Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Terms and Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 The Filed Story of Niederungen

- 2 Contact Stories: The Author and the Officer

- 3 Conspiratorial Stories: The Securitate Sources MAYER, SORIN, and EVA

- 4 Captured Stories: Remote Audio Surveillance

- 5 Migrating Stories

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Appendix I Müller’s Surveillance Timeline (1974–93)

- Appendix II Author’s Accreditation by CNSAS

- Index

Introduction

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 June 2023

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Terms and Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 The Filed Story of Niederungen

- 2 Contact Stories: The Author and the Officer

- 3 Conspiratorial Stories: The Securitate Sources MAYER, SORIN, and EVA

- 4 Captured Stories: Remote Audio Surveillance

- 5 Migrating Stories

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Appendix I Müller’s Surveillance Timeline (1974–93)

- Appendix II Author’s Accreditation by CNSAS

- Index

Summary

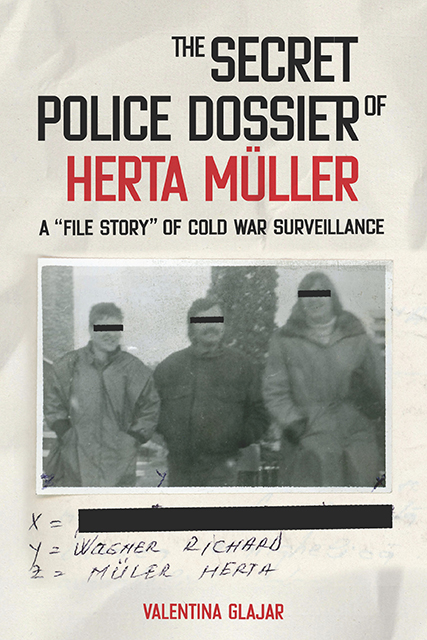

Herta Müller should share her Nobel with the Securitate.” This comment, made by the former secret police officer Radu Tinu, was in reaction to the news that Müller (b. 1953), a German writer originally from the Romanian village of Nitzkydorf, had just won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2009. Communist Romania's infamous secret police was indeed a protagonist in her work, though an undesired and dreaded one. Most of Müller's writings, whether fictional or essayistic, are deeply and explicitly anchored in Ceauşescu's Romania and its pernicious system of secret surveillance. In “Ode to Herta Müller,” the Romanian writer Mircea Cărtărescu lauds her Kafkaesque writings as “the product of an intense obsession, a unique, paranoid terror of being followed, held in suspicion, [and] persecuted.” Müller's Securitate file, discovered in 2009, does indeed trace and expose her surveillance by the secret police even after she emigrated to West Germany in 1987. The author herself reacted to reading her file in the file-based autobiographical text “Die Securitate ist noch im Dienst” (Securitate in All but Name) in 2009. In this work, Müller primarily addressed the gaps in her file; her text raises, then, the question about what information her file does, in fact, comprise.

Opening the secret police files at the end of the Cold War held out the promise of democracy and evidence of the former regimes’ repressive actions. Access to these files by ordinary citizens is “a strictly Eastern European method of reckoning with the past,” the political scientist Lavinia Stan claims in Transitional Justice in Post-Communist Romania. Yet few former Eastern bloc countries could keep pace with the government of reunited Germany, which declassified files of the East German secret police in 1992. Romania was no exception to this delay and its case exemplifies the many obstacles other former communist countries faced during the transition period, as most of the secret services remained in place even after the fall of the communist regimes. They may have been renamed, but none of the countries could produce brand new secret agencies overnight, and the existing ones were undoubtedly reluctant to come clean about their recent past. In post-1989 Romania, Stan argues, the new political leaders used (and misused) the files to discredit opposition leaders, while former secret agents realized that the information in these files could become “an efficient secret weapon, allowing them to become the new entrepreneurial elite.”

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Secret Police Dossier of Herta MüllerA 'File Story' of Cold War Surveillance, pp. 1 - 20Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2023