It is not uncommon for people with mental illness to be convicted of a criminal offence. The relationship between the two is not necessarily simple. It may be diffuse and subtle, perhaps relating to the disinhibiting effect of severe mental illness or associated factors such as poor social integration, unemployment, lack of close and intimate relationships or substance misuse.

Despite this relationship, it is relatively unusual to combine punishment and medical treatment in sentencing. In most cases, the offender is either punished in a manner proportionate to the crime, or not explicitly punished, being considered in need of medical care and receiving a hospital disposal under the terms of the appropriate Mental Health Act. This has a potential disadvantage in that criminal justice agencies, such as the probation service, may have no further influence in the care of an individual who may be in need of such supervision in addition to psychiatric treatment. There are large numbers of offenders who might benefit from some form of psychiatric or psychological care but who are dealt with solely by way of the criminal justice system. This is an issue for all psychiatrists who are likely to manage mentally disordered offenders (MDOs) and need to be aware of the legislative options available to help them in this task.

There are two ways in which criminal justice measures and medical treatment of an MDO can be combined: the community rehabilitation order, previously known as a probation order; and, in the case of psychopathic disorder, a hospital direction with limitation direction under the Crime (Sentences) Act 1997, otherwise known as the hybrid order. Only eight hybrid orders had been made up to the end of 1999 (personal communication, Home Office, 2001). Probation orders with a condition of psychiatric treatment have been used more frequently but are often viewed with scepticism by psychiatrists and probation officers alike. Consistent calls for their increased use have not been heeded. This paper aims to explain the reasons for this and suggests that, if used correctly in terms of procedure and selection of offender, they can be a useful tool in the supervision and care of a potentially difficult-to-manage group of patients.

Development of probation legislation

The origins of the probation service lie in voluntary missionaries appointed to courts by the Church of England Temperance Society in the second half of the 1800s. The Probation of Offenders Act 1907 formalised supervision and recognised mental illness as a reason for avoiding custodial sentences. Contemporaneous psychiatric treatment was limited to asylum care but, over the ensuing years, as child guidance and adult out-patient clinics gradually developed, conditions of psychiatric treatment began to be included within probation orders (Reference LewisLewis, 1980). This was encompassed in Section 4 of the Criminal Justice Act 1948. Initially, such conditions could last for a maximum of 1 year but the Powers of Criminal Courts Act 1973 allowed the court to impose the additional requirement for such part of the probation order as was considered appropriate, up to a maximum of 3 years. There was further change with the Criminal Justice Act 1991. Probation orders had previously represented an agreement between the court and the offender but now became a sentence in their own right. The establishment of additional requirements of drug and alcohol treatment reinforced the concept of combining treatment with probation. In 1997, the Crime (Sentences) Act removed the requirement for an offender to agree to receive a probation order. However, some additional requirements must still be agreed, one being the imposition of a condition of psychiatric treatment.

Historical perspective on use and previous research

Following their introduction in 1948, there was a steep rise in the number of psychiatric probation orders made each year. It may be assumed that they were seen as a useful tool by psychiatrists, courts and the probation service alike. One of the earliest pieces of published research in this area was a follow-up study of all orders made in 1953 (Reference GrunhutGrunhut, 1963). Grunhut emphasised the importance of the type of crime in identifying individuals who might be appropriate for probation with a condition of psychiatric treatment. Such crimes included shoplifting ‘for negligible advantage’ by women, repetitive minor offences committed over long periods that had an ‘almost obsessional character’ and sexual offences, particularly indecent exposure and ‘homosexual crimes’. Of 97 offences against the person, 65 were attempted suicide, an offence abolished by the Suicide Act 1961. In Grunhut's study, nearly half of the sample had received a diagnosis of psychopathic personality disorder, with schizophrenia and depression the next most common diagnoses.

Grunhut concluded that the orders were broadly successful in terms of reducing reoffending, but noted that recidivism was more likely if a probationer had a psychiatric report prepared by someone other than his or her supervising clinician. He commented on the need for improved collaboration between psychiatrists and probation officers. He also suggested that the orders were underused and that large numbers of suitable offenders were receiving alternative sentences, perhaps with reduced effectiveness.

Woodside (1971) presented a more pessimistic picture. In keeping with Grunhut, she also found that personality disorder was the most common diagnosis, representing almost half the sample described. Mental deficiency ranked second. She noted that only a small fraction of the sample was considered by psychiatrists and probation officers to have fared well and that the rate of failure to attend out-patient appointments was extremely high. She suggested that the apparent motivation for treatment at the time of sentencing was transient. Woodside also commented on the lack of understanding that psychiatrists appeared to have of the role of the probation service and the frequent breakdown in communication between agencies.

