Revalidation is the process by which licensed doctors in the UK demonstrate to the General Medical Council (GMC) that they are up to date and fit to practise and that they are complying with all the relevant professional standards (Box 1). It also provides assurance of this to patients, the public, employers and other healthcare professionals. Revalidation aims to improve the quality and safety of patient care, strengthen professional development and identify doctors who need support early (Reference FisherFisher 2014).

BOX 1 Who needs to be revalidated?

Any doctor who wants to retain a licence to practise in the UK needs to be revalidated. This includes trainees, tribunal and second opinion appointed doctors.

Doctors who do not undertake clinical work do not need a licence to practise and can give up their licence while maintaining a registration with the GMC.

Background to revalidation

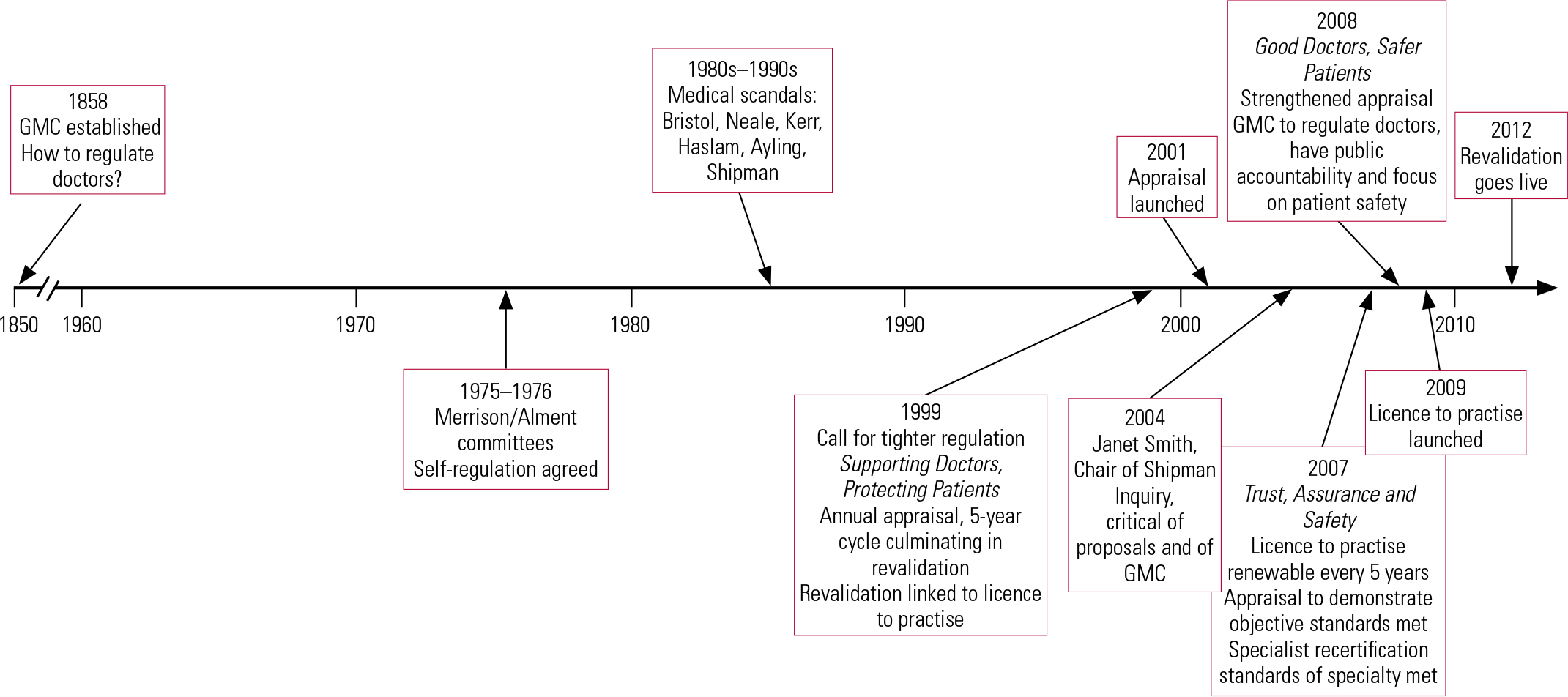

The regulation of doctors has been the subject of debate for years but self-regulation was the agreed standard (Fig. 1). A number of medical scandals in the 1980s and 1990s, including the public inquiries into paediatric surgical deaths at Bristol Royal Infirmary and the deaths of a large number of patients under the care of Dr Harold Shipman, were followed by demands for tighter medical regulation. Liam Donaldson, then Chief Medical Officer, advocated appraisal as a method of supporting doctors and identifying problems (Reference DonaldsonDonaldson 1999). The GMC then proposed a 5-year cycle of annual appraisal culminating in revalidation linked to a licence to practise. Appraisal was introduced in 2001, but revalidation was the subject of further consultation.

