The remit of antipsychotic medication has expanded beyond the treatment of schizophrenia and related psychosis into many other areas, including bipolar affective disorders, psychotic and treatment-resistant depression, dementia and delirium (Reference Kupfer and SartoriusKupfer & Sartorius, 2002). Recent advances have led to the suggestion that first-line treatment for schizophrenia should include atypical antipsychotics, but these drugs cannot be assumed to be equally safe (Table 1) or, indeed, equally effective. One area that is important for all psychotropic drugs is their cardiac safety (Box 1). Some sources caution against the use of butyrophenones such as haloperidol (Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, 2005), others are more concerned with thioxanthenes such as thioridazine (Griffiths & Flannagan, 2005), whereas others caution against intravenous administration (National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2002). These recommendations, regardless of their evidence base, will have considerable effect on the emergency, acute and maintenance use of antipsychotics (Reference Bateman, Good and AfshariBateman et al, 2003).

Table 1 Classification of antipsychotic medication in terms of risk of cardiac arrhythmias

| Drug | Chemical structure | Risk of cardiac arrhythmias |

|---|---|---|

| Typical antipsychotics | ||

| Chlorpromazine | Aliphatic phenothiazine | Higher |

| Pimozide | Diphenylbutylpiperidine | Higher |

| Thioridazine | Piperidine | Higher |

| Trifluoperazine | Piperazine | Lower |

| Haloperidol | Butyrophenone | Lower |

| Sulpiride1 | Substituted benzamide | Lower |

| Atypical antipsychotics | ||

| Clozapine | Dibenzodiazepine | Higher |

| Quetiapine | Dibenzothiazepine | Lower |

| Risperidone | Benzisoxazole | Lower |

| Amisulpride | Substituted benzamide | Lower |

| Olanzapine | Thienobenzodiazepine | Lower |

| Zotepine | Dibenzothiepine | Lower |

Box 1 Cardiovascular adverse effects of anti-psychotic drugs

Common

Orthostatic (postural) hypotension

Syncope

Rare

Reduced heart rate variability

Prolongation of the QT/QTc intervals

Widened QRS complex

Very rare

Ventricular tachycardia

Torsades de pointes

Myocarditis

Cardiomyopathy

Pericarditis

Cardiac arrest and sudden cardiac death

There is now unequivocal evidence that many typical antipsychotics increase the risk of ventricular arrhythmias and cardiac arrest (Reference Ray, Meredith and ThapaRay et al, 2001; Reference Liperoti, Gambassi and LapaneLiperoti et al, 2005). Evidence to date also supports an association between many atypical antipsychotic drugs and the occurrence of unexplained sudden death (see Part 1 of this overview: Reference Abdelmawla and MitchellAbdelmawla & Mitchell, 2006).

Clinicians must be aware of the factors that influence cardiac safety in patients prescribed antipsychotics. Of at least equal importance, they must be able sensibly to choose for each patient an antipsychotic agent with minimal iatrogenic adverse effects and to monitor patients during treatment. We will look at each of these in turn.

Can clinicians estimate the risk of serious adverse events?

Differences between antipsychotics

Available evidence does not yet allow accurate comparison of the quantitative risk of serious cardiovascular side-effects or sudden cardiac death for all antipsychotics, not least because several agents have not been examined in sufficient detail. Nevertheless, an elevated risk of serious adverse cardiac events or sudden cardiac death has been documented for thioridazine, clozapine, droperidol, pimozide, pipamperone and sertindole. We suggest that these are considered higher-risk antipsychotics in terms of serious cardiac effects. Haloperidol, quetiapine, risperidone, chlorpromazine and trifluoperazine have a tendency to extend the QT interval even at therapeutic doses, but their link with sudden cardiac death is not yet clarified. Amisulpride, aripiprazole, olanzapine, sulpiride and zotepine have not been linked with an elevated risk of sudden cardiac death or QTc prolongation. In terms of sudden cardiac death these appear to be lower-risk antipsychotics. However, further data may change this suggested classification. For more information see Part 1 of this overview (Reference Abdelmawla and MitchellAbdelmawla & Mitchell, 2006).