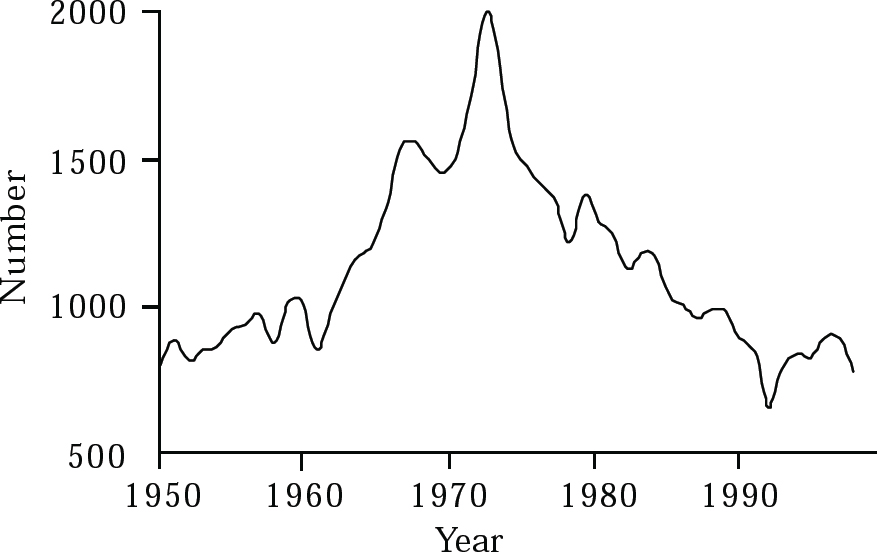

In 1975, the Butler Committee (Home Office & Department of Health and Social Security, 1975) presented the view that there should be a more frequent use of an additional requirement of psychiatric treatment by the courts. It also noted that probation officers ‘should work in conjunction with the doctor in carrying out the treatment plan’. The Committee suggested that the two forms of supervision, medical and probation, should be complementary, each potentiating the positive effects of the other. They rejected a recommendation from the Chief Probation Officer that there should be part-time consultant psychiatrists working within the probation service, on the grounds that there were too few with the necessary experience. The introduction of the Powers of Criminal Courts Act 1973 should also have encouraged the use of more psychiatric probation orders. However, 1973 represented a peak in their use, which was followed by a sharp and sustained decline (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Annual numbers of probation orders with conditions of psychiatric treatment in England and Wales, 1950–1999 (data from Edwards, 1982, and the Home Office, 2000a)

Subsequent research pointed to the difficulties in effective collaboration between health and probation services but failed to suggest solutions. Bowden (1978) described an attempt to set up a psychiatric clinic in a probation office that housed 41 probation officers. In a year of weekly clinics he had 23 referrals, too few to justify continuing the initiative. He commented on the caution with which both the hospital and probation officers approached the project, citing concerns over confidentiality and compromise of professional status. In a descriptive study of psychiatric probation orders in Nottinghamshire, Lewis (1980) emphasised the importance of communication between the psychiatrist and the probation officer at the time of report writing. He found that this was often inadequate and that reports rarely included any detail about the treatment or professional input that was proposed. The agencies had little understanding of each other's roles and failed to communicate, even after the order was made. Similarly, Gibbens et al (1981) described a sample from London and Wessex, nearly one-fifth of whom never received any treatment subsequent to sentencing. According to the treating doctors, only 5% were much improved at the end of the order. Probation officers estimated that 9% were much improved. Despite this, these authors concluded: ‘what is beyond question is that the total number of probation orders with conditions of treatment is much too small’. In 1992, the Reed Report (Department of Health & Home Office, 1992) concluded that ‘probation orders with conditions of psychiatric treatment should be considered more frequently’.

