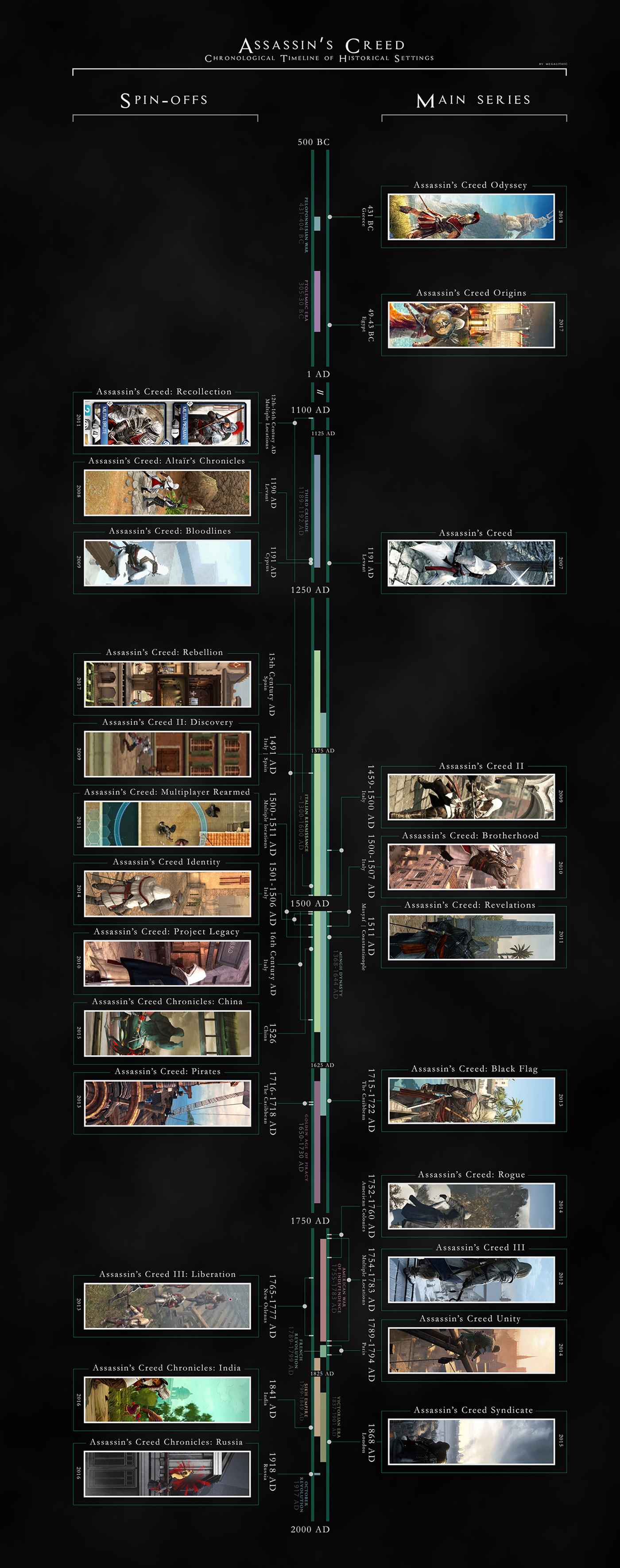

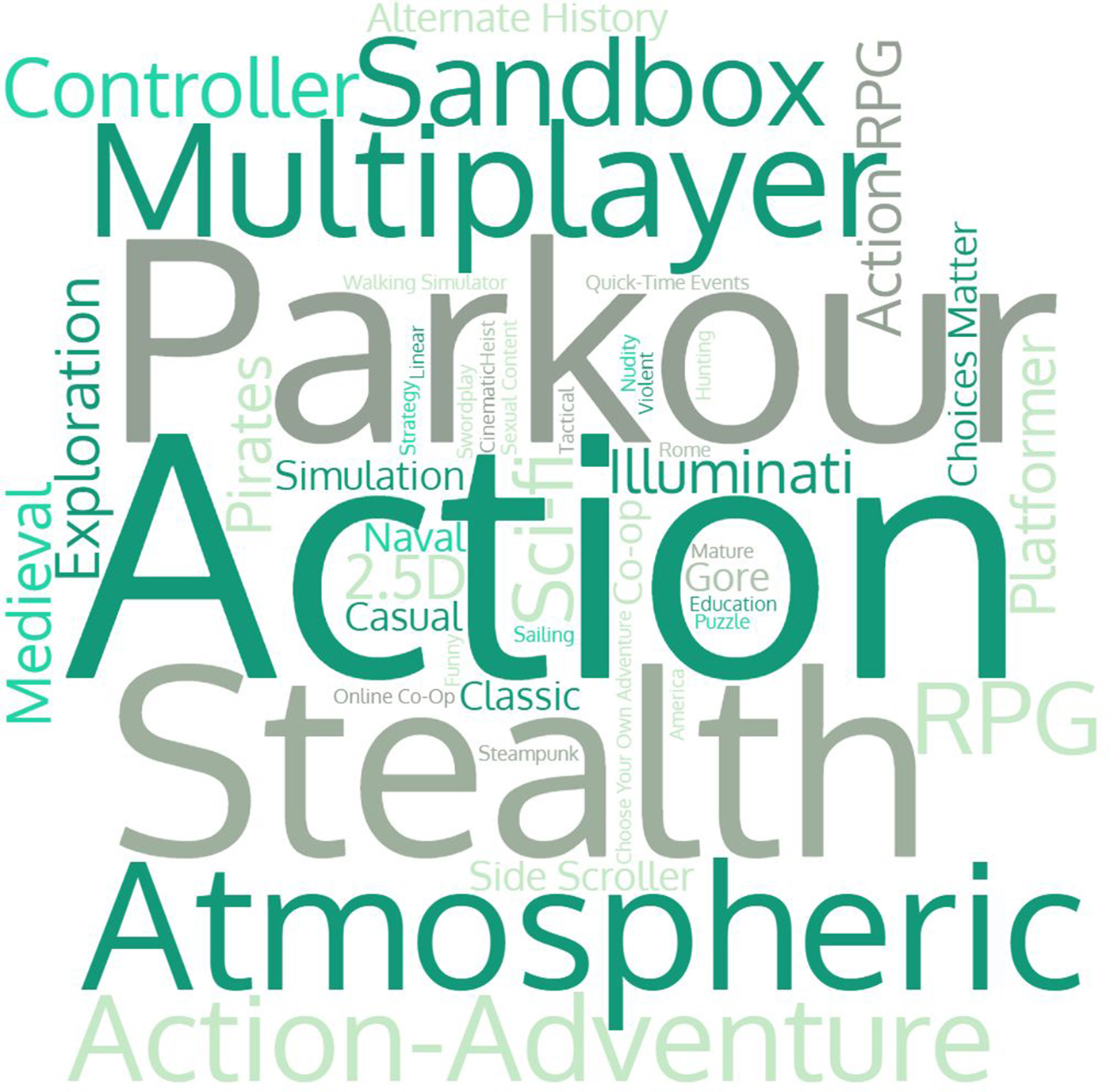

With the tagline “history is our playground,” Ubisoft's Assassin's Creed series has become the entertainment industry's highest-selling game series set in the past (Reparaz Reference Reparaz2016). Since 2007, 21 Assassin's Creed games have been released across multiple platforms, each chock full of historical places, events, and people. With almost two game releases a year, most of which explore different locations and time periods, one could be forgiven for thinking that this series is quite a chaotic collection (Figure 1). The opposite is true. The Assassin's Creed games, especially the main entries in the series (see Figure 1, top row), are quite tightly and narrowly designed. The result is a game series that revolves around a core set of mechanics and a background story that attempts to tie the different games together (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1. Timeline of all Assassin's Creed games, both main games and spin-offs, showing their date of release as well as their settings in terms of historical date, time period, and location. Image detail can be seen on the website of VALUE foundation: http://value-foundation.org/AC_Legacy_SAA.jpg. (Image by Krijn H. J. Boom, with screenshots from the individual Assassin's Creed games.)

FIGURE 2. A word cloud showing the most used tags (short words describing an aspect of the game) that the player community has used to refer to Assassin's Creed games on the popular game platform Steam. Frequency data of these tags were collected using SteamSpy's public API (SteamSpy 2019) in March 2019.

All entries in the main Assassin's Creed series can broadly be characterized as historical “action-adventure” games. The action and adventuring is all viewed from a third-person perspective (i.e., with the camera behind the main character). Players have access to three core types of activities: fighting (melee or ranged), stealth, and “parkour” (climbing, jumping, and running on, over, across, and through a built environment). Individual games have introduced new and even one-off mechanics. Some have been quite innovative. Our favorite is the ability in Assassin's Creed III: Liberation for the player to dress up either as an assassin, a rich merchant's daughter, or an enslaved person—which affects how the virtual citizens of eighteenth-century New Orleans will react to the player. Yet, as the title of the game series makes abundantly clear, the vast majority of actions a player can take ultimately revolve around one thing: assassination, or more plainly put, the act of killing other human beings.

