Men and depression is a complicated and contentious issue and many will even disagree about whether clinicians should concern themselves with it, because the prevalence of depression is greater in women. Although the work of the mythopoetic men's movement in using fairy tales such as Iron John (Reference BlyBly, 1990) to explore archetypes of gender, for example, may be overzealous and naive, it does not mean that we have to be equally overzealous in ignoring men with mental health issues. Despite the greater prevalence of depression in women, there are three important reasons for exploring depression in men.

First, even if men represent a numerical minority group among patients with depression they still require effective interventions. Second, although healthcare services find that they are diagnosing and treating many more women with depression than men, community surveys suggest that this disparity is disproportionate. In the UK, for example, figures from general practice for 1994–1998 show a male:female ratio of 0.4:1.0 for depression (Office of National Statistics, 2000), and data from a national household survey in 2000 show a ratio of 0.8:1.0 for depressive episode and disorders (Reference Singleton, Bumpstead and O'BrienSingleton et al, 2000). The greater prevalence of depression in women might, for example, be an artefact of how depression is recognised and treated or of how men self-diagnose and seek help. Third, mental health issues such as alcohol dependency (Alcohol Concern, 2005) or being subject to compulsory detainment and treatment (Healthcare Commission, 2007), which predominantly involve men, might be related to emotional distress and depression. Worldwide, the rate of suicide mortality for men is four times higher than that for women (Reference White and HolmesWhite & Holmes, 2006) – China is the only country where women's suicide mortality is greater than men's (Reference HawtonHawton, 2000) – and research by Reference Möller-LeimkühlerMöller-Leimkühler (2003) argues that suicide is linked to depression in men.

Current approaches to men and depression draw on theories of sex differences, gender roles and hegemonic masculinity explored in this article.

Sex differences: ‘male’ depression

When introducing sex differences it is important to define the term ‘sex’ and its relation to the term ‘gender’. However, providing definitions is difficult because the research that we have drawn on here uses these terms in different ways. It is therefore perhaps better to outline the general approaches to these terms. Broadly, ‘gender’ denotes the sexual distinction between male and female that is an amalgamation of biological, cultural, historical, psychological and social factors, although the word is often used deliberately to exclude biological factors. In terms of gender, ‘sex’ refers to just those biological factors that distinguish male and female, and ‘sex differences’ are factors (biological, cultural, etc.) related to sex. It is important to emphasise that a sex difference is not necessarily biological, although it does rest on an assumed common understanding of a biological distinction between men and women.

Establishing sex difference in research is simple and powerful (perhaps because of its simplicity), particularly in depression. As with epidemiological studies on depression, more specific studies on symptoms have found that women experience more symptoms of depression than men but that there are no sex differences in the quality of symptoms. A 15-year prospective community study found no sex differences in the number or duration of depressive episodes but, importantly, women reported more symptoms per episode (Reference Wilhelm, Parker and AsghariWilhelm et al, 1998). In clinical samples, however, sex differences in the number of symptoms are less marked and show similar functional impairment and global severity (Reference Young, Scheftner and FawcettYoung et al, 1990), but women are more likely to have a history of treatment for depression (Reference Kornstein, Schatzber and ThaseKornstein et al, 2000).