FIG 1 Timeline for the regulation of doctors: 1850–2012. GMC, General Medical Council.

In 2004 Dame (now Lady Justice) Janet Smith, in her role as Chair of the Shipman Inquiry, cast serious doubts on the effectiveness of the GMC’s proposals (Reference SmithSmith 2004). She did not trust the annual appraisal of National Health Service (NHS) doctors to provide a true evaluation of the range of a doctor’s performance and did not feel that this system would detect doctors who were incompetent or providing a poor standard of care. Liam Donaldson responded to these concerns with proposals for strengthened appraisal and a requirement for the GMC to regulate the practice of doctors, have increased public accountability and focus on patient safety (Department of Health 2008).

The Department of Health (2007) had already highlighted the need for standardisation of the process and stated that all doctors would need a licence to practise which would be renewed every 5 years; appraisal was to demonstrate that objective standards had been met, and specialist recertification required demonstration that standards that applied to a particular medical specialty were met. Relicensing and recertification were subsequently combined into one process: revalidation.

Licence to practise was launched in November 2009 and revalidation went live in December 2012.

The mechanics of revalidation

The Royal College of Psychiatrists’ guidance on revalidation gives detailed information about the process and standards and I recommend it to readers (Box 2; Royal College of Psychiatrists 2012).

BOX 2 Royal College of Psychiatrists’ recommendations for revalidation

Within a 5-year cycle the doctor should:

-

• undertake 250 hours of CPD

-

• engage in 10 case-based discussions

-

• demonstrate use of appropriate outcome measures

-

• obtain feedback from at least one patient and one colleague using a GMC-approved tool

-

• undertake two clinical audits and one records audit

-

• review and reflect on significant events and complaints

Revalidation started on 3 December 2012 and all licensed doctors will have received a revalidation date between April 2013 and March 2016. Most organisations expect doctors to have an appraisal by a responsible officer (see below) annually from 1 April 2012 and this is often a condition of employment. In the first cycle of revalidation, doctors will have fewer than five such appraisals, depending on their revalidation date, but will have to demonstrate all six types of supporting information (see below). In future revalidation cycles this information (evidence) can be spread over the 5-year period. If no problems are raised at the appraisal, the responsible officer will recommend revalidation to the GMC on the doctor’s behalf (the doctor does not have to do anything).

Fitness to practise v. fitness for purpose

Through revalidation, the GMC ensures that doctors are fit to hold a licence to practise, i.e. are fit to practise. The GMC’s Good Medical Practice Framework for Appraisal and Revalidation (General Medical Council 2013a) is based on its core guidance for doctors Good Medical Practice (General Medical Council 2013b). It does not prescribe the number of activities or amount of evidence required, as this will vary by specialty and circumstance. The Academy of Medical Royal Colleges has produced core guidance in this area (Academy of Medical Royal Colleges 2012) and each medical Royal College has more specific guidance (for psychiatry, see Royal College of Psychiatrists 2012). Trusts may adopt the guidance of the relevant College and it is this standard that has to be met in order for the doctor to be fit for purpose to work in that particular organisation. There can be a situation therefore that the GMC grants a licence to practise but an organisation does not feel that the doctor has reached the required standard to be fit for purpose.

The designated body

For the purpose of revalidation the first thing the doctor should do is identify their designated body (DB). Almost every doctor has a connection with a single designated body, which is the organisation that provides regular appraisal and helps with revalidation. Boxes 3 and 4 clarify the situation for doctors who do not have an employer-related designated body. Only UK organisations can be designated bodies, as the legal rules only cover the UK. For most licensed doctors on the medical register, their designated body will be displayed in their GMC Online account. If it is not, there is a set of rules to follow to establish who is the designated body (it is usually the organisation where the doctor spends most of their time). The GMC has a list of all designated bodies and an online flow chart to help identify the appropriate designated body. The rules and list are currently available at www.gmc-uk.org/doctors/revalidation/12387.asp.

BOX 3 Tribunal and second opinion appointed doctors

Tribunal or second opinion appointed doctors who are not employed by an NHS trust or are retired from the NHS have to find a designated body and responsible officer for the purposes of appraisal and revalidation. In some cases the Royal College of Psychiatrists will provide this function and the GMC will advise depending on the particular circumstances.

BOX 4 A ‘suitable person’

There are some doctors who do not have a designated body and for those it is possible for the GMC to approve a ‘suitable person’ to act as responsible officer. This will be someone who is already a responsible officer or holds a post with similar responsibilities. A suitable person has to demonstrate that they meet the criteria for the role, and has the same responsibilities to the doctor as a responsible officer.

Examples of doctors who might require a suitable person include those who work solely in private practice but not within a private hospital, or academics who do not have an honorary clinical contract.

The responsible officer

Each designated body has a responsible officer (RO), who makes recommendations to the GMC about revalidation of the doctors connected to it. The responsible officer is employed by the designated body and has duties set out in statute (Department of Health 2010). All practising doctors on the medical register in England now relate formally to a responsible officer, who will usually be the organisation’s medical director or a doctor designated by the organisation for which they work or provide services. The responsible officer has to have been a licensed medical practitioner for 5 years and is accountable to the board of the designated body. The responsible officer has responsibilities covering the clinical governance of the doctors for whom they are responsible and making revalidation recommendations.

The responsible officer role covers:

-

• contracts of employment or contracts for the provision of services

-

• communication with the GMC about all matters concerning fitness to practise

-

• monitoring conduct and performance

-

• appraisal

-

• responding to concerns from any quarter regarding the organisation’s doctors.

The responsible officer makes the recommendations about a doctor, but it is the GMC that issues (or does not issue) the revalidation. The responsible officer can do one of the following three things when asked to make a recommendation about a doctor.

-

• Make a positive recommendation: this means that the doctor has participated in the process and has provided all the supporting information required and there are no concerns.

-

• Make a deferral request: this can be done when there is not enough information on which to make a decision, but no evidence that the doctor has not engaged in the process. This could be because of maternity leave, sick leave, a break from practice or a local disciplinary process involving the doctor, the outcome of which the responsible officer needs to consider before making a recommendation. A deferral request is not a route to raise concerns about a doctor. (If a doctor is subject to an ongoing GMC fitness to practise investigation the GMC will automatically defer the revalidation date.)

-

• Make a notification of non-engagement: this happens when a doctor has not participated in the processes for appraisal and revalidation. The responsible officer judges whether or not there are reasonable circumstances that explain this. On receipt of this notification, the GMC will remind the doctor that it is a requirement to engage within 28 days in order to maintain a licence and if the doctor does not engage within this time their licence will be removed.

The Follett principles

Following the public inquiry into the unauthorised removal, storage and disposal of human tissue at Alder Hey Children’s Hospital (Reference RedfernRedfern 2001), the Secretary of State asked Professor Sir Brian Follett and Michael Paulson-Ellis to review the appraisal, disciplinary and reporting arrangements for joint appointments between the NHS and universities. The report, published in 2001, is the basis of the Follett principles (Box 5) (Reference Follett and Paulson-EllisFollett 2001). All medically qualified staff working jointly for both the NHS and a higher education institution should be employed according to these principles. The key message is that NHS and university organisations must work together to integrate the separate responsibilities.

BOX 5 The Follett review principles for joint NHS/university appointments

-

• There should be joint bodies responsible for planning services and managing staff

-

• Staff duties should be clearly articulated and staff should know to whom they are accountable

-

• Honorary and substantive contracts should be cross-referenced, consistent and issued as a joint package; they should be interdependent, and each body has the responsibility to inform the other about any issues relating to appraisal, job planning, discipline and dismissal

-

• Appraisal and performance review for clinical duties should be based on the system for NHS consultants

-

• It is recognised that honorary and substantive contracts are distinct, but they must be managed as a whole

-

• Appraisals are to be undertaken jointly, but permission must be sought from the doctor for the exchange of sensitive material between the two employers

-

• Honorary contracts should contain an interdependency clause, so that if the substantive contract is terminated for any reason the honorary contract can also be reviewed

-

• The university and NHS organisation should work together to establish procedures for dealing with identified concerns

Doctors working less than full time

Doctors working less than full time still require appraisal. They need the same time to prepare for appraisal, but it may take longer to collect supporting information as they have fewer activities on which to draw. This should be taken into account in job planning.

Trainees

Trainees on deanery-managed training programmes, including locums appointed for training (LATs), will be revalidated by a recommendation from their responsible officer. The responsible officer and designated body will depend on where in the UK the trainee is working (Box 6). The GMC provides useful information for trainees regarding establishing who their responsible officer is and when their revalidation date will be (General Medical Council 2013c). The responsible officer is asked to confirm that there are no un-addressed concerns about a trainee’s fitness to practise and will make a recommendation based on a ‘strengthened annual review of competence progression’ (ARCP) or equivalent, for example a record of in-training assessment (RITA). A strengthened ARCP is one supplemented by information regarding concerns about capability or conduct or involvement in significant events (also referred to as critical or serious untoward incidents) or complaints. This information will be provided by the host trust to the responsible officer. The outcomes of the ARCP (or equivalent) and revalidation are linked in this process, but are separate decisions. For other trainees, such as trust locums, the process will follow that of the consultants and specialty doctors of the employing organisation.

BOX 6 Who’s who for trainees?

-

• In England, the designated body is the local education and training board (LETB) and the responsible officer is the postgraduate dean

-

• In Scotland, the designated body is NHS Education for Scotland and the responsible officer is the medical director of NHS Education for Scotland

-

• In Wales, the designated body is the Wales Deanery and responsible officer is the postgraduate dean

-

• In Northern Ireland, the designated body is the Northern Ireland Medical and Dental Training Agency (NIMDTA) and the responsible officer is the postgraduate dean

Good Medical Practice

Good Medical Practice provides the standards on which to judge a doctor’s performance. The document, which was last updated in 2013 (General Medical Council 2013b), describes four domains that cover the spectrum of medical practice (Box 7). Each domain is described by three attributes which define the scope and purpose of the domain. The guidance gives examples of each attribute. A doctor is not expected to show evidence of competency in all the attributes at each appraisal: it will accumulate over the 5-year appraisal period. It is not necessary to map the evidence onto the attributes, although some doctors prefer to do this. Good Medical Practice is a guide for the collection of supporting information which can then be put into context for the individual doctor at appraisal.

BOX 7 The domains and attributes of Good Medical Practice

Knowledge, skills and performance

-

• Maintain professional performance

-

• Apply knowledge and experience to your practice

-

• Ensure documentation is clear, accurate and legible

Safety and quality

-

• Contribute to and comply with systems to protect patients

-

• Respond to risks to safety

-

• Protect patients and colleagues from risk posed by your health

Communication, partnership and teamwork

-

• Communicate effectively

-

• Work constructively with colleagues

-

• Establish and maintain partnerships with patients

Maintaining trust

-

• Show respect for patients

-

• Treat patients and colleagues fairly and without discrimination

-

• Act honestly and with integrity

Supporting information

The GMC has published guidance (General Medical Council 2012a) on the supporting information/evidence required to demonstrate competence across the domains of Good Medical Practice. The guidance falls under four broad headings:

-

• general information

-

• keeping up to date

-

• review of practice

-

• feedback on practice.

