1 - A Portrait of a Young Woman as the Citizen-Soldier

from Part One - Before the Front, 1930s

Summary

Introduction: “My Fascist, as a Result, Remained Alive. And That Was Very Upsetting”

Late in the afternoon of February 26, 1939, Evgeniia Rudneva, a nineteen-year-old student in the Moscow State University mechanics and mathematics department, returned home in a “grief-stricken” (priskorbnyi) mood. Her machine-gun practice at the Kuskovo shooting range near Moscow had been nothing to be proud of. “I had to shoot with the hand machine gun,” Rudneva wrote in her diary. “I had to hold it in my hand and, of course, not one of twenty-five bullets hit the target. My fascist, as a result, remained alive. And that was very upsetting.” In response to her failure, Rudneva made a resolution: to learn to use the legendary heavy machine gun of the Civil War – the Maxim – and to “by all means, pass all the norms” for the Maxim badge. Six months later, Rudneva reported back to her diary that she had become master-sergeant of the machine-gun training group of her mechanics and mathematics department.

Like the majority of her contemporaries who participated in paramilitary training on the eve of World War II, Rudneva strove for mastery of the machine gun without entertaining a thought of turning the military into her life calling. Through her determined military practice, Rudneva claimed a different identity to legitimate her participation in combat: that of the citizen-soldier. She trained diligently, preparing herself to defend her Soviet country, according to her diary, when “the [war] hour comes.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

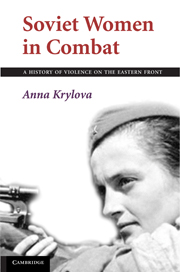

- Soviet Women in CombatA History of Violence on the Eastern Front, pp. 35 - 84Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2010