Influence of moderating variables

A large number of variables influence the likelihood of antipsychotic-induced sudden death. The two most important are pre-existing heart disease and the total dose of antipsychotic that is bioavailable to the heart. Important types of heart disease linked with sudden cardiac death include ischaemia, dilated cardiomyopathy and left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Symptoms such as dyspnoea, syncope, dizziness, intermittent claudication and cognitive impairment should raise the suspicion of a systemic vascular disease and prompt investigations for heart disease (see below). Demographically, sudden cardiac death is more likely in elderly people and in women.

Evidence suggests that an increase in the bioavailable dose of antipsychotic medication rather than the route of administration or underlying condition is the most important drug-related variable (Reference Waddington, Youssef and KinsellaWaddington et al, 1998; Reference Hennessy, Bilker and KnaussHennessy et al, 2002). Factors that influence the total bioavailable dose include frequency of dosing and polypharmacy. In turn, polypharmacy and high dosing are influenced by the psychiatrist's attitudes, nurses’ requests for more drugs and, of course, the patient's clinical condition (Reference Diaz and de LeonDiaz & de Leon, 2002; Reference Ito, Koyama and HiguchiIto et al, 2005). Although it may be an oversimplification to rule out high-dose prescribing, clinicians must bear in mind a different balance of risk v. benefits in this case. Drug–drug interactions are widely considered to be important, and the clearest evidence for an increased risk relates to pharmacodynamic interactions (see ‘Drug interactions’ below).

Risk associated with rapid tranquillisation

There is an elevated risk of sudden collapse when antipsychotic medications are given during a period of high physiological arousal (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 1997). Some cases have involved serious cardiac events but rarely sudden cardiac death (Reference Jusic and LaderJusic & Lader, 1994). The mechanism is not fully understood, but one hypothesis is that physical restraint of the patient may inadvertently restrict breathing and cause greater cardiac strain, resulting in hypoxia and myocardial irritability. This suggests that the method of control and restraint is of key importance (Reference O'Brien and OyebodeO'Brien & Oyebode, 2003). We could find no evidence from carefully controlled studies that intravenous administration of antipsychotics is more dangerous than either the intramuscular route or oral dosing (Reference Santos, Beliles, Arana, Stoudemire and FogelSantos et al, 1998; Reference McAllister-Williams and FerrierMcAllister-Williams & Ferrier, 2002).

Patients requiring rapid tranquillisation should be closely monitored for clinical response, personal safety and adverse effects, and caution is advisable, particularly if repeated doses are given over a short period.

Cardiovascular screening of patients starting antipsychotics

Clinical history

A careful history will help elucidate any pre-existing cardiac disease, including heart failure, myocarditis, myocardial infarction and cardiac arrhythmias. One genetic syndrome is of note. The congenital long-QT syndrome (LQTS) predisposes to future serious cardiac events, and it may be indicated by recurrent syncope or a family history of early sudden death. Left ventricular hypertrophy, ischaemia and a low left ventricular ejection fraction are particular risk factors for sudden cardiac death and torsade de pointes (see Part 1: Reference Abdelmawla and MitchellAbdelmawla & Mitchell, 2006). A history of severe hepatic or renal impairment, eating disorder or any metabolic condition should be noted, as should significant alcohol or substance misuse. A detailed history of both psychotropic and non-psychotropic drug use will allow clarification of possible pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic interactions (see below).

Clinical investigations

We suggest that patients about to receive higher-risk antipsychotics or those known to have vulnerability should have a baseline electrocardiogram (ECG) before the medication is started. It is also important to consider the ECG recommendations in the data sheets of individual antipsychotics. Biochemical testing may reveal hypokalaemia and hypomagnesaemia, which are risk factors for significant prolongation of the QTc interval. If significant QTc interval prolongation is evident, serum electrolyte and magnesium levels should be measured. A cardiologist's opinion should be obtained if the patient reports recent cardiac ischaemia or significant abnormalities are suspected on an ECG.

Interpretation of the ECG

The QT interval is measured using the trace from lead II or from the lead on which the end of the T-wave is most clearly defined (Reference SchweitzerSchweitzer, 1992; Reference GarsonGarson, 1993). Measurement of the QT interval can be difficult if the T-waves are flat, broad or notched. For example, a notched T-wave could represent fusion of the T-wave and the U-wave. Consequently, machine-generated QTc data may have to be double-checked.

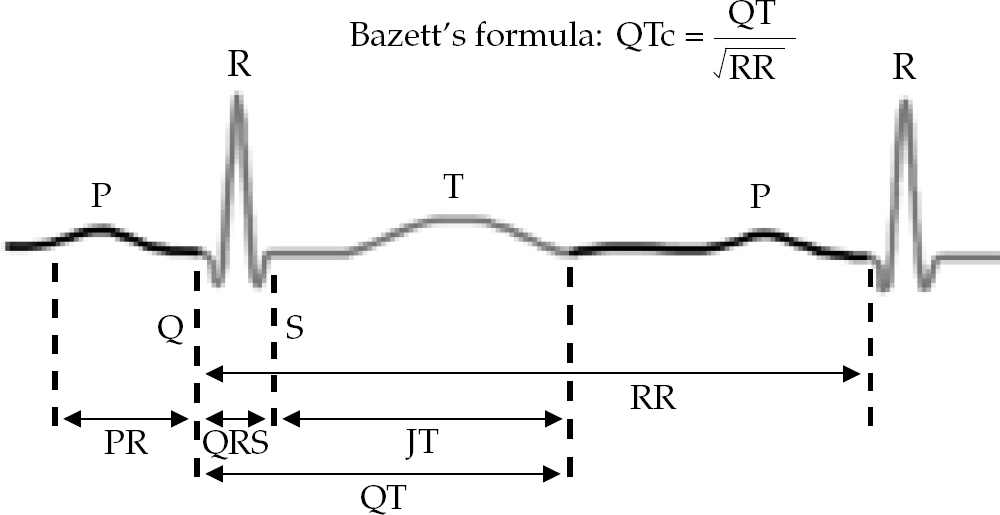

The QT interval should be adjusted for heart rate, which gives the QTc interval. The most commonly used method for this adjustment is Bazett's formula (Fig. 1), which is used in most automated devices (Reference BazettBazett, 1920; Reference Funk-Brentano and JaillonFunk-Brentano & Jaillon, 1993; Reference TaylorTaylor, 2003).

Fig. 1 An ECG trace showing the QT interval.

If the patient is taking medication that affects the QT interval, the time of measurement relative to the time at which the drug was administered may affect the duration of the interval, owing to variation in drug plasma levels. Optimally, the QT interval should be measured within 30–60 min of the peak plasma concentration (Reference Ames, Camm and CookAmes et al, 2002).

If an ECG is difficult to interpret the clinician should consider seeking a cardiologist's opinion.

Testosterone appears to reduce the QT interval, so mean QTc intervals are greater in women than in men after puberty (Reference Rautaharju, Zhou and WongRautaharju et al, 1992). Values generally accepted as indicating normal, short and prolonged QTc intervals vary for men and women, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2 QTc intervals

| Duration, ms | ||

|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | |

| Short | <430 | <440 |

| Borderline | 430 to <450 | 440 to <460 |

| Prolonged | >450 | >460 |

If the patient has a prolonged baseline QTc, it is important to try to avoid all QT-prolonging medications, including high-risk antipsychotics. If the QTc at baseline is short, routine clinical care is acceptable but with the normal cautions regarding non-cardiac adverse effects. There is an area of clinical uncertainty if the baseline ECG reveals a borderline QTc interval (between 430 and 450 ms in men and 440 and 460 ms in women). In such cases a repeat ECG is advised.

The Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products (1997) advises that an increase in QTc of 60 ms or more above the drug-free baseline should raise concern. In cases where the QT interval increases between serial ECGs (QTc variability) enhanced clinical care is indicated. This involves avoiding drugs that could disturb the electrolyte balance or prolong the QT interval further and monitoring of cardiovascular, hepatic and renal function. Most importantly, a switch to a low-risk antipsychotic should be made if assessment of the clinical risks and benefits supports this. We also recommend that the cumulative dose of all antipsychotics received, including as-needed (PRN) medication, be carefully documented in chlorpromazine or haloperidol equivalents.

A QTc interval of 500 ms and above is widely accepted as indicating substantially higher risk of torsade de pointes (Reference BotsteinBotstein, 1993; Reference Welch and ChueWelch & Chue, 2000; Reference Glassman and BiggerGlassman & Bigger, 2001; Reference Malik and CammMalik & Camm, 2001).

Torsade de pointes is a malignant polymorphic ventricular tachyarrhythmia. It can be asymptomatic or it can manifest with dizziness, light headedness, nausea and vomiting, palpitations or syncope. On an ECG, torsade de pointes is characterised by QRS complexes of changing amplitude. It is usually a transient, self-correcting and reversible condition, but occasionally it leads to ventricular fibrillation that presents clinically as a cardiac arrest. About 1 in 10 torsade de pointes events leads to sudden death (Reference Montanez, Ruskin and HebertMontanez et al, 2004).

Torsade de pointes is largely unpredictable, but certain risk factors can be identified (see Part 1 of our overview) that are essentially the same as the risk factors for sudden cardiac death. The management of acute torsade de pointes includes withdrawal of any offending agents, empirical administration of magnesium irrespective of the serum magnesium level, correction of serum potassium to 4.5–5 mEq/l and interventions to increase heart rate (isoprenaline or pacing) if necessary.

Monitoring of physical health

All patients

Various guidelines have appeared on monitoring the physical health of people prescribed antipsychotics (Reference Marder, Essock and MillerMarder et al, 2004; Reference Taylor, Paton and KerwinTaylor et al, 2005). Caridac monitoring must be considered in the context of general health monitoring and, in particular, monitoring for metabolic disturbances.

Physicians should monitor potassium and, ideally, magnesium levels in patients who start QT-prolonging medications (Reference Al-Khatib, Allen LaPointe and KramerAl-Khatib et al, 2003). Hypokalaemia has been associated with many factors, including: diuretics, digoxin and corticosteroids; intensive exercise, wound drainage and burns; and stressful situations (Reference Hatta, Takahashi and NakamuraHatta et al, 1999). Drugs that have the potential to affect electrolyte balance (diuretics, β2 agonists, cisplatin, laxatives and corticosteroids) should be prescribed with caution. Hypomagnesaemia (Box 2) interferes with ventricular repolarisation.

Box 2 Common causes and signs of hypomagnesaemia

Causes

-

• Malnutrition

-

• Crohn's disease

-

• Treatment with diuretics or aminoglycoside antibiotics

-

• Transfusion of blood products preserved with citrate

-

• Alcohol misuse

-

• Hyperglycaemia

-

• Sepsis

-

• Alkalaemia

-

• Clinical signs

Signs

-

• Prolonged QT interval and broadening of the T-wave on ECG

-

• Muscle weakness

-

• Tremors

-

• Vertigo

-

• Ataxia

-

• Chvostek's and Trousseau's signs

-

• Generalised muscle spasticity

-

• Depression

-

• Psychosis

-

• Hypertension

-

• Dysphagia

-

• Anorexia

-

• Nausea

The Committee on Safety of Medicines and the Medicines Control Agency recommend that ECGs and electrolyte measurements be repeated after each dose escalation and at 6-monthly intervals (Medicines Control Agency & Committee on Safety of Medicines, 2001).

Patients with cardiovascular disease

The measures outlined in the previous section apply to all patients taking antipsychotics. Patients with established cardiovascular disease require enhanced monitoring of their physical health. As mentioned earlier, we suggest a minimum of a baseline ECG before they start antipsychotic medication. Routine measurement of weight, blood pressure and heart rate and random glucose tests may be supplemented with measurement of: fasting plasma glucose or haemoglobin A1c; total, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol; and triglyceride levels. Patients with complex cardiac problems, those seen soon after a myocardial infarction and those in heart failure will need joint care with a cardiologist.

Drug interactions

The risk of cardiac arrhythmias and sudden death is not restricted to antipsychotic or even psychotropic drugs. Box 3 lists some other psychotropic and also non-psychotropic medications associated with QT prolongation and potentially serious cardiac arrhythmias. Clinicians are advised to check a standard reference such as the British National Formulary (BNF) for the effect on the QT interval of co-prescribed medications.

Box 3 Drugs associated with QT prolongation

| Antiarrhythmics |

| Almokalant1 |

| Amiodarone |

| Bepridil |

| Bretylium |

| Disopyramide |

| Dofetilide |

| Ibutilide1 |

| Procainamide |

| Propafenone |

| Quinidine |

| Sotalol and d-sotalol1 |

| Antibiotics |

| Clarithromycin |

| Clindamycin |

| Co-trimoxazole |

| Erythromycin |

| Fluconazole |

| Gatifloxacin |

| Levofloxacin |

| Moxifloxacin3 |

| Pentamidine |

| Sparfloxacin3 |

| Spiramycin |

| Antimalaria drugs |

| Chloroquine |

| Halofantrine |

| Mefloquine |

| Quinine |

| Antihistamines |

| Terfenadine3 |

| Astemizole3 |

| Migraine drugs |

| Sumatriptan |

| Zolmitriptan |

| Serotonin antagonists |

| Ketanserin1 |

| Cisapride2 |

| Antipsychotics |

| Thioridazine3 |

| Pimozide3 |

| Ziprasidone1 |

| Sertindole3 |

| Droperidol2 |

| Haloperidol |

| Chlorpromazine |

| Risperidone |

| Olanzapine |

| Antidepressants |

| Amitriptyline |

| Clomipramine |

| Citalopram |

| Desipramine |

| Doxepin |

| Fluoxetine |

| Imipramine |

| Maprotiline |

| Nortriptyline |

| Paroxetine |

| Venlafaxine |

| Other psychotropics |

| Chloral hydrate |

| Lithium |

| Methadone |

| Others |

| Amantadine |

| Cyclosporin |

| Diphenylhydramine |

| Hydroxyzine |

| Tamoxifen |

| Vasopressin |

Polypharmacy, be it with other psychotropic or with non-psychotropic drugs, should be rationalised. If needed, a clear clinical justification should be documented, including discussion with the patient and/or carer, particularly if the combination may result in additive ECG effects.

Polypharmacy is the most important source of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions. Torsade de pointes and QT prolongation have been reported with IKr channel blockers, the antihistamines terfenadine and astemizole, and cisapride (Reference Vitola, Vukanovic and RodenVitola et al, 1998), leading to licensing restrictions or revocation for some (Box 3). These drugs are metabolised by CYP 3A4 of the cytochrome P450 (CYP) system, but this metabolism can be inhibited by certain other drugs, including, for example, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (fluvoxamine, fluoxetine, sertraline) (Tables 3–5). Serious cardiac arrhythmias have been reported in patients taking certain antihistamines with drugs that inhibit CYP 3A4 (Reference Smith, Book, Fuster, Alexander and O'RourkeSmith & Book, 2004). Some women appear to metabolise these drugs slowly, and thus female gender is a risk factor for drug-induced arrhythmia (Reference PrioriPriori, 1998).

Table 3 Antipsychotic drugs and cytochrome P450 metabolising enzymes1

| Cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP 1A2 | CYP 2D6 | CYP 2C9 | CYP 2C19 | CYP 3A4 | |||||

| Substrate | Inhibitor | Substrate | Inhibitor | Substrate | Inhibitor | Substrate | Inhibitor | Substrate | Inhibitor |

| Clozapine Haloperidol |

Thioridazine Haloperidol Chlorpromazine Zuclopenthixol Risperidone Sertindole Clozapine |

Thioridazine Haloperidol |

Clozapine (?) | Risperidone Quetiapine Pimozide |

|||||

Adverse outcomes when drugs are co-prescribed will also depend on whether a drug has a single or multiple metabolic pathways.

Conclusions

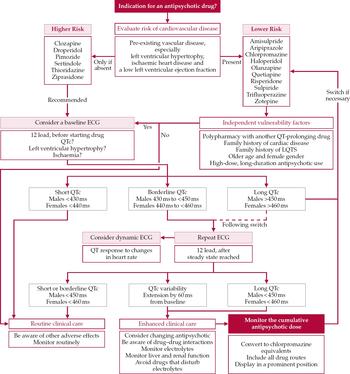

Figure 2 summarises the guidance we have given on monitoring patients prescribed antipsychotics. Psychiatrists should be aware of the possible adverse cardiac effects of these drugs on people with pre-existing cardiac disease or cardiac risk factors. Unfortunately, these are particularly common in people with schizophrenia. In addition, obesity, hyperlipidaemia and glucose intolerance may be exacerbated by antipsychotic drug therapy (Reference Abidi and BhaskaraAbidi & Bhaskara, 2003). This suggests that cardiac safety should be a routine part of clinical care. The advice given here constitutes a preventive strategy that is likely to be worthwhile even if the absolute risk of serious cardiac events is low. Attention should be paid to the general physical health of people with serious mental illnesses, with a full screening for modifiable cardiovascular risk factors.

Fig. 2 Clinician's guide to antipsychotic monitoring in relation to cardiovascular disease.

High-dose prescribing

High-dose prescribing of single or multiple anti-psychotics is a concern that has been previously highlighted. In a US study of people with established schizophrenia treated in the community, Reference Ganguly, Kotzan and MillerGanguly et al(2004) found the prevalence of short-term polypharmacy to be about 40% and of long-term polypharmacy about 25%. However, in a revised consensus statement the Royal College of Psychiatrists suggests that there are some justifiable cases of temporary polypharmacy (such as when changing drugs and in treatment-resistant cases) (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2006). A full discussion of the possible clinical indications for polypharmacy is beyond the scope of this article (see Reference Haw and StubbsHaw & Stubbs, 2003), and we simply point out that there is an additional risk with this strategy and therefore particular care should underlie such treatment decisions.

Drug choice

The choice of antipsychotic is important in determining risk. In Fig. 2 we have grouped antipsychotics into two categories. The use of drugs with more pronounced effects on cardiac repolarisation can be justified only if the drug has specific advantages for the patient. Such risk–benefit decisions can be difficult and, where possible, the patient should be involved in an informed discussion.

Cumulative dosing

Clinicians should be particularly aware that high doses of antipsychotics, often in combination and from multiple prescribers, can accumulate over a number of days or weeks. A national audit of the prescribing of antipsychotic drugs in 47 UK mental health services (Reference Harrington, Lelliott and PatonHarrington et al, 2002) showed that, of 3132 patients, 20% were prescribed a total dose of antipsychotic medication above that recommended by the BNF. In the majority of cases, notes failed to record an indication for high-dose prescribing or that the patient had been informed. Only 8% had undergone an ECG, and 48% were prescribed more than one antipsychotic. A separate audit of drug-prescribing habits showed that polypharmacy was the most likely reason for receiving a high dose (Reference Lelliott, Paton and HarringtonLelliott et al, 2002). Factors that influenced the probability of polypharmacy were younger age, male gender, detention under the Mental Health Act 1983 and a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Clinician-related preferences are also a significant factor in polypharmacy (Reference Wilkie, Preston and WesbyWilkie et al, 2001).

Training needs

One important implication of these issues is the need for training. A survey of junior doctors in psychiatry in the UK demonstrated that less than 20% were able to identify a prolonged QTc interval on an ECG (Reference Warner, Gledhill and ConnellWarner et al, 1996). A more recent survey of healthcare practitioners (including psychiatrists and other physicians) in the USA showed that 61% of respondents could identify the QT interval on an ECG but only 36% correctly measured it (Reference Allen LaPointe, Al-Khatib and KramerAllen LaPointe et al, 2002). Clearly it is impractical to refer every patient to a cardiologist for QT-interval measurement, just as it is inappropriate to expect psychiatrists to measure every person's depressive symptoms. Therefore healthcare professionals involved in the care of people with mental illnesses (in particular psychiatrists and general practitioners) ideally must learn how to measure the QT interval and/or arrange access to an automatic ECG machine. This could form part of the periodic training in cardiopulmonary resuscitation for hospital staff recommended by the Royal College of Psychiatrists (1997).

Several typical and atypical antipsychotics carry a higher than average risk of QTc prolongation and sudden cardiac death. Although the absolute risk is small, appropriate awareness of this risk will help to keep the number of antipsychotic-induced sudden deaths to a minimum.

Declaration of interest

None.

MCQs

-

1 As regards measurement of the QTc interval:

-

a it is less difficult when the T-waves are flat

-

b ideally an ECG should be performed 12 h after the administration of the antipsychotic

-

c the NICE schizophrenia guidelines recommend that ECG and electrolyte tests are repeated after each dose escalation and at 6-monthly intervals

-

d Bazett's correction formula is used in most automated ECG devices

-

e drug-induced extension of the QTc interval to between 450 and 500 ms strongly predicts sudden cardiac death.

-

-

2 Risk factors for torsades de pointes include:

-

a male gender

-

b hypokalaemia

-

c congenital long-QT syndrome

-

d heart failure

-

e hypomagnesaemia.

-

-

3 Modifiable risk factors for developing cardiovascular disease include:

-

a old age

-

b obesity

-

c diabetes

-

d male gender

-

e sedentary lifestyle.

-

-

4 Screening tests for all psychiatric patients considered for an antipsychotic drug should include:

-

a blood pressure measurement

-

b glucose tolerance test

-

c an ECG

-

d an EEG

-

e liver function tests.

-

Table 4 Psychotropics (excluding antipsychotics) and cytochrome P450 metabolising enzymes1

| Cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP 1A2 | CYP 2D6 | CYP 2C9 | CYP 2C19 | CYP 3A4 | |||||

| Substrate | Inhibitor | Substrate | Inhibitor | Substrate | Inhibitor | Substrate | Inhibitor | Substrate | Inhibitor |

| TCAs Maprotiline Fluvoxamine Methadone |

TCAs Fluoxetine Fluvoxamine Mianserin Venlafaxine Maprotiline Bupropion |

TCAs Paroxetine Fluoxetine Norfluoxetine Sertralinel |

Fluoxetine | TCAs Citalopram Moclobemide Diazepam |

Fluvoxamine Fluoxetine Sertraline (?) |

TCAs Sertraline Fluoxetine Venlafaxine Carbamazepine Alprazolam Zolpidem |

Fluvoxamine Fluoxetine Paroxetine Sertraline Nefazodone Venlafaxine Methadone |

||

Table 5 Non-psychotropics and cytochrome P450 metabolising enzymes1

| Cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP 1A2 | CYP 2D6 | CYP 2C9 | CYP 2C19 | CYP 3A4 | |||||

| Substrate | Inhibitor | Substrate | Inhibitor | Substrate | Inhibitor | Substrate | Inhibitor | Substrate | Inhibitor |

| Propranolol Theophylline |

Ciprofloxacin Grapefruit |

Encainide Felainide Codeine Tramadol |

Halofantrine Chloroquine Quinidine Propafenone Beta-blockers |

Diclofenac Ibuprofen Tolbutamide Naproxen Phenytoin Warfarin |

Fluoxetine | Hexabarbital Omeprazole Propranolol |

Omeprazole | Terfenadine Quinidine Diltiazem Midazolam |

Erythromycin Clarithromycin Troleandomy-cin Ketoconazole Itraconazole Cimetidine Indinavir Ritonavir Saquinavir Grapefruit |

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | F | a | F | a | T |

| b | F | b | T | b | T | b | F |

| c | F | c | T | c | T | c | T |

| d | T | d | T | d | F | d | F |

| e | F | e | T | e | T | e | T |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.