The Laboratory of Archaeology at the University of Georgia (UGA; hereafter, “the Laboratory”) started off in 1938 as a place to teach archaeological methods. However, since its formal establishment in 1947, it has evolved into a large curation repository with over 20,000 cubic feet (566 m3) of cultural material. For the majority of its history, the Laboratory focused more on teaching and research. Only within the last 25 years has the focus shifted to collections and curation practices. Similar to other curation repositories, we are now dealing with curation issues that the Laboratory overlooked in the past.

Perhaps one of the greatest issues facing the Laboratory and other institutions in the United States that house cultural material is the continued partial or complete lack of adherence to the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). The passage of NAGPRA in 1990 required all institutions that received federal funding to compile inventories and summaries, consult with Tribes, and then repatriate Ancestors, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony (hereafter, “NAGPRA cultural materials”). Although many institutions—including the Laboratory—did compile and submit information, there were only sporadic attempts at consultation with federally recognized, descendant Tribal communities to repatriate, and many institutions considered their compliance obligations with respect to NAGPRA to be complete (Table 1).

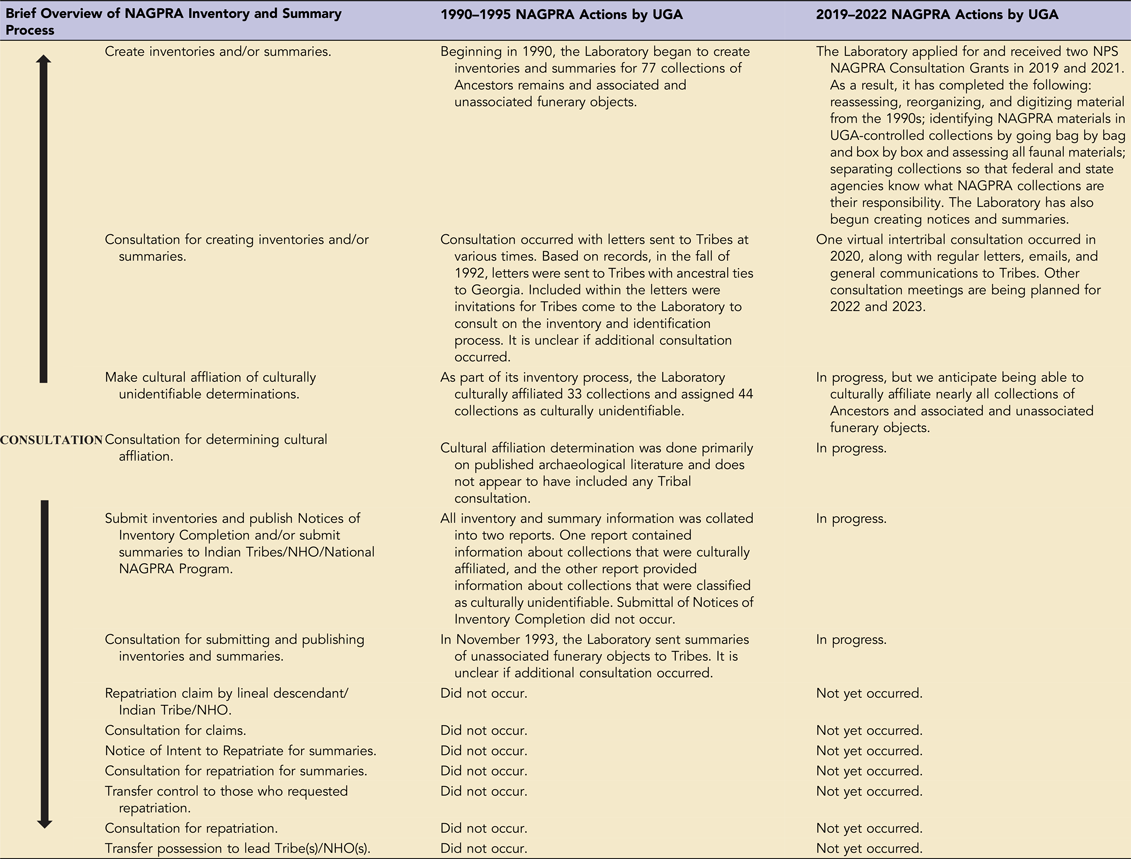

TABLE 1. Comparison of NAGPRA Actions by the University of Georgia Laboratory of Archaeology.

Note: For more detailed information on steps for NAGPRA, please see https://www.nps.gov/subjects/nagpra/getting-started.htm.

In 2019, the Laboratory's staff recognized these missteps, which led to a reevaluation of the Laboratory's approach to NAGPRA implementation and a renewed engagement with federally recognized, descendant Tribal communities. Although our initial conversations with communities centered on NAGPRA compliance, these discussions quickly expanded and became the catalyst regarding changes in research integrity within the Laboratory's overarching philosophy—not just with NAGPRA. This line of thinking of going beyond compliance led to a rapid cascade of changes in our daily operations. We refer to this shift in thinking and program for action as descendant community–informed institutional integrity (DCIII). Part of our rationale for structuring our outlook in this way was that the issue of research integrity was something that the scientific community and institutions of higher education had already been thinking about and developing sets of standards to follow (see Mejlgaard et al. Reference Mejlgaard, Bouter, Gaskell, Kavouras, Allum, Bendtsen and Charitidis2020).

