterwards, Menasse Lemma denied authorization for the establishment of a new branch of Banco di Roma in Addis Ababa and began to impose restrictions on the remittance of the bank's dividends to the parent company. He also exploited the National Bank's supervisory powers in the area of foreign exchange to prevent transactions in US dollars and affect Banco di Roma's capacity to engage in import–export operations with Italy.Footnote 47 The determination of the National Bank to enforce its statutory powers without exception was made even clearer in June 1965, when Banco di Roma attempted a compromise by creating a joint venture without voting rights for Ethiopian shareholders. The governor rejected the proposal and once again threatened to impose sanctions against the Italian bank, arguing that his refusal had been expressed ‘well in advance of the forthcoming export season, in order that you might take steps to regularize your position’.Footnote 48

The National Bank's strategy was a success. In March 1967, Banco di Roma finally opted for adaptation to Ethiopian law, after determining that it was not possible to run its business in open opposition to the country's main banking institution.Footnote 49 However, the round of negotiations that preceded this decision is evidence of the fact that the Eritrean ruling elite perceived this move as an existential threat and sought to rely on Banco di Roma in order to resist full incorporation within the empire. The deputy governor general of Eritrea, Tesfayohannes Berhe, immediately declared his full support for the Italian bank in the controversy and committed himself to lobbying on behalf of Banco di Roma in government circles.Footnote 50 In the meantime, he insisted that the bank should not renounce its extraterritorial status and simply align with the capital requirements imposed by the law.Footnote 51 Once it was clear that Banco di Roma was determined to satisfy the National Bank's demands, he made a last attempt to preserve Banco di Roma's Eritrean character by tracing a parallel between Eritrea's and Italy's joint national interest in resisting the advance of Ethiopian statecraft. In a conversation with the director of Banco di Roma's Asmara branch, Tesfayohannes accused the governor of the Central Bank of Ethiopia of being a blind nationalist driven by anti-Italian sentiments, suggesting that the only way to protect the bank's long-term interests would be to appoint an individual from the Eritrean administration to the presidency of the joint venture.Footnote 52 So it is no wonder that he was greatly dismayed by the appointment of the pro-unionist Asfaha Woldemichael, who was serving as Minister of Justice in the central government at the time.Footnote 53

The transfer of the joint venture's headquarters to Addis Ababa had far-reaching effects on the business strategy of the Italian bank, because the loss of autonomy authorized state institutions in the capital to exert growing influence over its business conduct. The assertiveness of the supporters of economic centralization in Addis Ababa was accentuated by the widespread perception that Italian business was sympathetic to the activities of Eritrean rebels (Haile Muluken Reference Muluken2014: 382) and by the severe financial crisis that affected the government budget after the closure of the Suez Canal in 1967.Footnote 54 This marked a turning point in the relationship between the National Bank of Ethiopia and Banco di Roma, because the former's concern about the reduction in foreign exchange reserves increasingly clashed with the Italian bank's focus on trading operations and the repatriation of dividends.Footnote 55 That Menasse Lemma was suspicious of the Italian bank's complicity in the illicit outflow of hard currency is indirectly confirmed by two elements. First, Banco di Roma was the main lender to Società Elettrica per l'Africa Orientale, an Italian electric power company that was at loggerheads with the National Bank over the repatriation of profits to Italy.Footnote 56 Second, there was widespread belief that foreign trading firms were inflating the volume of their activities for the purpose of remitting capital abroad undercover. This suspicion is confirmed by the record books of the National Bank of Ethiopia for the year 1976, which contain a number of letters addressed to foreign merchants: they were accused of being millions of US dollars in debt with the central bank.Footnote 57

