1 Sources, Methods, Contexts

While other theatrical genres from Central Europe are receiving increased scholarly attention,Footnote 1 revues, spectacles and variety shows seem to have been largely forgotten. These genres, or variants of them, were considered lower art forms, perhaps for being ‘merely’ entertaining or because they were not primarily narrative based. The lack of scholarly interest in such repertories is perhaps also due to the difficulties of researching their inherent fluidity – they constantly changed from one performance to the next. Furthermore, sources are hard to find. Librettos and scores are almost all lost. Since each production was created for the moment, preserving materials for posterity was not really a consideration. To analyse a performance, each scene would have to be reconstructed from scratch, something that is impossible due to the lack of information about many of the artists involved and their improvised contributions. Moreover, to understand the aesthetics of the revue, one must be aware of the particular dramaturgy and mechanics associated with its constituent acts, keeping in mind that entertainment is first and foremost a commercial enterprise whose goal is to make money. And whose history is this after all? Does it belong to the shows, the venues, the performers, the managers, the politicians or the audience? The answer certainly depends on the availability and types of sources.

I began working in variety shows at age nine, mostly by torturing Sunday audiences at shopping malls with my various acts. More than a decade later, studying simultaneously at the university and the State Circus School, it occurred to me that hardly anyone knew anything specific about the history of show business in Hungary. To this day, many performers argue that ‘one cannot write down such things’, but I do not share this view. Certainly, there is not one recipe for success when it comes to revues, variety shows and the like, but patterns and strategies of previous eras can be observed, identified and analysed.

My systematic research into this history began by locating and mapping the available sources in public collections. The Hungarian literature on live entertainment falls into two main categories. First are books published by a specific venue, usually written by public relations managers, not historians.Footnote 2 Second are those written by the performers themselves, which constitute much of the literature. These also lack analysis or interpretation; often are tinged with nostalgia and are primarily concerned with telling a good story.Footnote 3 The anecdotes rarely reflect on the existential and interpersonal conflicts of professional life; whatever the authors themselves did not find interesting or did not fit into their public image is conveniently omitted.Footnote 4

Such works are thus tools for nurturing the public image of their authors. Challenging and deconstructing such narratives can be a risky business, to say the least.

Before 1949, entertainment in Hungary consisted of private businesses. Therefore, surviving sources are very limited and include professional and daily press reports, memorabilia and a couple of memoirs. Many press sources are particularly problematic, since most were paid advertisements from the venues. Independent journalists faced numerous challenges, especially when it came to discussing money, since theatres were secretive about their economic situations. In 1919, when Emil Szomory (1872–1944), a journalist and theatre critic, was writing an article about the Budapest theatre business, he confessed, ‘I admit that I tried to collect exact data for this article but every manager answered the same way: the budget of the theatre is not the audience’s business because they are judging the theatre on its productions and not its ledger’.Footnote 5

After 1949, performance venues became public institutions, which resulted in there being significant amount of documentation, including tax and company reports, deposited in public archives.Footnote 6 During the 1980s, the Hungarian Theatre Institute compiled several catalogues for spoken word and operetta theatres, but regarding show venues, this ground work is mostly still missing (see supplementary material www.cambridge.org/Molnár).Footnote 7 Nevertheless, entertainment memorabilia collected by enthusiastic individuals and fans as either physical objects or nowadays as Facebook galleries offer tremendous insights into the entertainment industry. (I have amassed my own collection over the years.)

Collections and archives can reveal only part of this story. I conducted oral history interviews with former practitioners who were part of the socialist transformation and who have since passed away. The most important of these was Béla Karády (1922–2016). He was the director and artistic leader of the first municipal entertainment company to create official socialist revues. I first met Karády in 2013 (when he was ninety-one) through one of his former colleagues. I knew his name from the archives but did not suspect that he was still alive. After we met for the first time, we agreed to do so again, and we kept meeting every week or so for the next three years, until his death. Our meetings morphed from interviews into conversations between friends about past and contemporary theatre affairs. He trusted me with stories but certainly did not tell me everything. For instance, it later emerged that as a leader of a Hungarian circus company in the 1970s, he had earned a small fortune through corruption. But luckily, we met at the right moment. Karády said that if I had contacted him twenty years earlier, he definitely would not have responded. Just like my other interviewees, he needed distance and had to reach an age where there would not be consequences for talking openly about this informal layer of Hungarian theatre history. The sixty-year age gap between us was a further advantage; I did not pose any professional competition or threat but, since he did not have children, was someone who could carry on his legacy. He kept almost every document from his forty-year theatre career. I would have not known that these documents existed had I not seen them first in his garage. (See Figure 1.) Among them were several unique librettos, but unfortunately not musical scores, which seem to be forever lost.

Figure 1 Part of Béla Karády’s personal archive in his garage in 2014.

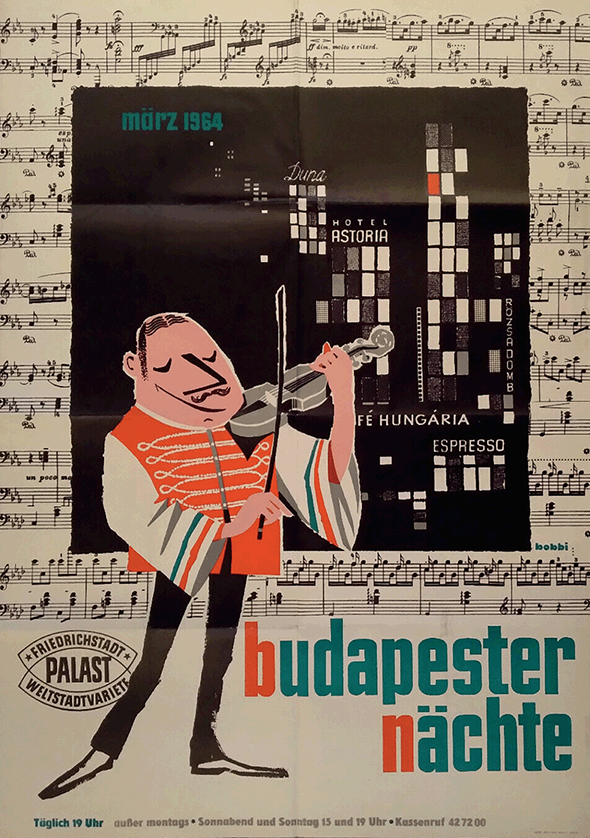

The goal of the study is to paint a picture of the cultural relevance of musical spectacles in Budapest and their place in different political–historical contexts from the 1920s through the late 1960s. The 1950s were a turning point in the genre’s history in Hungary and since many sources survive from the time, I will present these years in more detail. The underlying question is this: could the Budapest boulevard tradition fit into the cultural dictates of Hungarian Stalinism? The boulevard tradition dates back to the middle of the nineteenth century. The first large-scale metropolitan entertainment venue, the Somossy Orfeum, opened in 1894. Located on Nagymező utca, a cross-street of the famous avenue Andrássy út, not far from the Opera, the location and the building itself exuded class and quality. The area attracted several other entrepreneurs around the turn of the twentieth century, yet by the end of World War I the street had lost most of its glamour and allure.

The term pesti Broadway (Budapest Broadway) began to appear in the 1920s, first as a reference to Rákóczi út, which remains one of the main arterial roads in Budapest. In 1926, the first traffic light in the city was installed along it and various entertainment venues, mostly cinemas and nightclubs, opened on the thoroughfare. However, by the second half of the 1930s, Nagymező utca was again the centre for Budapest entertainment around the former Orpheum. A 100-meter segment of the street has been referred to as ‘Budapest Broadway’ ever since (see Figure 2). These blocks extended their aesthetic reach to the surrounding parts of the VI and VII districts, where other clubs, cabarets and music halls were located.

Figure 2 Montage of the neon lights in Nagymező utca, the ‘Budapest Broadway’, in 1938.

The word revűFootnote 8 was borrowed from the French revue, meaning ‘review’. From about 1930 to 1950, the term was not only used for grand spectacles but also for anything that in English could be described as a show. Two major types of entertainment venues were emerging at the beginning of the twentieth century: orfeum and mulató. Orpheums (the preferred English spelling) were similar to their foreign counterparts: a theatre with either rows of seats or table service that provided variety shows in two parts, each of which consisted of a series of different acts. Mulató was an umbrella term; in colloquial terms, it covered everything from nightclubs to cabarets regardless of size, and structure, whether or not they offered table service or were indoors or outdoors.Footnote 9 They were so numerous that in 1938, the Central Statistics Office reported that ‘we will not even attempt to list them’.Footnote 10

All translations in this Element are my own unless otherwise noted. Whenever possible, I refer to studies published in non-Hungarian journals and books. In such cases, their original Hungarian editions are generally more detailed than the translations.

2 From Local Importance to International Fame: ‘Budapest Broadway’, 1920–1944

2.1 Budapest Nightlife: Dead and Revived

At the turn of the twentieth century, Budapest was becoming known for its vibrant entertainment culture. Its popularity inspired Béla Zerkovitz’s 1907 couplet ‘Látta-e már Budapestet éjjel?’ (Have you ever seen Budapest by night?)Footnote 11 and the first act of Imre Kálmán’s 1916 hit operetta, The Csárdás Princess, set in a Budapest orpheum. In March 1920, however, a writer for the daily newspaper Világ published a two-column obituary for Budapest nightlife, claiming that orpheums and clubs had lost three-quarters of their audiences and that in coffee houses, ‘three waiters help take off a guest’s coat’.Footnote 12

The years between 1918 and 1920 were especially eventful in Hungary. The Kingdom of Hungary had been on the losing side in a world war, the country had gone through a revolution, a Hungarian Soviet Republic had been established and overthrown and a plundering Romanian occupation had transpired. As sa result of the 1920 Treaty of Trianon, Hungary lost two-thirds of its former territory and 3.3 million Hungarians became minorities in other states. The Kingdom of Hungary was subsequently reinstated, though without a monarch. Miklós Horthy (1868–1957), the last commanding admiral of the Austro-Hungarian navy, served as regent until 15 October 1944. A right-wing authoritarian system was established to curtail the socio-political turbulence of the previous years.Footnote 13

The mood of the 1920s was shaped by the trauma of the treaty. A crisis of cultural identity ensued: what did it mean to be ‘Hungarian’? Entertainment, which was viewed as debauchery and part of a frivolous lifestyle, was condemned by politicians on both sides: the left claimed to ‘prioritise social welfare’ over entertainment, while the right was opposed to the entertainment industry in the name of ‘Christian morals’.Footnote 14 Entertainment was set against the ‘honest, real institutions of culture’ (e.g., spoken plays), and the sphere was further demonised after cocaine and morphine began to appear in club culture around 1924.Footnote 15 On the other hand, taxes on the entertainment sector generated significant income for the city of Budapest.Footnote 16

Problems with the entertainment industry, however, dominated. The perceived need for ‘moral control’ of orpheums, cabarets and nightclubs was tied to antisemitic sentiments,Footnote 17 and even though show business was not responsible for the coal or apartment shortages, the idea of a wasteful nightlife (and the associated image of those who could afford it) became a perfect scapegoat for social ills. Government-mandated closing hours, higher taxes and another wave of the Spanish flu also negatively affected nightlife. Furthermore, several leading founders – managers of the previous era (e.g., Dezső Gyárfás, Dezső Bálint, Imre Waldmann) died during the decade.

Very few people could afford a night out. In the 1920s, Budapest was a city of refugees and poverty; it did not take much to get beaten or stabbed at night. Due to immigrant and employment crises, many newcomers had to work at night in jobs for which they were often overqualified.Footnote 18 The main clientele for nightclubs, the middle class, if they were not working at night, could afford only orpheum entertainment, which, since it was not tied to food and drink, was less expensive. Many journalists at the time saw the middle-class situation as the reason Budapest nights were silent.Footnote 19 As Andor Kellér, a well-renowned journalist and writer of the time, put it:

Abroad, if someone goes out to have fun, they devote a certain sum to having a good night. Money that is not for anything else, that is not supposed to cover the tailor’s bill. … The difference is that the Budapest audience does not spend its spare money at the clubs but instead on the down payment on the fur, the rent, the gas bill and the tuition for a young student. … Historians of the future will understand Budapest nights … from this adage: ‘Oh my God, if we could live the way we’re living.’Footnote 20

Night-time entertainment began to belong to the aristocracy, especially its young people, including teenagers.Footnote 21 Clubs became places for the young rich elite to meet, venues where one’s behaviour was now less bound by customs and protocol than had previously been the case.Footnote 22 This change is likely rooted in the fact that the aristocracy no longer had the political clout to justify its extravagant lifestyle.Footnote 23

Politicians saw many of these cultural challenges as clashes between the ‘Hungarian’ and the ‘foreign’ and thought that genres and styles considered ‘traditionally Hungarian’ must be defended at all costs. This viewpoint was especially evident when it came to the increased popularity of jazz in Hungary, a style that was regarded as the antithesis of traditional ‘Hungarian Gypsy music’ and a threat to it.Footnote 24

When Imre Magyari and his Gypsy Band were denied permission to perform in London (though they played in Liverpool),Footnote 25 the Ministry of Internal Affairs saw an opportunity to influence the Budapest music scene. The Ministry proposed an edict banning foreign musicians from performing in Hungary and expelling the sixteen (Black) jazz musicians then playing in the city. The possible repercussions, namely that Hungarian artists and musicians would likewise be banned abroad, prevented the edict from being as restrictive as originally planned.Footnote 26 Another new edict regulating the employment of foreign artists introduced an elaborate and off-putting bureaucratic process for both managers and artists ‘to defend the workplaces of Hungarian workers’.Footnote 27

Another major cultural challenge related to the Hungarian-foreign question took place in the operetta realm. In 1922, the American theatre entrepreneur Ben Blumenthal acquired the Fővárosi Orfeum (Municipal Orpheum; opened in 1894) and reopened it as Fővárosi Operettszínház (Municipal Operetta Theatre). The change was closely watched. The professional organisation of non-actor performers, Magyarországi Artisták Egyesülete (Association of Artists in Hungary, MAE), mourned the loss of the first music hall in Budapest, since the new profile meant lost work opportunities for its members.Footnote 28 Many politicians considered theatre as a tool for creating and nurturing national identity,Footnote 29 so it was easy to interpret Blumenthal’s actions as a corruption of Hungarian culture.

In 1924, Blumenthal attempted to introduce a business model similar to those of Broadway theatres and Parisian music halls. Instead of having several rotating productions per season, only one production would be staged at a time, a large-scale feast that could hopefully run for years. The first of these was Halló, Amerika! (Hullo, America!), which opened on 30 January 1925 and was introduced in the press as representing a new genre: the revue.Footnote 30 This production revived the antisemitic sentiments against Blumenthal in the right-wing press and again set up an opposition between ‘Hungarian’ (operetta) and ‘foreign’ (revue) genres and cultures. Meanwhile, theatre-sponsored articles and liberal journalists argued that staging a revue was raising Budapest to the level of other European capitals, although they ignored the intercultural conflicts and brutal behaviour of the show’s American director. The star performers stood against the revue approach because its real protagonists were the chorus girls and the spectacle – not them.Footnote 31 Halló, Amerika! was a financial flop. The Budapest audience could not keep the show running for even six months, particularly during this time of hyperinflation. Despite losing money and the political hysteria surrounding it, Halló, Amerika! was a spectacle of previously unexperienced size and quality in Hungary and had an enormous cultural impact. In the months that followed, Halló, Amerika! was referenced, copied and parodied in Hungarian-language theatres inside and outside Hungary. The show introduced Budapest to the concept of modern revues, added the technical term görl (showgirl) to the everyday Hungarian vocabulary and popularised the idea of a show business career for young women.

The question of whether revues could become ‘Hungarian’ was still being asked at the end of the decade. In 1928, the Operetta Theatre attempted to turn its attention again towards spectacular staging. Mihály Eisemann’s Miss Amerika featured sixty showgirls, 400 costumes and a camel borrowed from the zoo. The production did not receive any negative reviews; in fact, its run was supported by a press campaign (following the lead of Halló, Amerika!), this one celebrating Hungarian invention and fantasy with rumours of a transfer to Vienna or Berlin, though neither happened.Footnote 32 An unnamed writer for the Budapesti Hírlap (Budapest News) wrote,

Budapest does not want revues created in the spirit of Western metropolises, but rather Hungarian revues, since Hungarian authors are reformers of the field. Hungarian authors write operetta librettos with a complete story, which they split into scenes and dress in the colourful cloak of the revue.Footnote 33

Although billed as an operetta and having an entirely Hungarian cast and creative team, the key to the show’s success was not its narrative elements but rather its staging. Ernő Szabolcs, who directed the production, had worked alongside with Jack Haskell on Halló, Amerika! and even inserted a showgirls-on-ladders scene similar to one in the 1925 revue. The production came across as something distinctively ‘Hungarian’ in a modern, cosmopolitan style. It was the success of the year and established Eisemann as an operetta composer.

Around 1925, things slowly began to change in nightclub culture. It was again safe to be out at night thanks to the bright newly installed neon-lit advertisements. The pre-war békebeli (peace time) nightlife had become a subject of nostalgia,Footnote 34 and from 1927, the IBUSz (Tourism Office) organised night-time bus tours around the city that included visits to four clubs.Footnote 35 The former coffee house in the building of the Operetta Theatre was remade into a luxury nightclub with the name Moulin Rouge. Its parquet floor was covered with crystal glass illuminated from below, providing a unique atmosphere.

With the political consolidation, debates around the legitimacy of entertainment ceased but not ones about its content. In 1927, the Minister of Internal Affairs introduced a moral edict, instructing the police to increase control over all public performances.Footnote 36 The edict targeted primarily Budapest. It was daunting and far-reaching and penalised certain individual behaviours. Swearing in public and ‘dancing publicly in a way that offends good taste’ were prohibited. In the following months, nightclub posters found to be ‘indecent’ were removed, and a production of Finom kis lakás (Poulet de luxe by Auguste Achaume) at the Operetta Theatre was even closed. The edict was ridiculed in both the Hungarian and the international press, especially after a bookstore was prosecuted for putting a book in the shop window with Venus de Milo on its cover.Footnote 37 The edict was never revoked but the enthusiasm for following it faded into indifference within a couple of years. Among its long-term results, it decreased the respect towards the police (which followed the edict) and the number of syphilis cases rose due to secret prostitution.Footnote 38

The edict’s effect came to the fore when the international superstar Josephine Baker (1906–75) included Budapest on her first Central European tour. Her April 1928 performances at the Royal Orfeum and the Moulin Rouge met with loud resistance from conservative politicians on both racial and moral grounds.Footnote 39 This was a delicate issue because she had signed a contract with the Royal Orfeum, a private business, with which the government attempted to interfere. She agreed to have a closed ‘exam’ performance for high-ranking police officers and Ministry officials, who in the end did not chastise her performance. One of them even remarked, ‘I’ve seen several more naked dancers than this!’Footnote 40 The political hysteria generated around Baker’s visit only enhanced the singer’s popularity, which resulted in her shows selling out faster than they would have otherwise. At her fourth public performance, a group of university students threw stench bombs into the audience, but this was the only disturbance during her stay.Footnote 41 An added benefit of the hysteria was that Béla Zerkovitz, manager of the Royal Orfeum, composed an advertising foxtrot, ‘Gyere, Josephine’ (Come Josephine), which became one of the singer’s standards when she performed it in French as ‘Dis-moi Joséphine’.Footnote 42 Politicians took no notice of her return the next year nor her third visit in 1934.

One of the venues where Baker performed, the Royal Orfeum, dubbed the ‘National Theatre of Artists’, opened in 1908. It was the largest music hall in Budapest with roughly 1,000 seats, similar in capacity to the Operetta Theatre. Its variety show format did not change significantly over the years: twelve to fourteen acts, split into two parts with an intermission. The programme changed monthly. Since Zerkovitz was keen on engaging the biggest names, all the major continental artists appeared, including the comic acrobats Rivel Brothers, the juggler Rastelli, the clown Grock, the French vedette Mistinguett and the magician Okito. In 1929, Zerkovitz attempted to shift from variety shows to revues, but abandoned the idea after just one production, Start! The show only ran for a month, and a year later Zerkovitz gave up managing the theatre in order to prevent further losses. This had nothing to do with the aforementioned cultural dispute: the ‘Hungarian’ quality of his shows was never an issue. It was because he realised that people in Budapest could not afford the high ticket prices that were necessary in order to pay these stars and sustain the theatre long term.Footnote 43

The new manager, Mihály Schmidt, came from the circus industry and implemented a different business model. He aimed for cheap entertainment with two shows a day.Footnote 44 But while this was possible for circuses and sideshows in outlying districts, the Royal was a major theatre with significant running costs and a different, multi-layered audience. Within a couple of months, Schmidt decided to also engage music hall stars, including the juggler Sylvester Schäffer Jr, the magician Kassner and the international dancing sensation Marika Rökk. Schmidt shifted his focus in 1932 by booking touring spectacles such as Doorlay’s Non-Stop Revue Tropical ExpressFootnote 45 and a Viennese hit, Küsst österreichische Frauen (Kiss Viennese Women). His biggest success, however, was an original production, Tessék beszállni! (All Aboard!), in 1933 (see Figure 3.).Footnote 46 Schmidt’s major source of revenue was renting out the theatre for boxing and wrestling matches, since Budapest did not have a dedicated, suitable venue for such events. The Royal Orfeum was still far from profitable, and Schmidt went bankrupt. He gave up the house in 1934 to pay off his debts and for treatment for the health issues he developed during his managerial years. Although he, like Zerkovitz, tried several different artistic-business strategies, none of them worked. The problem was the financially strapped Budapest population, an insolvable dilemma.

Figure 3 Playbill cover for Tessék beszállni! (All aboard!) by Alfréd Márkus, starring Lici Balla.

The 1930s were a critical period not only for variety shows and revues but also for the so-called national genre, the ‘Hungarian’ operetta, which was almost fetishised a few years earlier. The Operetta Theatre went bankrupt in 1935. Én és a kisöcsém (Me and My Little Brother) by Mihály Eisemann had been a success the previous year,Footnote 47 but due to the management’s overall financial instability, the flop of the next production, Grand Café, was enough to put the theatre out of business. The same thing happened to the other major operetta theatre in town, the Király Színház (Király Theatre). Its final decade existed in complete agony, with six different managements in eleven years. After it closed in 1936, several luminaries reflected on the operetta crisis, looking beyond the lack of capital. The playwright and humourist István Békeffi claimed that the spread of movies with synchronised sound (talkies) had resulted in a loss of audiences for operettas.Footnote 48 Sándor Incze, the editor-in-chief of the most influential theatre magazine, Színházi Élet (Theatre Life), blamed the decline on a lack of stars, who either chose better-paying foreign engagements or emigrated.Footnote 49 The operetta historian Gyöngyi Heltai asserts that social attitudes also played a major role. The political elite did not separate operetta from national culture but neither did they make any efforts to sustain the genre. Neither audiences and critics nor performers supported the attempted changes in style. Budapest audiences demonstratively rejected the modern stagings that alluded to contemporary domestic and foreign affairs. These were not what audiences expended. They clearly preferred nostalgia-tinged productions and disliked any attempts to modernise either the content or the form of the genre.Footnote 50

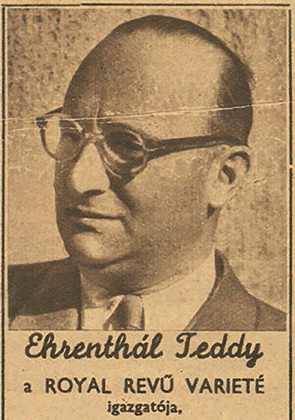

Despite financial losses and critical failures, entrepreneurial enthusiasm remained high. After every bankruptcy there were potential leaseholders for empty theatres, Hungarians and foreigners alike. Bernardo Labriola, the manager of the Ronacher Theater in Vienna, attempted to expand his business in Budapest by opening a music hall. Likely inspired by the German concept of Großvarieté (producing variety-style shows for audiences of 3,000), in 1932 he took over the largest theatre in the city, the Városi Színház (City Theatre), which had about 2,000 seats. The plan did not work; his venture folded the next year. In July 1935, Teddy (István) Ehrenthal, a Hungarian agent with theatrical interests in Paris, announced that he would rent the Operetta Theatre building for six years and run it as a music hall. He renamed it the Fővárosi Orfeum and even managed to engage the Hollywood film star Ramón Novarro to perform there. Ehrenthal, however, became embroiled in a scandal: he did not have the money to pay the contracted artists, fled the country, was arrested in Vienna and extradited to the custody of the Hungarian police.Footnote 51 In 1936, Philipp Lesing, manager of the Liebig Theater in Breslau (today Wrocław, Poland), reopened the Király Színház as Fővárosi Orfeum. The enterprise lasted two days.

Since theatre entrepreneurs lacked capital, it was impossible for them to run a stable business.Footnote 52 Theatre journalist Sándor Incze noted that entrepreneur-managers were not the only ones to blame. One also had to consider the theatre owners: in America, the theatre owner even helps out certain talented producers financially. In our midst, they find it natural that a leaseholder candidate sits down to negotiate with only the advance payment of the ticket office, the cloakroom and the buffet in his pocket.Footnote 53

Building owners were more focused on short-term income than on long-term artistic and business goals. By the middle of the 1930s, only occasional summer open-air venues mounted large-scale productions. As Variety put it:

Not one big vaudeville or variety theatre has been playing in Budapest for years. Instead, night club (sic) floor shows have attained a very high standard and unequalled popularity.Footnote 54

It is to these nightclubs we now turn our attention.

2.2 World-Famous Wonder Bars

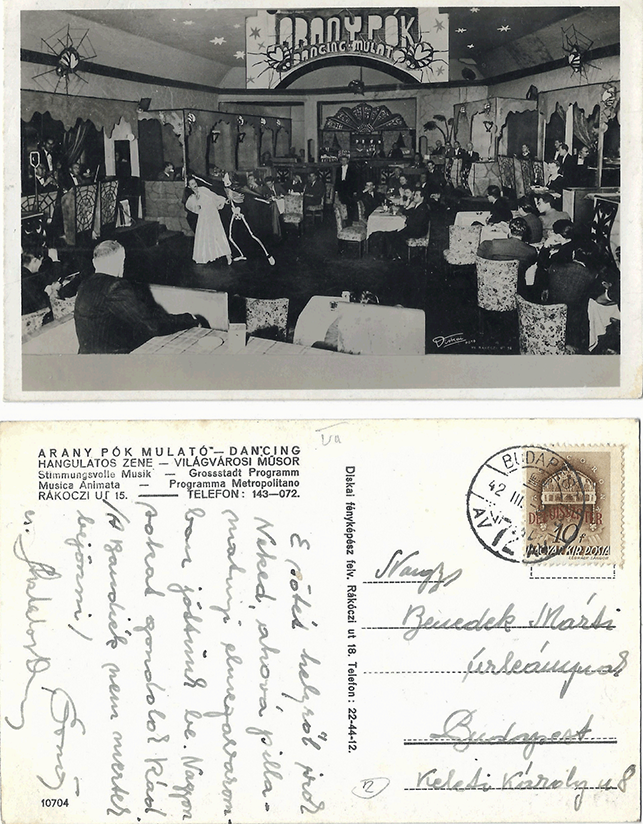

During the 1930s, Budapest’s show business reached international fame in the Western world through its luxurious nightclubs. Apart from the experience and business acumen of a new generation of managers, international circumstances were in its favour. After Hitler rose to power in 1933, the liberal and (in-)famous Berlin club culture of the ‘goldene Zwanziger’ (the golden twenties) was over. Budapest, traditionally considered to be on the edge of Western Christian culture, provided an exotic setting where a night out was significantly cheaper than elsewhere in Europe. By 1935, it offered a wide selection of high-quality spectacles. Nightclub shows were not new, but their scale and quality reached new levels. Shows were reviewed in Variety and Billboard and by the continental press. Foreign papers highlighted their cosmopolitan nature, while Hungarian ones emphasised their local value. Smaller clubs billed themselves as világvárosi szórakozóhely/műsor (global city venue/show), implying nostalgically that Budapest was still a centre of cultural-political influence.Footnote 55 The interior design of clubs was a cardinal question. Aside from being functional, the decor had to create a distinctive atmosphere, one which also served as a permanent set for the stage showsFootnote 56 (see Figures 4 and 5). For example, the Jardin d’Atelier was inspired by a French village, while the Sanghay was richly decorated with chinoiserie and the Capri evoked a dripstone cave. Major clubs also ran summer venues either on Margaret Island (e.g., the Parisien Grill from 1931) or in the Városliget (City Park). Open-air clubs like the Plantage Bar or the Jardin de Paris were only open during the summer months.

Figure 4 Postcard showing the interior of the Aranypók (Golden Spider) Dancing, 1942. Message: ‘To Miss Márti Benedek / I’m writing to you from this dark place where we entered in a sudden confusion. I’m thinking a lot about you. (Bandi and the others did not dare to enter.) Kisses, Ernő Dénes Asztalos’.

Figure 5 Postcard showing the interior of the Jardin d’Atelier, 1936.

Although the Minister of Commerce expressed that Budapest, besides its spas, should be known as ‘the city of entertainment’,Footnote 57 this did not mean that nightlife would be supported by the state or the municipality in any way. Nonetheless, ‘Budapest Broadway’ and its clubs appeared in official tourist pamphlets and guidebooks.

In 1931, after the suicide of the previous manager, Ernő Flaschner took over the Moulin Rouge. Like him, many of the new entrepreneurs had worked as waiters in the 1920s before they opened their own clubs.Footnote 58 Flaschner assembled a more or less permanent production team to provide interactive spectacles for his guests. He considered his venue a theatre; at its peak, a cast and crew of 120 were involved with the shows, which he called lokálrevű (nightclub revue).Footnote 59

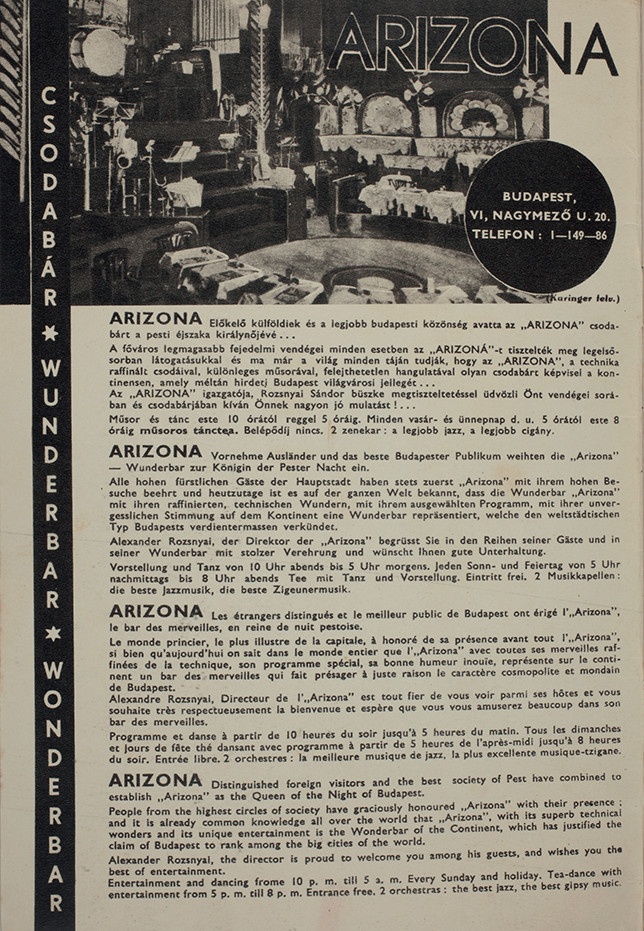

Another manager, Sándor Rozsnyai, began his career as a musical parodist and conductor. He had a double act with his wife, who was known by her stage name, ‘Miss Arizona’. After touring for about fifteen years, in 1932, they bought the house opposite the Moulin Rouge, in which they opened the Arizona Revue Dancing.Footnote 60 Miss Arizona was the star of productions, although her artistry was not the main draw. Their shows relied primarily on the acts featuring the showgirls – who at one point were hanging upside down from a chandelier – and the theatre’s technology. The main attraction was the revolving parquet dance floor, which could also be lowered and raised. Furthermore, the side boxes could be hidden with the push of a button. In 1935, the couple launched a marketing campaign using the word csodabár (wonder bar), an epitheton ornans which they used, and others copied until the end of World War II.Footnote 61

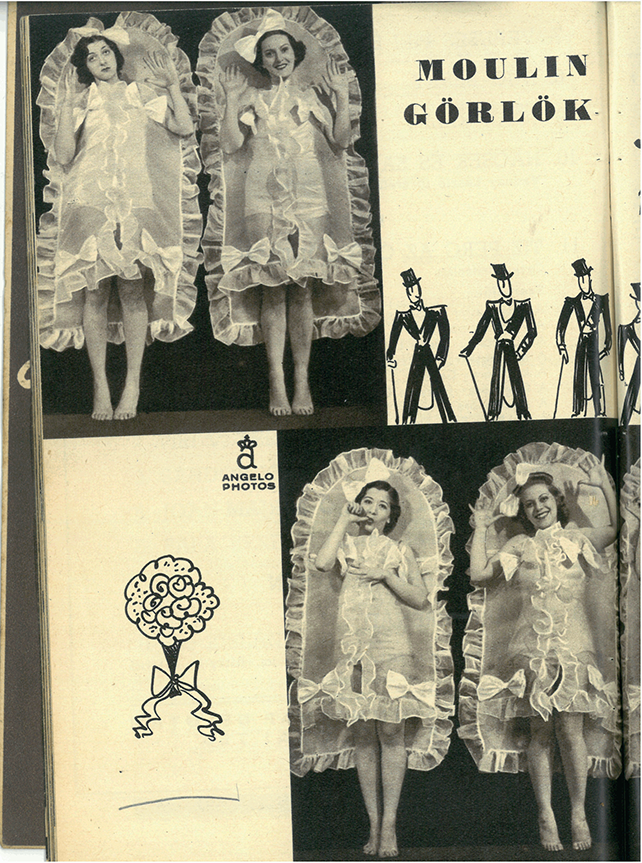

By 1935, the Arizona Revue Dancing and the Moulin Rouge could each accommodate about 200 guests, which in the case of the Moulin Rouge doubled by 1943.Footnote 62 Their business models were similar: entrance was free, though purchasing food and drink was expected and encouraged.Footnote 63 Both clubs relied heavily on the objectification and extreme exploitation of young women. Several similar venues tolerated prostitution, both male and female.Footnote 64 A double standard regarding public morals existed: while nudity and sexualisation were explicit on stage and in the playbills, the first Hungarian ‘men’s lifestyle magazine’, the Playboy-like Új Magazin (New Magazine) was banned from publishing such pictures taken by the same photographer. Both clubs produced a new show every month, unless the previous one was so popular that it was extended. At the Moulin Rouge, shows began around 10 p.m. and the second part started after midnight; the Arizona Revue Dancing advertised itself with ‘a new attraction every 15 minutes’. In 1937, a Moulin Rouge playbill was 64 (!) pages long. While the Arizona’s was shorter, it was covered in photos. They also served as a souvenir and advertised the venues in four languages (Hungarian, French, English and German; See Figure 6).Footnote 65

Figure 6 Page from the four-language playbill of Arizona Revue Dancing, 1935.

The usual closing time for both clubs was 5 a.m. From 1934, on Sundays and holidays, five o’clock teas with a full show – practically matinees – were also offered for those who preferred not to stay out all night. Mondain dance novelties – like the beguine, the rumba and several others developed in-house – were introduced in club productions. Between acts, customers danced to the music of Hungarian jazz bands. These bands achieved international fame and were frequently heard on the Budapest Radio and the BBC.Footnote 66

To satisfy demands from both locals and the international clientele, ‘Gypsy’ bands were also featured. The Moulin Rouge produced the first ethnic-inspired showgirl act in April 1937. It included traditional steps and visual designs and claimed to represent authentic Hungarian folk culture. The concept was copied by every major venue in town, except – significantly – the Arizona.

