Introduction

This Element aims to analyse the transition of the Kingdom of Italy towards a democracy based on mass integration parties and the events immediately preceding its transformation into an authoritarian regime. This topic has been tackled in millions of pages, generating extensive and diverse literature. In my opinion, however, the topic has not yet reached a definitive conclusion and it is one upon which the scholarly community is far from agreement. This Element, therefore, certainly does not set out to put an end to a debate of this magnitude but intends to make a very specific contribution to it, based on just two dimensions: an electoral and, to a lesser extent, institutional analysis. The period between 1919 and 1924 marks a critical transition phase from ongoing democratisation to its collapse and the onset of an authoritarian shift. The analysis specifically focuses on the electoral cycles that initiated this transition in 1919, when the Popular Party (Partito Popolare) and the Italian Socialist Party (Partito Socialista Italiano) secured a majority in the lower house. This critical juncture represents a decisive crossroads, where the clash between different political visions led to the rise of Benito Mussolini. As will be demonstrated in the Element, an epilogue that initially was neither foreseeable by any of the actors involved nor, obviously, inevitable.

The Italian Political System in the Aftermath of the First World War

At the turn of the twentieth century, the Italian political system had been democratising, amidst ups and downs and gradually, but at a relatively steady pace. Since 1861, when the newly constituted Kingdom of Italy inherited the Statuto Albertino (Albertine Statute) as a constitution from the Kingdom of Sardinia, the spheres of participation had gradually widened to include growing numbers of citizens. One of the high points of this process was the approval of the ‘almost’ universal suffrage in 1912 for elections to the Chamber of Deputies, the only elective chamber. The 1913 elections that followed had produced a transformation that was still largely silent and not fully perceived by most. As Alessandro Schiavi (Reference Schiavi1914) reported, however, the dichotomy then ceased to be between liberal, conservative, and progressive forces but between liberal forces and Socialists, at that time the only party with a mass, national structure. The events of 1915 that led to the country’s entry into the First World War, on the other hand, showed how its democratic foundations were still fragile and how, from within the country, a new social class was emerging that opposed the Socialists and parliamentarism and reverted to hyper-nationalist logic. With Italy not yet involved in the First World War, after the street demonstrations of the ‘Radiant Days of May’, the Chamber of Deputies, with a neutral majority, was therefore forced to accept a fait accompli and approve the state of war, something that took place on the basis of a double pressure: on the one hand, that of the movement that aggregated various very violent interventionist forces – nationalists, D’Annunzians, and Mussolinians – and, on the other, the Crown itself and the conservative liberals who were at the head of the government. Once the war was over, a long phase of institutional fluidity opened in Italy and Europe. In a sign of great instability and the search for a new order, five electoral cycles followed one after the other, from 1919 to 1924: the legislative elections of 1919, 1921 and 1924 and the administrative elections of 1920 and 1922–3. This transition initially seemed to lead to a completion of the democratisation process and only later ended with the consolidation of an authoritarian regime. In this Element we shall focus on this period, in order to understand the electoral and institutional dynamics that allowed the transition from the first to the second part. And, to do so, we shall focus, above all, on the relationship within an imaginary triangle formed by representation, the parties, and elections. Within this triangle, the focus will be on analysing the cleavage opposing liberal formations to mass integration parties and, even more specifically, on the attempts to construct a conservative party capable of integrating the middle classes within democratic institutions. This process was particularly significant because it was a response to the evolution of the Socialist Party, which had already completed its process of affirmation and integration of the proletarian classes, both urban and agricultural.

It was necessary to adopt a multilevel approach in order to understand the deeper reasons for this long process of transformation. The First World War and its consequences on society were certainly among the causes that accelerated a process that was already underway, but behind them laid implicit dynamics, associated with the transformations that preceded the war, and explicit ones: that is, referable to the political system, such as the suffrage reform approved in 1912. The first level lay in the paradox of a democratisation process that would remain partial and unfinished and that, in fact, would never touch the Albertine Statute granted in 1848. Akin to what happened in other European countries after the First World War, a broad debate developed in Italian public opinion, in the parties and among constitutionals, which focused, above all, on the need for reform of the Senate, the upper chamber that, although not elective, retained numerous powers to intervene in the legislative process. In addition, the discussion addressed the issue of the multiple powers that the king still exclusively enjoyed, particularly in the field of foreign policy. The convocation of a constituent assembly, which could have overturned the relationship between the Crown and the representative institutions, was then also hypothesised. Whereas under the statute these were still in some way legitimised by the king by their very existence, with the constituent assembly it would be the king who would be legitimised by them, as had happened for example in Belgium, where the sovereign had been chosen by the assembly after the approval of the constitution in 1831. A paradigm shift that was not easy to accept in the House of Savoy because, although the action in the political system of the heads of state had often been silent, it was far from irrelevant (Colombo, Reference Colombo2010: 10–15). In this context, the elections of 1919 represented the greatest upheaval in Italian politics since the beginning of the liberal age. The mass parties then became a majority in the Chamber of Deputies, while the upper chamber maintained a majority of ‘Constitutionals’. The shock brought about a substantial freezing of the debate on the reformability of the political system and an accentuation of a desire for crystallisation that would preserve it from complete disruption.

The second level was the crisis of all the political formations and the upheaval of previous balances. In the conservative camp, there was a real crisis and the inability of the right-wing leadership to adapt to the new rules imposed by the enlargement of suffrage. This made it difficult for part of the country to identify with the democratic state. The inability to constitute a viable party proposal in this field was undoubtedly partially due to the fact that a large section of the liberal world would have preferred a return to a model in which the government was not dependent on the confidence of parliament, instead returning completely to the sphere of the king; that is, they wanted a ‘return to the Statute’ – a more rigid interpretation of the constitutional charter. Added to this was a second dimension that upset the balance of the political system, namely the birth of a Catholic party. In 1913, in the first elections with universal male suffrage, the Catholic vote had united to support the candidates of the liberal formations. In 1919, on the other hand, Catholics stood as candidates with their own party, the Popular Party, which obtained 20 per cent of the seats in the lower house, inevitably causing a haemorrhage of votes, especially in the north, for the Constitutionals. However, the party that soon showed an intrinsic weakness, due to the contrast between different currents, some more intransigent and others more attentive to collaboration with the conservatives, and the fluctuating relations with the Vatican. Finally, there was always the seemingly unstoppable development of the socialist movement and the workers’ movement: socialists who were also internally far from united and who would soon go through the split from the left of the future Communist Party and the marginalisation of the reformists.

Some Methodological Notes

Before proceeding, it seems useful to clarify some relevant methodological notes. Firstly, it is necessary to define the typology of the parties involved, aiming to reduce complexity, number, and diversity, even if at the cost of some precision. They will be grouped into two broad areas, liberal parties and mass integration parties. Liberal formations – or formations of cadres or notables – will be defined as all those formations with little or no formalised organisational structure, not dependent on a membership base, generally composed of social, economic, and intellectual elites and with that privileged negotiation between elites. Here, given the impossibility of reconstructing the extremely chaotic and volatile field of liberal parties (Democratic, Liberal, Constitutional, etc.), they will be grouped together in a dimension that, following a cataloguing model proposed by the Ministero dell’economia (1924a: 55), joins all these formations under the single definition of Costituzionali (Constitutional parties). On the other side of the spectrum, there were the mass integration parties. For the sake of simplicity of analysis, here we will define a mass integration party on the basis of three dimensions. The first is the organisational structure, that is, they have an organisation rooted in the territory based on militancy. The second is the mobilisation strategy: that is, they aim to mobilise broad sectors of society, often around ideologies or collective identities. The third is the relationship with voters. That is, they seek to create direct and lasting ties with their voters, often through the offer of material and symbolic benefits and through building ‘party loyalty’ among their members and supporters (Duverger, Reference Duverger1954: 63–78).

The second methodological note concerns the data considered and processed. Electoral statistics, an impressive mass of numbers, allow us to understand in depth the political balances and imbalances in their evolution. It was decided as a starting point to recount all the candidates and all those elected in all the electoral rounds considered, starting from the tables compiled at the time by the official bodies and not referring to secondary sources. Unfortunately, reading them is not always easy: the geography of the constituencies changed from election to election and so it was necessary, in order to favour comparability, to reduce their complexity. An attempt was therefore made to convert the constituency map to a single geographical scheme, summarised not on the province but on the region, or in some cases on an amalgamation of regions. The analysis of the electoral data was done by emphasising four cleavages that seemed the most effective for understanding the critical juncture: north/south, abstention/participation, local/legislative elections, and mass/constitutional parties. A separate discourse will be made for the selection of candidates for the 1924 Fascist List and elections. In this case, it was necessary to focus more on the precise reconstruction of the biographical data of each of the individual candidates in order to bring out the relationship and transition between the old elites and the new elites.

Finally, we chose to focus on a rereading, also from the primary sources, of the main newspapers of the time. Many newspapers were consulted, but we chose to favour the detailed analysis of the liberal-leaning Corriere della Sera, the Italian newspaper with the largest circulation of the time. Its pages are essential to understand the climate and to grasp the point of view of those who considered themselves on the side of the ruling class and how the transition process to a democracy based on mass parties was experienced.

Inevitably, there was not space in this Element even for many relevant things. We wanted to focus almost exclusively on the electoral processes. Thus, it was impossible – and probably would not have been consistent with the specific approach chosen for this study – to delve into the events linked to the Biennio Rosso (1919–20) or Gabriele D’Annunzio’s adventure in Fiume (1919–20). This is not so much because their importance and destabilising effects are not understood but because an attempt will be made here to identify the weaknesses of the Italian political system, even in what appears less visible. Thus, the events surrounding the March on Rome are only dealt with in terms of the negotiations for the formation of a new government between 27 and 30 October. We will not dwell too much on the violence of squadrism, except when it has a direct impact on institutions, such as when the assault on the municipal chambers led to their dissolution. These are all issues that have been abundantly addressed and resolved elsewhere.

1 The November 1919 Elections

The Popular Party

The 1913 elections had not ended in catastrophe for the parties of the liberal sphere only because the Catholics, not yet organised into their own autonomous party, had supported anti-socialist candidates on the basis of a specific programme. In 1919, however, Catholics entered the political arena themselves, organising themselves into a nationwide structured party, the Popular Party, founded on 18 January 1919 by the parish priest Don Luigi Sturzo, with the appeal ‘To all free and strong men’. It was a party that was already born with a number of peculiarities. First of all, it was born out of the coming together of many and very different Catholic organisations. Then, since its birth, it had formed itself an organisation similar to that of the Socialist Party which, since 1892, the year of its foundation, had branched out into a dense network of parallel structures, such as trade unions and cooperatives. The birth of the Popular Party also called into question the clear separation of Church and State and Pope Benedict XV’s revocation in 1919 of the Non expedit, or Vatican ban on Catholics taking part in national votes, a separation that had been maintained since the taking of Rome in 1870, when Italian troops put an end to the existence of the Church State. The party, therefore, was not born out of nothing: it could already count, at its inception, on the Catholics’ mature experience in parliament and government. They had managed to gather nineteen deputies in the group, and by the time of the Bologna Congress in the summer it had grown to thirty-one.

For our analysis, it is important to emphasise the effect that the birth of the Popular Party had on both the party system and the political system. On the face of it, the Popular Party was a force that at times appeared parallel and specular to the Socialist Party, sharing in part its structure and its corporatist/democratic afflatus: that is, the desire to overcome the capitalist economy (De Rosa, Reference De Rosa1972: 24), and the demand for the transformation of the Senate. They shared, in other words, everything that Italian liberalism had always tried to avoid. In the Popular Party programme, there were three points that concerned a broad transformation of representation: the electoral law, which was to provide for proportional counting and also the proposal to grant women the right to vote; the administrative decentralisation of municipalities, provinces, and regions; and the electivity of the Senate, with the introduction of corporatist principles (Cantono, Reference Cantono1920).

After the challenge of the Socialist Party which, in 1913, had already obtained almost 20 per cent of the votes at a national level, concentrated mainly in the north of the country, the liberal world was now also challenged in its waning hegemony by the entry on the scene of another mass integration party that was competing for the favour of contiguous sections of the electorate. In 1913, in a system made up of uninominal constituencies, the liberals, thanks to the Gentiloni agreement, had been able to save themselves thanks to the Catholic votes, that support was now lacking (Adinolfi, Reference Adinolfi2024: 36). Sturzo, moreover, had not looked favourably on that agreement and believed, on the contrary, that the involvement of Catholics should be carried out in the first place with an autonomous force. Even the new Pope Benedict XV had shown himself benevolent towards Sturzo’s initiative and, although he never openly expressed his support, this did not seem to be enough to limit the dissension in the Catholic world and within the newly formed party. The currents that formed within it immediately undermined the party in depth and, as we shall see, played a crucial role in all the salient moments of the following years. It was thus configured as a party divided between an intransigent current, headed by its leader, and a ‘collaborationist’ one, closer to the more conservative fringes of the country. The centrifugal force exerted by these two currents, even in the face of a Holy See that was more inclined to support the collaborationist strategy, played a decisive role in causing the Catholic party project to collapse. Already in 1919, when Sturzo found himself having to construct lists for the elections, he felt obliged to take into consideration all the various souls of the party, from the clerical moderates to the nationalist Catholics. One of the first clashes came as early as 1920 over the formation of lists in the local elections, characterised by a majority law that had led to the aggregation of a poll whose only glue was anti-socialism (De Rosa, Reference De Rosa1972: 97). Therefore, the Popular Party suffered from being both a governmental force and a sort of anti-system party at the same time and was hindered by these divergences in its project to take a central role in the political scenario in a country that had always been profoundly anti-clerical.

Towards a Conservative Mass Party

At the appointment with modernity the conservatives presented themselves without adequate answers. This is a fundamental aspect of Italy in 1919: on the right of the political quadrant there was a lack of credible proposals for the electorate, and this fragility would play a fundamental role in the following years. The question of creating a conservative party had, in fact, been dragging on for decades, without an effective solution ever having been found.Footnote 1 Since the 1911 war against the Ottoman Empire to gain control over Libya, nationalist ideals had enjoyed some success among students and the middle classes (Nardi and Gentili, Reference Nardi and Gentili2009), and the idea of forming a Fascio Liberale,Footnote 2 a bloc to unify the conservative and liberal forces, began to make headway. The government crisis that followed the defeat at Caporetto in 1917 led to the presidency of the council by Vittorio Emanuele Orlando and the formation of a new group in the chamber that took the name of the Fascio Parlamentare di Difesa Nazionale (Parliamentary Fascio of National Defence). Initially, the Parliamentary Fascio was not intended as a party, but as an aggregation of parliamentarians of multiple political sensitivities with the sole purpose of supporting the new government in the context of the war. However, some MPs soon decided to give the new formation a permanent character, seeking to give it both a ramified organisation and a unitary statute binding on all members. The group, which met at a conference in Milan in early 1918, already counted on 158 deputies and 122 senators in May. The mass integration model aimed to bring together not only individual militants but also associations that could gravitate around the future party.

Yet, despite the conventions, conferences, and proclamations, the whole project struggled to take off as a structured party. On 25 May at the Argentina theatre in Rome, the Parliamentary Fascio, meeting with 300 associations, decided to give itself a unitary and federative structure.Footnote 3 On 20 November, it was Antonio Salandra who emphasised the importance of the new formation, given that ‘great bold reforms were needed and it was necessary above all that the nation’s supreme representatives could no longer be manipulated in an old church’ and that ‘the Fascios needed to survive the war’. On 21 January 1919, a more detailed programme came out calling for the vote for women and the demand for reform of the Senate. The experience of the Parliamentary Fascio, however, was soon shattered, overwhelmed by the very logic of that old world to which many of its adherents belonged: that of a policy based on old patterns and dialectics anchored to liberal dynamics, which saw the electoral constituency as a sort of possession of the deputy himself and, as such, not subject to party dynamics. The ultimate crisis began when the Fascio decided, on 14 July, to vote against the Nitti government:Footnote 4 a wrong that was never forgiven.

Despite its short duration, the significance of the Fascio’s experience was remarkable both for the Italian political system as a whole and for the history of the organisation of liberalism. A significance rooted first of all in its numerical size and in the fact that the organisation was able to embrace both the chamber and the Senate and, further still, in the discipline required and the subordination of individual parliamentarians. And, finally, in how, once the war was over, it was able to exercise a degree of control over the Orlando government that would have been hardly conceivable in the pre-war parliamentary context (Ulrich, Reference Ullrich, Grassi, Quagliariello and Orsina1996: 497). With its failure, the possibility of rebalancing the Italian party system, orphaned of a conservative right wing capable of aggregating an important part of society, was also definitively closed, making available, to those capable of occupying it, all the political space left unoccupied by the contraction of the Liberals.

Senate Reform

The transformations of the political system had never touched the Albertine Statute: the major reforms of those years had only concerned suffrage and electoral law. The practice, however, had changed considerably: generally, the executive depended on the confidence of parliament. However, it should not be forgotten that the House of Savoy, at crucial moments, could and did use its powers, as had happened in 1915 with the First World War (Colombo, Reference Colombo2010). To these de facto transformations, a series of profound transformations in the party system, as seen so far, had been added, generating an anomalous situation in the functioning of parliament. Until 1913, the majorities in the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies were largely consistent, not least because senators were appointed in large groups. This was due to ‘waves of appointments’ proposed by the government and accepted by the king. The Senate’s approval of what had already been discussed in the chamber was not at all taken for granted, and it also had a conditioning effect. The measures were generally negotiated between the two branches of parliament. In a mass integration-party system that emerged from the 1919 elections, however, this mechanism generated different majorities in the two branches of parliament that blocked the political decision-making process. The elections had highlighted a major contradiction that had hitherto mattered little: the problem of the non-electivity of the Senate.

After all, even at a European level, the transformations taking place were profound, and all went in the direction of greater democratisation. The problem of the ‘constituent assembly’, that is, of an elective chamber with the task of drawing up a new fundamental charter, was firmly in the background of the debate at the time as the reform of the Senate. An article by Senator Tommaso Tittoni (Reference Tittoni1918), published in the pages of Nuova Antologia, offers insight into some of the proposed reforms that were being considered at the time: a Senate term of nine or twelve years with partial renewal to ensure continuity of the office; reduction of the royal appointment to a limited number of senators, creating an electoral college made up of universities and high culture associations; and second-tier regional election. Outside the Senate, the ideas in this regard were obviously much more radical. As early as February 1919, Claudio Treves, a socialist deputy from the reformist faction, advocated for the need for a constitutional assembly to review the entire institutional framework and to abolish a Senate that was ‘the powerful reserve army for supporting the will of the king and the ruling political class against the will of the people’.Footnote 5 The Popular Party also recognised that the state’s crisis was a crisis of its institutional form, and that this crisis concerned, above all, the lifelong assembly (Lanciotti, Reference Lanciotti1993: 300). However, the Catholics’ idea was to establish an elective Senate as a direct representation of national, academic, administrative, and trade union bodies, offering an alternative model to both the socialist and liberal models. The former was based on the idea of class, and the latter was based on individualism. The popular model, on the other hand, provided for a strong organic inspiration (Antonietti, Reference Antonetti1985: 260).

The senators tried to survive in what was becoming a hostile environment for them. They discussed a reform that, in reality, failed to inspire enthusiasm among both the advocates of popular sovereignty and those of a political body that, in the liberal tradition, was supposed to defend the institutions from the very idea of that sovereignty. To study how to introduce elective elements into the upper chamber, a twenty-five-member commission was established. One of its proposals was to create a specific electoral constituency for the Senate, characterised by an electoral body distinct from that of the House. In August, the Senate reform bill was submitted to the offices. The bill proposed that the upper chamber would consist of 60 members appointed for life by the king, 60 elected by the Senate, 60 elected by the Chamber of Deputies, and 180 elected by constituencies. The commission largely favoured the introduction of an elective element, with only a minority opposing it, seeking instead to significantly limit the scope of this reform. The majority report justified the reform with the need to establish criteria of popular sovereignty to the second branch of parliament, a representation that had to be of both voters and interests. In this sense, therefore, the new Senate was to incorporate the principles of representation and, at the same time, counterbalance the Chamber of Deputies, which, with universal suffrage, became a chamber representing the interests of the majority classes of society, that is, the lower classes. Hence the need for its reform in order to remedy this paradox.

Changing the direction of these debates came with the November 1919 elections and the affirmation in the Chamber of Deputies of the Socialist Party – with 156 deputies – and the Popular Party with 100 (256 out of 508). The political climate altered abruptly and the Senate became the bastion of defence for the liberal political class.

Electoral Law Reform

In April 1918, the government had extended the parliament elected in 1913 by one year and, after a series of relatively complex steps between the chamber and Senate, on 16 December 1918, the right to vote was extended to all male citizens aged twenty-one and older (Ballini, Reference Ballini2011: 4). In March 1919, socialist leader Filippo Turati proposed a proportional electoral reform to the chamber. The underlying idea of the reform project was to channel anti-system or opposition forces within the institutions (Ballini, Reference Ballini2011: 6). The proposal for the new law was accepted, but not with the broad agreement that had characterised the approval of the ‘almost’ universal suffrage in 1912. At the time, Giuseppe Micheli, a Catholic member of parliament, clarified that the proposed electoral law wouldn’t merely entail transitioning from a single-member constituency system to a proportional one; rather, it would signify a shift towards acknowledging the party-based system of representation. In short, the concept of mass party representation was to ‘overcome the inorganic and apolitical atomism of electoral localism’ (Ballini, Reference Ballini2011: 10). In the end, the proportional reform aggregated 240 votes in favour and 63 against, thus becoming Law No. 1401 of 9 August 1919. Consequently, the constituencies were redefined in September. The 508 deputies of the new parliament were to be elected in 54 constituencies, consisting of one or more provinces. Moreover, there was no reward for political forces that were organised at a national level to reduce fragmentation. In this way, forces that had a strong local base in the constituency were favoured.

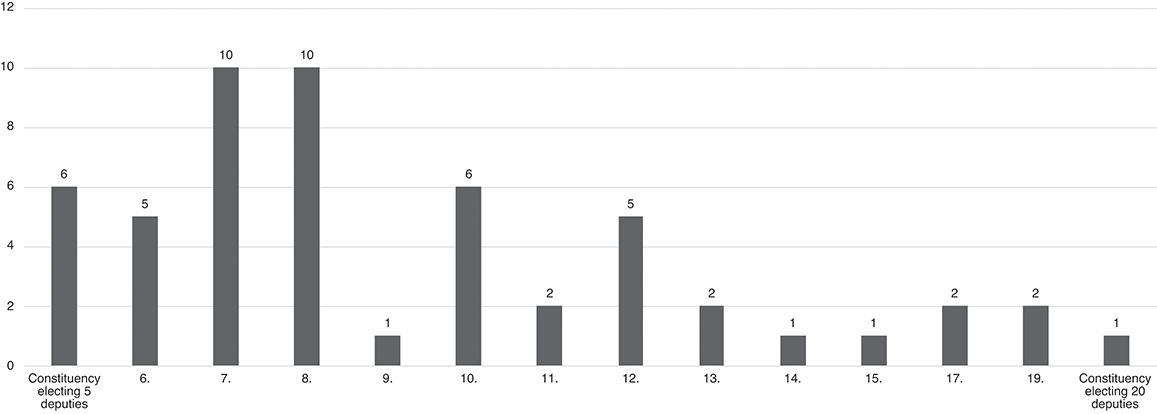

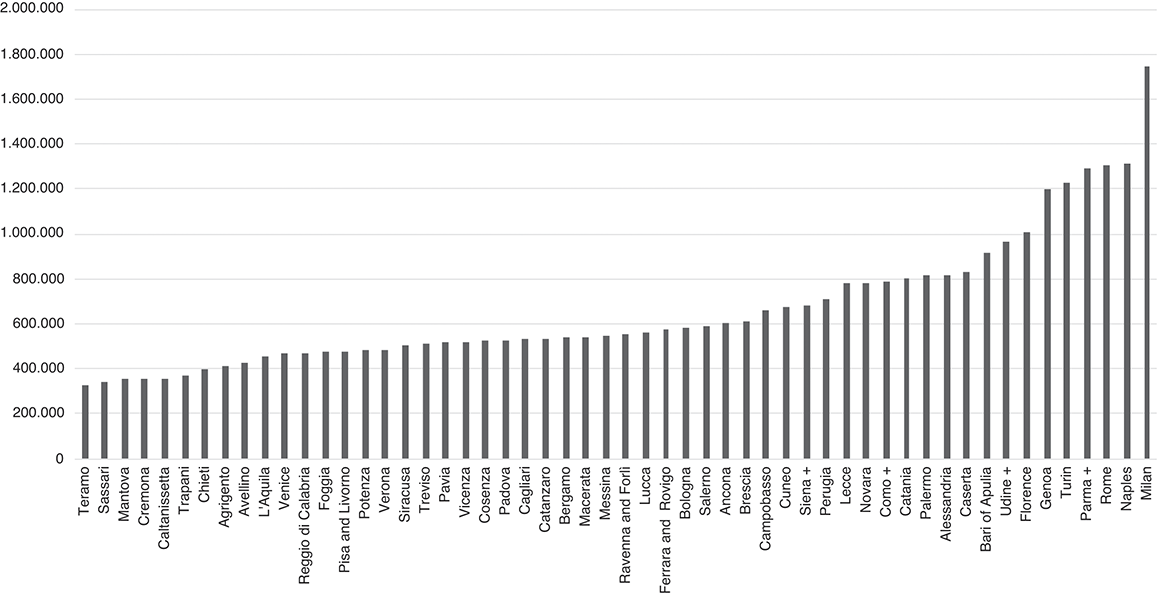

The number of deputies to be elected in each constituency varied from 5 to 20 (Figure 1) and the size of the constituencies ranged from 355,868 inhabitants in Caltanissetta to almost 2 million in Milan (Figure 2) (Ministero per l’Industria, 1920: 20).

Figure 1 Number of deputies elected in each constituency.

Figure 2 Number of inhabitants in each of the constituencies.

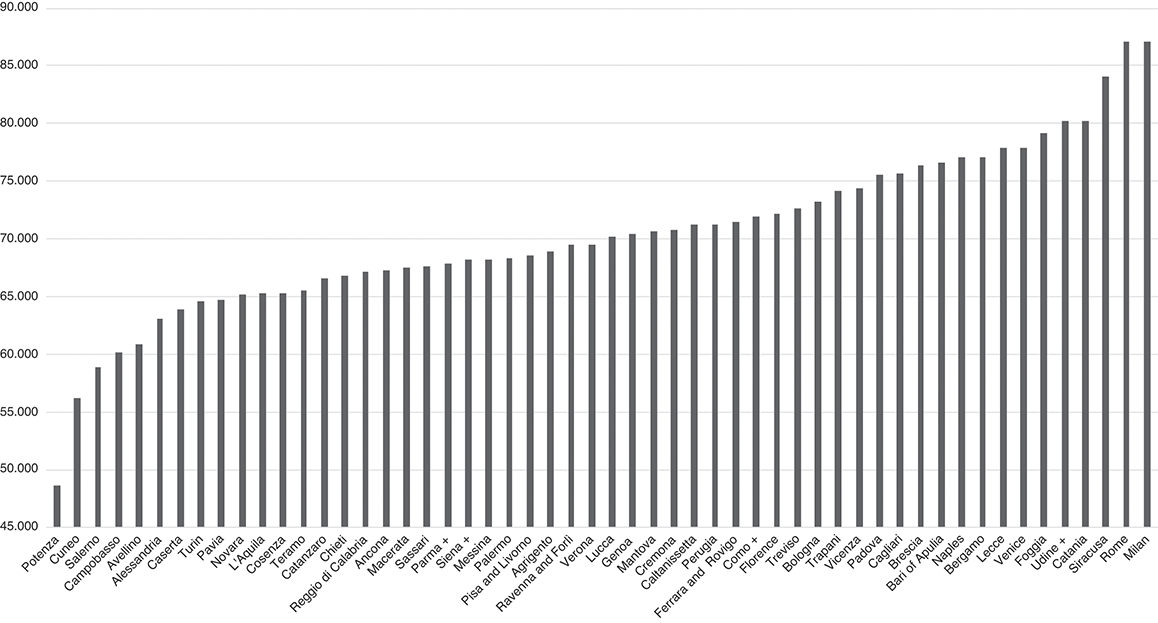

The average number of votes needed to elect a deputy thus varied considerably from constituency to constituency: in Potenza, 47,969 voters were sufficient; in Rome almost 100,000.

As shown in Figure 3, it was an extremely diverse electoral geography, which generally favoured proportionality. Few deputies were elected in small districts, which, given the D’Hondt method, tended to favour larger parties.

Figure 3 Electors needed to elect a deputy.

The Socialist Party between Social Democracy and Communism

The events occurring within the Italian Socialist Party at that time reflected the challenges, trends, and uncertainties of the European left. First of all, it must be specified that when we refer to socialists we must think of a complex universe, made up of multiple organisations that coexisted and were intertwined with each other. There was the trade union of the Confederazione Generale del Lavoro (General Confederation of Labour – CGdL), there were the cooperatives, the taverns, the party, and the Case del Popolo (People’s Houses). Then there were the municipal administrations, with which, through the municipalities, public services were implemented; from welfare, such as kindergartens, to the electrification and development of public transport. The socialists had given life to a project that was as much political as existential and which was constituted, through its network, by a totalising experience, transversal to the public and private spheres of the people who militated in it. The party had developed mainly in Emilia, Tuscany, Veneto, Lombardy, and Piedmont, but had not managed to cross the borders of the south. Among the larger European socialist parties, it had also been the only one to maintain a neutralist position throughout the First World War and had paid the price with the arrest of many of its leaders, including its own Secretary Costantino Lazzari and Giacinto Menotti Serrati. Despite the electoral weight and the fact that they had played a fundamental role in democratisation processes, the socialists had never held government roles except at the level of municipal administrations. Finally, it had been thanks to a sort of alliance between the Liberal leader Giovanni Giolitti and Turati that, in 1912, the reform that led to ‘almost’ universal male suffrage had been approved. But, in the post-war period, these informal collaborations were no longer tenable, and positions had become decidedly polarised.

It was inevitable then that, in a framework where the conflict had not lived up to the promises made on the eve of the conflict, the legitimacy of the socialists was very high. A further inevitability was that, after the Soviet Revolution and with the terrible economic conditions that followed the war, tensions within the party would grow and pressure from below, which had manifested itself in the spontaneous bread riots in Turin in August 1917, would increase (Arfé, Reference Arfé1975: 251). At the XVI Congress in Bologna in October 1919, the party decided to join the Third International, or Communist International, by acclamation – a choice that had also arisen as a consequence of the collapse of the Socialist International that had preceded the world conflict through the Brussels International Bureau. The relationship with Moscow, with all its contradictions, would then characterise the entire life of the socialists in the post-war period. In contrast to other European experiences, the Italian Socialist Party housed both revolutionary and reformist factions, with the revolutionary faction itself divided into communists and socialist maximalists. In 1919, most of the revolutionary movements outside Russia had been quashed. Despite the persistence of revolutionary rhetoric, few were truly convinced that the Bolshevik revolution was imminent. Theoretically, there was a proposal to replicate what was done in Russia. Still, in practice, it became evident that such a course of action was unfeasible. It was evident to most that the state was, in any case, stronger and much better organised in the field of repression. Membership of the International implied the acceptance of a number of rules, including that of expelling the reformist fraction. On this point, the party wavered, and the breakaway of the Reformists only came in October 1922, in a climate already deeply marked by fascist violence and just days before what was to be the March on Rome. Until then, however, some form of coexistence between the two factions of the party, albeit with increasing conflict, was always found, and the split came not from the reformist side but from the communist faction at the Livorno Congress in January 1921. In the aftermath of the 1919 Congress, however, it was still possible to celebrate the unity of the party and start campaigning for elections.Footnote 6

The 1919 Elections: The Electoral Earthquake

On the eve of the 1919 election, predictions made by the Corriere della Sera seemed to reassure liberal circles of the turnout results. The general forecasts gave the Socialists between 90 and 100 seats – a third of which to the maximalists – and the Popular Party between 65 and 75. The Costituzionali would, therefore, be left with 350 of the 508 seats, a more than sufficient portion to be able to govern. Thus, it was predicted that 30 per cent of seats would go to the mass parties and the rest to a plethora of undefined, divided formations, unable to build stable majorities.Footnote 7 Before proceeding to an analysis of the results of 1919, it must also be remembered that, in the 1913 elections, the Socialists had taken almost a million votes, about 17 per cent, but, penalised by the single-member electoral system, only fifty-two deputies.

Taking a very first look at the structure of the results coming in from the polling stations (Table 1), there were just over 10 million registered voters, from which, however, had to be subtracted the emigrants, some 500,000, and the soldiers who were not entitled to vote; almost 1 million.Footnote 8 Participation was low: about 60 per cent of the eligible voters had voted, less than in 1913. The turnout was very high in Emilia (71 per cent), followed by Lombardy, Piedmont, and Tuscany. In contrast, the turnout was very low in Sicily (50 per cent), Campania, and Marche. In general, more people voted in the northern regions than in the south. There was also very high fragmentation. On average, ten lists were presented for each constituency. The highest number was in Campania, with twenty-one lists, and Sicily with fourteen. Lazio and Umbria and Marche, on the other hand, had six and five lists. Only two lists were present in almost all the constituencies: the Socialist and Popular lists. The re-election rate of the deputies who were already in the chamber in 1913 was very low: in 1919, 65 per cent of those elected became deputies for the first time; by far the highest figure ever. This proportion had, in fact, been 32 per cent in 1913 and even 21.3 per cent in 1900. Only the southern regions had slightly lower percentages of newly elected representatives, but they were still over 50 per cent (the only exceptions being Abruzzi and Molise, where it was 45 per cent) – an anomalous figure that broke all averages and gives us a first indication of what was happening.

Table 1 Results of the 1919 Italian parliamentary elections

| Regions | Average Voters | N. Lists | Electorate | Emigrants | Soldiers | Voters | Valid Votes | Socialists | Popular Party | Costituzionali | Other | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N. | % | N. | % | N. | % | N. | % | ||||||||

| Piedmont | 66.0% | 11 | 1,130,418 | 43,430 | 79,324 | 665,388 | 646,396 | 326,574 | 50.5% | 122,927 | 19.0% | 196,895 | 30.5% | ||

| Liguria | 61.2% | 8 | 403,575 | 8,966 | 49,105 | 211,428 | 211,428 | 66,529 | 31.5% | 42,913 | 20.3% | 101,986 | 48.2% | ||

| Lombardy | 67.3% | 11 | 1,484,105 | 22,745 | 140,942 | 889,178 | 889,178 | 409,389 | 46.0% | 268,473 | 30.2% | 211,316 | 23.8% | ||

| Veneto | 57.6% | 10 | 1,121,219 | 26,107 | 112,204 | 566,432 | 555,032 | 207,642 | 37.4% | 186,653 | 33.6% | 150,243 | 27.1% | 10,495 | 1.9% |

| New Provinces | |||||||||||||||

| Emilia | 70.8% | 8 | 811,912 | 11,738 | 103,813 | 492,688 | 490,693 | 288,194 | 58.7% | 92,643 | 18.9% | 83,093 | 16.9% | 26,764 | 5.4% |

| Tuscany | 62.5% | 10 | 895,186 | 23,355 | 109,907 | 476,289 | 473,543 | 207,791 | 43.9% | 94,298 | 19.9% | 156,333 | 33.0% | 15,121 | 3.2% |

| Marche | 50.7% | 5 | 367,619 | 24,612 | 33,704 | 156,879 | 154,976 | 52,143 | 33.6% | 42,380 | 27.3% | 48,205 | 31.1% | 12,248 | 7.8% |

| Lazio and Umbria | 54.6% | 6 | 632,301 | 42,673 | 40,137 | 300,112 | 295,506 | 99,358 | 33.6% | 66,323 | 22.4% | 108,745 | 36.8% | 21,080 | 7.0% |

| Abruzzo and Molise | 57.7% | 11 | 582,882 | 80,628 | 27,002 | 274,249 | 277,492 | 28,729 | 10.4% | 20,044 | 7.2% | 228,719 | 82.4% | ||

| Campania | 51.1% | 21 | 962,445 | 48,607 | 37,943 | 447,371 | 444,500 | 26,586 | 6.0% | 81,995 | 18.4% | 305,984 | 68.8% | 29,935 | 6.7% |

| Apulia | 55.4% | 9 | 648,483 | 23,153 | 43,844 | 322,155 | 322,173 | 59,015 | 18.3% | 33,758 | 10.5% | 229,260 | 71.2% | 140 | 0.0% |

| Calabria and Basilicata | 55.9% | 12 | 622,773 | 82,169 | 25,103 | 288,216 | 286,920 | 19,196 | 6.7% | 37,317 | 13.0% | 228,653 | 79.7% | 1,754 | 0.6% |

| Sicily | 49.8% | 14 | 1,165,775 | 83,934 | 65,817 | 505,919 | 498,812 | 32,682 | 6.6% | 62,075 | 12.4% | 398,544 | 79.9% | 5,511 | 1.1% |

| Sardinia | 56.0% | 9 | 244,421 | 4,607 | 11,197 | 127,957 | 127,588 | 10,964 | 8.6% | 15,556 | 12.2% | 101,068 | 79.2% | ||

| Total | 59.2% | 10 | 11,073,114 | 526,724 | 880,041 | 5,724,261 | 5,674,237 | 1,834,792 | 32.3% | 1,167,354 | 20.6% | 2,302,818 | 40.6% | 369,273 | 6.5% |