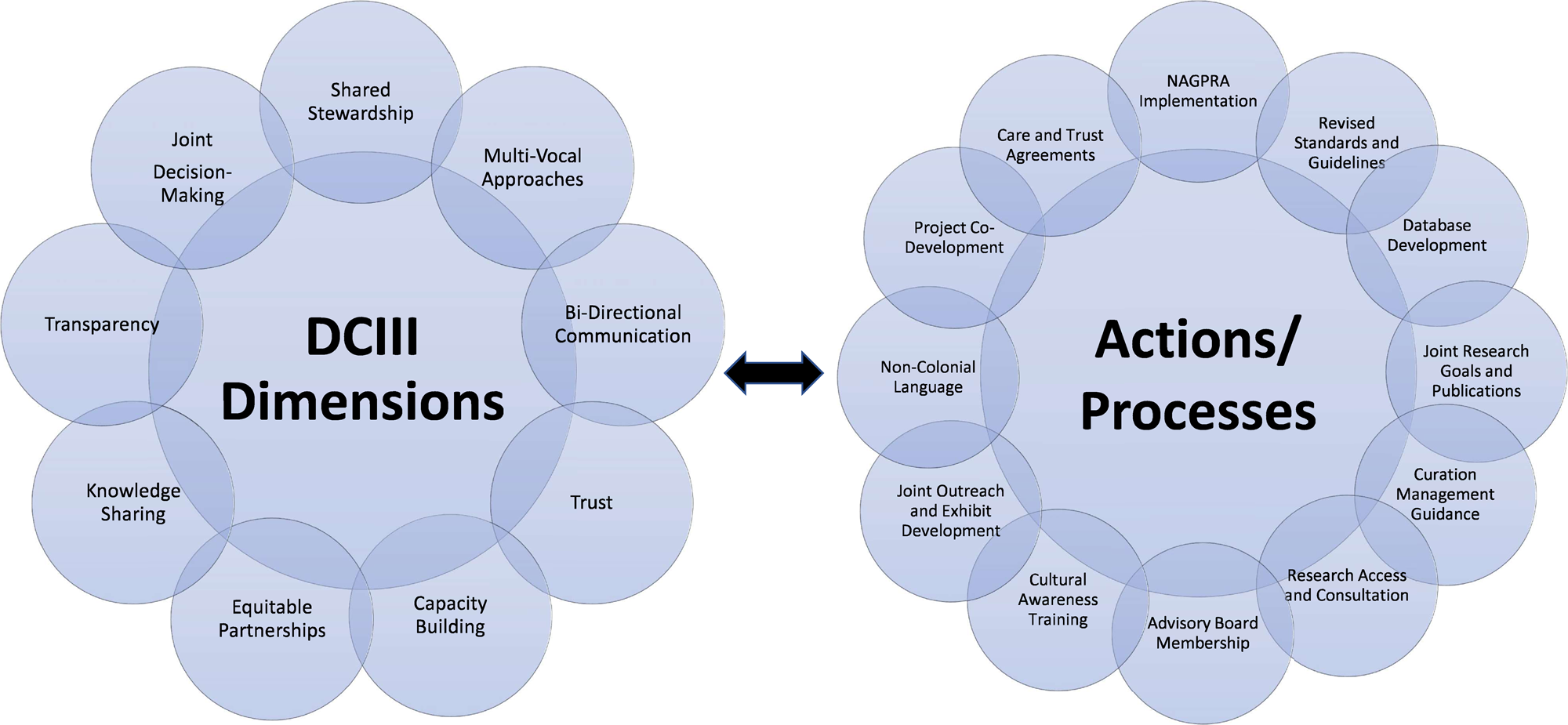

What do we mean by DCIII? DCIII can be thought of as a series of formalized dimensions. These dimensions—shared stewardship, multivocal approaches, bidirectional communication, trust, capacity building, equitable partnerships, knowledge sharing, transparency, and joint decision-making—guide descendant community engagement in policies and procedures within a research integrity program (Figure 1). Consequently, in a sense, DCIII can be thought of as a codified process that works within existing Western university structures to facilitate the decolonization of past practices and policies within a given institution. What this means in practice is examining all the realms in which institutional integrity applies and then evaluating how descendant communities can be engaged in those processes and procedures. For the Laboratory, we came to think about how integrity at the institutional level of a curation repository within a public university could be informed by descendant communities. Our goal for the Laboratory was to build a path toward better community engagement—one that interweaves consultation and collaboration. This path, we felt, would lead us toward better practices in the spheres of research access, public engagement and outreach, language, and curation and collections management, among others. Our thinking on this began with how we could move beyond NAGPRA compliance to a model that incorporates institutional integrity informed by our tribal partners. This all started with NAGPRA collaboration with our tribal partners and our realization that we needed not only more transparency but also a greater understanding on our part that the cultural material held at the Laboratory are deeply connected to contemporary Tribal Nations.

FIGURE 1. Example of dimensions of descendant community–informed institutional integrity (DCIII). Each of these dimensions works toward descendant community engagement so that perspectives are actively incorporated into actions and processes. Figure by Amanda D. Roberts Thompson.

In this article, we first outline how we began thinking about DCIII in the context of our work on NAGPRA, situating these ideas within the broader literature of decolonization. This includes a brief history of NAGPRA at the Laboratory and the extent to which the Laboratory engaged with Tribes in the past and Tribal perspectives on that history. Next, we discuss how we used NAGPRA as a nexus to begin to think about how we could formalize DCIII dimensions in the Laboratory. Importantly, although we were first concerned with changes to our NAGPRA policies, this did lead us to the broader considerations we discuss in this article. In addition, this work also highlights that NAGPRA and Tribal perspectives on other matters are intertwined, and that issues that archaeologists formerly considered to revolve solely around NAGPRA can no longer be compartmentalized as they were in the past. Finally, we discuss the specific realms in which we implement DCIII within the Laboratory, and the ways these articulate with university-wide concerns and can be used by other institutions as a guide to action. Throughout this article, we discuss our missteps and outline the path that the Laboratory took toward a deeper collaboration with the work and the way we care for archaeological cultural materials, Ancestors, and their belongings. Finally, we consider the future of both our institution and other institutions for meaningful collaboration.

Before we move forward with our discussion, we note that the authorship of this article represents members of different federally recognized Tribes, archaeologists, and museum professionals. In part, the article format can be thought of as a microcosm of the future of collaborative archaeology and curation repositories—that is, the “article format” is a Western science structure that carries with it certain constraints. The problem with this is that Indigenous coauthors and Tribal perspectives can be lost in the “et alia” of author lists. Therefore, we include direct comments by our Tribal coauthors that can be highlighted and cited in future works.

DECOLONIZATION, NAGPRA, AND THE UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA

When we began going down this path, the idea of decolonization was certainly at the forefront of our thinking. The Laboratory, like many archaeological units associated with a university or museum, contains cultural materials that archaeologists acquired through a colonial pathway (Colwell Reference Colwell2016; Lonetree Reference Lonetree2012). Decolonization has recently become a more widespread goal, particularly with regard to NAGPRA implementation and changes to museums and other colonial institutions. For example, the Canadian Archaeological Radiocarbon Database (CARD), which is a global database that includes information from the United States, now restricts information on dates run on Ancestors in the database, even if these dates were run prior to the implementation of NAGPRA (see Kelly et al. Reference Kelly, Mackie, Robinson, Meyer, Berry, Boulanger and Codding2022). These dates remain restricted until consultation can resolve a process by which Indigenous communities can be consulted on the process for the release of such information. This is a good example of a path that not only leads toward decolonization but also outlines descendant community engagement on research matters.

Although activists, researchers, and affected communities have called for efforts to decolonize institutions for some time now, recent political and social events have certainly spurred rapid calls to action. And although in some regions there has been a long history of collaboration, other regions—such as the American Southeast—have lagged behind largely due to their deeper histories of genocide and removal of Indigenous people. We believe that the tide is changing with respect to practices beyond compliance. These are practices that are truly collaborative, where Tribal partners and archaeologists are equal partners in research endeavors (see Birch et al. Reference Birch, Hunt, Lesage, Richard, Sioui and Thompson2022). Although individual researchers can and should engage descendant communities in partnered work, it is more difficult for an institution—particularly public academic institutions—to do this in a rapid fashion. The difference is related to both scale and complexity in the endeavor. Certainly, many institutions, particularly archaeological units associated with universities and museums, have made progress toward “decolonization,” but the outlining of such policies and practices can sometimes be difficult for upper administration to articulate with institutional policies. Individuals and their associated institutions may have competing thoughts or standards for what constitutes community engagement, and whereas individual researchers can implement change in their own practices, it is more difficult at an institutional level (such as at a state academic institution) to enact changes in policies and practices that often have to involve outside affiliated institutions (e.g., state government) as well. Yet, academic institutions still have the ability to create opportunities, bring knowledge, and build connections and relationships among descendant communities, organizations, and people.

