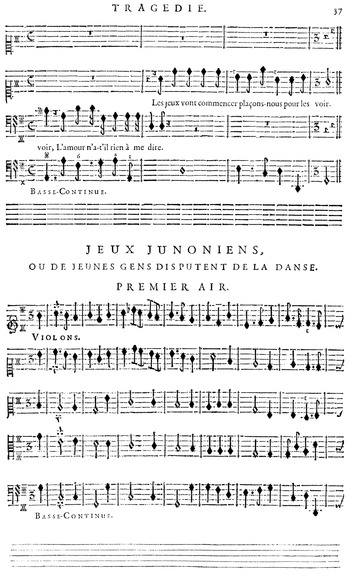

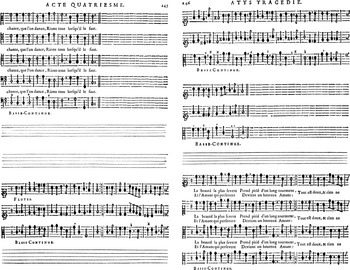

Just as the larger dramaturgy of divertissements is very carefully controlled, so too is their construction. Lully’s notational practices emphasize connectedness, as when the last measure of a recitative changes to the meter of the entrance music for the divertissement, which starts on beat 3 (Figure 2-1). This is not an operatic style that lends itself to interruption by applause; the sense of continuity is far too great. Yet even the most basic questions – such as who danced where – rarely have easy answers, and it is only after comparing every one of Lully’s divertissements to its fellows that I have come to identify his conventions. Because some of these have been misunderstood by both scholars and performers, I have felt compelled to lay out the evidence for my conclusions in some detail. This chapter explores the conventions Quinault and Lully developed that allowed for the integration of dance and song within dramatic structures that favor coherence and continuity.

Primary Sources

There is no single source to consult for establishing the mechanics of a divertissement. The two most basic are the librettos and scores associated with performances at the Opéra during Lully’s lifetime: a libretto was printed for each premiere, and, for every opera starting with Bellérophon (1679), a full score was printed by Christophe Ballard, under the supervision of Lully himself.Footnote 1 Isis was published in partbooks in the year of its premiere (1677), and for two earlier operas, Atys and Thésée, Ballard published full scores within two years of Lully’s death.Footnote 2 This means that, for ten out of Lully’s thirteen tragédies en musique, there are important contemporary sources for both the text and music. The eighteenth-century full scores for Cadmus et Hermione, Isis (both from 1719) and Psyché (1720) are less reliable than the earlier Ballard prints, as are the reduced scores published starting with Alceste in 1708 by Henri Baussen or the Ballard family.Footnote 3 But even the best of Ballard’s scores and librettos have ambiguities and errors; several problematic instances are discussed below.

To date, three operas have appeared in the new critical edition of Lully’s Œuvres complètes: Armide, Thésée, and Isis.Footnote 4 The two earliest tragédies, Cadmus et Hermione and Alceste, were published in the old edition of Lully’s works, as was the late opera Amadis. These three volumes are not without problems, but are nonetheless works of serious scholarship.Footnote 5 The piano-vocal scores published between 1876 and 1892 as part of the series Chefs d’œuvre classiques de l’opéra français cannot be considered reliable. Some extant copies of the Ballard prints were marked up for performance, although most of the annotations appear to date from the middle of the eighteenth century.Footnote 6 Numerous manuscripts of Lully’s operas survive; some are copies of the printed scores, others are commercial copies made by workshops such as the one established in Paris by Foucault; still others have unique pedigrees.Footnote 7 In addition, there are some performing parts for a few of Lully’s works preserved in Paris at the Bibliothèque de l’Opéra, almost all of them from the eighteenth century.Footnote 8 It is far beyond the scope of this book to take into account this mass of disparate and dispersed source material, even though some of it might contain useful information. I have thus relied on the original layer of Ballard’s full scores, librettos published during Lully’s lifetime, the librettos collected in the Recueil général des opéra,Footnote 9 and the available critical editions.

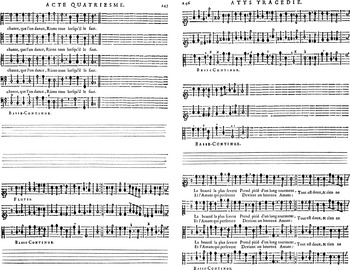

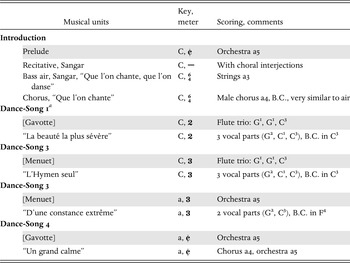

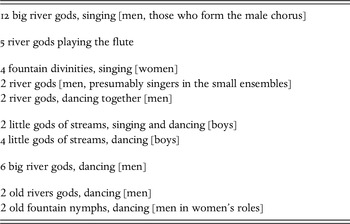

One subgroup of librettos are particularly useful: those that contain the names of the performers and thus combine the functions of libretto and program. These may reveal how the singing and dancing roles were distributed, how many performers of each there were, and whether there were any solo dancers. Such librettos generally list the performers in the prologue separately, the cast of the tragédie on pages just before the start of Act i, and the performers in the divertissements at the start of the relevant scene; see Figure 2-2, for Act iii of Atys. During Lully’s lifetime such librettos were printed only for court performances, but Lully did not mount all of his operas at court and not all such productions generated their own librettos.Footnote 10 There are no personnel records from the Académie Royale de Musique during Lully’s tenure and the extent to which the court and Palais-Royal productions had performers and staging practices in common can be only partially reconstructed. That said, the court librettos do represent performances done under Lully’s direction, and presumably represent practices he endorsed or initiated. When it comes to the dancers in particular divertissements, the numbers of performers are similar in the court librettos to those for revivals in Paris starting in 1699. This stability suggests that the differences between Paris and Saint-Germain performances during the 1670s as to how the dancers were deployed may not have been great.

In general, scores tend to have only rudimentary headings (Premier Air, Chœur de Nymphes), whereas librettos include more information about the characters appearing in a given scene. However, librettos focus on the sung texts and only rarely mention the dance pieces. It would be easy to infer from the Parisian libretto of Atys that Act v has no dancing at all, whereas the score includes three instrumental dances. But scores have their own limitations: they offer little guidance as to which characters do the dancing, and the sequence of events may sometimes be unclear.Footnote 11 Cases of ambiguity are signaled in the discussions that follow.

Because the librettos and scores do not provide sufficient information for reconstructing a divertissement, additional guidance must come from Lully’s contemporaries. The choreographies in Beauchamps-Feuillet notation that can be linked to the Paris Opéra would seem a likely place to start, but none originated during Lully’s lifetime, nor do they ever preserve more than one or two isolated dance pieces from an opera. There is, however, one fully choreographed stage work dating from 1688, the year after Lully’s death, the comic mascarade Le Mariage de la grosse Cathos; it conveys enormous amounts of information about how a work of musical theater was put together, notwithstanding its differences in genre and scale from Lully’s tragédies en musique. The mascarade, which was performed privately at Versailles in a large room, involves nine singers, eight dancers, and an on-stage, eight-member oboe band. Its composer, André Danican Phildor l’aîné, and choreographer, Jean Favier l’aîné, had both performed for years under Lully’s direction; Favier had almost certainly been a regular member of the Paris Opéra’s dance troupe since its inception. The dance notation (which uses Favier’s own system), preserves not only the ten choreographies that appear in the course of the approximately 45-minute work, but also shows some of the floor patterns traced by the singers and the on-stage instrumentalists.Footnote 12 This little work does not answer all the questions raised by a Lullian tragédie en musique, but the staging conventions it evinces prove valuable as a lens for examining Lully’s own practices. Another useful source is Marc-Antoine Charpentier’s autograph score for Circé, a machine play written by Thomas Corneille and Donneau de Visée in 1675.Footnote 13 Charpentier’s autograph includes annotations showing where the dancers do and do not dance; its practices in this regard are entirely consistent with those seen thirteen years later in Le Mariage de la grosse Cathos.

Some additional information about dance practices comes from seventeenth-century writings. However, during this period eyewitness accounts of performances are both rare and vague. And whereas dance theorists and aestheticians do offer important perspectives that are discussed in later chapters, they rarely deal with practicalities. Moreover, many writers from this period copy from each other without acknowledgement, a phenomenon that makes evaluating their remarks more difficult. The encyclopédistes delve into greater detail about useful musical and choreographic matters, but they were writing in the middle of the eighteenth century after more than one major aesthetic shift had occurred. The foundation for this chapter thus remains a close reading of the librettos and scores.

Interpreting the Didascalies

Generally speaking, the librettos supply more information about staging than do the scores. This comes in the form of didascalies; I have chosen to adopt the French word rather than the English “stage directions” because of its broader meanings. In Quinault’s librettos, the didascalies are of three types:

(1) identification of where the action takes place;

(2) the names of the characters who appear in a scene;

(Atys ii/2: “cybele, celenus, melisse, Troupe de pretresses de cybele”)

(3) an indication of what the characters are doing.

(Atys i/8: “Cybèle, carried by her flying chariot, enters her temple, all the Phrygians hasten to go there, and they repeat the last four lines that the goddess has pronounced.”)

