1 Introduction: Early English Periodicals and Early Modern Social Media Forms

Social authors take advantage of the interactive elements afforded by Web 2.0 infrastructures to form an online community. … These authors’ online connection to their audience is not driven by their royalty publisher, but by their own choice to expand the author – reader dynamic.

What can one learn from [this] early culture of authorship that is relevant to our current situation? Are we returning to the early modern model of manuscript text and social authorship?

In 1999, I concluded my study of a feature of late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century literary culture, social authorship, by wondering what, if any, application that model might have for the emerging digital publication media at the turn of the twentieth century. I argued then that English literary culture in the early modern period was marked by a vibrant literary culture based on the circulation of handwritten, manuscript copies, which complemented and competed with a burgeoning print market for the attention of writers and readers. In this model of coterie or social authorship, readers were also writers, editors, and curators of their own and their coterie’s literary productions, not merely passive, paying consumers of it. This is not the same as “scribal publication,” where professional scribes reproduced handwritten manuscript texts that were commissioned or purchased by readers, often clandestinely; instead, social authorship, as its name implies, values interactive, reciprocal forms of literary exchange with no financial aim, a form of literary culture that we now know continued well into the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.Footnote 2

In this brief study, I would like to apply this concept of social authorship to explore, paradoxically, a highly commercial form of print media which became popular in England at the end of the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, the periodical. In particular, I will look at how in its early stages, periodicals made use of the practices found in the older social manuscript literary cultures to attract and sustain a paying readership. Questions quickly suggest themselves when we observe how this genre changed over time: How did an originally cheap form of printed ephemera become a collectible literary commodity, with some of its authors such as Joseph Addison, Richard Steele, and Samuel Johnson, joining the ranks of canonical English writers? What were the expectations of the original periodical readers of the genre as compared to today’s academic ones? Why do many of the strategies and tactics employed by early periodical writers and publishers to create and sustain an audience seem so familiar to us now, during a transition period from commercial print to digital media?

Those familiar with early modern authorship practices in general, including social authorship and scribal publication, find themselves surprised by the enthusiasm which the commentators on digital media have typically declared that the shift from paper to screen, from print to digital, is a “revolutionary” phenomenon, creating a new forms of literacy, journalism, and of course, literary culture – as the nerdy genius Egon in the film Ghostbusters announced in 1984, “print is dead,” and it is commonplace to assert that “no one” now reads except on a screen.Footnote 3 While indeed the digital media ecology is transforming the traditional print one as found in the twentieth century, is it as original and unprecedented in its practices, as is often declared?

This is not intended as an in-depth scholarly comparison between early eighteenth-century print and twenty, twenty-first digital media, but instead an experiment to see what emerges when one thinks about the practices and issues for writers and readers of each, what might a juxtaposition of observations about the ecology or behavior of each might cause us to see occurring in the other. Rather than only looking for transhistorical parallels, by using the lens of digital authorship practices in the age of contemporary social media, we may also disrupt in a positive way traditional formulations of eighteenth-century periodical writing, which would then permit us to see aspects of past practices usually overlooked. Referencing features of participatory culture in the digital age, I hope, highlights those within late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century literary ecologies which permitted and propelled the popularity of those periodicals while shaping their contents. Observing the nature of the dynamics of earlier periods’ literary ecologies may well also serve as a gentle corrective to the often-ahistorical understanding of our own literary ecology that is manifest in discussions of digital authorship practices. Finally, we see in the changes between practices found in the early periodicals such the Gentleman’s Journal and those in the Rambler a different type of relationship between readers and authors, which, while gesturing at the expected formal elements established in the earlier periodicals, rejected the dynamics of participatory literary culture for creating content.

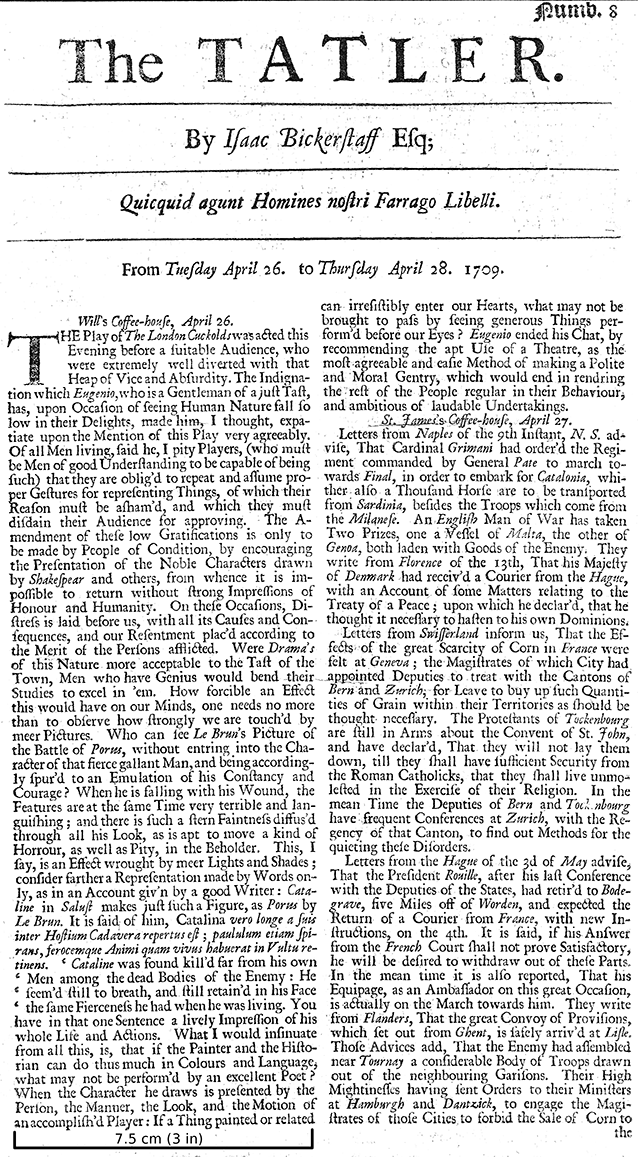

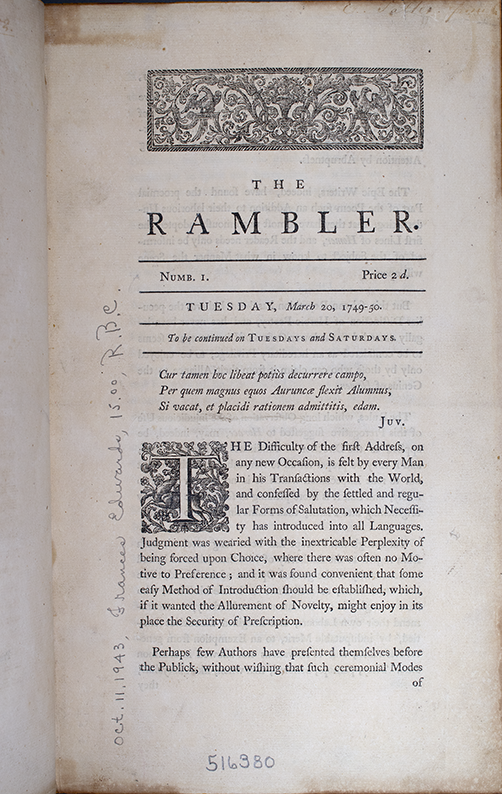

Most twentieth- and twenty-first-century readers who are familiar with the early periodicals I will explore know them through the classroom and know only a tiny fraction of the writers who were engaged in creating them. One thing that clearly emerges is that in our modern teaching anthologies and in most critical discussions of the origins of periodicals, the entries under the names Addison and Steele consist only of a portion of the original contents of the Spectator or Tatler. Typically, only the essay in each issue is offered to modern readers, with no mention of the other contents that characterized the periodical form, the flower cut off, as it were, from a complex literary ecosystem. Modern readers are presented with short pithy essays conveniently packaged as examples of timeless, enduring English “literature” that serve as exemplary English prose models: in fact, in their complete and complex original publication format, the Tattler and the Spectator were ephemeral publications that were competing for readership in an aggressively expanding “new” media market. Likewise, grouping Samuel Johnson with Addison and Steele as the masters of the periodical essay based on the essays’ contents and narrative voices obscures not only what these authors shared as writers for periodical publications, but also the ways in which Johnson chose to deliberately reject many of the conventions that his predecessors had used so successfully, signaling a significant change in the nature of the periodical genre in the process.

1.1 General Characteristics of Early English Periodicals

British Newspapers and Periodicals 1641–1700: Short Title Catalogue (1987) broadly defines periodicals from this period as being “numbered and/ or dated issues of proposed or actual sequences of pamphlets or sheets, bearing uniform titles and formats.”Footnote 4 It has been estimated that approximately “one-quarter of the publications in Britain between 1641 and 1700 were issues of serials (or ‘periodicals’ in British usage),” offering multiple formats for readers to choose from: “over 700 such titles were published, including newsbooks, newspapers, literary and leisure miscellanies, trade bulletins and official journals.”Footnote 5 Although as we shall see, subsequent commentators have assigned this new genre significant cultural weight, it was originally an ephemeral product. It is important to realize that the term “periodical,” according to the Oxford English Dictionary, did not come into widespread usage until the latter part of the eighteenth century to signify “a magazine or journal issued at regular or stated intervals (usually weekly, monthly, or quarterly).” Seventeenth- and eighteenth-century readers and writers, however, generally referred to them simply as “papers.”