The contemporary context

An explanation is needed of this discrepancy between the perceived value of psychiatric probation orders to expert committees and researchers and their apparent perceived ineffectiveness on the part of psychiatrists and probation officers, which is manifest in their pattern of use. Some of the findings of previous research are likely to be of limited relevance today, having been overtaken by changes in psychiatric care, treatment and priorities. The diagnostic patterns noted by Grunhut (1963) and Woodside (1971), with personality disorder being found most commonly, are likely to have changed. Previous therapeutic optimism with regard to patients with personality disorder has waned so that psychiatrists are probably now less likely to recommend additional requirements of psychiatric treatment in such cases. There is some evidence for this in contemporary research. For example, Clark et al (2002) have described a sample of probationers resident in a specialist bail and probation hostel for MDOs, over two-thirds of whom had a psychotic illness. It might be expected that patients with personality disorder would fare less well than those with mental illness alone. It is also likely that, only partly as a consequence of changes in selection of patients, psychotherapy has been replaced by pharmacotherapy as the most commonly employed treatment (Reference GrunhutGrunhut, 1963).

Other observations probably remain important. Woodside's (1971) suggestion that motivation for treatment is transient is unsurprising. Her observed falling rates of attendance at out-patient appointments may be a reflection of the same phenomenon that occurs in attendance at probation appointments.

Recently, the Minister for Prisons and Probation said of the probation service ‘We are a law enforcement agency. It's what we are. It's what we do’ (Home Office, 2000b ). This is in contrast to the origins of the service in voluntary missionary organisations providing care and support. There may be parallels between this potential conflict within the probation service and the tension between treatment of illness and risk management experienced in psychiatry. Both agencies are subjected to similarly conflicting socio-political pressures. This may contribute to the poor liaison and collaboration between agencies that has been described in previous research, making mutual understanding and distinction of roles more difficult. There is no evidence to suggest that collaboration has generally improved of late, although, encouragingly, isolated pockets of effective collaborative working have recently been described (Reference Geelan, Griffin and BriscoeGeelan et al, 2000; Reference Nadkarni, Chipchase and FraserNadkarni et al, 2000; Reference Clark, Kenney-Herbert and BakerClark et al, 2002). It is noteworthy that Grunhut (1963) demonstrated an increased rate of recidivism if the pre-sentence psychiatric report was prepared by someone other than the supervising psychiatrist. It is possible that this is a reflection of the characteristics of those probationers who had their reports prepared by prison doctors while remanded in custody. It may also be that it reflects a lack of planning of future care for those patients and the importance of this for a psychiatric probation order to succeed.

Collaborative planning of care requires an understanding of the roles and expectations of other professions. Harding & Cameron (1999) called for improvements on behalf of the probation service and unwittingly illustrated the difficulties involved. They defined MDOs as people ‘who are thought to have problems generally regarded as psychiatric or psychological’ (p. 466). Mental health professionals may not agree with this definition. It is probably too broad to discriminate between those offenders who are in need of psychiatric care and those who are not. It does, however, illustrate the importance of this issue. The difficulty in reaching an agreement even over which offenders are appropriate for this form of supervision is likely to promote disagreement between disciplines and compromise their ability to work usefully together.

The group of probationers described by Clark et al (2002) were young, male, single and unemployed, with a history of polysubstance misuse and heterogeneous offending as well as a severe mental illness and a tendency to poor compliance with psychiatric follow-up. If such a group of patients is to be treated successfully, it seems clear that their care must be effectively managed. This necessitates a close relationship between the various agencies involved. The absence of this in the past may have been the primary reason for the demonstrated lack of enthusiasm for community rehabilitation orders with conditions of psychiatric treatment. This is not a new suggestion. Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Probation (1993) previously noted the widespread occurrence of poor reciprocal understanding of respective roles but commented that ‘where there has been good co-operation between the medical and probation services, the making of a requirement for treatment ensures that well planned multidisciplinary arrangements are brought into play’ (pp. 36–37).

Current legal provision

The legislative framework for probation orders requiring treatment for mental condition was set out in Section 3 of the Powers of Criminal Courts Act 1973, which was substituted and amended by Section 9 and Schedule 1 of the Criminal Justice Act 1991 (see Box 1).

A duly qualified medical practitioner is defined as one who is approved for the purposes of Section 12(2) of the Mental Health Act (MHA) 1983. Therefore, general practitioners and non-consultant grade doctors, as well as consultant psychiatrists, may give evidence to the court and may supervise subsequent treatment. The legislation allows for the supervising doctor to be changed during the course of the order. Special hospitals are excluded from the definition of mental hospital, which does, however, include mental nursing homes within the meaning of the Registered Homes Act 1984.

Mental condition is not defined further. It may be different from the ‘mental disorder’ or ‘mental illness’ of the MHA, and is presumably a matter for clinical judgement. The Criminal Justice Act 1991 provided an opportunity for adjustment of terms so as to preserve a common and transparent meaning, but this chance was not taken.

Box 1 The Criminal Justice Act 1991

Schedule 1 of the Act states that:

‘Where a court … is satisfied on the evidence of a duly qualified medical practitioner that the mental condition of an offender: (a) is such as requires and may be susceptible to treatment; but (b) is not such as to warrant the making of a hospital order or guardian ship order … the probation order may include a requirement that the offender shall submit … to treatment by or under the direction of a duly qualified medical practitioner with a view to the improvement of the offender's mental condition.

‘The treatment … shall be one of the following kinds of treatment as may be specified in the order … (a) treatment as a resident patient in a mental hospital; (b) treatment as a non-resident patient at such institution or place as may be specified; (c) treatment by or under the direction of such duly qualified medical practitioner as may be so specified… The nature of the treatment shall not be specified in the order except as mentioned … above.’

The three types of additional requirement are worthy of further thought. The wording (Box 1) seems to suggest that a community rehabilitation order with an additional requirement of psychiatric treatment is appropriate only where the mental condition of the offender is not such as to warrant a hospital order. In other words, the offender does not suffer from a mental disorder ‘of a nature or degree which makes it appropriate for him to be detained in hospital’ (MHA 1983, Section 37). It is unclear under what circumstances an additional requirement of mental treatment as a resident patient in a mental hospital would be appropriate. This is, in fact, by far the least commonly used additional requirement, as shown in Table 1. Treatment under the direction of a duly qualified medical practitioner seems to overlap with the other two forms. The legislation makes no further distinction between them. There has been no investigation of the determinants of psychiatric recommendations or the decision-making processes of the courts. It may be that the sub-type of condition imposed is determined by individual preferences of particular psychiatrists or courts.

Table 1 Psychiatric community rehabilitation orders by category of additional requirement, England and Wales 1999 (Home Office, 2000a )

| Order | Number |

|---|---|

| Non-residential mental treatment | 506 |

| Residential mental treatment | 50 |

| Mental treatment by or under | |

| qualified medical person | 257 |

| Total | 813 |

Section 5 of Schedule 1 of the Criminal Justice Act 1991 repeats a controversial Section of the Powers of Criminal Courts Act 1973. This states that:

‘while the offender is under treatment as a resident patient, … the probation officer … shall carry out supervision to such extent only as may be necessary for the purpose of the revocation or amendment of the order.’

This is unfortunate in the light of the previous research findings of inadequate liaison and collaborative working between psychiatry and probation services. It was criticised by the Butler Committee in 1975, which said that it would ‘support the view that probation officers need to have continuously close involvement while their clients are in hospital’ (Home Office & Department of Health and Social Security, 1975).

Finally, before making the order, the court must be ‘satisfied that arrangements for treatment are in place’ (Schedule 1, Section 4). Gibbens et al's (1981) finding that nearly one-fifth of their sample never received any treatment suggests that, at least at that time and for those people, the arrangements were not in place. It is more difficult to know whether the courts failed to ensure that they were satisfied on this point, or whether the lack of treatment in so many cases was entirely unforeseeable.

Community rehabilitation orders in practice

The community rehabilitation order is one of three community sentences available to the courts. The terminology has changed recently. Probation orders have become community rehabilitation orders; community service orders have become community punishment orders; and the combination order is now known as the community punishment and rehabilitation order.

The requirements of supervision by the probation service are set out in the National Standards for the Supervision of Offenders in the Community (Home Office, 2000b ). The purposes of a community sentence and the issues that must be addressed in the written supervision plan are shown in Box 2.

Box 2 National Standards for the Supervision of Offenders in the Community 2000 (Home Office, 2000b )

The purposes of a community sentence are to:

-

• provide a rigorous and effective punishment

-

• reduce the likelihood of reoffending

-

• rehabilitate the offender where possible

-

• enable reparation to be made to the community

Required components of a supervision plan are:

-

• the risk that offenders may cause serious harm to others

-

• the causes and patterns of offending

-

• offence-related needs and circumstances

-

• the offender's motivation to change their behaviour

-

• the offender's health, skills, availability to work, religion and culture

The Standards also name a number of other issues that may be applicable to individual cases and should be included where appropriate. Mental illness does not feature explicitly in the list, but when present it is likely to be of importance in terms of the statutory considerations.

It is usual for the period of supervision to begin with a series of 12 appointments at weekly intervals, subsequently reducing in frequency to a minimum of once a month for the duration of the order.