Categories 2 and 3 are particularly useful, even if not as extensive as one would like. Convention dictated a change of scene number whenever characters entered or left the stage. Quinault’s didascalies note the presence of characters who remain silent as well as of the singers. In the second example above, three individuals and a group of priestesses are shown to be on stage, but as the scene develops only two of them – Cybèle and Célénus – sing. Melisse is given lines in the next scene, but the priestesses never open their mouths; in fact, they remain mute for the entire opera, even though they have quite a bit of stage time. Given that dancers are also silent characters, a system of enumeration that includes everyone who makes a physical appearance is extremely helpful.Footnote 14

On the surface the third category looks intended to tell the actors what to do. In practice, however, Quinault’s didascalies function quite differently. In this example the first two of the three clauses could be read as instructions for the performers, but the third is superfluous: the four lines of Cybèle’s text that the chorus repeats are written out twice in the libretto, once for her and again for them (see Figure 2-3). Perhaps the second two-thirds of the didascalie were intended to insist on the Phrygians’ urgency, to give a sense of the emotional climate, rather than to offer instructions for movement. In fact, category 3 didascalies often seem aimed at the armchair reader, as a means of enabling someone who is not in the theater to form a mental picture of the stage or to get a sense of a scene’s overall affect. At the conclusion of Proserpine, “The heavens open and Jupiter appears, accompanied by celestial divinities. Pluton and Proserpine come out of the Underworld, seated on a throne, and Cérès takes a place near her daughter.” This is not a set of staging instructions for a singer or for a director (a position that did not yet exist). Moreover, Lully’s operas were proprietary; there was no reason to write didascalies with future performers in mind.Footnote 15 It is worth remembering that librettos were often read for pleasure at home.

Another didascalie that seems aimed at the armchair reader comes from Roland iii/5: “Angélique leaves to find Roland, in order to keep him away from the port from where she plans to embark with Médor.” If this were a true stage direction, it could end after the first two words, but instead Quinault reveals Angélique’s intentions, which have no impact at all on the stage, since Angélique’s planned encounter with Roland does not figure inside the opera. Even when didascalies do appear to describe a set of events, the temporal frame may be difficult to pin down. In the following instance are the actions simultaneous or consecutive? “The nymphs and woodland gods hide, Alphée and Aréthuse descend to the Underworld, Cérès’s flying chariot stops, and the goddess gets out” (Proserpine iii/3). Didascalies often seem to offer a snapshot of an entire scene, one in which time is collapsed and dancing is implied only in the vaguest terms, such as the following from Atys ii/4: “The Zephyrs appear in an elevated, brilliant glory. The different peoples who have come to the fête for Cybèle go into the temple and try together to honor Atys, and they acknowledge him as the high priest for Cybèle.” This kind of didascalie seems akin to the engravings from the period that collapse several events into a single, impossible moment.Footnote 16

Sometimes Quinault’s didascalies do appear to describe the action, as in the dream sequence in Atys iii/4: “The nightmares approach Atys and threaten him with Cybèle’s vengeance if he scorns her love and does not love her faithfully.” This, however, paraphrases the sung texts rather than offering instructions for on-stage movement. Moreover, it applies to all the Songes funestes, without discriminating between dancers and singers. Such a didascalie makes a significant aesthetic statement about how group characters are conceived, but it does not help much with questions of staging.

Every now and then a didascalie offers a bit of information about the dancing, as in Thésée i/10: “A combat in the manner of the Ancients is formed,” or Roland i/6: “The chorus of Insulaires sings […] and the other Insulaires dance in the manner of their country.” These two have the virtue of giving a hint, however vague, about the movement style. More often, however, the didascalies allude to the emotion the scene is supposed to convey, without mentioning through what kinds of movements the emotion is to be expressed: “The fairies and the shades of the heroes show, through their dances, the joy they feel at Roland’s return to health” (Roland v/3); or “The followers of Hatred show that she is making ready with pleasure to triumph over Love” (Armide iii/4). A few appear to offer help as to where in a scene the dancing occurs (“The Arts, disguised as gallant shepherds […] are the first to start dancing” (Psyché v/4)), but matching such remarks with the score often proves a challenge.Footnote 17 Yet even with their limitations, didascalies offer a crucial tool for envisaging the dances within an opera.

The Mechanics of Lully’s Divertissements

The Characters

The “verisimilitude of the merveilleux” identified by Kintzler allowed for human and divine characters to mingle freely throughout the opera, and the structure of the divertissement promoted a free exchange between individuals – including the main characters – and groups. But as a practical matter, the functions of singing and dancing were supplied by different people, whether they represented gods or humans, individuals or collective characters. A division of labor is explicit throughout the librettos, where in divertissement after divertissement the lists of roles distinguish between those who sing and those who dance. Occasionally a semantic distinction is even made between a chœur (singers) and a troupe (dancers), even when the characters are members of the same group: “Chœur de Phrygiens chantants, Chœur de Phrygiennes chantantes, Troupe de Phyrigens dansants, Troupe de Phrygiennes dansantes” (Atys i/7). The librettos that provide the performers’ names are even more explicit: the 1677 libretto of Alceste identifies sixteen of the attacking soldiers in Act ii as singers and four of them as dancers, while among the defending combatants there are only six singers, but still four dancers.

Even if functionally distinct, such characters were conceptually unified, subsumed into a single group. A typical didascalie identifies the performers in Alceste v/6 as “a troupe of shepherds and shepherdesses, some of whom sing, the others of whom dance.” Furthermore, the collective characters are all engaged in the same enterprise: “The people of the kingdom of Damascus show, through their dances and their songs, their joy about the advantage that the princess’s beauty has won over Godefroy’s knights” (Armide i/3); or “the shepherds and silvans, dancing and singing, come to offer presents of fruit and flowers to the nymph Syrinx, and they attempt to persuade her not to go hunting, and to submit herself to Cupid’s laws” (Isis, iii/6). In this division of labor, one group supplies the text, the other the movement; the dancers serve, in a sense, as surrogates for the singers. Another way of conceptualizing this type of casting is to see every role as being assigned two sets of bodies, although the number of singers and dancers need not be equal for the principle to apply. The modes of discourse may be different, but the expressive goals are the same.

This amalgamation of singers and dancers into a single entity is also implicit in the writings of aestheticians, who locate its roots in the chorus of ancient Greek tragedy, which they understood to have been danced as well as sung:

It is permissible to mix ballets into musical representations, because the two are made for each other and this blend is both pleasing and natural – not at all freakish. Tragedies may also have ballet interludes, because such ballets are to the tragedy what the choruses of the Ancients were, where one sang and danced.Footnote 18

Barring a few infidelities made to verisimilitude, opera is almost a tragedy such as the Greeks had. For if we have introduced into our operas some things that they would have repudiated and that they certainly would not have wanted, in recompense we have retained their choruses, which our [spoken] French tragedies have rejected. By that means, I argue, opera makes up for some of its defects and has acquired a great advantage over tragedy.Footnote 19

One important distinction emerges not along functional lines, but on the basis of gender. Quinault and the librettists who followed him were scrupulous in distinguishing between male and female roles: in most cases a scene will have both Bergers and Bergères, Phrygiens and Phrygiennes. The one exception is with troupes of “peuples,” where it is understood that the populace includes both men and women. Quinault’s syntactical distinction was not pedantic; Lully often composed passages or even entire numbers for the male or female subgroups, be they singers or dancers. Some divertissements may involve characters of a single gender only, as when Proserpine sings with her nymphs in Act ii of the eponymous opera; demons, in Lully’s operatic world, are always male. The French language easily allows for this distinction, but sometimes a libretto may attribute different names to groups who nonetheless function together. There is, for instance, no such being as a male Amazon, so in Bellérophon i/5 the corresponding male roles are for Solymes, a warlike people from Lycia in Asia Minor whom the mythological Bellerophon is reputed to have conquered. (The distinction is one of role, not of the gender of the performer; the singing Amazons in Bellérophon were performed by six men and six women, and all of the dancers, both Amazons and Solymes, were men.Footnote 20) Shepherds might be paired with either shepherdesses or nymphs; in both cases all are treated as members of a single group. There are, however, some cases where there are genuinely distinct groups on stage at the same time, often set up in opposition to each other. Two groups react in song and dance to the tragic death of Atys; a group of female Corybantes (followers of the goddess Cybèle) expresses rage, while a mixed chorus of wood and water divinities expresses sorrow (Atys v/7). Such divisions of the chorus and dancers into distinguishable groups, often the followers of separate gods, are likelier to occur at one end or the other of the opera – either in concluding celebratory divertissements or in prologues.

Very occasionally a chorus and a group of dancers may have different roles. In Act i of Persée, Queen Cassiope attempts to appease the wrath of the goddess Junon by offering games in her honor. The chorus is identified as spectators, whereas the dancers are “young persons chosen for the games.” In Act ii of Atys, the dancing Zephyrs have no choral counterpart, although there are also Zephyrs on stage playing instruments. More often, particularly in celebratory divertissements, the dancers may be a special subset of the population represented by the choral singers. In the last act of Phaéton the chorus is made up of diverse people – Egyptians, Indians, and Ethiopians – whereas the dancers are Egyptian shepherds and shepherdesses.

