Popular radicalism was the creature of print. It coincided with a period when newspapers, periodicals, and pamphlets, not to mention the theatre, promised to open politics up to the scrutiny of a wider public than had hitherto been known. Print was also literally understood to offer the opportunity to make a name for one’s self. The pages of the World made Robert Merry a celebrity as the love poet ‘Della Crusca’. He put this fame aside in 1790 to write high-flown odes on freedom under his own name, but continued to purvey newspaper satires in the cause of reform, either anonymously or as ‘Tom Thorne’ in the Argus. But he was not simply free to remake himself in any way he chose. ‘Robert Merry’ was denied the right to the ‘freedom of the mind’ he asserted in his poetry when he put his name to the service of popular radicalism. To write in this cause was deemed by the conservative press to be resigning the independence only a gentleman could presume to own. ‘The poet and the gentleman vanished together’ to become a creature of print in a sense his former friends thought entirely servile.1 Merry did eventually find a realm of comparative freedom in the United States shortly before he died in 1798, aged only forty-three, although even there his name drew opprobrium from loyalists like William Cobbett, who represented him as ‘poor Merry’, a man whose political enthusiasm had forced him to sacrifice his independence to the theatrical career of his wife.

Odes, dinners, toasts, and plays

On 14 July 1789, ever the cosmopolitan, Robert Merry was in Switzerland, taking a break from the reputation he had created as ‘Della Crusca’. Two weeks later, he wrote a melancholy poem ‘Inscription written at La Grande Chartreuse’. When it was published the following year, it appeared simply over the name ‘R. Merry’.2 The Della Cruscan craze had been incubated in a period of exile in the early 1780s, when Merry had struck up a friendship with various literary figures, including Hester Lynch Piozzi.3 Piozzi continued to keep an eye on his career, although she was on the watch for deficiencies of character and increasingly despaired of his radical politics. In January 1788, she had written in her journal:

Merry is a Scholar, a Soldier, a Wit and a Whig. Beautiful in his Person, gay in his Conversation, scornful of a feeble Soul, but full of Reverence for a good one though it be not great. Were Merry daringly, instead of artfully wicked, he would resemble Pierre.4

The mention of Pierre, the conspirator from Otway’s Venice Preserved, a play that proved to be controversial in the 1790s, hints at the subversive proclivities of a man who Piozzi understood as unmoored from any stake in his country’s established order. Over the winter of 1788–9, Merry dabbled in the print politics of the Regency crisis. His ode on the recovery of the king – co-written with Sheridan and recited by Sarah Siddons for a Subscription Gala at the Opera House on 21 April – was an exercise in opportunism that he tried to disown, at least to Piozzi.5 The French Revolution gave him a new direction, although the ‘Inscription’, written in July 1789, only returned to themes that had run through his earlier poetry: the condemnation of the hierarchies of the old order (‘the sumptuous Palace, and the banner’d Hall’); the illusions of Christianity (’deluded monks’), and the need for writers to champion the cause of liberty (‘But still, as Man, assert the Freedom of the mind’). Such commonplaces of the European republic of letters were easy to write in 1789, but whether they were to translate into anything more was the challenge of the Fall of the Bastille.

Perhaps the first substantial expression of Merry’s intention to take up this challenge was The Laurel of Liberty (1790), the poem that appeared under the name ‘robert merry, a. m. member of the royal academy of florence’. Published by John Bell, ‘bookseller to His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales’, and at this stage at least, owner of the World, there was no necessary break here with the world of the Whig and the wit. The elegant format of the slim volume hints at Merry’s connections in the bon ton, but its dedication is ‘to the National Assembly of France the true and zealous representatives of a Free People, with every sentiment of admiration and respect’.6 Around this time, Merry started to lose interest in his connections with the World. Merry and its editor Edward Topham had shared a mutual interest in the Literary Fund in 1790, but Topham was soon begging Becky Wells, the actress who effectively managed the paper for him, to do what she could to keep Merry on board: ‘In regard to public business, you must see Merry, for he appears to me now to be doing nothing.’7 More telling of Merry’s direction of travel at this point were those he joined on the board of the Literary Fund, including David Williams and Godwin’s friend Alexander Jardine. The change was also registered in the reception of his writing. Despite some reservations about the ‘pomp of words’ in the Laurel of Liberty, the Monthly and Analytical reviews were becoming enthusiastic supporters of his work. In November 1790, Horace Walpole’s traced Merry’s political enthusiasm to ‘the new Birmingham warehouse of the original maker’. ‘Birmingham’ here is a metonym for Joseph Priestley and Dissent more generally. By 1793 the author of Political Correspondence or Letters to a Country Gentleman – tellingly a Joseph Johnson publication – could feel confident enough to list Merry among the ‘ablest pens … employed, on this occasion’, Priestley among them, ‘in vindicating the cause of Truth and Liberty’.8

Merry’s political enthusiasm always had to contend with his need to generate an income sufficient to support a fashionable lifestyle. Although he began to publish over his own name in the early 1790s, his social status and independence were threatened by his precarious financial position. Having squandered his inheritance in the 1770s with profligate habits he never entirely forsook, Merry was necessarily invested in the career open to talents, but underpinned by an assumption that he was in the vanguard of an aristocracy of nature. John Taylor had a straightforwardly economic account of Merry’s trajectory in this regard:

Merry was in France during the most frantic period of the French revolution, and had imbibed all the levelling principles of the most furious democrat; having lost his fortune, and in despair, he would most willingly have promoted the destruction of the British government, if he could have entertained any hopes of profiting in the general scramble for power.

Despite their political differences, Taylor frequented the same circle of wits that scribbled for the press. Given that Merry repudiated him as ‘the reptile oculist’ in the Telegraph in 1795, Taylor’s judgements were far from impartial, but he does indicate the way financial need coupled with political belief to force Merry to try a variety of experiments with print politics.9

Perhaps the most unlikely of these experiments was A Picture of Paris, a pantomime written in collaboration with Charles Bonner and the musician William Shield. Presented at Covent Garden on 20 December 1790, its plot shadowed the events of the French Revolution up to the Fête de la Federation of 14 July 1790, promising ‘an exact Representation of … the grand procession to the Champs de Mars … the whole to conclude with a Representation of The grand illuminated platform … on the Ruins of the Bastille’.10 The climax is the Federation Oath where Louis XVI swore to use the powers delegated to him by the National Assembly to maintain the new constitution. The theatre historian George Taylor sees the production as eager to present the Fête as consonant with British liberty. Building on the fact that the Lord Chamberlain licensed the piece, Taylor concludes ‘that the authorities in England shared the belief of French moderates that the Fête marked the end of the French revolution’.11 David Worrall rightly suggests that Taylor neglects the fact that the script would not have given Chamberlain too much sense of what happened on stage in the pantomime.12 Presented only a few weeks after the publication of Burke’s Reflections, A Picture of Paris was entering a rapidly changing scene. The Argus (20 December 1790) thought that ‘the Managers of the house deserve equally the thanks of the several authors, and of the public at large, for the uncommon liberality displayed in the getting up every scene of this Piece’, but then its editor, Sampson Perry, was a sworn enemy of Pitt’s. In its review of the pantomime, The Times (20 December 1790) questioned ‘the propriety of such scenes on British ground’. The theatre, it thought, ought ‘to steer clear of politics’. British liberty, it insisted on 30 December, was quite distinct from what had been celebrated on the Champs de Mars:

We should be glad to be informed what reference the statues of Truth, Mercy, and Justice, exhibited in the new Pantomime of the Picture of Paris, has to the subject of it. – Surely the author of this incoherent jumble of ideas does not mean to affirm that the Revolution in France is founded on any of these godlike virtues.

Unquestionably, The Times continued, representation of a monarch as merely the delegate of the National Assembly did not pass muster with George III: ‘As far as we could collect from looks, the Royal Visitors were certainly not of the opinion with sterne in the instance of debates at least – that “They manage these things much better in france”.’

Merry was starting to exploit any means he could to disseminate his enthusiasm for the Revolution. The preface to the Laurel of Liberty (1790) attacked complacent members of the elite ‘so charmed by apparent commercial prosperity, that they could view with happy indifference the encroachments of insidious power, and the gradual decay of the Constitution’. He was confident that the ‘progress of Opinion, like a rapid stream, though it may be checked, cannot be controuled’.13 If Merry represented ‘Opinion’ as an occluded species of print determinism here, he was also doing everything possible to shape it through the newspapers. He told Samuel Rogers in 1792 that Sheridan had asked him to write for the Morning Post during the Regency Crisis: ‘No man can conceive says he the effect of a daily insinuation – the mind is passive under a newspaper.’14 Merry was already aware of print magic as a dark art and not one to which he readily put the name of ‘Robert Merry’. In 1794, Godwin recorded that ‘Sheridan fills Merry’s hat full of arrows’, that is, Sheridan was feeding Merry with information to use as anonymous newspaper ‘paragraphs’.15 Usually biographical information of one sort or another, blackmailing or satirical ‘paragraphs’ were frequently used as political weapons. Writing in 1803, David Williams traced the use of ‘fleeting arrows’ to Fox’s manipulation of the newspapers to bring down the ministry in 1783.16 Plenty of the insider gossip useful to paragraph writers circulated at theatrical clubs where Merry mixed with Sheridan, Taylor, and others. By early 1792, however, Merry was starting to make radical connections beyond this world and becoming what his friend Samuel Rogers, not altogether approvingly, described as ‘a warm admirer of Paine’.17

Merry’s name added lustre to the political dinners discussed in Chapter 1. His Ode for the fourteenth of July – again elegantly published by Bell – was written for performance at the dinner for the friends to the French Revolution held at the Crown and Anchor, as we saw earlier. The festivities were presided over by the Whig MP George Rous. William Godwin seems to have been there, but only as part of the crowd. By this stage, the World was no friend to Merry. He was probably intended as a target of its hostile description of the diners as ‘men whose profligacy has become proverbial – whose fortunes are desperate, and whose minds are daring and corrupt’.18 The remark may have been provoked by a provocative jibe at his former colleagues in the opening stanza of the ode:

The pun on the name of the newspaper may affirm Merry’s new disposition towards an audience beyond the fashionable daily, but more generally the ode retains the high poetic mode of the Laurel of Liberty. This was the poetry of liberty to which Merry lent his proper name. The ode, especially the stanzas celebrating the ‘animating glass’ discussed earlier in the context of the dinner, was reprinted in the newspapers soon after it was performed and later in various anthologies.20 It provided a vibrantly positive rebuttal of Burke’s fear of electric communication everywhere, but sublimates the medium of print it wishes to exploit into an immediacy that moves from ‘hand to hand’ and then from ‘soul to soul’. In its obituary for Merry in 1799, the Monthly represented him as ‘one of those susceptible minds, to which the genius of liberty instantaneously communicated all its enthusiasm’.21 In the poetry published in his own name, Merry continually presented himself as the authentic conduit of this genius of communication overleaping the complicated terrain of print transmission.

Neither Merry’s reputation for homosocial conviviality, nor the popularity of his ode, protected him from the charge that he was losing his identity as a gentleman in his new political personality.22 On the contrary, he seemed in some quarters to be daringly dispersing his social identity into the mob through the medium of print. In his satires the Baviad (1791) and Maeviad (1795), William Gifford spatialised Merry’s poetry as a ‘Moorfields whine’.23 The tendency of his journalism, not issued over his own name, was also starting to trouble those who wished for moderate reform under aristocratic leaders. At the end of November 1791, Fox reportedly complained that ‘our newspapers … seem to try & outdo the Ministerial papers, in abuse of the Princes, the Morning Chronicle is grown a little better lately, but the others are intolerable, the Gazeteer [sic] particularly, Mr Merry has got that I am told’.24 Merry was certainly still networked into the overlapping worlds of newspapers and theatre. The Times noted (10 January) that a new comic opera called The Magician No Conjuror was in rehearsal at Covent Garden.25 The play did not appear until 2 February, but ran for a respectable four nights, garnering Merry a substantial benefit. The songs sold in pamphlet form, and remained popular enough to be republished in periodicals and anthologies over the course of the year.26 The plot is a standard tale of young love thwarted by old foolishness in the guise of Tobias Talisman, who has retreated to the country to practice the art of necromancy, keeping his daughter Theresa under close confinement. The Gothic possibilities of the female incarceration plot were a favourite of Merry’s, one he scouted in his first play the tragedy Lorenzo (1791), where the heroine is forced into a loveless marriage by her father, and even earlier in A Picture of Paris where it is played for comedy. Much of his writing fantasises about the release of female sexual energies into the arms of a hero somewhat like himself. The hero’s victory in the Magician – where the incarceration plot is again given a comic twist – is guaranteed when he saves Talisman from a resentful mob. There seems to be a loose commentary here on the role of the government provoking the loyalist mob against Priestley, with Merry projecting an idea of himself as the dashing saviour of the situation for the benefit of all.

