1 ‘Almost the Utmost Border of the Earth’

Introduction

By sheer coincidence I finished work on this Element at the same time as elections took place in the United Kingdom and France. The political campaigns highlighted similar issues: national sovereignty in relation to the European Union, and the threat to national identities supposedly caused by immigration. In Britain the debate extended to devolution – should Scotland and Wales become independent states? These discussions were divisive, and most were poorly informed, but they were by no means new. Some of the same themes have influenced accounts of European prehistory. That is why this Element was written.

Archaeologists have considered similar topics and expressed similar concerns. They treated Britain as self-contained and employed it as a laboratory for investigating island archaeology. In the same way there have been studies of the European mainland which extended no further than the Channel – British archaeology is used, if at all, as a source of methods and theories. This Element reflects on those relationships, but it is primarily a review of the insular sequence in relation to broad themes in Continental prehistory. It is addressed to readers who are unfamiliar with new work in this offshore island and may not be persuaded of its relevance to European archaeology. It focuses on three subjects: the changing relationship between different parts of Britain and its neighbours; communications along and across the seaways that separate the island from the mainland; and the extent to which prehistoric Britain forms a coherent unit in scholarly research.

It is written for a series published in English and, where possible, the same applies to the sources cited in the bibliography. It is also subject to a strict word limit and for that reason the references include general syntheses or edited collections as well as individual papers. For a wider range of sources (in several languages) the reader is referred to two related publications: The Later Prehistory of Northwest Europe (Bradley, Haselgrove, Vander Linden & Webley Reference Bradley, Haselgrove, Webley and Vander Linden2016) and The Prehistory of Britain and Ireland (Bradley Reference Bradley2019).

Island Identities

Definitions matter. The title of this Element refers to insularity, identity, and prehistory. Why were these terms chosen, and how should they be understood?

Insularity has a double meaning. It acknowledges that Britain is an island, but it can also indicate a rejection of the wider world. During the postglacial period rising seas separated Britain from the Continent, but in the past its inhabitants either emphasised their separation or they chose to overcome it. That explains the reference to identities. The notion of prehistory refers to the time when understanding of the past depends on material remains. Written accounts are rare and problematic. Several refer to the pre-Roman Iron Age and present an outsider’s view of Britain. These sources were seldom based on first-hand observation and included statements which were demonstrably wrong.

Two accounts of insular geography illustrate these points. One was written by the Greek geographer Strabo just before the Roman invasion in the first century ad. The other text was composed by the British monk Gildas 500 years later. It was composed after the imperial administration had collapsed, and the island no longer formed part of a larger European community.

According to Strabo:

Pretannike [Britain] is in the shape of a triangle … There are four crossings that used to go to the island from the continent … Most of the land is flat and thickly wooded (although many places have hillocks), and it produces grain, cattle, gold, silver, and iron … [Some of the inhabitants] who have abundant milk do not make cheese because of their inexperience, and they have no experience of gardening or other agricultural matters … . The air is rainy rather than snowy, and when it is clear it is foggy for long periods.

As an inhabitant of the island, Gildas emphasised its inaccessibility:

Britain, situated on almost the utmost border of the earth … stretches out from the south-west towards the north pole … . It is surrounded by the ocean, which forms winding bays, and is strongly defended by this ample and … impassable barrier save on the south side where the narrow sea affords a passage to Gaul. It is enriched by the mouths of two noble rivers, the Thames, and the Severn.

In their different ways Strabo and Gildas were making the same point. They epitomised a perspective that has influenced approaches to the past. In Strabo’s Geography, the island is cut off from other parts of Europe. Its climate is harsh, and its inhabitants are unsophisticated. They share very little with people living on the European mainland. Someone raised in the Mediterranean would not have found Britain a congenial environment. Gildas takes a different line. The island has natural defences allowing its occupants to maintain their independence even after the collapse of Roman rule. Its isolation and independence constitute Brexit in reverse – the British had not withdrawn from membership of a larger Europe; instead, the Roman army had departed, and the Empire was in decline.

Some of the same assumptions influenced the work of twentieth-century prehistorians. Because Britain was located on the outer edge of Europe, they considered that its inhabitants would take a long time to become aware of developments on the Continent. The adoption of new practices, technologies, and ideas was significantly delayed. That made it difficult for archaeologists to synchronise developments on the European mainland with those on this offshore island. Before the development of radiocarbon, prehistoric chronologies depended on cross-dating. Such equations became increasingly tenuous where they extended over long distances.

These problems are illustrated by an article published long ago. One of the first researchers to study European chronology was the Swedish polymath, Montelius. By investigating the associations between distinctive artefacts in burials and hoards he was able to consider the relationship between prehistoric sequences in different countries. Absolute dates were established by links with the Mediterranean, the Aegean, and Egypt. He published a new account of Bronze Age Britain, dividing the insular sequence into five phases and proposing a fresh chronology (Montelius Reference Montelius1908). His findings were immediately rejected by insular scholars who preferred dates which were later than his estimates by as many as seven centuries. Today radiocarbon suggests that Montelius was largely correct. In fact, his projections were astray by just fifty to a hundred years.

A second assumption was that when significant changes did occur in Britain they followed – and in most cases were inspired by – earlier developments on the mainland. The best example of this approach is provided by a well-known monument. The building of Stonehenge was originally attributed to foreign contacts. It was assigned to the Early Bronze Age because the main setting of monoliths was compared with Mycenaean architecture. The carvings of metal axes and daggers on their surfaces were like examples in southern Europe (Atkinson Reference Atkinson1956). The comparison is no longer credible as radiocarbon dating shows that Stonehenge was erected hundreds of years before any of its supposed prototypes.

The argument has an important corollary. Because Britain was so remote, it seemed unlikely that developments in an offshore island would have had a wider impact. Insular prehistorians were aware of Continental research, but for Childe writing his account of European prehistory in 1925 and Hawkes who published his version fifteen years later (Hawkes Reference Hawkes1940) ideas moved in only two directions – towards the north and west. For these scholars, and for most of their contemporaries, virtually any new development in pre-Roman Britain was introduced by settlers from overseas. The preferred model was described as the ‘invasion hypothesis’. The empirical basis for some of these interpretations was tenuous, and in 1966 it was reviewed in an influential article by Clark (see also Hofmann et al. Reference Hofmann, Frieman and Furholt2024).

There have been several developments since then. The first was a decline in foreign language teaching in Britain. Insular prehistorians became less familiar with Continental publications. They did not read as widely as their predecessors and as a result, their own work carried less authority overseas. At the same time American ‘processual archaeology’ influenced scholars in Britain and Scandinavia but had a limited impact elsewhere. At its most doctrinaire it erected an intellectual barrier between British researchers and their colleagues in other parts of Europe. Proponents of the New Archaeology argued that many different processes could lead to changes in ancient society. Adaptation was at least as relevant as migration, and interpretations of the past were increasingly influenced by a kind of functionalist anthropology which has since been abandoned. Even when theoretical fashions changed and ‘post-processual’ archaeology took its place, the emphasis on local developments remained.

Again, the archaeology of Stonehenge is particularly informative. Where previous scholars had looked for distant parallels, Renfrew (Reference Renfrew and Renfrew1973) argued that the setting of monoliths was the culmination of a process of monument construction within southern England which had already extended for a thousand years. There have been revisions to his chronology, and some developments turn out to have been unexpectedly abrupt. Even so, recent accounts identify the prototypes for this extraordinary building among the timber circles already present in Britain (Gibson Reference Gibson2005). At the same time, they emphasise the striking contrast between insular architecture and structures of the same date on the Continent.

The notion of British separateness was illustrated by other studies. When Clark (Reference Clark1966) questioned the invasion hypothesis, he contrasted uncritical interpretations with two cases in which settlement from the mainland was generally accepted. One was the arrival of the first farmers during the Neolithic period, and the other was a period of colonisation by people who used Bell Beakers and metalwork. Even these interpretations have since been questioned. Perhaps domesticated resources were adopted by hunter-gatherers from their neighbours on the Continent. That was the argument of a book published by Thomas (Thomas Reference Thomas2013). Similarly, Burgess and Shennan (Reference Burgess, Shennan, Burgess and Miket1976) were among the first to suggest that Beakers and their associations might have been associated with special practices or beliefs by the local population – these artefacts need not have expressed ethnic identities. For a while those arguments presented plausible alternatives to the established orthodoxies, and it seemed as if connections between the island and the mainland might have been overemphasised.

Recent Developments

Now the situation is changing. At a time when British separateness has become a dogma of right-wing politics, there are new ways of investigating this issue in the past. What are the best methods of documenting the movement of people and artefacts (Outram & Bogaard Reference Outram and Bogaard2019)? And how well do traditional chronologies stand up to new methods of dating?

