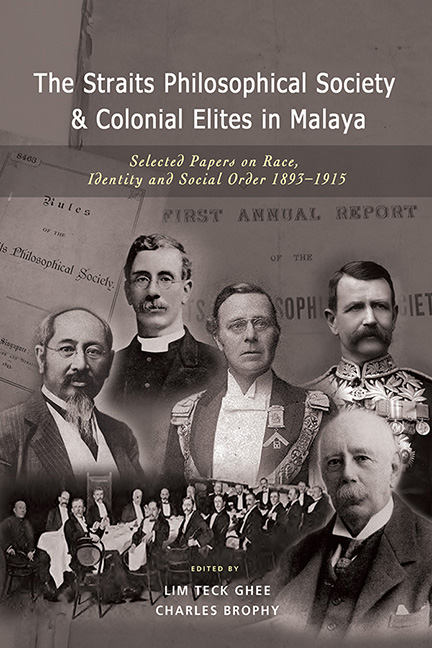

The Straits Philosophical Society and Colonial Elites in Malaya

The Straits Philosophical Society and Colonial Elites in Malaya Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 January 2024

Editors’ Note

Debates over the application of English law which took place throughout the British Empire often centred on the relationship between English law and existing customary practices. As Napier’s piece highlights British practice was to apply English law, except in cases of personal law where they regularly deferred to Hindu and Islamic legal practices. Yet in spaces like the Straits Settlements which were declared to be unoccupied land, no such recognition of customary law was afforded. The history of this problem was addressed by W.J. Napier in his Introduction to the Study of the Law Administered in the Colony of the Straits Settlements. In his 1899 paper to the Society he addressed this problem in reference to the Chinese population. This population, which had grown significantly from the 1870s, brought issues of marriage and inheritance amongst the Chinese in front of English-law courts. Yet the colonial administrators, many of whom had arrived in the Straits via India, had little or no familiarity with Chinese law, language and customs. This was the source of constant dissatisfaction amongst the Chinese community when they turned to British courts for justice. Whilst the British sought to better communicate English legal decisions in Chinese, a figure such as Governor Blundell feared that any attempt to translate English law into Chinese was “utterly hopeless” on account of the nature of the language.

The colony’s Arab community, on behalf of the Muslim community, had been able to lobby for the introduction of the Mohammedan Marriage Ordinance in 1880. But it was only until the 1890s in the Malay States that Chinese law began to attain greater recognition and a draft code on Chinese customary law was developed. This legacy of the division between the colonial administration and the Chinese population was one of the factors that laid the groundwork for the Chinese to adopt a system of self-government for the resolution of disputes and the regulation of social life through their clan networks.

This being a legal subject, it is impossible to divest it of its legal aspect, but I shall attempt to deal with it in as general a manner as I can.

To save this book to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle.

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox.

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive.