The 1968 Tet Offensive proved to be the turning point of the Vietnam War and its effects were far-reaching. Despite the fact that the communists were soundly defeated at the tactical level, the Tet Offensive resulted in a great psychological victory at the strategic level for them that set into motion the events that would lead to the election of Richard Nixon, the long and bloody US withdrawal from Southeast Asia, and ultimately the fall of South Vietnam.

The United States first committed ground combat troops in Vietnam in March 1965, when the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade came ashore on Red Beach near Đà Nẵng. A month later, President Lyndon Johnson authorized the use of US troops in offensive combat operations in Vietnam. This marked a major change in US involvement in the ongoing war between the South Vietnamese government in Saigon and the National Liberation Front (NLF). The American goal in Southeast Asia was to ensure a free, independent, noncommunist South Vietnam that would serve as a bulwark against the spread of communist influence and control in the Vietnamese countryside. However, the Saigon government and its armed forces were losing the battle against the NLF and things only worsened when Hanoi began to send North Vietnamese regulars down the Hồ Chí Minh Trail to join the fight in South Vietnam. Heretofore, US forces had been supporting the Saigon government with advisors and air support, but that approach proved inadequate. With the arrival of the marines, a massive US buildup ensued that resulted in more than 184,000 American troops in Vietnam by the end of 1965.

With the arrival of large numbers of American combat troops in South Vietnam, the US effort shifted to the conduct of military operations to destroy the People’s Liberation Armed Forces (PLAF, called the Viet Cong, or VC, by the allies) and their North Vietnamese counterparts, the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN). One of the first major battles between US forces and North Vietnamese troops occurred in November 1965 in the Ia Đrӑng Valley in the Central Highlands. Over the next two years, US forces under General William C. Westmoreland, commander of US Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), conducted many large-scale operations to find and destroy PLAF and PAVN forces in a war of attrition meant to wear down the enemy by killing or disabling so many of its soldiers that Hanoi’s will to prosecute the war would be broken.

As Westmoreland pursued his war of attrition, Hanoi ordered more PAVN troops down the Hồ Chí Minh Trail to join forces with the PLAF in their fight against the South Vietnamese troops and their American allies. By the middle of 1967, the war in Vietnam had degenerated into a bloody stalemate. US and South Vietnamese operations had inflicted heavy casualties on the PLAF and PAVN, but Hanoi continued to infiltrate troops into South Vietnam, and the NLF and PLAF still controlled the countryside in many areas in the south. Both the United States and North Vietnam had greatly increased their commitments to the battlefield, but neither side was able to defeat the other.

Antiwar Sentiment in the United States

In the United States, the lack of any meaningful progress on the battlefield began to erode public support for the Johnson administration’s handling of the war. As newspapers, magazines, and the nightly television news brought the war home to the United States, the antiwar movement grew. The toll of the fighting was mounting rapidly; the total number of US troops killed in action had grown from more than 2,300 in 1965 to more than 17,000 by the end of 1967. Scenes of the bloodshed and devastation resulting from the bitter fighting across South Vietnam led many Americans to the conclusion that the price of US involvement in the war was too high. The war was also aggravating social discontent on the homefront. Polls that initially reflected support for the president and his handling of the war began to turn against him. By June 1967, fully two-thirds of Americans polled said they had lost faith in Johnson’s ability to lead the country. A public opinion poll in September 1967 showed that for the first time more Americans opposed the war than supported it.Footnote 1 By this point, Johnson’s popularity had dropped to below 40 percent, a new low since he had first entered office. Meanwhile, antiwar protests continued to grow in size, and it was clear that the American public was becoming increasingly polarized over the war. Even many of those who supported the war effort were dissatisfied with Johnson’s inability to craft a winning strategy in Southeast Asia.

While many Americans believed that the war had degenerated into a bloody stalemate, General Westmoreland did not see it that way, and by his primary metric – the body count – the US and allied forces were making significant headway against the enemy on the battlefield. His headquarters continued to send reports to Washington touting the progress being made against the enemy, citing ever increasing enemy body counts.

Based on Westmoreland’s optimistic assessments and concerned about the downward trend in public opinion, President Johnson ordered a media blitz to convince the American people that the war was being won and that administration policies were succeeding. In what became known as the “Success Campaign,” administration officials took every opportunity to counter the perception that there was a stalemate on the battlefield in Vietnam and repeatedly stressed that progress was being made against the enemy.

As part of this effort, Johnson brought Westmoreland home in mid-November 1967 to make the administration’s case to the American public. In a number of venues, the general did just that. Upon his arrival at Andrews Air Force Base, Westmoreland told waiting reporters: “I have never been more encouraged in the four years that I have been in Vietnam. We are making real progress.”Footnote 2 The next day, at a press conference, he told reporters that the South Vietnamese army would be able to assume increasing responsibility for the fighting, permitting a “phase-out” of US troops “within two years or less.”Footnote 3 On November 21, in an address at the National Press Club, Westmoreland proclaimed, “We have reached an important point where the end becomes to come into view. I am absolutely certain that, whereas in 1965 the enemy was winning, today he is certainly losing. The enemy’s hopes are bankrupt.” He assured the assembled reporters and the American people that victory “lies within our grasp.”Footnote 4 Westmoreland later said that he was concerned at the time about fulfilling the public relations task, but he nevertheless gave a positive, upbeat account of how things were going in the war, clearly believing that a corner had been turned. For the time being, Westmoreland’s pronouncements helped calm a restive American public. However, his optimistic, upbeat reports would come back to haunt him very soon.

Planning for the New Offensive

Meanwhile, in Vietnam, even as Westmoreland spoke, the communists were finalizing preparations for a countrywide offensive designed to break the stalemate and “liberate” South Vietnam. According to William J. Duiker, the communists had earlier decided on a “decisive victory in a relatively short period of time,” which was confirmed by the 13th Plenum in late 1966.Footnote 5 This led to an aggressive battlefield strategy that achieved only limited results. By mid-1967, the party leaders in Hanoi decided that something had to be done to break the stalemate in the South. However, there followed a contentious debate in the Politburo about how best to do this. By this time, Lê Duẩn, a one-time organizer of the resistance in the south and by 1967 general secretary of the Lao Động Party (Vietnam Workers’ Party), had become critical of the protracted war strategy. The war was not going as well as the communists had hoped, chiefly because the commitment of American troops had blunted PAVN infiltration and imposed heavy casualties. To Lê Duẩn, the aggressive American tactics during the early part of 1967 did not bode well for the successful continuation of a protracted approach to prosecuting the war. However, two areas of potential allied weakness had emerged. The ARVN still had significant problems and it was clear that US public opinion had begun to waver in its support of the American war effort. For these reasons, Lê Duẩn advocated a more aggressive strategy to bring the war to an earlier conclusion by destroying US confidence and spreading communist control and influence in the countryside.

Lê Duẩn was not alone. Chief among those who agreed with him was General Nguyễn Chí Thanh, head of the Central Office for South Vietnam (COSVN), which was initially established in 1951 as the communist military headquarters in South Vietnam. Thanh also wanted to pursue a more aggressive strategy. He called for a massive attack against the cities of South Vietnam using local guerrillas, main-force PLAF, and PAVN regulars. This would mark the advent of the third, and final, stage of the revolutionary struggle – the general offensive, general uprising (Tổng công kích – Tổng khởi nghĩa or TCK–TKN).

Lê Duẩn and Thanh found other supporters in the Politburo, who were also unhappy with the stalemate in the South. One communist general later described the situation, saying, “In the spring of 1967 Westmoreland began his second campaign. It was very fierce. Certain of our people were very discouraged. There was much discussion of the war – should we continue main-force efforts, or should we pull back into a more local strategy. But by the middle of 1967 we concluded that you had not reversed the balance of forces on the battlefield. So we decided to carry out one decisive battle to force LBJ to de-escalate the war.”Footnote 6

Not everyone in the Politburo in Hanoi agreed with Lê Duẩn and Nguyễn Chí Thanh. Some historians, one of whom described the Tet Offensive as “Giáp’s Dream,” ascribe the genesis of the plan to Hanoi’s defense minister, Võ Nguyên Giáp.Footnote 7 However, Giáp actually opposed the proposed escalation because he thought that a major offensive in 1968 would be premature and was likely to fail against an enemy with vastly superior mobility and firepower.Footnote 8 Long the chief proponent of protracted guerrilla operations against allied communication and supply lines in the south, Giáp was afraid that, if the offensive failed, the revolution would be set back years. Giáp and Thanh had been long-time rivals for control of the communists’ military strategy in the South. Thanh charged Giáp with being “old fashioned.” He criticized Giáp for his “method of viewing things that is detached from reality,” insisting that Giáp and his followers looked for answers “in books, and [by] mechanically copying one’s past experiences or the experiences of foreign countries … in accordance with a dogmatic tendency.”Footnote 9

In the end, Lê Duẩn and Nguyễn Chí Thanh won the argument. After lengthy deliberation, the 13th Plenum in April 1967 passed Resolution 13 which called for a “spontaneous uprising in order to win a decisive victory in the shortest possible time.”Footnote 10 This was a blow for Giáp and his theory of protracted war. However, on July 6, 1967, Thanh suddenly died after suffering an apparent heart attack.Footnote 11 Despite Thanh’s death, Lê Duẩn directed that planning for the general offensive continue, and the responsibility for crafting the campaign fell to Giáp’s deputy, General Vӑn Tiến Dũng.Footnote 12

It was decided that the offensive would be launched in early 1968 during Vietnam’s Tết holiday, which traditionally marks the start of the lunar New Year. It is not only a time of revelry celebrated with feasts and fireworks, but also one of worship at the family altar for revered ancestors. For several days the entire countryside was on the move as people returned to their ancestral homes, and all business, even the business of war, came to a halt. Prior to 1968, both sides in the war had observed Tết ceasefires during the annual holiday. Therefore, the North Vietnamese reasoned that a large part of both the South Vietnamese army and the National Police would be on leave when Tết began, and that Saigon would be unprepared for a countrywide attack.