Any failure to comply, if not accompanied by a satisfactory explanation, must result in a warning or breach proceedings. Only one warning is permitted within any 12-month period. On the second ‘unacceptable failure to comply’, breach proceedings must be started. A failure to comply may relate to any required aspect of the community rehabilitation order, including, for example, attendance for psychiatric out-patient appointments. If, in a particular case, it is considered that the individual is not able to comply, whether through mental illness or some other factor, the national standards may be suspended. This can be done in advance of, or following, a failure to comply, but the decision must be reviewed every 3 months. It is likely that if such a consideration is required with respect to a probationer who has additional requirements of psychiatric treatment, the psychiatrist will wish to be involved in the decision-making process.

If a probationer is considered to be in breach of a community rehabilitation order, he or she is returned to court, where he or she may plead to the breach. The court has three options for disposal. The order may be revoked and the probationer re-sentenced for the original offence; the order may be continued and a further punishment (such as a fine) added; or the order may be continued with no further sanction. The experience of returning to court may act as a warning and improve compliance in the future.

If, while serving a community rehabilitation order, a further offence is committed, there are no immediate consequences for the order, which continues. The offender will be dealt with in the usual way and, if found guilty, may have a further community sentence added that runs alongside the original order. If a custodial sentence is imposed, it is likely that the community rehabilitation order will be revoked. In some cases, where the prison sentence is short, the order may remain in place and provide a period of supervision on release from custody.

Suggestions for improved use

Agreement of roles and identification of MDOs

If psychiatry and the probation service are to work effectively together, they need to decide on the specific roles that each will play in the management of MDOs. This is more important than striving to find a definition of the appropriate individual. Such an elusive definition is unlikely to help in discussions about those who have a combination of mental illness, personality disorder and substance misuse. The selection of offenders for community sentences is made by the probation service. The appropriateness of additional requirements of psychiatric treatment is determined by psychiatrists. Each should understand the reasoning of the other. Psychiatrists need to accept responsibility for the appropriate part of the problem in a pragmatic and collaborative way, but they must also be clear about the limits of their skills and responsibilities.

Once roles are determined and understood by the two agencies, and areas of overlap and divergence are acknowledged, it will become easier to recognise and agree upon the most appropriate patients. It may also become clear that there are gaps that need to be filled in some other way, such as by referral to psychology or other services. We suggest that the following three are important issues to consider.

Is the mental condition susceptible to treatment?

The legislation requires that the ‘mental condition … may be susceptible to treatment’. This is a concept that is liable to cause disagreement among psychiatrists. The possibility of further offending may, in some cases, lead to a reluctance on the part of psychiatrists to become involved in a criminal justice system sanction, especially if the offender's mental condition is one that might not respond to treatment. Others will see a legitimate role for psychiatry in the management of offenders with ‘untreatable’ personality disorder, or sex offenders with no mental illness. Regardless of these difficulties, it will be necessary for the psychiatrist involved to be clear about what he or she considers to be treatment and where his or her responsibilities end. The opportunity to agree this with the probation service at the time of considering a psychiatric community rehabilitation order may be helpful for psychiatrists who increasingly feel the burden of public protection threatening the primacy of therapeutics.

Will psychiatric treatment aid probation supervision, as a consequence of improvements in the mental health of the probationer?

A patient may be too ill to be able to work effectively with the probation service to address his or her offending behaviour. Psychiatric treatment may play a vital part in improving mental health such that probation work is possible.

Will probation supervision aid psychiatric treatment?

In some cases, an offender may already have a history of poor compliance with psychiatric treatment, which has prevented a sustained improvement in health from being achieved. For some, the increased structure and supervision of a community rehabilitation order, together with the possibility of further sanctions through the criminal justice system, may improve compliance with treatment.

Inter-agency liaison before sentencing

When the pre-sentence report is prepared by the probation officer and the psychiatric report is written, there should be a discussion of the issues relating to the case. The essential issues to consider and the requirements for the psychiatric report are shown in Box 3.

Box 3 Issues to consider prior to sentencing

Does the patient have a mental condition that may be amenable to treatment?

Is probation supervision likely to aid psychiatric treatment, or is psychiatric treatment likely to aid probation supervision?

What roles would the probation officer and the psychiatrist play in this particular case?

What will be the problems in supervising and treating this offender?

Can failures to comply be predicted and what action should be taken if they occur?