Narrative and World

The narrative framing device of Assassin's Creed is one in which two shadowy organizations, the Templar and the Assassins—both highly mythologized versions of organizations with an already semilegendary statusFootnote 1—wage a secret war over artifacts and technologies from an advanced precursor civilization. One of the technologies used in this conflict is the Animus, a machine that allows its users to experience the past through the memories of ancestors locked in their DNA. This narrative device explains why players may visit—but are not able to meaningfully change—the past. In contrast to other historical games, such as Sid Meier's Civilization (Mol et al. Reference Mol, Politopoulos and Ariese-Vandemeulebroucke2017), Assassin's Creed never explores alternate histories. Still, a central conceit that relies on modern-day Assassins and Templars engaged in DNA-powered, ancestral piggybacking is quite frankly ridiculous. It seems to be little more than an excuse to play around in the past, which is where this series shines brightest.

The first 19 games all take place in post-classical history. Regardless of time and location, Assassin's Creed provides its players with a richly reconstructed past world: building materials and styles are period accurate, city layouts and landscapes conform to what is known about their original geography, other material culture mostly adheres to the style and technology of the day, people tend to be dressed and act appropriately, and scenes of daily life fit within scholarly expectations. Added to this general eye for detail is a penchant for historical drama: famous landmarks, events, and persons all feature prominently in the games and have often been carefully researched and precisely represented. Players can consult the in-game encyclopedia, a “database” written in the voice of a game character, to learn more about Karl Marx (Assassin's Creed: Syndicate) or the Basilica of San Lorenzo (Assassin's Creed II), for example. At the basis of these games is a clear love for the past in and of itself, which is also reflected in Ubisoft's employment of a full-time historian and frequent consultations with experts (Copplestone Reference Copplestone2017). Because of this attention to detail, Assassin's Creed can perhaps be experienced as a form of virtual heritage tourism (Champion Reference Champion2011, Reference Champion2015).

Assassinating in Antiquity

In 2017, with the release of Assassin's Creed: Origins, the series went much farther back in time, offering its first engagement with antiquity—namely, Egypt's Hellenistic period. The game takes place during the last years of the reign of Ptolemy XIII (51–47 BCE) and over a vast stretch of Egypt that includes the cities of Memphis, Thebes, Alexandria, and Cyrene, as well as the Siwa Oasis.

Along with the series’ expansion into classical antiquity, a new feature was introduced: the Discovery Tour, “a ‘virtual museum’ without threats, but instead with guided tours and historical sites to discover” (Ubisoft 2019). It allows players to visit the world of the game and explore its historical settings, and it offers information on the history and archaeology of ancient Egypt. The tour has enjoyed some critical success, although it has also been critiqued as a poorly referenced living diorama lacking interactivity (Mol Reference Mol2018; Walker Reference Walker2018). Ubisoft has stated that it has been used by schools and other educational institutions, which have employed the Discovery Tour as an introduction to the history of Egypt (Porter Reference Porter2018; Université de Montréal 2018). It is unclear what the impact of the Discovery Tour is, as user data is unavailable.

These trends continued in 2018 with the release of Assassin's Creed: Odyssey, with the designers pushing the timeline of the series more deeply into classical antiquity. The game is set in Greece during the first years of the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BCE). The main story revolves around Kassandra or Alexios (a player gets to choose whether to play as a female or a male character), who are mercenaries trying to unveil and destroy the Cult of Kosmos, a shady organization that is fueling the conflict between Athens and Sparta, while they are seeking answers about who their parents were.

The choice of the time period was a relatively easy one for the developers because it corresponds to the height of classical Greece and the so-called “Golden Age” of Athens (GameSlice 2018). This historical setting is unique among games of its kind, and it potentially offers the opportunity to experience the looming shadow of the impending war in virtual ancient Greece. As the game begins on the island of Kefalonia, it is only through rumors that the player hears about the war, until engaging firsthand with it on the Greek mainland.

The “odyssey” takes place in a semiaccurate map of Greece, mostly compressed to reduce the player's traveling time, which includes Kefalonia (the starting area) and Ithaca in the Ionian Sea, mainland Greece, Crete, and a number of islands in the Aegean. In this setting, the player has the opportunity to visit most of the ancient Greek city-states of the time, as well as some of its most storied locations, such as the Oracle of Delphi. As with Assassin's Creed: Origins, a Discovery Tour mode was also announced for Assassin's Creed: Odyssey, although at the time of writing (March 2019), this has not yet been released (Maguid Reference Maguid2018).