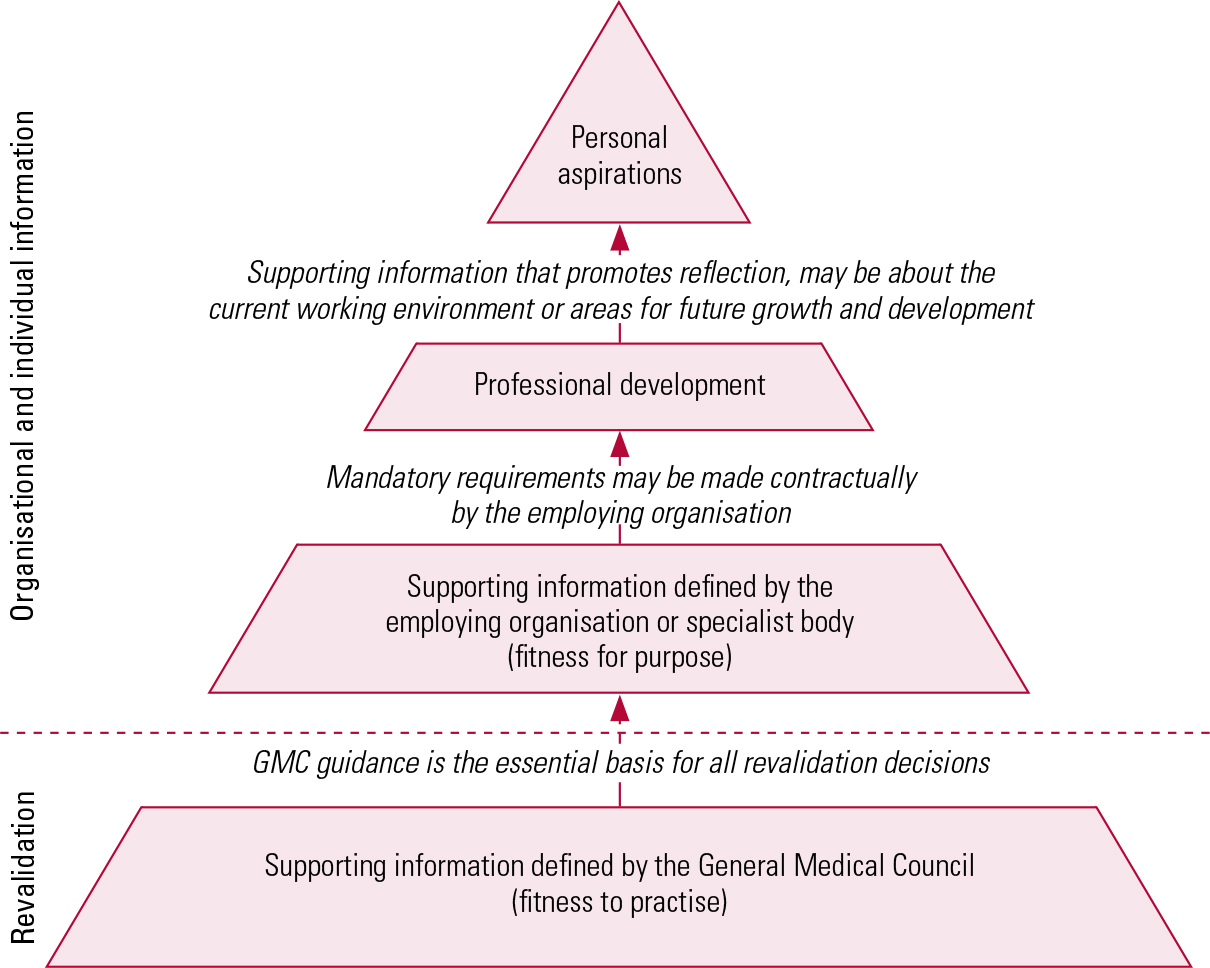

There are six types of supporting information that you must provide at least once during each 5-year revalidation cycle (Box 8). It is envisaged that discussion and reflection on these will allow you to demonstrate your practice against the 12 attributes outlined in Good Medical Practice. Figure 2 shows the levels of supporting information required for different purposes.

BOX 8 The six types of supporting information for revalidation

-

• CPD

-

• Quality improvement activity

-

• Significant events

-

• Feedback from colleagues

-

• Feedback from patients

-

• Review of complaints and compliments

FIG 2 Levels of supporting information. Information required by the General Medical Council should form the foundation, even though for most doctors it will be the smallest proportion of the information submitted (Revalidation Support Team 2013a, with permission).

General information

General information provides the context about you and your work. This includes personal details, the scope of the work, record of previous appraisals, and progress against the previous year’s personal development plan (PDP). You are required to sign statements of probity and health to show that you accept the professional obligations placed on you in Good Medical Practice in these areas and declare any relevant issues.

When providing supporting information consider what it shows and how it demonstrates your practice. Box 9 relates supporting information to Reference MillerMiller’s (1990) hierarchy used in the assessment of clinical competence.

BOX 9 Supporting information: some further thoughts

George Miller proposed a framework for the assessment of clinical competence in 1990 (Reference MillerMiller 1990). This ‘pyramid of clinical competence’ can be useful when assessing or providing evidence for appraisal.

The lowest level of the pyramid is that the doctor ‘knows’ (knowledge), with increasing levels of competence to ‘knows how’ (competence), ‘shows how’ (performance) and ‘does’ (action). ‘Does’ is the way a doctor acts in reality rather than in test conditions.

Much of the evidence that we provide demonstrates the lower levels of the pyramid and sometimes not even that, e.g. attendance at a CPD event does not tell us much except that the doctor was there – which is why reflection on and application of CPD are so important.

Keeping up to date

CPD

Continuing professional development (CPD) covers a broad range of activities. Good Medical Practice requires doctors to keep their knowledge and skills up to date and to ‘take part in educational activities that maintain and further develop competence and performance’. CPD should be planned to cover the whole scope of your practice and take into account your needs and those of the service in which you work or the roles that you have. CPD plans should be discussed and approved within your peer group to give an external objective view.

The most important part of CPD is reflection on what you have learned and its relevance to your practice. Is it helpful to reinforce the learning using a reflective template, or through discussion with your peer group or at appraisal (Box 10). You should think outside the box for CPD activities by considering how learning will be best achieved. Is a conference the best way of getting the information? Would an experiential activity be more suitable? You should consider your individual learning style. And you should consider the acquisition of skills (such as negotiation, time-keeping, self-awareness) that you may not associate with medical practice that could help you perform better and activities to enhance your own health and well-being.

BOX 10 Enhancing the value of CPD

Reference Mathers, Mitchell and HunnMathers et al (2012) studied the effect of CPD on doctors’ performance and patient outcomes. They found little evidence that it improved professional effectiveness or had a direct effect on patient care. The importance of reflection on CPD was widely recognised among the doctors in the study, but not always acted on in a structured way. Among the study’s recommendations to enhance the value of CPD were:

-

• reflection on learning and how it relates to improved patient care or service provision

-

• patient and public involvement in CPD

-

• recognition of the importance of informal learning and learning across professional disciplines

-

• paying attention to the doctor’s own health and well-being in CPD

-

• quality assurance of the CPD provided

-

• employers’ responsibility to provide resources for CPD

Review of your practice

Quality improvement activities

Quality improvement activities can be demonstrated in all roles – clinical, teaching, research and management – and include a broad range of possibilities. For the purposes of revalidation you have to demonstrate that you regularly participate in activities that review and evaluate the quality of your work. This is often shown by audit. The key is to show an improvement in an area that you were personally involved in or what your part in it was. One of the principles of revalidation is that the effort must be proportionate, so whenever possible data used for audit should be readily available or collected routinely. As elsewhere, reflection on the results is the most important part of undertaking an audit. What did it show? How has this improved quality? If it has not, why not? Should a new standard be implemented? How will this be sustained? Is re-audit necessary to demonstrate change? Is the audit cycle completed?

Case-based discussion (CbD) constitutes a quality improvement activity and it can be also used to reflect on a complaint or significant event. It provides the opportunity for you to discuss a case with a colleague and for your colleague to assess a specific area of your clinical practice or record-keeping against agreed standards. Reference Mynors-Wallis, Cope and BrittlebankMynors-Wallis et al (2011) set out suitable standards, together with a scoring guide. They suggest that 10 CbDs be undertaken in each 5-year cycle and that some of the cases be chosen at random to remove bias. Discussions can take place one-to-one or in a peer group, provided that one member of the group takes responsibility for giving feedback. The focus of the discussion should be decided in advance and the assessor should have the opportunity to review the case notes before the discussion. The assessor should score the discussion against the agreed standards using a scoring guide and provide constructive feedback as part of a developmental exercise.

Other types of peer review, such as direct observation of practice, can also give valuable information. Again it should be carried out against an agreed standard. Observation of practice can be time-consuming, but it provides more objective evidence as self-report is always open to bias, whether conscious or unconscious.

Reference NorciniNorcini (2003) stated that a doctor’s performance could be assessed by patient outcomes, the process of care (i.e. the care the patient actually receives and how it is delivered) and the numbers seen. All of these measures are useful, but none is foolproof when considering an individual doctor’s performance. Can the outcome be shown to be solely attributable to the doctor’s intervention? Were there confounding variables? Was the sample large enough to make the judgement reliable? Process of care gives a more direct indication of what the doctor actually did, but sometimes the skill is to know when to deviate from the process. Similarly, evidence of numbers seen gives an indication of activity, but not of quality of intervention. A mixture of types of evidence will give the best indication of performance.

Significant events

Revalidation places great importance on the monitoring of and reflection on significant events. A significant event is defined as ‘any unintended or unexpected event, which could or did lead to harm of one or more patients’ (General Medical Council 2012a: p. 9). This includes incidents that did not cause harm but could have done or events that should have been prevented. Employers collect such information routinely and if you are self-employed you must keep a record of such events. The task for appraisal is to ensure that you know about and have reflected on any events in which you were involved. Lessons learned and change of practice need to be discussed with the appraiser and recorded. It is important to maintain an openness and willingness to be challenged in such discussion to obtain the maximum benefit for your practice and the service.

Doctors are required to discuss any issues regarding performance or disciplinary procedures at their appraisal meetings.

Feedback on your practice

Feedback from colleagues and patients

Multisource or 360-degree feedback involves collecting information from a group of individuals about your practice and performance. It is recommended that you use standard questionnaires that comply with GMC guidance. There are various products available for this purpose and there is nothing to stop you designing your own as long as it meets the GMC requirements and the administration of the results is done independently. Feedback can be collected prospectively or retrospectively, by post, telephone or face to face. Reference Richards, Campbell and DickensRichards et al (2011) have shown that the method of administration of feedback questionnaires can influence the results. It is important therefore to ensure it is done consistently. The GMC (2012a) suggests that you collect multisource feedback once within every revalidation cycle. If you do not see patients as part of your role you do not have to produce patient feedback, but consider who could give feedback on your performance instead.

The number of people you select to provide feedback may depend on the setting in which you work and how many people are able to give feedback. The GMC has not specified the number of people that should be canvassed. If you are using a validated questionnaire, find out how many it has been validated for and collect at least that number of responses. If using the GMC questionnaire the numbers suggested are 15 colleagues and 34 patients to give the best picture of the doctor’s practice (General Medical Council 2012b).

You should canvass a wide selection of colleagues with whom you work, including trainees, consultants and non-clinical staff such as administrators. Most questionnaires explain that the person completing the form only has to answer those questions about the doctor’s practice with which they are familiar.

It is important to invite a random selection of patients, to avoid bias. For some patient groups, feedback can be more difficult to obtain and thought needs to go into how best to obtain it. In intellectual disability (learning disability) and perhaps children’s and young people’s services picture-based feedback may be more relevant than traditional questionnaires. Carers can also be involved in giving feedback, especially in dementia or learning disability services.

In areas such as psychotherapy or forensic psychiatry, asking patients for direct feedback about their doctor could potentially compromise the therapeutic relationship and clinical care, so careful thought and design needs to be put into the process.

You will be asked during your appraisal how and why you selected the people who have provided feedback.

The feedback that you receive should be seen as information to inform your practice rather than personal validation, attack or criticism. Reflection on the meaning of the results, the relevance to your practice and the opportunity to develop is as important as the results themselves. Self-rating allows comparison of your views with those of others and any mismatches are worthy of consideration.

Complaints and compliments

You must also reflect on complaints and compliments. Employers are likely to collect complaints and if you are self-employed you must do so yourself. A complaint is defined as ‘a formal expression of dissatisfaction or grievance […] about an individual doctor, the team or […] the care of patients where a doctor could be expected to have had influence or responsibility’ (General Medical Council 2012a: p. 12). Compliments are usually not treated formally in the way that complaints are and they may be directed to you rather than to the organisation. Complaints and compliments provide feedback on your performance and during appraisal you should demonstrate an awareness of them, any investigation and actions that resulted and any opportunities for professional development or change to practice.

Useful templates for structured reflection on audit, feedback, complaints and significant events are contained in the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ guidance on revalidation (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2012).

Teaching, research and management roles

All of a doctor’s roles are considered during appraisal, including teaching, research and management, and the six types of supporting information (Box 8) within the 5-year cycle need to be produced. The GMC has published useful documents containing standards against which you can measure your performance (General Medical Council 2006, 2010, 2013b).

Whole scope of practice

Appraisal now takes into account the whole scope of a doctor’s practice, not just that within the designated body. This includes private practice, medico-legal work and any other NHS or non-NHS roles, even if these are infrequent. Exactly the same types of supporting information are required for each revalidation cycle (Box 8), and complaints, significant events or concerns relating to the doctor’s work must be produced for discussion at appraisal. The amount of information provided should be commensurate with the amount of activity. The British Medical Association’s expert witness guidance might be a useful resource for assessing your medico-legal work (British Medical Association 2008).

Personal development plans

Discussion at appraisal leads to the production of a personal development plan for the year ahead. This should be driven by you and reflect your own approach to learning. It needs to have SMART objectives: specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and timely. Part of the appraisal discussion will include progress on last year’s plan: what was achieved and how this affected practice, what was not achieved and why not.

Quality assurance

Appraisal is designed to be more challenging and robust than before. The appraiser has to judge the individual’s engagement in the process, analyse and synthesise the information produced and set it in context. The whole scope of a doctor’s practice is reviewed and a decision made as to progress towards revalidation. The responsible officer has to ensure that the process is consistent and fair. Quality assurance of appraisers and the appraisal process can be provided by ensuring that (Revalidation Support Team 2014):

-

• appraisers meet the personal specification given in the job description and are interviewed before appointment

-

• appraisers receive specific training

-

• appraisal outputs are rated for quality by an independent panel and any problems are rectified through retraining or withdrawal of the appraiser

-

• appraisers attend regular support meetings with an opportunity for peer review and knowledge update

-

• feedback from doctors on their appraiser and the appraisal process is collated and sent back to appraisers to reflect on for their own appraisal.

The Revalidation Support Team (Box 11) has produced a competency framework for appraisers which includes areas such as professional responsibility, knowledge and understanding, professional judgement, communication skills and organisational skills (Revalidation Support Team 2014). It is a useful guide when training or providing refresher sessions for appraisers.

BOX 11 The Revalidation Support Team

The Revalidation Support Team (RST) was the body responsible for the implementation of revalidation in England on behalf of the Department of Health. The RST closed on 31 March 2014 and relevant information regarding revalidation is now available on the NHS England website (www.england.nhs.uk).

Job planning and revalidation

The new process is rigorous and requires collection and collation of specific evidence, so doctors will require protected time in their job plans to prepare for appraisal. It is likely that 1 to 1.5 programmed activities (PAs) are required to undertake all the activities, including CPD and audit. Likewise, appraisers require time to be trained and keep up to date and we (Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust) suggest that for 10 appraisals per year an appraiser would require 1 PA in their job plan. We recommend that our appraisers undertake 8–10 appraisals per year, so that they have regular exposure to appraisal and high standards are maintained. Indemnity for appraisers will depend on whether these are performed on behalf of an employer or independently (Box 12).

BOX 12 Indemnity cover for appraisals

Conducting appraisals is part of an employee’s professional duty and therefore the employing body is liable for it. In NHS organisations, indemnity cover for appraisals is usually provided by the NHS Litigation Authority. However, if an appraisal is undertaken by an independent contractor, the independent contractor is liable for this work and has to make his or her own arrangements for indemnity cover.

The aims of appraisal and revalidation fit with some of the recommendations from the Francis report (Reference FrancisFrancis 2013) – see Box 13.

BOX 13 How does revalidation fit with the Francis report?

