1. Introduction

Brueghel's painting, The Fight Between Carnival and Lent (1559), contrasts the vices and virtues of puritanical moral standards. On one side of the painting, “men and women dance, they crowd into a tavern, get drunk, play games, watch street theatre, ignore beggars, sneak inside for sex, play cruel tricks on others, gamble, eat, join masked processions, and make music; in short, they are unruly, profane, sexually promiscuous, spontaneous, and concerned with immediate gratification” (Martin, Reference Martin2009, p. 9). On the other side of the painting, other “men and women work, attend church, give alms to beggars and the poor; in short they are orderly, sober, devout, and disciplined” (Martin, Reference Martin2009, pp. 9–10). This side represents the values of “decency, diligence, gravity, modesty, orderliness, prudence, reason, self-control, sobriety, and thrift” (Burke, Reference Burke1978, p. 213).

In recent decades, moral psychologists have identified a related cluster of moral norms. They have noted that many human societies praise chastity, temperance, and piety; condemn the immoderate enjoyment of sensual pleasures; and disapprove of the lack of religious and ritual observance (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt, Koleva, Motyl, Iyer, Wojcik and Ditto2013; Haidt, Reference Haidt2007, Reference Haidt2012; Haidt & Joseph, Reference Haidt and Joseph2007; Shweder, Mahapatra, & Miller, Reference Shweder, Mahapatra, Miller, Kagan and Lamb1987, Reference Shweder, Much, Mahapatra and Park1997). This constellation of moral values gained popularity in psychological and evolutionary approaches to morality as part of the so-called “purity” moral concerns (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt, Koleva, Motyl, Iyer, Wojcik and Ditto2013; Haidt, Reference Haidt2007, Reference Haidt2012; Haidt & Joseph, Reference Haidt and Joseph2004, Reference Haidt and Joseph2007). The purity category, however, is a murky concept with no clear definition (Crone, Reference Crone2022; Gray, DiMaggio, Schein, & Kachanoff, Reference Gray, DiMaggio, Schein and Kachanoff2022; Kollareth, Brownell, Duran, & Russell, Reference Kollareth, Brownell, Duran and Russell2022). Reviewing 158 papers of the purity literature, Gray et al. (Reference Gray, DiMaggio, Schein and Kachanoff2022) show that moral psychologists understand purity in about nine different ways, often mixing distinct meanings in their definitions and operationalizations. To avoid confusions, we here use the term puritanical morality (or “puritanism”) to refer to the ascetic, austere moralization of apparently victimless pleasures that humans crave for, such as eating, drinking, feasting, dancing, gambling, taking drugs, dressing indecently, having sex, or masturbating.

Puritanical morality, more precisely, comprises the following constellation of moral norms:

(1) A moral condemnation of bodily pleasures. Christian morality, for example, condemns excessive indulgence in food and sex as the deadly sins of gluttony and lust (Adamson, Reference Adamson2004; Dabhoiwala, Reference Dabhoiwala2012; Hill, Reference Hill2011). Psychologists have observed that many participants moralize unrestrained or unhealthy eating (Fitouchi, André, Baumard, & Nettle, Reference Fitouchi, André, Baumard and Nettle2022; Mooijman et al., Reference Mooijman, Meindl, Oyserman, Monterosso, Dehghani, Doris and Graham2018; Ringel & Ditto, Reference Ringel and Ditto2019; Steim & Nemeroff, Reference Steim and Nemeroff1995), as well as sexual indulgences such as masturbation or oral sex (Fitouchi et al., Reference Fitouchi, André, Baumard and Nettle2022; Haidt & Hersh, Reference Haidt and Hersh2001; Haidt, Koller, & Dias, Reference Haidt, Koller and Dias1993; Schein, Ritter, & Gray, Reference Schein, Ritter and Gray2016).

(2) A strong valorization of temperance and self-discipline. In various countries, a substantial share of participants moralize lack of self-control (Mooijman et al., Reference Mooijman, Meindl, Oyserman, Monterosso, Dehghani, Doris and Graham2018), general hedonism (Saroglou & Craninx, Reference Saroglou and Craninx2021), and reluctance to needless effort (Celniker et al., Reference Celniker, Gregory, Koo, Piff, Ditto and Shariff2023; Tierney et al., Reference Tierney, Hardy, Ebersole, Viganola, Clemente, Gordon and Uhlmann2021), whereas similar values are preached across world religions (see sect. 1.1). In medieval and early modern Western societies, for instance,

self-discipline in all spheres of life was prized as the ultimate mark of civilization … Only beasts and savages gave “unrestrained liberty” to “the cravings of nature” – civilized Christians were rather “to bring under the flesh; bring nature under the government of reason, and, in short bring the body under the command of the soul.” The mental and physical government of fleshly appetites was the very foundation of the whole culture of discipline. (Dabhoiwala, Reference Dabhoiwala2012, pp. 26–27)

(3) Condemnations of entertainments such as alcohol, drug use, gambling, and certain forms of music and dances. These are widespread both in cross-national surveys (Lugo, Cooperman, Bell, O'Connell, & Stencel, Reference Lugo, Cooperman, Bell, O'Connell and Stencel2013; Poushter, Reference Poushter2014; Weeden & Kurzban, Reference Weeden and Kurzban2013), and in the explicit moral codes of various societies (e.g., Buddhism: Najjar, Young, Leasure, Henderson, & Neighbors, Reference Najjar, Young, Leasure, Henderson and Neighbors2016; Sterckx, Reference Sterckx2005, pp. 223–224; Hinduism: Doniger, Reference Doniger2014, pp. 263–270; traditional Europe: Burke, Reference Burke1978; Martin, Reference Martin2009; Partridge & Moberg, Reference Partridge and Moberg2017; Wagner, Reference Wagner1997; Arab-Muslim societies: Michalak & Trocki, Reference Michalak and Trocki2006; Otterbeck & Ackfeldt, Reference Otterbeck and Ackfeldt2012).

(4) Moral demands of modesty, which regulate decency in clothing, speech, and attitudes. In traditional Arab-Muslim societies, for example, when entering the public sphere, women must be veiled, lower their gaze, and avoid body ornaments (Antoun, Reference Antoun1968; Beckmann, Reference Beckmann2010; Mernissi, Reference Mernissi2011), whereas similar restrictions appear in other puritanical cultures (e.g., Puritans' austere clothing: Bremer, Reference Bremer2009; Hindu India: Stephens, Reference Stephens1972, p. 4; Jewish Tznihut dress: Andrews, Reference Andrews2010; ancient Christian veiling: Tariq, Reference Tariq2014).

(5) Moral prescriptions of a pious lifestyle, requiring the diligent observance of religious rituals, such as fasting, daily prayers, meditations, effortful pilgrimages, or dietary restrictions (see sect. 1.1).

This definition of puritanism comprises many core elements of purity, which is often defined by moral psychologists as including moralizations of lust, gluttony (Haidt & Graham, Reference Haidt and Graham2007; Mcadams et al., Reference Mcadams, Albaugh, Farber, Daniels, Logan and Olson2008), clothing, prayer, meditation, temperance, self-control (Graham, Haidt, & Nosek, Reference Graham, Haidt and Nosek2009; Horberg, Oveis, Keltner, & Cohen, Reference Horberg, Oveis, Keltner and Cohen2009; Koleva, Graham, Iyer, Ditto, & Haidt, Reference Koleva, Graham, Iyer, Ditto and Haidt2012), drugs, alcohol, and certain kinds of music (Helzer & Pizarro, Reference Helzer and Pizarro2011; Horberg et al., Reference Horberg, Oveis, Keltner and Cohen2009) – all of which are central to puritanism as defined here. However, because of its heterogeneity (Kollareth et al., Reference Kollareth, Brownell, Duran and Russell2022), the purity category is broader than puritanism as we define it. In particular, purity also includes concerns for physical contamination, often operationalized by weird or abnormal behaviors (Gray & Keeney, Reference Gray and Keeney2015; Kupfer, Inbar, & Tybur, Reference Kupfer, Inbar and Tybur2020), such as pouring urine on oneself (Chakroff, Russell, Piazza, & Young, Reference Chakroff, Russell, Piazza and Young2017), touching poop barehanded (Dungan, Chakroff, & Young, Reference Dungan, Chakroff and Young2017), or eating pizza off a dead body (Clifford, Iyengar, Cabeza, & Sinnott-Armstrong, Reference Clifford, Iyengar, Cabeza and Sinnott-Armstrong2015). We do not include this subclass of purity in our definition of puritanism because, as researchers have noted, these contamination-related concerns appear distinct from those labeled here as puritanical (see Crone, Reference Crone2022; though see sect. 6.1.1).

Why, then, do many societies develop puritanical values? Answering this question requires resolving two puzzles.