The study of stable isotopes preserved in human and animal bones has documented unexpected levels of mobility in the pattern of settlement; these methods show that people might have lived in more than one region during their lives. Only occasionally can the results of this research distinguish between individuals who travelled between separate parts of the island and first-generation immigrants from the Continent, but some candidates have been identified. Isotopic archaeology is limited to individual biographies, but studies of ancient DNA investigate the ancestry of whole populations (Kristiansen Reference Kristiansen2022). The results of this work have been even more dramatic and support ideas about prehistoric settlement from overseas that had become increasingly unfashionable. It is not clear how many immigrants were involved, and the same method records the genetic contribution of the indigenous population. The only caveat is that cremation burials cannot be studied by this technique.

New developments in radiocarbon dating play an equally important role. Individual determinations are more precise, and in ideal cases statistical procedures allow archaeologists to build fine-grained chronologies (Hamilton, Haselgrove & Gosden Reference Hamilton, Haselgrove and Gosden2015; Griffiths et al. Reference Griffiths, Carlin and Thomas2023). They permit more exact comparisons between British and Continental sequences. Another kind of study employs frequency distributions of radiocarbon dates to infer changing population levels and the impact of people on the environment (Shennan Reference Shennan2013; Woodbridge et al. Reference Woodbridge, Fyfe and Roberts2014). Such work takes no account of conventional cultural divisions.

Conventional methods of investigating and dating the movement of people and artefacts may be reaching their limits. The classification and sequencing of artefacts do not provide such precise results as more recent approaches. Time-honoured ways of defining cultural traditions and arranging them in order are not sufficiently subtle, and in some instances, their results have even been misleading. The notion of British separateness may not stand up to scrutiny. Traditional studies have their merits, but mobility and long-distance contacts can be investigated in other ways.

If archaeological science has an important contribution to make, equally significant information comes from a different source. Over the last thirty years, the number of field projects has increased in Britain and neighbouring parts of Europe (Bradley, Haselgrove, Vander Linden & Webley Reference Bradley, Haselgrove, Webley and Vander Linden2016). Previous generations of researchers were obliged to study grave goods, hoards, and single finds because most investigations of settlements and landscapes were conducted on a small scale. That is no longer true, and more extensive projects take place in advance of commercial development. Methods vary between different parts of Europe – and even between regions of Britain – but the new information presents a challenge. The sheer extent of recent excavations permits a more thematic approach to prehistoric societies in Britain and on the Continent. It places a new emphasis on settlements, cemeteries and monuments where earlier generations were obliged to consider regional traditions through the medium of portable artefacts. This Element reflects that change of emphasis and studies of pottery and metalwork play a smaller role.

New Perspectives

How can archaeologists investigate the changing identities of Britain and its inhabitants during the prehistoric period? The present account has two starting points. One is to reconsider the relationship between different parts of this island and all its closest neighbours. Another approach is to question the idea of Britain as a geographical unit during the pre-Roman era.

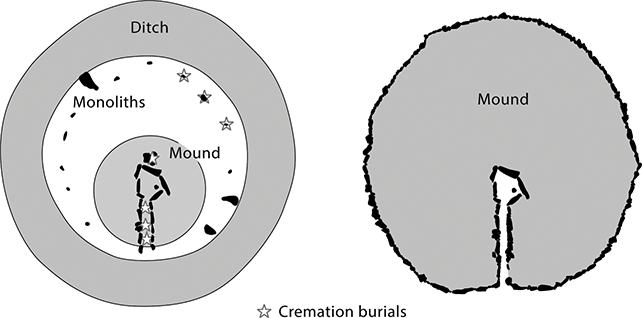

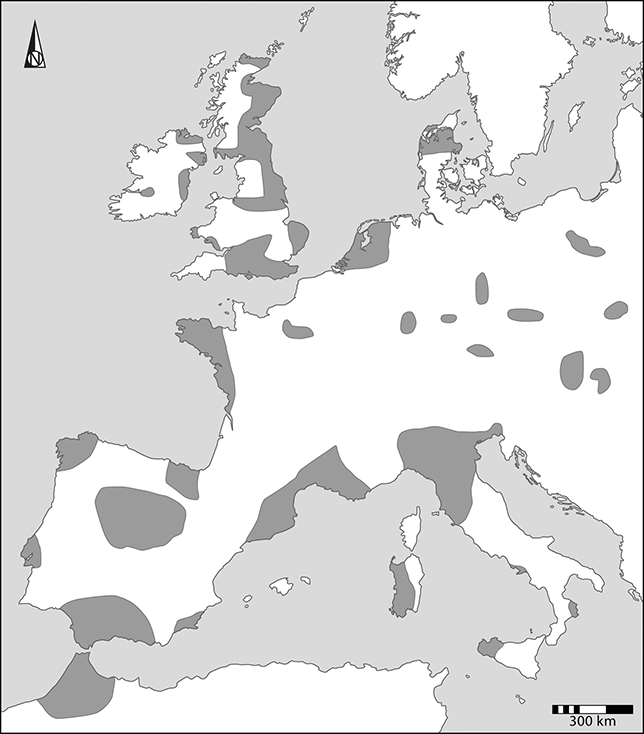

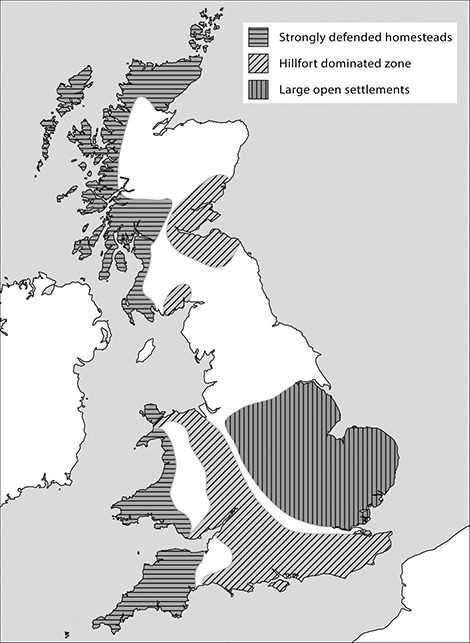

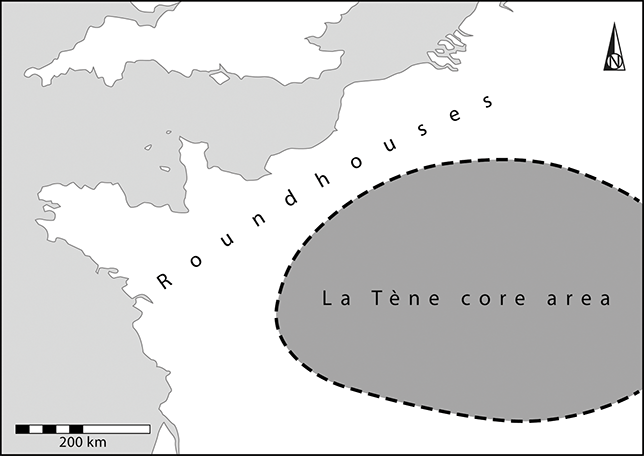

Information from Ireland is commonly compared with that from Britain (Bradley Reference Bradley2019), but this account takes a different course. It considers Ireland, France, Belgium, north Germany, and the Low Countries, parts of which are within 500 km of the British coast (Figure 1). At times it extends even further – down the Atlantic as far as the Iberian Peninsula, and along the North Sea into South Scandinavia. But there are obvious difficulties in treating these areas on equal terms – contemporary politics carry too much weight. For instance, it has been common to treat Britain and Ireland as the ‘British’ Isles. This is because both islands were once ruled from London. Geographically, they are close together – the north of Ireland is visible from Scotland, and they are separated by a short sea crossing. But the same applies to the relationship between southeast England and northern France, yet their archaeological records are less often compared; important exceptions are Bourgeois & Talon (Reference Bourgeois, Talon and Clark2009) and Lehoërff & Talon (Reference Lehoërff and Talon2017).

Figure 1 The island in relation to its neighbours. The shaded area shows regions within 500 km of the British coast

Any account of the relations between Britain and its neighbours must focus on the seaways that connect them. In the past, they were contested spaces whose very names were revealing: the ’English’ Channel, the ‘Irish’ Sea, and the North Sea which was once called the ‘German’ Ocean. Landing places have been identified from concentrations of prehistoric remains associated with sheltered harbours. Computer simulations have played a part and so have practical experiments. Among the main considerations are the visibility of landmarks and seamarks, currents, and prevailing winds (Van de Noort Reference Van de Noort2011). Although voyages were possible between France and southeast England, and between southwest Scotland and Ireland, others might have followed the shoreline until they reached the safest crossings. People travelled between different parts of Britain but need not have been aware that it was an island before it was circumnavigated by Pytheas during the fourth century bc (Cunliffe Reference Cunliffe2001a).