Rarer still than divertissements where the chorus and dancers have different roles are those that have dancers, but no chorus at all. In Phaéton i/7, “Triton comes out of the sea accompanied by a troupe of followers, of whom one group plays instruments and the other group dances.” Here the chorus has been replaced by on-stage instrumentalists; the only singers in this scene, during which Proteus transforms himself into several different shapes, are the two soloists: Proteus himself and Triton. In Cadmus et Hermione ii/6, Amour, the only singer in the divertissement, animates a group of golden statues, who jump off their pedestals and dance. Yet even here dancing is in close contact with singing. The vocal forces may sometimes be reduced, but in no Lully opera does dancing ever occur without some kind of vocal framework.

The instrumentalists on stage in Act ii of Atys are not unique: eleven court librettos for seven different operas provide the names of the instrumentalists who appeared on stage, and the example of Phaéton shows that such practices were not confined to court performances.Footnote 21 In other operas their presence is implicit; the didascalie in Amadis i/4 does not mention the trumpets that the score calls for, but as the scene staged a combat, military instruments would be natural. By bringing instrumentalists on stage Quinault and Lully could signal to the audience that a shift had occurred from the world of “speech” to a realm in which music is the medium of discourse; the opening of the dream sequence in Atys iii/4 is marked by the arrival of dreams playing viols, flutes, and theorbos (see Figure 2-2). On-stage musicians, like the singers and dancers, were assigned roles and costumed appropriately; there is a costume design by Berain for a priestess playing the “flute” in Thésée.Footnote 22 If the functioning of the on-stage oboe band in Le Mariage de la grosse Cathos bears a relationship to Lully’s practices (and its composer, Philidor, was an on-stage oboist in many of Lully’s operas), then Lully’s musicians may well have participated in the overall choreography, and not just remained fixed in place.Footnote 23

Other moving bodies beside dancers and musicians – supernumeraries or acrobats – were sometimes called upon to provide special effects. In Alceste, at the end of Act i, personifications of the winds are conjured up by Thétis and Aeolus: first the Aquilons cause a storm, then the Zéphyrs calm it;Footnote 24 the cast list for Act iii calls for “followers of Pluton, singing, dancing, and flying.” At the end of Act iv in Atys, flying Zephyrs whisk Sangaride and Atys away from her father’s horrified courtiers.Footnote 25 Also in Atys v/3, Alecton, a silent character, “comes out of the Underworld, holding a torch in her hand, which she shakes over Atys’s head,” driving him temporarily mad. Such characters are rarely identified by name in the librettos. One exception was the famous acrobat Allard, who played the role of a flying phantom in Thésée at Saint-Germain-en-Laye in 1675 and 1677. Spectacular special effects such as these appear to have been carried out by non-dancing personnel with the help of stage machinery.Footnote 26

One carryover from the conceptualizing of singers and dancers as all members of the chorus is the terminology, still in use at the Paris Opéra today, of “coryphée.” In the ancient Greek theater, the coryphæus meant the individual in a chorus delegated to speak individually, and at the Opéra, since 1779 if not earlier, coryphée has designated a rank for dancers who sometimes step out of the corps de ballet to do a solo or perform in a small ensemble. Similarly, in a Lullian divertissement an individual may step out of the chorus or the dance troupe, but still share the collective identity. In the scene of mourning in Alceste one of the singing Femmes affligées leads the group in its rituals, but leadership may also be entrusted to a dancer: in the first act of Proserpine, one of the dancing Sicilians has a solo role as the Conducteur de la fête. This particular role is mentioned in the main body of the libretto, but more often solo roles for dancers are only discernible from the lists of performers included in court librettos. The 1676 court libretto for Atys, for example, identifies Beauchamps as a soloist among the eight other dancing Songes funestes (see Figure 2-2). Whether in such an instance the soloist functioned as a leader of the group is unclear, but should be considered a possibility.

Solo turns inside divertissements are not confined to anonymous characters; singers of secondary roles may participate. This is the case with Céphise and Straton, confidants of Alceste and Licomède, who each sing a dance-song in Act v of Alceste; in Act i of Armide it is Hidraot, Armide’s uncle, who leads the celebrations in her honor. However, some of the characters who have names are episodic, appearing only in one act, even though their role may be crucial. Pluton and Proserpine in Act iv of Alceste are two such, as are Le Sommeil, Morphée, Phobétor, and Phantase – the fantastic beings who populate Atys’s dreams. In this scene the dancing analogues of these four singers are the Songes agréables.

The roles protagonists play in divertissements may be either active or passive. (Excluded from consideration are the fêtes where a protagonist does nothing but watch.) The dream sequence in Atys iii/4 is of the passive variety: Atys falls asleep on stage and the audience sees and hears what passes through his mind. In Persée ii/8–10 the hero is armed in a solemn ceremony by a series of divinities, so that he will be prepared to battle Medusa. On the active side of the ledger are divertissements ranging from fêtes to battles. Atys and Sangaride lead the ceremonies that honor the arrival of the goddess Cybèle (Atys i/7). It is within a sumptuous celebration that Médor and Angélique give full expression to their love (Roland ii/5). Proserpine frolics with her nymphs; the hidden Pluton is so taken with her charms that he interrupts the festivities to kidnap her (Proserpine ii/8–9). In the following act (iii/8) her mother, Cérès, and her equally enraged followers set fire to the earth.

The converse of placing protagonists within divertissements is giving voice to group characters in other parts of an act. Alceste opens with a sequence of brief choral interjections that wish happiness to the newlyweds. The chorus is listed in the didascalie, so is presumably on stage, but in other instances the chorus is either invisible (Amadis v/4) or sings from off stage (Bellérophon iv/2–3) and no dancers function in conjunction with their voices. Such spots are dramatically effective, but they do not figure in this study.

Staging the Dancers and the Chorus

A system that assigns function based on a specific skill set solves a practical problem of finding high-quality performers in both domains. Lully’s dancers were highly trained professionals. If they had an additional skill, it was usually playing the violin; many, among them such luminaries as Pierre Beauchamps and Jean Favier, came from families of violinists. Only occasionally was a performer good enough at singing and dancing to be hired to do both. Marie-Louise Desmâtins made her debut in Persée (1682) as both a singer and dancer, and her name appears in librettos in both capacities until 1703; thereafter, until her death in 1708, she sang only.Footnote 27

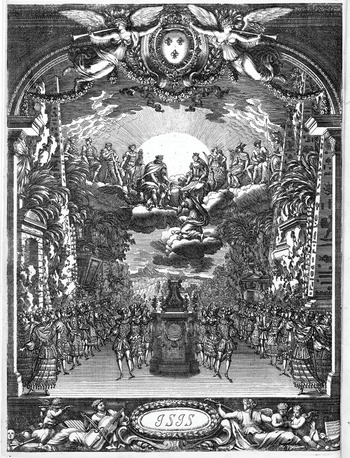

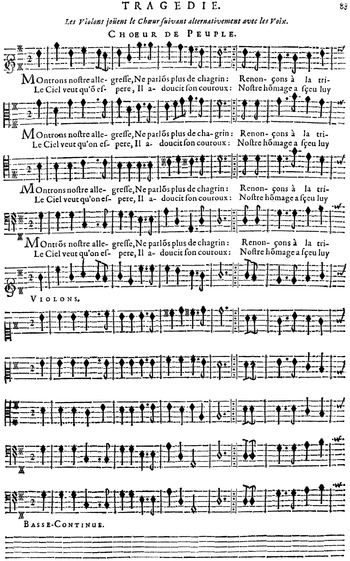

This division of labor impacts not only Lully’s musical constructions, but also the staging. If dancers are to provide actions on behalf of the chorus, they need space. Evidence from the eighteenth century suggests an arrangement of the stage with the chorus in two rows on its perimeter; as early as 1700 librettos listed the choristers according to which of two rows they stood in, and later in the century the choristers were identified as standing either on the queen’s side (stage right) or the king’s (stage left).Footnote 28 This arrangement was mocked by Fuzelier in a parody of Lully’s Persée done at the Théâtre Italien in 1722: “[the nymphs] take their places with the cyclopes along the two sides of the stage, like the chorus at the Opéra.”Footnote 29 In three Lully revivals between 1699 and 1705, chosen by way of example, the chorus constituted a substantial group: 35, 28, and 31 singers respectively.Footnote 30 According to mid-century writers such as Cahusac who complained about it, the chorus, once it had entered and taken up its positions, did not move, no matter what the text.Footnote 31 The chorus may not have been quite so immobile in Lully’s day as it was 75 years later: some of Quinault’s didascalies suggest movement, most notably one in Cadmus et Hermione iii/6, in which singing sacrificateurs prostrate themselves while other sacrificateurs dance; after the dance those who had been prostrated stand up and sing. But even in this scene the choristers might not have to do more than bow down and stand up in place; they still would need to be out of the way of the dancers, who perform between their moments of song. Figure 2-4 shows one such division of the stage: the concluding divertissement in Isis, with the chorus of Egyptians in two rows on the sides, the dancers surrounding the altar, and Jupiter and Junon, joined by other gods, welcoming Isis to the heavens.