1.1. The puzzle of association

First, puritanism consists of apparently heterogenous moral concerns, governing domains as various as sex, food, clothing, self-discipline, entertainments, and ritual observance. Yet despite their heterogeneity, these moral concerns tend to co-occur and cohere in the most culturally successful moral traditions, which cover almost 80% of the world's population (Hackett & McClendon, Reference Hackett and McClendon2017) – from Hinduism (Doniger, Reference Doniger2014, pp. 363–370; Hatcher, Reference Hatcher2017; Menon, Reference Menon2013; Nag, Reference Nag1972, p. 236; Stephens, Reference Stephens1972, p. 4; Vatuk & Vatuk, Reference Vatuk and Vatuk1967, pp. 108–112) to Christianity (Bremer, Reference Bremer2009; Burke, Reference Burke1978; Dabhoiwala, Reference Dabhoiwala2012; Gaca, Reference Gaca2003; Gorski, Reference Gorski2003; Partridge & Moberg, Reference Partridge and Moberg2017; Spiegel, Reference Spiegel2020; Wagner, Reference Wagner1997) to Buddhism (Harvey, Reference Harvey2000; Keown, Reference Keown2003, pp. 78, 93; Mann, Reference Mann2011; Sterckx, Reference Sterckx2005, pp. 223–224; Stunkard, LaFleur, & Wadden, Reference Stunkard, LaFleur and Wadden1998) to Chinese religions (Brokaw, Reference Brokaw2014; Csikszentmihalyi, Reference Csikszentmihalyi, Lagerwey and Kalinowski2009; Slingerland, Reference Slingerland2014, p. 76; Suiming, Reference Suiming1998; Tiwald, Reference Tiwald and Zalta2020; Yü, Reference Yü2021, pp. 36–40, 82, 216) to Arab-Muslim societies (Garden, Reference Garden2014, pp. 83, 89, 76; Mernissi, Reference Mernissi2011; Michalak & Trocki, Reference Michalak and Trocki2006; Otterbeck & Ackfeldt, Reference Otterbeck and Ackfeldt2012, pp. 231–233; Rehman, Reference Rehman2019) and ancient Greco-Roman spiritualities (Gaca, Reference Gaca2003; Langlands, Reference Langlands2006).

This association, suggested by qualitative data, is consistent with psychological evidence. Studies find that moralizations of gluttony, sexual indulgences, lack of self-control, intoxicant use, and certain types of music, are intercorrelated (Fitouchi et al., Reference Fitouchi, André, Baumard and Nettle2022; Kurzban, Dukes, & Weeden, Reference Kurzban, Dukes and Weeden2010; Lynxwiler & Gay, Reference Lynxwiler and Gay2000; Mooijman et al., Reference Mooijman, Meindl, Oyserman, Monterosso, Dehghani, Doris and Graham2018; Quintelier, Ishii, Weeden, Kurzban, & Braeckman, Reference Quintelier, Ishii, Weeden, Kurzban and Braeckman2013; Steim & Nemeroff, Reference Steim and Nemeroff1995; Tierney et al., Reference Tierney, Hardy, Ebersole, Viganola, Clemente, Gordon and Uhlmann2021). Condemnations of lack of self-control, intoxicant use, hedonism, sexual indulgences, and immodesty are all associated with religiosity (Grubbs, Exline, Pargament, Hook, & Carlisle, Reference Grubbs, Exline, Pargament, Hook and Carlisle2015; Jacquet et al., Reference Jacquet, Pazhoohi, Findling, Mell, Chevallier and Baumard2021; Mooijman et al., Reference Mooijman, Meindl, Oyserman, Monterosso, Dehghani, Doris and Graham2018; Moon, Wongsomboon, & Sevi, Reference Moon, Wongsomboon and Sevi2021; Najjar et al., Reference Najjar, Young, Leasure, Henderson and Neighbors2016; Saroglou & Craninx, Reference Saroglou and Craninx2021; Stylianou, Reference Stylianou2004; Weeden & Kurzban, Reference Weeden and Kurzban2013), which is itself related, across countries, to the moralization of piety (Abrams, Jackson, Vonasch, & Gray, Reference Abrams, Jackson, Vonasch and Gray2020; Tamir, Connaughton, & Salazar, Reference Tamir, Connaughton and Salazar2020). At a deeper level, experimental evidence indicates that different puritanical norms are intuitively intertwined in people's mind. Experimental studies of “implicit puritanism” across cultures (N > 6,000) show that Indian, American, Australian, and English participants all implicitly associate violation of one puritanical norm (work-related self-discipline) with violations of another puritanical norm (sexual restraint), by misremembering individuals described as violating one norm as also violating the other (Tierney et al., Reference Tierney, Hardy, Ebersole, Viganola, Clemente, Gordon and Uhlmann2021).

Hence the first puzzle of puritanism: Why do moralizations of bodily pleasures, self-discipline, entertainments, clothing, and piety often develop in concert?

1.2. The puzzle of morality without cooperation

The second puzzle of puritanical morality concerns its relation to cooperation. Most evolutionary theories of morality share the ultimate hypothesis that moral cognition is an adaptation to the challenges of cooperation recurrent in human social life (Alexander, Reference Alexander1987; André, Fitouchi, Debove, & Baumard, Reference André, Fitouchi, Debove and Baumard2022; Baumard, André, & Sperber, Reference Baumard, André and Sperber2013; Boehm, Reference Boehm2012; Curry, Reference Curry, Shackelford and Hansen2016; Haidt, Reference Haidt2012; Stanford, Reference Stanford2018; Tomasello, Reference Tomasello2020). This hypothesis explains the vast majority of moral intuitions and norms found across human societies, such as condemnations of theft, murder, violence, unfairness, and the promotion of justice, loyalty, reciprocity, or respect for property and authority (Baumard, Reference Baumard2016; Boehm, Reference Boehm2012; Curry, Jones Chesters, & Van Lissa, Reference Curry, Jones Chesters and Van Lissa2019a; Hofmann, Wisneski, Brandt, & Skitka, Reference Hofmann, Wisneski, Brandt and Skitka2014; Purzycki et al., Reference Purzycki, Pisor, Apicella, Atkinson, Cohen, Henrich and Xygalatas2018).

In this context, puritanical morality appears as an “odd corner of moral life” (Haidt & Joseph, Reference Haidt and Joseph2004, p. 60). If moral cognition evolved for cooperation, moral condemnations should only target cheating behaviors, such as lying, theft, free-riding, betrayal of coalition partners, or suffering inflicted on innocent people. Yet the behaviors typically moralized by puritanical values are not, at first sight, clearly related to cooperation. For example, in medieval Christianity (Dabhoiwala, Reference Dabhoiwala2012), Neo-Confucian China (Suiming, Reference Suiming1998, p. 16), or Victorian England (Seidman, Reference Seidman1990), indulgence in sexual pleasure is condemned not only when it amounts to cheating other people in a cooperative interaction, such as in adultery,Footnote 1 but also in a range of victimless manifestations, such as in masturbation, or too frequent or licentious sex within marriage:

A huge body of teaching grew up in support of the notion that bodily desire was inherently shameful and sinful … Even in marriage, men and women had to be constantly on their guard against sinning through immoderate, unchaste, or unprocreative sex. (Dabhoiwala, Reference Dabhoiwala2012, pp. 7–8)

In moral psychology, famous vignette studies have echoed this apparent harmlessness of sexual sins, finding that American and Brazilian participants condemn “purity violations,” such as masturbating in a chicken carcass, even though these actions do not in themselves cause any harm to other individuals (Haidt et al., Reference Haidt, Koller and Dias1993; Haidt & Hersh, Reference Haidt and Hersh2001; Horberg et al., Reference Horberg, Oveis, Keltner and Cohen2009).

Similarly, puritanical values condemn immoderate indulgence in food pleasure, even when gluttony doesn't involve failing in one's duty to share food, or to respect others' property (e.g., medieval Christianity: Adamson, Reference Adamson2004; Hill, Reference Hill2011; India: Vatuk & Vatuk, Reference Vatuk and Vatuk1967; European antiquity: Coveney, Reference Coveney2006; Gaca, Reference Gaca2003). The Christian sin of gluttony, for example, condemns the failure to control the food appetite in itself – whether by eating too much, failing to wait for the proper time to eat, eating too eagerly, or craving foods that are too tasty (Adamson, Reference Adamson2004; Hill, Reference Hill2007, Reference Hill2011). Psychologists, too, observe that participants moralize inherently harmless eating practices, such as eating fatty rather than healthy foods (Fitouchi et al., Reference Fitouchi, André, Baumard and Nettle2022; Mooijman et al., Reference Mooijman, Meindl, Oyserman, Monterosso, Dehghani, Doris and Graham2018; Oakes & Slotterback, Reference Oakes and Slotterback2004; Steim & Nemeroff, Reference Steim and Nemeroff1995).

Besides food and sex, puritanical values prescribe industrious self-discipline even when idleness would be harmless and effort unproductive (Indian, American, Australian, and English participants: Tierney et al., Reference Tierney, Hardy, Ebersole, Viganola, Clemente, Gordon and Uhlmann2021; Uhlmann, Poehlman, Tannenbaum, & Bargh, Reference Uhlmann, Poehlman, Tannenbaum and Bargh2011; American, French, and South-Korean participants: Celniker et al., Reference Celniker, Gregory, Koo, Piff, Ditto and Shariff2023; early modern China: Yü, Reference Yü2021). They condemn alcohol, drugs, and gambling, when the latter are widely considered “victimless crimes” (Boyd & Richerson, Reference Boyd, Richerson, Gigerenzer and Selten2001; Ellis, Reference Ellis1988; Stylianou, Reference Stylianou2010). And their strict regulations of mundane activities, such as music, dance, or clothing appear, to our modern eyes, as needlessly austere restrictions (see Moon et al., Reference Moon, Wongsomboon and Sevi2021).

Hence the second puzzle of puritanism: If the function of morality is cooperation – as the prominence of cooperative norms in the human moral landscape suggests (Curry, Mullins, & Whitehouse, Reference Curry, Mullins and Whitehouse2019b; Hofmann et al., Reference Hofmann, Wisneski, Brandt and Skitka2014; Purzycki et al., Reference Purzycki, Pisor, Apicella, Atkinson, Cohen, Henrich and Xygalatas2018) – why do humans moralize victimless lifestyle choices with respect to sex, food, drinking, clothing, self-discipline, and ritual observance?