The Francis report from the public inquiry into the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust identified serious concerns about the standards of care and culture of the organisation (Reference FrancisFrancis 2013). There are 290 wide-reaching recommendations in the report, but some fit neatly with the principles behind revalidation and serve to reinforce the importance of the robust appraisal proposed. The Francis recommendations include:

-

• always putting patients first

-

• ensuring that medical training and education are adequate

-

• having a robust complaints management system

-

• evaluation of practice through audit.

The report suggests that doctors must adopt a critical eye and willingness to challenge, as well as a culture of openness and an ability to see the bigger picture.

Remediation

One of the principles of revalidation is early identification and prevention of problems. Remediation is the process of addressing performance concerns that have been recognised through assessment, investigation, review or appraisal so that the practitioner has the opportunity to return to safe practice. It covers a broad range of interventions, including simple advice, referral to an occupational health service, formal mentoring, further training, re-skilling and rehabilitation (Department of Health 2011). Decisions about what constitutes a concern requiring remediation and what is proposed as CPD will be made by the appraiser.

Lessons learned in the first year

Having survived the rather strangely named ‘year zero’ (April 2012 to March 2013) and overseen 35 recommendations for revalidation I have reflected on the process.

I spent significant time in the first 3 months meeting consultants to give them information about the process. This was time well spent and it gave me the opportunity to listen to their concerns and allay most of these. Some older consultants and those coming up to retirement required more persuading and sometimes it was a case of telling them: ‘We have to do this so let’s get on with it and get the best out of it!’. Most people have since commented that it is much easier then they expected.

The Medical Appraisal Guide (MAG) form (Box 14) is excellent and once we ironed out the IT teething problems with old versions of Adobe reader on our NHS computers it worked well. It is easy to use and systematically covers all the necessary aspects for the new-style appraisal.

BOX 14 The Medical Appraisal Guide (MAG)

The MAG is an electronic portfolio produced by the Revalidation Support Team (2013b) which goes through all the items necessary for a revalidation-ready appraisal. It is available at www.england.nhs.uk/revalidation/appraisers/med-app-guide free of charge. Other products are available that provide similar functions.

It is essential to have sufficient trained appraisers to allow appraisals to be undertaken in a timely fashion. We identified the number of appraisers we needed by establishing how many appraisals each appraiser would be expected to do and costed this in terms of PAs in job plans. Some slack in the system is necessary, but has to be weighed against the cost of having more appraisers than you need and appraisers doing enough appraisals to retain their skills.

We found multisource feedback from children and young people, people with intellectual disabilities and older people problematic and are working on alternatives to the standard questionnaires using pictures and involving carers.

When I started there was no system to inform doctors of their involvement in significant events or complaints. We explained what we needed to IT and clinical governance colleagues and now have a dashboard system which provides information about and complaints against each doctor to inform appraisal. This is updated daily from the clinical risk department. This dashboard is accessible to the doctor and to the doctor’s line managers but no one else. I have seen this done manually in some trusts, which may be appropriate for smaller organisations. It is certainly worth liaising with IT and clinical governance at an early stage.

We had hoped to develop our dashboard system for the management of appraisal, but decided to purchase an off-the-peg system that meets our requirements. We had demonstrations from a number of companies that provide such software, and found that the differences between them are small and mainly relate to the population for which they were developed: general practitioners, hospital doctors, etc. A word of warning: information governance requirements are the biggest sticking point in implementing an external system such as this and if you are using such a system get IT involved from the outset.

In my view, good-quality information, reflection and robust, supportive challenge are the elements essential to appraisal and revalidation.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 Revalidation was introduced to:

-

a provide assurance to patients of doctors’ fitness to practise

-

b improve the safety and quality of patient care

-

c identify doctors who need support

-

d strengthen doctors’ professional development

-

e all of the above.

-

-

2 The following is an essential type of supporting information for revalidation:

-

a patient outcome measures

-

b clinical audit data

-

c case-based discussion

-

d multisource feedback

-

e 250 hours of CPD per 5 years.

-

-

3 The responsible officer:

-

a is responsible for the clinical governance of a doctor’s practice

-

b decides which doctors should be revalidated

-

c must be a medical director

-

d can request a deferral of revalidation on the basis of a doctor’s non-engagement

-

e is an independent contractor.

-

-

4 The following is not a domain of Good Medical Practice:

-

a maintaining trust

-

b knowledge, skills and performance

-

c communication, trust and partnership

-

d communication, partnership and teamwork

-

e safety and quality.

-

-

5 Appraisal:

-

a involves challenge and reflection on the evidence provided

-

b can be delivered by the same appraiser for up to 5 consecutive years

-

c must be undertaken in the first quarter of the year

-

d cannot be performed by the doctor’s line manager

-

e must be completed on the electronic Medical Appraisal Guide form.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | e | 2 | d | 3 | a | 4 | c | 5 | a |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.