The plan for Tết Mậu Thân 1968 (Tet Spring Offensive of 1968) was finalized in late summer of 1967. North Vietnamese diplomats from around the world were called to Hanoi for consultation in July to discuss the upcoming offensive. This gathering should have been the first indication to allied intelligence that something significant was in the offing, but most allied analysts believed the meeting’s purpose was to consider a peace bid.

According to General Trần Vӑn Trà, commander of communist forces in the South from 1963 to 1975, the objectives of Tết Mậu Thân were “to break down and destroy the bulk of the puppet [South Vietnamese] troops, topple the puppet administration at all levels, and take power into the hands of the people; to destroy the major part of the US forces and their war materiel, and render them unable to fulfill their political and military duties in Vietnam; and to break the US will of aggression, force it to accept defeat in the South and put an end to all acts of war against the North.”Footnote 13 As part of the desire to break the American will, the communists hoped to convince the United States to end the bombing of the North and begin negotiations.Footnote 14 According to William J. Duiker, “Hanoi was counting on the combined offensive and uprising to weaken the political and military foundations of the Saigon regime and to trigger a shift in policy in the United States.”Footnote 15 To accomplish this, the offensive would target South Vietnamese urban centers.

The plan for the offensive called for a series of simultaneous surprise attacks against American bases and South Vietnamese cities.Footnote 16 Dũng specifically targeted previously untouched urban centers such as Saigon in the south, Nha Trang and Quy Nhơn in central South Vietnam, and Quảng Ngãi and Huế in the northern part of the country.

Ultimately, Dũng’s plan was predicated on three assumptions. First, he assumed that the ARVN would not fight when struck a hard blow. Second, he believed that the Saigon government had no support among the South Vietnamese people, who would rise up against President Nguyễn Vӑn Thiệu if given the opportunity. Third, he assumed that both the people and the armed forces of South Vietnam despised the Americans and would turn on them if given the chance.

Preparations for the Offensive

Dũng’s plan called for a preparatory phase that would be conducted from September to December 1967. During this period, PAVN forces would launch attacks in the remote outlying regions along South Vietnam’s borders with Cambodia and Laos. The purpose of these operations, which were essentially a grand feint, would be to draw US forces away from the populated areas.Footnote 17 This would leave the cities and towns uncovered. This phase would have two other objectives. The first was to provide opportunities for Dũng’s troops to hone their fighting skills, and the other was to increase American casualties. As part of this preparatory phase, main-force divisions would begin to move into position around Khe Sanh, an outpost along the Laotian border manned by only a single US marine regiment. Additionally, the battles along South Vietnam’s borders served to screen the infiltration of troops and equipment into South Vietnam from Laos and Cambodia prior to Tết.

General Trần Vӑn Trà asserted some years after the war that the plan for the offensive called for three distinct phases.Footnote 18 Phase I, which was scheduled to begin on January 31, 1968, was a countrywide assault on South Vietnamese cities, ARVN units, American headquarters, communication centers, and air bases to be carried out primarily by Viet Cong main-force units. It was hoped that the Southern insurgents would be able to infiltrate their forces into the attack positions and target areas before the offensive started.

Concurrent with this phase would be a massive propaganda campaign aimed at coaxing the Southern troops to rally to the communist side. The objective of this campaign was to achieve wholesale defections from ARVN ranks. At the same time, the North Vietnamese would launch their political offensive aimed at causing the South Vietnamese people to revolt against the Saigon government. Successful accomplishment of this objective would leave “the American forces and bases isolated islands in a sea of hostile South Vietnamese people.”Footnote 19

If the general uprising did not occur or failed to achieve the overthrow of the Saigon government, follow-on operations would be launched in succeeding months to wear down the enemy and lead either to victory or to a negotiated settlement.Footnote 20 According to Trà, Phase II of the offensive began on May 5, and Phase III began on August 17 and ended on September 23, 1968.Footnote 21 It is clear that, to Hanoi and the NLF, the Tet Offensive, which is usually seen by many American historians to cover a much shorter time period, was a more prolonged offensive that lasted beyond the action immediately following the Tết holiday.

Interpreting the enemy’s moves in the latter months of 1967 as an effort to gain control of the northern provinces, General Westmoreland retaliated with massive bombing raids targeted against suspected PAVN troop concentrations. He also sent reinforcements to the northern and border areas to help drive back PAVN attacks in the region. The attack on Dak To in II Corps in November 1967 was the last of a series of “border battles” that began two months earlier with the siege of Cồn Thiện in I Corps and continued in October with attacks on Sông Bé and Lộc Ninh in III Corps.Footnote 22

In purely tactical terms, these operations were costly failures and, although exact numbers are not known, the communists no doubt lost some of their best troops. Not only did the allied forces exact a high toll in enemy casualties, the attacks failed to cause a permanent relocation of allied forces to the border areas. The strategic mobility of the American forces permitted them to move to the borders, turn back the communist attacks, and redeploy back to the interior in a mobile reserve posture. North Vietnamese colonel Tran Van Doc later described these border battles as “useless and bloody.”Footnote 23 Nevertheless, at the operational level, the attacks achieved the intent of Hanoi’s plan by diverting Westmoreland’s attention to the outlying areas away from the buildup around the urban areas that would be targeted in the coming offensive. Additionally, they gave the North Vietnamese an opportunity to perfect the tactics that they would use in the Tết attacks.Footnote 24

While these battles raged, General Dũng masterfully directed an intensive logistical effort focused on a massive buildup of troops and equipment in the South. Men and arms began pouring into South Vietnam from staging areas in Laos and Cambodia. New Russian-made AK-47 assault rifles, B-40 and 122mm rockets, and large amounts of other war materiel were moved south along the Hồ Chí Minh Trail by bicycle, ox cart, and trucks.

As the PAVN troops infiltrated into the South, PLAF units began making preparations for the coming offensive. Guerrilla forces were reorganized into the configuration that would later be employed in attacking the cities and towns. Replacements arrived to round out understrength units. The new weapons and equipment that had just arrived were issued to the troops. Food, medicine, ammunition, and other critical supplies were stockpiled. In areas close enough to the cities to permit rapid deployment but far enough away to preclude detection, PLAF units conducted intense training for the upcoming combat operations. Some training in street fighting was conducted for special sapper units, but this was limited in order to maintain secrecy. Reconnaissance was conducted of routes to objective areas and targets. Meanwhile, political officers conducted sessions in which they indoctrinated the troops by proclaiming that the final goal was within their grasp and exhorting them to prepare themselves for the decisive battle to achieve total victory against Saigon and its American allies.

To achieve tactical surprise, the North Vietnamese relied on secrecy to conceal preparations for the offensive. Specific operational plans for the offensive were kept strictly confidential and disseminated to each subordinate level only as requirements dictated. Although the executive members of COSVN knew of the plan sometime in mid-1967, it was not until the fall that the complete plan was disseminated to high-ranking enemy officials of the Saigon–Chợ Lớn–Gia Định Special Zone.Footnote 25 Although this secrecy was necessary for operational security, it would add to the customary fog and friction of war once the offensive was launched and have a significant impact on the outcome of the fighting at the tactical level.

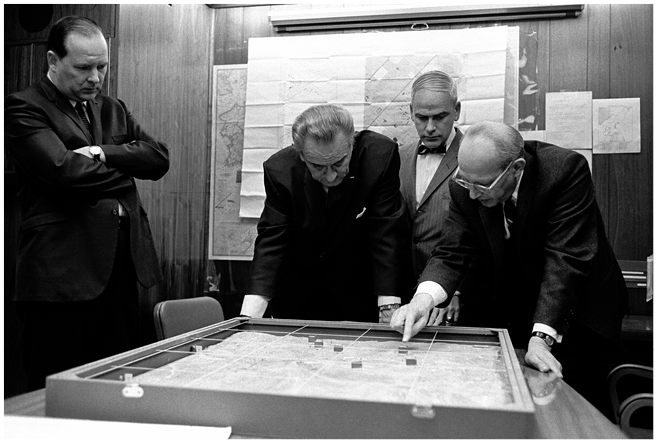

Figure 13.1 Walt Whitman Rostow (right) shows White House press secretary George Christian (left), President Lyndon B. Johnson (second left), and General Robert Ginsburgh (second right) a model of the Khe Sanh area (February 1968).

US Intelligence and the Fight for Khe Sanh

US military intelligence analysts knew that the communists were planning some kind of large-scale attack, but did not believe it would come during Tết or that it would be nationwide. Still, there were many indicators that the enemy was planning to make a major shift in its strategy to win the war. In late November, the CIA station in Saigon compiled all the various intelligence indicators and published a report called “The Big Gamble.”Footnote 26 This was not really a formal intelligence estimate or even a prediction, but rather “a collection of scraps” that concluded that the communists were preparing to escalate the fighting.Footnote 27 This report also put enemy strength at a much higher level than previously supposed. Military intelligence analysts at MACV strongly disagreed with the CIA’s estimate, because at the time the command was changing the way it was accounting for the enemy and was reducing its estimate of enemy capabilities. Nevertheless, as more intelligence poured in, Westmoreland and his staff came to the conclusion that a major enemy effort was probable. All the signs pointed to a new offensive. Still, most of the increased enemy activity had been along the DMZ and in the remote border areas. In late December 1967, additional signals intelligence revealed that there was a significant enemy buildup around Khe Sanh.