This apparent disconnect between puritanical morality and cooperation has sparked intense debates about the cognitive architecture of morality, opposing unitary models of moral cognition to theories dividing morality into distinct cognitive domains (Beal, Reference Beal2020; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt, Koleva, Motyl, Iyer, Wojcik and Ditto2013; Schein & Gray, Reference Schein and Gray2018). Unitary theories argue that all moral judgments are produced by a single, functionally unified cognitive mechanism. In particular, the theory of dyadic morality maintains that all moral judgments stem from perceptions of dyadic harm – that is, from perceptions that an “agent” intentionally causes suffering to a “patient” (Gray, Waytz, & Young, Reference Gray, Waytz and Young2012, Reference Gray, Schein and Ward2014; Schein & Gray, Reference Schein and Gray2015, Reference Schein and Gray2018). Other unitary theories argue that all moral judgments are outputs of fairness computations, tracking violations of mutual benefit between cooperative partners (André et al., Reference André, Fitouchi, Debove and Baumard2022; Baumard, Reference Baumard2016; Fitouchi, André, & Baumard, Reference Fitouchi, André, Baumard, Al-Shawaf and Shackelfordin press).Footnote 2 By contrast, theories based on distinct cognitive domains – such as moral foundations theory – maintain that moral cognition is composed of multiple, functionally distinct, domain-specific mechanisms, some of which track stimuli unrelated to harm or fairness (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt, Koleva, Motyl, Iyer, Wojcik and Ditto2013). In these debates, purity moralizations have appeared as critical arguments against unitary theories. If harmless behaviors can be morally condemned, scholars have argued, there must be in the mind some mechanisms that generate moral judgments despite not functioning for cooperation (Haidt, Reference Haidt2012). Accordingly, puritanical morality has so far been explained by psychological mechanisms unrelated to cooperation, such as pathogen avoidance and conflicts of reproductive interests (sect. 2).

1.3. The moral disciplining theory of puritanism

Here, we propose that puritanical morality does target cooperation, and is reducible to concerns for harm or fairness. Psychologists and evolutionary scientists have long noted that reciprocal and reputation-based cooperation require self-control – the ability to delay gratification, by resisting temptations of immediate rewards (Ainslie, Reference Ainslie2013; Axelrod, Reference Axelrod1984; Hofmann, Meindl, Mooijman, & Graham, Reference Hofmann, Meindl, Mooijman and Graham2018; Manrique et al., Reference Manrique, Zeidler, Roberts, Barclay, Walker, Samu and Raihani2021; Stevens, Cushman, & Hauser, Reference Stevens, Cushman and Hauser2005). Historians and social scientists, meanwhile, have repeatedly stressed that puritanical groups seem obsessed with the cultivation of self-control (Csikszentmihalyi, Reference Csikszentmihalyi, Lagerwey and Kalinowski2009; Dabhoiwala, Reference Dabhoiwala2012; Eisner, Reference Eisner2014; Gaca, Reference Gaca2003; Gorski, Reference Gorski2003; Luttmer, Reference Luttmer2000; Menon, Reference Menon2013; Oestreich, Oestreich, & Koenigsberger, Reference Oestreich, Oestreich and Koenigsberger1982; Rehman, Reference Rehman2019; Seidman, Reference Seidman1990; Spiegel, Reference Spiegel2020; Walzer, Reference Walzer1963, Reference Walzer1982; Weber, Reference Weber1968; Yü, Reference Yü2021). Connecting these insights, we propose that puritanism develops from folk-psychological beliefs that restraining indulgence in victimless pleasures would improve people's self-control, thus facilitating cooperative behaviors.

Our argument goes as follows. People perceive that meeting prosocial obligations often requires self-control (sect. 3.1). Refraining from violent behaviors, they perceive, sometimes requires resisting aggressive impulses. Abstaining from adultery sometimes requires resisting sexual temptations. In collective work, doing one's fair share of effort can require overcoming lazy desires. Meanwhile, people perceive, not only that cooperation requires self-control, but also that some behaviors alter self-control (sect. 3.2). They perceive that alcohol and drugs make people impulsive, precipitating antisocial behaviors – such as adultery, violence, or lazy free-riding – by impeding abilities to resist impulses. They see carnal pleasures – lust, gluttony, intoxicants, gambling – as dangerously addictive behaviors, overindulgence in which would make people slave to their urges, and unable to resist uncooperative temptations. By contrast, daily self-discipline, ascetic temperance, and regular ritual observance are perceived as improving people's self-control, thus ensuring that they remain peaceful neighbors, faithful husbands and wives, industrious workers, responsible family members, or conscientious followers. Thus, although inherently harmless, hedonistic behaviors are perceived as indirectly socially harmful. As such, they are naturally tagged as morally wrong by cognitive systems biologically evolved to detect and condemn uncooperative behaviors or threats to cooperation (sect. 3.3). Puritanical moral judgments are thus generated by the same, cooperation-based cognitive systems producing the rest of human morality.

These intuitive psychological processes, in turn, shape the cultural evolution of puritanical norms (sect. 3.4). In environments where many people want to prevent perceived antisocial effects of hedonistic impulses, people gradually invent and refine cultural technologies they perceive as efficient for disciplining other individuals to ensure social order. These technologies of moral self-discipline include ascetic rituals, modest clothes, legal regulations of entertainment such as drinking and feasting, as well as mental techniques for the self-monitoring of impulses (see sect. 6.1.2). Our account, importantly, is agnostic as to whether puritanical norms are objectively effective in improving self-control and cooperation – it rather insists on people's perceptions that they are.

In the following, we first review and examine existing accounts of puritanical morality (sect. 2). Section 3 lays out the evolutionary and psychological foundations of the moral disciplining theory (MDT) of puritanism, and reviews evidence for its assumptions. We then derive predictions from this account, review current evidence supporting them, and outline avenues for further testing (sect. 4). We finally use this theory to explain the fall of puritanism in western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) societies (sect. 5), and discuss extensions and outstanding questions for the study of puritanical values (sect. 6).

2. Existing accounts of puritanical morality

2.1. Moral foundations theory and disgust-based accounts

Moral foundations theory considers puritanical morality as an exception to the cooperative function of moral cognition (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt, Koleva, Motyl, Iyer, Wojcik and Ditto2013; Haidt, Reference Haidt2012; Haidt & Joseph, Reference Haidt and Joseph2007). According to this framework, moral cognition is composed of several domain-specific cognitive systems, most which have evolved for cooperative adaptive challenges – including harm/care, fairness/reciprocity, loyalty/betrayal, and authority/respect. The last moral system, purity/sanctity, is instead proposed to function for the nonsocial challenge of pathogen avoidance, and to emerge from disgust at the proximate level (Haidt & Joseph, Reference Haidt and Joseph2007). People driven by carnal impulses rather than spiritual motivations would be detected by this disgust-related system as “impure” and “less than human,” and thus morally condemned (Haidt & Graham, Reference Haidt and Graham2007, p. 9). Although this theory is consistent with the frequent cultural depiction of pleasure-seeking behaviors as “impure,” it seems insufficient to explain puritanical morality, for at least two reasons.

First, it is unclear that violations of puritanical standards actually trigger disgust. Initial support for this hypothesis came from “purity violation” studies, in which participants find apparently harmless behaviors (e.g., masturbating in a chicken carcass) both disgusting and morally wrong (e.g., Haidt et al., Reference Haidt, Koller and Dias1993; Haidt & Hersh, Reference Haidt and Hersh2001; Horberg et al., Reference Horberg, Oveis, Keltner and Cohen2009; Rozin, Lowery, Imada, & Haidt, Reference Rozin, Lowery, Imada and Haidt1999). However, containing more pathogen cues than the typical targets of puritanical moralizations, such vignettes appear disconnected from real-world puritanical concerns. As such, they are likely to overestimate the extent to which real-world violations of puritanical standards evoke disgust. For example, in widely cited studies, sexual lust takes the form of masturbating in a dead chicken (Haidt et al., Reference Haidt, Koller and Dias1993; Horberg et al., Reference Horberg, Oveis, Keltner and Cohen2009) or corpse-sexing (Haidt & Hersh, Reference Haidt and Hersh2001). Gluttony becomes eating one's dead dog (Haidt et al., Reference Haidt, Koller and Dias1993), or rotten meat (Rozin et al., Reference Rozin, Lowery, Imada and Haidt1999). By contrast, historical and anthropological data make clear that puritanical societies are less morally obsessed by disgusting sexualities with dead animals than with the sin of lust as the unbridled craving for sexual pleasure (Dabhoiwala, Reference Dabhoiwala2012; Gaca, Reference Gaca2003; Le Goff, Reference Le Goff1984; Mernissi, Reference Mernissi2011; Seidman, Reference Seidman1990). For example, medieval Christian moralists (e.g., Augustine, fourth to fifth centuries, Aquinas, thirteenth century) regarded the peculiar problem of the sin of lust to be “the intensity of the pleasure it offers” (Sweeney, Reference Sweeney, Newhauser and Ridyard2012, p. 96), and its resulting “unparalleled power to overwhelm reason and human will” (Dabhoiwala, Reference Dabhoiwala2012, p. 8). In the same vein, the sin of gluttony condemns the immoderate indulgence in the pleasure of eating (Adamson, Reference Adamson2004; Bynum, Reference Bynum2000; Hill, Reference Hill2007, Reference Hill2011), not the eating of rotten aliments or animal corpses. In fact, pleasurable aliments (affording gluttony) are almost by definition aliments that are not disgusting. In line with these ideas, when participants are asked to themselves generate sinful or lustful scenarios, they overwhelmingly mention pathogen-free behaviors (e.g., stripping) (Gray & Keeney, Reference Gray and Keeney2015).

