Published online by Cambridge University Press: 17 October 2019

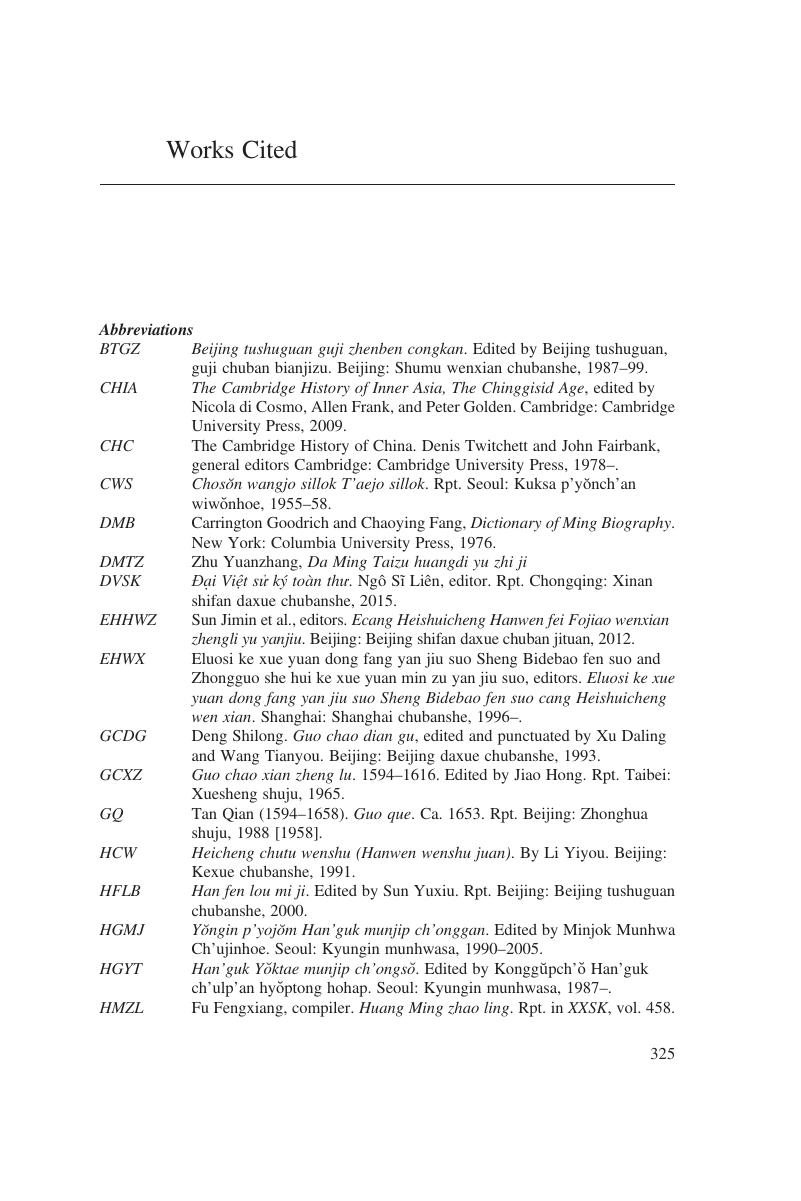

Beijing tushuguan guji zhenben congkan. Edited by Beijing tushuguan, guji chuban bianjizu. Beijing: Shumu wenxian chubanshe, 1987–99.

The Cambridge History of Inner Asia, The Chinggisid Age, edited by Nicola di Cosmo, Allen Frank, and Peter Golden. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

The Cambridge History of China. Denis Twitchett and John Fairbank, general editors Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978–.

Chosŏn wangjo sillok T’aejo sillok. Rpt. Seoul: Kuksa p’yŏnch’an wiwŏnhoe, 1955–58.

Carrington Goodrich and Chaoying Fang, Dictionary of Ming Biography. New York: Columbia University Press, 1976.

Zhu Yuanzhang, Da Ming Taizu huangdi yu zhi ji

Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư. Ngô Sĩ Liên, editor. Rpt. Chongqing: Xinan shifan daxue chubanshe, 2015.

Sun Jimin et al., editors. Ecang Heishuicheng Hanwen fei Fojiao wenxian zhengli yu yanjiu. Beijing: Beijing shifan daxue chuban jituan, 2012.

Eluosi ke xue yuan dong fang yan jiu suo Sheng Bidebao fen suo and Zhongguo she hui ke xue yuan min zu yan jiu suo, editors. Eluosi ke xue yuan dong fang yan jiu suo Sheng Bidebao fen suo cang Heishuicheng wen xian. Shanghai: Shanghai chubanshe, 1996–.

Deng Shilong. Guo chao dian gu, edited and punctuated by Xu Daling and Wang Tianyou. Beijing: Beijing daxue chubanshe, 1993.

Guo chao xian zheng lu. 1594–1616. Edited by Jiao Hong. Rpt. Taibei: Xuesheng shuju, 1965.

Tan Qian (1594–1658). Guo que. Ca. 1653. Rpt. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1988 [1958].