The one contemporary document to show placement for the singers – the choreographic notation for Le Mariage de la grosse Cathos – does not have as rigid a use of space as the eighteenth-century evidence suggests, but it does show a concern with keeping the performers on the periphery until they become the focus of attention. Each of the different groups – singers, dancers, and instrumentalists – has a home position around the perimeter of the stage, from which individuals venture into the center when needed, only to retreat after their moment in the limelight.Footnote 32 In this modest work it is the oboists who occupy the sides of the stage, but in their use of space they seem somewhat analogous to the chorus in an opera.

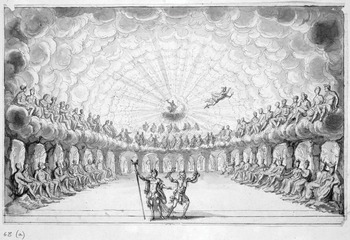

A relatively static approach to staging the chorus seems consistent with what can be gleaned from Lully’s librettos. In some scenes the chorus was even seated, as in the last act of Alceste: “the stage changes and represents a triumphal arch between two amphitheaters, where are seen a multitude of different peoples from Greece, assembled to welcome Alcide who has returned triumphant from the Underworld.” This strategic positioning leaves the center of the stage open. The libretto for Bellérophon, which has a similarly grandiose finale, describes the space as “the courtyard of a palace which appears elevated in the Glory. It is approached by two large steps […] which are enclosed by two large architectural structures of extraordinary height. The two steps and the surrounding galleries are filled with the people of Lycia.” The chorus of twelve Hours that sang in the Sun’s palace in Act iv of Phaéton was seated behind a cloud-enclosed balustrade in the 1721 revival, if not before.Footnote 33 The stage might have looked something like the one seen in Figure 2-5; in grandiose scenes such as these, the visual impression might have been increased by figures painted on the scenery, as Tessin reported in 1687.Footnote 34

It has been claimed that in French baroque opera the chorus generally remained on stage during the course of an entire act, but this assertion cannot be supported.Footnote 35 Lully’s librettists were scrupulous about listing the characters in every scene, to the point of mentioning characters who are present but do not sing. In the librettos the chorus and the dancers are generally shown to arrive together at the start of a divertissement, and Lully often composed music for their entrance. Moreover, their arrival is often preceded by some kind of invitation or anticipation. Roland hears shepherds arriving before he sees them (“J’entends un bruit de musique champêtre” (Roland iv/2)) and Atys, at the opening of the opera, repeatedly invites the Phyrigians to come honor Cybèle, before they finally arrive in Scene 7; he even offers a progress report in Scene 5. Prompt notes for mid-eighteenth-century performances of French operas call for entrances and exits of the chorus in expected places.Footnote 36 A case could be made that when the chorus appears without the dancers early in the act and then sings again a few scenes later, as in the last act of Alceste, it might have remained visible the entire time.Footnote 37 But acts constructed in this manner are considerably less frequent than ones where the libretto identifies the divertissement, which is usually well into the act, as the place where the chorus appears for the first time. It makes much more sense to conclude that the chorus, involving both dancers and singers, enters and leaves where the libretto says it does.

Once the two groups were on stage, how did they interact? At first glance the answer might seem straightforward: vocal pieces would be sung and instrumental pieces danced. But this begs the question of what vocal pieces that use dance rhythms might imply about movement on stage. Straton’s air in the last act of Alceste (“A quoi bon”) shares key, meter, gavotte rhythms, and overall affect with the dance that precedes it; the musical connections are so strong that the audience perceives this pair of pieces as a single unit. Would both have been danced? The available evidence suggests that the conventions were different for choruses than they were for solo songs or small ensembles. Whereas choruses could sometimes, within specific parameters, be danced, songs by soloists, no matter how danceable in affect, were not – at least not in Lully’s day. The next sections explore the separate conventions in turn.

Dance Inside of Choruses

Lully’s choruses come in many musical guises. But when it comes to how the singers and dancers behave relative to each other, the choruses reduce to four types: ones that have intermittent dancing; ones danced throughout; ones that involve some kind of movement other than dancing; and ones that have no dancing at all. It is not always a simple matter to identify the category to which a chorus may belong. However, models from Lully’s contemporaries provide enough data to offer a point of entry into the practices of the day.

Many of Lully’s choruses are celebratory and these often call attention to their own musicality: “Chantons tous, en ce jour, la gloire de l’amour,” sings the chorus at the conclusion of Amadis. The texts not infrequently also invite dancing: “Que l’on chante, que l’on danse,” sing Sangar and the chorus in Atys iv/5. Just this kind of text is found in Thomas Corneille’s machine play Circé, which was first performed by Molière’s troupe in 1675:

Chœur des Divinités des Forets:

Les plaisirs sont de tous les âges / Les plaisirs sont de toutes les saisons. / Pour les rendre permis on sait que les plus sages / Ont souvent trouvé des raisons. / Rions, chantons, / Folâtrons, sautons. / Les plaisirs sont de tous les âges / Les plaisirs sont de toutes les saisons.

(Chorus of woodland gods: The pleasures are always in season. Wise men have often found reasons for justifying them. Let’s laugh and sing and have fun and jump around. The pleasures are always in season.)

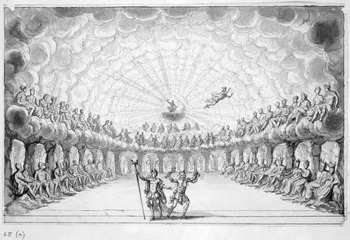

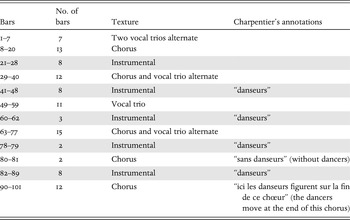

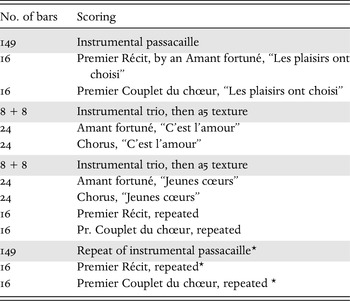

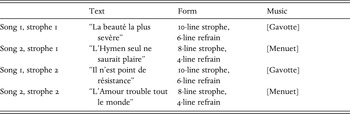

Charpentier’s music survives in his own hand; his annotations show not only that dancers were involved, but where.Footnote 38 This particular piece has three different textures: vocal trio, chorus, and four-part instrumental ensemble. The dancers’ participation is a function of the texture, as Table 2-1 shows. (Here and in subsequent tables, the instrumental sections are shaded.)

Table 2-1: Charpentier, Circé: chorus “Les plaisirs sont de tous les âges”.

| Bars | No. of bars | Texture | Charpentier’s annotations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1–7 | 7 | Two vocal trios alternate | |

| 8–20 | 13 | Chorus | |

| 21–28 | 8 | Instrumental | |

| 29–40 | 12 | Chorus and vocal trio alternate | |

| 41–48 | 8 | Instrumental | “danseurs” |

| 49–59 | 11 | Vocal trio | |

| 60–62 | 3 | Instrumental | “danseurs” |

| 63–77 | 15 | Chorus and vocal trio alternate | |

| 78–79 | 2 | Instrumental | “danseurs” |

| 80–81 | 2 | Chorus | “sans danseurs” (without dancers) |

| 82–89 | 8 | Instrumental | “danseurs” |

| 90–101 | 12 | Chorus | “ici les danseurs figurent sur la fin de ce chœur” (the dancers move at the end of this chorus) |

The dancers apparently remain still during the first instrumental phrase (unless Charpentier neglected to write an instruction), but thereafter they appear in every instrumental interlude, no matter how short. They do not, however, move when the chorus is singing, until the last twelve bars of the piece. The rapidity with which the dancers alternate between movement and stasis in response to the musical texture can be startling. Whereas most of the dance phrases are eight bars long, one lasts only three, and starting at m. 78 the dancers spring into action for a mere two bars before stopping out for another two.

The same pattern of alternation can be observed in Le Mariage de la grosse Cathos. In one of its choruses, whose four-line text celebrates the pleasures of life, Favier’s notation shows not only that this chorus was danced, but with what steps and to which phrases of the music. This simple piece consists of seven phrases, of which the four sung ones frame the three purely instrumental ones. The dancing occurs only during the instrumental sections, until the last choral refrain (see Table 2-2).Footnote 39

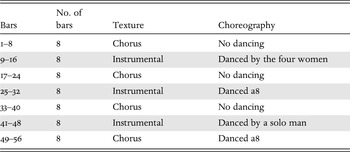

Table 2-2: Philidor, Le Mariage de la grosse Cathos: chorus “Passons toujours la vie”.

| Bars | No. of bars | Texture | Choreography |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1–8 | 8 | Chorus | No dancing |

| 9–16 | 8 | Instrumental | Danced by the four women |

| 17–24 | 8 | Chorus | No dancing |

| 25–32 | 8 | Instrumental | Danced a8 |

| 33–40 | 8 | Chorus | No dancing |

| 41–48 | 8 | Instrumental | Danced by a solo man |

| 49–56 | 8 | Chorus | Danced a8 |

Neither Philidor nor Charpentier wanted dancers to move while singing was going on – except during the concluding phrase. The general rule appears to be that only one thing should happen at a time, so that the two systems of discourse – textual and choreographic – do not compete for the audience’s attention. The music is the glue that holds the two systems together, and once the text has become familiar after multiple repetitions and the piece builds toward a conclusion, both singing and dancing are allowed to happen simultaneously. Thus the chorus ends with satisfaction for the eyes as well as the ears.