Aside from lust and gluttony, moralizations of intemperance, lack of self-discipline, and impiety also seem unrelated to disgust. These behaviors do not involve pathogen cues at all. Accordingly, maintaining that disgust explains their condemnation has required to argue that this emotion is triggered not only by pathogen cues, but also by “spiritually” impure behaviors, that “degrade” the elevated nature of the human soul or remind humans of their “animal nature” (Haidt & Graham, Reference Haidt and Graham2007; Rozin et al., Reference Rozin, Lowery, Imada and Haidt1999, Reference Rozin, Haidt, McCauley, Lewis, Haviland-Jones and Barrett2008; Rozin & Haidt, Reference Rozin and Haidt2013) – an often contested theory (Bloom, Reference Bloom2013; Royzman & Sabini, Reference Royzman and Sabini2001; Tybur, Lieberman, Kurzban, & DeScioli, Reference Tybur, Lieberman, Kurzban and DeScioli2013). As many researchers have noted, self-reports of being “disgusted” by “spiritual impurities” (Ritter, Preston, Salomon, & Relihan-Johnson, Reference Ritter, Preston, Salomon and Relihan-Johnson2016) do not reliably demonstrate that the cognitive system of disgust is actually activated. The lay meaning of the term “disgust” is difficult to disentangle from “anger” or “contempt” (Herz & Hinds, Reference Herz and Hinds2013; Nabi, Reference Nabi2002; Piazza, Landy, Chakroff, Young, & Wasserman, Reference Piazza, Landy, Chakroff, Young, Wasserman, Strohminger and Kumar2018), and people likely use the term metaphorically to communicate their disapproval (Armstrong, Wilbanks, Leong, & Hsu, Reference Armstrong, Wilbanks, Leong and Hsu2020; Bloom, Reference Bloom2004; Nabi, Reference Nabi2002; Royzman & Kurzban, Reference Royzman and Kurzban2011; Royzman & Sabini, Reference Royzman and Sabini2001). In line with this idea, pathogen-free violations of “spiritual purity” are not associated with the facial expression of disgust (Franchin, Geipel, Hadjichristidis, & Surian, Reference Franchin, Geipel, Hadjichristidis and Surian2019; Ritter et al., Reference Ritter, Preston, Salomon and Relihan-Johnson2016); do not elicit a disgust-related phenomenology (nausea, gagging, loss of appetite), nor action tendency (desire to move away) (Royzman, Atanasov, Landy, Parks, & Gepty, Reference Royzman, Atanasov, Landy, Parks and Gepty2014); and are not or negligibly associated with reporting being “grossed-out” (Kollareth et al., Reference Kollareth, Brownell, Duran and Russell2022; Kollareth & Russell, Reference Kollareth and Russell2019) – the lay term more aptly capturing the cognitively strict sense of disgust (Herz & Hinds, Reference Herz and Hinds2013; Nabi, Reference Nabi2002).

Second, disgust-based accounts of puritanism rely on the premise that simply perceiving an action as disgusting is sufficient to judge it immoral. As researchers have noted, however, many behaviors are disgusting without being immoral (Kayyal, Pochedly, McCarthy, & Russell, Reference Kayyal, Pochedly, McCarthy and Russell2015; Piazza et al., Reference Piazza, Landy, Chakroff, Young, Wasserman, Strohminger and Kumar2018; Pizarro, Inbar, & Helion, Reference Pizarro, Inbar and Helion2011; Schein et al., Reference Schein, Ritter and Gray2016). It seems, moreover, evolutionarily unclear why disgust should have acquired such a secondary moralizing function (Fitouchi et al., Reference Fitouchi, André, Baumard, Al-Shawaf and Shackelfordin press), and the experimental evidence seems overall to cast doubt on this possibility (see Piazza et al. [Reference Piazza, Landy, Chakroff, Young, Wasserman, Strohminger and Kumar2018], for an extensive review). In particular, a meta-analysis (Landy & Goodwin, Reference Landy and Goodwin2015), highly powered replications (Ghelfi et al., Reference Ghelfi, Christopherson, Urry, Lenne, Legate, Fischer and Sullivan2020; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Wortman, Cheung, Hein, Lucas, Donnellan and Narr2016), and recent studies (Jylkkä, Härkönen, & Hyönä, Reference Jylkkä, Härkönen and Hyönä2021) strongly suggest that feelings of disgust do not increase moral condemnation, nor cause moralization of otherwise morally neutral actions. Relatedly, correlations between disgust-sensitivity and condemnations of sex- and purity-related behaviors (Crawford, Inbar, & Maloney, Reference Crawford, Inbar and Maloney2014; Horberg et al., Reference Horberg, Oveis, Keltner and Cohen2009; Inbar, Pizarro, Knobe, & Bloom, Reference Inbar, Pizarro, Knobe and Bloom2009) have been found to disappear when perceptions of harm are controlled for (Schein et al., Reference Schein, Ritter and Gray2016; see also Gray & Schein, Reference Gray and Schein2016; Gray, Schein, & Ward, Reference Gray, Schein and Ward2014), and to partly result from the more general effect of affective states (not only disgust) on a wide range of (not only moral) judgments (Cheng, Ottati, & Price, Reference Cheng, Ottati and Price2013; Landy & Piazza, Reference Landy and Piazza2017).

2.2. Self-serving norms and conflicts of sexual strategies

An important framework posits that moral cognition evolved not to promote cooperation, but to advance the condemner's self-interest, by recruiting allies to condemn enemies, coordinating side-taking in conflicts, and promoting moral norms advantageous to oneself (DeScioli, Reference DeScioli2016; DeScioli & Kurzban, Reference DeScioli and Kurzban2009, Reference DeScioli and Kurzban2013; DeScioli, Massenkoff, Shaw, Petersen, & Kurzban, Reference DeScioli, Massenkoff, Shaw, Petersen and Kurzban2014; Petersen, Reference Petersen2018; Sznycer et al., Reference Sznycer, Lopez Seal, Sell, Lim, Porat, Shalvi and Tooby2017; Tooby & Cosmides, Reference Tooby, Cosmides, Hogh-Olesen, Boesch and Cosmides2010). Within this framework, researchers argue that some puritanical norms emerge from self-serving attempts by some individuals to promote their reproductive interests at the expense of others' (Kurzban et al., Reference Kurzban, Dukes and Weeden2010; Weeden & Kurzban, Reference Weeden and Kurzban2016; Weeden, Cohen, & Kenrick, Reference Weeden, Cohen and Kenrick2008). The reproductive religiosity model argues that a high level of promiscuity in the environment threatens monogamous individuals' ability to reap the benefits of their committed, parentally investing reproductive strategy, by increasing the risk of cuckoldry or mate-poaching (Weeden & Kurzban, Reference Weeden and Kurzban2016). Monogamous individuals, thus, have an interest in normatively curbing sexual promiscuity. Researchers also argue that males' attempts to control female sexuality explain values of female chastity and modesty, and restrictions aimed at increasing paternity certainty, such as veiling, virginity tests, female claustration, and menstrual taboos (Becker, Reference Becker2019; Blake, Fourati, & Brooks, Reference Blake, Fourati and Brooks2018; Dickemann, Reference Dickemann, Alexander and Tinkle1981; Pazhoohi, Lang, Xygalatas, & Grammer, Reference Pazhoohi, Lang, Xygalatas and Grammer2017a; Strassmann, Reference Strassmann1992; Strassmann et al., Reference Strassmann, Kurapati, Hug, Burke, Gillespie, Karafet and Hammer2012).

These accounts are not incompatible with our proposal. Mate-guarding surely underlies many sexual restrictions (Strassmann et al., Reference Strassmann, Kurapati, Hug, Burke, Gillespie, Karafet and Hammer2012) and is consistent with the frequent double standard favoring men in the moralization of sexuality (Broude & Greene, Reference Broude and Greene1976; Dabhoiwala, Reference Dabhoiwala2012). Consistent with the reproductive religiosity model, monogamous individuals more harshly oppose sexual promiscuity (Weeden & Kurzban, Reference Weeden and Kurzban2016) and its facilitators (e.g., drugs; Kurzban et al., Reference Kurzban, Dukes and Weeden2010; Quintelier et al., Reference Quintelier, Ishii, Weeden, Kurzban and Braeckman2013), and seem to use religion to facilitate and encourage monogamous pair-bonding (Baumard & Chevallier, Reference Baumard and Chevallier2015; Jacquet et al., Reference Jacquet, Pazhoohi, Findling, Mell, Chevallier and Baumard2021; Moon, Reference Moon2021; Moon, Krems, Cohen, & Kenrick, Reference Moon, Krems, Cohen and Kenrick2019; Weeden et al., Reference Weeden, Cohen and Kenrick2008; Weeden & Kurzban, Reference Weeden and Kurzban2013).

However, these accounts fail to sufficiently explain the more general condemnation of hedonic excesses beyond sexuality, such as gluttony (Hill, Reference Hill2011; Steim & Nemeroff, Reference Steim and Nemeroff1995), drinking, harmless idleness (Tierney et al., Reference Tierney, Hardy, Ebersole, Viganola, Clemente, Gordon and Uhlmann2021), or general lack of self-discipline (Mooijman et al., Reference Mooijman, Meindl, Oyserman, Monterosso, Dehghani, Doris and Graham2018) – sexual lust is only one of the many pleasure-seeking tendencies that puritanical morality condemns. They also do not account for the condemnation of bodily pleasures as intrinsically sinful, even when they are truly harmless to males or monogamous strategists, such as in frequent sexuality between monogamous, married partners (e.g., Dabhoiwala, Reference Dabhoiwala2012, pp. 7–9; Seidman, Reference Seidman1990; Suiming, Reference Suiming1998, p. 16), or in solitary masturbation (Seidman, Reference Seidman1990). Besides, puritanical societies moralize not only female lust but male sexual desires as well – an observation inconsistent with the mate-guarding hypothesis (Muslim Zanzibar: Beckmann, Reference Beckmann2010; medieval and early modern Europe: Dabhoiwala, Reference Dabhoiwala2012, p. 8; McIntosh, Reference McIntosh2002, pp. 73–74; Victorian England: Seidman, Reference Seidman1990).

Although manipulative use of moral discourse is surely used to justify oppressive norms (Strassmann et al., Reference Strassmann, Kurapati, Hug, Burke, Gillespie, Karafet and Hammer2012), and advance condemners' self-interests (DeScioli et al., Reference DeScioli, Massenkoff, Shaw, Petersen and Kurzban2014; Sznycer et al., Reference Sznycer, Lopez Seal, Sell, Lim, Porat, Shalvi and Tooby2017), we propose, in the following, that people genuinely perceive puritanical norms as mutually beneficial in the social contexts in which they prevail.

3. The moral disciplining theory of puritanism

We propose that hedonistic behaviors, although inherently victimless, are condemned because they are perceived as indirectly favoring uncooperative behaviors (e.g., aggression, infidelity, free-riding), by altering people's self-control. This hypothesis assumes that people perceive cooperation as requiring self-control (sect. 3.1); that people perceive hedonistic behaviors, such as intoxicant use, bodily pleasures, and undisciplined lifestyles, as reducing people's self-control (sect. 3.2); and that moral cognition is triggered not only by intrinsic instances of cheating, but also by behaviors perceived to indirectly and probabilistically favor socially harmful outcomes (sect. 3.3).

3.1. People perceive that cooperation requires self-control

Before reviewing evidence that people perceive self-control as necessary for cooperative behavior (sect. 3.1.3), we argue that this intuition is somewhat justified: Central forms of human cooperation – reciprocal and reputation-based cooperation – objectively require delaying gratification (sects. 3.1.1 and 3.1.2). This objective relationship between cooperation and self-control allows explaining why people perceive that cooperation requires self-control in the first place.

3.1.1. Reciprocal and reputation-based cooperation require delaying gratification

Cooperation refers to any behavior that benefits another individual (the recipient), and the evolutionary function of which is, at least in part, to benefit the recipient (West, Griffin, & Gardner, Reference West, Griffin and Gardner2007, Reference West, El Mouden and Gardner2011). Some types of cooperation provide immediate inclusive fitness benefits to the actor. This is the case of kin altruism, whereby the actor automatically increases his indirect fitness (Hamiltron, Reference Hamiltron1964). This is also the case of by-product mutualisms (West, El Mouden, & Gardner, Reference West, El Mouden and Gardner2011), or cooperation for “shared interests” (West, Cooper, Ghoul, & Griffin, Reference West, Cooper, Ghoul and Griffin2021), whereby the actor benefits the recipient as a by-product of pursing his own immediate self-interest (e.g., cooperative hunting in social carnivores; Leimar & Connor, Reference Leimar, Connor and Hammerstein2003; Leimar & Hammerstein, Reference Leimar and Hammerstein2010).

When the actor's and the recipient's immediate interests are not fully aligned, however, cooperation requires the actor to invest an immediate cost (to benefit the recipient), that is rewarded only in the future, by greater benefit-provision (or reduced cost-infliction) from the recipient or third parties – such as through direct reciprocity (Axelrod, Reference Axelrod1984; Trivers, Reference Trivers1971), indirect reciprocity (Nowak & Sigmund, Reference Nowak and Sigmund2005; Panchanathan & Boyd, Reference Panchanathan and Boyd2004), or partner choice (Barclay, Reference Barclay2013; Roberts, Reference Roberts2020). In the iterated Prisoner's Dilemma, for example, reciprocal cooperation yields higher payoff than defection only in the long run, by securing partners' willingness to reciprocate in subsequent rounds – in the immediate present of each round, cheating pays more than cooperating (Axelrod, Reference Axelrod1984; Axelrod & Hamilton, Reference Axelrod and Hamilton1981). Using evolutionary simulations, Roberts (Reference Roberts2020) shows that the same holds for cooperation under reputation-based partner choice: Cooperation is adaptive when the cost of renouncing the immediate benefit of cheating is exceeded, in the long run, by the increased probability of being chosen as a partner in subsequent interactions. In other words, because people selectively associate with trustworthy partners, a good reputation can be understood as a capital that yields future benefits at each time step of the rest of an individual's life. Damaging this capital by exploiting others brings immediate benefits (e.g., more resources, sexual opportunities, less effort), yet deprives oneself of all the benefits that a good reputation could have brought at each later time-point, by attracting others' cooperative investments (Lie-Panis & André, Reference Lie-Panis and André2022).

Accordingly, scholars have widely noted that reciprocal and reputation-based cooperation require delaying gratification: Individuals must renounce the immediate, smaller reward of cheating to secure the future, larger benefits of cooperating (Axelrod, Reference Axelrod2006; Frank, Reference Frank1988; Manrique et al., Reference Manrique, Zeidler, Roberts, Barclay, Walker, Samu and Raihani2021; Roberts, Reference Roberts2020; Stevens et al., Reference Stevens, Cushman and Hauser2005). Lie-Panis and André (Reference Lie-Panis and André2022) develop a formal understanding of this idea. In their model, individuals are characterized by a discount rate, and engage in numerous trust games during their lifetime, with a certain probability of being observed by others, who transmit reputational information impacting future partner choice. At equilibrium in their model, individuals who cooperate are those who are sufficiently future-oriented, that is, who discount the future benefit of having a good reputation in the rest of their life little enough for this benefit to outweigh the immediate cost of cooperation.

3.1.2. Cooperation and self-control at the proximate level

In line with the fact that reciprocal and reputation-based cooperation ultimately require delaying gratification, psychologists have long noted that self-control – the ability to resist temptations of immediate rewards – is likely involved in cooperative decision making (Ainslie, Reference Ainslie2013; Hofmann et al., Reference Hofmann, Meindl, Mooijman and Graham2018; Manrique et al., Reference Manrique, Zeidler, Roberts, Barclay, Walker, Samu and Raihani2021; Stevens et al., Reference Stevens, Cushman and Hauser2005). For example, when faced with an attractive mating opportunity, avoiding cheating one's partner requires resisting temptations of immediate sexual pleasure (see Gailliot & Baumeister, Reference Gailliot and Baumeister2007). By renouncing this immediate reward, one secures the long-term benefit of preserving one's pair-bonding relationship – a particular type of cooperative interaction (Gurven, Winking, Kaplan, von Rueden, & McAllister, Reference Gurven, Winking, Kaplan, von Rueden and McAllister2009) – as well as one's reputation as a trustworthy partner. Meeting obligations to share resources with others, similarly, requires resisting the immediate reward of consuming these resources for oneself (Hofmann et al., Reference Hofmann, Meindl, Mooijman and Graham2018; Sebastián-Enesco & Warneken, Reference Sebastián-Enesco and Warneken2015). By resisting this temptation, one secures the larger, future benefits of ensuring reciprocal help, as well as a good reputation. Similarly, avoiding interpersonal conflicts sometimes requires overriding aggressive impulses (see Barton-Crosby & Hirtenlehner, Reference Barton-Crosby and Hirtenlehner2021); and doing one's part in collaborative work requires renouncing immediate leisure or procrastination. We call (1) “temptations to cheat” these impulses for immediate rewards (e.g., food, sex, rest) that conflict with prosocial obligations, and (2) “moral self-control” the resistance to these temptations to cheat (following Hofmann et al., Reference Hofmann, Meindl, Mooijman and Graham2018).

Converging lines of evidence demonstrate this importance of self-control for a wide range of cooperative behaviors. Performance on a delay-of-gratification task predicts children's propensity to share resources with others, after controlling for age (Sebastián-Enesco & Warneken, Reference Sebastián-Enesco and Warneken2015). Focusing on the future rather than immediate consequences of their behaviors makes participants more likely to share with others (Sjåstad, Reference Sjåstad2019), and less likely to behave unethically (Hershfield, Cohen, & Thompson, Reference Hershfield, Cohen and Thompson2012; van Gelder, Hershfield, & Nordgren, Reference van Gelder, Hershfield and Nordgren2013; Vonasch & Sjåstad, Reference Vonasch and Sjåstad2021). Consistent with a trade-off between the immediate benefit of cheating and its future reputational cost, these associations between cooperation and future-orientation are mediated by reputational concern (Sjåstad, Reference Sjåstad2019; Vonasch & Sjåstad, Reference Vonasch and Sjåstad2021). Disrupting participants' right lateral prefrontal cortex – implied in the self-control of impulses for instant rewards (Kober et al., Reference Kober, Mende-Siedlecki, Kross, Weber, Mischel, Hart and Ochsner2010) – makes participants more likely to cheat in cooperative interactions (Knoch & Fehr, Reference Knoch and Fehr2007; Knoch, Schneider, Schunk, Hohmann, & Fehr, Reference Knoch, Schneider, Schunk, Hohmann and Fehr2009; Ruff, Ugazio, & Fehr, Reference Ruff, Ugazio and Fehr2013; Soutschek, Sauter, & Schubert, Reference Soutschek, Sauter and Schubert2015; Strang et al., Reference Strang, Gross, Schuhmann, Riedl, Weber and Sack2015). Following 1,000 children from birth to age 32, Moffitt et al. (Reference Moffitt, Arseneault, Belsky, Dickson, Hancox, Harrington and Caspi2011) show that children with poor self-control are more likely to be convicted of a criminal offense as adults, after controlling for social class origins and IQ. Meta-analytic evidence confirms that low self-control is associated with criminal behaviors (Vazsonyi, Mikuška, & Kelley, Reference Vazsonyi, Mikuška and Kelley2017), lower propensity to forgive others and refrain from retaliation (Burnette et al., Reference Burnette, Davisson, Finkel, Van Tongeren, Hui and Hoyle2014; Liu & Li, Reference Liu and Li2020), and poorer interpersonal functioning (e.g., loyalty) (de Ridder, Lensvelt-Mulders, Finkenauer, Stok, & Baumeister, Reference de Ridder, Lensvelt-Mulders, Finkenauer, Stok and Baumeister2012). Low self-control predicts greater propensity to deceive others to obtain more benefits (Fan, Ren, Zhang, Xiao, & Zhong, Reference Fan, Ren, Zhang, Xiao and Zhong2020), lower likelihood to keep promises in relationships (Peetz & Kammrath, Reference Peetz and Kammrath2011), as well as uncooperative behaviors in the workplace (e.g., low accommodation of coworkers' needs) (Cohen, Panter, Turan, Morse, & Kim, Reference Cohen, Panter, Turan, Morse and Kim2014; Restubog, Garcia, Wang, & Cheng, Reference Restubog, Garcia, Wang and Cheng2010). Regarding sexual cheating, low conscientiousness – a construct related to self-control (Duckworth & Seligman, Reference Duckworth and Seligman2017) – predicts greater likelihood of infidelity in men and women across 52 countries of 10 world regions (Schmitt, Reference Schmitt2004; see also Pronk, Karremans, & Wigboldus, Reference Pronk, Karremans and Wigboldus2011). And studies suggest that intensity of sexual desire, as well as tendencies to notice attractive alternative partners, predict greater infidelity among people with low, but not high dispositional self-control (Brady, Baker, & Miller, Reference Brady, Baker and Miller2020; McIntyre, Barlow, & Hayward, Reference McIntyre, Barlow and Hayward2015).