Lowland England was crossed by navigable rivers, but further to the north areas of high ground separated the east coast from the western seaboard. There were comparatively few ways between them (Figure 2; Fox Reference Fox1932). Not surprisingly, the archaeologies of the North Sea and the Atlantic show some contrasts and for that reason each can be considered on its own terms. To some extent the same applies to the Channel. Britain was not a single entity during the prehistoric period.

Figure 2 Prehistoric geography according to Fox (Reference Fox1932), emphasising upland areas and land routes between the North Sea and the Irish Sea

The Organisation of the Text

In the light of these observations, this account is organised in two ways. Strabo described the shape of Britain as a triangle. It was bounded by seaways that met at all three of its points: Cornwall to the southwest; Kent to the southeast; and Caithness to the north. Beyond them there were offshore islands, the most significant of which were the Hebrides, Orkney, and Shetland. Each sea faced a different landmass, although the distances between them were not the same. The Channel linked southern England to France and Belgium (Bourgeois & Talon Reference Bourgeois, Talon and Clark2009; Lehöerff, Bourgeois, Clark & Talon 2012). The North Sea provided connections with Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands; still further away were Denmark and Sweden (Van de Noort Reference Van de Noort2011). The narrowest divisions were across the Channel where sections of the shoreline were intervisible. The Atlantic joined Britain to Ireland and western France and, at a greater distance, to the Iberian Peninsula (Henderson Reference Henderson2007; Cunliffe 2010b; Moore & Armada Reference Moore and Armada2011). It also connected northern Britain, Ireland, and Scandinavia. On the other hand, the sheer length of the British coast, combined with the rugged interior from northern England to the Scottish Highlands, might have meant that there were few contacts between communities living along different arms of that triangle. Lowland regions, however, were densely settled, and here journeys along rivers or overland were easier.

One starting point is to eschew the distinction prehistorians have made between the British and Continental landmasses. Instead, there will be more emphasis on the different seas that connected this island to other parts of Europe. All Britain’s neighbours will be treated on equal terms, without privileging relationships across the Irish Sea or emphasising the special importance of the Channel; both have been common in recent scholarship. That is not to deny that some connections were more important than others, nor does it follow that close relationships existed simply because different regions could be reached from one another. Some links were thought to be important in the past, and others were rejected.

It is vital to consider each axis, contrasting developments along the North Sea with those along the Irish Sea, and comparing them with the archaeology of the Channel coast. In doing so, both sides of water must be given due weight. There were times in which communities do seem to have been closely linked. They practised a similar lifestyle. During other periods there were no such parallels, and it is important to decide whether the contrasts between them were meant to express different identities or whether they reflected phases in which there were fewer contacts.

This account falls into three sections based on absolute dates rather than technology. It begins at 4000 bc when the island of Britain was already cut off from the Continent, and the first section extends from the initial agricultural settlement to the building of extraordinary monuments like Stonehenge. By the later third millennium bc, insular ways of life were influenced by developments associated with the use of Bell Beaker ceramics and metallurgy. The second section acknowledges this development and considers the period in which new practices, new burial rites, and the movement of metals were shared across Britain and northwest Europe. It extends down to 1200 bc, by which time settlement patterns had changed in many regions. From then on, long-distance trade and conspicuous consumption played a more obvious part. There were episodes of expansion and contraction, but these developments continued largely unchecked until most of the regions considered here came into contact with the Roman Empire. Although many elements persisted afterwards, it is where this discussion will end.

2 Isolation and Inclusion (4000–2500 bc)

Again, definitions are important. In the past, isolation could be both physical and cultural, yet there was no necessary relationship between them. Britain was isolated from the mainland after sea levels rose during the postglacial period, but that did not mean the end of contacts between people in different regions. Their practices and beliefs need not have diverged significantly. Instead, the inhabitants of distant places could have emphasised their inclusion within a wider world. Both possibilities are illustrated by developments in the prehistoric period.

Other terms need equally careful handling. In this context, it is important to distinguish between ancestry and descent. Descent can be documented by the genetic evidence preserved in human bones, but ancestry is a cultural concept, governed by choice as well as parentage. Descent does not determine lifestyle, behaviour, or identity. These are choices made by living people. This distinction can be overlooked in exchanges between archaeologists and scientists (Booth Reference Booth2019). There are dangers in attempting to match ancient DNA with styles of pottery. The account begins by considering when Britain became an island.

An Initial Fragmentation (10,000–4000 bc)

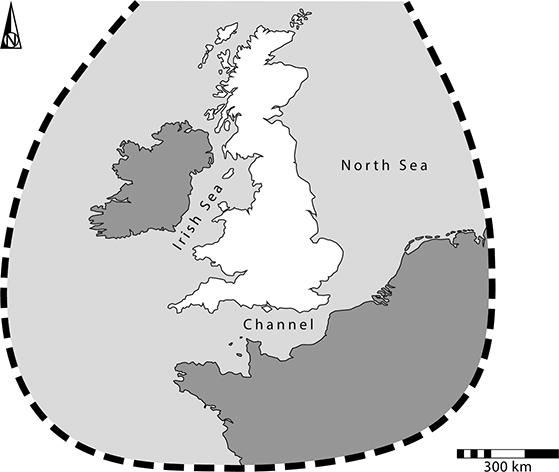

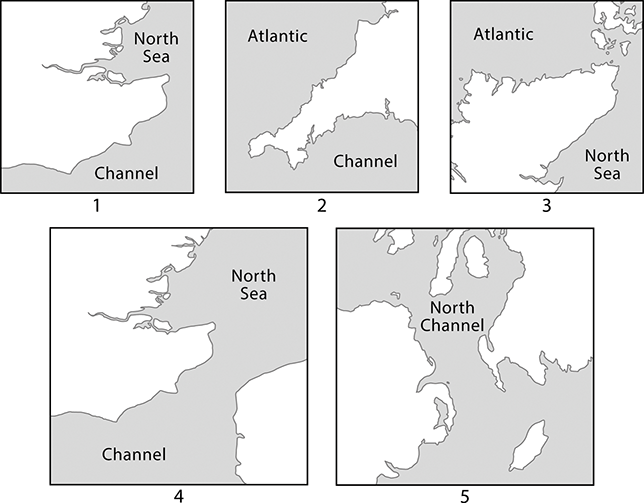

In 2021, an exhibition was held at the Dutch National Museum of Antiquities. It was called Doggerland: Lost World under the North Sea (Amkreutz & van der Vaart-Verschoof Reference Amkreutz and van der Vaart-Verschoof2022). The displays covered many topics, but their starting point was the extraordinary number of artefacts recovered by dredging the seabed between the Netherlands and Britain. These finds spanned an enormous period, from the Lower Palaeolithic to the Mesolithic phase. The latest dated from the sixth millennium bc when large areas of land had already been inundated and rising water separated northern France from southern England. Even the low island represented by the Dogger Bank eventually disappeared (Figure 3). Few Neolithic items have been found in the North Sea. The exceptions are fine stone axes which might have been deposited as offerings in places which had once been significant. Whether or not one accepts this interpretation, the contrast with the Mesolithic evidence is striking.

Figure 3 Britain before and after it became an island.

Until the North Sea basin flooded, what is now eastern England formed part of the European continent. In 1976, Jacobi observed that before the land bridge was severed the same material culture was employed across a considerable area. After it happened, new kinds of artefacts were used on what was now an island. They contrasted with those in mainland Europe. His case has been supported by subsequent writers; Ballin (Reference Ballin2016) provides a summary.

Similar developments happened on a smaller scale. To the west of Britain was Ireland, but it was separated from Scotland and Wales before it had any occupants and must have been settled by sea. That had already happened by 8000 bc. During an initial phase the inhabitants shared the same material culture as their neighbours, but this relationship had ended by 6000 bc. Otherwise, the last hunter-gatherers in Ireland became independent of their neighbours (Woodman Reference Woodman2015).

There were other contrasts. In two regions hunter-gatherers encountered farmers who were settling new land along the European coast. Towards the north, in the Netherlands, Germany and Denmark, both groups occupied adjacent areas and exchanged artefacts and resources for many years. Pottery was adopted by indigenous communities. It was not until 4000 bc that the new economy extended beyond the ‘agricultural frontier’. The reasons for this development are uncertain, but the outcome is unambiguous (Gron & Sørensen Reference Gron and Sørensen2018). Although wild resources were still exploited, stock raising and cereal cultivation extended into the Low Countries, north Germany, and South Scandinavia, the genetic makeup of the population changed (Allentoft et al. Reference Allentoft, Sikora and Fischer2024), and people adopted a new material culture.

The second area where agricultural settlement impinged on indigenous ways of life was northwest France, but here the relationship was expressed in a different way. The new settlers had a wider range of contacts – with Normandy and the Paris Basin to the east, and along the Atlantic coast to the south – but in this case, the most striking development was the first appearance of monuments (Scarre Reference Scarre2011). It is evidenced by decorated standing stones, cists, and megalithic tombs. It is impossible to tell whether they were erected by immigrants or by local communities, but they were established at the time of contacts between those groups.