As the editors of a recent collection of essays on women’s periodicals in the eighteenth century have noted, “periodical” “is a deeply difficult term to define in the eighteenth-century context: It can reasonably be argued to encompass everything from the news-sheet, to the advice column, to the essay periodical, or the magazine or even pseudo-periodicals.”Footnote 6 They characterize periodicals in the long eighteenth century as being comprised of “hundreds of titles, many short-lived and hard to trace; others stunningly voluminous and hard to summarize.” They urge that rather than attempt to divide these ephemeral publications into discreet subgenres, such as newspapers versus literary periodicals versus magazines, the periodical should be understood in an eighteenth-century context: that “periodical culture” was composed of “diverse but contiguous” forms. I would suggest that this is not unlike our evolving digital media culture, as My Space competed with Facebook, and YouTube spawned TikTok.

That said, some general characteristics can be cautiously suggested when one is speaking of the type of early eighteenth-century periodical publications, which have been enshrined within traditional literary histories and classroom anthologies. These periodicals typically appeared weekly, if not more often – the Tatler, for example, was published three days a week and the Spectator initially appeared daily – and they appeared on specific days announced in the publication. They were typically printed either with two columns, front and back, on a single folio half sheet, as were the Athenian Mercury and the Spectator, or as a small quarto pamphlet, such as Daniel Defoe used for the Review. They were relatively inexpensive publications: It is estimated that the Spectator cost two pence each issue, but it is also the case that many people enjoyed reading them for free, courtesy of their favorite coffee house which often offered a wide array of ephemeral printed materials for the entertainment of their customers. They were not intended to be primarily a private reading experience but, as Abigail Williams has suggested about eighteenth-century reading practices in general, a shared one, whether reading aloud in the family or listening to others in public spaces.Footnote 7

1.2 English Periodicals in Literary History

The names “Addison and Steele,” like Shakespeare’s contemporaries Beaumont and Fletcher, are inevitably coupled in literary histories. Together, these two friends and collaborators, Joseph Addison and Richard Steele, and the essays they published in the periodicals the Tatler and the Spector helped create later generations’ perceptions of both the early eighteenth-century culture in which they lived, and the genre in which the wrote, the periodical essay. In essays of around 2,500 words, they presented their views on contemporary topics ranging from the silliness of Italian opera and contemporary women’s hair styles to the poetics of Milton’s Paradise Lost and the importance of commerce and the merchant class in England.

The eighteenth-century periodical essay has long been considered by literary critics to be a new English literary genre that, like the novel, arose out of rapidly changing social structures in the early eighteenth century. Its contents have been typically described as providing a particularly good window into the manners and tastes of its original readers. In addition, canonical authors have been seen as helping to shape those tastes, acting as powerful social influencers, Terry Eagleton, echoing a nineteenth-century biographer’s observation that Addison was the “chief architect of Public Opinion in the eighteenth century,” endorses the essential point that the Spectator determined the topics and attitudes of “this ceaseless circulation of polite discourse among rational subjects … the cementing of a new power bloc at the level of the sign.”Footnote 8

In terms of genre, the periodical essay has enjoyed lasting critical approval. Samuel Johnson, himself the leading critical voice at the end of the eighteenth century, proclaimed Addison’s essays as being models of English prose style that addressed subjects of universal truth and human nature. Of course, not all readers agreed with this assessment: The narrator in Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey (1818), defended young ladies reading novels by Frances Burney as opposed to the more socially acceptable Spectator, noting that “either the matter or manner” would “disgust a young person of taste … their language, too, frequently so coarse as to give no very favorable idea of the age that could endure it.”Footnote 9 On the other hand, nineteenth-century academic commentators such as Henry Reed (1808–1854), the first American editor of William Wordsworth, applauded the ways in which Steele and Addison had turned away from the “grossness of manners and speech which had disgraced society in the years just previously … the mire of that obscenity which defiled the times of Charles the Second.”Footnote 10

In the early twentieth century, the admiration for Addison and Steele continued. Walter Graham in his history of the English periodical press enthused that while there had been periodicals published in the seventeenth century, it was “produced by inferior pens,” and that from the beginning of the eighteenth century, “the periodical was the nursery of literary genius.”Footnote 11 The online Virginia Open Anthology of Literature in English created in the twenty-first century, declares that the Spectator “set the pattern for a kind of essay writing that persists to the present day. … written in a clear and straightforward style without partisanship or professional jargon: This is a mode that is still standard in print and online journalism.”Footnote 12 In his provocatively entitled 1990 work Addison and Steele Are Dead: The English Department, Its Canon, and the Professionalization of Literary Criticism, Brian McCrea argues that it is exactly these qualities of clarity and inclusiveness in the essays’ accommodation for a “mass” audience which caused Addison and Steele to lessen in popularity in academic literary circles in the 1970s and 1980s, in favor of the more arcane and thus more in need of scholarly interpretation works by Swift and Sterne.Footnote 13

For much of the twentieth century, however, the vehicle for these essays, the eighteenth-century periodical publication itself, was a dead zone for most literary scholars. This was in part due to the difficulties in studying the original ephemeral publications prior to the creation of digital databases, but principally because with the exception of the ones written by these literary geniuses – Defoe, Addison, and Steele – periodicals were considered to be “subliterature” and not worth the effort to read.Footnote 14 By the mid-1970s, there were some literary historians who began to find the periodical itself as a genre of more interest; James Tierney pointed out that “curious indeed is a situation where many who have made the eighteenth century their life’s study have never examined more than a pittance of what the contemporary British was actually reading.”Footnote 15 In particular, the Spectator again became significant, not this time for its elegant prose style, but as part of the mechanism Jürgen Habermas argued it helped to create, a “bourgeois public sphere” through the cultivation of public opinion and the formation of good taste.Footnote 16 Commentators such as Timothy Dykstal and Erin Mackie subsequently pointed to the ways in which the contents of popular periodicals such as the Spectator and the Tatler chronicle a society transitioning into a bourgeois, capitalist society whose increasing urban middleclass readership had a seemingly insatiable desire for fashionable consumer products, especially those produced from England’s expanding colonial spaces.Footnote 17 In the 1980s, the bold claim was made that historians viewed periodicals as “an important source of insight into the early development of modern society in the West.”Footnote 18 As J. A. Downie noted in the late 1980s, for “the ideological critic, the periodical essay can truly be said to be a happy hunting ground.”Footnote 19

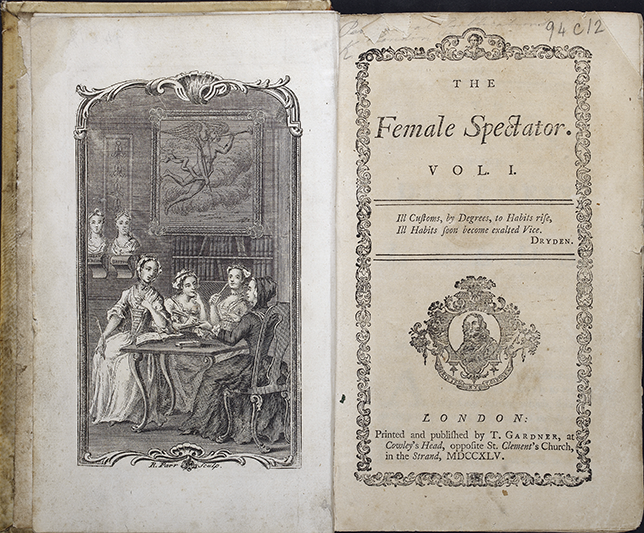

Presently, when we read or teach eighteenth-century periodical essays in our classrooms, regardless of whether we consider them to be exemplars of English prose style or windows into eighteenth-century English culture, we encounter them first as important literary texts worthy of being enshrined in internationally sold anthologies for the teaching of English literature. The tenth edition of one of the most widely used classroom anthologies, The Norton, offers twenty-six pages in a section on the Tatler and the Spectator and eleven pages of the section on Samuel Johnson are given to the Rambler and the Idler: Addison and Steele are credited as developing “one of the most characteristic types of eighteenth-century literature, the periodical essay.”Footnote 20 The Norton likewise offers students “the grave Rambler essays, which established his reputation as a stylist and a moralist … what Johson uniquely offers us is the quality of his understanding of the human condition” (711, 712). Broadview Press’s Anthology includes as well as these authors some excerpts from the Female Tatler and the Female Spectator, and describes the periodical essay as being an important step in the development of commercial print culture that “played a prominent role in the formation of popular taste and political opinion.”Footnote 21

In the anthologies’ presentation of the periodical as a genre, care is given to make an attribution of individual essays, either to Steele or Addison, or more rarely the occasional contribution by a friend, such as the poet Alexander Pope or Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. Attention is also focused on the use of fictional first-person narrators, Isaac Bickerstaff and Mr. Spectator, as a characteristic feature of eighteenth-century satire. Samuel Johnson is represented as attaining the pinnacle of the genre but there is very little sense of the Rambler and the Idler as having originally been written for ephemeral publications, and in the case of the Idler, surrounded by other materials. By stripping the essays out from their material context, this trio of neatly packaged early periodical authors has worked well as part of a chronological anthology to represent popular eighteenth-century taste and manners as well as the development of the essay as a significant literary genre alongside the novel.