The developers went to great lengths to create an authentic representation of ancient Greece. Several historians and archaeologists were consulted, and the developers visited Greece to get a firsthand experience of the landscape and locations they were recreating (Dumont Reference Dumont2018). The result is one of the most detailed and beautiful installments of the series. Entering the Sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi, for instance, the player encounters all the monuments, treasuries, and stoas that would have been there in antiquity, all dressed in color, in a beautiful digital reconstruction of the site (Figure 3). The game moves away from the stereotypical representation of ancient Greece as full of white marble and ruins (Lowe Reference Lowe and Thorsen2012), and it embraces the colorful actuality of antiquity (Figures 4 and 5). Another impressive element in these reconstructions is the use of statues in relation to space. Much as it was in antiquity, the sanctuary is filled with statues, which creates an awe-inspiring visual experience and encourages the player to explore each individual element of the sanctuary.Footnote 2

FIGURE 3. The Athenian Treasury at Delphi and the street leading up to the Temple (photo by A. Politopoulos) and the same location in Assassin's Creed: Odyssey (screenshot by A. Politopoulos).

FIGURE 4. The front of the Athenian Treasury at Delphi (photo by A. Politopoulos) and the same location in Assassin's Creed: Odyssey (screenshot by A. Politopoulos).

FIGURE 5. The remains of the sixth Temple of Apollo at Delphi (320 BCE; photo by A. Politopoulos) and the same location in Assassin's Creed: Odyssey showing the classical temple (525–373 BCE; screenshot by A. Politopoulos).

A recurring theme in the Assassin's Creed series, and one which is particularly highlighted in Odyssey, is the opportunity players have to meet famous historical agents. There is the main historical figure Herodotus—the “father” of history—who acts as “guide” throughout the game, giving hints and quests to move the plot forward. It is with his counsel and knowledge that the player is able to unlock the powers that make the character stronger (e.g., acquiring new or improving existing combat abilities). Other key figures that the player interacts with include the sculptor Phidias, the politician Alkibiades, the “father” of medicine Hippocrates, and the philosopher Democritus. Classicists will already be familiar with several contextual jokes. For example, the feud between Sophokles, Euripides, and Aristophanes that unfolds during a symposium at the house of Pericles is one of the best moments in the game.

The “I was there when that happened” experience of the past offered by Assassin's Creed, in general, and in Origins and Odyssey, in particular, is one of the biggest strengths of the games. In many cases, despite historical inaccuracies, the game provides visual and virtual authenticity. An example of this is the city of Athens. Despite its compressed size and the artistic liberties taken with the layout of neighborhoods, a player feels as if he or she is exploring the actual city—particularly because of the rich and detailed reconstructed area of the Acropolis and the Agora.

At the same time, however, impressive locations such as Athens and Delphi in Odyssey stand in strong contrast to the repetitive environment and the tedious gameplay that breaks this immersion. A good example of such tediousness manifests in forts; that is, in the representation of both smaller and larger fortified settlements. Forts are nominally Athenian or Spartan, but opposing sides can only be discerned by banners and the armor of the soldiers. Regardless of location, most forts follow the same template of a surrounding wall, a couple of central wooden buildings, and a cave below. In addition, most forts have a lot of regular soldiers and a few tougher leaders to assassinate, as well as a small number of treasures to loot. As such, forts become a visually and mechanically repetitive element of the game.

In addition, interaction with historical agents is mostly limited to a few lines of dialogue, and they rarely play a crucial role in the main story (e.g., Pericles). In many ways, they exist simply to make the setting more authentic while acting as “quest hubs” for the players to do side quests. Most of their dialogue is meaningless and does not provide information about either history or the quests. As such, players will soon realize that the quickest way to play is simply to accept the quests and ignore the context, instead of engaging with the complex histories of these people.

Finally, it is noteworthy that historical figures are not targets for the player's assassinations. Player violence is visited on named but fictitious characters and, quite literally, an army of unnamed warriors. While visiting violence on unnamed combatants is hardly a new thing for video games (Jørgensen and Karlsen Reference Jørgensen and Karlsen2019), it feels jarring that no matter how few or many lives the player takes, history will not really change one way or the other. The player meets and talks to plenty of characters, and witnesses many events, but the violent story of the player as protagonist is disconnected from any historical reality.

For example, the war between the Spartan and Athenian armies, for all the impressive effect it has in the beginning, rapidly becomes a backdrop that simply “is there.” We have the opportunity to partake in battles on the side of the Athenians or the Spartans to enhance the influence of either faction on a given territory. Although these battles offer some rewards (e.g., equipment, gold), they have minimal impact on the actual game, let alone the history that unfolds in it. In fact, the only thing that changes is the color on the map as a representation of Athenian or Spartan dominance.

Consequently, a visually stunning and authentic ancient Greece is juxtaposed with repetitive gameplay and a score of empty encounters. As the game is very long, players will experience both of these aspects. The main story spans more than 40 hours of gameplay, which easily extends to more than 70 hours if one includes extras and side quests (How Long To Beat 2019). These quests force a repetition of the same types of engagements, involving either collecting materials or confronting other nonplayer characters. Both tasks are mostly resolved by violent means. Although it is easy to become engrossed in the action, in our experience, once players decide to lay aside the game for a week or two, it becomes difficult to pick it up again. Even if the historical setting is interesting in itself, the main story of the player's struggle against the Cult of Kosmos is too drawn out because it relies too much on the same type of gameplay mechanic.

Tourist or Assassin?

Whether visiting classical antiquity or nineteenth-century London, the Assassin's Creed series makes for an enticing virtual time machine. Furthermore, with the introduction of the Discovery Tour and the involvement of some of the scholarly community, Ubisoft is to be commended for doubling down on its support for the dissemination and production of knowledge about the past through its games. Based on our own experiences and judging from our discussions with period specialists (Casey Reference Casey2019; Low Reference Low2018), most Assassin's Creed games, and certainly the last two, are welcomed by scholars for presenting detailed and expertly reconstructed worlds that add to public appreciation and understanding of the pasts they portray.

There are, nevertheless, some strong qualifications to be made here. The promise that “history is our playground” is only fulfilled by these games in a limited and specific way. Even if Origins and Odyssey have shed some of the series’ “classical” action-adventure features in lieu of RPG mechanics and a more character-driven story, the only consistent way in which players get to interact with the world is through the killing of other humans. This is somewhat mitigated by the addition of the nonviolent Discovery Tour (in development, in the case of Odyssey). This tour, however, transforms the playground into a mostly noninteractive museum visit, with a very narrow range of actions available to the visitor. As is the case with most big-budget games, Assassin's Creed’s “action” is that of action movies, not the meaningful and rich set of actions available to a socially and culturally embedded agent. More sadly, the violence that players are perpetrating on virtual denizens of classical antiquity is meaningless from a diegetic standpoint: with the genetic memory-driven Animus as framing device, players can only ever be vicious interlopers on their ancestors' lives and on the histories in which they participate. Look, kill, but do not touch.

At the heart of this series’ motto and our review lies a deeper issue: Should history as it is represented in these games, in fact, be our playground? Should the Peloponnesian War—epic and exciting in Odyssey, but no doubt a ruinous, deathly conflict in actuality—be made into a playground in the first place? The same applies to other times and locales visited by the series, such as the American, French, and October Revolutions. Vis-à-vis the rampant presence of violent fun in games in general, the point of asking the question almost seems moot. Of course, this is precisely why it is even more important. Humanity has a deeply historic, complex relationship with violence—and violent play in particular—which is on full display in video games. In addition, contemporary gaming is a convoluted web of economic interests, global communities, and personal identities—as is the professional study of the past.

In short, there will be no easy solutions to the focus on violent play in historic games such as Assassin's Creed. Nevertheless, in terms of how the past is experienced in the present, it is critical to start formulating a response as a professional community. In our opinion, the only effective way to do so would be by communicating with game makers and players. In this regard, the academic collaborations sought out by Ubisoft are a hopeful sign. If such cooperation extended from gameworld into gameplay, we could perhaps come up with more diverse, or even completely alternative, ways of playing with the past. These would be equally or even more fun, and they could still take place in worlds as richly evocative as those of Assassin's Creed. There are already some good examples in the Assassin's Creed series, including the aforementioned use of dress in Assassin's Creed III: Liberation or the VIP symposium at the house of Pericles in Odyssey.

In conclusion, Origins and Odyssey can be recommended to those with an appetite for (repetitive) action-RPG games and an interest in the past, with the above qualifications. For those who do not particularly care for these types of experiences, we still recommend becoming familiar with these games—for example, through Let's Play videos or the Discovery Tours. Increasingly, games such as Assassin's Creed are the main encounters many people, including current and future students, have with the past. This is why it is important to understand that the series problematically presents its players with two faces: one of a virtual heritage tourist, mouth wide open in wonder at the beauty of the past; the other of a time-traveling murderer.