Most of the newspapers expressed a dim view of the proceedings in their 3 February editions.27 Werkmeister believes that Thomas Harris, the manager of Covent Garden, stopped the play because of its ‘stinging ridicule of Pitt, who, it was all too evident to the audience, was in fact “The Magician”’.28 Although she provides little evidence for this assertion, the idea of Pitt as a conjuror was familiar from earlier Opposition satires. Political Miscellanies (1787) compared him to the popular Italian conjuror Signor Guiseppi Pinetti who had performed in London from 1785.29 Contemporary newspaper commentary does not seem to confirm so specific an identification, but it is clear that responses to it were ideological in general terms. The Earl of Lauderdale’s support for the play, for instance, was noted in the press. Anne Brunton, married to Merry early in 1792, was not re-engaged at Covent Garden after the 1791–2 season, despite her great success in Holcroft’s the Road to Ruin in the spring. By this stage, anyway, the couple were being increasingly drawn towards France. Merry was throwing himself into the radical societies and writing for the radical newspaper the Argus rather than the fashionable pages of the World.

Political societies, 1792–3

‘The Argus is the paper in their pay’, wrote an informer on an LCS meeting at the end of October 1792, ‘and they will have nothing to do with any other.’30 Although the Argus increasingly supported the LCS, its closest relationship was with the SCI. On more than one occasion the Society ordered a copy of the paper to be sent to each of its members. Paine, Horne Tooke, and Merry, who joined the SCI in June 1791, all wrote for it; ‘in short’, remembered Alexander Stephens, ‘it was the rendezvous of all the partizans and literary guerillas then in alliance against the system of government’31. Perry had launched the Argus in 1789 as editor and proprietor: ‘a scandalous paper’, reported the Gentleman’s Magazine in his obituary, ‘which, at the commencement of the French revolution, was distinguished for its virulence and industry in the dissemination of republican doctrines’.32 The Argus certainly insisted that the political elite was betraying the people in terms that echoed Merry’s Laurel of Liberty: ‘You have suffered your Constitution to be gradually invaded, till you are now reduced to a state of the most abject slavery.’33 Pitt was the target of particularly fierce attacks, not least from the satires Merry published in the paper as Tom Thorne:

On 8 May 1792, the same day it printed this squib, the Argus published a paragraph arguing that ‘the present House of Commons … is not composed of the real representatives of the people’. An ex officio information was served on Perry for libelling the House of Commons within the fortnight.

Perry was still in the King’s Bench serving time for previous libels. The date of his release is not clear, but Merry and Perry seem to have collaborated on the paper from at least spring 1792. The poet had successfully proposed Perry’s SCI membership in April 1792.34 ‘During the last months of that paper’s existence’, remembered Merry’s obituarist in the Monthly Magazine, ‘a certain rose was never without a thorne’. The reference was to the controversy surrounding George Rose’s management of elections for Pitt, a row that the Argus covered closely. Merry’s obituary reprinted several of his contributions:

and

The loyalist press even tried to appropriate the Tom Thorne pseudonym to Merry’s evident delight:

The appropriation of the ‘tom thorne’ pseudonym by loyalist newspapers points to difficulty of controlling such shape-shifting productions. ‘His native power’, observed Merry’s obituary, ‘flames out in his odes’, assigning his authentic voice to the poetry that came out under his own name.36 Perry finally fled to Paris before his trial commenced on 6 December to the glee of the World:

The Sampson of the Argus was found too weak to carry off the pillars of the Constitutional Fabric, although he made several ineffectual attempts.37

There he rejoined his colleagues from the SCI, Merry and Paine, among the group of expatriate radicals that met at White’s Hotel. 38

Over the course of 1792, Merry had traced his own uneven course from the Society of the Friends of the People to this much more radical set of associates, some of whom had made similar journeys. Merry’s name is included in the list of those who signed up at the first meeting of Charles Grey’s group of reform Whigs on 11 April, but does not re-appear in later accounts of any of their meetings.39 By May 1792, Grey’s Society had become emphatic in repudiating any association with Paine. On 28 May, Godwin’s diary records that his friend Holcroft was dining with Paine and Merry, although he seems not to have met the poet by this stage himself. Merry was at the SCI on 1 June, when the society received a letter from the LCS recording its ‘infinite satisfaction to think that mankind will soon reap the advantage …[of] a new and cheaper edition of the Rights of Man’. SCI minutes show Merry to have been a very visible presence in the intense period of cooperation between the two societies.40

Merry was working equally hard to open channels of communication between the British and French societies. The Oracle of 15 June reported that ‘Mr and Mrs. merry have taken the Laurel of Liberty with them to France. – The Poet presents his Ode to the national assembly.’ Sounding a note that was to echo across many hostile accounts of Merry that followed, the paper commented: ‘The merry poet has now dwindled into a sad politician!’41 On 28 September, he was present at the SCI meeting when another LCS letter proposed a supportive address to the National Convention. Merry was elected to the committee asked to consult on a joint version. In the same month, he also seems to have begun actively supporting the French move towards a republic in the British press. Advertisements appeared for an apology for the August days and the September Massacres: “a particular account of the Rise, and also of the Fall of Despotism in Paris, on the 10th of August, and the Treasons of Royalty, anterior and subsequent to that period. By Robert Merry, Esq.” I have not been able to trace any pamphlet under this exact title, but it may be A Circumstantial History of the Transactions at Paris on the Tenth of August, plainly showing the Perfidy of Louis XVI. LCS members Thomson and Littlejohn published it from their Temple Yard press with H. D. Symonds. Symonds was given as the publisher of the Merry pamphlet advertised in the newspapers.42

In October, Merry wrote from Calais to his ‘friend and fellow labourer’ Horne Tooke to tell him that the armies of the Republic needed shoes more than muskets.43 In Paris, Merry seems to have been part of the most radical faction of the British Club – opposed by John Frost – calling on the Convention to invade Britain and provoke a popular uprising in support. Frost thought it a misjudgement of the political mood in Britain. Merry’s universal enthusiasm for a democratic republic extended to making his own proposals for the new constitution of France. His obituary in the Monthly Magazine mentions ‘a short treatise in English, on the nature of free government … translated into French by Mr Madget’, almost certainly Merry’s Réflexions politiques sur la nouvelle constitution qui se prépare en France, adressées à la république (1792).44 Understandably enough never published in Britain, Merry’s pamphlet calls for popular participation at every level of the political process, recommending a role for primary assemblies in confirming laws (an issue debated in France that found an echo in LCS discussions of the relation of the divisions to the central committee). There is also a section on the neglect of literary men under despotism, a personal concern expressed in his work for the Literary Fund. The pamphlet leaves the reader in no doubt that Merry thought Britain just such a despotism. Merry shows little patience for the mixed British constitution. The proposed constitution is based on the classical virtues of an active citizenship. If its foundations were formed by a classical education under Samuel Parr, then the pamphlet was unequivocal about the democratic example of France as the only hope for the regeneration of Britain.