Originally both the Moulin Rouge and the Arizona targeted the local upper middle class, but by 1935, both became known as regular informal meeting places of the elite, not only the monied but also the politicians.Footnote 67 István Bethlen Jr, son of the Prime Minister, fondly remembered his visits to the clubs:

I think I was the first playboy in Hungary. … My father was the omnipotent Hungarian Prime Minister and I, his omnipotent son. My father was the friend of (Regent) Miklós Horthy, and I was the best friend of Pista Horthy (his son). So while the old men did the politics, we spent our time in a much smarter way. Oh, pal, those were good times! When Pista Bethlen and Pista Horthy went to a nightclub, every night fairy who was worth something clattered and even the gypsy carrying the double bass stuffed himself with foie gras and drank champagne. On my right knee, a blonde was sitting; on the left a brunette, while I was hugging a raven-haired with my left arm and a redhead with my right.Footnote 68

The British fascination with Hungary grew in the late 1920s, thanks largely to Lord Rothermere, who was a loud supporter of Hungarian revisionism.Footnote 69 The visit(s) of the Prince of Wales, the future Edward VIII,Footnote 70 gave it a further boost. Budapest nightlife became the subject of English-language reports, travelogues and novels.Footnote 71 Numerous Hungarian novels were set partially or entirely in nightlife by Erzsébet Barra, Andor Kellér and Tivadar Zichy to name a few. Stage plays and films also capitalised on the subject starting with the second Hungarian talkie, Hyppolit, a lakáj (Hyppolit, the Butler, 1931), Havi 200 fix (Salary, 200 a Month, 1936) or Egy nap a világ (There’s Only Today, 1944).Footnote 72 A French (Retour à l’aube, 1938) and as well as an American film (As You Desire Me with Greta Garbo, 1932) were set in Budapest nightclubs. An article in the American fashion magazine, Vogue also praised the city’s nightlife in March 1939.Footnote 73

2.3 The Restrained and ‘Adjusted’ Show Business

The 1938/XV. Act, established to ‘secure the balance of social and economic life’, became Hungary’s first (explicit) anti-Jewish law. It set a maximum percentage of Jews who could participate in public life. A year later, a second anti-Jewish law banned Jews from every position ‘which influences the employment of artists or the artistic direction of a theatre’.Footnote 74 The 1938 act established various profession-based bodies (called chambers) whose purpose was to exclude Jewish artists and intellectuals. The Színház- és Filmművészeti Kamara (Chamber of Theatre and Film Arts) was charged to ‘ensure the demands of national spirit and Christian morals’.Footnote 75 The process was referred to as átállítás (‘adjustment’), but it was clear that the complete and immediate implementation of these laws would have paralysed the theatre and film industries. Far-right and antisemitic papers complained that nightclubs, either through straw men or directly, were still being managed by Jews. Indeed, managers found legal loopholes to keep their businesses. For example, Sándor Rozsnyai registered the Arizona under his wife’s name. Shortly afterwards, he was drafted for labour service alongside his son, who died of suicide rather than having to serve.Footnote 76

Ernő Flaschner could have remained in charge of the Moulin Rouge until 1942 and still have employed several Jewish artists. A management change, details of which are unclear, took place. In the end, the far-right sympathising headwaiter-turned-entrepreneur János Nedeczvári replaced Flaschner. The house was renamed its Hungarian equivalent, Vörös Malom, and nationalist overtones were added to the show. Claiming national pride, artists with foreign names were pressured to adopt Hungarian ones.Footnote 77 Showgirls had to appear by their given names, for example, Márta Mázik instead of ‘La Bella Marta’. This looked particularly grotesque in the case of married women who used their husbands’ names; for example, one showgirl was credited as ‘Mrs Wiesner’.

Music halls and clubs did not fall under the jurisdiction of the Chamber, which had a hostile attitude towards them. In 1941, the jazz musician Sándor Heinemann managed to successfully reopen the Royal as Revűszínház (Revue Theatre) and produce shows there each month; however, the Chamber protested against the use of the term ‘theatre’. In March 1943, its name became Revűpalota (Revue Palace), even though the venue was not a nightclub but a 1,000-seat theatre.Footnote 78

The Chamber also influenced the venue’s employment policy. The management had to submit a report to the Chamber listing their contracted performers. For the opening production in September 1941, the Chamber only objected to one artist, Ernő Szabó, whose appearance was ‘not recommended’.Footnote 79 The reason is unknown; Szabó was an established actor from a theatrical dynasty, and his engagement at the Royal had been announced in July.Footnote 80 Furthermore, he was a member of the Chamber and had even worked at the Royal the previous season. In 1941, Szabó was a member of the theatre company in Nagyvárad, a Transylvanian town which had been returned to Hungary the previous August. Perhaps the Chamber thought that promoting Hungarian culture in Nagyvárad was more important than an occasional performance in a Budapest music hall. The Chamber’s rejection of Szabó’s employment arrived only three days before opening night, a verdict that likely caused a severe headache for the management.

The Chamber lobbied each year to take over entertainment venues for their own purposes, but the MAE managed to defend the interests of the artists. (Music hall licences were granted formally by the police on the recommendation of the Chamber.) Many banned Jewish artists, including the operetta star Rózsi Bársony and the comedian István Békeffi, became members of the MAE, which out of solidarity allowed them to keep performing. According to the 1944 report, 150 Jews were among the 2,000 members of MAE.Footnote 81 As a result, the association was heavily attacked by the far-right press. The Chamber also lobbied against the MAE, which resulted in the Minister of Internal Affairs ordering that monologues, couplets and solo acts ‘belonging to theatre arts’ could only be performed by members of the Chamber.Footnote 82 The MAE protested against this unreasonable restriction, especially because employment for artists had become very difficult after Hungary entered World War II in the summer of 1941.

On 19 March 1944, the German Reich invaded and occupied the Hungarian Kingdom. The Minister of Internal Affairs immediately closed all theatres and performance venues for a week, during which it reviewed employment records and deposed all Jews from music halls. As a result, several venues closedFootnote 83 and remaining ones had significantly fewer customers.Footnote 84

The Hungarian National Socialist force, the Nyilaskeresztes Párt – Hungarista Mozgalom (Arrow Cross Party – Hungarist Movement) had a particular vision for the future of Budapest entertainment. The party’s paper, Magyarság (Hungarians), proposed transforming music halls into ‘literature cabarets with an articulated spirit’ led by ‘pure Aryan and nationally committed professionals’.Footnote 85 Furthermore, the new mayor of did not see the city’s nightlife as a defining part of its future:

This city is in the state of being reborn. Likely, this capital, whose beauty lies in its natural treasures and human creations, will not be famous for having lots of silver-mirrored coffee houses. … People might say that there are few theatres and few nightclubs. They might. That’s all right. The Budapest of the future, the capital of Hungary, should be famous for her other virtues.Footnote 86

Heinemann closed the Royal in April to avoid being accused of employing Jews. The Nazi leisure organisation Kraft durch Freude (Strength through Joy) took over the theatre in June and under the name Magyar-Német Katonaszínház (Hungarian-German Military Theatre) produced opera and variety shows until mid-December 1944, except in September, when the Minister ordered every club and bar closed.Footnote 87 This decree of 2 September 1944 came one week after Goebbels announced the closure of German and Czech theatres. Budapest theatres reopened in October, but not the clubs.

On 15 October 1944, Regent Miklós Horthy announced that Hungary had signed a cease-fire with the Soviet Union. Blackmailed by the Nazis along with his son, he renounced the armistice on the same day and abdicated in favour of the Arrow Cross Party leader, Ferenc Szálasi, who became prime minister. The Hungarist Government’s authority was limited to the territory around Budapest, and its rule was brutal. Deportations and death squads were commonplace, and the Danube became filled with corpses, including that of the prima donna–entrepreneur Miss Arizona. Her husband was likely killed in a concentration camp. On Christmas Eve, the Soviet siege of Budapest began. When it ended on 13 February 1945, Budapest lay in ruins. Roughly 80 per cent of its buildings were destroyed or damaged, as well as all seven bridges across the Danube.

3 Revues in Crisis

As a result of the war, 40 per cent of Hungary’s national wealth was depleted and 6.2 per cent of the population perished. Soviet troops were looting and raping on the streets of Budapest, and plans were being made in Moscow to make the country a Soviet satellite state. Still, the transitional phase that lasted until 1948–49 was characterised by an economy that still avowed market mechanisms and political–cultural pluralism.Footnote 88 In 1946, the Republic of Hungary was declared. The Paris Peace Settlement cemented the borders of the country to their pre-1938 state, repeating the trauma of 1920. The communist takeover accelerated after 1948, and a year later the new constitution established a Soviet-type totalitarian dictatorship under the Magyar Dolgozók Pártja (Hungarian Workers’ Party), led by Mátyás Rákosi (1892–1971), known as ‘the best pupil of Stalin’. Hungarian society was restructured to destroy ‘the bourgeoisie’ and marginalise the traditional elite.Footnote 89 Heavy industries were prioritised, making Hungary ‘the country of iron and steel’, and the minimal production of consumer goods resulted in frequent shortages.

3.1 A Dubious Legacy

After the Soviet occupation of Budapest, the Mayor ordered a tabula rasa for theatres. Entertainment and its cultural place and role were again being debated at local (municipal) and national (ministerial) levels.Footnote 90 The political attitude toward the legacy of club culture and nightlife was hostile, for clubs were still associated with the privileged, so much so, that even representatives of the liberal party were supporting and demanding the investigation of their clientele.Footnote 91 The only counter-argument was the financial interest of the city: entertainment and luxury taxes still brought in significant income. After a communist mayor came to power in 1947, the party made a U-turn. They began campaigning for lowering and ultimately abolishing the entertainment tax, but the idea of ‘educational productions’ was behind this egalitarian approach.Footnote 92 Police oversight was normal, although closing times were not always respected by the policemen themselves.Footnote 93

Several clubs reopened after the war, mostly under new managers who were willing to continue the established brands. In such an environment, no new clubs opened. When clubs reopened, they were on a significantly smaller scale than before. The floor shows reflected the changing political-social system, which would not allow any sort of Arizona Revue Dancing- or Moulin Rouge-style enterprise. This went along with the fact that the opulent lifestyle of their audiences had also disappeared. Furthermore, the new managers lacked the capital and imagination of their predecessors.

Under the new regime, Sándor Heinemann was not allowed to continue managing the Royal because he exposed himself propagating the war.Footnote 94 Instead, the licence was given to László Gonda, who was supported by the newly organised trade union of artists. However, even this decision was overturned a couple of months later, and the theatre landed in the hands of Teddy Ehrenthal in acknowledgement of his services translating for the leaders of the Soviet army.Footnote 95 His networks and back-room deals turned out to be so much stronger than the lobby of the party-supported trade union that the union had to ignore his criminal past. He held the Royal’s licence for the next four years, and in August 1946, acquired a licence to reopen the Moulin Rouge. Its former manager, Ernő Flaschner, survived the war and – perhaps unwillingly – relinquished his contractFootnote 96 to the Bureau of Soviet Assets in Hungary.Footnote 97

Singers, comedians, dancers and jazz musicians dominated the nightclub offerings. Sketches ridiculed fascist leaders and politicians, something that had not been allowed publicly for years. Dancers learned new steps seen in Hollywood films, which were being screened until the Stalinist turn. Jazz historian Géza Gábor Simon describes the period between 1945 and 1950 as the ‘golden era’ of Hungarian jazz: György Cziffra, Jenő (Bubi) Beamter, Lajos Martiny, Mihály Tabányi, Jenő Orlay (Chappy) and several others resumed playing American-style jazz and jazz-influenced dance music in bars and nightclubs.Footnote 98

While clubs were watched closely, music halls were not, and thus they provided spaces for both politically and sexually explicit humour. The productions were targeted primarily at a Hungarian audience – there was hardly any chance to develop international tourism in Budapest at the time due to limited transportation options and government bureaucracy,Footnote 99 not to mention that the city was in ruins.

Aside from the many theatre artists who were killed, the profession lost others who either did not return to Hungary at the end of the war or left the country before 1949. These included composer Alfréd Márkus, comedian László Békeffi, acrobatic dance groups Trio Mexicanos and Trio Rudas and operetta stars Oszkár Dénes and Rózsi Bársony. The circle of employable artists was narrowed even further to only those approved by the regulatory committees (igazolóbizottság), which scrutinised the political past and attitudes of anyone who was publicly or privately employed.Footnote 100

MAE tried to re-establish itself as a trade union in 1945, but the Council of Trade Unions rejected its application.Footnote 101 Newly established trade unions functioned as tools of the communist takeover in every sector, and their creation made them easy to fill with the politically trusted as well as to discredit and replace older organisations.Footnote 102 MAE members were forced to join the new trade union by making membership a condition of performing in public from May 1947. Nevertheless, the fact that warnings to this effect were printed again and again and even appeared a year later in the professional journal Artisták Lapja suggests that in practice the requirement was frequently ignored. Eliminating the networks of theatre and music hall agents also took some time after agencies were taken over by trade unions. Professional artists formed a narrow strand of society that existed through interpersonal networks, which were difficult to control from the outside. Economic interests became stronger than professional solidarity: artists began informing on each other to lessen the competition.Footnote 103 MAE was disbanded in 1948, and the transition to Stalinism accelerated.

A press campaign against music halls began that harshly criticised the shows as being harmful and pornographic. Music halls were targeted because they were still privately managed and carried low cultural prestige. The threatening tone of journalists and the clear political messages toward music halls were new items in theatre magazines. For example, István Fejér wrote in the theatre magazine Színház és Mozi (Theatre and Cinema):

Theatre managers, music halls, provincial companies, nightclubs and even provincial and Budapest amateurs produce operettas, comedies and farces from the storage closet of the past, counting on the working masses’ desire for pleasantry. … Lies, intended reactionism, smokescreen, dulling people and destroying their taste. Mental fascism. This characterises that dangerous toxin which poisoned our people for decades and which we still wrongfully overlook and tolerate on the stages of the people’s democracy both in Budapest and in the countryside.Footnote 104

He thus removed all forms of boulevard theatre from the future of Hungarian theatre. The Kamara Varieté (Chamber Music Hall) was even accused of being a brothel where shows were only a side hustle. This was despite the fact that it was a theatre with a stage and about 150 seats arranged in rows. Aside from the critical crossfire targeting the shows, managers were often personally attacked in the press, including the formerly politically favoured Teddy Ehrenthal.Footnote 105

3.2 A Close Circle of Friends

The private sector had not completely disappeared by 1949. After the last wave of theatre nationalisation in July, the Municipal Grand Circus, the Royal, the Kamara Varieté and side shows still remained under private management. These venues were so far away from the political spotlight that the official Party proposal for a new theatre structure did not even mention them.Footnote 106

That situation, however, would soon change. The Municipal Council proposed the creation of a new municipal company, Fővárosi Népszórakoztató Intézmények (Municipal Institutions of People’s Entertainment, FŐNI). The goal of the new initiative was ‘to raise standards regarding cultural policy’.Footnote 107 The cadre of ambitious young people responsible for the proposal sought to take over the remaining parts of the entertainment sector.

One of the leading forces behind FŐNI was Béla Karády (1922–2016), the only child of a Jewish middle-class family. Bitten by the theatre bug as a child, from an early age he was writing reviews and playing ‘filmmaking’ with his friends. Karády had been a bocherFootnote 108 but gave up his rabbinical studies to study mathematics and art history at university. He began his theatre career as a prompter for the Jewish cultural association’s (OMIKE) theatre performances around 1939–40. In 1944, he was deported to the Mauthausen concentration camp. After his return to Budapest in 1946, he secured a job as an assistant director. His most important new professional relationship was with Margit Gáspár (1905–94),Footnote 109 a communist intellectual appointed to manage three municipalised theatres. She made Karády a stage director and head of public relations at Városi Színház, the largest theatre in the city. Karády joined the communist party in April 1947, presumably because it was required for his new position. When Gáspár took over the Operetta Theatre in 1949, she invited Karády to join her. Karády’s girlfriend was a soubrette at the Operetta, and if Karády took a high-level position there, it would have meant a conflict of interest. As he recalled,

So I said, she shall go to the Operetta and … we create FŐNI. It happened that Margit Gáspár was on the committee … that divided theatres and actors [among themselves]. … I asked, ‘So what happened to this person and that person?’ ‘Nothing. Wasn’t even mentioned.’ ‘Well, if that’s the case, let’s make something out of this.’ … Warm water was available in houses with central heating once a week. So we gathered on those days … in our house it was on Friday, in (János) Kublin’s house on Tuesday … and there we had baths. One of us was in the bathtub, the other sitting on the toilet, the third … FŐNI was born there.Footnote 110

Several reasons existed for establishing FŐNI. Under the state-socialist system, the only legal way of performing was as a member of a company – FŐNI provided job opportunities for actors. Perhaps the most significant reason, though, was Karády’s own ambition. When Gáspár took over the Operetta Theatre, Karády contacted his superior, Gábor Goda, the cultural councillor on the Municipal Council, to ask if the Royal was going ‘to be public property or left private’.Footnote 111 Karády had mastered the rhetoric of the Stalinist system and seeing the example of Gáspár, recognised an opportunity for himself.

Karády did not do this alone. He recruited friends and associates, none of whom had much professional theatre experience. For example, his friend János Kublin (1921–2001) was working for a film distribution company when the departing financial director of the Városi Színház recommended him as his replacement.Footnote 112 Kublin became the financial manager for FŐNI and brought his former classmate Egon Lázár (1921–2018) on board as an advisor.Footnote 113 Lázár recalled,

Kublin knew … nothing about financial leadership; he had a good sense of things but no knowledge. And I was home following imprisonment and he knew that I was working as … an officer sending out past due notices at the Európa Publishing House. … Kublin was in deep [distress] at the theatre and said to me, ‘You’re a bookkeeper. Come help me; you will be my acting manager.’ Fine. Why, if I could be a doctor and a reinforced concrete engineer for the Russians, why can’t I be a bookkeeper?Footnote 114

The fourth member of FŐNI’s leadership cadre was András Sólyom (1924–2012). Sólyom had organised occasional performances at the Városi Színház, where Karády befriended and subsequently employed him. Regarding his role in the company, Sólyom was referred to as the shammesFootnote 115 of Karády and Kublin (see Figure 7).

Figure 7 The FŐNI’s management on holiday at Lake Balaton, ca. 1950. Back row (l–r): András Sólyom, János Kublin, András Erős. Front row: Juci Hódossy (actor, Karády’s girlfriend), Béla Karády, Mária Medveczky (Kublin’s wife) and Mrs Erős. Egon Lázár, who took the photo, is not included.

The production side of the FŐNI team was recruited from another circle of Karády’s friends: established theatre professionals for whom the new system did not offer any work. Among them was Ernő Szabolcs, the sixty-two-year-old co-director of the 1925 show Halló, Amerika! The now doyen of operetta directors was subordinated to the twenty-seven-year-old newcomer Karády. Karády knew Imre Vogel, designer at the former Moulin Rouge, from the Royal and invited him to be part of FŐNI. Through Vogel, operetta composer Szabolcs Fényes joined the cadre. Even though Fényes was persona non grata (he was manager of the Operetta Theatre until 1949), Goda recognised his former tennis partner and offered him the position of FŐNI’s musical director.Footnote 116

Karády and his friends knew that they had to be acknowledged by the Party, but none of them had the personal prestige to make this happen. Furthermore, they had gathered around them discards from the private system, which did not help. Karády recalled,

We needed the first man, one who maintains a good relationship with the Party. That’s how (Endre) Székely came into the picture. … Even though I was a Party member, I did not have a good relationship with the Party and neither did Kublin. His brother recently emigrated to Switzerland, and I … [was told] that a communist cannot live in concubinage; so we needed someone acceptable for the Party and this is … where ‘Csúcsos’ (Tapered) came from. … The fact that he was a composer was a plus.Footnote 117

‘Tapered’ was the nickname of composer Endre Székely (1912–89), who became the official general manager of FŐNI on the recommendation of Gáspár and her best friend, the sister of the Minister for People’s Education. Székely’s position was only titular, however: Karády and Kublin led FŐNI. After taking the job, Székely almost immediately left for a five-month ideological course and hardly involved himself in FŐNI affairs.Footnote 118

The cadre was able to commandeer a major part of the entertainment sector thanks to personal relationships, professional networks and political alignments. Before 1945, neither Karády nor any of his friends could have managed a single theatre due to a lack of capital. Their limited professional experience would have made them ineligible for any leadership position. But because of the aggressive political transformation of cultural life, Karády, at age 27, was leading five theatres at the same time.

The main reason FŐNI could exist was that the political leadership did not have any plans for stage entertainment. This very mixed, low-prestige form of popular entertainment did not pose any threat to prominent theatre makers. The new enterprise was a low-level initiative in the sense that the Party leadership did not mandate its existence and that it did not copy an existing Soviet institution or structure, something that was expected in every field, whether it made sense or not. The Stalinist state accepted what Karády and his friends proposed since they had the support of people like Gábor Goda and Margit Gáspár.

On 8 October 1949, the police withdrew the licences of Royal Revű Varieté and Kamara Varieté and gave them to the Municipal Council, after which they became part of FŐNI. Karády recalled,

My Liebling was the Royal Revue Theatre … [my girlfriend] performed a couple of times under Teddy Ehrenthal … so I knew my way around there. … We had to nationalise. The process was that the state sent an excise officer [to each theatre] with a paper explaining what was happening. So each of us took this paper to a different place. I went to the Royal. We knocked on the door … [and] handed Teddy Ehrenthal the paper about us nationalising the theatre. We had two things to ask for: the key to the safe and the keys to the car. He had a black Mercedes. … He gave us [the keys] without a word. So the nationalisation was done.Footnote 119

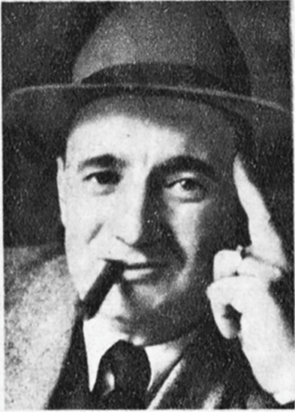

Ehrenthal, who acquired the theatre’s management from the Soviets, feeling political pressure, did not attempt to resist. He performed the ritual of self-criticism and used communist speech patterns to express his loyalty to the State (see Figures 8 and 9). He tried to negotiate with authorities to keep the management of the Moulin Rouge but did not succeed.Footnote 120 When he lost the Royal, he complained to the Municipal Council, but they did not even find his letter ‘worthy of reflection’.Footnote 121 Ehrenthal was only a placeholder; nobody dealt with him long-term. What happened to him before his death in 1958 remains unknown.

Figure 8 Teddy Ehrenthal in 1945. Színház, 14 November 1945, p. 15.

Figure 9 Teddy Ehrenthal in 1949. BÚÉK 1949, p. 3.

On 15 October 1949, all the remaining privately managed entertainment venues in Budapest were subordinated to FŐNI. The company was responsible for a wide range of genres from opera (in Városi Színház) to circus shows in five venues and two open-air stages.

The transformation of the entertainment sphere also brought about changes in terminology. Such an attempt was not without precedent; for example, in December 1941, dance hosts employed by the clubs (parkett-táncos) were renamed körtáncos (round dancers). A decade later, while varieté and revű were already fluid terms, along with others like vegyesműsor (mixed show), which all described the same thing, a new one was quietly being introduced: esztrád. While revű was discarded on political grounds, esztrád was a safe word in the sense that it was borrowed from Russian and became increasingly accepted after the Театр Эстрады (Estrada Theatre) opened in Moscow in 1954.Footnote 122 Since the image of showgirls was the polar opposite of new images of the working woman and mother, the word görl disappeared from public discourse for the next ten to fifteen years, although it still appeared in internal documents.

3.3 Show Business in the State-Socialist Theatre System

In 1950, a new state theatre structure was established on the Soviet model.Footnote 123 Ilus Vay, a comic actress, described the differences between the two systems:

Previously, a theatre was managed by three people: the manager, the secretary and a (female) secretary who did the administration, calculated and paid wages, distributed tickets and before she let issues go to the management, personally filtered and evaluated them. Now suddenly a party secretary was necessary, along with a trade union deputy, an arranger of membership stamps and other very important persons under God knows what titles.Footnote 124

The primary task of the management and the creative team was now to serve the political interests of their superiors. If they did not comply, they were quickly let go. Such demands appeared in every segment of cultural life.Footnote 125 The most successful theatre leaders of the period (Tamás Major at the National Theatre and Margit Gáspár at the Operetta Theatre) could sometimes resist the mandates through their political prestige, but they were exceptions.

The state theatre system meant that the Ministry of People’s Education now determined the number and profile of theatres.Footnote 126 The Minister directly appointed the theatre managers, who with resident dramaturgs, planned their seasons, which then had to be submitted to and approved by the Theatre Department of the Ministry. The manager had the right to select his creative team and artists; however, matters of hiring and firing also had to be approved by the Ministry. Artists could only be contracted for an entire season; if a role could not be cast in-house, the management could hire someone from another theatre, but only with the Ministry’s approval. Each manager had to hold weekly staff meetings and send minutes to the Ministry.

FŐNI theatres were reorganised according to this new structure, though many of the new positions did not make sense with their types of offerings. Positions such as dramaturg, writer or even director were not sharply defined (or even existed!) in the entertainment sphere before 1949. So much so that Vilmos Tarján, a gossip columnist – and manager of the Royal Orfeum from 1924 to 1926 – joked about it earlier:

In many ways, FŐNI was unique. While theoretically every theatre was equal and had the same cultural (political) worth, this was far from reality. The sharp distinction between venues geared toward entertainment and those that were not, remained and in fact widened. FŐNI was not a member of the new professional organisation, Magyar Színház- és Filmművészeti Szövetség (Hungarian Theatre- and Film Association), and the Ministry did nothing to help change this.Footnote 128 Twice the Ministry gave bonuses to the employees of state theatres, but not to those of FŐNI. FŐNI was the only company to control multiple theatres; the rest reported individually to the Ministry of People’s Education. Unlike those theatres, FŐNI was profit oriented. Its unified budget allowed for some financial flexibility within the structure. When they were under the private system, managers of FŐNI theatres had control over choosing productions and performers, now their roles were merely administrative. Every significant decision was made or ratified by FŐNI’s Central Management – Karády and Kublin.Footnote 129 The two of them intended to keep as much power as possible to themselves and make their theatre managers de facto secretaries. As Karády recalled,

I decided that Tom, Dick and Harry will perform in the show, but the contract was written and negotiated by the … theatre manager. [It] became valid only when the Central Management – namely me – signed it. … I think it was clear that the Central Management had the power, and they only did minor tasks.Footnote 130

The collapse of this new system was only a matter of time. In fact, Karády and Kublin were only able to keep their positions for one season. By June 1950, FŐNI had become entangled in a complex web of conflicts, and its position was weakened both externally and internally.Footnote 131 On one hand, managers were trying to become more independent and secure actual managerial rights for themselves. On the other, the attitude of the Municipal Council had changed. Gábor Goda, the ‘patron’ of FŐNI, resigned to focus on his new career as a novelist. His successor had a radically different opinion on how shows were supposed to look. The result of this two-front war was that Karády and his colleagues were officially sacked at the season-closing company meeting on 22 June 1950.Footnote 132

FŐNI, though, continued. A certain Mrs Sásdi,Footnote 133 a cleaning lady at the Grand Hotel, was named general manager. This was in line with the impractical ideological practice of appointing physical workers to lead state companies. Many of these ‘worker managers’ never had been in an actual factory or business, and they often knew nothing about the profession they were supposed to lead.Footnote 134 Mrs Sásdi fit this profile, for she was ignorant about theatre. Though she and her new management team were not going to be attacked politically, they had a major problem: performers and other artists were resisting the new aggressively politicised leadership style. This led to contradictory instructions and increasingly unclear job expectations. Within a few months, the artistic work had become extremely chaotic, which resulted in a widespread institutional crisis.

The weekly meetings of almost every sector of the Municipal Music Hall were devoted to complaining. The orchestra straight-out criticised the leadership for ignoring the fundamental aspects of putting on a show: ‘[The composer] Szabolcs Fényes is not involved in pre-production, even though the basis of the revue is the music. There are two directors, but there is still no finale as of today. … The audience only notices that the show is over when the orchestra leaves’.Footnote 135 Then, at an actors’ meeting, Gertrúd Romváry pointed out the political pressure and the demoralising atmosphere:

[She] asked many times: Who is the artistic director here? Who is the manager? There are eight directors here, and staging instructions come in the form of orders, not like they are discussed with the actor. What kind of order is this, she once asked. An order from above, she was told, so she cannot criticise it because it comes from above her.Footnote 136

News of these problems reached the Ministry by spring 1951, for in April of that year FŐNI was disbanded. Only two years after the theatre industry’s municipalisation–nationalisation, its operations had to be revised. FŐNI venues remained in municipal ownership, but now as independent theatres.

At the Municipal Music Hall, the Ministry of People’s Education appointed István Fejér as manager. Fejér, a former journalist for the weekly theatre magazine Színház és Mozi (Theatre and Cinema), rebranded the theatre as Fővárosi Víg Színház (Municipal Gaiety Theatre) and began a Ministry-approved experiment with revues. The venture failed, and after just one season, the theatre changed its focus to operettas.

Public demand for a music hall (even if it didn’t offer revues) was such that plans for a new venue were announced in May 1952. The former Kamara Cinema, built on the site of a hotel swimming pool in the city centre, was to be refurbished for this purpose. The new venue was to be called Fővárosi Nagy Varieté (Municipal Grand Music Hall), even though it was smaller than the Royal. While the Royal was being renovated to mount operettas, the building’s condition was discovered to be so bad that it could not be saved, and it was demolished in 1953. So, rather than the Fővárosi Nagy Varieté, the Fővárosi Víg Színház moved into the former cinema, and, yet again, operetta superseded music hall.

The second reorganisation of state theatres within five years took place in 1954. The Fővárosi Víg Színház lost its independence and was subordinated to the Operetta Theatre.Footnote 137 Since Fővárosi Nagy Varieté did not materialise, the Országos Cirkusz Vállalat (National Circus Company), opened the small Budapest Varieté (Budapest Music Hall) on the edge of the VIII district, far from the historical theatre district. Béla Karády was its first manager, who intended to create a ‘small Royal’; but its budget and infrastructure made it impractical for revues, and it closed in 1960.

3.4 Nationalising Nightlife

The nationalisation of clubs and the catering trade happened in waves, similar to that of the theatres. Between 21 and 31 January 1949, thirty-eight bars and coffee houses were nationalised, fourteen of which immediately closed. In some cases, drastic design changes were made, such as the removal of the chinoiserie interior at the former Sanghay Club. By the end of the year, another ninety-one venues had been nationalised and subordinated to the newly created Éttermi és Büfé Vállalat (Restaurant and Buffet Company). The process was quick, as an anonymous former employee recalled:

The owner did not come in for the second day in a row. We knew that he had been well-informed through his connections. … It was around 5 p.m. when we heard that the nationalising committee [was coming]. By that time nobody was working; the guests were sent away … only a curious couple remained. Three of us were sitting in the office, the cashier, the bookkeeper and me, who was in charge of the finances. … As ‘the boss’s men’, we were quite concerned. Three men came up – they were at least as anxious as we were – two of them from the trade union and the third who we recognised as the head waiter from the Abbázia [a coffee house]. ‘We are nationalising the shop in the name of the people’, said one of them. … They reported on the act of nationalisation, collected money and valuables from the cash desk, regardless of where they came from, what they were for or who owned them, and handed them to the appointed company leader. … One of the trade union members vigorously warned us: ‘From this moment, the former owner is not allowed to enter. Everything here has been seized in the name of the people, for he obtained this [capital] through the exploitation of workers. None of you should attempt to give him or smuggle out any items, objects or valuables because we will punish such actions according to the law. For now, you can continue working and then we’ll see’.Footnote 138

Starting in 1951, control was decentralised and district companies managed the venues. The secret police kept a close eye on the Moulin Rouge and other clubs.Footnote 139 Foreigners were regulars at these places because their offerings were more accessible to them than the experimental revues, which were mainly in Hungarian. (Also, diplomatic immunity meant security from the police.) Several Hungarian actresses found foreign suitors in the bars; the State secret police attempted to recruit these women and have them report on their boyfriends. Refusing the ‘offer’ had serious consequences, such as being banned from the stage and family members losing their jobs. Those who accepted were rewarded.Footnote 140

Controlling the content of performances in the clubs and coffee houses became another problem. Before 1949, such shows were organised by the management or through agents. After 1949, private individuals were forbidden to produce anything on stage.Footnote 141 Clubs depended on their clientele and to keep them, they sometimes ignored what was happening on stage. As one observer noted, ‘Most of the hostile remarks were not in the written text but in the (improvised) jokes of the actors, against which the manager of the venue did not do anything but was happy that there were two more laughs and that a certain part of the audience was enjoying itself’.Footnote 142

In 1953, the Municipal Council established the Budapest Műsoriroda (Budapest Production Office) to better control the club shows and their musicians. Soon it was reorganised as Népi- és Tánczenei Központ (Folk and Dance Music Centre) but managers complained that this centralised system was ineffective and expensive. Every musical programme had to be submitted to this body. Some Western European songs performed with Hungarian lyrics were generally included, though it was advised to have no more than two or three such songs out of a total of eight-to-ten pieces. Informants went from club to club, noting who played what.Footnote 143

Following a successful lobby after the 1956 Revolution, clubs were able to hire their own artists. The Moulin Rouge, renamed Budapest Kávéház (Budapest Coffee House), was the only major nightclub of the previous era to still produce shows, though hardly any information about them survives. Dance and musical acts dominated (one of the best bands in town was still playing there), and significantly fewer artists appeared on its stage than previously. Protectionism kept this number small.Footnote 144 Since the system of control was not prepared to handle non-theatrical productions, clubs maintained a bit of autonomy. These productions were not part of the socialist revue experiments; they were barely acknowledged and only rarely advertised in the papers.

4 The Socialist Revue Experiments

Even though revues were largely ignored under the new theatre system, the genre remained popular. Revues had to be legitimised in the new cultural context, which valued only their ‘educative’ features. Therefore, an approach to the genre needed to be found or created that would satisfy both politicians and audiences. Although entertainment was already nationalised once during the brief Soviet Republic of Hungary in 1919Footnote 145 and the Hungarian worker’s theatre movement in the 1930s produced leftist political shows, none of these precedents were known by those now in charge.Footnote 146

4.1 The Trade Union’s Alternative to Private Entertainment

The first revue experiment happened before the municipalisation of theatres. In June 1949, the Trade Union sponsored and produced a revue on the open-air stage at Angol Park (Amusement Park). Written by István Fejér, a journalist who was perhaps the loudest voice against private entertainment, Meserevű (Fairy Tale Revue) reflected his personal dictates. According to Fejér, a revue should be

written by writers who don’t see expressing the optimistic, cheerful message of the era as a burden. … [The revue] should not be a pulpit for political theorems … nor the messenger of the world view of the grand bourgeoisie. … It should be witty and fun and not merge humour with obscenity. At the same time, it should not be any less spectacular than the old revue. … It should not be written around the ‘star’ … the artist should serve the revue.Footnote 147

While the show’s book is lost, its overall plan is known: contrasting scenes depicting the ‘old times’ and the ‘present’ were alternated to convey the superiority of the present. Fejér reviewed his own show in a theatre magazine and chastised the production team for ignoring and removing its political messages.Footnote 148 Three months later, FŐNI was established, and Fejér’s experiments with revues ended.

4.2 FŐNI Revues