This pattern – identical in these two choruses, which between them frame Lully’s operatic career – has far-reaching implications. Many of Lully’s choruses are constructed along similar lines, with changes of texture from the vocal to the instrumental, sometimes even with further textural changes within the two basic divisions. Example 2-1 shows the end of a chorus from Armide iv/2, whose text invites participation by the dancers and whose musical construction allows for it. More importantly, the principle of alternation – of a single focus for the audience’s attention – turns out to have wide application, as the section below on dance-songs shows.

A second type of chorus is danced throughout – or almost so. The model, from Le Mariage de la grosse Cathos, again circumscribes where the dancing appears. This chorus repeats an astonishing announcement that has already been sung as a solo and a duet: “Allons, accourons tous / La grosse Cathos se marie.” (Come on, let’s all hasten, Fat Kate is getting married!”) Philidor’s chorus is sung throughout, with the brief text repeated three times. On the words “Allons, accourons tous” the dancers rush forward from either side of the stage, then freeze for two bars while they listen to the news. This pattern happens twice; on the third and last iteration of the text, the dancers move throughout the phrase and end by taking up positions that free the center of the stage for the approaching solo singers.Footnote 40 Would the dancers have moved throughout the entire chorus if its text had been different? With a sample of one only, we cannot know. But the impulse to end this chorus with movement as well as song seems to be one shared with the earlier choreographed chorus, as it serves to round out the number visually as well as aurally. This model suggests that choruses in Lully operas with action words might also be susceptible to choreographic treatment, whether or not they contain purely instrumental passages.

The third type of chorus involves a violent and frightening event, such as the earthquake that destroys part of Cérès’s palace at the end of Act i of Proserpine, while the members of the chorus comment on what they are watching. The chorus may either be sung throughout or else may have instrumental interludes that provide a convenient place for the action to take place. In Alceste ii/3–4, a battle wages between the soldiers attacking the city of Scyros and those defending it. A march brings the attackers on stage and the battle takes place during this double chorus; there is no other music available. Its action may be traced in the texts: after the dancing attackers bring in battering rams, their comrades sing “Let each of us eagerly fight; let us break down the towers and ramparts.” The response of the defenders suggests that their group of dancers shot arrows down upon the attackers: “May the enemy shudder under the hail of our arrows and spears.” The chorus is punctuated by instrumental phrases that feature trumpets and drums, and the meter changes as the battle progresses. Whether the dancers gestured while dancing or simply mimed is impossible to know, but in all performances for which librettos with the performers’ names exist, dancers, not supernumeraries, supplied the movement.Footnote 41

The battle in Persée iv/5–7, on the other hand, relies upon special effects, as the hero, using Mercure’s winged sandals to fly through the air, defeats the sea monster and rescues Andromède. The commentary sung by the two rival groups of spectators – Andromède’s fearful countrymen on the one hand, the water deities rooting for the monster on the other – is continuous, so the action has to take place while the chorus is singing. In Bellérophon iv/7, the hero battles with the Chimera that is ravaging Ethiopia. In what must have been a spectacular piece of stagecraft, Bellérophon, mounted on Pegasus, swoops down three times from the heavens, succeeds in killing the Chimera on the third pass, flies around the stage three more times, then rises through the clouds. An off-stage chorus describes the action as it happens, urges the hero on, and applauds his ultimate victory; their words are punctuated by vigorous instrumental passages. Such choruses provide plenty of visual stimulation, but require no dancers.

The fourth – and perhaps most common – treatment for choruses is no dancing at all. Here again Le Mariage de la grosse Cathos provides a useful model: of its five choruses only two are choreographed; the three that lack dancing also lack instrumental interludes. Moreover, none of them has the kind of text that invites physical movement. In many instances, it would appear, choruses are to be heard, not watched. Any dancers on stage (which in most instances there would be) simply stand in place. The proportion observable in Philidor’s masacarade – slightly more than half of the choruses are not danced – seems in line with Lully’s practices. In view of later practices, when composers made a point of identifying a chorus that was intended to be danced by labeling it a “chœur dansé,”Footnote 42 it would appear that the default was for choruses not to be danced, unless the structural or textual criteria were met. Nonetheless, every chorus should be considered as a possible candidate for choreographic treatment, the evaluation being made on the basis of its structure, text, location within the divertissement, dramatic context, and musical surroundings.

The Choreographic Treatment of Dance-Songs

One of Lully’s most reproducible conventions inside divertissements, especially those framed as fêtes, is the dance-song – a vocal piece with the structure of a dance (binary or rondeau), clear phrasing, and set to texts with short poetic lines that are more metrically regular than those in recitative, even if not every line has the same number of syllables (see the example from Phaéton on p. 71). Dance-songs may be set as solos, duets, trios, or choruses.Footnote 43 Solo singers are generally anonymous members of the choral collective (e.g., a shepherd), but sometimes are named secondary characters. The text may be strophic – in which case there are never more than two strophes – or it may have a single strophe only. Dance-songs are the property of divertissements; they are not found in other parts of the opera. This is another point of difference between Lully’s practices and Venetian opera, where strophic structures were one of the main ways for defining arias.Footnote 44 For the French, strophic structures called attention to themselves as music and had to be used diegetically. These pieces are certainly danceable – but were they in fact danced?

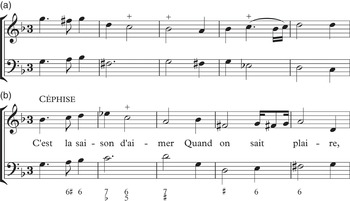

A dance-song never stands alone. Lully always pairs it with an instrumental dance piece that precedes or follows it (sometimes both) and that may carry a genre designation such as menuet or gavotte, but more often does not. In many instances the dance piece and the song are identical, except for the change in performing medium (see Figure 2-6). Alternatively, the song and the dance may be similar rather than identical, being related by key, meter, rhythmic patterns, phrase structures, and overall affect, as is the case with the two back-to-back dance-songs in the last act of Alceste. In each pair the text has only a single verse, and the dance comes first (see Example 2-2). There may even be no double bar between the two pieces, such that the notation alone encourages a continuous performance.

On musical grounds, there is no reason why dancing begun in the instrumental section could not continue on into the vocal one. Furthermore, some of the didascalies that Quinault wrote into his librettos might seem to suggest simultaneity of song and dance, including the ones for this very spot in Alceste: “Straton sings in the middle of the dancing herdsmen” and “Céphise sings in the middle of the shepherds and shepherdesses who dance” (“Straton chante au milieu des Pâtres dansants”; “Céphise chante au milieu des Bergers et des Bergères qui dansent”). Nonetheless, there are compelling reasons for concluding that the meaning of such didascalies is not transparent.Footnote 45 Rather, the general rule appears to be, yet again, that the dancing and singing occur in alternation. Moreover, Lully turns out to have had a blueprint for strophic dance-songs (see Table 2-5). The next several paragraphs lay out the evidence for these conclusions. The discussion of necessity becomes intertwined with notational conventions that Ballard used, as some of the ambiguity derives from space-saving shortcuts.

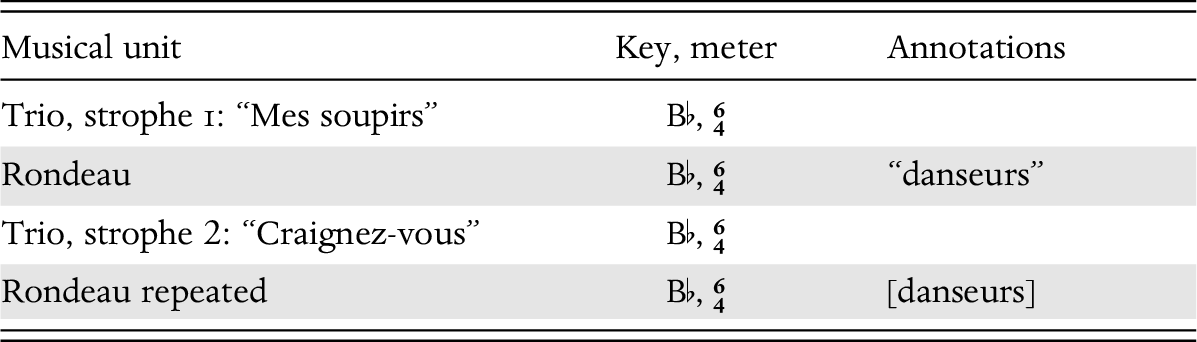

Table 2-3: Charpentier, Circé: outline of the dance-song “Mes soupirs.”

| Musical unit | Key, meter | Annotations |

|---|---|---|

| Trio, strophe 1: “Mes soupirs” | B♭, | |

| Rondeau | B♭, | “danseurs” |

| Trio, strophe 2: “Craignez-vous” | B♭, | |

| Rondeau repeated | B♭, | [danseurs] |

The aesthetic rationale implicit in the construction of choruses – one that shifts the focus back and forth between singing and dancing – would seem to apply even more strongly to solo songs, where the words are repeated much less than in choruses and therefore require more attention from the audience. In fact, not one of the solo songs or duets in Le Mariage de la grosse Cathos is choreographed, no matter how danceable the music. Charpentier’s Circé corroborates this pattern, in a strophic complex very similar in construction to many units found in Lully operas.Footnote 46

Charpentier made a point of the continuity from vocal trio to dance by omitting a double bar between them and by writing, “Go on without interruption to the following rondeau.” As he had in the chorus already cited (see p. 41), Charpentier annotated his score to show that he wanted the dancers to figure only during instrumental passages. Further annotations reveal that the dancers – or rather, acrobats (sauteurs) – run to get themselves into fixed positions, then move to another pose. The second strophe of the trio is said to follow the rondeau without interruption, after which “the rondeau is played again while the acrobats form three other figures, after which the play concludes with a chorus mixed with dances and dangerous leaps.”

The practice of alternation can be documented within Lully’s own operas, thanks primarily to explicit didascalies in the two librettos written by Thomas Corneille and Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle – Psyché and Bellérophon. Whereas Quinault was economical in his use of didascalies, Corneille and Fontenelle’s more generous approach helps clarify the order of events. In the prologue of Bellérophon three groups of characters are on stage: Apollon and the Muses; Pan with shepherds and shepherdesses; and Bacchus with Aegipans and Mænades. After a large chorus involving the followers of all three gods, the score presents three short binary pieces in a row, starting with a vocal minuet (Figure 2-7). This single page presents the entire piece: a didascalie above the music indicates that the instrumental and vocal music alternate, whereas a longer didascalie in the libretto insists that the shepherd sings after the first dance and that dance and song are interleaved. (“Les Bergers et les Bergères commencent ici une entrée, après laquelle un Berger chante les deux couplets suivants, qui sont entremêlés de danses.”) Table 2-4 outlines the order of events when the libretto and score are read together.Footnote 47

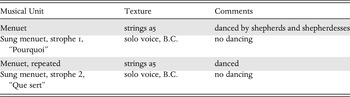

Table 2-4: Bellérophon, prologue: outline of dance-song “Pourquoi n’avoir pas le cœur tendre?”

| Musical Unit | Texture | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Menuet | strings a5 | danced by shepherds and shepherdesses |

| Sung menuet, strophe 1, “Pourquoi” | solo voice, B.C. | no dancing |

| Menuet, repeated | strings a5 | danced |

| Sung menuet, strophe 2, “Que sert” | solo voice, B.C. | no dancing |

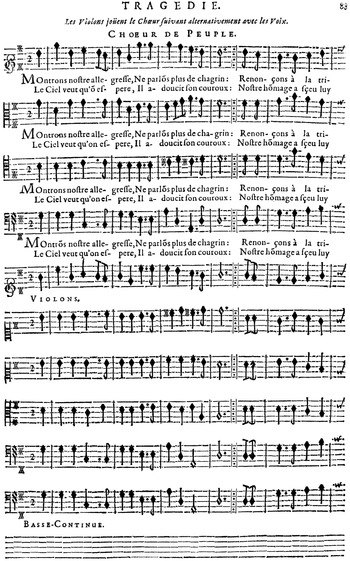

The identical structure appears in Bellérophon iii/5.Footnote 48 This complex divertissement, rich with didascalies, depicts a ceremonial sacrifice at the oracle of Apollon. It includes no fewer than three choral dance-songs, all exhibiting the same structure. In the second one the people dance around the fire and sing “Montrons notre allegresse.” Like many dance-songs it is binary and has short, clear phrases (Figure 2-8). Its strophic structure is discernible not only in the parallel construction of the two strophes, but is mentioned explicitly in the libretto, which makes a point of insisting that the didascalies belong in specific places relative to the sung texts. Two key words, “ici” and “ensuite,” anchor the sequence: “here the people dance around the fire, and then sing the first verse.” The libretto then writes out the first verse in full, followed by the instruction, “the people continue their dance, and [then] sing the second verse.” (“Then” is implicit in the “alternativement” written into the score.) Notwithstanding the alternation in performance, these didascalies further demonstrate the conceptual unity of the singing and dancing characters, who are treated as a single group (“le peuple”), even though their modes of communicating with the audience are not the same. The instructions are also valuable because Ballard did not print the dance separately from the chorus; the two are conflated into the choral version. It is obvious that the way to derive the instrumental version is simply to omit the voices; the orchestra part stands perfectly well on its own.

After a brief intervention by the Sacrificateur, there is another strophic chorus from which the alternating instrumental version must be derived. This one has a very different affect; the text begs Apollon for deliverance from the sorrows caused by the ravages of the monster. The music is in G minor, in (a presumably slow) triple meter, with an orchestral accompaniment that intersperses strings and trio passages for flutes. Yet notwithstanding the musical differences, the overall structure is the same. Thanks to the didascalies, we can be sure that its four-part structure consisted of dance – chorus strophe 1 – dance repeated – chorus strophe 2. The march that opens the divertissement also turns out to function in an identical way. It is a binary piece in gavotte rhythm and is followed by a chorus with the same rhythmic profile and the same structure. There is no verbal instruction in the score to repeat the march, but the libretto is clear : “here a second entrée is done, after which the people sing the second verse.” Not only is the march the only available instrumental piece, its close musical relationship to the chorus makes it the only piece that could possibly fulfill the function.

The principle of alternation seems to apply to the rest of this divertissement as well: every time action is required, such as when the bull is sacrificed or the Pythie emerges from her cave, instrumental music is supplied. The same principle applies to i/5 of this opera: “The Amazons and Solymes begin their dances here and then sing the following words, of which each verse is sung after a dance.” (Emphasis added.) This particular divertissement offers a slightly expanded variant on the pattern: a dance that is independent of the vocal music (“Premier Air”) opens the sequence, but thereafter comes a four-part choral dance-song, initiated by the dance piece (the “Second Air”).

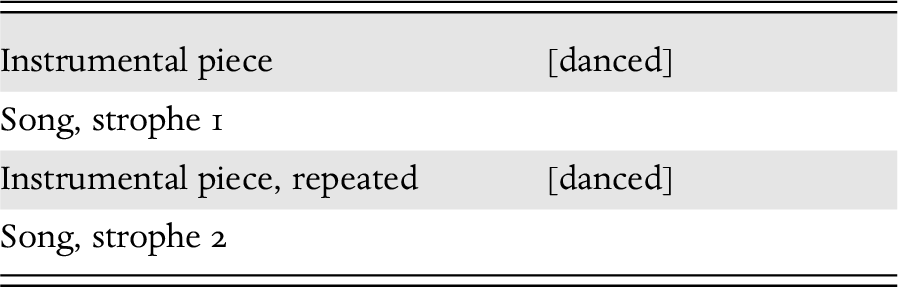

The sources for Bellérophon thus reveal two important principles: (1) the norm is for singing and dancing to alternate; and (2) dance-songs with a strophic construction adhere more often than not to the blueprint shown in Table 2-5. This structure applies whether the song is choral, solo, or for a small ensemble. Ballard’s notational practices often obscure the order of eventsFootnote 49 – perhaps because it was too obvious to need spelling out – but thanks to the more generous didascalies in the libretto for Bellérophon, the structure of the convention emerges.

Table 2-5: Lully’s dominant blueprint for strophic dance-songs.

| Instrumental piece | [danced] |

| Song, strophe 1 | |

| Instrumental piece, repeated | [danced] |

| Song, strophe 2 |

After studying the informative didascalies in Bellérophon, one returns to Quinault’s librettos with a different eye. Occasionally Quinault does make the same kind of distinction, as when in Thésée iv/7 the inhabitants of the enchanted island dance “to the tune of the shepherdess’s song,” which is played by rustic instruments. But the question remains whether or not didascalies such as the ones in the last act of Alceste, where Céphise sings “in the middle of” (au milieu de) shepherds and shepherdesses who dance, or the one from Isis iii/3, in which “one part of the nymphs dances during the time that the others sing” (“Une partie des Nymphes dansent dans le temps que les autres chantent”) can be read as calling for the simultaneity of song and dance. If one chooses to read such didascalies literally, one would be obliged to conclude that Lully staged dance-songs differently when Corneille was the librettist than when Quinault did the writing – that the dancing and singing are interleaved in Bellérophon and Psyché, whereas in Quinault’s operas, they are simultaneous. That explanation does not pass the test of Occam’s razor. Quinault’s didascalies cannot be read as if they had been written in the nineteenth or twentieth century. Rather, they rely on verbal formulas that give a global overview of several minutes of a scene, in which time is collapsed.

A passage from Menestrier supports a sequential interpretation of dancing “in the middle of” singing:

Just as musical performances are sometimes interrupted by ballet entrées, it is also possible to interrupt ballet entrées with songs. In the ballet entitled Le Triomphe de l’Amour, which was danced for the king and queen last winter, [the goddess] Diana sang in the middle of dances by her nymphs, and an Indian man and two Indian women sang in the middle of another entrée. A nymph among the followers of Youth sang in the middle of another entrée.Footnote 50

Menestrier’s examples are of one art “interrupting” the other; his “in the middle of” means “in between parts of.”Footnote 51 Quinault’s formulaic language makes much more sense interpreted in this vein, as a shorthand, rather than as a descriptor.Footnote 52 The practice of alternating song and dance is observable on other stages as well: at the Théâtre Italien, the fair theaters, and in ballets done at Jesuit colleges.Footnote 53 The practice seems to have been widely observed, not confined to the stage of the Académie Royale de Musique.