The reduction in sex differences from community to clinical samples seems to suggest that diagnostic procedures or self-care practices are resulting in a population of depression that is not representative. More specifically, there might be underdiagnosis of men, overdiagnosis of women, or systematic misdiagnoses of both men and women, which could be explored by looking at what happens in routine clinical practice. It is interesting to note that where studies have found a symptom to occur more frequently in one sex, it is the symptoms for women that appear in diagnostic criteria. In depressed women, symptoms that have been found to occur more frequently are worry, crying spells, helplessness, loneliness, suicidal ideas (Reference Kivelä and PahkalaKivelä & Pahkala, 1988), augmented appetite and weight gain (Reference Young, Scheftner and FawcettYoung et al, 1990). Non-diagnostic symptoms found more frequently in depressed women are bodily pains and stooping posture (Reference Kivelä and PahkalaKivelä & Pahkala, 1988). However, symptoms that have been shown to occur more frequently in depressed men are slow movements, scarcity of gestures and slow speech (Reference Kivelä and PahkalaKivelä & Pahkala, 1988), non-verbal hostility (Reference Katz, Wetzler and CloitreKatz et al, 1993), trait hostility (Reference Fava, Nolan and KradinFava et al, 1995) and alcohol dependence during difficult times (Reference Angst, Gamma and GastparAngst et al, 2002), which are not common to diagnostic criteria for (adult) depression. Increased hostility might be indicative of a conduct disorder mixed with depression (ICD–10 F92.0; World Health Organization, 1992), but is limited to onset in early childhood. International diagnostic criteria and non-diagnostic symptoms for depression are listed in Box 1, with footnotes showing which symptoms the sex differences research shows to be more prevalent in men or women. These criteria may not be entirely representative of contemporary mental health practice – for example, aggression may be recognised as part of adult depression by many practitioners – but the list at least provides a useful summary of this body of research.

Box 1 Diagnostic criteria and non-diagnostic symptoms for depression

ICD–10 F32 Depressive episode (World Health Organization, 1992)

-

• Depressed mood

-

• Loss of interest or enjoyment

-

• Reduced energy, leading to increased fatiguability and diminished activity

-

• Marked tiredness after slight effort

-

• Reduced concentration and attention

-

• Reduced self-esteem and self-confidenceFootnote 1

-

• Ideas of guilt and unworthiness

-

• Bleak and pessimistic views of the future

-

• Ideas or acts of self-harm or suicideFootnote 1

-

• Disturbed sleep

-

• Diminished appetiteFootnote 1

DSM–IV Major depressive episode (American Psychiatric Association, 1994)

-

• Depressed mood

-

• Loss of interest or enjoyment

-

• Weight loss

-

• Insomnia or hypersomnia

-

• Psychomotor agitation

-

• Fatigue

-

• Feelings of unworthinessFootnote 1

-

• Reduced concentration

-

• Slow movementsFootnote 2

-

• Slow speechFootnote 2

Non-diagnostic symptoms

-

• Alcohol dependence during difficult timesFootnote 2

-

• Bodily painsFootnote 1

-

• Hostility (non-verbal)Footnote 2

-

• Hostility (trait)Footnote 2

-

• Scarcity of guesturesFootnote 2

-

• Stooping postureFootnote 1

Although differences in symptom presentation may be explained as different behavioural patterns of depression or dimensions of distress, it is not entirely implausible that there might exist a form of depression that has hitherto remained absent from international diagnostic criteria. Indeed, this possibility has led some to theorise a ‘male depressive syndrome’ (Reference Rutz, von Knorring and PihlgrenRutz et al, 1995; Reference van Praggvan Pragg, 1996) that is characterised by sudden and periodic irritability, anger attacks, aggressive behaviour and alexithymia. The Gotland Scale of Male Depression (Reference Zierau, Billie and RutzZierau et al, 2002) has been developed with such a syndrome in mind. In an out-patient clinic for alcohol dependency, standard diagnostic criteria identified major depression in 17% of male patients, whereas the Gotland Scale found depression in 39%. In a clinical sample, the Gotland Scale could find no gender differences (Reference Möller-Leimkühler, Bottlender and StraußMöller-Leimkühler et al, 2004). However, the Gotland Scale looks for signs that are not usually understood as symptomatic of depression so it is not surprising that there is little difference between men and women diagnosed with depression using this scale. Nevertheless, in the clinical sample there was a greater intercorrelation of symptoms of male depression in men, which is something that could be explored in community samples. This scale, when utilised in a study of 607 new fathers, identified a prevalence of 6.5% suffering what could be classed as post-natal depression and of these, 20.6% were not identified by the use of the Edinburgh Post Natal Depression Scale alone (Reference Madsen and JuhlMadsen & Juhl, 2007).

The sex differences approach to depression in men has the potential to provide the diagnostic tools to allow psychiatric services and clinicians to recognise and treat a new form of (male) depression. Nevertheless, it is unclear how such an approach might be used to inform treatment, for example whether antidepressants will be appropriate or effective. In addition, focusing on sex differences can mean that differences between men, such as socio-economic status, are ignored.

Gender roles – ‘masked depression’

Gender role theory sees gender in terms of the cultural and historical ways in which biological sex differences are played out at the individual and social level. As cultural constructs, gender roles rarely provide an accurate description of any individual man or woman; rather, they are social lenses (Reference BemBem, 1993) through which men and women perceive themselves and each other. Roles are learnt through processes of socialisation – such as modelling (copying) one's parents – which means that gender roles self-perpetuate and come to constitute material reality. For example, family law often deals with cases of child abuse and domestic violence, and requires its legal professionals and their clients to deal unemotionally with the facts of the case – no matter how upsetting these may be (Reference Pond and MorganPond & Morgan, 2005). Successful professionals are those that can negotiate the system by the use of reason while keeping any sentiment private, which proliferates a particular way of being a professional. This creates what we might call the ‘role’ of a legal professional and illustrates how aspects of that role may be learnt (e.g. through rewarding professionals that stick to the facts) as a function of the structure (such as the ‘factual’ requirements of evidence in court) in which the role is enacted. Presumably, given the right context anyone can enact any role, which means that men can enact male and female roles, and women can enact female and male roles. Epidemiological sex differences in the symptoms of depression may be evidence not of a different type of depression but of ways of expressing or coping with depression that are appropriate to a particular gender role.

The male and female roles are understood as norms that individuals aspire to and enact differently. An individual can adhere strictly to one role (masculine or feminine), weakly to both roles (androgynous), strongly to both (undifferentiated) or to neither (ambiguous). Although the definition of a particular role may be culturally dependent we can presume that because gender roles are self-perpetuating through processes of socialisation they are rarely subject to substantial change. For issues of mental health and illness the coping style of each gender role is particularly apt. In gender role theory, the feminine style of coping is to deal with the emotion associated with the stressor (emotion focused), whereas the masculine style is to deal directly with the stressor (problem focused) (Reference Li, DiGiuseppe and FrohLi et al, 2006). Feminine, emotion-focused coping is associated with higher levels of depression than masculine problem-focused coping (Reference Compas, Malcarne and FondacaroCompas et al, 1988; Reference Ebata and MoosEbata & Moos, 1991). However, the research on sex differences mentioned above suggests that diagnostic criteria fail to include a male depressive syndrome, which may mean that depressive symptoms in masculine, problem-focused individuals have remained hidden. Indeed, Reference Good and WoodGood & Wood (1995) point out that the masculine role is antithetical to recognising and expressing depression and to utilising emotion-focused interventions such as psychotherapy. For example, seeking help might be interpreted as incompetence and dependence (Reference Möller-LeimkühlerMöller-Leimkühler, 2002), and research has shown that individuals who adhere to the masculine role have negative attitudes towards using counselling services (Reference Good and WoodGood & Wood, 1995). This has led some to theorise a disorder of masked depression, where the reduced affect is, for example, manifest in physical symptoms (Reference Kielholz and KielholzKielholz, 1973). Interestingly, associating masculinity with mental ill health has been important for the antisexist men's movement (e.g. the male role leads men to be violent to women) and for an antifeminist backlash (e.g. the male role damages men and privileges women), and this has been taken up in gender role theory with little recourse to empirical evidence. Regardless of whether masculine individuals are more likely to experience depression it is important to note that if they do, it seems that they will be less likely to recognise it as depression and to seek help.

The gender role theory approach to men and depression suggests that services could be redesigned to target masculine, problem-focused individuals. In addition, services could adopt practices to help men with depression challenge gender role norms, which would theoretically leave them better able to recognise and accept help for their own depression. Although gender role theory does acknowledge possible differences between men, it relies on a fundamental opposition between male and female. This risks overemphasising gender when other factors, such as class and ethnicity, may be more important. In particular, gender role theory largely focuses on women or, when focusing on men, is based on affluent White US college students, who are unlikely to reflect the diversity of men with depression.