Although the literature on decolonization (e.g., Atalay Reference Atalay2006; Bryant et al. Reference Bryant, Bryant-Greenwell, Catlin-Legutko, Jennings, Jones-Rizzi and Callihan2017; Lonetree Reference Lonetree2012; Schneider and Hayes Reference Schneider and Hayes2020) certainly provides some useful starting points for thinking about such issues, clear guidance is often in the abstract and theoretical, with only a few direct actionable items (e.g., land return) that are commensurate with the direct authority that archaeological curation repositories within an academic setting can enact. Few, if any, address the complexity of engaging in such actions within such settings. Furthermore, the word “decolonizing” implies that at some point its achievement is possible. Given that most public academic institutions exist within a colonial framework that is deeply embedded within larger political hierarchies—and within the practice of archaeology itself (Schneider and Hayes Reference Schneider and Hayes2020)—we are not overly optimistic that widespread decolonization can happen without larger structural changes within academic institutions. Consequently, although the literature on decolonization provides important ideas to situate action and broader academic discourse, we needed a specific path of operation—that is, something actionable. The Laboratory needed to move beyond NAGPRA compliance and toward decentering archaeology and curation practices, putting institutional integrity that is informed by descendant communities (i.e., source communities or communities first of origin; see Peers and Brown Reference Peers and Brown2003).

General NAGPRA Process versus NAGPRA at University of Georgia

Congress passed NAGPRA in 1990 to create a process that requires all museums (any institution that receives federal funds is defined as a museum and is required to comply with NAGPRA) to repatriate NAGPRA cultural materials that meet the requirements outlined in the law and are claimed by lineal descendants, Native American Tribes, or Native Hawaiian organizations. When NAGPRA was passed, a deadline of November 16, 1995, was announced for museums to submit inventories and identifications. Under NAGPRA, museums must follow a specific process, which includes consultation, compiling information into specific formats, and determining cultural affiliation before repatriation can occur. For example, if there are Ancestors and associated funerary objects within a collection, an inventory must be completed and a Notice of Inventory Completion (NIC) must be submitted. Next, a claim can be made, which is followed by the repatriation of Ancestors and associated funerary objects. For cultural items (i.e., unassociated funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony), a summary and a Notice of Intent to Repatriate must be completed prior to disposition. All steps have to occur in consultation. One of the most important components within NAGPRA is the requirement for consultation with lineal descendants, Native American Tribes, and Native Hawaiian organizations throughout the entire process. Consultation is defined under NAGPRA as “a process involving the exchange of information, open discussion, and joint deliberations with respect to potential issues, changes, or actions by all interested parties” (HR 101-877).

In 1990, the Laboratory, as part of its compliance with this legislation, began creating inventories and summaries and assigning cultural affiliation to all Ancestors and other cultural materials considered to be under NAGPRA. This information was collated into two reports: one report contained information on NAGPRA cultural material that was culturally affiliated, and the other contained information on individuals and cultural materials classified as culturally unidentifiable. These reports were sent to the National NAGPRA office by November of 1995, but no Notices of Inventory Completion or Notices of Intent to Repatriate were submitted. Consultation on the NAGPRA process at the Laboratory seems to have occurred through letters sent a few times between 1992 and 1995, but after these, the Laboratory considered its NAGPRA obligations fulfilled, and no other NAGPRA implementation occurred, with the exception of a 2010 joint repatriation and another repatriation in 2019. As a result, consultation efforts were minimal, were stalled, or never really began.

Beginning in 2019, the Laboratory reevaluated its previous NAGPRA work and realized that it had much more to do. The Laboratory began to understand that although NAGPRA compliance had occurred to some degree previously, there were issues preventing repatriation and disposition. For example, given that there were not any Notices of Inventory Completion or Notices of Intent to Repatriate, Tribes were not able to make claims. Furthermore, the Laboratory had submitted information on all NAGPRA cultural material within the repository, including cultural material controlled by federal and state agencies, rather than only focusing on what cultural material were the responsibility of UGA. Additionally, NAGPRA cultural materials that were originally classified as culturally unidentifiable were later known to be culturally affiliated through Tribal consultation. Last, there were no consultation efforts after 1995. In 2019 and 2021, the Laboratory applied for and received National Park Service NAGPRA Consultation grants. With this funding, the Laboratory now has a reinvigorated NAGPRA program that participates in meaningful collaboration, consultation, and connection across Tribal communities in addition to other state entities and universities.

Tribal Perspectives on the History of NAGPRA and Engagement at UGA and Similar Institutions

Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana (represented by Raynella Fontenot and Linda Langley)

“The Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana Historic Preservation Office was established in 2013. Prior to that time, NAGPRA consultation with the Tribe was virtually nonexistent. Laboratories, museums, and other repositories typically either did not send consultation requests, addressed them to Council members, or mistakenly thought that requests sent to sister Nations, such as Muscogee Creek and Alabama-Coushatta, filled the requirement for consultation.”

Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (represented by Miranda Panther)

“NAGPRA compliance and implementation does not have to be a singular interaction between Tribes and institutions. NAGPRA functions best for all those involved when we move beyond mere compliance by building rapport and working relationships with agencies, institutions, and museums. Tribes can assist in crafting best practices in the care of Ancestors and their belongings, and in creating policies that better reflect Tribal wishes. The history of NAGPRA at UGA is a common refrain among institutions. These regulations were enacted with no standard or guidance on how to produce inventories or summaries. Decisions for creating these documents were left up to individual institutions with no consideration for uniformity, ease of interpretation, or transparency. NAGPRA has also relied on the integrity and ethics of those responsible for the compliance and implementation of the law when some of these individuals have lacked both. As such, NAGPRA is not a particularly punitive law when it comes to noncompliance. Tribes were particularly unduly burdened after the enaction of NAGPRA, as they didn't have the resources in place to deal with the influx of correspondence, along with having to regulate the institutions responsible for compliance. From the perspective of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI), those involved with NAGPRA have made significant progress, and the most successful projects involved agencies who recognize the intrinsic value that Tribes contribute. The work that UGA has performed over the last few years is the standard that we would like to hold other institutions up to. They have set a high standard for Tribal engagement and involvement both in NAGPRA-specific issues as well as more general topics. Tribes are given multiple opportunities to provide input, and UGA provides consistent updates on the status of NAGPRA projects. The staff at UGA are part of a more modern and culturally sensitive movement of professionals working with Tribes.”

Muscogee (Creek) Nation (represented by RaeLynn A. Butler, Turner Hunt, LeeAnne Wendt)

“It has come to the Muscogee Nation's attention that there are more than a few institutions that believed they were compliant only to realize they have a lot of work ahead of them. We have been told in the year 2021 that we should already be in possession of these inventories and summaries because the institution faxed them ‘to the Tribe’ in 1995. It is often disappointing news, and that level of work is clearly insufficient to fully comply with NAGPRA. Additionally, the department began to deal with many collections that were identified by some individuals in the past without consulting any Tribal Nations.

The situation was compounded by the fact that like many laboratories, Tribal Nations were handed the consequences of an unfunded mandate. The Muscogee (Creek) Nation initially established the office in 1995, with Tribal Resolution 95-01, as a direct response to the outreach by some institutions. Tribal Historic Preservation Offices (THPOs) are often inundated with compliance correspondence, and each Nation approached NAGPRA compliance differently. It was not until 2017 that the department created an additional position to focus solely on NAGPRA compliance. While the department has been very proactive with NAGPRA, it has only been within the recent decade that our department had the capabilities to address the enormous load of NAGPRA cases. Luckily, laboratories, such as UGA, have shifted to a more collaborative process that has continued to build trust between the Laboratory staff and our department. The burden no longer falls on the Tribe or Laboratory alone; with the collaborative process, the partnership approaches the caseload with respect and understanding.”

Seminole Tribe of Florida (represented by Domonique deBeaubien)

“The stalled progress of NAGPRA at UGA unfortunately is not unique. It's fairly common for the Seminole Tribe of Florida to become aware of institutions that are out of compliance or have not made any repatriation effort since the early ’90s. We are aware of thousands of Ancestors and sacred objects awaiting repatriation while institutions work to complete inventories, conduct consultation, and submit Notices of Inventory Completion. While it can be frustrating to learn of this over 30 years after the passage of NAGPRA, we are always glad to work with institutions with reinvigorated staff trying to do the right thing.

The UGA team has taken great steps to begin building a meaningful partnership. We have consulted beyond NAGPRA cases and provided comments on how to best shape the department moving forward. There is a great deal of work left to do, and we look forward to seeing it through with our university and Tribal partners.”

NAGPRA AS A NEXUS

As a starting point, it is important to explore the nature of NAGPRA, how archaeologists have typically conceptualized the law, and how it relates to practice. After its passage, it is fair to say that many archaeologists in North America felt that this was the end of research on certain aspects of the archaeological record—in essence, an end of knowledge of one aspect of Native American lifeways. Some archaeologists even decried the law itself as the end of science and a “bad law” (Clark Reference Clark1999:48). This, of course, did not turn out to be the case. This line of thinking was predicated on implicit belief illustrated by Vine Deloria Jr.'s (Reference Deloria1973:33) often-quoted observation that “real Indians” only lived in the past (see McGuire Reference McGuire, Biolsi and Zimmerman1997:63). In fact, our tribal partners point out that they see a distinction between those who embrace NAGPRA and those who cling to a more pre-NAGPRA way of thinking about archaeology, the latter usually rooted in Western science rationalization for the study of Native American histories (see McGuire Reference McGuire, Biolsi and Zimmerman1997). This has been the experience of the directors of the Laboratory as well, who at various times received unsolicited advice from senior archaeology colleagues that contradicts Tribal perspectives. This is not to point fingers or cast dispersions on any one person or institution. It is merely to point out that there is still work that needs to be done, and that there continues to be a lingering subtext in the American Southeast.

This way of thinking focuses on a past in which there lived people who were fundamentally different from the descendant Tribal Nations living today. Nothing could be further from the truth. The forced removal of Indigenous people that meets the definition of ethnic cleansing, heinous land treaties resulting in stolen land, and archaeological narratives that emphasize sterile chronologies and discontinuities in social and political traditions continue to reinforce the notion of a remote and separate past. These historical narratives only serve to continue to erase Native peoples from their past, and unfortunately, some institutions still cling to these colonial ideals.

As argued by Schneider and Hayes (Reference Schneider and Hayes2020), a decentered and decolonized archaeology is one that focuses on Indigenous survivance and the continuity of Native voices rather than colonial narratives of erasure and discontinuity. How, then, do we move forward as an institution in this regard? How does the Laboratory stay above the delusion of a disconnected past and the false colonial narrative of the disappearance of Indigenous people in the present (Schneider and Hayes Reference Schneider and Hayes2020)? Moreover, how can the work we do at the Laboratory incorporate and support Indigenous beliefs, perspectives, and histories? In other words, how can we do work that is for the “benefit of Indigenous people, communities, and sovereignty” (Schneider and Hayes Reference Schneider and Hayes2020:132) rather than simply focusing on producing knowledge for the “consumption of Western public and scholarly audiences” (Atalay Reference Atalay2006:283)?

We believe that part of the answer to this question lies in developing deep collaborations with our Tribal partners and moving beyond simple compliance with NAGPRA (see Neller Reference Neller, Warner and Terry Childs2019). Curation repositories and the wider field of archaeology cannot exist in a vacuum anymore. It is imperative that we all engage with descendant communities, collaborate in actionable ways, and ensure that this type of parallel engagement becomes a normalized part of curation practices. This meaningful engagement can be manifested into examples of actions/processes highlighted in Figure 1 and can take the form of traditional care practices, incorporation of traditional knowledge (i.e., TK labels), shared web portals for access to information, joint outreach programs or exhibits, and publications, among many others. In short, DCIII is the active exchange of ideas and the development of mutual respect that centers on correcting past mistakes and views within archaeology.

In considering the continuum of compliance to integrity, one starting point for institutions to think about is using NAGPRA as a nexus to move beyond simply doing what is required by law. More to the point, it is important to remember that NAGPRA is part of human rights legislation. Understanding and being sensitive to the differences outlined above and the basis of NAGPRA are the first steps in decentering a “compliance” relationship where Tribal Nations are seen solely as regulators in NAGPRA. Although, of course, Indigenous culture plays a part in different views of NAGPRA, these views are not homogenous among Native Americans, and to treat them as such is yet another settler-colonial perspective. Consequently, although the end result of NAGPRA is repatriation, how various tribes view the “NAGPRA journey” varies, and this needs to be taken into consideration by repositories.

Compliance relationships not only often set up antagonisms between different groups of people but also focus on what “must be done” rather than what “should be done.” This focus on compliance then tends to take the form of top-down directives, which may or may not involve Laboratory staff or students. This, of course, is important because tribes have a government-to-government right to consultation, and those at the table should be the decision-makers and the leaders of the federal agency or institution. Therefore, often the only time Laboratory staff or students are involved with Tribal consultation or collaboration in their daily work is if they are directly involved in a NAGPRA project. This means that there are fewer opportunities for staff or students within their daily work or school lives to view what they are doing as being connected to contemporary Tribal Nations, further discouraging meaningful collaboration with Tribes. Given that most Laboratory staff or students are at the start of their careers, this further reinforces the idea of a disconnected past to the next generation of curators, museum professionals, and archaeologists.

Instead of only focusing on the accepted definitions of “compliance” or “ethical considerations,” we opt to consider a DCIII approach that centers on high integrity through robust Tribal engagement and consultation. Therefore, instead of thinking about what must be done, we act on things that should be done, and we develop policies and procedures that follow suit. What this means is that compliance is met and exceeded, but the way this is accomplished also provides important steps in moving the sum total of practices toward something that is guided by tribal input and that leads to high research and collections integrity standards. In contrast to a top-down approach, cultivating research and curation integrity through DCIII engages people involved in non-NAGPRA as well as NAGPRA-related activities, from students to curatorial staff to directors. By approaching policy and practice in this way, DCIII not only permeates all aspects of activities but also provides an opportunity for everyone to contribute to building better practices for those activities.

Tribal Perspectives on NAGPRA as a Nexus

Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana (represented by Raynella Fontenot and Linda Langley)

“Our Tribe's meaningful collaboration with the Laboratory began with a telephone call in which the principals apologized for past attitudes and behaviors related to NAGPRA consultation. This approach was entirely unprecedented in our experience and served to immediately move us from the antagonistic and adversarial mode of interaction we had come to expect in NAGPRA consultations. From that point forward, we have been invited to participate fully and provide opinions on all topics, ranging from the way data and files are shared to policies and even record-keeping procedures. Significantly, this collaboration has served to establish a ‘new normal’ in our expectations for future consultations.”

Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (represented by Miranda Panther)

“Tribes have historically been prevented from contributing to policy creation on topics that directly affect them. UGA is giving us a seat at the table when it comes to NAGPRA and related issues. We are forging a mutually beneficial relationship through our collaborative efforts. These efforts have far-reaching positive outcomes, as Tribes are subject matter experts on the topics of cultural knowledge and traditional beliefs, as well as a number of other subjects interconnected to the implementation and practice of NAGPRA. Working with Tribal partners increases and encourages cultural sensitivity among professionals working in the field and affects change in an affirmative way that is inclusive of descendant communities. It is also imperative that Tribes can work with people such as UGA to help create policies and procedures that focus on invaluable Tribal input.”

Muscogee (Creek) Nation (represented by RaeLynn A. Butler, Turner Hunt, LeeAnne Wendt).

“The concept of NAGPRA as a nexus is a thoughtful way to turn implementation of federal law into meaningful relationships. The relationships extend past what is simply required by law and create a system that benefits the Laboratory, institution, and Tribal Nation. The process of building rapport with descendant communities is a necessary step every laboratory should take to ensure future collaborations. There are two tracks of compliance. One, being a strict adherence to only what is required, will be marred in difficulty because the institution and Tribes are simply strangers attempting to negotiate the release of their Ancestors. The one prescribed herein is built on mutual trust, respect, and a shared vision of the future where researchers and descendant communities work together toward better outcomes than in the past.

Although many institutions embody the spirit of the law today, we still face underlying feelings of resistance and opposition to NAGPRA claims and reburials. However, we also see progress in terms of attitudes, acceptance, implementation, and support from NAGPRA practitioners today. There seem to be generational differences on the academic side, and more recently trained anthropologists are more accepting and open to collaborative relationships with Indigenous communities, from our experience.”

Seminole Tribe of Florida (represented by Domonique deBeaubien)

“While NAGPRA began as a legal nexus that required institutions to initiate steps to repair grievous cultural injury to Native American Tribes, the shift we are beginning to see is institutions focusing on what can be done to help repair this damage. Tribal members are facing generations of cultural harm caused by colonialist attitudes toward excavation and collection practices, while many museum professionals are left holding the bag, trying diligently to right wrongs they themselves did not create. Only through working together, as respectful allies of repatriation, can we begin to heal this harm on both sides.

Implementing NAGPRA presents many challenges—not just for museums and federal agencies but for Tribes. Tribes face the same dearth of funding and resources, and have the additional challenge of being overburdened by the sheer number of incoming consultation requests under federal law. The Seminole Tribe of Florida Tribal Historic Preservation Office (STOF-THPO) received over 1,700 requests for consultation in 2021 alone. These numbers are not unique to STOF-THPO, yet Tribes still find a way to the consultation table to see their Ancestors home. Consultation presents its own set of unique challenges, with many agencies unaware or unwilling to hold meaningful discussions. Tribes spend countless hours having to justify who they are and why their beliefs are valid, and face the cruel expectation of having to prove who their Ancestors are. Oral histories and Native traditions are not given equal weight to conventional histories published in scholarly books and articles, which places Tribes on unequal footing during consultation.

For those looking to implement NAGPRA today, building long-lasting and meaningful relationships with Tribes will start to break down many of these obstacles. The more allies within museums who take the time to listen, understand the power behind Tribal histories, and implement policies respectful of Native traditions will help make repatriation a less harmful process for everyone. Developing meaningful consultation practices is more than just checking a box or sending a letter. It involves time, commitment, perseverance, and being open to learning new ways of thinking, doing, and knowing. We are always glad to be a part of an agency's learning process, and hope to share this knowledge with others.”

STARTING DOWN THE PATH TOWARD DESCENDANT COMMUNITY–INFORMED INSTITUTIONAL INTEGRITY (DCIII)

As we mentioned previously, starting down the path to DCIII requires deep collaboration with descendant communities. This does not happen overnight, and it requires building rapport and demonstrating trust. There can be a temporal fragility to relationships, and there are definite “challenges for communities, researchers, and museums not only to keep relations active as participants shift over time but also to find new ways to expand the scale and scope of these networks” (Bell Reference Bell2017:253). The point here is that even with potential difficulties with descendant community communication, such conversations can transform institutional processes regarding research and everyday practices that are driven by integrity and ethical engagement, thereby providing mutual benefits to descendant communities, the public, and academia. Again, for us, this path started out as one focused on NAGPRA compliance. When we realized that NAGPRA practices were lacking at the Laboratory, we began reaching out to federally recognized Tribes. This started out as simple phone calls and emails. Our purpose during these phone calls was to make everything in the Laboratory transparent, outlining the state of NAGPRA in the Laboratory and all that still needed to be done. In our conversations with Tribes, transparency about the Laboratory's complete history—not just its failings with NAGPRA—was important. Our goal in opening up this history was to establish a relationship with Tribal communities based on trust and respect. Although we have made progress in engaging Tribal communities who have ancestral connections to the cultural materials within the Laboratory, we still have work to do.

Another aspect of this work that became clear in early conversations is that Tribal communities have a more encompassing view of cultural materials than the traditional ways in which archaeological laboratories and curation repositories viewed their roles vis-à-vis NAGPRA. The key difference between these two views is that the Laboratory viewed NAGPRA cultural material in our repository from a compliance perspective, whereas Tribes took a more holistic view that included their own cultural beliefs. The question then became how the Laboratory would match these perspectives in action and regularized practice. Through our conversations, we realized that we needed a complete reevaluation of all Laboratory activities, from policies to the daily practice of curation and collections management, and to then vet those activities and policies with Tribal communities. How could we bring the ideas of our tribal partners into the Laboratory in a meaningful and sustained way that could easily be understood and adopted at all levels of the Laboratory, from student employees to the directors?

Our goal was to have the Laboratory operate on a daily basis with practices rooted in DCIII. Although space constraints prevent us from discussing all dimensions of DCIII (see Figure 1), we do want to highlight the dimension of transparency. Descendant communities need to be aware of activities within the Laboratory—not just the day-to-day activities but also future projects. To do this, it is essential that there be descendant community representation in decision-making and cooperative planning. For us, at first this meant implementing policies and procedures within the Laboratory that we had the direct authority to implement but doing so with Tribal community input.

Through these conversations, the Laboratory created NAGPRA policies (which had not existed previously) and revised its collections management policy (SI 1-2). These policies are now guided by advisory boards consisting of descendant community representatives, Laboratory directors, and university faculty. Concurrent to the development of policies created through collaborative conversations was the reassessment of standards that structure daily practice within the Laboratory. Among others, this included standards for NAGPRA work in addition to general artifact processing. Whereas previously the Laboratory had zero relationships with Tribal descendant communities, there are now bimonthly updates sent to Tribes that have ancestral homelands in Georgia, and there are frequent phone calls and emails between the Laboratory and its primary Tribal partners. Overall, there is an “open door” philosophy—that is, we aim to be available for any and all communication. These actions are all geared toward making the Laboratory operate with integrity by having ongoing and transparent conversations with our Tribal partners, listening to them, and seeking advice on how to best operationalize their ideas within the Laboratory. These partnerships have directly allowed for the incorporation of tribal perspectives on not just NAGPRA implementation but also all activities within the Laboratory.

Tribal Perspectives on Institutions and Relationship Building

Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana (represented by Raynella Fontenot and Linda Langley)

“As a small Nation with a history characterized by voluntary movement rather than forced removals, the Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana has often been overlooked in historical, archaeological, and ethnological records. Engaging in DCIII-based consultation has provided us with an opportunity to share Tribal history, traditional knowledge, archaeological evidence, and other information that had previously been missing from the ‘official’ record.”

Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (represented by Miranda Panther)

“The EBCI has been pleased and encouraged by the changes made at the Laboratory as a result of extensive conversations with Tribal partners. Being able to contribute to shaping policy at the Laboratory, as well as educating the staff about cultural topics in a Tribe-centric manner, has resulted in positive effects in the NAGPRA world. UGA has been transparent and communicative in its efforts to collaborate with Tribes. The monthly calls and frequent updates help Tribes stay aware of the progress made and any potential issues. The productive relationship that the EBCI experiences with UGA is one that is based on respect, ethics, integrity, and reciprocity. This, of course, isn't required by the NAGPRA regulations, or even to be compliant with NAGPRA, but it goes a long way towards fulfilling the moral obligation that the EBCI associates with NAGPRA work and honoring our Ancestors and their belongings.”

Muscogee (Creek) Nation (represented by RaeLynn A. Butler, Turner Hunt, LeeAnne Wendt)

“There are a number of Mvskoke values that are important to discuss in terms of NAGPRA. Vrakkueckv means respect—and it is what we show to our Ancestors, what we expect from Laboratory staff for our Ancestors, and our claims. Fvtcetv means integrity—and is what we expect from institutions with NAGPRA collections, to admit the shortcomings of the past and move forward. Mecvlke means responsibility, and the department's ultimate responsibility is to seek out, find, and repatriate our Ancestors, while the Laboratory's responsibility is legal, ethical, and moral. All of these values, and more, are understood after developing deep relationships with DCIII. The building of rapport between the groups involved in NAGPRA allows thoughts, ideas, and culture to be shared in ways not defined by the law, regulations, or policies.”

Seminole Tribe of Florida (represented by Domonique deBeaubien)

“Relationship building should serve as the foundation to any institution that conducts consultation with Native American Tribes. Consultation should always be free, prior, and informed so that Tribes are not just invited to the table but play an active part in the decision-making process. Consultation is greatly hampered if there is distrust of an institution, and forging respectful and transparent relationships can help to combat this.”

DCIII AS POLICY AND PRACTICE

For the Laboratory, there are a number of different dimensions of DCIII that can inform the following: research access, education and public engagement, curation and collection management, databases, and engagement with upper administration. Due to space constraints, we do not list everything, and it is likely that there are other dimensions that we have not yet thought about. Nevertheless, we outline some of the starting points and critical actions that we instituted or are in the process of enacting to bring the Laboratory more in line with these ideas. Although many of these changes do involve NAGPRA to one degree or another, they represent systemic changes that now incorporate Tribal voices in all aspects of Laboratory management and policies.

Research Access

Based on early conversations, it became immediately apparent that research processes needed to be reevaluated. Our conversation about research started with NAGPRA but soon addressed how to incorporate consultation on all cultural material curated at the Laboratory. However, not all curated collections are under the university's control; much of the cultural material is under the purview of state and federal agencies. Those authorities (e.g., US Army Corps of Engineers) have the ultimate say regarding research. This means that decisions regarding research and access cannot be unilaterally made by us for that cultural material. Rather, it must be made not only in consultation with Tribes but also with those state and federal agencies. To begin these conversations, the Laboratory hosted a large meeting attended by Tribes and state and federal agencies. One thing that we all quickly agreed on was that research on Ancestors and NAGPRA cultural materials is prohibited (including but not limited to photographs, analysis, and publications) unless there is express and written consent by the controlling agency and culturally affiliated Tribe(s), as outlined in the Free, Prior, and Informed Consent in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights).

The result of this meeting was a workflow for research requests that incorporates consultation with Tribes. Given that the Laboratory gets numerous requests from researchers and students throughout the year, we need to consider the time constraints on Tribal communities and the Laboratory. In order to create a streamlined review process for decisions regarding support for research, we codeveloped a consultation research request form that all researchers fill out. By codeveloping this generalized form and implementing a process by which this is sent to Tribal communities to review with agreed-upon timelines, we enable the Laboratory as an institution to continue with its mission in promoting research while simultaneously holding it to higher standards than what is the norm for research access. Together with the Tribes and the other state and federal agencies, we decided that all research must now go through a consultation process. This was something that the Laboratory had never considered in the past. The added benefit to implementing this across all cultural material is that this process creates a network of connections between Tribal communities and state and federal agencies, as well as with the researcher making the request.

Language

Another point of conversation between the Laboratory and Tribal partners is how to incorporate shifts in language from terms that are colonial and problematic in nature to terms that are more humanizing. In our ongoing discussion with Tribal communities, we have found that certain words that are common in archaeology are used without consideration in everyday practice. Certain terms that are common in archaeology are considered by Tribal communitiers to be insensitive to their cultural concerns and practices, which only further distances Tribal communities from their histories. We are, of course, not the first to realize this, and one can find examples from other institutions, such as the list provided by Watson and colleagues (Reference Watson, Young, Garcia-Lewis, Lucas and Plummer2022:145) and as outlined by Davis and Krupa (Reference Davis and Krupa2022). Although some language shifts such as those outlined in Table 2 are widely applicable, institutions need to have direct conversations with descendant communities with ties to the cultural materials that repositories hold, because there can be a difference in terms of practices and perceptions about language. Table 2 provides just a few examples of recent language changes we are beginning to make in the Laboratory. It is important to point out that this list is dynamic and has the potential to change as time goes on. In terms of changes, making shifts in certain language is an immediate and substantive way to begin to alter practice and train the next generation to be more inclusive and respect DCIII.

TABLE 2. Examples of a Few Language Shifts at the University of Georgia Laboratory of Archaeology.

Curation and Collections Management

One focus of conversations with Tribal communities has been about how to incorporate Tribal perspectives and decision-making into the curation of the cultural materials at the Laboratory. One point made by Tribal communities revolved around the respect of cultural materials, with a specific emphasis on the care of NAGPRA cultural materials. As a repository, we maintained certain curation standards—such as temperature and humidity levels and levels of security around how cultural materials were regulated—but we realized that, in general, it was the bare minimum. We decided that one way to make curation and collections management more transparent was to make available to our Tribal partners all of the forms we use, from loan forms to destructive analysis forms and the creation of care and trust agreements. We also sought input on the Laboratory's general standards of archival processing, standards around the rehousing of cultural material, and most recently, standards regarding bundling. These conversations focused on wording and ensured that concerns from Tribes were incorporated into the forms and standards.

For example, as a result of conversations, it is now part of general collections management standards whenever a box is accessed—regardless of the reason—to assess faunal materials for Ancestors, identify potential NAGPRA cultural material, and flag for review and consultation any box that might contain NAGPRA cultural materials. Additionally, prior to any rehousing of a particular collection, research occurs on the site history and contexts to make informed decisions about NAGPRA or any larger cultural concerns that Tribes may have regarding material from cultural sites. This has allowed us to have a more complete idea of which collections contain NAGPRA cultural materials and to identify potentially sensitive cultural materials, whether or not they fall under NAGPRA.