Despite this wealth of evidence, the self-control requirement of cooperation has been questioned by results from economic games, where meta-analytic evidence finds no association between self-control and cooperation (Thielmann, Spadaro, & Balliet, Reference Thielmann, Spadaro and Balliet2020). Studies also found that American participants cooperate more when forced to decide quickly than when forced to delay their decision – suggesting that cooperation in economic games, rather than requiring self-control, may be spontaneous and effortless (Rand, Reference Rand2016, Reference Rand2017; Rand, Greene, & Nowak, Reference Rand, Greene and Nowak2012). However, this “intuitive cooperation” effect failed to replicate in several, highly powered replications (Bouwmeester et al., Reference Bouwmeester, Verkoeijen, Aczel, Barbosa, Bègue, Brañas-Garza and Wollbrant2017; Camerer et al., Reference Camerer, Dreber, Holzmeister, Ho, Huber, Johannesson and Wu2018; Fromell, Nosenzo, & Owens, Reference Fromell, Nosenzo and Owens2020; Isler, Yilmaz, & John Maule, Reference Isler, Yilmaz and John Maule2021). Recent evidence indicates that, although cooperating in economic games may be prosocial individuals' spontaneous impulse, the reverse is true for more selfish individuals, in which deliberation increases cooperation – consistent with a role of self-control (Alós-Ferrer & Garagnani, Reference Alós-Ferrer and Garagnani2020; Andrighetto, Capraro, Guido, & Szekely, Reference Andrighetto, Capraro, Guido and Szekely2020; Nockur & Pfattheicher, Reference Nockur and Pfattheicher2021; Yamagishi et al., Reference Yamagishi, Matsumoto, Kiyonari, Takagishi, Li, Kanai and Sakagami2017). As Thielmann et al. (Reference Thielmann, Spadaro and Balliet2020) note, this moderation by prosocial disposition may have obscured the relationship between self-control and cooperation in their meta-analysis of economic games (pp. 62–63). Field experiments also suggest that economic games underestimate the involvement of self-control in real-life cooperative decisions. Studying Brazilian fishermen living from their catch from a common lake, Fehr and Leibbrandt (Reference Fehr and Leibbrandt2011) found that, while impulsivity was not associated with lower cooperation in an economic game, it did predict likelihood to free-ride on the common-pool resource in real life.

3.1.3. People perceive that cooperation requires self-control

Our account of puritanism assumes that people intuitively perceive this self-control requirement of cooperation – a premise that is well supported. Lie-Panis and André (Reference Lie-Panis and André2022) show that, because ability to delay gratification enables higher levels of cooperation, it can evolve into a credible signal of trustworthiness. Psychological evidence confirms that, in interaction with strangers as well as in established relationships, people infer others' self-control from their behavior, and expect individuals they perceive as more self-controlled to behave more cooperatively (Buyukcan-Tetik & Pronk, Reference Buyukcan-Tetik and Pronk2021; Buyukcan-Tetik, Finkenauer, Siersema, Vander Heyden, & Krabbendam, Reference Buyukcan-Tetik, Finkenauer, Siersema, Vander Heyden and Krabbendam2015; Gai & Bhattacharjee, Reference Gai and Bhattacharjee2022; Gomillion, Lamarche, Murray, & Harris, Reference Gomillion, Lamarche, Murray and Harris2014; Koval, VanDellen, Fitzsimons, & Ranby, Reference Koval, VanDellen, Fitzsimons and Ranby2015; Peetz & Kammrath, Reference Peetz and Kammrath2013; Righetti & Finkenauer, Reference Righetti and Finkenauer2011). People's intuitions about a good moral character include traits arguably related to self-control, such as being principled or responsible (Goodwin, Reference Goodwin2015; Goodwin, Piazza, & Rozin, Reference Goodwin, Piazza and Rozin2013). And many societies consider self-control, self-discipline, or self-restraint, as key virtues inherent to a good moral character (e.g., Lybian Bedouins: Abu-Lughod, Reference Abu-Lughod2016, pp. 90–93; Buddhism: Clark, Reference Clark1932, pp. 86–88; Goodman, Reference Goodman and Zalta2017; Confucianism: Csikszentmihalyi, Reference Csikszentmihalyi and Zalta2020; Tiwald, Reference Tiwald and Zalta2020; Sunni Islam: el-Aswad, Reference el-Aswad and Leeming2014; Wolof: Irvine, Reference Irvine1974, pp. 126–127; Zanzibar: Beckmann, Reference Beckmann2010, p. 620; Christianity: Spiegel, Reference Spiegel2020).

3.2. People perceive that some behaviors alter self-control

People, thus, intuit that cooperation requires self-control. We argue that puritanical moral judgments emerge from the interaction of this intuition with folk-psychological beliefs that some behaviors alter self-control. These behaviors include consuming intoxicants (e.g., alcohol, drugs), exposing oneself to tempting environments (e.g., immodest clothes, unruly music and dances), overindulging in potentially addictive pleasures (e.g., food, sex, intoxicants), or pursuing undisciplined lifestyles (e.g., intemperance, idleness, lack of ritual observance). The moral disciplining theory posits that these behaviors are moralized when perceived as undermining people's ability to control their impulses, to the point of endangering compliance with their cooperative obligations. This section characterizes the folk-psychological beliefs which, we propose, underlie puritanical moral judgments.

3.2.1. Lay theories of modifiers of state-self-control

Some behaviors of the puritanical constellation, we argue, are perceived as altering self-control as a state – that is, the ability to resist temptation in a given moment. We call them “modifiers of state-self-control.”

Intoxicants. A first perceived modifier of state-self-control is intoxicant use. Psychological evidence shows that people widely believe alcohol to cause loss of self-control (Brett, Leavens, Miller, Lombardi, & Leffingwell, Reference Brett, Leavens, Miller, Lombardi and Leffingwell2016; Critchlow, Reference Critchlow1986; Leigh, Reference Leigh1987). Studies similarly suggest that people perceive drug use as enhancing short-term sexual impulses (Quintelier et al., Reference Quintelier, Ishii, Weeden, Kurzban and Braeckman2013). These lay theories likely stem from observation of intoxicants' objective psychological effects. Alcohol actually impairs the inhibition of impulses (Heatherton & Wagner, Reference Heatherton and Wagner2011), narrows attention to cues of immediate rewards – an effect known as “alcohol myopia” (Giancola, Josephs, Parrott, & Duke, Reference Giancola, Josephs, Parrott and Duke2010) – , and fuels a range of impulsive behaviors (e.g., reactive aggression: Duke, Smith, Oberleitner, Westphal, & McKee, Reference Duke, Smith, Oberleitner, Westphal and McKee2018; Gan, Sterzer, Marxen, Zimmermann, & Smolka, Reference Gan, Sterzer, Marxen, Zimmermann and Smolka2015; Parrott & Eckhardt, Reference Parrott and Eckhardt2018; sexual impulsivity: Rehm, Shield, Joharchi, & Shuper, Reference Rehm, Shield, Joharchi and Shuper2012; economic impulsivity: Schilbach, Reference Schilbach2019). Consumption of drugs is similarly associated with impulsivity (Duke et al., Reference Duke, Smith, Oberleitner, Westphal and McKee2018; Nemoto, Iwamoto, Morris, Yokota, & Wada, Reference Nemoto, Iwamoto, Morris, Yokota and Wada2007; Weafer, Mitchell, & de Wit, Reference Weafer, Mitchell and de Wit2014).

The moral disciplining theory thus posits that intoxicants are moralized because they are perceived as favoring uncooperative behaviors, such as aggression, infidelity, and general negligence of obligations, by leading people to lose control over immediate impulses, and fueling disregard of future consequences. This hypothesis contrasts with existing accounts, which ignore cooperative concerns in the moralization of intoxicants, by arguing that their moralization stems from disgust-based concerns for the “purity of the soul” (Clifford et al., Reference Clifford, Iyengar, Cabeza and Sinnott-Armstrong2015; Henderson & Dressler, Reference Henderson and Dressler2019; Horberg et al., Reference Horberg, Oveis, Keltner and Cohen2009; Silver, Reference Silver2020), or from exclusively selfish attempts of monogamous strategists to limit sexual promiscuity specifically (Kurzban et al., Reference Kurzban, Dukes and Weeden2010).

Immodesty as cue exposure. Beside intoxicants, people perceive that self-control is also threatened by exposure to stimuli triggering short-term-oriented impulses – an effect called cue exposure (Heatherton & Wagner, Reference Heatherton and Wagner2011). Animal brains evolved reward systems tracking stimuli contributing to reproductive success (e.g., food items, sexual opportunities). Environmental cues predicting such items' availability in the immediate environment (e.g., sexual cues, appetizing smell) are thus rapidly learned and imbued with “wanting” properties (Duckworth, Gendler, & Gross, Reference Duckworth, Gendler and Gross2016a; Hyman, Reference Hyman2007; Kringelbach & Berridge, Reference Kringelbach and Berridge2009). Exposure to these cues thus generates strong urges to consume the reward in the here and now, pushing individuals toward immediate gratification at the expense of long-term goals (Boswell & Kober, Reference Boswell and Kober2016; Demos, Heatherton, & Kelley, Reference Demos, Heatherton and Kelley2012; Fujita, Reference Fujita2011; Heatherton & Wagner, Reference Heatherton and Wagner2011).

People have a folk-understanding of cue exposure. Early in development, children understand that distracting their attention away from tempting cues (e.g., the marshmallow in front of them) allows them to delay gratification more easily (Carlson & Beck, Reference Carlson, Beck, Winsler, Fernyhough and Montero2001; Mischel & Mischel, Reference Mischel and Mischel1983; Peake, Hebl, & Mischel, Reference Peake, Hebl and Mischel2002). Also witnessing this folk-understanding, people develop “situational” strategies for self-control, rearranging their environment upstream (e.g., by not storing tempting snacks at home) to prevent short-term impulses to be triggered by cue exposure (Duckworth et al., Reference Duckworth, Gendler and Gross2016a; Duckworth, White, Matteucci, Shearer, & Gross, Reference Duckworth, White, Matteucci, Shearer and Gross2016b; Milyavskaya, Saunders, & Inzlicht, Reference Milyavskaya, Saunders and Inzlicht2021). This folk-understanding, we argue, has moral consequences when cue exposure is perceived as endangering, not personal self-control (e.g., resisting sugar to preserve health), but moral self-control (resisting impulses to refrain from cheating).

This allows explaining another part of the puritanical constellation – the condemnation of immodesty. Behaviors condemned as immodest by puritanical standards typically involve emission of stimuli likely perceived as triggering impulses, thus favoring harmful self-control failures. Immodest clothing reveals cues of female fertility or sexual interest, such as body curves, skin, hair, or eyes (Pazhoohi, Reference Pazhoohi2016; Pazhoohi & Hosseinchari, Reference Pazhoohi and Hosseinchari2014). Exposure to these cues is known to alter males' state-self-control, by triggering their reward systems and sexual appetite (Platek & Singh, Reference Platek and Singh2010; Spicer & Platek, Reference Spicer and Platek2010; Symons, Reference Symons, Ambramson and Pinkerton1995), and increasing their preference for immediate over delayed rewards (Kim & Zauberman, Reference Kim and Zauberman2013; Wilson & Daly, Reference Wilson and Daly2004). Studies also suggest that exposure to sexual cues increases males' propensity to engage in manipulative and coercive behaviors to obtain sexual gratification – and thus to facilitate, not only self-control failures in general, but also moral self-control failures (Ariely & Loewenstein, Reference Ariely and Loewenstein2006).

Prescriptions of modesty, we thus argue, are another strategy – besides prohibition of intoxicants – for preventing self-control failures with socially harmful effects. Immodest clothing and behaviors are moralized because, by increasing cue exposure, they are seen as increasing the probability that people – especially males – lose control over impulses, thereby favoring antisocial behaviors such as sexual aggression, conflicts, adultery, or premarital sex.Footnote 3 Just as people remove tempting snacks from their environment when feeling unable to resist them, societies can deem mutually beneficial, when fearing the fragility of their members' self-control (see sect. 5), to remove tempting stimuli from their environment to prevent uncooperative behaviors.

This hypothesis contrasts with existing accounts of modesty norms, which mainly regard them as selfish attempts of males to guard their mates (Dickemann, Reference Dickemann, Alexander and Tinkle1981; Pazhoohi et al., Reference Pazhoohi, Lang, Xygalatas and Grammer2017a). Although males' mate-guarding interests likely contribute to these norms' attractiveness, we propose that moralization of modesty also emerge from more widely shared concern for the general social harm (e.g., conflicts, aggressions, infidelity) that may result from failures to control sexual impulses.

3.2.2. Lay theories of modifiers of trait-self-control

Other behaviors of the puritanical constellation, we argue, are perceived as altering self-control as a trait – that is, as the stable psychological disposition to resist temptations across situations. We term them “modifiers of trait-self-control.”

Immoderate indulgence in bodily pleasures. Moralizations of victimless bodily pleasures, we argue, stem from perceptions that excessively or too frequently indulging in bodily pleasures would decrease trait-self-control. Such beliefs may be grounded in experience: The bodily pleasures typically condemned by puritanical standards generate common addictions, such as food addictions (Volkow, Wang, & Baler, Reference Volkow, Wang and Baler2011, Reference Volkow, Wise and Baler2017), sexual addictions (Farré et al., Reference Farré, Fernández-Aranda, Granero, Aragay, Mallorquí-Bague, Ferrer and Jiménez-Murcia2015; Karila et al., Reference Karila, Wery, Weinstein, Cottencin, Petit, Reynaud and Billieux2014), alcohol addictions (Vengeliene, Bilbao, Molander, & Spanagel, Reference Vengeliene, Bilbao, Molander and Spanagel2008), drug addictions (Baler & Volkow, Reference Baler and Volkow2007), or gambling disorders (Farré et al., Reference Farré, Fernández-Aranda, Granero, Aragay, Mallorquí-Bague, Ferrer and Jiménez-Murcia2015) – addiction being widely viewed as a disruption of self-control (Baler & Volkow, Reference Baler and Volkow2007; see also Vonasch, Clark, Lau, Vohs, & Baumeister, Reference Vonasch, Clark, Lau, Vohs and Baumeister2017). Researchers have long noted the potent reinforcement learning associated with consumption of bodily pleasures or intoxicants. Past experience with such a reward (e.g., energy-rich food) increases the motivational drive (“wanting”) elicited by future exposure to it, making harder the future self-control of the associated impulse (e.g., food craving; Baler & Volkow, Reference Baler and Volkow2007; Story, Vlaev, Seymour, Darzi, & Dolan, Reference Story, Vlaev, Seymour, Darzi and Dolan2014; Volkow, Wise, & Baler, Reference Volkow, Wise and Baler2017).

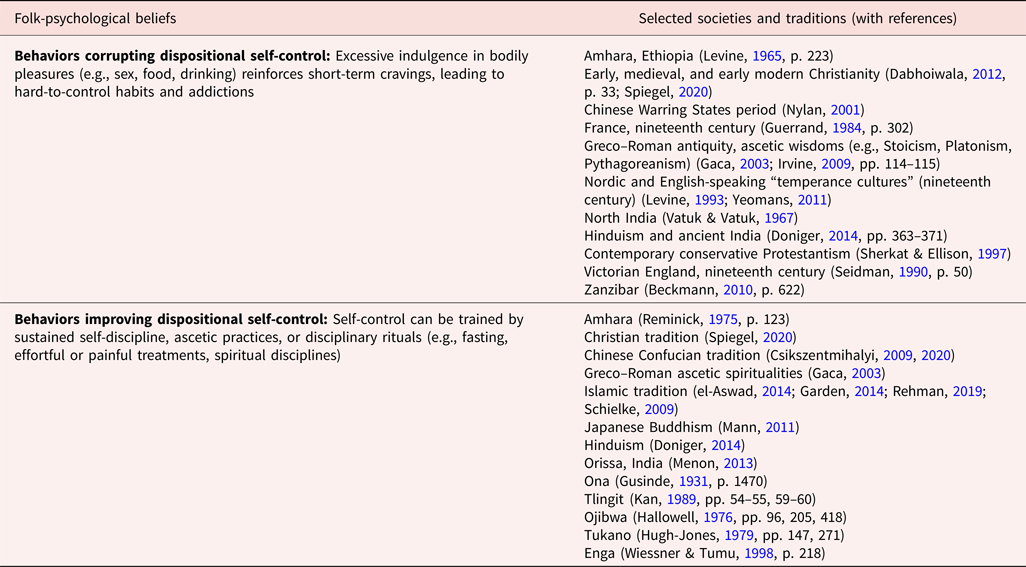

Accordingly, a widespread belief seems to be that the more one indulges in bodily pleasures, the more their temptations become hard to resist. A significant share of people believes that pornography (Grubbs, Grant, & Engelman, Reference Grubbs, Grant and Engelman2018a; Grubbs, Kraus, & Perry, Reference Grubbs, Kraus and Perry2019), fatty and sugary foods (Ruddock & Hardman, Reference Ruddock and Hardman2017), and intoxicants (Edelstein et al., Reference Edelstein, Wacht, Grinstein-Cohen, Reznik, Pruginin and Isralowitz2020; El Khoury, Noufi, Ahmad, Akl, & El Hayek, Reference El Khoury, Noufi, Ahmad, Akl and El Hayek2019) can be addictive – and people likely associate addiction with loss of self-control (see Vonasch et al., Reference Vonasch, Clark, Lau, Vohs and Baumeister2017). In vignette studies, we found that participants judged individuals increasing their indulgence in bodily pleasures over several months (e.g., pornography, alcohol, fatty and sugary foods) as altering their trait-self-control as a result of this lifestyle change (Fitouchi et al., Reference Fitouchi, André, Baumard and Nettle2022). Surveying religious attitudes toward pleasure, Glucklich (Reference Glucklich2020, pp. 13–27) concludes that the addictive character of food, sex, alcohol, or gambling, is a major concern across world religions. Reviewing attitudes toward sex in European history, Dabhoiwala (Reference Dabhoiwala2012) highlights that “It was a Christian commonplace that anyone who succumbed to this impure appetite [lust], even just once, risked developing a fatal addiction to it” (p. 33). In Hinduism, similarly, “Ancient Indian texts often call the four major addictions that kings were vulnerable to ‘the vices of lust,’ sometimes naming them after the activities themselves – gambling, drinking, fornicating, hunting” (Doniger, Reference Doniger2014, p. 365). Table 1 summarizes selected cases of such folk-psychological beliefs in various cultural contexts.

Table 1. Examples of folk-psychological beliefs about modifiers of trait-self-control

If people perceive that cooperation requires self-control (sect. 3.1.3), and that overindulgence in bodily pleasures reduces self-control, they may moralize bodily pleasures as indirectly facilitating uncooperative behaviors. For example, if indulgence in sexual pleasure in victimless situations (e.g., masturbation, frequent sex within marriage), is perceived as making people addict to sex, it becomes responsible for impeding the control of sexual urges in cooperative situations as well, where these impulses are socially harmful (e.g., when resisting them is necessary to avoid adultery). If victimless gluttony is perceived as making people addict to food, it becomes responsible for fueling uncontrollable urges which, in other situations, will prove socially harmful (e.g., when resisting food cravings is necessary to respect others' property). Repeated indulgence in bodily pleasures may be perceived, more generally, as decreasing self-control across domains, thus decreasing people's cooperativeness in general. This would be consistent with the lay theory we discuss next: That repeatedly practicing self-control would train self-control.

Self-control training, daily self-discipline, and ritual observance. Another recurrent lay theory seems to be that self-control can be trained by repeated practice – although the objective efficacy of such training is scientifically debated (Berkman, Reference Berkman, Vohs and Baumeister2016; Friese, Frankenbach, Job, & Loschelder, Reference Friese, Frankenbach, Job and Loschelder2017; Miles et al., Reference Miles, Sheeran, Baird, Macdonald, Webb and Harris2016). Field experiments on parents suggest a widespread belief that children's self-control can be improved, associated with self-control-training practices, such as giving children unhealthy snacks less often, or bringing them less frequently to fast-food restaurants (Mukhopadhyay & Yeung, Reference Mukhopadhyay and Yeung2010). In vignette studies, participants judged that sustained self-discipline over several months (e.g., exercising regularly, reducing indulgence in bodily pleasures) would likely improve a target's trait-self-control (Fitouchi et al., Reference Fitouchi, André, Baumard and Nettle2022). This is consistent with cross-culturally recurrent beliefs that investment in ascetic practices or effortful activities allow to “build character” and improve people's self-control (see Table 1).

If people perceive both that cooperation requires self-control (Righetti & Finkenauer, Reference Righetti and Finkenauer2011), and that regular self-discipline trains self-control, they may moralize effortful activities (e.g., waking up early, spiritual disciplines, needless hard work), as means to “build character” – that is, to improve the self-control required to honor prosocial obligations. This helps explaining another component of the puritanical constellation: The moralization of constant self-discipline, needless hard work, and unproductive effort, even when the latter are devoid of direct benefits to other people (Celniker et al., Reference Celniker, Gregory, Koo, Piff, Ditto and Shariff2023; Tierney et al., Reference Tierney, Hardy, Ebersole, Viganola, Clemente, Gordon and Uhlmann2021).

This also allows explaining the moralization of pious ritual observance. Indeed, psychologists have extensively argued that rituals of world religions, such as fasting, meditation, regular prayer, or effortful pilgrimages, appear specifically geared toward training self-control (Geyer & Baumeister, Reference Geyer, Baumeister, Paloutzian and Park2005; Koole, Meijer, & Remmers, Reference Koole, Meijer and Remmers2017; McCullough & Carter, Reference McCullough and Carter2013; McCullough & Willoughby, Reference McCullough and Willoughby2009; Tian et al., Reference Tian, Schroeder, Häubl, Risen, Norton and Gino2018; Wood, Reference Wood2017). These rituals require sustained restrictions of bodily desires (e.g., fasting), commitment to regular practice (e.g., praying five times a day, at fixed hours), cognitive effort (e.g., reading and memorizing the scriptures), and repeated inhibition of spontaneous tendencies (McCullough & Willoughby, Reference McCullough and Willoughby2009). We argue that these activities, as the rest of the puritanical constellation, are ascribed a moral disciplining function: Cultivating the self-control perceived necessary to honor prosocial obligations. This allows explaining why moralizations of diligent ritual observance cluster with other puritanical values (sect. 1.1) – so that “piety” is commonly listed, alongside temperance and restraint from bodily pleasures, among the core virtues of the “purity” morality (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt, Koleva, Motyl, Iyer, Wojcik and Ditto2013; Haidt, Reference Haidt2012; Haidt & Joseph, Reference Haidt and Joseph2007).

3.3. Puritanism and the moral mind

Our last assumptions concern the cognitive mechanisms of moral judgment. First, our account rests on a unitary theory of moral cognition, according to which moral judgments – including puritanical ones – are produced by a single, functionally unified cognitive system sensitive to cooperation (André et al., Reference André, Fitouchi, Debove and Baumard2022). In line with other unitary theories of moral cognition (Gray et al., Reference Gray, Waytz and Young2012, Reference Gray, Schein and Ward2014; Schein & Gray, Reference Schein and Gray2015, Reference Schein and Gray2018), we insist that the plurality of moral values at the cultural level does not imply the existence of a plurality of moral systems at the cognitive level. The same moral system can produce, based on the very same computational procedures, a wide variety of outputs, and thus culturally variable values, depending on the varying inputs that it receives (Aarøe & Petersen, Reference Aarøe and Petersen2014; Nettle & Saxe, Reference Nettle and Saxe2020, Reference Nettle and Saxe2021). In the case of puritanical norms, a domain-general system sensitive to harm (Gray et al., Reference Gray, Schein and Ward2014), or fairness (Baumard et al., Reference Baumard, André and Sperber2013), can moralize victimless behaviors, as long as it is fed by causal representations depicting those behaviors as indirectly leading to socially harmful outcomes.

Second, we assume that this moral system is triggered not only by intrinsic instances of uncooperative behaviors (e.g., violence, adultery, unfair sharing), but also by behaviors perceived as indirectly and probabilistically leading to social harm. This is consistent with experimental evidence that the triggering of moral judgment depends on the computation of a – potentially indirect – causal chain between a perpetrator's action and an undeserved cost imposed on another individual (Cushman, Reference Cushman2008; Guglielmo & Malle, Reference Guglielmo and Malle2017; Sloman, Fernbach, & Ewing, Reference Sloman, Fernbach, Ewing and Ross2009). Victimless excesses should be preemptively moralized when perceived to causally contribute, through their deleterious effects on self-control, to an increased prevalence of uncooperative behaviors. Restrained behaviors should be praised when perceived to positively contribute, through their preserving effects on self-control, to the improvement of people's cooperativeness.

3.4. The cultural evolution of puritanism as a behavioral technology

So far, we have focused on the psychological level of moral judgment. Yet puritanism also manifests in socially transmitted traits, subject to cultural elaboration. Carnal sins are not only judged in everyday life; they have been systematized in explicit religious classifications (e.g., the seven deadly sins; Hill, Reference Hill2011; Tentler, Reference Tentler2015). Ascetic rituals of fasting, meditation, or regular prayer have been crafted and institutionalized by doctrinal religions (Brown, Reference Brown2012; Tentler, Reference Tentler2015). Legal regulations of alcohol have been gradually elaborated and negotiated in cultural groups (Martin, Reference Martin2009; Matthee, Reference Matthee2014). Thus, the emergence of puritanical norms is also fruitfully conceived in cultural evolutionary terms. These puritanical cultural traits, we argue, have evolved as people, based on their folk-psychological theories of self-control, have attempted to facilitate self-control to ensure cooperative behavior.

Prominent cultural evolutionary theories argue that normative cultural traits, such as monogamous marriage (Henrich, Boyd, & Richerson, Reference Henrich, Boyd and Richerson2012), moralizing religions (Norenzayan et al., Reference Norenzayan, Shariff, Gervais, Willard, McNamara, Slingerland and Henrich2016), or large-scale cooperative institutions (Richerson et al., Reference Richerson, Baldini, Bell, Demps, Frost, Hillis and Zefferman2016), spread in human populations because they procure objective adaptive benefits by increasing cooperation. Although human enforcement mechanisms (e.g., reputation, punishment) can stabilize any norm (Aumann & Shapley, Reference Aumann, Shapley and Megiddo1994; Boyd & Richerson, Reference Boyd and Richerson1992), intergroup competition would favor cooperation-facilitating norms at the expense of other evolutionarily stable equilibria (Henrich & Muthukrishna, Reference Henrich and Muthukrishna2021). Thus, one possibility is that puritanical norms emerge through random variation, as one of the many stable equilibria that enforcement mechanisms can maintain, and are then favored by cultural group selection. In this perspective, puritanical norms should be objectively effective in increasing cooperation by facilitating self-control (see McCullough & Carter, Reference McCullough and Carter2013), and would be favored by impersonal selective pressures that are independent of people's understanding of the mechanisms these norms involve or the function they serve (see Henrich, Reference Henrich2017, Reference Henrich2020).