Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Introduction: Beginnings in South Africa

- Chapter 1 Ambiguous Visibility: Muslims and the making of visuality

- Chapter 2 “Kitchen Language”: Muslims and the culture of food

- Chapter 3 “The Sea Inside Us”: Parallel journeys in the African oceans

- Chapter 4 “Sexual Geographies of the Cape”: Slavery, race and sexual violence

- Chapter 5 Regarding Muslims: Pagad, masked men and veiled women

- Chapter 6 “The Trees Sway North-North-East”: Post-apartheid visions of Islam

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

- Plate section

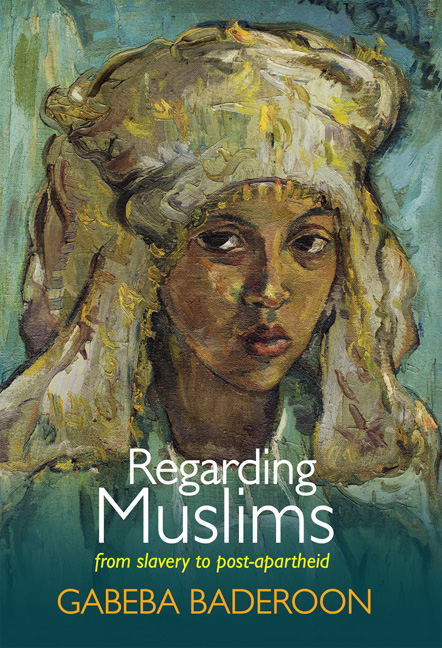

Chapter 5 - Regarding Muslims: Pagad, masked men and veiled women

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 April 2018

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Introduction: Beginnings in South Africa

- Chapter 1 Ambiguous Visibility: Muslims and the making of visuality

- Chapter 2 “Kitchen Language”: Muslims and the culture of food

- Chapter 3 “The Sea Inside Us”: Parallel journeys in the African oceans

- Chapter 4 “Sexual Geographies of the Cape”: Slavery, race and sexual violence

- Chapter 5 Regarding Muslims: Pagad, masked men and veiled women

- Chapter 6 “The Trees Sway North-North-East”: Post-apartheid visions of Islam

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

- Plate section

Summary

Photography is worse than eloquence: it asserts that

nothing is beyond penetration, nothing is beyond confusion,

and nothing is veiled.

– Paul Morand quoted in Alloula (1986: 37)In this whole history of Pagad in South Africa, what stands out

for me is not a media moment but a real event which has the

colourings of a media event … There was a [funeral] procession

just down my street. There were probably three thousand people.

To me, growing up Muslim, it's not an oddity. But suddenly it

brings to my attention that [to my neighbours] it's like a CNN

report coming to life in some vague Arabic country.

– Rustum Kozain (2000: interview)The front page of the Cape Times on Monday 5 August 1996 was called “the most dramatic front page in the long history of the [newspaper]” (Spencer-Smith, quoted in Vongai 1996: 2). The emergence of Pagad into national and international prominence through images of masking, violence and militancy interrupted the longstanding picturesque tradition and changed the way Muslims would be portrayed in South Africa. Media coverage on that day and in succeeding weeks struck me not only as a story about the group called Pagad, but as a new idiom for representing Islam in South Africa. This chapter returns to the “recursive beginning” of images of Pagad in the mid-1990s and places them in the context of the growing force of menacing images of Muslims, an effect resulting both from local dynamics in South Africa and the power of a global imaginary about Islam. The unique local trajectory of images of Islam I have traced in the preceding chapters has nevertheless had moments of strong cross-fertilisation with transnational debates. This was particularly true in the period after the end of South Africa's cultural isolation in 1994, when the South African media became interpelated into international discourses about democracy, “freedom”, “terror” and Islam.

My interest in Pagad was prompted by the set of highly gendered photographs of the group that appeared in the media, tilting the oscillating pattern of images of Islam in South Africa from the picturesque in the direction of violence and alienation. The central image in these narratives was the masked man – an image that soon became indispensable to telling the Pagad story, and which required the erasure of the significant female leadership and membership of the group.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Regarding Muslimsfrom slavery to post-apartheid, pp. 107 - 132Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2014