As interesting and important as the contents of these periodical essays are to understanding the socio-literary views of their times, as we shall see, this was not the way in which these essays were originally conceived and designed by its authors, nor received by their initial readers. When we explore the context in which Steele and then Addison were creating their periodicals, it becomes clear that while they were masters of the craft, they were often canny adaptors, not the inventors, of conventions from many earlier popular publications. By focusing on the content of a single element within this new genre of periodical publication, the essay, and isolating it from the context in which it was created and read, we lose the sense of the ways in which its authors engaged its original readers and the dynamic nature of this new genre, which could be interactive and multimodal.

The goal of this study is to replace the periodical essay in its original format and environment, to explore how during this formative period in the long eighteenth century, its authors and creators wove together news, entertainment, creative literary forms, and social commentary in ways not dissimilar to our contemporary digital media creators. As we shall see, early periodicals also exhibit tensions between sociability and competitive commercial strategies, which have marked the development of the internet and its media forms. We will explore how the format of the new periodicals itself draws attention to the ways in which authorship and readership were both changing in response to a developing competitive media environment, an interactive literary ecology emerging from and supported by oral, manuscript, and print practices.

In the same way that late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century readers have been migrating from older print-based technologies for writing and reading into newer internet-based digital media through what is called “remediation,” seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century innovators made strategic use of “residual” features to ease that transition from one to the other. For example, still today the “save” function in Microsoft Word is the emblem of a floppy disk, a nostalgic icon of the earlier days of desktop computing of the late twentieth century, email messages on your phone can be put into an icon of a trash can, and the symbol for “search” on most digital media is an old-fashioned magnifying glass. Readers in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century were likewise becoming accustomed to reading new forms of information and entertainment in print, and it is in earlier seventeenth-century ephemera that we find the emerging strategies for establishing an audience and maintaining readership as the media changed.

1.3 Creating an Audience: Topicality, Fake News, and Newsbooks

If you’re old enough to remember fax machines, you probably remember that pre-1999, we got most of our information from print media. But it’s 2022 … Print media isn’t dead, but more often than not, I believe digital media features are the way to go in 2022 and beyond.

TikTok is fastest growing news source for UK adults … . A quarter of US adults say they always use TikTok to get the news, with nearly half of US millennial and Gen Z adults – under-41s and under-25s, respectively – indicating the same.

Readers in the second decade of the twenty-first century in search of the news are more likely than not to turn to online, digital sources and combine reading the news with watching it being performed. The transition from printed newspapers and magazines as the conveyers of both timely news and entertaining features is still ongoing, however, as many readers still are learning different ways to acquire the news information they desire, and this also requires access to the new media platforms on the internet. Those in search of news in the seventeenth century, likewise, had to learn how to acquire and to evaluate the news they sought in a volatile and rapidly changing social culture and media environment. Prior to the English Civil War, the publication of domestic “news” was illegal and controlled through a network of censorship involving the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Star Chamber, and the Stationers’ Company.Footnote 23 At the start of the seventeenth century, James I had commented on what seemed to him the unseemly desire in his English subjects to find out about “the deepest mysteries that belong to the persons or state of kings and princes,” with “an itching in the tongues and pens” to talk and write about these topics.Footnote 24 The government traditionally made its news known through proclamations, which were printed as broadsides, averaging 1,000 copies made by the King’s printer, and then delivered to the local sheriffs by messengers to be posted in a public place in the towns.Footnote 25 The majority of the residents, however, probably learned its contents through hearing the proclamations being read aloud. Important news was also delivered orally from the pulpit: as early as the nineteenth century, the historian Thomas Babington Macaulay declared the pulpit announcements were “to a large portion of the population what the periodical press now is.”Footnote 26

There was a type of news in print which escaped the censors and was eagerly consumed by seventeenth-century English readers and their appreciative listening audiences. Along with topical ballads, pamphlets featuring “strange and terrible news” had been popular sellers since the late sixteenth century, and with the expansion of news publications in the mid-century, as Julie Sievers argues, they “played a key role in the development of the ‘news’” as an emerging concept and media form.Footnote 27 Typically, such publications featured an exciting woodcut illustration amplified by a lengthy descriptive title, such as the

True and Wonderful. A Discourse relating a strange and monstrous Serpent (or Dragon) lately discovered, and yet liuing, to the great annoyance and diuers slighters both of Men and Cattell, by his strong and uiolent poison, In Sussex two miles from Horsam, in a woods called S. Leonards Foreest, and thirtie miles from London, this present month of August. 1614.

This exciting pamphlet shows a flame breathing dragon with the prostrate bodies of a man, a woman, and a cow, and a solitary dog bravely barking at it. Such “news” was presented as verifiably true, with multiple “eye and ear witnesses” willing to confirm the details, and, as seen in the dragon of Horsam, offering a high level of specific descriptive details suggesting the care taken and the veracity of the reporting.

On the other hand, strange and terrible news pamphlets also have many of the characteristics of a timeless good story: Step-mothers are merciless, murders are unnatural, and gratifyingly, the criminals typically received “most wretched endes.” These ephemeral publications were designed to inform and entertain a wide audience, from those that purchased and read them to the audiences at home and in the tavern, to those who enjoyed the pictures and listening to the dramatic accounts. Such publications thus provided material for conversation for the whole group. The contents were not intended to be meditated on in private nor be carefully preserved but instead shared and circulated, making it a sociable form of print media, one speaking to immediate events and interests.

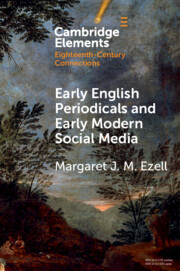

As we shall see, topicality and the use of a persuasive authorial persona found in earlier seventeenth-century pamphlets and newsbooks are characteristics of the late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century periodicals. Not only did readers want the latest information, but they also wanted it presented with a narrative voice that generated trust in its truthfulness. As the English Civil war broke out and censorship collapsed, the pamphlet producers had a different source of shocking and sensational news of the greatest interest to their readers, but often in forms and formats familiar to the readers of strange and wonderful news. The newsbooks and pamphlets that were produced by both sides of the English Civil War in the 1640s and early 1650s loudly proclaimed the accuracy and authenticity of their content, even when it clear that the account is biased, and the narrative is serving as propaganda (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Terrible and Bloudy Newes (1648).

Between 1645 and 1660, newsbooks and pamphlets were the main source of information about domestic military and domestic events for English readers, with an estimated 300 periodical publications appearing, despite attempts by the powers in charge to control their publication through ordinances. After the censorship mechanisms collapsed during the early days of the war, with an estimate that over 300 periodical publications appeared between 1645 and 1656, although like the pamphlets few of these cheap, ephemeral publications survived.Footnote 28 They were variously referred to by titles that emphasized their speedy delivery of timely information, as well as their international scope, such as “diurnals,” “gazettes,” “currants,” “mercuries,” and “corantos,” the last of which were single sheets produced in Amsterdam but printed in English which featured foreign news. While “Gazetta,” is derived from Italian gossip sheets published in Venice in the mid-sixteenth century, names such as “mercurius” emphasized the importance and the veracity of the contents, being transmitted as it were by Mercury, the messenger for the classical gods.

Both forms, the pamphlet and the newsbook, were early forms of journalism that catered to the interests and literacy levels of the broadest possible audience. As one historian observed, modern readers “need not assume that the purpose of this early journalistic effort was to spread the truth. … Newsbooks could not help being informative,” he observed, “but the truth of their content was not as important as that there be something for sale every Monday.”Footnote 29 Using woodcut illustrations as well as dramatic dialogues and poetry to capture their audiences, their announced function was to inform readers and listeners of all the important political, military, and religious news of the day; they also served as political propaganda, incorporating popular ballads and sensational fictions in a witty and reader-oriented style. Sold by street vendors and “Mercury Women,” who also sold ballads sheets typically for a penny, these publications like the earlier “wonders” pamphlets were also able to be enjoyed by those who heard them being read aloud in public spaces.Footnote 30

This new print genre, however, generated anxieties that still mark readers’ responses to topical media today. Since the 1930s, there has been increasing concern and anxiety in western European societies that the “news” has become merely “entertainment.” However, media critics observe that “the line between news and entertainment is inherently blurred and contestable and never fully maps the boundaries between politically relevant and politically irrelevant media forms”: instead, “it was only the regulations, institutions, norms, and practices that came to define the broadcast news media regime that made such distinctions seem natural.”Footnote 31 Whether it is called “soft” news or, in the 2020s, “fake news,” the practice of mixing entertainment with news in popular mainstream media served to keep audiences engaged and eager for more.

Marchamont Needham was a leading figure in the evolution of newsbooks. Regardless of which side he was writing for at the time, he believed in mixing information and news with entertainment. Writing in 1649 for the royalist Mercurius Pragmaticus, Nedham explained the purpose of including verse in his news accounts: poetry serves “to tickle and charme the more vulgar phant’sie, who little regard Truths in a grave and serious garb … yet I would have you know, in the midst of jest I am much in earnest.”Footnote 32 In 1650, now writing for Parliament, he shows a shrewd awareness of how to amplify his voice not dissimilar to a Twitter or Instagram poster seeking to attract followers who will share his content: “The designe of this Pamphlett being to undeceive the People,” he explained, “it must be written in a Jocular way, or else it will never bee cryed up.”Footnote 33 Likewise, John Hall writing for Parliament in 1648 Mercurious Britanica Alive Again declares that the newsbook which opens with four stanzas of verse only does so because readers expect it: “thus do we according to the solemnity of a Pamphlet begin with verse; for it we should not retain the accustomed ceremonies of abusing the people, we should render them useless, and loose our labour.”Footnote 34 Commenting on the audience’s expectations of more than just a list of the events of the day, he makes the point that “how many Ballads would sell without a formal wood cut? These general complyances must needs to observed, or else the people out of the rate of their madnesse will not be brought to parley.”