Surrounded by a series of mist-enshrouded, jungle-covered hills, Khe Sanh Combat Base (KSCB) was one of a series of outposts established near the demilitarized zone (DMZ) separating North and South Vietnam. Located just north of Khe Sanh village some 7 miles (11 km) from the border with Laos and about 14 miles (22.5 km) south of the DMZ, the marine base was a key element in the defense of I Corps in South Vietnam. It effectively controlled a valley which was the crossroads of enemy infiltration routes from North Vietnam and lower Laos that provided natural invasion avenues of approach into South Vietnam’s two northernmost provinces. To Westmoreland, Khe Sanh was the natural blocking position to impede enemy infiltration into South Vietnam in order to protect Quảng Trị and Thừa Thiên provinces.

The marines at Khe Sanh had been involved in a protracted struggle with North Vietnamese forces since mid-1967 for control of the high ground that surrounded the base. In late November of that year, US intelligence began to receive reports that several PAVN divisions in North Vietnam were beginning to move south. By late December it was apparent to US intelligence agencies that two of these divisions were headed for the Khe Sanh area.

Concerned with a new round of intelligence indicators and the situation developing at Khe Sanh, Westmoreland requested that the South Vietnamese cancel the coming countrywide Tết ceasefire. On January 8, 1968, the chief of the South Vietnamese Joint General Staff (JGS), General Cao Vӑn Viên, told Westmoreland that he would try to limit the truce to twenty-four hours. However, South Vietnamese president Thiệu argued that to cancel the 48-hour truce would adversely affect the morale of his troops and the South Vietnamese people. Nevertheless, he agreed to limit the ceasefire to thirty-six hours, beginning on the evening of January 29. Traditionally, as previously stated, South Vietnamese soldiers returned to their homes for the Tết holiday, and this fact would play a major role in the desperate fighting to come.

On January 21, the North Vietnamese began the first large-scale shelling of the marines at Khe Sanh, which was followed by renewed sharp fights between the enemy troops and the marines in the hills surrounding the base. Westmoreland was sure that this was the opening of the long-anticipated enemy general offensive. The fact that the Khe Sanh situation looked similar to that which the French had faced when they were decisively defeated at Điện Biên Phủ in 1954 only added urgency to the unfolding events there. With the increase in enemy activity around Khe Sanh, Westmoreland ordered the commencement of Operation Niagara II, a massive bombing campaign focused on suspected enemy positions around the marine base. He also ordered the 1st Cavalry Division from the Central Highlands to Phú Bài, just south of Huế. Additionally, he sent one brigade of the 101st Airborne Division to I Corps to strengthen the defenses of the two northernmost provinces. By the end of January, more than half of all US combat maneuver battalions were located in the I Corps area, ready to meet any new threat.

Essentially, US and ARVN forces were preparing for the wrong battle. The Tet Offensive represented, in the words of National Security Council staff member William Jorden, writing in a February 1968 cable to presidential advisor Walt Rostow, “the worst intelligence failure of the war.”Footnote 28 Many historians and other observers have endeavored to understand how the communists were able to achieve such a stunning level of surprise. There are a number of possible explanations. First, allied estimates of enemy strengths and intentions were flawed. Part of the problem was that MACV had changed the way that it computed enemy order of battle and had downgraded the intelligence estimates about total PLAF and PAVN strength, no longer counting the National Liberation Front local militias in the enemy order of battle. CIA analyst Sam Adams later charged that MACV actually falsified intelligence reports to show progress in the war.Footnote 29 Whether this accusation was true is subject to debate, but it is a fact that MACV revised enemy strength downward from almost 300,000 to 235,000 in December 1967. US military intelligence analysts apparently believed their own revised estimates and largely disregarded the mounting evidence that the communists not only retained a significant combat capability, but also planned to use that capability in a dramatic fashion.

Given these grossly flawed intelligence estimates, senior allied military leaders and most of their intelligence analysts greatly underestimated the capabilities of the enemy and dismissed new intelligence indicators because they too greatly contradicted prevailing assumptions about the enemy’s strength and capabilities. It was thought that enemy capabilities were insufficient to support a nationwide campaign. One analyst later admitted that he and his colleagues had become “mesmerized by statistics of known doubtful validity … choosing to place our faith in the ones that showed progress.”Footnote 30 These entrenched beliefs about the enemy served as blinders to the facts, coloring the perceptions of senior allied commanders and intelligence officers when they were presented with intelligence that differed so drastically from their preconceived notions.

Another problem that had an impact on the intelligence failures in the Tet Offensive deals with what is known today as “fusion.” Given the large number of indicators drawn from a number of sources operating around South Vietnam, the data collected was difficult to assemble into a complete and cohesive picture of what the communists were doing. The analysts often failed to integrate cumulative information, even though they were charged with the production of estimates that should have facilitated the combination of different indicators into an overall analysis. Part of this problem can be traced to the lack of coordination between allied intelligence agencies. Most of these organizations operated independently and rarely shared their information with each other. This lack of coordination and failure to share information impeded the synthesis of all the intelligence that was available and precluded the fusion necessary to predict enemy intentions and prevent the surprise of the enemy offensive when it came.

Even if the allied intelligence apparatus had been better at fusion, it would still have had to deal with widely conflicting reports that further clouded the issue. While the aforementioned intelligence indicated that a general offensive was in the offing, there were a number of other intelligence reports indicating that the enemy was facing extreme hardships in the field and that his morale had declined markedly. It was difficult to determine which reports to believe. Additionally, some indicators that should have caused alarm among intelligence analysts got lost in the noise of developments related to more obvious and more widely expected adversary threats. Faced with evidence of increasing enemy activity near urban areas and along the borders of the country, the allies were forced to decide where, when, and how the main blow would fall. They failed in this effort, choosing to focus on the increasing intensity of activity and engagements at Khe Sanh and in the other remote areas.

Westmoreland and his analysts failed to foresee a countrywide offensive, thinking that there would be perhaps a “show of force,” but otherwise the enemy’s main effort would be directed at the northern provinces. When indications that North Vietnamese army units were massing near Khe Sanh were confirmed by the attack on the marine base on January 21, this fit well with what Westmoreland and his analysts already expected. Thus, they evaluated the intelligence in light of what they already believed, focusing on Khe Sanh and discounting most of the rest of the indicators that did not fit with their preconceived notions about enemy capabilities and intentions.

Surprise Attack

For these reasons, the Tet Offensive achieved almost total surprise. This is true even though a number of attacks were launched prematurely against five provincial capitals in II Corps Tactical Zone and Đà Nẵng in I Corps Tactical Zone in the early morning hours of January 30.Footnote 31 These early attacks, now credited to enemy coordination problems, provided at least some warning, but many in Saigon continued to believe that these attacks were only meant to divert attention away from Khe Sanh, and no one anticipated the magnitude of the attacks to come.

The Tet Offensive began in full force shortly before 3 a.m. on January 31. A force of more than 84,000 communist troops – a mixture of PAVN regulars and PLAF main-force guerrillas – began a coordinated attack throughout South Vietnam.Footnote 32 The PAVN and PLAF targeted more than three-quarters of the provincial capitals and most of the major cities. In the north, communist forces struck Quảng Trị, Tam Kỳ, and Huế, as well as the US military bases at Phú Bài and Chu Lai. In the center of the country, they followed up the previous evening’s attacks and launched new ones at Tuy Hòa, Phan Thiết, and the American installations at Bong Song and An Khê. In III Corps Tactical Zone, the primary communist thrust was at Saigon itself, but there were other attacks against the ARVN corps headquarters at Biên Hòa and the US II Field Force headquarters at Long Bình. In the Mekong Delta, the VC struck Vĩnh Long, Mỹ Tho, Cần Thơ, Định Tường, Kiến Tường, Gò Công, and Bến Tre, as well as virtually every other provincial capital in the region. The communist forces mortared or rocketed every major allied airfield and attacked sixty-four district capitals and scores of lesser towns, villages, and hamlets.

Although the attacks varied in size and scope, they generally followed the same pattern. They began with a barrage of mortar and rocket fire, followed closely thereafter by a ground assault spearheaded by sappers, who penetrated the defensive perimeter. Once inside the cities, the commandos linked up with troops that had previously infiltrated and with local sympathizers, who often acted as guides. The commandos were followed by main-force units, who quickly seized predetermined targets. They were usually accompanied by propaganda teams who tried to convince the local populace to rise up against the Saigon government. The attackers were both skillful and determined and had rehearsed their attacks beforehand.

The surprise and scope of the Tet Offensive were stunning; everywhere there was confusion, shock, dismay, and disbelief on the part of the allies. The carefully coordinated attacks, as journalist Stanley Karnow writes, “exploded around the country like a string of firecrackers.”Footnote 33 As previously stated, US intelligence had gathered some information of infiltration into Southern population centers and captured documents that outlined the general plan. However, Westmoreland and his intelligence staff were so convinced that Khe Sanh was the real target and that the enemy was incapable of conducting an offensive on such a massive scale that they viewed the captured documents as a diversionary tactic. “Even had I known exactly what was to take place,” Westmoreland’s intelligence officer later conceded, “it was so preposterous that I probably would have been unable to sell it to anybody.”Footnote 34 Westmoreland himself later admitted that he had not anticipated the “true nature or the scope” of the attacks.Footnote 35 Consequently, the US high command had seriously underestimated the enemy’s potential for a major, nationwide offensive, and the allies were almost overwhelmed initially by the audacity, scale, and intensity of the attacks.