Yet even once we recognize alternation as a governing principle, the order of events may appear ambiguous. Although many Ballard scores do supply instructions (e.g., Roland i/6, 68: “On reprend l’air et la chanson encore une fois”), many strophic songs have none. In unmarked cases should we assume that, following the dance, the two strophes are sung one directly after the other? I think not. Among Lully’s dance-songs, the strophic construction outlined in Table 2-5 is by far the dominant model. The dance and the song may either be identical or closely connected; the strophes may have a refrain or lack one;Footnote 54 the form of each strophe may be either binary or rondeau; the song may be sung by an individual, an ensemble, or a chorus. But however those parameters may vary, the four-section unfolding of the piece, starting with the dance, is the most common construction.Footnote 55

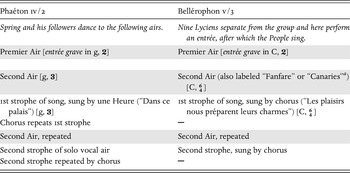

A tiny number of four-section structures reverse the order and put the vocal part first; in Thésée iii/7 a chorus of shades (“On nous tourmente / Sans cesse aux Enfers”) is followed by a dance (“Second Air”), the second verse of the chorus, and a repeat of the dance – all of them fully written out in the Ballard score. The basic dance-song structure may be expanded by including both a soloist and a chorus (see Table 2-6 for an example from Phaéton). Another type of expansion, although rare, consists of adding a third iteration of the dance after the second verse of the song.Footnote 56

| Phaéton iv/2 | Bellérophon v/3 |

|---|---|

| Spring and his followers dance to the following airs. | Nine Lyciens separate from the group and here perform an entrée, after which the People sing. |

| Premier Air [entrée grave in g, | Premier Air [entrée grave in C, |

| Second Air [g, | Second Air (also labeled “Fanfare” or “Canaries”a) [C, |

| 1st strophe of song, sung by une Heure (“Dans ce palais”) [g, | 1st strophe of song, sung by chorus (“Les plaisirs nous préparent leurs charmes”) [C, |

| Chorus repeats 1st strophe | ─ |

| Second Air, repeated | Second Air, repeated |

| Second strophe of solo vocal air | Second strophe, sung by chorus |

| Second strophe repeated by chorus | ─ |

a Although not so labeled in the Ballard score, this piece and the chorus that follow are called “canaries” in several musical sources (see LWV 57/69-70) and in a notated choreography (see Ch. 4, p. 112).

Not all of Lully’s dance-songs are strophic. When the song has only one verse, it is often embedded in the center of an ABA structure, with a dance to which it is closely related on both sides. Another formal option presents the dance and the related song only once each, in which case it is more common for the dance to go first, as with the back-to-back dance-songs in Act v of Alceste, sung by Straton and Céphise. When the order is reversed and the vocal piece is heard first, the context generally carries extreme emotion, as in Armide iii/4, when the followers of Hatred insist in rapid and forceful homorhythms that nothing causes so much suffering as Love (“Tu fais trop souffrir sous ta loi. / Non, tout l’Enfer n’a rien de si cruel que toi”). The dance that follows (“Second Air,” marked “Vite”) interposes jagged hemiolas into the rapid ![]() meter. According to the didascalie, “the followers of Hatred show that she is preparing with pleasure to conquer Love.” The cumulative threat of chorus and dance so horrifies Armide that she abruptly changes her mind and renounces Hatred’s help. In a similarly charged scene, Atys iii/5, the chorus of nightmares is followed by a vigorous dance in the same meter (

meter. According to the didascalie, “the followers of Hatred show that she is preparing with pleasure to conquer Love.” The cumulative threat of chorus and dance so horrifies Armide that she abruptly changes her mind and renounces Hatred’s help. In a similarly charged scene, Atys iii/5, the chorus of nightmares is followed by a vigorous dance in the same meter (![]() ); Atys wakes up terrified.

); Atys wakes up terrified.

A strophic dance-song, juxtaposed with a related dance piece, offers a clear structure for the alternation of song and dance. However, there may be some instances in which such units would seem to invite participation by dancers at the end of the second strophe. It is hard to imagine that the celebrations that conclude an opera such as Bellérophon, which ends with a strophic choral dance-song, would leave the dancers standing still during the final measures, no matter how the chorus is constructed (see the outline in Table 2-6). In this instance the sung canarie has a refrain, so a likely spot for the dancers to join the singers would be the B section of the second strophe, when the refrain is sung for the second time. This would respect the principle of not having dance compete with new text, yet would still allow the opera to end in spectacular fashion, with all the characters on stage taking part.

Structures in which an instrumental piece is related to a song or chorus in one of the ways discussed above account for approximately two-thirds of the instrumental dance pieces in Lully’s operas. This close correspondence between the vocal, text-bearing realm and the world of physical movement is one of the hallmarks of French opera, but the aesthetic principle of a single focus that governs how the two realms interact may seem counterintuitive to today’s opera spectators, who are used to seeing many activities happening on stage at once. Rosow has extended the principle of a single focus to argue that whereas Lully and Quinault generally separated dancing and singing in real time, within the realm of the opera, which operates according to different rules than does the outside world, the two happen, in a sense, simultaneously:

A corollary of this principle of single focus is its implication of continuous behavior that the audience neither sees nor hears. While we watch the dancing Ethiopians, the singing Ethiopians continue to celebrate, but we do not hear them; while we hear the singers, the dancing Ethiopians continue to celebrate, but we do not see them […] Lully and Quinault want us to understand these activities to occur simultaneously as we focus on them successively. The conventional code for presenting such a structure involved symmetrical patterning: an apparently static tableau.Footnote 57

Independent Instrumental Dances

Whereas most of Lully’s instrumental dance pieces are intimately connected to a vocal piece, approximately one third of them have no musical relationship to the rest of the divertissement other than key, and, perhaps, meter. One independent type is the marche, which often provides the entrance music in ceremonial contexts. Marches that involve military processions, as in the battle scenes in Act ii of Alceste and Act i of Thésée, are in rondeau form with trumpets and drums playing during the refrains. The triumph in honor of Bellérophon in i/5 receives the military musical treatment, even though those processing are not soldiers but the hero’s prisoners from a campaign conducted before the opera starts. Armide’s triumph in Act i, however, has no trumpets and drums, perhaps because those entering, the people of Damascus, are civilians, even if they are celebrating her military successes – or is it because she is a woman and only men merit trumpets? The fact that marches are not usually anchored to vocal pieces seems unsurprising,Footnote 58 and they are generally followed by something sung, often an announcement in recitative, setting the scene for what is to come.

Other ceremonial processions may be set to marches, such as the entrance of people offering gifts to the goddess Isis in Phaéton iii/4. The libretto specifies that “the young male and female Egyptians who carry the offerings approach the temple of Isis while dancing.”Footnote 59 A possible model for performing such a piece is offered by the single extant march choreography, the opening number in Le Mariage de la grosse Cathos. There the through-composed music is played twice, first as a processional for the entire cast, the second time as a dance for eight. During the procession everyone takes one step per measure, whereas the choreography assigns the dancers a varied step vocabulary.Footnote 60 Given the large number of people entering the stage in Phaéton iii/4 and the relatively short music available (a binary piece of 18 notated bars – or 36, if both repeats are made), the option of playing the entire piece twice so that the entrance can be made with due pomp is attractive. An extension of the amount of music also offers the possibility of highlighting the gift-giving by making the dancing subsequent to, rather than simultaneous with the procession.

One other category of instrumental dance does not have a vocal analogue – the entrée grave. This is a slow dance in duple meter characterized by dotted quarter-note/eighth-note patterns, rather like the opening portion of an overture. The adjective “grave” is found in the headings for choreographies (see Chapter 3, pp. 94–95); in scores such a piece is generally identified simply as an entrée or an air. Nor do scores often say to which group of dancers a piece may be assigned, but in choreographic sources entrées graves are always danced by men, and in the divertissements that include one there are always male characters – or nasty creatures that are coded male – available to dance it. One such instance is the first dance for the nightmares in Atys (Example 2-3).

In divertissements where they are used, entrées graves tend to be the first purely instrumental dance, perhaps following a chorus. They are often followed by another instrumental dance in a contrasting character, but one that is part of a dance-song complex. This is the case in Phaéton iv/2, which takes place in the palace of the Sun, where the next dance is in a light triple meter and tied both to a solo vocal air and to a chorus on the same text. Similarly, in the celebrations that end Bellérophon the entrée grave is followed by two canaries, the first instrumental, the second sung by the chorus. In both of these cases, the second unit adheres to Lully’s normal blueprint for dance-songs, with the one difference that the unit in Phaéton uses an expanded version, involving both a soloist and the chorus (see Table 2-6).Footnote 61

The dream sequence in Atys iii/4 is organized differently. After the Songes heureux have been dispatched by a bass Songe funeste, who warns Atys in recitative that if he refuses Cybèle’s love, she will take revenge, the dancing nightmares embody the warning in the entrée grave shown above in Example 2-3. Next a pair of related pieces – chorus and dance – reinforce the threat. (See Section iii in Table 2-11, p. 64.) Here, as in the other two operas, the entrée grave makes a strong statement on its own through music and movement. Yet Lully does not often present dance pieces in isolation, and in all three of these cases, the very next dance returns to the orbit of vocal music and a sung text. This phenomenon is not limited to cases that involve entrées graves. In Phaéton v/4 a bourrée is the musically independent piece, but it is immediately followed by a strophic dance-song.