Because Britain was accessible by sea from both areas these developments have been used as analogies for occupation of the island (Sheridan & Pétrequin Reference Sheridan and Pétrequin2014). Whatever the merits of more detailed versions, several points are generally accepted. In almost every area people introduced domesticated plants and animals. They also adopted material culture like that used on the Continent. At the same time, they erected structures of the kinds built in mainland Europe. The evidence of ancient DNA provides compelling evidence of an immigrant population (Brace et al. Reference Brace, Dickmann and Booth2019). It is obvious that British isolation was finally at an end.

Many questions remain. Was Britain entirely isolated until this phase? Did the settlement of early farmers begin in only one region, and was it restricted to a single episode of contact? Were there phases of immigration from different parts of the mainland, and how long were relations maintained with Continental communities? Such issues are difficult to resolve, but each of them touches on the relationship between insularity and identity.

Radiocarbon dates suggest that during the fifth millennium bc the native population was small (Conneller Reference Conneller2022). There is little to indicate long-distance contacts after Britain was cut off by sea – the only direct evidence comes from artefacts of Continental types found at a few places in southern England (Lawrence et al. 2022). Unlike the situation in Northern Europe, the last Mesolithic sites rarely contain items associated with early farmers, nor do they provide evidence of monumental architecture. Microliths are rare in the early fourth millennium bc (Griffiths Reference Griffiths2014). Outside western Scotland (Mithen Reference Mithen2022) the period between about 4000 and 3500 bc marks a new beginning.

How did it happen? The evidence of ancient DNA can be interpreted in more than one way (Whittle, Pollard & Greaney Reference Whittle, Pollard and Greaney2023). So can the results of radiocarbon dating. There is no consensus, but the transition took a long while and the first developments began at different times in different regions. Taken together, they spanned almost 350 years (Whittle, Healy & Bayliss Reference Whittle, Healy and Bayliss2011, 866–71). Perhaps the people who came there used the shortest crossings between Britain and the mainland and then travelled inland from the coast. Otherwise, the dates suggest that they followed the North Sea rather than the Channel. There may have been another axis linking northwest France to southwest England.

It is important to consider styles of material culture, and the same applies to artefact distributions, but it is just as useful to study activities which were unlikely to express local distinctiveness. One of the most significant was flint mining since a series of specialised techniques developed in France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. They were concerned with safe methods of working underground and could only have developed by trial and error. They are evidenced in southern England at the beginning of the fourth millennium bc when there were particularly close connections across the Channel (Baczkowski Reference Baczkowski2014). Ceramic technology provides another source. Again, it was learnt by experience and for that reason it can be as informative as the styles of finished vessels. A study by Pioffet (Reference Pioffet2015) identifies different ways of making pots between the east and west coasts of Britain. Her analysis is particularly important as the same procedures were followed in neighbouring parts of the Continent: northern France and southern Belgium, in one case; and Normandy and Brittany, in the other. There were more distinctive developments in northeast Scotland.

An Initial Integration (4000–3600 bc)

Although such processes extended over a significant period, their most striking feature is that they ran in parallel between Northern Europe, Britain, and Ireland (Sheridan & Pétrequin Reference Sheridan and Pétrequin2014; Gron & Sørensen Reference Gron and Sørensen2018). Of course, there were local differences, but the resemblances between them outweigh any contrasts. Although these processes were associated with different styles of artefacts – in particular, axes, arrowheads, and pottery – other elements were widely shared. They included an initial emphasis on land clearance and a dispersed pattern of settlement. Cereals were represented from an early stage, but after that time there may have been greater mobility and more emphasis on livestock. Domesticated cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs were introduced to new regions. They must have been taken by boat to Britain, Ireland, and the Danish islands; the same applies to grain. Wild plants, on the other hand, remained important, and by this time hunting played a restricted role.

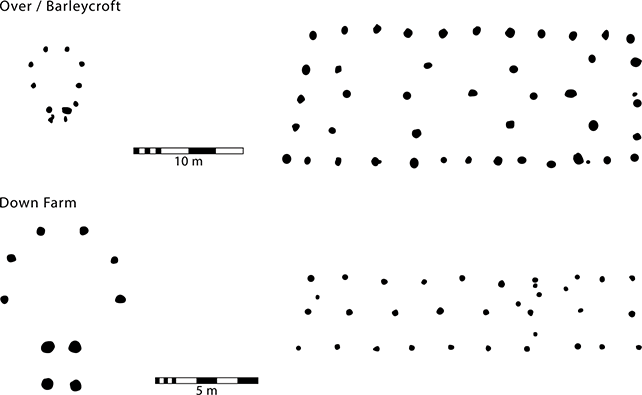

The surviving settlements have a limited distribution in space and time. The clearest evidence comes from Ireland where small groups of houses or isolated buildings were built in significant numbers between 3750 and 3600 bc. They have close parallels in northwest Wales but are not common in other parts of Britain (Whitehouse et al. Reference Whitehouse, Schulting and McClatchie2014; McClatchie, Barratt & Bogaard Reference McClatchie, Barratt and Bogaard2016). They are equally rare on the near-Continent, although domestic dwellings are often found in South Scandinavia. In most regions they were small rectilinear structures whose plans and dimensions were like one another. The main exceptions are large timber ‘halls’, most of which were built in Scotland, although they resemble buildings of similar date at Mairy in northeast France (Sheridan Reference Sheridan, Hofmann and Smyth2013; Bradley Reference Bradley2021: 109–17).

Other processes were shared between the island and its neighbours. At the beginning of this period, jadeitite axes from remote sources in the Alps were brought as far as Scotland. It seems likely that their production in such spectacular settings provided the inspiration for a similar development and quarries were established in Britain and Ulster (Pétrequin et al. Reference Pétrequin, Cassen and Errera2012). There is little evidence that insular products were taken across the Channel or the North Sea, but artefacts from these sources passed in both directions between England, Scotland, and Ireland. During the early fourth millennium bc there were flint mines close to the south coast; these were contemporary with similar complexes extending from Normandy to Sweden (Bostyn, Lech, Saville & Werra Reference Bostyn, Lech, Saville and Werra2023).

Monuments

In Britain few earthworks or megalithic structures date from this early phase. Although they developed in parallel with cereal farming, the scale of monuments was not necessarily related to the intensity of land use. With this qualification, the principal developments were the building of long barrows, chambered tombs, and earthwork enclosures. Their creation raises a new problem.

The simplest way of expressing this difficulty is to contrast the histories and distributions of these structures with the material culture found in them. Why did insular monuments have so much in common with those on the Continent when the associated artefacts differ from one region to another? For example, long barrows included comparable elements on both sides of the North Sea – elongated mounds, wooden facades, and mortuary structures made from split tree trunks (Rassmann Reference Rassmann, Furholt, Lüth and Müller2011) – yet each group was associated with a distinctive burial rite, and with material of kinds that conformed to local preferences.

Such patterning is not consistent with long-established approaches in which regional traditions are identified where distinctive styles of objects and monuments are found together over the same area. The method works well when it applies to ceramics and other artefacts, but in the early fourth millennium bc particular forms of stone or earthwork architecture transcended such local divisions. Special places – and the activities connected with them – made wider references.

This raises another issue. Enclosures, mounds, and chambered tombs existed long before the Neolithic settlement of the island and continued to develop in different ways afterwards. They originated at a specific juncture in the archaeology of the Continent. At one time the landscape had contained substantial dwellings and whole villages, but those elements had mostly disappeared when Britain was settled. They played little part in a more dispersed pattern of settlement, yet their original importance seems to have been recalled by public architecture.

The issues are familiar from the discussion of long barrows, whose shapes and sizes have often been compared with those of longhouses (Figure 4), but it is not certain whether the histories of these structures overlapped (Whittle Reference Whittle, Barclay, Field and Leary2020). The resemblance between them is undeniable, but the monuments were usually a subsequent development. Either their forms recalled those of dwellings which had been occupied in the past, or they exaggerated the characteristics of the smaller buildings that eventually took their place. Recent excavations have identified the remains of rectangular dwellings overlain by Neolithic mounds or cairns. These monuments recalled the positions, rather than the plans, of ordinary houses. Most are new discoveries, and it is possible that similar traces were missed during antiquarian projects (Bradley Reference Bradley2023a: 37–41). A similar approach could explain the relationship between roundhouses, circular cairns and passage graves along the Atlantic, although there is not enough information on the forms of domestic buildings (Laporte & Tinévez Reference Laporte and Tinévez2005).

Figure 4 The chambered tomb of Wayland’s Smithy, southern England.

These arguments focus on the histories of individual dwellings, but how was monumental architecture related to groups of dwellings? In this case, there are signs of a more complex sequence. The settlements of longhouses in northwest Europe were sometimes bounded by ditches. During later phases, the relationship between these elements changed. At first comparable enclosures were erected close to houses that remained in occupation, or on sites where such buildings had already gone out of use. Other examples surrounded entirely open spaces and contained few features apart from pits. Enclosure ditches were usually dug in segments separated by unexcavated causeways. The sites provided a focus for the kinds of activities that had once taken place in the settlements of more sedentary communities. They included feasting, craft production, and the commemoration of the dead. It was at this stage in the sequence that such monuments were constructed in Britain, where the first of them date from the thirty-seventh century bc (Whittle Reference Whittle, Lefranc, Croutsch and Demaire2023).

Why are these interpretations relevant to insular identities? They seem to emphasise the importance of the past. They assumed similar forms across large parts of northwest Europe. Perhaps people retained a notion of shared origins and identified themselves as part of a larger community. They drew on a notion of ancestry less precise than biological descent.

A Second Phase of Fragmentation (3600–3200 bc)

In fact such unity was more apparent than real because many of the new monuments conformed to regional groups within Britain. They may have expressed the same concerns as comparable structures on the Continent, but they also provide evidence of local alignments. For example, chambered cairns shared strong similarities between the west coast of Scotland and the north of Ireland. Long barrows, on the other hand, had comparable features to examples across the Channel and the North Sea.

Causewayed Enclosures and Cursuses

The distribution of causewayed enclosures is especially informative (Oswald, Dyer & Barber Reference Oswald, Dyer and Barber2001). Although there were a few examples in northern Britain, the majority were constructed in regions with the closest links to the Continent – southern and eastern England. In complete contrast, a new kind of monument originated in Scotland while those earthworks were still in use. Cursuses were long parallel-sided enclosures that resembled avenues or roads but were closed at both ends. The oldest were constructed of wood, but later examples were defined by ditches and banks (Brophy Reference Brophy2016). Eventually, their distribution extended into lowland areas where it complemented that of other monuments. In some regions, cursuses avoided the positions of causewayed enclosures. The contrast is particularly obvious since their plans were so different from one another. Most enclosures were approximately circular, but cursuses followed straight alignments (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Map illustrating the development of causewayed enclosures and timber cursuses

This development happened at a time when contacts with Continental Europe were diminishing. From this time cereal growing declined (Stevens & Fuller Reference Stevens and Fuller2012). The population may have been lower, and areas of farmland were becoming overgrown. Slight circular buildings could have replaced rectangular houses, although the evidence is limited. Flint mines and stone axe quarries gradually went out of use and there is less evidence for the long-distance movement of artefacts. Between 3700 and 3300 bc new styles of pottery developed in Britain. These vessels were made by contrasting methods between southeast and southwest England; Welsh ceramics were different again. On the other hand, production methods suggest new links between Scotland and Ireland (Pioffet Reference Pioffet2015). Lithic technology is less informative but suggests that contacts continued across the southern North Sea (Cleal Reference Cleal, Meirion-Jones, Pollard, Allen and Gardiner2012).

These changes emphasise developments along the south and east coasts of the island. One axis followed the Channel and is illustrated by the distribution of causewayed enclosures. The same applies to the main groups of flint mines which were within easy reach of the water. They were first used during the initial period of settlement but continued to function afterwards. A separate axis extended along the North Sea. In lowland England it was linked with causewayed enclosures, but further to the north it was more obviously associated with the development of cursuses. New work has identified cursus monuments in Ireland (O’Driscoll Reference O’Driscoll2024), some of which shared features with those in Wales. They might provide an indication of another, western axis.

Round Mounds, Single Graves

From about 3500 bc burial mounds in Britain assumed new forms. They were associated with a new mortuary rite which was practised for about five centuries (Gibson & Bayliss Reference Gibson and Bayliss2009). Long barrows had been associated with groups of bodies, and few were provided with grave goods. There was more variety. Circular mounds and cairns had been used before, but now they became increasingly important. All these structures were associated with single inhumations accompanied by special kinds of artefacts. This tradition was first recognised a century or more ago and thanks to development-led excavations it has now been identified across most parts of Britain; between 3600 and 3300 bc there was a similar development in Ireland (Brindley & Lanting Reference Brindley and Lanting1990). Single burials are best documented in the same areas as cursuses in England and Scotland and should date from the time when those earthworks remained in use. There is nothing to indicate links with mainland Europe.

Separation and Inclusion (3200–2500 bc)

Four developments set the course for the following centuries.

Cremation Cemeteries

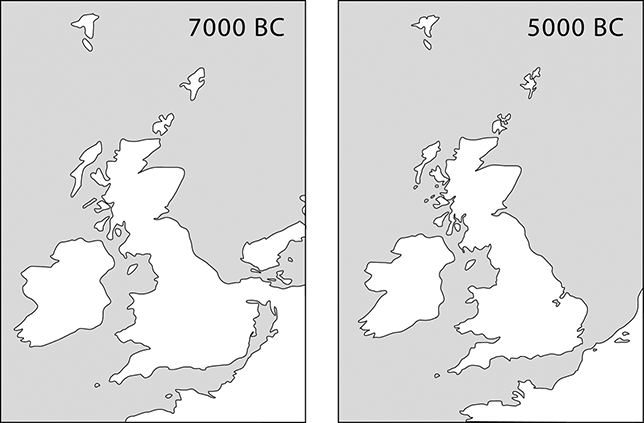

After an interval of uncertain duration, the richly furnished single graves at Duggleby Howe in northeast England were covered by a mound containing deposits of cremated bone (Gibson & Bayliss Reference Gibson and Bayliss2009). This was the clearest instance of a development which also featured in the earliest phase at Stonehenge. Research has identified other cremation cemeteries in Britain (Willis Reference Willis2021). While there is considerable variation, most of them date between 3100 and 2700 bc. They were associated with small circular monuments: low mounds, earthwork enclosures of various kinds, stone settings, and rings of wooden uprights. Again, many examples were near to older cursuses.

Their establishment represents a new departure in Britain, but more radical developments were happening further to the west. Relationships with Ireland became increasingly important, and so did links between Wales, northern Scotland, and lowland England. Their chronologies are not entirely clear, and each of these connections must be treated separately.

Passage Graves and Associated Monuments

Chambered Tombs

Connections with Ireland were restored after a period of isolation during the late Mesolithic period. After farming had been introduced to Britain and Ireland, the inhabitants of both islands used the same kinds of artefacts and domestic buildings. Chambered tombs played an especially important role. The evidence is strongest in the case of passage graves, which had a wide distribution among early farmers in Western Europe (Schulz Paulsson Reference Schulz Paulsson2017). Irish examples echoed their characteristic forms but had a longer currency than their counterparts in the nearest regions of the Continent – the north and west of France. Many monuments were in cemeteries, the most elaborate of which were in the Boyne Valley not far from the Irish Sea. Here the most elaborate structures were erected between about 3200 and 2900 bc (Eogan & Cleary Reference Eogan and Cleary2017). It seems possible that the fame of the greatest monuments – Newgrange, Knowth, and Dowth – extended beyond Ireland altogether as their architecture and a few associated objects have parallels in the Iberian Peninsula. On a smaller scale the increasing importance of cremation was shared between Britain and Ireland.

Passage graves were elaborate constructions. Bones were housed inside stone chambers concealed beneath substantial mounds or cairns but accessible from the outside world. Almost twenty per cent of the Irish examples were aligned on the midwinter or midsummer solstices. Certain sites were decorated with abstract motifs interpreted as evidence of a shared cosmology (Robin Reference Robin2009). The tombs include the remains of a small number of individuals. A few of their bones had not been burnt and could be analysed for ancient DNA. A new study shows that some of the people whose remains were deposited in separate cemeteries in Ireland were distantly related to one another (Cassidy et al. Reference Cassidy, Ó Maldúin and Kador2020).

Irish tombs remained in use in the early third millennium bc and by this stage, they were addressed to larger audiences. There was a new emphasis on the spaces outside them where there were deposits of quartz, stone-lined hearths, and platforms associated with evidence of feasts (O’Kelly, Cleary & Lehane Reference 79O’Kelly, Cleary and Lehane1983). Beyond the tombs were palisaded enclosures, timber circles, and the conspicuous earthworks described as henges (Davis & Rassmann Reference Davis and Rassmann2021).

Few of those elements were shared with Continental Europe, but there were obvious links with northern and western Britain. The closest relationships were between the builders of passage graves in the Boyne Valley and the inhabitants of Orkney (Figure 6). There is no reason to suppose that new practices and beliefs were transmitted in a single direction, and it seems likely that two largely independent sequences converged during the late fourth millennium bc. Just as monument building in the Boyne Valley drew on earlier developments in Ireland, the major structures in Orkney had local antecedents.

Figure 6 The passage grave of Maeshowe, Orkney.