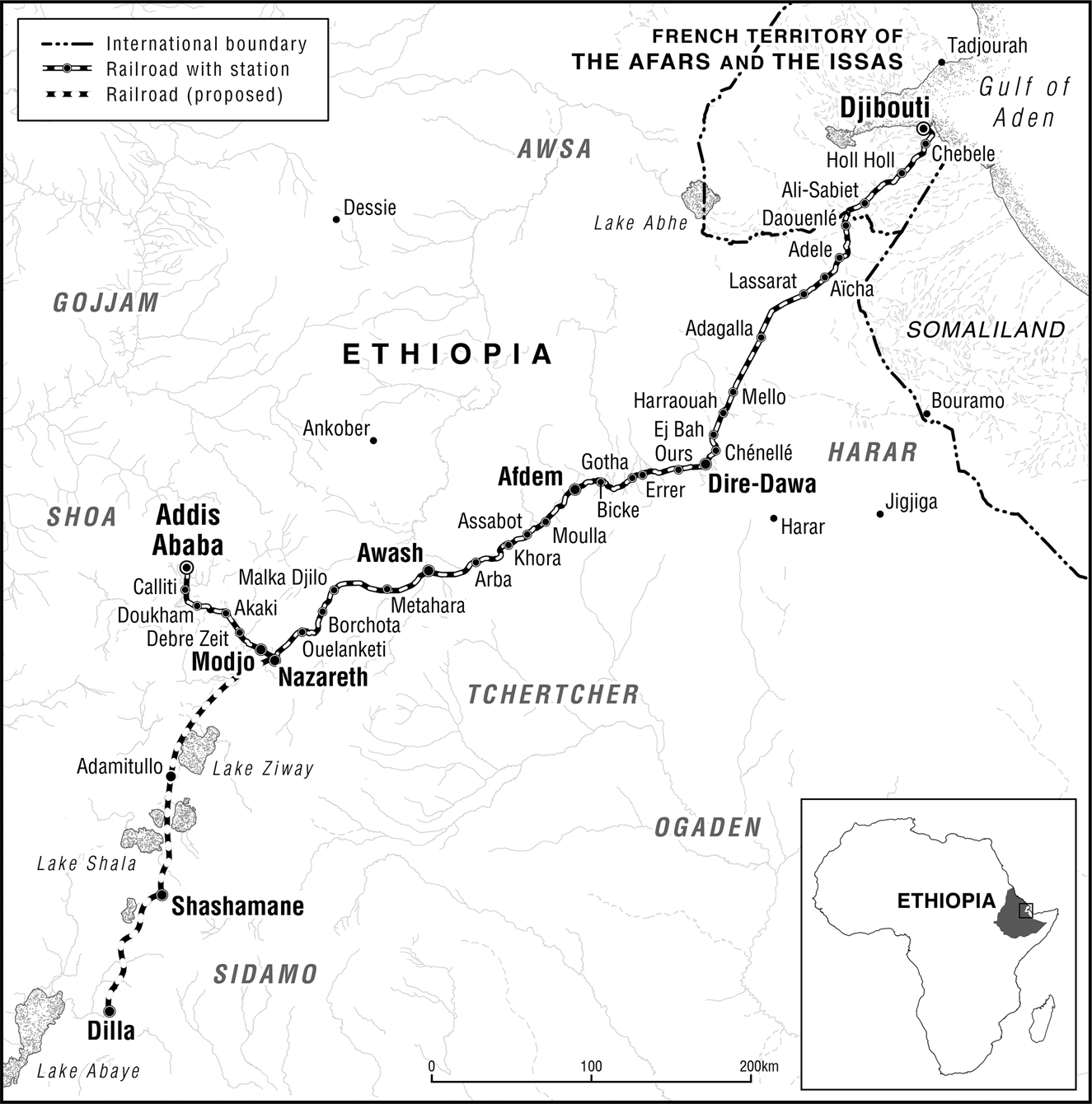

Indeed, the countermeasures adopted by the National Bank against Banco di Roma were dictated by the attempt to enforce direct control over the circulation of capital flows at the nodal points with international markets, thereby preventing hard currency from draining out of the country. This strategy developed along two main directions: first, by reducing the movement of capital and goods between Italy and Eritrea under the patronage of Banco di Roma; and second, by redirecting the Italian bank's geographical focus southward.Footnote 58 In the two years that followed, the Eritrean import–export activities of Banco di Roma suffered a severe backlash following rumours of the imminent nationalization of the Eritrean oil seed export trade, which up to that point had been managed by European traders with ties to Banco di Roma. In addition, the National Bank exerted pressure and swiftly succeeded in establishing two new branches of the Italian institution in Assab and in Modjo – a small trading post on the Addis Ababa to Djibouti railway line (Figure 2) – on the grounds that the area was not properly served by other banks.Footnote 59 The side effect of this policy was that import–export trade volumes financed by the Italian bank gradually shifted from the Asmara to Massawa route, which was dominated by Italian and Eritrean business groups, towards the Addis Ababa to Assab and Addis Ababa to Djibouti corridors, which were under the direct control of the central government and associated firms (Tekeste Negash Reference Negash1997: 142; Bahru Zewde Reference Zewde2001: 196–7).

Figure 2 Addis Ababa to Djibouti railway. Source: Jean-Pierre Crozet, ‘Le Chemin de fer Franco-Ethiopien et Djibouto-Ethiopien Railway: Djibouti – Addis-Abeba’, <http://train-franco-ethiopien.com>.

There was a further change in the area of surplus extraction, because the Italian bank's compliance with the new banking law sanctioned the end of the informal tributary arrangement between Banco di Roma and the Ethiopian and Eritrean ruling classes in Asmara. Italian bankers in Ethiopia displayed a growing reticence about increasing their financial exposure in favour of politicians based in the northern province, in the belief that the key to political influence was now firmly entrenched in Addis Ababa.Footnote 60 A case in point was that of the mayor of Asmara, Haregot Abbai, whose overdraft with Banco di Roma had increased from Eth $10,000 in 1963 to Eth $200,000 in 1966. This largesse had been motivated by the fact that Haregot Abbai was shielding the Italian institution from the Commercial Bank's attempt to take control of the Asmara municipality's bank accounts.Footnote 61 Nevertheless, the mayor would not receive any additional credit from Banco di Roma in the years to come, in spite of repeated requests for new banking facilities. The fact that, in 1969, the municipality of Asmara suddenly decided to transfer management of the city treasury's bank accounts to the state-owned Commercial Bank apparently confirmed that Banco di Roma's privileged position in Eritrea was gone.Footnote 62

This shift in institutional leverage allowed the National Bank and the Ministry of Finance to take full control of Banco di Roma's capital flows and submit them to the needs of fiscal centralization. In December 1967, at the onset of the closure of the Suez Canal, the governor of the National Bank summoned the new director of Banco di Roma–Ethiopia to demonstrate his determination to make Banco di Roma's business policy consistent with the orientation of the central government in favour of import substitution. In particular, the governor underlined the new government policy of favouring commercial banks ‘operating in sectors of national interest at the expense of those working in import–export trade’.Footnote 63 The real intentions of the National Bank became clear in 1969, following the enactment of new banking regulations that authorized the issue of government bonds to cover the growing state deficit.Footnote 64 Just prior to the first issue, the Minister of Finance met the Italian director general of Banco di Roma–Ethiopia to stress the great importance he attached to a positive reaction from foreign commercial banks. In return for financial support, he committed himself informally to turning a blind eye to the problems affecting Banco di Roma's legal reserves.Footnote 65 Italian bankers did not miss the opportunity to scale up in favour of the government: they subscribed to the highest amount of bonds at an interest rate lower than those offered by any other bank, the state-owned Commercial Bank included.Footnote 66

Even though accommodating the National Bank did not spare Banco di Roma from nationalization in 1975, this conduct had far-reaching consequences for the Eritrean economy, which was entering a downward spiral (Okbazghi Yohannes Reference Yohannes1991). Banco di Roma had subsidized the Eritrean elite and the Asmara to Massawa trading hub through the infusion of hard currency from the parent company. Now, however, Asmara was serving as a collector of capital to be transferred to Addis Ababa for the purchase of treasury bonds.Footnote 67 Between 1967 and 1969, credit facilities released by the Asmara branch decreased from Eth $25,500,000 to Eth $12,100,000.Footnote 68 In 1969, the investments of the Addis Ababa headquarters amounted to Eth $15,200,000. The critical difference was that, in the same year, the Addis Ababa branch mobilized liquidity from its customers for Eth $10,500,000, while Asmara accounted for more than Eth $21,000,000.Footnote 69 Arguably, these patterns affected large commercial firms to a lesser extent, since they could easily find alternative sources of lending or move elsewhere in search of other business opportunities. It was the Eritrean urban entrepreneurs who had emerged in the previous two decades, thanks in part to Banco di Roma's lending policy, who suffered the most from the credit crunch, thereby expanding the numbers of those who were calling the very legitimacy of Ethiopian rule into question.

Conclusions

This case study shows the complexity of African responses to European economic dominance after decolonization. State actors at the national and subnational level actively manipulated their relationship with powerful multinational groups in order to gain access to economic and political resources that were not available internally. While the Ethiopian government originally rejected the presence of foreign banks in Addis Ababa, it willingly recognized the special status of Banco di Roma in the Eritrean periphery in order to diversify the portfolio of financial partners and prevent full dependence on British and US markets. The Eritrean ruling class, on the other hand, actively encouraged the reproduction of privileged links with the former colonial master. The extraterritorial nature of Banco di Roma gave to both parties the leverage needed to shape the bank's lending policy according to their own needs. Ethiopian officials engaged in an updated form of rentier capitalism, investing the tributary proceeds in financial stock and real estate. Eritrean elites were able to perform quasi-sovereign prerogatives in the international financial arena, obtaining access to otherwise unavailable sources of capital and hard currency at subsidized interest rates. They also exploited Banco di Roma's focus on import–export trade to preserve the centrality of Eritrean commercial routes, entering into new businesses in cash-crop agriculture, transportation and trade.

From the perspective of imperial history, the extraterritorial status enjoyed by Banco di Roma might be framed as the consequence of Italian ‘neo-colonial’ attitudes; however, the trajectory of the Italian bank was deeply shaped by the conditions it encountered on the ground. The political economy of imperial Ethiopia's banking governance in Eritrea paralleled the technologies of rule adopted in other regions of the empire that had been conquered only recently. This reminds us that the Ethiopian state was not a monolithic entity eager to put an end to Eritrean autonomy at any cost. There was a dichotomy between the flexible and profit-oriented approach of the Crown and its associated establishment in Asmara, which were prone to granting substantial autonomy in return for tribute, and the more statist-oriented approach of the emerging bureaucracy in Addis Ababa, which was eager to enforce full sovereignty and territorialize state power at the nodal points with the international system.

The National Bank's success in the quest for financial centralization was a pyrrhic victory. In the short term, it made it possible to drain resources out of Eritrea and redirect them in support of the central government coffers. Nevertheless, it also paved the way for the definitive alienation of those sectors of Eritrean society that had previously come to terms with the post-federation political arrangement. According to this perspective, the case study suggests that the dynamics behind the emergence of the Eritrean armed struggle in the highlands in the early 1970s were closely connected to developments in Ethiopia and the wider region.

Acknowledgements

Research for this article was sponsored by the PRIN project ‘Monetary transitions: the introduction of colonial currencies in East Africa and their impact on local institutions and societies’, headed by Karin Pallaver, University of Bologna. An earlier draft of this article was elaborated during a visiting research stay at the African Studies Centre in Leiden in 2018; it was then refined during a visiting research stay at the Department of History at King's College London in 2019. I would like to thank Massimo Zaccaria, Uche Chibuike Uche, Stefano Bellucci, Sarah Stockwell and Uoldelul Chelati Dirar for their comments on earlier drafts of this article.