Joad Raymond has suggested that the preference for poetry as the medium for the royalists writers reached its height in Mercurious Melancholicus which not only featured the news in verse, but also branched out into satiric playlets with titles such as Craftie Cromwell (1648) and Mistris Parliament Brought to Bed of a Monstrous Childe of Reformation (1648).Footnote 35 Describing “poetry as integral to its identity,” Raymond suggests that Mercurious Melancholicus from its start was a “literary” newsbook; other royalist periodicals including Mercurious Elencticus and Pragmaticus followed its lead. They, too, were formatted by opening with poems consisting of four quatrains in a ballad format to set up the contents of the editorial commentary that followed, and they proudly boast of the superiority of royalist poets and their followers.Footnote 36 In addition to reporting events, such publications also offered reflections on the state of the nation, urging royalist readers to remain loyal and encouraging those who were becoming disenchanted with Parliament to embrace their points of view.

Even with the spread of printed news with its entertaining woodcuts and verses, commercial handwritten newsletters remained competitive, offering its subscribers information such as reproducing parliamentary speeches which its printed counterparts could not. During this period, Henry Muddiman and Sir Joseph Williamson oversaw the production of both printed newsbooks and manuscript newsletters. As Rachael Scarborough King has noted, even though the handwritten newsletters were more expensive than a printed newsbook, costing from £5 to £20 per year as opposed to the printed pamphlet at 1d per issue, nevertheless the circulation of the scribal ones rivaled those of the printed versions.Footnote 37 The handwritten newsletter was a compilation of individual news items sent by letters from multiple sources, which was mailed from London to the subscriber, who was often living outside of London. These handwritten accounts were obtained by subscription and apparently enjoyed a significant readership outside the immediate environs of London.

The scribal newsletters retained residual features of private correspondence, creating an aura of exclusivity and a social connection between the reader and the imagined “author.” Rather than appealing to its readers by opening with amusing verses, the handwritten versions were formatted in the form of a letter, typically opening with the salutation, “Sir,” which some literary historians have compared to creating a more personal relationship with the reader, “giving the recipient the pleasant feeling that he was reading his own private correspondence.”Footnote 38 We are fortunate that they were sufficiently valued by their readers that some were kept intact and collected in a set, providing invaluable information to subsequent generations of historians, and also suggesting how in the future printed ephemera might also be viewed as collectible by its readers.Footnote 39

Whether handwritten or printed, the relationship between the creator of the newsletter or newsbook and the reader was different from that of the official proclamation, printed or announced. It is in the creation of this illusion of familiarity, of social connection, which resonates with our contemporary digital media experiences, especially in who (or what) we trust to give us news – who do we follow online? Unlike creating a news bulletin or a simple commercial, the hopeful social media influencer, for example, is advised present “content” in an attractive package, one that “gives the impression that the followers are learning more about a creator, and … build this relationship.”Footnote 40 Essential to an influencer’s success, apparently, is creating this friendly virtual relationship, cultivating the audience’s sense of familiarity to create trust and loyalty. It is the prevalence of this illusion of friendship which will be explored in Section 2 “Sociable Periodicals, 1690s–1700s” on periodicals devoted primarily to entertainment reading. In these “sociable periodicals,” the reader is invited to become part of a supposedly select audience who not only support the media “platform” by acquiring all of the issues and collecting it in multiple formats, but also create much of its contents.

2 Sociable Periodicals, 1690s–1700s: The Royal Society of London’s Philosophical Transactions, John Dunton’s the Athenian Mercury, and Peter Motteux’s, the Gentleman’s Journal

The concept of the active audience, so controversial two decades ago, is now taken for granted by everyone involved in and around the media industry.

After the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, writers and publishers were eager to satisfy the expanding reading public’s appetite for topical news combined with entertainment, a combination to which readers had become accustomed through the popular mid-century newsbooks and pamphlets. Continuing many of the practices established by those earlier periodicals, these new publications also shared several formal characteristics that helped to establish a bond with their readers: For example, they typically featured a standard title page format that was dated, with numbered issues and volumes, and which contained information about the regular publishing days during the week and from whence the publications could be obtained and advertising left. These features highlight that the contents were part of an ongoing narrative sequence, a serial publication rather than a single title. In contrast to purchasing an individual sensational pamphlet, these serial publications, although ephemeral in nature, sought to engage their readers’ attentions over the long term, and to build a stable, loyal readership for that particular title. Much like modern media marketing, the periodicals employed various strategies to encourage and entice their readers to look forward to each new issue and other literary “products” associated with that title. In addition, these new style periodicals encouraged the active participation of their readers, to create content for the periodical for the pleasure of the association rather than any financial or business inducement.

2.1 Publishing Serial Periodicals and Topical News

The serial nature of these publications was both a challenge for the writers and publishers and a marketing advantage. It challenged the booksellers to produce their periodicals on schedule, with informative, entertaining content. On the other hand, it enabled the publishers to point readers to content in previous issues, an interactive feature that relied on the reader to have been engaged with the periodical over a span of time and to be willing to reread this supposedly disposable ephemeral work. It also creates the conditions under which the reader can anticipate the paper being worth while holding on to over time and rereading. To promote that feature, as we will see with the bookseller John Dunton, single sheet publications could be packaged later as collected bound volumes, with extra features such as indexes and companion volumes – and the ephemeral is transformed into the collectible.

Book historians grappling with the large question of what is “print culture” and how can it be recognized have pointed to this element of seriality as being a central factor in making the claim that such a culture existed. “There is a strong argument to be made,” Jason McElligott and Eve Patten suggest, “that it is impossible to conceive of a print culture in any society without the presence of serial publication: corantoes, newsbooks, newspapers, magazines, or literary journals.”Footnote 42 Serial publications not only demonstrate that the technical ability existed to produce texts reliably in a fixed pattern of publication but they also extended booksellers’ ability to attract buyers on a regular, predictable schedule: “The development of seriality was obviously a function of living in interesting times,” they observe, “but it was also a striking technical achievement and a sophisticated commercial strategy” (6). As we shall see, it also created new avenues for sales, both through including advertisements and what today we would refer to as “spin-off” merchandising, or just “merch.”

What I am referring to in this section as “sociable” periodicals had a different style of relationship with their readers, in contrast to that of the also newly forming genre of the newspaper. For example, during this period, the London Gazette stakes its claim to be the oldest continuously printed newspaper in Britain. It first appeared under the title the Oxford Gazette on November 7, 1665 when the court had relocated to Oxford attempting to escape the Great Plague decimating London. On the court’s return, it was rechristened the London Gazette on February 5, 1666, with the seasoned journalist Henry Muddiman overseeing its publication until 1688.Footnote 43 During this time, Muddiman also continued his very successful manuscript subscription newsletter, mentioned in the previous section, which had the advantage of being able to report on parliamentary proceedings, which was once again forbidden to appear in printed accounts. Initially published as a single sheet with two columns on each side, London Gazette subscribers were assured every issue that its contents were “Published by Authority.”

The contents of the Gazette were derived from multiple sources both international and domestic. Readers of the February 5, 1665 issue learned from a dispatch from Falmouth dated January 27 that a ship of eighty tons from Dublin filled with tallow and hides, bound for Cadiz, “proves so leaky” that the Captain was obliged to cut short the voyage and sell the goods and the ship itself. From Rome, we read an account dated January 16 of how the Pope fearing that Christendom is rushing into war asked the Cardinals to join with him to pray that war would be avoided. The account of this pious action is combined with gossip that the French representative to the Vatican had been strongly offended by the performance there by “a company of Ordinary Players” of a play which he viewed as mocking the French and he had “complained to the Popes [sic] Nephew of this designed insolence and National dishounour.”Footnote 44 The Gazette, like the manuscript newsletters that had proceeded them, was dependent on the steady flow of letters from a network of business and diplomatic correspondence for its contents.

2.2 The Royal Society and the Philosophical Transactions

While the London Gazette became established as the source of reliable, government authorized information about shipping, diplomatic events, and military matters, other contemporary periodicals focused elsewhere. Through the publication of its Philosophical Transactions starting in 1665, the newly formed Royal Society of London kept its members informed of scientific developments in London and the provinces, on the continent, and in the Americas. Its full title gives some sense of its original scope and appeal: Philosophical Transactions: Giving some Accompt of the Present Undertakings, Studies and Labours of the Ingenious in Many Considerable Parts of the World.

Initially, its contents reflected the scientific interests and international connections of the first secretary of the Royal Society, Henry Oldenburg. Oldenburg had informed the eminent scientist Robert Boyle that he intended to establish a manuscript subscription newsletter devoted to science, but perhaps in response to the appearance of the French print periodical, the Journal des Scavans, he instead developed a monthly printed publication which sold for a shilling a copy.Footnote 45 Oldenburg was the compiler, editor, and also a contributor. In the “Introduction” to the first issue, he explains that “there is nothing more necessary for promoting the improvements of Philosophical Matters, than the communicating to such as apply their Studies and Endeavours that way, such things as are discovered or put in practice by others”; he concluded that “it is therefore thought fit to employ the Press,” as the best means of sharing discoveries both in England and in “other parts of the World.”Footnote 46

The table of contents of this first issue reflects the wide range of topics to be found inside and the ways in which content came to Oldenburg: “A Spot in one of the Belts of Jupiter,” was the discovery of Robert Hook, who did “some months since, intimate to a friend of his, that he had, with an excellent twelve foot Telescope, observed, some days before, he than [sic] spoke of it (videl. On the nineth of May, 1664, about 9 of the clock at night) a small Spot on the biggest of the 3 obscure Belts of Jupiter.”Footnote 47 A lengthy synopsis of a publication from France followed, sent by its author, the French astronomer Adrian Auzout, on the motion of a recent comet. This was followed by a list of experiments being conducted by Robert Boyle; Boyle additionally communicated news of “a very odd Monstrous Calf,” communicated to him in a letter from Mr. David Thomas from Hampshire.Footnote 48 Finally, an anonymous “understanding and hardy Sea-man,” had contributed an eye-witness account of whale fishing in the West Indies. Clearly, the journal offered something for every interest remotely connected to the new mode of science, very broadly defined. There is no indication that any of the contributors received or expected payment.

For the rest of the seventeenth century and the first half of the eighteenth, the contents of The Philosophical Transactions were determined the editor alone, who was typically the Secretary of the Society. By 1693 when John Dunton’s the Athenian Mercury, was well established, Richard Waller had the editorship of the Transactions. Issue 196 contained a posthumous account of Boyle’s method for making Phosphorus, an exchange in Latin by John Wallis, extracts of two letters from the continental scientist Anthonie van Leeuwenhoek to Dr. Gale, Waller’s own description and anatomical drawings based on his dissection of a rat, and a list of books recently published. This practice of including a medley of topics and accounts at the discretion of the Secretary alone lasted until 1752, when the financial side of the periodical was taken over by the Society itself and the process for submitting materials became regularized, with a committee of twenty-one Society members formed to decide what merited publication.

2.3 John Dunton, the Athenian Mercury, and the Ladies Mercury

By the 1690s, other periodicals began to appear that offered the general reader the chance to engage with a variety of topics ranging from theology to astronomy and literary pursuits. The publisher and bookseller John Dunton previously was known to Restoration scholars primarily as a struggling, quarrelsome bookseller who published his autobiography, The Life and Errors of John Dunton (1705). In the last few decades, however, he has become increasingly studied for his successful development of the “question-answer” periodical, the Athenian Mercury, and in particular his attempts to engage women readers, resulting in the Ladies’ Mercury (1693).Footnote 49 Helen Berry has made a compelling case for the Athenian Mercury as “one of the most original and culturally-significant works to have emerged from the popular press” in the late Stuart period, indeed the forerunner of “what we would now recognize as an embryonic mass media” (6). In addition, E. J. Clery views Dunton as “the greatest early innovator of the discourse of feminization.”Footnote 50

Dunton’s success and his impact with this journal came from an original idea to generate content for his paper: While manuscript newsletters had encouraged readers also to be correspondents and to contribute information to be circulated, Dunton invited “All Persons whosoever” to send “any Questions that their own Satisfaction or curiosity shall prompt ‘em to,” and, as long as the questions were not malicious, obscene, or promoting atheism, they would be answered by a sociable club of anonymous intellectuals. In his autobiography, he recorded how the idea for this new type of periodical came to him as he was walking home one evening, a publication whose content relied on questions on an astonishing range of topics submitted by its readers. Dunton attributes the inspiration to the Bible, Acts 17.21: “For all the Athenians and strangers which were there spent their time in nothing else, but either to tell, or to hear some new thing.” The title of the periodical was originally the Athenian Gazette, which highlighted its claims to veracity and topicality. However, Dunton records in his memoir that “to oblige Authority,” the title was changed to the Athenian Mercury; it is also possible that Dunton perhaps realized this association with the government was a limitation on the potential of the journal rather than an asset.

The design, as laid out in the first issue, was ambitious by any standard. It was supposed

to satisfy all ingenious and curious Enquirers into Speculations, Divine, Moral and Natural, &c and to remove those Difficulties and Dissatisfactions, that shame or fear of appearing ridiculous by asking Questions, may cause several Persons to labour under, who now have opportunities of being resolv’d in any Question without knowing their Informer.Footnote 51

Because Dunton had imagined the periodical to be the platform for a type of learned society or club, whose interests encompassed “the whole compass of Learning,” and because it was to appear twice weekly, as Dunton noted, it “required dispatch” in assembling his experts.Footnote 52 “The Athenian Society had their first meeting in my brain,” he confesses.Footnote 53 To answer the questions posed, he initially called on for help from his associate the mathematician and schoolmaster Richard Sault; it would appear that in launching the new project that Dunton and Sault composed both the questions and the answers for the first two issues. Questions in these initial issues, which presumably would inspire readers to submit their own for future ones, included “whether the Torments of the damn’d are visible to the Saints in Heaven? & vice versa,” “Whether ‘tis lawful for a Man to beat this Wife?” “What is the Cause of Dreams?” and “Why does the Needle in the Sea Compass always turn to the North?” After the first few issues, the ingenious Mr. Sault was joined by Dunton’s brother-in-law the Reverend Samuel Wesley (an Anglican minister and poet and the father of the future founders of Methodism, John and Charles Wesley), and occasionally by “Dr. Norris,” identified variously as either the physician Edward Norris, or Dr. John Norris, the poet and philosopher associated with the Cambridge Platonist.Footnote 54

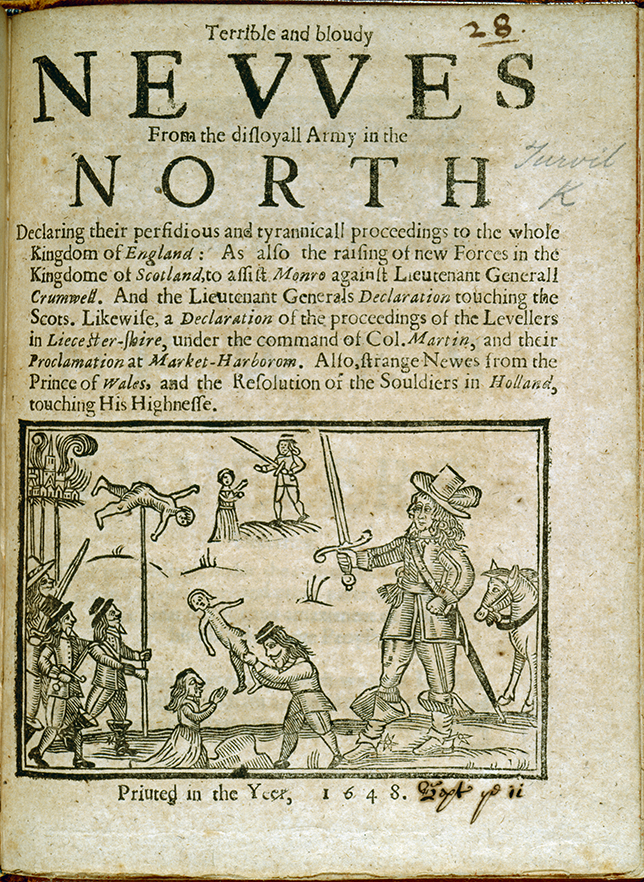

Berry and Shevelow have interpreted the readership of the Athenian Mercury once it was established as being composed of the “middling sort” of reader; commenting on the frontispiece in Charles Gildon’s History of the Athenian Society (1692; Figure 2), Berry notes that illustration, “the most striking aspect is its social diversity and inclusion of men and women of all ranks presenting questions to the Athenian Society.”Footnote 55 It is significant to note that in addition to the “Athenians” being anonymous experts, the readers who submitted questions also retained their anonymity, each question being presented as a numbered query. As Dunton noted, this protected the reader from being revealed as either poorly educated or being young and naïve; it also gave license to ask about a seemingly unlimited range of topics.

Figure 2. Emblem of the Athenian Society (1692).

The success of the Athenian Mercury was clearly its format and the use of a new method of textual transmission to create content. Instead of relying on government dispatches or shipping accounts for its contents, the Athenian Mercury instead relied upon its readers to suggest questions by sending them in letters to Dunton in London through the newly established Penny Post. The Advertisement at the end of the first issue reiterates how readers can become involved with this ingenious design to promote human knowledge.

All Persons whosoever may be resolved gratis in any Questions that their own Satisfaction or curiosity shall prompt ‘em to, if they send their Questions [in] a Penny Post letter to Mr. Smith at his Coffee-house at Stocks-Market in the Poultry, where orders are given for the reception of such Letters, and care shall be taken for their Resolution by the next weekly paper.

Writing in hindsight about the early response to the call for questions from readers, Dunton records that “the Project being surprising and unthought of, we were immediately overloaded with Letters; and sometimes I have found several hundreds for me at Mr. Smith’s Coffee-house in Stocks Market, where we usually met to consult matters.”Footnote 56

The Penny Post had been established in 1680 by William Dockwra and taken over by the government in 1682; by the time of the Athenian Mercury in the early 1690s, it would have been a well-established and familiar mode of communication.Footnote 57 This new form of textual technology made London publishers and booksellers such as Dunton accessible to a wide range of readers outside London proper; as the invitation to “all people” suggests, individuals such as genteel young ladies who might never enter a London coffee house to read the papers or present their writings in person now had an inexpensive way of accessing the London publishing market and the booksellers had an apparently unlimited supply of free content makers.Footnote 58

Indeed, so many women readers responded enthusiastically to the new format and publishing venue that for four weeks in spring of 1693, Dunton produced the spin-off, the Ladies Mercury separately.Footnote 59 The first issue opens with an address “To the Athenians,” assuring the gentlemen that “Your Worth and Learning to which we must pay a just Esteem, is the occasion of this Address, in which we desire you to excuse this Undertaking, as not at all intended to encbroach [sic] upon your Athenian Province.”Footnote 60 Continuing in a deferential strain, the presumably female speaker promises that the “fair and larger Field; the Examination of Learning, Nature, Arts, Sciences, and indeed the whole World” will remain a masculine province while “We are for sitting down with Martha’s humbler part, a little homely Cookery, the dishing up a small Treat of Love, &c.”

In contrast to the regular issues of the Athenian Mercury, where the questions are presented merely as numbered queries, those featured in the Ladies Mercury contextualize the question with information about the situation of the writer. This narration results in much longer questions and also much more complicated answers that offer advice as much as information. It also supports the voice of a sophisticated female responder, or rather the corporate voice of a “female society,” which appears not to be shocked by even the most complex emotional entanglements and potentially compromising situations.

The very first question, for example, is posed by a “very young woman,” who had the misfortune to be seduced by “a lewd and infamous Trifler, with whom I secretly continued this vile and unhappy Conversation for near a Twelve Month together.” Her dilemma, however, is not how to negotiate her way out of social ruin from this premartial affair but how to assuage her guilty conscience when she enters into marriage with “the kindest and most passionate of men,” who is besotted with her and she with him: “The more I dote on him, and he the like on me, a rueful Remembrance makes me consider my self so much the more unworthy of him.” She declares that she is “haunted” by “what Delusion and Pollution I brought to his Bed; what practiced Cheats and Impostures have I used, all my affected feigned Innocence … practiced even the vilest of Arts in his very Bridal Night Joys, being in that dearest Scene the highest of Counterfeits.” The Answer urges her to put her sin against Heaven behind her and “when that Honourable Lover afterwards addres’d himself, no Obligation even of the most Rigid Laws compel’d you to be your own Accuser,” and it was not up to her to point out his mistake in believing her a virgin. As “your sin lyes concealed from the world,” no “infamy” is attached to their union, and pragmatically, she should “exert thy tenderest, kindest, duteous, softest Love in all the opening, blooming, ravishing, melting fragrance, that the whole Paradise of Truth and Faith, with all its endless boundless Joys can give him,” and keep her repentance to herself.

As the Advertisement made at the end of the first number makes clear, both “Ladies and Gentlemen” are asked to send their questions to “the Latin-Coffee House in Ave-Mary Lane.” The second question in the first issue comes from a young man, not quite of age yet, who is making “honourable Love to a young and Beautiful Lady.” He describes in some detail the nature of this wooing and its “Innocent Dalliances,” which involve passionate, reciprocal kisses and embraces, firing his imaginings of “the Raptures of Possession.” His concern is whether such thoughts and acts are sinful, although he hopes that being “a Good Christian and a Good Lover are things not incompatible.” This query required only a brief assurance that if a marriage followed, no sin was involved.

The second issue published Sunday a week later on March 6, appears to have built upon the favorable response to the first, for its advertisement announces that questions on love are still being solicited and that the third issue will be published on the following Friday. It noted that “the Ladies Society” sought to provide answers “with all the Zeal and Softness becoming the Sex.”Footnote 61 The Ladies Mercury, in fact, had only four issues, but were highly influential in shaping imitators seeking to enter this entertaining new market, which offered the reader a combination of scandal and probity, romantic scenarios, and supposedly a peek behind the curtains of respectability of one’s fellow readers, familiar today in personal advice columns.Footnote 62 Although the advice column is typically described as an invention of mid-nineteenth-century newspaper proprietors, the argument has also been made that it was a feature of eighteenth-century American periodicals as well. Lisa Logan points to the popularity of the “Dear Matron” column which appeared in the Boston periodical The Gentleman and Lady’s Town and Country Magazine: or, Repository of Instruction and Entertainment (1784–1785) which features questions about topics such as bigamy and adultery answered by the “worldly-wise wit of a respected (and respectable) woman.”Footnote 63 This desire, however, to have advice as well as to preserve one’s anonymity, tracks neatly from Dunton in the previous century through current periodicals.

In addition to devoting individual issues to questions posed and supposedly answered by women, Dunton also began offering special issues featuring verse. In a December issue in 1691, a reader wondered “Is there ever a Poet among the Athenian Society, and supposed a Question shou’d be sent in Verse, shou’d it be anser’d in the same?”Footnote 64 The journal had published individual poems prior to this, but in January 1692/93 the first “poetical mercury” appeared. As Barbara Benedict has noted over the latter part of the seventeenth and beginning of the eighteenth centuries, “periodicals thus became a new venue for publication by part-time writers, amateur critics, and authors in training.”Footnote 65 The young Jonathan Swift, writing from his position as Secretary to Sir William Temple in 1691 sent his “Ode to the Athenian Society,” perhaps his first published poem, to Dunton, asking if it could be printed in the supplement of the Fifth Volume, observing that “since every Body pretends to trouble you with their Follies, I thought I might claim the Priviledge [sic] of an English-man, and put in my share among the rest,” and that “before its seeing the World, I submit it wholly to the Correction of your Pens.”Footnote 66 Temple, Dunton notes in his Life and Errors, was “a man of clear judgment and wonderful penetration” and “pleased to honour me with frequent Letters and questions, very curious and uncommon,” while he characterizes Swift only as “a Country Gentleman.”Footnote 67

Perhaps the most celebrated poet who contributed to the Athenian Mercury was the young Elizabeth Singer Rowe (1674–1737), not long out of boarding school. Rowe would go on to achieve literary fame during her lifetime for her poetry and her prose fiction.Footnote 68 The young woman had by 1694 become, in Katheryn King’s words, “the leading contributor of verse to the Mercury.” King speculates that she had begun in 1691 by sending “poetically inclined” queries; her first known poem was printed October 21, 1693, “Habbakkuk,” which even though it was introduced as being “somewhat uncorrect,” was nevertheless published “for the Honour of her Sex” – the Athenians responded enthusiastically in the poem which followed it, “How vast a Genius sparkles in each Line!”Footnote 69 The full poem later appeared in Rowe’s Poems on Several Occasions Written by Philomela (1696), which was also published by Dunton, who crowned her “the Pindarick Lady.” Heidi Lauden suggests that following her contributions to the Athenian Mercury, one can “see how she consciously carves out a space for herself in the public domain and craft, with the help of the Athenians, a poetic identity that becomes a critical component to the periodical and to her own future success.”Footnote 70

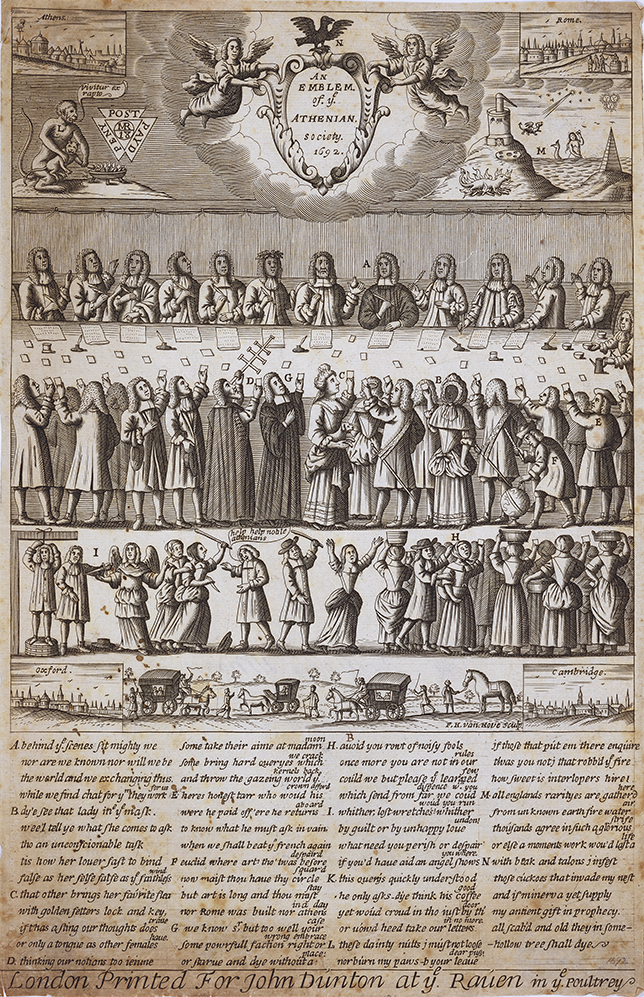

There is no evidence that Dunton offered payment to those readers such as Swift and Rowe who contributed to the content of the Athenian Mercury, nor indeed that they expected any. There is no doubt, however, that the periodical was a successful commercial venture for Dunton. The Athenian publications were remarkably popular for many years, typically appearing in single sheets twice weekly between March 1691 and 1697 (Figure 3). Such was their appeal, Dunton also collected the individual papers and bound them into volumes, each composed of thirty issues, which Dunton records “swelled at least to Twenty Volumes folio” and which, like the single sheets, could be purchased at his shop. As his biographer Gilbert McEwen noted, such was his confidence in the sales of the new periodical that Dunton in the second issue of the fledging paper, he had already envisioned the spin-off product which would include both a preface and an index, both of which McEwen describes as “innovations” for English periodicals.Footnote 71 Dunton also promised the reader of his memoirs that they would also be able to purchase Athenian Mercury merch, “a choice Collection of the most valuable Questions and Answers, in Three Volumes.”Footnote 72 Dunton also produced multiple supplements which were bound into the volumes offering the purchaser extra value: The first supplement contained information about “transactions and experiments of the Forreign Virtuoso’s [sic],” and an account of “most of the considerable Books Printed in all Languages; and of the Quality of the Author, if known,” in addition to translations of excerpts from learned journals such as the Paris Journal des Scavans and “in the New Book Entituled, Entretiens Seriuses & Galantes, &c.”Footnote 73 Towards the end of his career, Dunton attempted to revive the brand, publishing four volumes of yet more questions and answers under the title of The Athenian Oracle (1703–1710).