In Saigon, in one of the most spectacular attacks of the entire offensive, nineteen Viet Cong sappers conducted a daring raid on the new US Embassy, which had just been opened in September. Elsewhere in the capital city, the communists committed thirty-five battalions, attacking every major installation, including Tân Sơn Nhất Air Base, the presidential palace, and the headquarters of South Vietnam’s general staff. Additionally, they hit nearby installations at Long Bình and Biên Hòa. At his headquarters, the US commander responsible for the defense of the area surrounding Saigon said that the situation map showing the reported attacks reminded him of “a pinball machine, one light after another going on as it was hit.”Footnote 36

Far to the north, 7,500 NLF and North Vietnamese troops overran and occupied Huế, the ancient imperial capital that had been the home of the emperors of the Kingdom of Annam. The battle to recapture the city lasted more than three weeks and resulted in bitter house-to-house fighting that destroyed a large part of the city. The battle had also taken a tremendous toll on the population of Huế. Immediately following the battle and in the months afterward, more than 2,800 bodies of South Vietnamese men, women, and children were found in several mass graves around the city. Reportedly these were part of the group that had been identified as “reactionaries,” who had been rounded up by communist cadres when PAVN and PLAF forces initially took over the city and were executed during the course of the battle.

In addition to the bloody battle for Huế, fighting raged in Quảng Trị, Đà Lạt, Kontum, Pleiku, and Ban Mê Thuột in the Central Highlands, as well as in Cần Thơ, Mỹ Tho, Sóc Trӑng, and Bến Tre in the Mekong Delta, but, ultimately, allied troops, as in Huế eventually, prevailed in all of these battles.

Outcomes

In the United States, news of the widespread attacks and vivid images of the bitter fighting, unprecedented in its magnitude and ferocity, came as a great shock to the American people. The attacks sharply contradicted the optimistic reports that had come out of the Johnson administration in the closing months of 1967. Television news anchor Walter Cronkite perhaps said it best when he asked, no doubt voicing the sentiment of many Americans, “What the hell is going on? I thought we were winning the war.”Footnote 37

In truth, the Tet Offensive and subsequent fighting into the fall of 1968 turned out to be a disaster for the communists, at least at the tactical level. While the North Vietnamese and NLF achieved initial success with their surprise attacks, allied forces rapidly recovered their balance and responded quickly, containing and driving back the attackers in most areas. The stunning attack on the US Embassy was over in a matter of hours, with all the attackers either killed or captured.

The first surge of the offensive was over by the second week of February, and most of the battles were over in a few days, but heavy fighting continued in a number of places around the country. Marines were still under siege at Khe Sanh. Protracted battles also raged for several weeks in several areas of Saigon and in Huế, but in the end allied forces used superior mobility and firepower to rout the communists, who failed to hold any of their military objectives. The communists expected the South Vietnamese forces to collapse, but, for the most part, they acquitted themselves well in the heavy fighting. As for the much-anticipated general uprising of the South Vietnamese people, it never materialized. The communists had launched the offensive, counting on the general uprising to reinforce their attacks; when it did not happen, they lost the initiative and were forced to withdraw or die in the face of the allied response.

That did not mean that the fighting was over. In May, the PAVN and PLAF launched what became known as “mini-Tet,” focused on Saigon and the area just south of the DMZ. In this phase, as in the initial offensive, communist forces sustained a costly defeat. There was a third wave in the early fall, but these attacks were also turned away by the allied defenders.

During the bitter fighting, the communists sustained staggering casualties. Official MACV estimates put communist losses in the first months of 1968 at around 45,000 killed, with an additional 7,000 captured. The total estimate of enemy killed has been disputed, but it is clear that their losses were heavy, and the numbers continued to grow as subsequent fighting extended into the summer and autumn months. By the end of September, when the offensive had largely run its course, the NLF, which bore the brunt of much of the heaviest fighting in the cities, had been dealt a significant blow from which it never completely recovered.

The Tet Offensive resulted in an overwhelming defeat of the communist forces at the tactical level, but the fact that the enemy had pulled off such a widespread offensive and caught the allies by surprise ultimately contributed to victory for the communists at the strategic level. Although the US and allied casualties were lower than those of the enemy, they were still extremely high; US losses through the end of March were more than 3,600 killed in action, while the South Vietnamese during the same time period suffered 7,600 killed and many more wounded.Footnote 38 These casualty figures and those for the subsequent phases combined with the sheer scope and ferocity of the offensive and the vivid images of the savage fighting on the nightly television news stunned the American people, who were astonished that the enemy was capable of such an effort. They were unprepared for the intense and disturbing scenes they saw on television because Westmoreland and the administration had told them that the United States was winning and that the enemy was on its last legs.