The greatest passage tombs in Orkney, like Maeshowe and Quanterness, are compared with those in the Boyne Valley (Edmonds Reference Edmonds2021). They were contemporary with one another, and their forms were similar. Some of them were decorated with incised motifs like those inside the large monument at Knowth. Most of the structures were associated with circular mounds. Both groups incorporated solsticial alignments, but there were differences between these buildings. The layout of the chambers resembled local house plans and contrasted with the organisation of space inside Irish tombs (Richards & Jones Reference Richards and Jones2016). Orcadian monuments did not form parts of larger cemeteries. The associated burials contrasted, too. The cremation rite predominated in Ireland, but in Orkney bodies remained intact, although disarticulated bones might be rearranged: a practice that began at older long cairns.

If Irish passage graves were often grouped together, their equivalents in Orkney were separate, and some were close to settlements. Portable artefacts carried the same designs as tombs and houses. At the end of the fourth millennium bc new structures were built around large Irish monuments, although the mounds and cairns retained their importance for a long time afterwards. There was a similar development at Orcadian passage graves, which could be supplemented by an external platform or a ditch. Like Newgrange, Maeshowe might have been enclosed by a setting of monoliths (Richards Reference Richards2013: 229–59). A massive walled enclosure was established nearby on the Ness of Brodgar (Card, Edmonds & Mitchell Reference Card, Edmonds and Mitchell2020). It was probably a ceremonial centre and contained a series of specialised buildings which have been compared with those identified by aerial photography close to Newgrange (Davis & Rassmann Reference Davis and Rassmann2021).

This is not the only evidence of connections across the sea. A local style of decorated pottery – Grooved Ware – was eventually introduced to Ireland together with decorated stone artefacts (Copper, Whittle & Sheridan Reference Copper, Whittle and Sheridan2024.). Other regions played an important part. Rock art with designs related to megalithic art is represented by the west and east coasts of Britain and along the land routes leading between them (Bradley Reference Bradley2023b). Further links are suggested by structures around the Scottish and Irish coasts, most of which could be accessed by boat.

Henges

Earthwork enclosures indicate other connections. Although embanked ‘henge monuments’ have been identified close to passage graves in Ireland, most have still to be investigated and only one unusual example has any dating evidence. It was built between 2950 and 2850 bc (Cleary Reference Cleary2015). Such structures have been identified in the Boyne Valley and can be compared with a small number of earthworks in northern England and southwest Wales (O’Sullivan, Davis & Stout Reference O’Sullivan, Davis, Stout and Gibson2012).

A second group of circular earthworks suggests another axis. They have been called ‘formative’ henges because they predate better-known examples in Britain; their other feature is that they have internal banks and external ditches. Their distribution extends from northwest Wales to Wessex (Burrow Reference Burrow, Leary, Darvill and Field2010a). Little is known about them, but those with radiocarbon dates were first built by 3000 bc. They include two excavated monuments. At Bryn Celli Ddu on the island of Anglesey one of these enclosures contained a small passage grave and a stone circle associated with cremation burials (Burrow Reference Burrow2010b). The tomb was enlarged around 3000–2900 bc and resembles structures of the same age in Ireland (Figure 7). A second example was Stonehenge where a circular enclosure with a segmented ditch was built at about the same time. It seems to have contained another ring of standing stones which were introduced from southwest Wales. The new structure was associated with cremation burials like those at Bryn Celli Ddu – links between western Britain and other regions were not confined to the Irish Sea. In this case, they were emphasised by the transport of building material (or a dismantled monument) over 200 km (Parker Pearson et al. Reference Parker Pearson, Pollard and Richards2020).

Figure 7 The sequence at Bryn Celli Ddu, Anglesey, showing the positions of the cremation burials.

Later Connections

After an initial phase, elements that had originated in Orkney were adopted in other parts of Britain. They were associated with the same ceramic tradition – Grooved Ware – but assumed different forms. Towards the east coast there is less evidence of monumental architecture (apart from a group of henges with two concentric earthworks which have not been dated). There were mines and other sources of high-quality flint close to the water and artefacts made there were distributed along the North Sea from southeast England to northeast Scotland (Gardiner Reference Gardiner2008).

The most conspicuous monuments were henges with one internal ditch and an external bank (Figure 8). There were also large palisaded enclosures, some of which were erected in the same places. For the most part they were established in regions with cremation cemeteries and major cursuses. There were important contacts along both the Atlantic and the North Sea. Connections with northern Scotland are illustrated by rock art which included unusual motifs associated with Orkney chambered tombs. Some of the decorated outcrops were by sheltered inlets while others followed land routes leading through the high ground (Bradley Reference Bradley2023b).

Figure 8 Henge monument enclosing a stone circle at Arbor Low, northern England.

The largest monuments could have been visited from distant regions, and the structures found inside them – especially the stone or timber circles – had similar plans across Britain and Ireland. A few resembled one another so closely that they might have been intended as copies; the distances between such pairs were between 250 and 400 km (Bradley Reference Bradley2024). Certain henges provide evidence of feasts. Isotopic analysis shows that animals were brought over considerable distances (Madgwick et al. Reference Madgwick, Lamb and Sloane2019). Large work forces were needed to build these structures, and numerous people must have taken part in ceremonies. Most of the biggest henges and palisaded enclosures were in the west and south of Britain, but timber circles are also found towards the east. Fewer of them were enclosed and they might have had different histories from the others.

The erection of important monuments made great demands, and it is not always clear where suitable material was found. The transport of monoliths to Stonehenge was not a unique instance. Other settings combined rock from several sources, and examples from Orkney to southwest England suggest that individual monuments combined the efforts of several communities and might have been designed as microcosms of a wider landscape. At times these connections are especially revealing. Stonehenge itself employed building material obtained close to a great monument of the same date at Avebury (Nash et al. Reference Nash, Oborowski and Ullyott2020).

Avebury was within sight of the greatest artificial mound in prehistoric Europe. It introduces yet another issue. Silbury Hill was one of a small group of earthworks in central southern England, although there are possible parallels in north Wales and southwest Scotland (Leary, Field & Campbell Reference Leary, Field and Campbell2013). It was constructed between 2500 and 2400 bc, at a time when Newgrange remained significant (Carlin Reference Carlin2017), but unlike that famous monument Silbury was not associated with any burials.

The Implications of Stonehenge

The principal monument at Stonehenge is dated between 2580 and 2475 bc (Figure 9). How is it relevant to identities in prehistoric Britain? Following a prescient suggestion of Childe, Parker Pearson argues that at different times it celebrated the unification of regional traditions within Britain (Parker Pearson Reference Parker Pearson2023: 158–60; Parker Pearson et al. Reference Parker Pearson, Bevins and Bradley2024). The process started with the introduction of bluestones from Wales, and in a later phase it brought together building materials from other sources. It combined structural elements that had developed in timber buildings throughout Britain and Ireland and made unique demands on human labour, organisation, and skills (Gibson Reference Gibson2005). It united disparate elements in one unprecedented project. It seems possible that other monuments played comparable roles but on more local scales, and it is no accident that most of them were located in between two separate networks. One followed the North Sea, and the other connected Wales and western Scotland to Ireland. Although there were close links across the Irish Sea, Britain was isolated from the Continent.

Figure 9 Stonehenge:

Discussion

The opening section of this Element asked how the archaeology of prehistoric Britain was related to that of other parts of Europe. The Mesolithic and Neolithic periods show how difficult it is to provide any simple answers. There were significant changes in the shape of the land and the contacts between people who occupied different regions. There were connections that the inhabitants chose to foster and those they decided to neglect. Few of the new alignments correspond to national boundaries today and in a period when travel by sea was important the distinction between islands and the mainland was not necessarily significant. During the Neolithic period the inhabitants were free to ally themselves with other communities or to keep their distance. Thus, Britain had few contacts with Ireland between 6000 and 3800 bc, and then the two islands had close links until the late fourth millennium. At that stage, they became caught up in a series of dramatic developments that had nothing in common with events in mainland Europe.

If people could decide between promoting or rejecting long-distance contacts, their decisions were influenced by several factors. One was the ease or difficulty of travelling between Britain, Ireland and the Continent. At an early stage there was an obvious emphasis on the securest routes. By the Late Neolithic, however, more arduous journeys were undertaken, especially those around the north of Scotland where a series of monument complexes developed in remote locations. Going there involved a challenging passage by sea. This must have been one of the reasons why these places became so important. It is vital to recognise the entire range of possibilities. People and their livestock crossed the water where it was safest to do so, but visitors to special locations – quite possibly pilgrims – might have invited difficulties as a way of asserting their beliefs (Bradley & Watson Reference Bradley and Watson2024).

Other connections involved the forms of monuments rather than the locations in which they were built. The appearance of long mounds and causewayed enclosures evoked structures occupied long before farmers settled in Britain. In the same way, passage graves were still erected in the north and west of the island after they had gone out of use in the nearest parts of the Continent – they may have had a similar significance. Other kinds of connections formed during the late fourth and early third millennia bc when the layout of impressive monuments acknowledged the positions of the sun at the turning points of the year. Ideas about the working of the cosmos united the occupants of different regions, even if they rarely met.

Which networks were most important, and did they extend beyond this offshore island? Do they lend any support to the idea of British self-sufficiency? In fact, there were several changes of alignment during the Neolithic period. After the social and physical disruption caused by sea level rise there were remarkably close links between the island, its neighbour to the west, and the European mainland. That is generally accepted, but it is harder to explain why they weakened over time. Nor is it clear why more local networks developed. One was associated with the invention of a specifically insular kind of monument. Cursuses were most clearly evidenced along the North Sea coast from Scotland to Wessex. Their adoption in southern England seems to have disrupted the connections with the Continent epitomised by causewayed enclosures. Another axis was developing in the west. It is most clearly evidenced by megalithic tombs. Its origins lay in links with Atlantic Europe and more immediately with Ireland. In Britain, there was a noticeable contrast between these zones.

That was especially true in the north where communications between the east and west coasts were difficult because of the high ground in between them. But other alignments are equally revealing. There were fewer regional distinctions within lowland England where it was comparatively easy to travel along the river system. In the far north the sea played a greater role, and in the centuries around 3000 bc Orkney had closer links with Ireland than with parts of mainland Scotland. At a time when relations with the Continent had lost their attraction, there was more interchange across the Irish Sea. During the Neolithic sequence British communities seem to have switched their attention from one neighbour to another. Instead of initial connections with France, Belgium, and the Low Countries there was a stronger relationship with Ireland.

In the end events took an unexpected turn. In many parts of Britain enormous monuments were erected during the mid third millennium bc. They conformed to local types but seem to have been the outcome of the same stimulus. Their construction might have promoted a new unity, but this development was provoked by developments outside the island altogether. The settlement of new people from the Continent changed the nature of insular prehistory.

3 Far and Near (2500–1200 bc)

2500–2200 bc

Bell Beakers

Discussions of long-distance contacts are complicated by questions of terminology. During the third millennium bc similar styles of pottery were important in two parts of the Continent. In Northern Europe there was Corded Ware and further to the west there were Bell Beakers (Vander Linden Reference Vander Linden2024). The relationship between them is not clearly understood. Where did they originate? Were they employed in sequence, or were they used at the same times but in different regions?

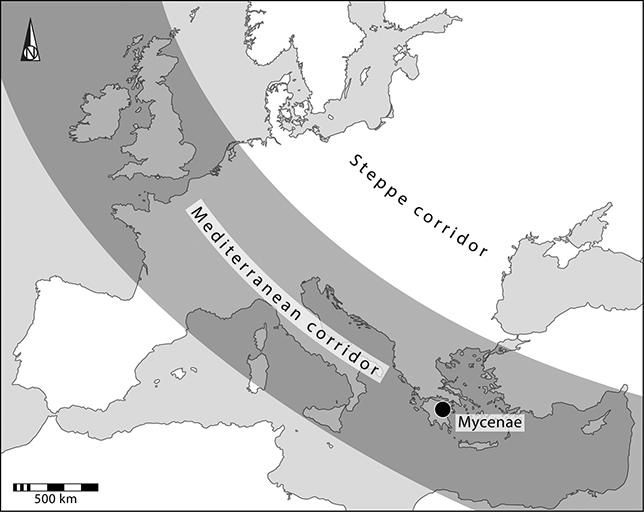

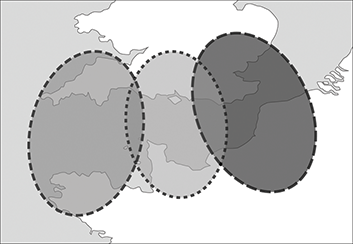

In Britain these questions are seldom asked because Corded Ware is absent, and the Bell Beaker tradition was introduced from the mainland. But these pots and their associations raise a special problem. How were they related to Continental styles and what light does their adoption shed on relations between this island and other parts of Europe (Figure 10)? The difficulties are illustrated by a scheme devised by Clarke (Reference Clarke1970).

Figure 10 The distribution of Bell Beaker pottery.

His classification of these vessels mixed three different elements. First, he described their decoration. There were All-over Corded Beakers and Barbed Wire Beakers. A second group comprised styles shared between different parts of Britain and regions of the Continent: as well as European Bell Beakers, there were Wessex / Middle Rhine Beakers, Northern / Middle Rhine Beakers, and Northern / Northern Rhine Beakers. He defined another tradition which he termed Primary Northern British / Dutch. He argued that all these styles were associated with groups of immigrants who introduced new burial rites and the earliest metalwork. He also identified local sequences in Southern and Northern Britain, respectively. Another regional type was the East Anglian Beaker.

His classification was too complex, and from the outset some of its elements were questioned by Continental scholars. As a result, simpler chronologies were proposed, first by Case (Reference Case1993) and then by Needham (Reference Needham2005). Their interpretations are supported by radiocarbon dating. Needham followed previous writers in accepting an initial phase of settlement from the mainland. Like Case, he recognised the importance of contacts across the Channel and the southern North Sea, as well as other links extending along the Atlantic. He identified three successive developments in Britain. Between 2500 and about 2300 bc Bell Beakers and their associations were like those in mainland Europe. They indicated a period of migration and hardly overlapped with the material culture of the indigenous inhabitants. This distinction broke down between 2300 and 1950 bc, when there were signs of greater diversity. Lastly, between 1950 and 1700 bc, Beaker traditions were absorbed into insular culture.

Needham’s scheme met with general acceptance and is supported by new studies of ancient DNA. This research extends to most regions of the Continent and provides compelling evidence of settlers whose genetic inheritance can be traced to southeast Europe (Olalde et al. Reference Olalde, Brace and Allentoft2018). Despite important differences between their mortuary rites, the people buried with Bell Beakers and Corded Ware shared ancestors in the steppes. The British results were distinct from those obtained for local burials of Early and Middle Neolithic dates (almost all Late Neolithic burials were cremations). Still more striking, the genetic evidence did not document a significant contribution from the native inhabitants for about 500 years. Of course, this method could not study cremated bone and the inhumations associated with Beaker pottery included relatives who had been buried together in the same cemeteries (Booth, Brück, Brace & Barnes Reference Booth, Brϋck, Brace and Barnes2021). But the new scheme agrees with Needham’s interpretation of the artefacts in graves. It is also consistent with isotopic evidence of first-generation immigrants associated with Beaker vessels.

This evidence is particularly striking because communities in Britain had few outside contacts during the Late Neolithic period when their wider connections were apparently restricted to Ireland. There are no indications of any links with mainland Europe. At the same time the forms of the main insular monuments – from cursuses to henges and from palisaded enclosures to stone circles – lacked close counterparts on the European mainland. A possible exception is a great timber circle at Pömmelte in central Germany (Spazier & Bertemes Reference Spazier and Bertemes2018), but even its form may have been inspired by the remains of the Continental earthworks known as roundels which had been used at an earlier date (Schier Reference Schier2023). The insular henges and stone circles had originated by 3000 bc, but the first examples were mainly in northern and western Britain. Later monuments show a remarkable contrast. They were more elaborate and building them required bigger labour forces. The same elements were shared across larger areas. Radiocarbon dating suggests that they were erected over a short period during the mid to late third millennium bc. They were associated with a local ceramic style, Grooved Ware.

There was a dramatic escalation in the scale of special buildings. Their dates suggest that they were constructed at a time when people were becoming aware of new practices on the Continent. They would also have encountered groups of immigrants within Britain itself. Certain monuments were unusually short-lived. Others were erected after the first settlers had arrived. The simplest interpretation is that this emphasis on new projects was a reaction to the influence of unfamiliar people and strange beliefs – it reasserted insular traditions on an unprecedented scale (Greaney et al. Reference Greaney, Hazell and Barclay2020). Although there are few indications of violent conflicts, local identities were threatened, and British separateness was gradually undermined.

New Networks

This was the second major phase of immigration from the Continent, but it followed a different course from the settlement of the first farmers a millennium and a half before. The Bell Beaker occupation of Britain appears to have been more rapid and covered a greater area. A new study shows that the burials of the first immigrants were widely distributed (Parker Pearson et al. Reference Parker Pearson, Sheridan and Jay2019). If the best-known example is the Amesbury Archer whose grave was in Wessex (Fitzpatrick Reference Fitzpatrick2011), another was on a Hebridean island. A striking number of Beaker sites were by the sea. Some of those locations had been utilised as landing places and harbours during earlier periods, but the use of others was new (Bradley, Rogers, Sturt & Watson Reference Bradley, Rogers, Sturt and Watson2016).