Figure 3. The Athenian Mercury (1691).

The Athenian model of soliciting content in terms of questions, puzzles, and poetry was so successful, it soon attracted imitators, adapters, and satirists. The Grub Street writer Tom Brown (1662–1704) did a satirical counterpart, initially called the London Mercury, which quickly became Lacedemonian Mercury in February 1692/93. Brown, who earned his precarious living exploiting whatever genre was popular at the moment, deliberately tied his publication to Dunton’s periodical by titling after Athens’ ancient rival and enemy, the Lacedemonians (Spartans). Initially assisted in this effort by his friends Charles Gildon and William Pate, Brown released the first issue on Monday February 1, and brazenly announced that would it answer all questions sent to its preferred coffee house, Welsh’s, near Temple Bar. As commentators have noticed, being published on Mondays and Friday, it thus could beat the Athenian Mercury’s responses which were printed on Tuesdays and Saturdays.Footnote 74 The University educated Brown ruthlessly skewered what he considered to be the overly pedantic and serious tone of Dunton’s periodical, especially as it busied “the Press with impertinent Questions of Apprentices and Chamber-maids,” and, rather than tackling serious intellectual issues of history and philosophy, “they have everlastingly stuff’d their Papers with Receipts for Fleas &c and such like.”Footnote 75 Continuing this unflattering attention given to Dunton’s periodical, Elkanah Settle, the dramatist and City Poet in charge of writing the annual pageants celebrating London’s prestige and prosperity, published in 1693 The New Athenian Comedy. In it, Settle mocks the pseudointellectualism of “coffee-house culture” and the social status of its members; Settle’s characters underscore Brown’s mockery of the Athenians’ membership, with names such as Obabia Grub, the leader, and Dorothy Tickleteat, a milkmaid.

2.4 Peter Motteaux and the Gentleman’s Journal

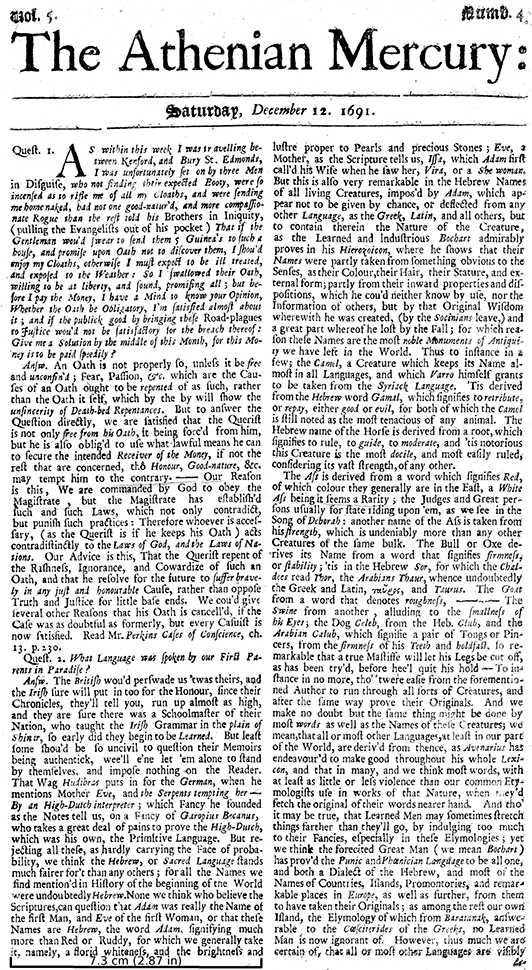

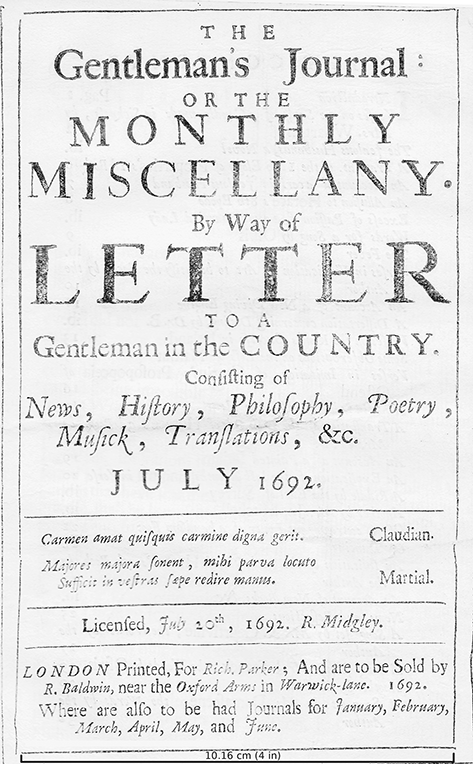

A year after Dunton launched his periodical, the professional writer Peter Anthony Motteaux (1663–1718) started the Gentleman’s Journal, which enjoyed thirty-three issues between 1692–1694. Born Pierre-Antoine Le Motteux in 1663 in Rouen, the young Huguenot had fled France in 1685 after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes and joined a large French refugee population in London. Although he is probably best known today as the translator of both Rabelais and Cervantes and whose death was the subject of a notorious murder trial, Motteux’s pursued a varied career as a shopkeeper, auctioneer, dramatist, and librettist during the last decade of the seventeenth century.Footnote 76 Motteux’s was a monthly periodical, which instead of being the front and back of a single-sheet, was a quarto pamphlet averaging around thirty pages (Figure 4). This expanded format offered the reader a variety of short reading entertainments, including verse by popular contemporary London poets such as the soon to be poet Laureate Nathum Tate, Aphra Behn, Matthew Prior, John Phillips, the ever-busy Charles Gildon, and the dramatist William Congreve. In addition, it also featured accounts of new plays, information about national events and personalities, such as the Duke of Bavaria being made the Governor of Spanish Netherlands, as well as new songs, complete with musical scores.

Figure 4. The Gentleman’s Journal (1692).

Motteux dedicated the first issue to the Earl of Devonshire, announcing the desire the little journal should “attend your Lordship when you enter into your Closet, to disengage your Thoughts from the daily pressure of Business.”Footnote 77 While its title page describes the contents of consisting of “News, History, Philosophy, Poetry, Musick, Translations, &c,” poetry, songs, and translation dominate the pages, not news. Told in the form of a familiar letter from a Londoner to his friend in the countryside, the Gentleman’s Journal breaks with this narrative when in the next issue, it opens with an advertisement preceding the table of contents stating that the author has had so many letters commenting on the first issue that he cannot answer them all, but he promises to insert his readers’ observations and contributions as long as they do not libel any one or speak against “Religion, or good Manners.”Footnote 78 The narrator opens this “letter” to his friend observing that the “Generality of Readers lik’d the Design of the Book” and that several “ingenious Pieces … have been given me,” such as the poem which follows that is attributed to the fashionable Matthew Prior (1664–1721) (“Howe’r; ‘tis well, that whilst Mankind,/ Thro’ Fates Fantastick Mazes errs”), and an imitation of one of Horace’s Odes, “given me by a Friend” (5–6, 9). The appeal to the reader to become a contributor, to send by post their or their ingenious friends’ poems, enigmas, and fictions, as I have argued elsewhere, is a step further than Dunton’s request for queries: by urging his readers to become active content makers for his periodical publication, Motteux is essentially commercializing the traditional practice of coterie or social authorship, with its circulating and curating social network’s manuscript pieces.Footnote 79

As critics have noted, while Dunton was indeed in the business of books, he was not himself primarily a professional writer, as was Motteux. Walter Graham in his early study of the literary periodical noted that Motteux was, “a man of letters [and] for the first time the literary periodical as in the hands of professional writers.”Footnote 80 Motteux’s literary skills were wide ranging – he not only translated Cervantes and Rabelais, but he also wrote prologues and epilogues for multiple dramatists including George Farquhar, John Vanbrugh, Mary Pix, and songs for Aphra Behn’s comedy The Younger Brother. He also had several of his own tragedies, comedies, and operas performed. He achieved a measure of commercial success in the most popular Restoration literary enterprises, even if his biographer Robert Cunningham described him as having “versatility” rather than brilliance.Footnote 81 Pragmatically, Motteux knew what would sell; to meet this demand, he skillfully attracted a group of amateur contributors as well as calling on his professional literary acquaintances to create the contents. As I argued elsewhere, Motteux was able to secure and sustain the Gentleman’s Journal for three years in part through his recognizing and exploiting the characteristics of coterie, social authorship practices within a commercial framework, not unlike today’s participatory culture.Footnote 82

Some of the elements that characterized earlier social or coterie literary exchanges included the use of pen names, the popularity of response pieces, and the feeling of community or familiarity among the writers and readers. Motteux used a direct form of appeal: The “Advertisement” below the table of contents of the Volume 2, issue 5 May, 1693 desired that “the Ingenious are desir’d to send such Pieces in Verse or Prose that may properly be inserted in this Miscellany.” These can be left at the shops of either of the booksellers mentioned on the title page, Richard Parker at the Unicorn under the Piazza at the Royal Exchange or Robert Baldwin’s near the Oxford Arms in Warwick-lane. Parker was a successful young bookseller in the fashionable Royal Exchange, while Baldwin, along with his wife Anne (who continued his business after his death in 1698 and published the Female Tatler to be discussed in the next section), was among the best known of the London printers and bookbinders of this decade, publishing not only political pamphlets, satires, and periodicals but also plays and romances. In addition, those who wished to contribute but did not live in near the two booksellers or in London, could address a letter to the “Author” of the Gentleman’s Journal at the Black-Boy Coffee-house in Ave-Maria Lane, “not forgetting to discharge the Postage.”