The list of gender role characteristics shown in Table 1, predominantly from the 1970s, may seem dated and difficult to take seriously. However, the point is that if we cannot take historical gender role characteristics seriously then current gender role research may suffer the same fate. Indeed, a review (Reference Choi and FaquaChoi & Faqua, 2003) of factor analytic studies validating the definitive gender role psychometric measure – the Bem Sex Role Inventory (BSRI; Reference BemBem, 1974) – suggests that the understanding of masculinity and femininity in gender role theory is insufficiently complex. Another difficulty with gender role theory is that it seems to conceptually confuse gender norms with an individual's behaviour, which could result in potentially unhealthy male role norms being seen as ‘normal’ things for men to do.

Table 1 Gender role characteristics1

| Masculine | Feminine | Neutral |

|---|---|---|

| Leader | Childlike | Adaptable |

| Aggressive | Gentle | Conceited |

| Ambitious | Gullible | Helpful |

| Athletic | Loyal | Inefficient |

| Decisive | Tender | Moody |

| Independent | Yielding | Unpredictable |

Hegemonic masculinity – ‘depression enacting gender’

Reference ConnellConnell's (1987) concept of hegemonic masculinity is perhaps the most popular approach to gender in academia at present. Like gender role theory, hegemonic masculinity focuses on the social, rather than biological, aspects of gender. Gender is understood as something that is actually done by people. Thus, if men regularly do something in a certain way – such as waking early, being last to leave work, working at home in the evening – and this is accepted by both men and women it becomes a masculine feature, a masculinity. Gender is multiple, as practices may construct many ways of being a man, and historical, as these ways of being a man change. Power is particularly important: ‘hegemony’ refers to insidious processes of domination where the majority of people come to believe that particular ideas are not only natural but are for their benefit. Different masculinities must therefore compete to define what it is to be a man, and the dominant masculinity in any particular context is not simply the one that forces itself on people but the one that is so socially ingrained that it is almost impossible to imagine anything else. Hegemonic masculinity must also compete with other identities such as femininity, class and age. Consequently, masculinities are not always dominant and are instead subordinate to another identity. As hegemonic masculinity is defined in particular contexts, it can never be fixed and must instead be continually reworked as people move through their lives. Sex differences in the symptoms of depression may be evidence of underlying and common gendered practices.

Enacting depression could be part of enacting gender. Indeed, being depressed would seem to be unmasculine. In an interview-based study involving men who had been diagnosed with depression but were well enough to participate in the research, Reference Emslie, Ridge and ZieblandEmslie et al (2005) found that the recovery process was talked about as successfully renegotiating a masculinity. Thus, actually being depressed would constitute a failure to be masculine. Nevertheless, for a few of the men Emslie et al interviewed, the isolation and loneliness of depression were incorporated as signs of their difference (as more sensitive and intelligent) from others, which seems to suggest that actually being depressed would reaffirm their own masculinity.

As so few men are diagnosed with depression it is important also to look at depression-related practices in non-clinical samples. A focus group study that sought a diverse sample of men from both clinical and non-clinical populations looked at how they talked about seeking help for physical and mental health problems (Reference O'Brien, Hunt and HartO'Brien et al, 2005). The authors found considerable resistance to talking about mental ill health, particularly among young men, for whom masculinity appeared to require being strong and silent about emotions.