Although there was a brief upturn in the support for the administration in the days immediately following the launching of the offensive, it was short-lived, and subsequently the president’s approval rating plummeted.Footnote 39 Having accepted the optimistic reports of military and government officials in late 1967, many Americans now believed that there was no end to the war in sight and, more importantly, many felt that they had been lied to about progress on the battlefield. The Tet Offensive severely strained the administration’s credibility with the American people and increased public discontent with the war.

The Tet Offensive also had a major impact on the White House. It profoundly shook the confidence of the president and his advisors. Despite Westmoreland’s claims that the Tet Offensive had been a great victory for the allied forces, Johnson, like the American people, was stunned by the ability of the communists to launch such widespread attacks. One advisor later commented that an “air of gloom” hung over the White House.Footnote 40 When Westmoreland, urged on by General Earle Wheeler, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, asked for an additional 206,000 troops to “take advantage of the situation,” the president balked and ordered a detailed review of US policy in Vietnam by Clark Clifford, who was to replace Robert McNamara as secretary of defense. According to The Pentagon Papers, “A fork in the road had been reached and the alternatives stood out in stark reality.”Footnote 41

The Tet Offensive fractured the administration’s already wavering consensus on the conduct of the war, and Clifford’s reassessment permitted the airing of these new alternatives. The civilians in the Pentagon recommended that allied efforts focus on population security and that the South Vietnamese be forced to assume more responsibility for the fighting while the United States pursued a negotiated settlement. The Joint Chiefs naturally took exception to this approach and recommended that Westmoreland be given the troop increase he had requested and be permitted to pursue enemy forces into Laos and Cambodia. Completing his study, Clifford recommended that Johnson reject the military’s request and shift efforts toward deescalation.Footnote 42 Although publicly optimistic, Johnson had concluded that the current course in Vietnam was not working. He was further convinced that a change in policy was needed after the “Wise Men,” a group of senior statesmen to whom he had earlier turned for counsel and who had previously been very supportive of the administration’s Vietnam policies, advised that deescalation should begin immediately.

With these debates ongoing in the White House, Congress got into the act on March 11 when the Senate Foreign Relations Committee began hearings on the war. The House of Representatives initiated its own review of Vietnam policy the following week. Meanwhile, public opinion polls revealed the continuing downward trend in the president’s approval rating. This situation manifested itself in the Democratic Party presidential primary in New Hampshire, where the president barely defeated challenger Senator Eugene McCarthy (D-Minnesota), a situation which convinced Senator Robert Kennedy (D-New York) to enter the presidential race as an antiwar candidate.

Beset politically by challengers from within his own party and seemingly still in shock from the spectacular Tết attacks, Johnson went on national television on the evening of March 31, 1968, announcing a partial suspension of the bombing campaign against North Vietnam and calling for negotiations. He then stunned the television audience by announcing that he would not run for reelection: the Tet Offensive had claimed its final victim.

In many ways, Johnson was the architect of his own demise. He and Westmoreland built a set of, as it turned out, false expectations about the situation in Vietnam in order to win support for the administration’s handling of the war and dampen the antiwar sentiment. These expectations, based on a severely flawed (or manipulated, if one believes Sam Adams) intelligence picture, played a major role in the stunning impact of the Tet Offensive. The images and news stories of the bitter fighting seemed to put the lie to the administration’s claims of progress in the war and stretched the credibility gap to the breaking point. The tactical victory achieved on the battlefield quickly became a strategic defeat for the United States and led to the virtual abdication of the president.

North Vietnamese general Trần Độ acknowledged that the offensive had failed to achieve its major tactical objectives, but added, “As for making an impact in the United States, it had not been our intention – but it turned out to be a fortunate result.”Footnote 43 That result occurred because Westmoreland and the Johnson administration let political considerations overwhelm an objective appraisal of the military situation. In doing so, they used flawed intelligence to portray an image of decreasing enemy capabilities in order to garner public support. When the fallacy of this approach was revealed by the vivid images of the Tết fighting, the resulting loss of credibility for the president and the military high command in Saigon was devastating to both the Johnson administration and the allied war effort.

The Tet Offensive and its aftermath significantly altered the nature of the war in Vietnam. The resounding tactical victory was seen as a defeat in the United States. It proved to many Americans that the war was unwinnable; ultimately, the Tet Offensive effectively toppled a president, convinced the new president to “Vietnamize” the war, and paved the way for the ultimate triumph of the communist forces in 1975. Perhaps journalist Don Oberdorfer said it best when he wrote, “The North Vietnamese and Viet Cong lost a battle. The United States Government lost something even more important – the confidence of its people at home.”Footnote 44