The sources of these settlers were as diverse as those of the Early Neolithic phase. The separate styles defined by Clarke placed an emphasis on the Netherlands and the Rhineland. He also distinguished between artefact assemblages in northern Britain and those found further to the south: a contrast echoed in Needham’s subsequent analysis. Case stressed the importance of a second network extending up the west coast of Europe from Iberia. This network impinged on southern England. In the Late Neolithic phase there is evidence of travel around the British and Irish coasts, but the new connections were not the same. Contacts along the North Sea and the Channel increased in importance, and the close links between Orkney and the Boyne Valley lapsed. Of greater significance were those between Britain and the Continent. They allied the offshore island with areas as far from one another as the Netherlands and Brittany. Although relations with Ireland had been important, there could not be a greater contrast with the insularity of Britain during the previous phase.

Houses and Burials

At the same time, there were regional contrasts during the Beaker period. The distributions of portable artefacts have played a prominent part in the discussion, but other features are more revealing. The main sources of information are the forms of settlements and houses, and the treatment of the dead.

A recent publication discussed Bell Beaker houses in different parts of Europe (Gibson Reference Gibson2019). One feature shared between Britain, Ireland and the near-Continent is the rarity of recognisable dwellings. Most occupation sites are marked by scatters of artefacts, and features such as post holes, hearths, and pits are comparatively uncommon. Domestic buildings have been identified in Denmark and Brittany but are unusual in other places; they are equally infrequent in Ireland. For the most part their forms were like those of older structures in the same regions, and this applied to the few circular or oval examples in Britain. In western Scotland, however, a new type has been recognised. It was approximately boat-shaped. Few have been excavated, but they compare with houses of the same kind in Brittany and Normandy. The evidence from other parts of the Continent shows a fundamental contrast. Although domestic buildings are uncommon in the Netherlands – one of the regions with the strongest connections to Britain – the excavated structures were really longhouses. They are so rare that they may have played an exceptional role. Although the evidence for domestic buildings is limited, there was no single type of Beaker house in Europe.

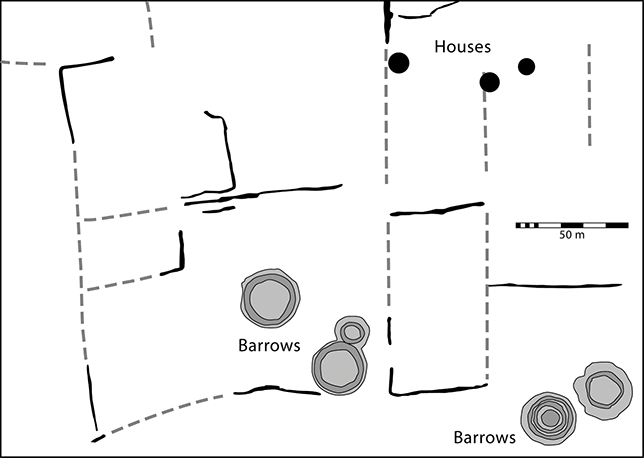

Burial rites did not conform to the same regional distinctions. Individual inhumations, associated with pottery, ornaments, and metalwork were widely distributed. They took similar forms throughout Britain and the nearest parts of the Continent but were unusual in Ireland. The most complex burials were placed inside wooden chambers or coffins and some of them were associated with circular mounds or enclosures; others were in flat graves which could form parts of larger cemeteries (Figure 11; Vander Linden Reference Vander Linden2024). Single burials were a new development in Britain where their only equivalents had gone out of use 500 years before (Brück Reference Brück2019: 16–50). On the other hand, groups of round mounds in the Netherlands were already associated with Corded Ware. Some of these earthworks were reused during the Bell Beaker period, and more were constructed at that time (Bourgeois Reference Bourgeois2013).

Figure 11 Early Bronze Age barrows on the Wessex chalk.

A different tradition is recorded along the Atlantic coast. In western France, there were collective burials as well as the single graves that characterised other regions. Many of these deposits were associated with the remains of older monuments. Chambered tombs saw a second period of use. Their chronology is revealing since there seems to have been a preference for older monuments rather than those erected during the recent past (Gibson Reference Gibson, Koch and Cunliffe2016). The evidence reinforces the distinction between one network based on the Channel and the southern North Sea, and another along the Atlantic. There was little overlap between the axes indicated by graves, and those defined by domestic dwellings.

Copper

It is often supposed that the settlement of people from the Continent is explained by the search for metals, but the earliest evidence for the extraction of copper comes from southwest Ireland around 2400 bc and predates the establishment of similar mines in Britain by 300 or 400 years. The Irish site was at Ross Island where the mines were associated with a work camp in which the ore was processed (O’Brien 2004). It was associated with Beaker pottery and with a distinctive technology practiced in parts of Atlantic Europe.

The adoption of metalwork provides further evidence of connections between Britain and its neighbours. Copper was taken across the Irish Sea, but certain artefacts shared a distinctive composition defined as ‘Bell Beaker metalwork’ (Needham Reference Needham, Allen, Gardiner and Sheridan2012). It could have combined material from several sources. That raises a problem, but its distribution suggests links between Britain, Holland, and Normandy. It provides a further indication of the affinities between insular communities and those in accessible regions of the Continent.

2200–1600 bc

Metals remained important during this phase. At one time the distribution of the earliest goldwork suggested a source in Ireland, but newer research favours an origin in southwest England (Standish, Dhuime, Hawkesworth & Pike Reference Standish, Dhuime, Hawkesworth and Pike2015). That connection is revealing as the same area became a major source of tin from 2200 bc. It was alloyed with copper and widely distributed in Western Europe. This marks the beginning of the insular ‘Bronze Age’. Far from emphasising British isolation, it was a precocious development and anticipated technological changes in neighbouring regions by 200–300 years (Pare Reference Pare and Pare2000). About 1900 bc the copper mines at Ross Island had been replaced by the first examples in Wales and northern England; others were established in Ireland from 1800 bc (Timberlake Reference Timberlake2016). They operated on a smaller scale and insular communities became increasingly dependent on supplies from the Continent.

The same kinds of artefacts were associated with harbours and landing places on the coast. Most of these sites had been used before (Bradley, Rogers, Sturt & Watson Reference Bradley, Rogers, Sturt and Watson2016). Such locations were set apart from settlements and monuments of the same date and could have been where strangers met to exchange artefacts. The distribution of these places is limited to areas in which the ancient shoreline survives but ‘maritime havens’ of this kind are recorded along the North Sea and both shores of the Irish Sea.

The Power of the Past

One reason why scholars had been reluctant to countenance episodes of migration from the Continent was the frequency with which Beaker and Early Bronze Age artefacts were discovered at Neolithic sites. The greatest concentrations of burials focused on stone or earthwork structures surviving from the past. The area around Stonehenge provides the obvious example of this relationship (Booth, Brück, Brace & Barnes Reference Booth, Brϋck, Brace and Barnes2021). The contents of local graves have been studied for ancient DNA. Laboratory analysis showed that the people buried there were not related to the original builders of the monument. They might have owed their authority to an invented past. Radiocarbon dating of individual grave goods together with human and animal bones reinforces this impression, for it shows that some of the deposits contained heirlooms or relics which had been taken from other contexts. The artefacts could be worn or broken and some of the necklaces accompanying the deceased combined beads from different sources (Woodward & Hunter Reference Woodward and Hunter2015). This concern with a remote past was not confined to Britain, and the same model explains why Breton megalithic tombs were reused during the Beaker period (Gibson Reference Gibson, Koch and Cunliffe2016).

At the same time, those developments focused on certain regions of Britain at the expense of others. It is often supposed that older styles of monuments lapsed by the Early Bronze Age and that new ones were no longer built. That was largely true in lowland England, but henges and stone circles were still constructed in other areas. They resembled their predecessors but were conceived on a smaller scale. It seems as if established practices and beliefs retained their power in the north and west after their abandonment in the south (Bradley & Nimura Reference Bradley and Nimura2016).

Settlements, Houses, and Landscapes

The archaeology of this period in Britain is dominated by burial mounds, and it has been surprisingly difficult to investigate the settlement pattern (Brück Reference Brück2019; Johnston Reference Johnston2021). The same problem affects research in other parts of Europe, especially Ireland, France, and the Low Countries. There is no shortage of living sites, but in most cases all that survive are collections of artefacts. A common response has been to infer a mobile pattern of settlement in which the raising of domesticated animals was more important than cultivation. Finds of cereals are uncommon although they do occur, but the argument is largely circumstantial. Stable isotopes provide a more reliable source of information. On the Continent this kind of study has been undertaken for two main reasons – to investigate prehistoric migrations and the exchange of individuals between communities (Stockhammer & Massy Reference Stockhammer, Massy, Fernández-Götz, Nimura, Stockhammer and Cartwright2022). In Britain it sheds more light on mobile land use. A new analysis of burials dating from the late third and early second millennia bc showed that people could have lived in several regions over the course of their lives (Parker Pearson et al. Reference Parker Pearson, Sheridan and Jay2019). At the same time, they might be buried outside those areas. What led to that decision? Perhaps it was determined by the continuing influence of the past, as some of the most elaborately furnished graves were associated with monuments built during the Neolithic period.