One of the first tangible results of these conversations was to improve how we took care of Ancestors and other NAGPRA cultural materials. Although to some extent we have always had a space for Ancestors and NAGPRA cultural materials, we recently had the opportunity to renovate a separate space dedicated to this. We included Tribal input on the overall design and layout of the renovations, doing our best to accommodate changes and suggestions to make this space one that is commensurate with not only tribal concerns but also the safety and security parameters of the university. This room also contains a consultation room and a space large enough to reunite Ancestors with the objects they were buried with, along with any specific traditional care requested by the Tribe(s) until repatriation and reburial can occur. Through consultation, we decided on a new name for this space. Previously called “special collections” (a problematic term), this space is now referred to as the “Reverential Area.”

Overall, the Laboratory now has stricter rules about access to NAGPRA cultural materials, as well as how those cultural materials should be handled and by whom. The Laboratory also accommodates and encourages incorporation of traditional care practices whenever possible. However, this also applies to how we think about all the collections as a whole. This line of thinking therefore encompasses a whole host of practices that may include, for example, special bundling of NAGPRA cultural materials if requested to do so, traditional ceremonial activities, decisions about when specific genders should or should not handle cultural material, or simply the words we use to talk about ceramics (e.g., Indigenous ceramics instead of prehistoric ceramics). All of these shifts in our thinking that are now implemented in our practices, website, and documents were done in consultation with input from Tribal communities.

Database

Conversations with Tribes about database structure, language, access levels, and security have been ongoing, and with funding from the 2019 and 2021 NPS NAGPRA Consultation grants, the Laboratory is in the process of working with a database developer to create a NAGPRA-specific module within the wider Laboratory collections management database. This database will not only facilitate the rapid export of data, such as inventories for NAGPRA implementation, but also allow the Laboratory and Tribes to manage and protect digital NAGPRA data, such as PDFs, media, and other files. This means that these files can be managed securely so that only people with specific access can view the files. Tied to this is flagging all digital information that is NAGPRA—for example, by identifying and flagging media and other document files that contain NAGPRA or other problematic imagery. Beyond NAGPRA, the Laboratory is working with Tribes regarding issues such as (1) how general site data is stored in the database, (2) artifact typologies and naming conventions, (3) who has access, (4) the flagging of sensitive information, (5) and Tribal concerns regarding specific sites.

Georgia Archaeological Site File

Another ongoing conversation about cultural materials concerns identifying information within the Georgia Archaeological Site File (GASF). The GASF is the official repository for all known data about cultural sites of all periods in Georgia, and it houses information on over 60,000 sites and curates over 16,000 cultural resource management reports. One current project is assessing each site form and creating an inventory of all cultural sites that mention Native American burials or potentially contain cultural material that would fall under NAGPRA. Concurrent to this, the Laboratory is creating a separate inventory of archaeological site names that are culturally insensitive. Once these inventory lists are complete, the Laboratory will consult with Tribal communities to determine the next steps. For example, one step may involve changing inappropriate site names and having Tribal communities rename sites that have inappropriate names.

Staff and Student Training

Training of staff and students is also an ongoing conversation. Tribes have encouraged the Laboratory to take a more proactive approach to the training of students. The Laboratory has many undergraduate and graduate students who either volunteer, take classes, have internships, or work as employees. All students, as part of initial training prior to internships or employment, are required to complete a series of readings and videos covering curation, collections management, and NAGPRA policies, in addition to watching previously recorded lectures from the Laboratory's 2021 lecture series. These lectures centered on archaeological practice, but Tribal discussants were involved to present a Tribal perspective. They are now used to help our students and staff so that they are better informed about Tribal perspectives on archaeological practice, which then guides their work and behavior. We also stress in everyday training the importance of collaboration and engagement, and how that intertwines with whatever project they might be involved with. As a result, students are actively aware of Tribal concerns with projects they are working on. For example, it is not uncommon for students to immediately bring to the staff's attention a bag marked “burial” or to ensure that the faunal remains they are rebagging do not contain Ancestors.

Public Engagement and Outreach

It was—and still is to a large degree—common for archaeologists, in the context of education and public outreach, to share Indigenous knowledge and/or images of burials or funerary objects without consultation. Our Tribal partners stressed early on that such practices not only were unacceptable but also cause harm. The Laboratory does not regularly share artifact images on social media, but now when we do, we carefully scrutinize all posts to make sure that they conform to our integrity standards (e.g., no funerary objects or negative posts). We also now try to be more inclusive in our posts by not only evaluating post content prior to posting but also doing joint posts with our Tribal partners.

Another immediate change that the Laboratory incorporated related to public outreach was the way we present tours. For example, the Reverential Area is not part of visitor tours. Another change was ensuring that images and information on NAGPRA cultural materials are not used for outreach activities or social media. One specific example is that prior to conversations with our Tribal partners, several funerary objects were 3D scanned, printed, and painted, and they were commonly used in classes, outreach, and tours. These objects have been removed from such use, and we are now determining through consultation whether they should be repatriated along with the NAGPRA cultural materials from those cultural sites. One other focus is incorporating discussion from our Tribal partners about the living culture of Tribes instead of learning by objects alone. As we move forward and develop more public programs, we plan on sending all outreach activity plans to our Tribal partners for review and suggestions prior to implementation.

Another major change involves our publicly accessible website and digital resources related to the UGA Lab Series, a series of reports that are accessible to the public. However, many of these Lab Series contained images and drawings of NAGPRA cultural materials. All Lab Series that contain such images and drawings have now been redacted, and each document now contains a warning label to ensure that the reader is aware of the sensitive content. This same methodology is now being applied to other digital documents that the Laboratory has on file. This means that the Laboratory and Tribal communities have the option to view or share redacted or unredacted versions of files depending on their preferences.

Institutional Change

All the changes that we are making at the Laboratory set a standard for the university as a whole. The way the Laboratory operates—our policies, practices, and procedures—can serve as a model for other units on campus. One thing that we have learned is that it is not enough to simply serve as an example; this must be communicated on a regular basis so that the university community as a whole understands the importance of these changes and the incorporation of tribal perspectives. We work closely with the University of Georgia Office of Research, our provost, and the Office of Research Integrity and Safety regarding the work that we do in the Laboratory. Through these conversations, we have been able to cultivate a relationship with upper administration. In addition to being informed about the importance of our work, these offices rely on the Laboratory for advice and collaboration when crafting larger university policies. For example, the Laboratory is involved in writing policies and procedures regarding university-wide NAGPRA policies. Moreover, it is largely through such collaborations that we are able to help foster a community of university-wide institutional integrity with regard to descendant communities and their histories. As we look to the future, we are committed to an ever-evolving relationship with Tribal descendant communities that centers on the pursuit of best practices in curation and collections management, research, educational and outreach activities, and collaborative engagement.