On 18 November 1919, La Stampa, the liberal daily newspaper based in Turin, commented on the election results with a full-page headline: ‘The resounding condemnation of the war in the suffrage of the people. The enormous socialist dominance and the affirmation of the Popular Party’. In essence, the electorate’s condemnation of what had been an unwanted intervention that had generated immense drama was unequivocal.Footnote 9

Indeed, the Socialists, the most determined anti-war political force, were by far the most voted-for party, with almost two million votes and 32 per cent of the future parliament, followed by the Popular Party with just over one million votes (20 per cent). The mass parties obtained more than half of the votes, with 156 and 100 seats respectively (Table 2), that is, an absolute majority of the 508 deputies in the chamber. The Fascio Parlamentare elected only two deputies, Paolo Boselli and Giuseppe Bevione, but it must be said that it did not even present itself with its own list, but rather joined those of the Monarchist Liberal Party (Baravelli, Reference Baravelli and Schinnà2021: 278). The figures, of course, varied from region to region. For instance, the Socialists failed to secure any Calabria, Basilicata, Sicily, and Sardinia deputies. However, they constituted the majority in Piedmont. Moreover, in Emilia, they boasted a significant representation of 67 per cent of the deputies. The Popular Party was also decidedly stronger in the north, where it had 31 per cent in Lombardy and 37 per cent in Veneto, while in the south, it only obtained percentages between 10 and 20 per cent in all constituencies (Table 2). In other words, the mass integration parties established their influence across all economically advanced regions characterised by rapidly changing social structures. The results of the Constitutional parties were specular to the Socialist and Popular: they were in the minority everywhere in the north (around 20 per cent), while in the south, from Abruzzo downwards, they were everywhere above 80 per cent. Italy still remained a strongly divided country, with polarised political, economic, cultural, and social structures clearly visible in the election results. The defeat of the Fasci di Combattimento, Mussolini’s party, was also harsh: its results clearly showed that it was still extremely fragile and that, as Renzo De Felice points out, the figure of 40,000 members propagated in the election campaign had been greatly inflated (De Felice, Reference De Felice1965: 568). They also lacked a precise strategy of alliances because, on the one hand, Mussolini imagined making blocs with left-wing interventionism; on the other hand, Michele Bianchi was more inclined to settle on a case-by-case basis (De Felice, Reference De Felice1965: 569). In this scenario, the conflict between the mass integration parties and the liberal parties became increasingly bitter and it was soon realised that there would be no way to proceed to a synthesis: it would require the defeat of one of the two sides. While the socialist leadership decided to protest as early as the traditional inauguration of the king’s legislature, the anti-socialist voices coming from the press became threatening.Footnote 10 Treves already sensed, from those first warnings, that the socialists had become in everyone’s eyes the force to be eradicated by any means and that revolutionary rhetoric would end up backfiring on the party itself.Footnote 11 The Corriere della Sera called for a breakaway of the reformist wing of the official Socialist Party, to which, according to the Milanese daily, a clear alternative was opening up: on the one hand the Russian or Hungarian example and, on the other, the German or Austrian example. Thus, from many quarters, pressure was beginning to mount on Turati for a split in the reformist wing of the party, which, as we have seen, would not happen until much later.Footnote 12 However, the Corriere della Sera also underlined the inability of the liberal parties to mobilise their electorate. They considered the defeat of the liberal camp without appeal, caused by the inability to respond to discontent and face peace negotiations. In the meantime, the Popular Party presented itself as an alternative pole of attraction for all anti-socialist forces, also aiming to gather the sympathies of those who saw the need to oppose the nationalist tendencies and violence growing in those months.

Table 2 Deputies elected in 1919 elections.

| Regions | N. of deputies | Newly elected MPs | Re-elected MPs | Average newly elected | Socialists | Popular Party | Costituzionali | Other | Percentage mass integration parties | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N. | % | N. | % | N. | % | N. | % | ||||||

| Piedmont | 56 | 37 | 18 | 67 | 29 | 51.8% | 11 | 19.6% | 16 | 28.6% | 71.4% | ||

| Liguria | 17 | 12 | 5 | 71 | 6 | 35.3% | 4 | 23.5% | 5 | 29.4% | 2 | 11.8% | 58.8% |

| Lombardy | 64 | 39 | 21 | 65 | 31 | 48.4% | 20 | 31.3% | 12 | 18.8% | 1 | 1.6% | 79.7% |

| Veneto | 46 | 30 | 15 | 67 | 18 | 39.1% | 17 | 37.0% | 10 | 21.7% | 1 | 2.2% | 76.1% |

| New Provinces | |||||||||||||

| Emilia | 43 | 25 | 18 | 58 | 29 | 67.4% | 7 | 16.3% | 5 | 11.6% | 2 | 4.7% | 83.7% |

| Tuscany | 39 | 27 | 12 | 69 | 18 | 46.2% | 8 | 20.5% | 10 | 25.6% | 3 | 7.7% | 66.7% |

| Marche | 17 | 12 | 5 | 71 | 6 | 35.3% | 4 | 23.5% | 6 | 35.3% | 1 | 5.9% | 58.8% |

| Lazio and Umbria | 25 | 16 | 8 | 67 | 9 | 36.0% | 5 | 20.0% | 10 | 40.0% | 1 | 4.0% | 56.0% |

| Abruzzo and Molise | 29 | 13 | 16 | 45 | 3 | 10.3% | 1 | 3.4% | 23 | 79.3% | 2 | 6.9% | 13.8% |

| Campania | 47 | 27 | 20 | 57 | 2 | 4.3% | 10 | 21.3% | 34 | 72.3% | 1 | 2.1% | 25.5% |

| Apulia | 28 | 15 | 13 | 54 | 5 | 17.9% | 2 | 7.1% | 17 | 60.7% | 4 | 14.3% | 25.0% |

| Calabria and Basilicata | 33 | 18 | 15 | 55 | 4 | 12.1% | 28 | 84.8% | 1 | 3.0% | 12.1% | ||

| Sicily | 52 | 26 | 26 | 50 | 6 | 11.5% | 42 | 80.8% | 4 | 7.7% | 11.5% | ||

| Sardinia | 12 | 7 | 5 | 58 | 1 | 8.3% | 10 | 83.3% | 1 | 8.3% | 8.3% | ||

| Total | 508 | 304 | 197 | 65 | 156 | 30.7% | 100 | 19.7% | 228 | 44.9% | 24 | 4.7% | 50.4% |

The Revolution of the Mass Parties

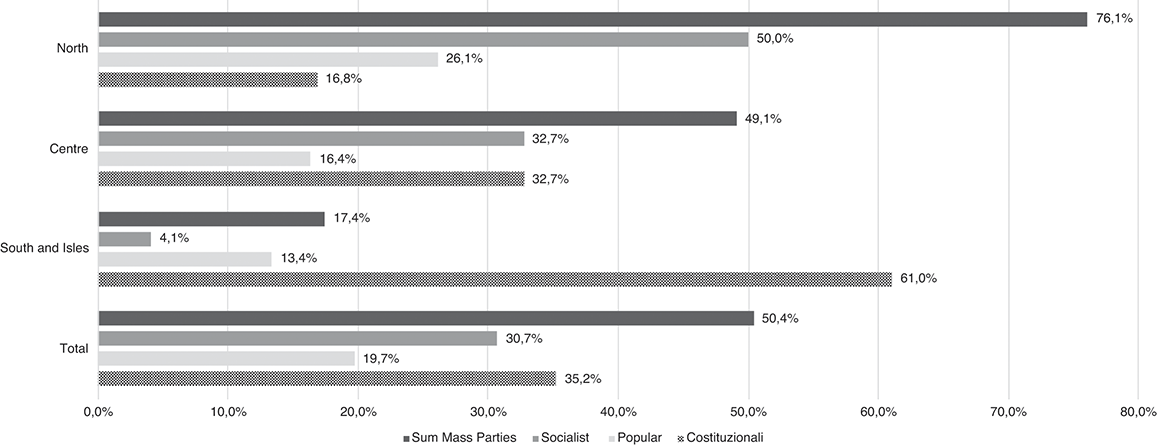

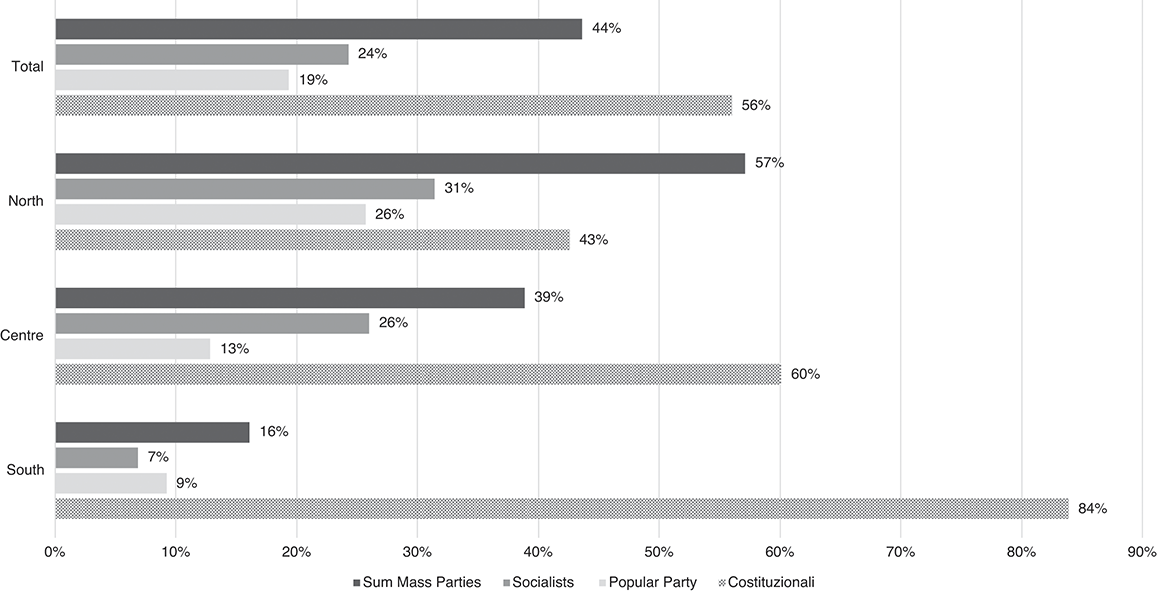

Figure 4 shows the distribution of deputies by geographical area. Thus, there is a dual cleavage – geographic and partisan – which overlap. In the north, the combined total of deputies from the Popular Party and the Socialist Party represents 76 per cent, against a national average of 50 per cent. In the south, deputies from the constitutional forces still constitute a very substantial majority (61 per cent). Another potentially alarming fact is that socialists in the north account for 50 per cent of the total.

Figure 4 Mass integration parties (Socialist and Popular) versus Costituzionali parties (north, centre, south), 1919.

The division between mass integration parties and liberals transcends mere formalities. These two spheres embody entirely different perspectives on representation. The newly emerged mass integration parties are characterised by an internal cohesion that, compared to the fluidity of the Liberals, appears uncompromising. The negotiation processes within the lower house, which were prevalent in the pre-war period, were essentially flexible. Even amidst profound ideological disparities, the liberal objective was always to amalgamate the necessary forces to reach a consensus.

Moreover, parties lacking a national organisational structure and extensive grassroots militancy for vote gathering within a context shaped by universal suffrage and mass integration found it imperative to professionalise to remain competitive (Offerlé, Reference Offerlé1999: 105–10). The contemporaries had already discerned, upon analysing the reasons for the defeat, that it was not merely a matter concerning a single party but encompassed the entirety of the liberal system itself.Footnote 13 That is, there was already an awareness among commentators and political actors of the time that a system of unrecognisable formations, assembled differently constituency by constituency, without an ideology or an identifiable programme, made the chances of victory very reduced. The Liberals accused the proportional system of having led to a situation of ungovernability but, in reality, in some ways, it had lessened their defeat. The crisis of legitimacy among the ruling classes, as manifested in the electoral outcomes, was further exacerbated by the shift from a single-member constituency, which emphasised individual candidates, to a proportional system that prioritised party representation (Leoni, Reference Leoni2001: 390).

However, it would be overly simplistic to confine ourselves to this explanation. Furthermore, as we have seen, the adopted proportional electoral system did not provide any national-level reward. Each of the fifty-four constituencies had its dynamics, symbols, and alliances, which varied significantly from one another. This allowed local notables to maintain significant control over their constituencies, as they still viewed them as their own. As a result, they felt little need to align with a more organised entity across the entire country. Senator Francesco Ruffini, in the face of this seismic event, saw the non-elective Senate as a chamber that had a function of discipline and orientation, but he also clearly recognised that a historical cycle had closed and that both the Senate and the Liberal Party would have to renew themselves profoundly. Gaspare Ambrosini – a constitutionalist – spoke explicitly of a new regime in which the old constitutional norms had passed away, having been replaced by the norms of the new constitutional system (Ambrosini, Reference Ambrosini1922). And, indeed, the consequences of the transformation on the way the political system functioned could be seen immediately. In fact, Sturzo proposed bargaining between the political groups for the formation of the government, which conditioned the Popular Party’s participation in the government on the acceptance of specific non-negotiable programmatic points (De Rosa, Reference De Rosa1972: 38), a proposal that Nitti immediately condemned, considering it detrimental to the constitutional traditions and the very rights of the Crown. It was evident that the liberal system, while partly understanding what was happening, was too sclerotic to react accordingly. As Ambrosini (Reference Ambrosini1922: 198) explained, it was impossible for them not only to accept the new status quo but even to theorise the question of the transition from a model of cabinet government, in which the leader was appointed by the king, to parliamentary group government, in which the government formation was based on the decisions of different political groups. The king’s appointment of the prime minister now had ‘to follow new procedures, dealing impersonally with the leaders of the parliamentary groups’ (Ambrosini, Reference Ambrosini1922: 187). The programme, the ministers, and the number of portfolios were negotiated with the parliamentary leaders. The already underway process will be further deepened with the reform of July–August 1920 when the Committees of the Chamber of Deputies takes on a permanent character (Orsina, Reference Orsina, Grassi, Quagliariello and Orsina1996: 397). It was decided that they would be formed not by random selection but based on political groups and that they would have significantly greater power to oversee the government’s activities (Ambrosini, Reference Ambrosini1922: 192).

An incomplete and highly contested transformation remained: it was as if there were two different and parallel systems in one country. The 1919 election marked a critical juncture in which two different political models clashed within the two countries, leading to a highly unstable political system (Istituto Centrale di Statistica, 1947: 131–2).Footnote 14 Amidst the significant transformation in the party system, one of the primary cleavages was the discrepancy between a lower house holding a majority and a Senate aligned with a different faction. With its appointive nature, the Senate appeared largely immune to the sweeping changes occurring within the political landscape. In a system of bicameralism, in which the lower house had greater powers in practice, but the upper chamber had the power to reject measures, a system incapable of functioning was created. The lower house was more supportive of measures proposed by governments led by Nitti or Giolitti, especially those aimed at increasing state intervention in the economy. However, this faced opposition from the Senate, posing a weakness the governments couldn’t afford to ignore. In the months following the 1919 elections, the perception of the end of an era was clear to the main part of the political actors. It was understood from many quarters that a complete upheaval of the landscape was taking place, marking at the same time the rejection of an entire ruling class and of the political system itself. The popular and socialist parties were the bearers of an institutional project radically different from the existing one. Whether the revolution was socialist or merely democratic or aimed at the convocation of a constituent assembly and the abolition of the Senate or its reform, it was equally unacceptable to part of the liberal world and the Crown.

2 Local Elections and the Bologna Clashes: The Rise of Paramilitary Influence

Transformations in the Representation of the Municipality

During the Italian democratisation process, the significant transformations at the local level played a pivotal role. Therefore, the local level is the fundamental observatory to comprehend the societal transformation process. The organisation of the relationship between the central state and the municipalities was inherited, at the unification of Italy, from the legislation of the Kingdom of Sardinia. Local administration was still regulated by a law from the pre-unification period of 1859 (Royal Decree No. 3,702 of 23 October 1859) which, along the lines of the French model, divided it into provinces, districts, mandates, and municipalities. Each province was headed by a governor, later named ‘prefect’ (Royal Decree No. 250 of 9 October 1861), who depended on the Ministry of the Interior, the instructions from which he had to execute. The municipal administration was then partially reformed by Law No. 2248 of 20 March 1865 which, however, kept intact all the highly restrictive criteria present in the previous legislation, both with respect to control by the central government and to the restriction of the census with regard to the electorate (Istituto Centrale di Statistica, 1947: 58).Footnote 15

The municipality consisted of a municipal council, which served as the assembly, and a Giunta, which functioned as the executive branch. The municipal councils were responsible for the ‘rules of the Charity and Charity Institutions’ (Art. 82) and it was their task to deliberate ‘the active and passive budget of the municipality, and that of the institutions belonging to it, for the following year’ (Art. 84). They were ‘subject to examination by the council the budgets and accounts of the administrations of parish churches and other administrations, when they receive subsidies from the municipality’ (Art. 83). Municipal councillors were elected for five years, 20 per cent of whom were renewed each year. If municipal councillors are not re-elected, they cannot retain their position in the Giunta. The main organ, the mayor (‘head of the municipal administration and officer of the government’, Art. 97), was appointed by the king, who also had the power to dismiss him. The mayor, chosen from among the municipal councillors, remained in office for a period of three years and was confirmed if he retained the office of councillor (Art. 98).

The expenses of the municipalities were divided into compulsory and optional. The compulsory ones were clearly regulated and constituted a long list of competencies, which included, for example, street lighting or compulsory education. Nothing was specified with regard to optional expenditure (Art. 117), but the way in which this expenditure could be financed was detailed. Art. 118, reformed in 1870, stipulated that, in the event of insufficient revenues, the municipalities could levy duties on beverages and building materials, impose taxes on the occupation of public areas or on draught animals and even dogs; and establish surtaxes on direct contributions. In essence, therefore, an important first nucleus of the welfare state developed around the activity of the municipality, which could take advantage of having broad powers both in deciding which entities to finance and how to finance them, through extended powers even in terms of taxation.

In 1889, the Crispi government approved Royal Decree No. 5921 of 10 February that introduced profound changes in the relationship between the central state and the municipalities. The electivity of the mayor by the municipal council was introduced and the term of office was reformed, making it renewable for three years (Art. 123). Secondly, a limitation to four-fifths of councillors per list was introduced to ensure that minorities were also represented. The voting system provided for a complex mechanism, whereby the voter indicated a list of names he preferred, without any indication of party, and those candidates who had obtained the most votes were elected councillors. The partial renewal of one-fifth of the councillors each year was maintained (Art. 229). The new legislation regulated the mayor’s removal process in detail. The highest representative of the municipality ‘if he does not fulfil his obligations or does not fulfil them regularly’ (Art. 52) or for ‘serious reasons of public order, or when called upon to observe obligations imposed on them by law, they persist in violating them’ (Art. 52) could be removed and temporarily replaced by the figure of the Commissioner.

Closing the cycle of a period of major reforms came Municipal and Provincial Electoral Law No. 640 of 19 June 1913, which extended universal male suffrage to administrative elections as well (Art. 28). The second article of the law contained another innovative element: it stipulated that the municipal and provincial councils, as well as the council and mayor, would remain in office for four years (revision of Art. 271) and that they would be fully renewed at the end of their term, abolishing the mechanism of partial renewal in order to give greater continuity to the administration. The counting of votes would remain as a majority, as was established in Law No. 5921 of February 1889. In accordance with these legislative reforms, all municipal councils were then renewed (Art. 3).

The Municipality, the Welfare State, and Public Entrepreneurship

The necessity for municipalities to implement increasingly expensive public services imposes significant changes in their role. Initially, it was the practice to entrust private companies with the management of a wide range of these services, such as street lighting or the construction and operation of aqueducts and tramways. However, this model had begun to show signs of crisis due to the numerous conflicts of interest that arose and the fact that it generated increased profits for the entrepreneurs that did not translate into increased quality of these services. As a result, there had been a trend towards the direct takeover of public services by the municipal administration. This change had been facilitated by an expanded reading of Municipal and Provincial Law No. 164 of 4 May 1898, which gave municipalities the right to own property and establishments.

The municipal dimension, therefore, became fundamental for socialists, both because of the pedagogical character it assumed, thanks to the small size of the territories and the direct relationship with the citizens that could be established there, and because it represented the only possibility of accessing positions of effective government of an administration, since they were still precluded from participation at a national level (Degl’Innocenti, Reference Degl’Innocenti1984: 5). The municipality, in other words, was the only place where executive functions were not strictly the prerogative of the liberal ruling classes. The municipality, then, also had other symbolic functions for socialists, including countering the centralism of power or developing a deeper idea of community (Ridolfi, Reference Ridolfi1992: 64). The history of the local government is in essence a parallel one, which developed thanks to the reform desired by Crispi and which saw Socialist representation spread like wildfire from 1889 onwards, when the ‘Reds’ decided to present themselves with their own candidates in many cities, sometimes alone and sometimes with other lists. On the other hand, the attainment of state power through the conquest of the municipalities, considered by the Socialists as the central pivot of their action and the first step of its extension, was part of the ‘minimum programme’ decided upon at the National Council of the Socialist Party meeting in Bologna in March 1895 and then ratified at the Rome Congress in 1900.Footnote 16

The implementation of municipalised companies, useful for municipalities to increase their structure, arrived in Italy with a noticeable delay, compared to countries such as Belgium or Great Britain. At the beginning of 1900, the legislative framework within which to operate was not consistently defined: the Law of 20 March 1865 No. 2248 allowed municipalities to manage enterprises directly, as long as they had a general interest purpose. To completely change the relationship between municipalities and enterprises, Law No. 103 of 1903 came into effect, drawn up by Giovanni Montemartini and desired by Giolitti, which aimed to create a legislative framework in which municipalities could municipalise public services in a specifically regulated context. The exponential growth of cities, the need to ‘electrify’ and the need to develop transport and water services made it necessary to push the accelerator of development. Private entities had hitherto been reluctant to invest and innovate and, when they had done so, the costs were significantly higher than those of direct management. Many sectors were covered by the reform, from public transport to electricity production and distribution of telephones. The passing of the law gave rise to sharp contrasts, both in the chamber and, even more decisively, in the Senate, where it passed with a difference of only eighteen votes (eighty-five in favour and sixty-seven against). The Liberals considered municipalisation acceptable only if it was in areas of ‘natural monopoly’; that is, where competition was not possible, and if it was to curb external contracting out to private companies in fields where there was a lot of investment.

The municipalised companies that had arisen as a result of this revision of the legislation were the responsibility of the municipal council, but they had a separate management structure, consisting of a director and an administrative commission. Article 13 of Law 103 also altered and innovated the system of representation, because it introduced the instrument of popular consultation (it was, in fact, a referendum, even if it was not so expressly defined) which implied a binary ‘yes’ or ‘no’ choice with regard to the resolutions of the municipal council. In order to understand the extent of the municipalisation process that took place in those years, it is useful to cite a study that came out at the same time as the law was passed by Riccardo Bachi, published in Luigi Einaudi’s journal, La Riforma Sociale. It was a long, statistical study involving over a hundred Italian cities on the issue of municipalised companies. The services managed by the municipalities at the time were mostly those of the electricity network, sewers, aqueducts, and gasometers, but there also appeared, as in Reggio Emilia, a pharmacy to distribute medicines to the poor, bakeries for the production and distribution of bread, and workshops for the maintenance of plants, as had been decided in Milan (Bachi, Reference Bachi1903: 48–9). To understand the transversal nature of the support for this type of reform, we can cite the case of Rome. Here, Montemartini himself, elected to the municipal council with the socialists, joined the municipal administration led by Ernesto Nathan in 1907. He then initiated a process of intense municipalisation, especially in the fields of electricity, social housing, and transport. To approve these projects, a popular referendum was called on 20 September 1909, in which all parties sided with the ‘yes’ vote, thus giving the consultation a foregone conclusion. There was a widespread feeling for the need to move towards an entrepreneurial municipality, driven by the large influx of people into urban centres and the need to contain their discontent. Suffice it to say that, in 1903, Schiavi (Reference Schiavi1911: 26), director of the Istituto Case Popolari (ICP) in Milan, wrote that 332,841 inhabitants (70 per cent of the population) occupied only 172,417 rooms, or an average of one room for two people. In Florence in 1907, 9,150 families lived in 6,673 dwellings. So, a few weeks after the approval of Law No. 103, Parliament also gave the go-ahead to the law wanted by Luigi Luzzatti to encourage the development and financing of social housing (Law No. 254 of 31 May 1903). The law combined the savings banks’ need to invest with the need to build houses for the intermediate and weaker social classes. Within a short time, Istituti per le Case Popolari (Institutes for Social Housing) sprang up all over Italy and soon found themselves managing not only housing but also nurseries, libraries, and schools. While the Association of Italian Municipalities was born in 1901, promoting a more inclusive idea of the city, the Socialist communes organised themselves into provincial and national federations and leagues, with the objectives, set by the General Council of the League of Socialist Municipalities, of giving each other mutual support, defending their members, and coordinating action. The conquest of the municipal administrations by the Socialists was a phenomenon that grew exponentially over the years, also thanks to the reform that had enshrined the eligibility of the mayor. Thus, the Socialists began to play a leading role in local government, managing smaller administrations then, increasingly, larger cities; first in coalition with other forces of the so-called Extreme (an alliance formed by Radicals, Republicans and Socialists) and later on their own. In November 1889, Ugo Tamburini was elected as the first mayor to lead a socialist administration in Imola, thanks to a coalition united under the name Democratic League (De Maria, Reference De Maria2010: 81–7). However, the most important victory was in Rome, where Nathan, leading a Giunta formed by an alliance of radicals and socialists, served as mayor from 1907 to 1913. After the approval of universal suffrage in 1912 and with the strong affirmation of the Socialist Party in the local elections of 1914 – the first to occur after the approval of the new law – a strong paradigm shift took place. In this context, the greatest proponents of a municipalisation of services were the Socialist administrations, especially in Emilia, which made extensive use of the 1903 laws to expand the number of services under their control, and to meet the needs of their electoral base. And, thanks to the same law, where there was hesitation on the part of the Ministry of the Interior, which, through its municipalisation offices, supervised and limited the activities of the municipalities, the legitimisation of the popular referendum often intervened (D’Amuri, Reference D’Amuri2013: 250).

In 1914, the Socialists’ strategy changed, abandoning coalitions to go it alone in the elections. In the 1914 electoral round, Socialist municipalities rose to 450 out of a total of 8,268, with a peak in Emilia where they accounted for 26.62 per cent of the total, followed by Piedmont, Lombardy, and Apulia at around 7 per cent (Ridolfi, Reference Ridolfi1992: 72). Then there was the crucial victory achieved in Milan, where the Socialists obtained 44.9 per cent (34,000 votes against 30,000 for the Liberals). Similar outcomes were seen in other cities, such as Bologna, where the Socialists won with 49.9 per cent (12,000 votes against the clerical moderates, who obtained 11,000) (Giusti, Reference Giusti1945: 56).

The 1920 Local Election Campaign

This long premise on the meaning and powers of the municipality in its dual function as local representative body and entrepreneur was necessary to understand the centrality of the 1920 local elections, which were held in a period of profound changes in the political balance. After the 1919 elections, it was clear to everyone that the north was at a high risk of falling completely into the hands of the two mass parties, the Socialists and the Popular Party. Moreover, those of 1920 were the first administrative elections after the First World War: the renewal of the municipal councils had been delayed and the scenario therefore saw 21 per cent of the municipalities governed by royal or prefectural commissioners and 40 per cent of the population administered by municipalities that had not been duly elected (Ministero per l’Industria, 1920: 50). These were highly polarised elections, held in a climate of great mobilisation and social clashes. Playing against the Socialists was the majoritarian electoral system, used to regulate the election of municipal representatives which, as we have seen, was still at that time inspired by logic unrelated to political parties; that is, it was a system in which the most popular candidates won, regardless of the proportion of their votes. It was a system that deeply damaged the Socialists, whose coalition power was in fact essentially nil. On the other hand, it was much easier in the municipal area to form large anti-socialist blocs, made up of liberals and Catholics who, contrary to the national level, had a long tradition of alliance in that dimension.

Therefore, at the core of these forces’ campaign after the shock of the 1919 elections was the objective of consolidating all available resources to defeat the Socialists, leveraging the mechanisms of the majority electoral law. The Socialist Party leadership, on the other hand, had decided that the line to be taken in the run-up to the administrative elections would be to govern the municipalities they held by aiming to solve the most heartfelt problems of social life, both through the use of the municipality as an instrument in itself and through the party’s parallel organisations, such as cooperatives and People’s Houses.Footnote 17 The Popular Party also decided to adopt the line of intransigence and thus partly breaking with tradition. The idea of the leadership linked to Don Sturzo was, on this occasion, not to ally with other political forces; a line that was not at all shared within a party that, as we have seen and will also see later, was divided internally between a more intransigent current linked to the social doctrine of the Church and a more conservative one, whose aim was to build anti-socialist coalitions with the liberals and linked to the so-called Newspaper Trust, led by the Count Giovanni Grosoli. The parliamentarians and ministers of the Popular Party were also for a broad alliance with the parties of order as they were defined by the Corriere della Sera,Footnote 18 especially as far as Rome was concerned, where it was suggested not to present a complete list of names so as to allow the liberal group to win more easily. Finally, even the Holy See seemed to be increasingly sceptical of Don Sturzo’s political line and more favourable to a policy of blocs.

The same divisions were reproduced at the level of the local elections that had been present at the national level and which were both inter- and intra-party. There were in fact three blocs – Liberal, Socialist (divided into reformist and revolutionary) and Catholic – which in turn were divided internally and without any real synthesis being possible in at least two of the blocs. In the middle of the election campaign between 19 and 20 September 1920, Turati instead gathered the members of the party’s reformist wing in Reggio Emilia. The line of the Corriere della Sera, again, was to favour a dialogue between the elements within the Popular Party and the Socialist Party, which were more willing to block against what it considered the two opposing extremes – socialist, on the one hand, and nationalist and/or fascist, on the other. Thus, it also gave Turati’s reformist congress great emphasis, with headlines occupying its entire front page.Footnote 19 The ultimate hope, not even hidden, was that Turati and his current would leave the Socialist Party.

Also playing a role in the configuration of the electoral blocs in 1920 was a clear dimension of well-defined and mutually opposing social classes. In the blocs of liberal formations, not only political organisations but also class or category organisations came together. This strategy, of course, also took into account the results of the political elections of 1919, and turned the local elections into a pronouncement that was experienced as an attempt to redeem the liberal and conservative world. Thus, for example in Turin, the Popular Party decided to be part of the ‘constitutional blocs’ because, looking at the results of the 1919 political elections, it was a city in the balance between conservatives and ‘Reds’. In Rome, the Blocco di concertazione was joined by both the Camera dell’impiego pubblico, the trade union institution that brought together public administration employees, and the Associazione dei combattenti. In Milan, the Blocco di azione e di difesa sociale list brought together almost the entire non-socialist world: in addition to the ‘constitutional’ political groups, there were the nationalists, industrialists, and a whole series of organisations linked to the middle class, from doctors to the Federal Chamber for Public Employment to shopkeepers. In Milan, but on the socialist front, the maximalists reached an agreement with the socialist centrists.

In comparison, there were in fact two different and irreconcilable models of interpreting the municipality: one, that of the socialists, who wanted to develop a plan to finance social services, and the other, that of the constitutionals formations, careful not to raise taxes and not to overstretch the municipality’s spending and interference.

The 1920 Elections, the National Blocs, and the Experiences of the Socialist Municipalities

The local elections of the autumn of 1920 constitute a sort of hinge between the phase of the Socialist Party’s rise and that of its decline. Those elections, in fact, marked both the high point of a course that had begun at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of its decline (Degl’Innocenti, Reference Degl’Innocenti1984: 12). On the socialist side there were high expectations of that electoral round, so a big leap was expected compared to 1914, when the last local elections had been held. On the other side of the political spectrum, the elections of 1920 marked the first attempt to form a bloc of agreement between Constitutionals, Popular Party, and Fascists with a purely anti-socialist aim (De Felice, Reference De Felice1965: 288).

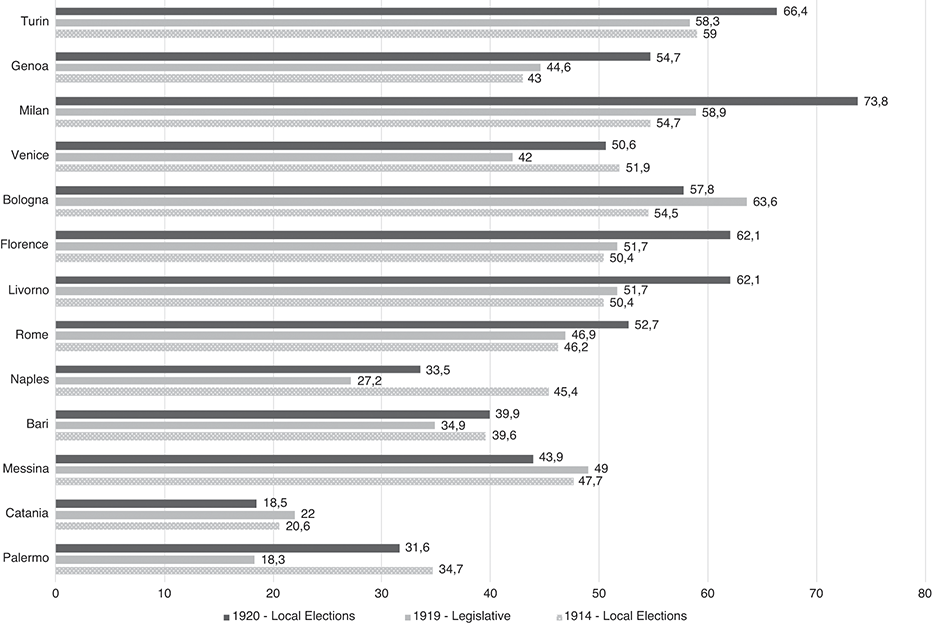

Under the new electoral law (no. 1495 of September 2, 1919), all males who had reached the age of twenty-one by May 31 of that year were included on the administrative lists for 1920. Overall, the turnout at the national level was around 54 per cent, lower than the 59 per cent in the legislative elections in 1919. This is, however, an average figure that does not capture the large differences within the various municipalities (Figure 5). Therefore, in order to get a realistic picture of the situation, it is necessary to look at the details of certain realities on a case-by-case basis which, due to their importance, took on a more symbolic character than others. In Bologna, for example, participation fell from 63 per cent to 57 per cent. In some cities, such as Catania, it barely reached 20 per cent; in others, such as Milan or Turin, it was well over 60 per cent.

The constitutional parties (Table 3), obtained the majority of councils in 4,665 municipalities (56 per cent); the Socialists in 2,022 (24 per cent) and the Popular Party in 1,613 (19 per cent). In the provincial elections, the balance was more or less similar: Constitutionalists 33 (47 per cent); Socialists 26 (37 per cent), and Popular Party 10 (14 per cent) (Ministero per l’Industria, 1920: 60). However, the results here also varied greatly from north to south, as was already evident from the results of the 1919 legislative elections. The Socialists had a majority in 28 per cent of the municipalities in Piedmont, 32 per cent in Lombardy, 26 per cent in Veneto, 52 per cent in Tuscany, and 65 per cent in Emilia. On the opposite side of the peninsula, Campania and Sardinia saw Socialist administrations formed in less than 3 per cent of municipalities, in Calabria and Sicily in less than 9 per cent. By the 1920 elections, Socialists governed a quarter of the municipalities. The difference between 1914 and 1920 in local institutions was exponential and the Socialists went from a hundred or so administrations in Piedmont to 463, in Lombardy from 150 to 651, in Veneto from 31 to 220, in Emilia from 84 to 217 and in Tuscany from 12 to 154. Overall, however, constitutional formations prevailed in the large cities: that is, in Rome, Turin, Genoa, Florence, Naples, and Bari.

Table 3 Number of municipal councillors elected in 1920 elections.

| Region | N. electorate registered electors | N. electorate eligible to vote | Voters | Average voters | Costituzionali | Populars | Socialists | Republicans | Total | Socialists (%) | Populars (%) | Sum (Socialist and Popular) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piedmont | 1,279,425 | 1,244,091 | 740,665 | 59.53% | 856 | 208 | 424 | 1 | 1489 | 28.48% | 13.97% | 42.44% |

| Liguria | 448,676 | 429,825 | 234,130 | 54.47% | 184 | 70 | 49 | 303 | 16.17% | 23.10% | 39.27% | |

| Lombardy | 1,598,537 | 1,545,288 | 998,753 | 64.63% | 706 | 580 | 617 | 1903 | 32.42% | 30.48% | 62.90% | |

| Veneto | 1,173,890 | 1,122,234 | 632,921 | 56.40% | 252 | 333 | 211 | 1 | 797 | 26.47% | 41.78% | 68.26% |

| New Provinces | ||||||||||||

| Emilia | 917,650 | 884,927 | 526,673 | 59.52% | 55 | 48 | 215 | 11 | 329 | 65.35% | 14.59% | 79.94% |

| Tuscany | 940,568 | 902,844 | 503,134 | 55.73% | 80 | 54 | 151 | 5 | 290 | 52.07% | 18.62% | 70.69% |

| Marche | 383,646 | 370,196 | 169,086 | 45.67% | 123 | 63 | 62 | 6 | 254 | 24.41% | 24.80% | 49.21% |

| Lazio and Umbria | 684,312 | 658,099 | 372,016 | 56.53% | 223 | 52 | 102 | 3 | 380 | 26.84% | 13.68% | 40.53% |

| Abruzzo and Molise | 533,627 | 523,219 | 259,824 | 49.66% | 406 | 9 | 45 | 460 | 9.78% | 1.96% | 11.74% | |