It occasionally happens that Lully places two – or once even three – independent dances in a row,Footnote 62 but he nonetheless integrates them into a dramatic whole. In Act iv of Armide the Chevalier danois and Ubalde have come looking for Renaud, intending to rescue him from the sorceress’s clutches. Armide tries to distract them by conjuring up false images of their own sweethearts; the first such temptation, aimed at the Chevalier danois, constitutes the divertissement proper (iv/2). First, his beloved Lucinde, seconded by a chorus of rustic folk, tries to charm him (“Voici la charmante retraite”). Next come a gavotte and a canarie that have no musical connection either with each other or with the choruses on either side. The second chorus, however, follows the same pattern as the first (Lucinde’s words and music are repeated by her followers) and it quickly transforms into a repeat of “Voici la charmante retraite.” Thus even though the two dances are musically independent, they are enfolded within a structure that circles back on itself.

Chaconnes and Passacailles

Chaconnes and passacailles, the largest of all the dance types, have affinities with both the independent dances and the dance-songs, in that of the six such dances in Lully’s tragédies, two of them are purely instrumental (the chaconne in Phaéton ii/5 and the passacaille in Persée v/8), whereas the other four incorporate vocal sections (the chaconnes in Cadmus et Hermione i/4, Roland iii/6, and Amadis v/5, and the passacaille in Armide v/2). Of these the only one to end the opera is the enormous chaconne in Amadis; the oft-repeated claim that Lully’s tragédies end with chaconnes is not accurate.Footnote 63

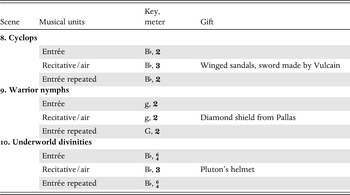

The passacaille from Armide illustrates how Lully interweaves vocal and instrumental sections into a gigantic construction (see Table 2-7). If all the repeats the Ballard score calls for are taken, the piece lasts approximately fifteen minutes and has 522 measures. The chaconnes from Amadis and Roland are longer still, each having over 800 bars. (It is not unusual for these long pieces to have internal repeats, although many are through-composed. When repeats are indicated by sign or by verbal instructions, how much music to repeat is sometimes ambiguous.)

Table 2-7: Outline of the passacaille in Armide v/2.

| No. of bars | Scoring |

|---|---|

| 149 | Instrumental passacaille |

| 16 | Premier Récit, by an Amant fortuné, “Les plaisirs ont choisi” |

| 16 | Premier Couplet du chœur, “Les plaisirs ont choisi” |

| 8 + 8 | Instrumental trio, then a5 texture |

| 24 | Amant fortuné, “C’est l’amour” |

| 24 | Chorus, “C’est l’amour” |

| 8 + 8 | Instrumental trio, then a5 texture |

| 24 | Amant fortuné, “Jeunes cœurs” |

| 24 | Chorus, “Jeunes cœurs” |

| 16 | Premier Récit, repeated |

| 16 | Pr. Couplet du chœur, repeated |

| 149 | Repeat of instrumental passacaille* |

| 16 | Premier Récit, repeated* |

| 16 | Premier Couplet du chœur, repeated * |

In her critical edition of Armide, Rosow chose to adhere to the sequence of the piece copied into the two instrumental parts remaining from the premiere, which do not repeat the last three sections (marked in the table with asterisks). Even in this shorter form, the passacaille has 341 measures.Footnote 64 In both versions the passacaille is marked by an alternation between instrumental and vocal sections, a construction that lends itself to alternating dancing and singing; presumably the last sixteen measures, sung by the chorus to a now thoroughly familiar text, would also have been danced.

Whereas the chaconne and passacaille are both structured as unfolding variations above either a ground bass or a repeating harmonic pattern, they differ from each other both in their music and in the dramatic uses to which they were put. The passacailles in French opera tend to be in a minor mode and to start on the downbeat; whereas chaconnes are usually in a major mode and tend to begin on the second beat of the bar. Passacailles have a slower tempo than chaconnesFootnote 65 and narrower uses; they are often found in association with women, not infrequently when seduction is involved. Chaconnes have broader dramatic uses (and sometimes an exotic flavor); a substantial subgroup of them is comic.Footnote 66 Because their great length and exceptional construction color any divertissement in which they appear, chaconnes and passacailles are discussed in several parts of this book.

Divertissement Architecture

Lully’s divertissements vary enormously in length and structural complexity, but the most common elements are the close connections between vocal and dance music and the use of repetition as a structural device. The principle of expansion via repetition, built into dance-songs, appears at larger organizational levels as well and even extends beyond the divertissement into other parts of the act.Footnote 67 The divertissements are also unified by key: most remain in the same key throughout, unless they occupy more than a single scene; excursions away are limited to the parallel major or minor, or, if the mode is minor, to the relative major. The examples that follow lay out a few of Lully’s varied structures.Footnote 68

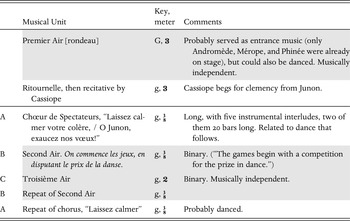

The organizing principle in Persée i/5 is a palindrome. When the opera opens Junon is angry with Cassiope, queen of Ethiopia, because she dared compare herself to the goddess. Junon has sent a monster, Méduse, to ravage the land. In an attempt to appease Junon, Cassiope leads a set of religious games, whose centerpiece is a dance contest (Table 2-8).Footnote 69 The jeux junoniens fail to calm Junon’s wrath and the news that Méduse is approaching sends everyone fleeing.

Table 2-8: Persée i/5: Cassiope, Andromède, Mérope, Phinée, followers of Cassiope carrying the prizes, young people chosen for the contest, chorus of spectators.

Games in honor of Junon, where young people compete in dancing.

| Musical Unit | Key, meter | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Premier Air [rondeau] | G, | Probably served as entrance music (only Andromède, Mérope, and Phinée were already on stage), but could also be danced. Musically independent. | |

| Ritournelle, then recitative by Cassiope | g, | Cassiope begs for clemency from Junon. | |

| A | Chœur de Spectateurs, “Laissez calmer votre colère, / O Junon, exaucez nos vœux!” | g, | Long, with five instrumental interludes, two of them 20 bars long. Related to dance that follows. |

| B | Second Air. On commence les jeux, en disputant le prix de la danse. | g, | Binary. (“The games begin with a competition for the prize in dance.”) |

| C | Troisième Air | g, | Binary. Musically independent. |

| B | Repeat of Second Air | g, | |

| A | Repeat of chorus, “Laissez calmer” | g, | Probably danced. |

The “Premier Air” fulfills the function of the marches found in so many ceremonial scenes, and, like them, is musically independent. It may well have been danced, especially given that some of the people entering the stage have been designated to participate in the dance contest. Cassiope probably enters last, as she has her own ritournelle before she addresses Junon; she explains that she has assembled young couples about to be married to demonstrate their skill in dance, and that she herself acknowledges her guilt and wishes to make amends. The chorus that follows, entreating Junon to heed the country’s pleas, represents the first of the five pieces in the palindrome. It is followed by three instrumental pieces: a dance in ![]() that is related to the chorus; a musically independent piece that may be a bourrée; and a repeat of the dance in

that is related to the chorus; a musically independent piece that may be a bourrée; and a repeat of the dance in ![]() . This central sequence, where the dance contest must have taken place, is rounded off by a repeat of the chorus. The connection made via the music between the dancers and the chorus of spectators, who beg Junon for mercy, reminds us that the dance contest is a serious matter. If the chorus did not involve dancing in its first iteration, it must surely have done so the second time, as both its position at the end of the divertissement and its construction invite dance: of its 113 measures, 58 are choral and 55 instrumental, in a lopsided alternating pattern that becomes more instrumental as the piece progresses (Table 2-9).

. This central sequence, where the dance contest must have taken place, is rounded off by a repeat of the chorus. The connection made via the music between the dancers and the chorus of spectators, who beg Junon for mercy, reminds us that the dance contest is a serious matter. If the chorus did not involve dancing in its first iteration, it must surely have done so the second time, as both its position at the end of the divertissement and its construction invite dance: of its 113 measures, 58 are choral and 55 instrumental, in a lopsided alternating pattern that becomes more instrumental as the piece progresses (Table 2-9).

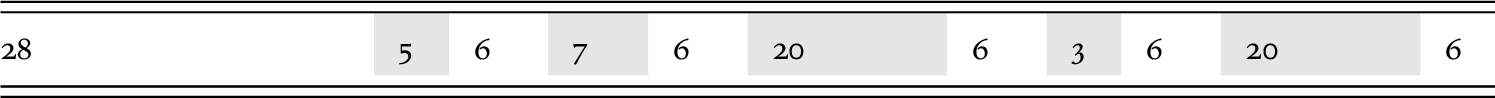

Table 2-9: Persée i/5: chorus “Laissez calmer votre colère”.

White = choral; shaded = instrumental

| 28 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 20 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 20 | 6 |