Heicheng chutu wenshu (Hanwen wenshu juan). By Li Yiyou. Beijing: Kexue chubanshe, 1991.

Han fen lou mi ji. Edited by Sun Yuxiu. Rpt. Beijing: Beijing tushuguan chubanshe, 2000.

Yŏngin p’yojŏm Han’guk munjip ch’onggan. Edited by Minjok Munhwa Ch’ujinhoe. Seoul: Kyungin munhwasa, 1990–2005.

Han’guk Yŏktae munjip ch’ongsŏ. Edited by Konggŭpch’ŏ Han’guk ch’ulp’an hyŏptong hohap. Seoul: Kyungin munhwasa, 1987–.

Fu Fengxiang, compiler. Huang Ming zhao ling. Rpt. in XXSK, vol. 458.

Kong Zhenyun. Huang Ming zhao zhi. Rpt. in XXSK, vol. 457.

Eluosi guoli Aiermitashi bowuguan cang Heishuicheng yishupin. Edited by Gosudarstvennyĭ Ėrmitazh, Xibei minzu daxue, and Shanghai guji chubanshe. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 2008–.

Hua yi yi yu. Edited by Qoninchi (Huo Yuanjie). Rpt. in HFLB, vol. 4.

Jishilu jianzheng. Yu Ben. Edited by Li Xinfeng. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 2015.

Koryŏsa. Compiled by Chŏng Inji et al. Rpt. Chongqing: Xishu shifan daxue chubanshe and Beijing, Remin daxue chubanshe, 2014.

Koryŏsa choryŏ. Compiled by Nam Sumun. 1452. Rpt. Seoul: Asea munhwasa, 1974.

Mingchao kaiguo wenxian. Rpt. Taibei: Xuesheng shuju, 1966.

Ming Hongwu yubi. By Zhu Yuanzhang. Original held at Palace Museum Library, Taibei. Rpt. as serial in Gugong zhoukan 1931–32.

Ming shi. Edited by Zhang Tingyu et al. 1736. Rpt. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1974.

Ming shi shi lu. By Yang Xueke. Annotated by Xu Song. Rpt. XXSK, shi 350.

Zhu Yuanzhang, Ming Taizu huangdi qinlu. Rpt. in Gugong tushu jikan 1, no. 4. Also rpt. as appendix to Zhang Dexin, “Taizu huangdi qinlu jiqi faxian yu yanjiu jilu.” Ming Qing luncong 6 (2005): 83–110.

Ming Taizu shilu. In Ming shilu. Compiled by Taibei: Zhongyang yanjiuyuan lishi yuyan yanjiusuo, 1962.

Ming Yingzong shilu. In Ming shilu. Compiled by Taibei: Zhongyang yanjiuyuan lishi yuyan yanjiusuo, 1962.

Mingdai zhuanji ziliao congkan. Beijing: Beijing tushuguan chubanshe, 2008.

Ni chen lu. Annotated by Wang Tianyou and Zhang Heqing. Beijing: Beijing daxue chubanshe, 1991.

Siku quanshu cunmu congshu. Edited by Siku quanshu cunmu congshu bianzuan weiyuanhui. Jinan: Qi Lu shushe, 1995–97.

Siku quanshu jinhuishu congkan. Edited by Siku quanshu jinhuishu congkan bianzuan weiyuanhui. Beijing: Beijing chubanshe, 1998.

Song Lian (1310–81). Song Lian quan ji. Hangzhou: Zhejiang guji chubanshe, 1999.

Xiaoling zhao chi. By Zhu Yuanzhang. Rpt. in Mingchao kaiguo wenxian. Taibei: Xuesheng shuju, 1966, vol. 4. Rpt. in Guojia tushuguan cang Xijian Mingshi shiji jicun, compiled by Guojia tushuguan fenguan. Beijing: Xianzhuang shuju, 2003, vol. 8.

Xuxiu Siku quanshu. Edited by Xuxiu Siku quanshu bianzuan weiyuanhui. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1995–2002.

Shen Defu. Wanli yehuo bian. 1619. Rpt. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1997.

Zhang Dan. Yunnan ji wu chao huang. Rpt. in SKCM, shi 45; YSC, vol. 4.

Yuan shi. 1360–70. Edited by Song Lian et al. Rpt. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1976.

Yunnan shiliao congkan. Edited by Fang Guoyu, et al. Kunming: Yunnan daxue chubanshe, 1998–2001.

Wang Shizhen. Yanshan tang bie ji. 1590. Rpt. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1985.

Yuwai Hanji zhenben wenku. Edited by Yuwai Hanji zhenben wenku bianzuan chuban weiyuanhui. Chongqing: Xinan shifan daxue chubanshe, 2008–2012.

Yuanshi yanjiu ziliao huibian. Edited by Yang Ne. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 2014.

Tala, Du Jianlu, and Gao Guoxiang, editors. Zhongguo cang Heishuicheng Hanwen wenxian. Beijing: Guojia tushuguan chubanshe, 2008.

To save this book to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle.

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox.

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive.