Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction

- 1 Isabella d’Este's Sartorial Politics

- 2 Dressing the Queen at the French Renaissance Court: Sartorial Politics

- 3 Dressing the Bride: Weddings and Fashion Practices at German Princely Courts in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries

- 4 Lustrous Virtue: Eleanor of Austria's Jewels and Gems as Composite Cultural Identity and Affective Maternal Agency

- 5 Queen Elizabeth: Studded with Costly Jewels

- 6 A ‘Cipher of A and C set on the one Syde with diamonds’: Anna of Denmark's Jewellery and the Politics of Dynastic Display

- 7 ‘She bears a duke's revenues on her back’: Fashioning Shakespeare's Women at Court

- 8 How to Dress a Female King: Manifestations of Gender and Power in the Wardrobe of Christina of Sweden

- 9 Clothes Make the Queen: Mariana of Austria's Style of Dress, from Archduchess to Queen Consort (1634–1665)

- 10 ‘The best of Queens, the most obedient wife’: Fashioning a Place for Catherine of Braganza as Consort to Charles II

- 11 Chintz, China, and Chocolate: The Politics of Fashion at Charles II's Court

- 12 Henrietta Maria and the Politics of Widows’ Dress at the Stuart Court

- Works Cited

- Index

7 - ‘She bears a duke's revenues on her back’: Fashioning Shakespeare's Women at Court

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 November 2020

- Frontmatter

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction

- 1 Isabella d’Este's Sartorial Politics

- 2 Dressing the Queen at the French Renaissance Court: Sartorial Politics

- 3 Dressing the Bride: Weddings and Fashion Practices at German Princely Courts in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries

- 4 Lustrous Virtue: Eleanor of Austria's Jewels and Gems as Composite Cultural Identity and Affective Maternal Agency

- 5 Queen Elizabeth: Studded with Costly Jewels

- 6 A ‘Cipher of A and C set on the one Syde with diamonds’: Anna of Denmark's Jewellery and the Politics of Dynastic Display

- 7 ‘She bears a duke's revenues on her back’: Fashioning Shakespeare's Women at Court

- 8 How to Dress a Female King: Manifestations of Gender and Power in the Wardrobe of Christina of Sweden

- 9 Clothes Make the Queen: Mariana of Austria's Style of Dress, from Archduchess to Queen Consort (1634–1665)

- 10 ‘The best of Queens, the most obedient wife’: Fashioning a Place for Catherine of Braganza as Consort to Charles II

- 11 Chintz, China, and Chocolate: The Politics of Fashion at Charles II's Court

- 12 Henrietta Maria and the Politics of Widows’ Dress at the Stuart Court

- Works Cited

- Index

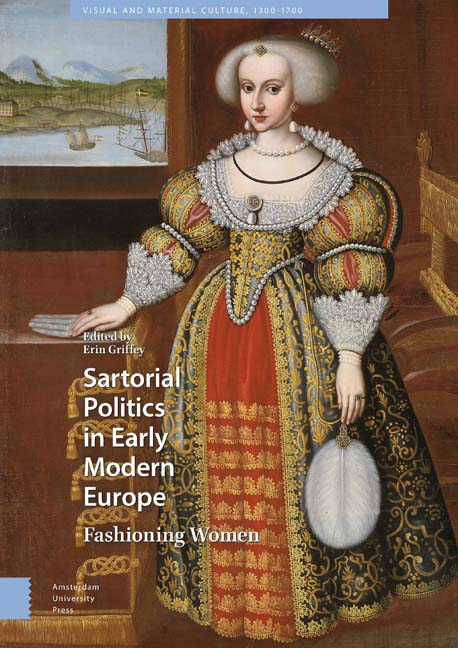

Summary

Abstract

When Shakespeare first staged his history plays and presented the great kings, queens, lords, and ladies from England's past, he did so using actors who were all commoners and exclusively male. To present these performers as England's historical elite, Shakespeare skilfully employed theatrical apparel to visually and materially construct his characters’ gender and social prominence onstage. This essay pieces together historical and textual evidence to establish what was originally worn in Shakespeare’s history plays and how it was understood by the English audience that attended the theatre. Such a study reveals that Shakespeare deftly engaged the visual semiotics of the time to establish and manipulate meaning onstage through the donning, doffing, and changing of silks, swords, crowns, and coronets.

Key words: Shakespeare; costume; crown; femininity; Henslowe; anti-theatrical

When Shakespeare rendered England's highly fraught political history into drama on the late sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century stage, he featured and manipulated theatrical apparel to fashion – literally ‒ gender and power in performance. The actors who performed in the early modern English playhouses were all male, and they were all commoners. Although no law prohibited women in England from performing before 1660, it was the accepted and expected norm that only men and boys would act on the professional stages. Some of these actors became wealthy enough to consider themselves gentlemen and a few even became squires (the great tragedian Edward Alleyn became Squire of the Bears), but none ever achieved a title or a place among England's nobility. And yet, these male commoners regularly played female aristocratic characters and assumed the roles of ladies, duchesses, and queens. One of the primary ways that they assumed these identities in performance was through the costumes they wore onstage. Considering the importance of costume as a marker of elite identity extends the function of clothing, fabrics, and jewellery from simple coverings to embodiments of gender and rank which, when worn, carried with them assumptions about power and privilege that were immediately recognisable to the early modern English public. While this essay focusses on dress within the performance of Shakespeare's plays on the early modern stage, its wider relevance to the essays of this volume is to reveal costume as a tool of performance offstage as well as on.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Sartorial Politics in Early Modern EuropeFashioning Women, pp. 161 - 182Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2019