Among the contributions published in the May 1692 issue were a satire, “they came to me out of the Country … I am not told who is their Author,” the correct solution to the enigma poem in the previous issue answered in verse by Mr. Jon. Olt, which was also correctly solved by “Aurelia,” T. S., T. Powell, and “S. Strephon.”Footnote 83 A new enigma poem was sent to Motteux by “Philander” in “Edenburgh”: “An unborn Queen of Sweets and Beauties I,/ Still blushing, and still smiling, live and die./ In richest Robes of purest Light, I shine;/ And all my happy Nourishment’s divine.” The answer as revealed in the June issue is a rose and it inspired Mr. Patrick Johnson to address verses “To the Ladies on the Enigma for May”: “A Darker Riddle, Ladies, ne’er you knew/ ‘Tis hard to guess what’s meant, a Rose, or You.” This type of literary game offered readers the chance to participate in a literary network outside their immediate family and friends.

Relying on the ingenious readers for content, however, could be unpredictable. In March of 1692, Motteux informs his fictious acquaintance in the country that he is running out of materials to be included, laboring as he says under the “necessity there is of a constant Supply of Ingenious Prose and Poetry, to carry on the Undertaking.”Footnote 84 “I hope, Sir,” Motteux observes, that “the Ingenious of both Sexes will maturely consider of the Exigency of the Case. For tho’ I have had several very fine things sent Me: yet I shall have occasion for more, and some things, as I declared it in my last Month’s Advertisement, tho’ never so ingenious, I cannot insert.” The content of Motteux’s Journal was, like the initial form of the Philosophical Transactions, largely dependent on what the editor could persuade his network of friends and correspondents to contribute, balanced out by his own works; the September 1692 and the July 1693 issues were entirely Motteux’s own work.Footnote 85

The Gentleman’s Journal, more than the Athenian Mercury, focused on literary matters, in particular what was “new.” In addition to publishing a wide range of contemporary poets, the Gentleman’s Journal is unique in including not only the lyrics to new songs, but also the scores. During its two-year run, the Journal printed twenty songs by the celebrated musician Henry Purcell.Footnote 86 It also included a notable amount of short fiction, some thirty-six narratives that appeared under various titles ranging from “adventure,” “story,” “True History,” “fable,” and “novel.” Critics from the beginning of their commentary on this periodical have observed that the fictions are about contemporary people, places, and events, with Dorothy Foster arguing in 1917 that they “portray contemporary types, contemporary manners,” and Coperías-Aguilar in 2022 pointing to the degree to which the plots and character types have been drawn from contemporary social comedies that stressed realistic settings and characters.Footnote 87 As Coperías-Aguilar observes, the framing narrative that shapes the Journal and its contents, a fictive letter from a friend in London to a person in the city to keep them au currant with fashionable topics, music, and literature, “enhanced the fictionality of the ‘novels’ and also reinforced their condition of true stories.”Footnote 88

There is no evidence at present that the periodicals discussed in this section paid their contributors – as we have seen even warning them that they would not cover the cost of the Penny Post – although it would be reasonable to expect that other professional writers and musicians such as Wycherley and Handel might be. Instead, to generate content, they relied on creating a sense of community in their general reading audience, encouraging them to become content creators, and voluntarily to share their questions, literary works, and discoveries. It is clear, of course, that from the publishers’ and editors’ perspectives, the journals from their first conceptualization were intended to make a profit, and Dunton was particularly ingenious in devising ways in which his readers’ curiosity could be monetized. When the readers’ interest slacked and their contributions declined, the periodical ceased publication. As we shall explore in the next section, the periodicals that followed them preserved many of the features of this participatory, active audience which characterize the periodicals of the end of the seventeenth century, but as we shall see, with increasing commercial considerations for the writers.

3 Sociable Periodicals, 1700s–1720s, Continuity and Change: Aaron Hill’s the British Apollo, the Female Tatler, and Daniel Defoe’s the Review

… [news] media faces a scenario marked by global instability, economic crisis, misinformation, falling trust and renewed consumption habits with a specific challenge to reach young audiences. This scenario implies experimenting with channels, technologies and formats, to approach such an audience in an innovative, attractive, friendly, simple and fun way.

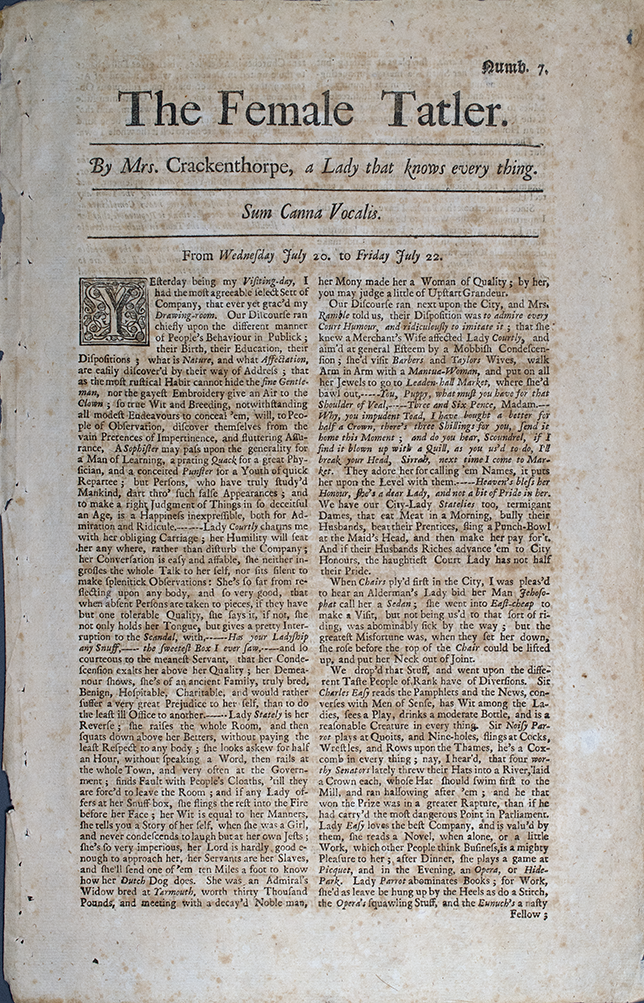

Two periodicals and a challenger to one highlight strategies used by what I am calling sociable periodicals to cultivate and sustain a subscribing participating readership over a long period of time. They did so in part by combining attractive features of their predecessors the Athenian Mercury and the Gentleman’s Journal with new types of content presentation and new marketing strategies to encourage readers to become paying followers rather than merely enjoying the copies offered for entertainment at public houses and helping to create its content. The British Apollo, which appeared twice weekly on Wednesdays and Fridays 1708–1709, then additionally on Mondays until 1711, was overseen by the poet Aaron Hill. It engaged in a lively literary spat with the upstart Female Tatler (July 1709–1710) for several months, August 1709 through early October, over some of its tactics to lure paying subscribers, including the use of music, and the quarrel between the two offers some revealing glimpses of the competition for readers as well as how the readers of this early form social media were viewed by the public at large.

Daniel Defoe’s periodical, the Review, originally titled A Review of the Affairs of FRANCE (October 1704–February 1705), was also initially published twice weekly, increasing to three times per week 1704–1713. Significantly, Defoe made use of the new, expanding postal system, and his paper appeared on Tuesdays, Thursday, and Saturdays, the same days that the Post Office in Lombard Street in London sent the post to all the English counties. As J. A. Downie points out, this means Defoe from the beginning was envisioning a national audience rather than a London one, that the periodical “appears to have been designed for distribution throughout England from the outset.”Footnote 90 As we shall see, while Defoe initially made use of several of the expected conventions of the sociable journal at the beginning of his periodical which was devoted to news of international affairs and domestic politics, over time the content as well as the relationship between the author and his readers would change.

3.1 Aaron Hill and the British Apollo, Mrs. Crackenthorpe and the Female Tatler, and the Battle over Readers

A decade after Dunton’s question and answer periodical stopped publishing, there was apparently sufficient demand again that another aspiring literary man, Aaron Hill, offered the public The British Apollo, which ran from February 1709 to 1711 [Figure 5]. This placed the British Apollo in direct competition with Steele’s the Tatler, which used a much different format and rapport with its target audience, which will be discussed in the next section. In its first issue, the British Apollo. Or, Curious Amusements for the Ingenious. To which are added the most Material Occurrences Foreign and Domestick. Perform’d by a Society of Gentlemen announced confidently to its potential subscribers that it would appear on Wednesday and Fridays, and that the Society of Gentlemen would