Within the psychiatric report the psychiatrist needs explicitly to state:

-

• that the offender has a mental condition

-

• that requires and may be susceptible to treatment

-

• that the mental condition is not such as to warrant a hospital order

-

• whether treatment should be as a resident patient, a non-resident patient or under the direction of a qualified medical practitioner

-

• a description of the arrangements made for treatment such that the court can reasonably be satisfied that this treatment will occur

Collaboration during supervision

Regular contact must be maintained between professionals throughout the supervision period to ensure that each is aware of the actions of the other. This would improve the support available to the probationer and also communicate a sense of structure that might aid motivation and compliance. Joint appointments should be considered.

Incidents of failure to comply must be communicated promptly and the appropriate sanction discussed. If breach proceedings are instituted, the psychiatrist would expect to be informed so that he or she has a chance to give his or her view to the court through the probation officer. In the event of early termination of supervision following further offending, it will be necessary for the psychiatrist to be able to ensure that some form of alternative contact and follow-up is available.

Future changes

It might be argued that the current legislative criteria for community rehabilitation orders with a requirement for psychiatric treatment require review. The suggestion that probation officers need not be closely involved in supervision while an offender is in hospital is flawed. A period of in-patient treatment represents a valuable opportunity to build bridges, foster understanding and develop a common goal with discriminated tasks.

There is confusion over the three types of additional requirement. It is unclear why non-residential treatment should be more appropriate than treatment by a qualified medical practitioner or why, if in-patient treatment is necessary, residential treatment is more appropriate than a hospital order. A single additional requirement could suffice. Provision for flexibility of location of treatment and for varying the supervising doctor could be included.

The relationship between the probation service and mental health teams needs further consideration. It should be closer, with routine contact in the management of patients who are subject to probation supervision. Harding & Cameron (1999) called for a psychiatric contribution to the training of probation officers. This would be beneficial. There are further levels of potential collaboration. Mental health teams could associate themselves with a specific probation officer to improve the efficacy of link-working in relevant cases. This would promote a reciprocal understanding of roles, improve inter-agency communication and enable more effective joint working.

The community rehabilitation order with an additional requirement of psychiatric treatment is the closest thing to a community treatment order currently available to psychiatrists. The latter is controversial but was considered as one part of the proposals in relation to reform of current mental health legislation. It is unfortunate that for more than 50 years since its introduction, the psychiatric probation order has been used so infrequently and ineffectively. It may be that if used appropriately, it could be a useful tool to aid in the management of a particularly difficult-to-engage group of patients.

Multiple choice questions

-

1. The probation order is now known as a:

-

a community punishment order

-

b community rehabilitation order

-

c community supervision order

-

d community punishment and rehabilitation order

-

e community sentence.

-

-

2. The psychiatric evidence to the court should:

-

a confirm that the offender suffers from a mental condition

-

b satisfy the court that arrangements for treatment are in place

-

c confirm that the mental condition of the offender requires and may be susceptible to treatment

-

d specify the medication or psychological treatment intended

-

e specify whether treatment should be as a resident patient, non-resident patient or name the psychiatrists willing to take responsibility for treatment.

-

-

3. If a probationer reoffends during the course of a probationer order:

-

a the community order terminates automatically

-

b the probationer may be re-sentenced for the original offence in addition to the new one

-

c the offender may be sentenced for the new offence and the probation order continued

-

d the probation order must be terminated if a custodial sentence is imposed

-

e a further probation order may be given in addition to the current one.

-

-

4. Which of the following statements are correct?

-

a in most cases, breach proceedings must be started if more than two warnings occur in any 12 month period

-

b if a probationer has a mental illness, the national standards for probation supervision must be set aside

-

c the Criminal Justice Act 1991 redefined mental condition as being analogous to mental disorder in the Mental Health Act 1983

-

d an offender has to agree to the imposition of additional requirements of psychiatric treatment

-

e failure to attend a psychiatric out-patient appointment is not sufficient to be considered an unacceptable failure to comply.

-

-

5. In the Powers of Criminal Courts Act 1973, a mental hospital may be:

-

a a mental nursing home

-

b an open psychiatric hospital

-

c a psychiatric hospital with locked facilities

-

d a medium secure psychiatric hospital

-

e a special hospital.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | T | a | F | a | F | a | F |

| b | T | b | T | b | T | b | F | b | T |

| c | F | c | F | c | T | c | F | c | T |

| d | F | d | F | d | F | d | T | d | F |

| e | T | e | T | e | T | e | T | e | F |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.