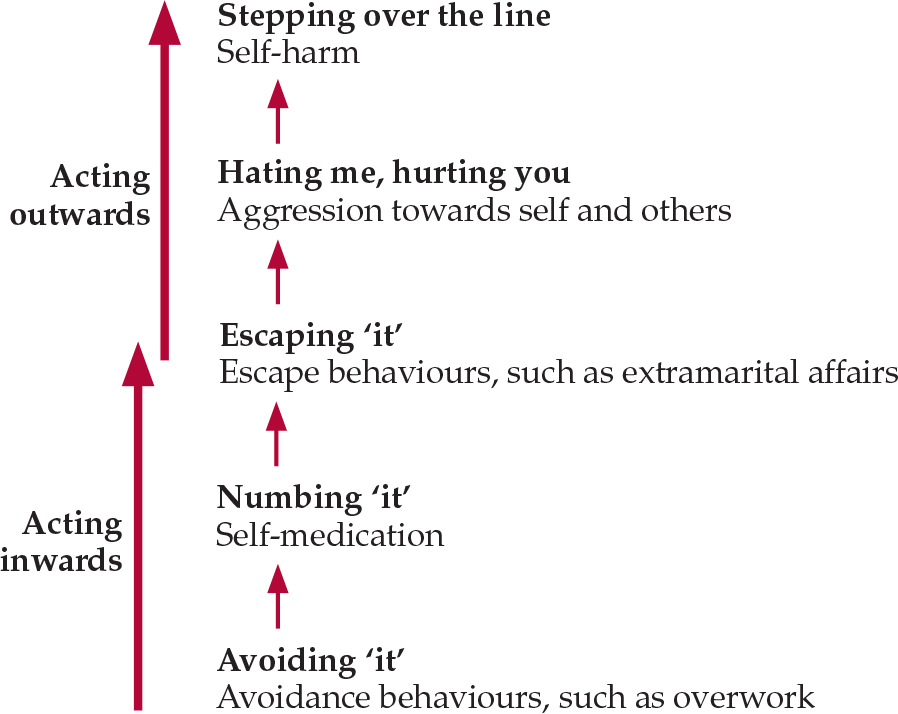

Masculinity can be practised by both men and women, which means that women need to be included when considering depression in men. Reference Brownhill, Wilhelm and BarclayBrownhill et al (2005) conducted focus groups with a non-clinical sample of men and women and found that the important difference was not how depression was experienced but how it was expressed. Their study seems to suggest that depression is part of an inner emotional world that is contained, constrained or set free by gendered practices. The ‘big build’ (Fig. 1) is the descriptive model Brownhill et al developed to explain how masculine practices in relation to depression result in a debilitating trajectory of destructive behaviour and emotional distress. These practices start as avoidance, numbing and escaping behaviours that may escalate to violence and suicide. The point seems to be that there is no difference in the depression men and women experience but that there are important differences in how depression is ‘done’ or enacted in terms of masculinities or femininities.

Fig. 1 The ‘big build’: the upward trajectory of the masculine enactment of emotional distress (after Reference Brownhill, Wilhelm and BarclayBrownhill et al, 2005).

From the research on depression and hegemonic masculinities, it might be suggested that the destructive behaviours such as violence in intimate relationships, substance misuse and suicide are ways of ‘doing’ depression that enact particular masculinities. Further, current mental health practices in the diagnosis and treatment of depression might be seen as enacting femininities. From the concept of hegemonic masculinity, depression in men is not masked but is often visible in abusive, aggressive and violent practices; nor are these behaviours a sign of a male form of depression: women can ‘do’ masculinity and may cope with their depression in similar ways. The point for service provision is that depression may underlie wider issues of mental health (such as substance misuse) and criminal behaviour.

Although hegemonic masculinity may offer clinicians a more nuanced view of their clinical practices and how their clients act out their difficulties, it fails to offer any specific treatment possibilities.

To date, the research on hegemonic masculinity and depression has utilised focus group and interview methods. As masculinity is understood in terms of constantly recurring practices, research needs to adopt methods that identify and study depression-related practices as they occur in real life. Studies have already looked at how masculinities are achieved through destructive behaviours such as crime (Reference MesserschmidtMesserschmidt, 1993) and hooliganism (Reference Newburn and StankoNewburn & Stanko, 1994), and it would be interesting to explore them for depression.

The socialisation of developing boys

In our introduction we presented three reasons for considering men and depression: men are a numerical minority among patients with depression, and they require effective interventions; in community samples there seem to be more men with depression than are receiving treatment for it; and emotional distress in men might indicate depression. Theories of sex differences, gender roles and hegemonic masculinity can be combined in an effort to explain why men are the numerical minority patient group when so many seem to have depression. Although Reference KraemerKraemer (2000) argues that men may be biologically disadvantaged by a fragile X-chromosome, he claims that this disadvantage is immediately mitigated once an infant's sex is known. Boys are subject to their own biological and psychological development that cannot be separated from the cultural and historical context in which they are socialised. The advantage of taking a combined approach is that it should force us to consider the individual and social together.

In a pioneering study of schoolboys, Reference Frosh, Phoenix and PattmanFrosh et al (2002) found that masculinity seemed to be lived through attempts to avoid being seen as feminine or homosexual. In particular, femininity and homosexuality seemed to be associated with displays of emotions and the schools reported that if boys displayed such emotions they were subject to, and would subject others to, insidious bullying. Although usually associated with younger children, the cliché ‘big boys don't cry’ is an example of how a young boy may be denied a masculine identity because he has displayed emotion. It is important to consider what this means for men and depression in practice, as the suggestion seems to be that developing boys are socialised into emotionally inarticulate young men, unable to express depression. If adolescent girls hold the monopoly on discussions relating to emotions, then by implication boys are restricted from entering these domains. This rather stark bipolarisation of emotional-feminine and unemotional-masculine must influence men's ability to recognise their own emotional difficulties, how they express them and how they seek help to cope with them. A further suggestion is that ‘health’ more generally is seen as a feminine issue, which means that the problems of genders roles and masculinities are not limited to emotional health (Reference WhiteWhite, 2006).

Future: gender equality policy

The ‘Real men. Real depression’ campaign of the US National Institute for Mental Health (Reference Rochlen, Whilde and HoyerRochlen et al, 2005) and the publication of the leaflet Men Behaving Sadly by the UK Royal College of Psychiatrists (2006) demonstrate the growing recognition of depression in men. However, recent changes towards proactive gender equality may mean that health services have to adapt and incorporate an explicit focus on men and depression. The UK Equality Act 2006, which came into force April 2007, places a statutory duty (termed the ‘gender duty’) on public bodies to ensure that where men and women have different needs services are planned and developed in ways that successfully meet them. If, for example, a local coroner's office were to report a rate of suicide greater in men than in women, we would presume that under the gender duty the local health services would need to do something to reduce male suicide. Nevertheless, health services currently lack the expertise required for providing solutions targeted specifically at men (Men's Health Forum, 2006), which means that they may fail to meet their obligations under the gender duty. Health service projects have been designed to meet men's health needs and it is important that we learn from these as services are developed on the basis of the different needs of men and women.

Declaration of interest

A. W. is Chair of the Men's Health Forum in England and Wales.

MCQs and EMI

-

1 A man attends your surgery and you consider him to be typical of the masculine gender role. The most productive tactic to explore the possibility that he has depression is to:

-

a ask how he feels about his emotional difficulties

-

b focus on his physical symptoms

-

c ask about any issues or problems he is experiencing.

-

-

2 Assuming that ‘male depression’ exists, diagnosis should be based on:

-

a international diagnostic criteria with both men and women

-

b international diagnostic criteria with women and ‘male depression’ instruments with men

-

c diagnostic criteria and ‘male depression’ instruments with both men and women.

-

-

3 Hegemonic masculinity is best described as:

-

a the taken-for-granted view of what it is to be a man in a specific context

-

b the norm that men aspire to

-

c the societal view of what it is to be a man that is forced on everyone.

-

EMI

Theme: clinical diagnosis

Options

-

a weight loss

-

b disturbed sleep

-

c ideas or acts of self-harm or suicide

-

d alcohol dependence during difficult times

-

e loss of interest or enjoyment f physical aggression.

For each patient in the scenarios below, select from the above list the symptom that is absent from international classifications of depression:

-

i A 40-year-old man is cheerful and friendly when he attends your surgery. When pressed, he reports that for as long as he can remember he has had periods when he loses interest in his hobbies, eats too much and puts on weight. When asked about his strategies for dealing with these periods he reports that the only thing that helps him is drinking, otherwise things get out of control as he cannot relax.

-

ii A 22-year-old man attends your surgery with visible bruising to his face and knuckles. Since graduating from university, he has separated from his long-term partner and had to relocate away from friends and family to start his job. After further discussion, he reports that has been feeling low and has moments when he becomes inexplicably angry, starting fights for no reason.

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | F | a | T |

| b | F | b | F | b | F |

| c | T | c | T | c | F |

EMI correct matchings

| I | ii |

|---|---|

| d | f |

Acknowledgement

We thank David Conrad for comments on this article.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.