Tribal Perspectives on Descendant Community–Informed Institutional Integrity

Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (represented by Miranda Panther)

“The staff at UGA have been very receptive to changes we have asked for, including a person's first preference when it comes to the terminology used. For example, using the word Ancestor instead of human remains. It may seem like a small change, but it sends a powerful message. An area that UGA has excelled at when it comes to Tribal interests that are not strictly NAGPRA-related are research requests. UGA has incorporated the EBCI Treatment Guidelines for Ancestors and Funerary Objects, which covers survey, excavation, laboratory/analysis, and curation standards in their policies and procedures. These guidelines prohibit photography, image publication, and research without explicit Tribal approval and permission. They also do not allow research on any NAGPRA-eligible collections, whether they are under active claim or not. Another way in which UGA has involved Tribes is by inviting them to design displays with Tribal representation at UGA, as well as contributing to interpretive projects. We have participated in numerous presentations, public outreach, and educational events that UGA has hosted. They have also included our input and approval of social media posts, which reach a large audience. These opportunities only serve to strengthen the symbiotic relationships that can be accomplished between institutions and Tribal partners.”

Muscogee (Creek) Nation (represented by RaeLynn A. Butler, Turner Hunt, LeeAnne Wendt)

“NAGPRA creates, among many other things, opportunities to share knowledge. The benefit of institutions involving Tribal Nations is that if one considered that before NAGPRA, there was not even a chair at the table for most Tribes. Decisions regarding the future disposition, curation, and overall treatment of their Ancestors were made without them. The re-establishing of partnerships through consultation has provided not just a seat at the table but the ability to advocate for policy that is culturally respectful and designed collaboratively. While benefiting laboratories, we have benefited from being a part of the process—mostly from the inclusion in an area where we have been historically excluded.”

Seminole Tribe of Florida (represented by Domonique deBeaubien)

“Tribes should be at the forefront of decision-making for how their Ancestors are treated prior to repatriation. Instilling a collaborative process from the ground up will help Tribal voices be heard. Rethinking how we do research—the questions we ask and the projects we undertake—is a vital step in overcoming colonialist norms established by the founders of archaeology. Creating an inclusive and respectful research environment should be at the forefront of every institution with Native American collections.”

CONCLUSIONS: FROM NAGPRA TO DCIII

Above, we document our transition to a DCIII-centered approach with respect to NAGPRA compliance but our journey is ongoing, and we hope that the Laboratory will always retain this evolving and multivocal flow regarding the input of Indigenous perspective and knowledge. However, what we have outlined here is not necessarily novel. Many other institutions to some degree or another operate under similar ideologies or methodologies and use collaboration and descendant community engagement in their daily practices (see the following for a few recent examples: Barnes and Warren Reference Barnes and Warren2022; Bazan et al. Reference Bazan, Black, Thurn and Usbeck2021; Goff Reference Goff, Warner and Childs2019; Goff et al. Reference Goff, Chapoose, Cook and Voirol2019; Krupa and Grimm Reference Krupa and Grimm2021; Marsh Reference Marsh2022; Richardson et al. Reference Richardson, Posas, Posadas and Bardolph2017; Nash and Colwell Reference Nash and Colwell2020, Reference Nash and Colwell2022; Nicholas Reference Nicholas2022; Punzalan and Marsh Reference Punzalan and Marsh2022; Sievert and Ryker-Crawford Reference Sievert, Ryker-Crawford, Barnes and Warren2022; Teeter et al. Reference Teeter, Martinez and Lippert2021; Wheeler et al. Reference Wheeler, Arsenault and Taylor2022; Windchief and Cummins Reference Windchief and Cummins2022). It is our hope that adding our experience thus far to the conversation can provide some examples that can be implemented at other institutions. We suggest starting with initiatives (not necessarily NAGPRA) that can be centered on DCIII. One pathway toward research and curation integrity is for institutions to first recognize that policies and practices need to be developed with deep collaboration in mind—given that cultural material is part of Indigenous intellectual and cultural property and therefore integral to Tribal sovereignty—and then begin changing policies and practices accordingly. In general, institutions with cultural material should regularly engage different types of groups (federal, state, and the public) through such activities as curation, research, training/education, public outreach, and stewardship. This situates these institutions in a unique position to shift the paradigm toward a better future.

Tribal Perspectives on the Future

Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana (represented by Raynella Fontenot and Linda Langley).

“DCIII gives each Tribe and consulting partner an equal seat at the table. This is a consultation model that allows us to finally move forward with respectful repatriation and reburial of our Ancestors and their belongings. DCIII also provides us with a new way to move beyond ‘Colonial’ and ‘post-Colonial’ frameworks into new ways of interacting and sharing information, so we can make meaningful and lasting changes for future generations.”

Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (represented by Miranda Panther)

“NAGPRA was created and enacted with little to no Tribal input or representation. This same Tribal exclusion has persisted through the development of inventories and determinations of cultural affiliation. With the cooperation and collaboration of institutions such as UGA, Tribes are making headway in advocating for more inclusion and consideration. It is the hope of the EBCI that more institutions will follow the lead of UGA and their progressive and equitable NAGPRA policies will become the standard of practice in the field of practitioners. By working together, we can more easily accomplish the solemn and honorable goal of the reburial of our Ancestors and their belongings.”

Muscogee (Creek) Nation (represented by RaeLynn A. Butler, Turner Hunt, LeeAnne Wendt)

“The Muscogee Nation's goal is the respectful repatriation and reburial of our Ancestors and their belongings. We are committed to assisting repositories at various stages of NAGPRA implementation to achieve compliance with the law, but we ultimately seek to establish meaningful relationships with archaeologists and NAGPRA practitioners to work toward building a more inclusive environment that includes descendant community–informed institutional integrity.”

Seminole Tribe of Florida (represented by Domonique deBeaubien)

“The work of repatriation will be ongoing for generations to come. We measure our success not in victories, but in moving the needle a little bit forward, or setting the bar a little bit higher with our institutional colleagues. Relationship building is a huge part of our successes, and we hope through these meaningful partnerships to see Native Ancestors and their belongings returned home.”

LOOKING FORWARD

With the help of our Tribal partners and advisors, the Laboratory has shifted both its policies and practices to include descendant community engagement in a substantive way. That said, the Laboratory still has a long way to go and is still learning how to better integrate community concerns within the broader confines of the university system. To that end, we have now begun conversations and engagement with African American communities who have cultural ties to the archaeological collections in the Laboratory. Our processes and commitment to inclusion with other descendant communities will follow the same model that emerged from our Tribal partnerships. Such engagements enhance our ability to be a more conscientious Laboratory that centers on people and their histories and not merely the objects of scientific study.

Acknowledgments

This work would not have been possible without the great relationships with various individuals from the Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana, Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, Muscogee (Creek) Nation, Seminole Tribe of Florida, and others whom we have consulted and worked with the last few years. We would also like to thank Chris King of the Office of Research Integrity and Safety at the University of Georgia for the conversations about research integrity at UGA. We would also like to extend thanks to the University of Georgia Department of Anthropology, Franklin College of Arts and Sciences, and the Provost Office for the continued support of the Laboratory's NAGPRA program. Finally, we would like to thank the Laboratory staff and students who strive to make the Laboratory a place of respect and integrity for descendant communities. No permits were required for this research.

Funding Statement

No grant funding was involved in the preparation of this article.

Data Availability Statement

All collections referenced herein are curated in perpetuity at the University of Georgia Laboratory of Archaeology. All inquiries regarding access to these collections can be addressed to the director of the Laboratory of Archaeology. Contact information is available at https://archaeology.uga.edu/archlab/people.

Competing Interests

There are no competing interests to the best of the authors' knowledge.