Internal exile, Godwinian, and satirist

At the end of 1793 the European Magazine published a pen portrait of Merry:

Having passed the greater part of his life in what is called high company, and in the beau monde, he became disgusted with the follies and vices of the Noblesse, and is now a most strenuous friend to general liberty, and the common rights of mankind.45

Compared with most accounts of Merry published by the polite press in 1793, this one is curiously sympathetic. By the time it appeared in print, Merry had been back in Britain for nearly six months. As France under Robespierre became increasingly suspicious of foreigners, the situation had become hostile for cosmopolitan radicals who had made the pilgrimage to the Revolution. His friends Paine and Perry were in prison in Paris. Merry had managed to get back to London in May with the help of Jacques-Louis David.46 Having kept their readers apprised of Merry’s activities in France, the English newspapers took particular delight in retailing the story of his retreat back to Britain, but other circles were making Merry more welcome. Godwin’s diary records that he and Holcroft dined with Merry on 11 August, but despite these budding support networks Merry had no obvious source of income and the derision of the press must have made life in Britain insupportable. He borrowed money from Maurice Margarot against a bill for £130.47 In September, Merry decided to flee for Switzerland with his wife and Charles Pigott, funded by a bank draft for £50 from Samuel Rogers. On 2 September, still keeping their erstwhile star contributor under surveillance, the World reported that the trio had crossed to the continent. The information was false. They had turned back at Harwich before even boarding ship.

Merry separated from Pigott and retreated to Scarborough. He wrote to Rogers asking for more money and begged that his presence be kept secret, but by mid-October the newspapers had found him out.48 Merry outlined his current projects in a series of nervous letters to Rogers and asked for help finding publishers. He seems to have been in a state of shock, not least about the prospects for political change. On 3 November, mentioning fears that his letters were being opened, he was writing an ‘Elegy upon the Horrors of War’. A month later, he provided an insight into the mental turmoil caused by the dashing of his political hopes:

Yet still am I troubled by the Revolutionary Struggle; the great object of human happiness is never long removed from my sight. O that I could sleep for two centuries like the youths of Ephesus and then awake to a new order of things!

Then on 18 December, Merry sends ‘a little theatrical Piece, which I mean to conceal being Mine not to be exposed Aristocratical Malice’. He described it as ‘a free translation of the French Play, of Fenelon, reduced to three Acts’, but suspected its subject and his name would prevent it being staged:

I do not suppose it will be performed, on account of its coming from that democratic country … if you think it has any merit – get it published for me I beg of you not to mention my being the Translator in case it should be played – as the name of a Republican would damn any performance at this time.49

The Godwin circle provided succour in these difficult months. Merry appears regularly in Godwin’s diary from summer 1794, especially in the vicinity of the radical stronghold of Norwich. Anne Brunton had family connections with the area. Her father, John Brunton, managed the theatre. Thomas Amyot reported Merry’s presence there in May.50 By 15 June at least Merry was ranging further afield, dining with Godwin and Holcroft in London. Merry also started to exert a particular fascination on Amelia Alderson, brought up in these Norwich circles. Her ‘curiosity’ was raised ‘to a most painful height’ when in 1794 Charles Sinclair revealed that Anne Brunton was a ‘firm’ democrat and ‘a great deal more’. Two years later, in November 1796, she admitted to Godwin

Poor Merry! – Will you not wish to box my ears when I venture to say, that I do not think his mind at all matched in his matrimonial connection? Mrs. Merry appears to me a very charming actress, but, but, but – fill it as you please.

Godwin seems to have been scarcely less fascinated, particularly by Merry’s connections with Sheridan and his easy facility as a writer. ‘Mr. Merry boasts that he once wrote an epilogue to a play of Miles Peter Andrews, while the servant waited in the hall’, he told Wollstonecraft in 1796, ‘but that is not my talent.’51 According to his diary, on 26 June Godwin read an ode by Merry. Two days later, the pair dined at the Alderson home in a company associated with Norwich radicalism. Merry read to Godwin ‘specimens of 2 novels’ on 30 June. Merry’s pressing need to make money from his writing drew scornful commentary in the press. Former friends like Piozzi described him as begging for subscriptions, but Godwin seems to have taken his talk seriously, listening to his opinions of Political justice while revising it in July 1796.52 Quite possibly Godwin also helped Merry place his final major poem, Pains of Memory (1796) with his publishers, the Robinsons. During this period, Holcroft wrote a joshing letter to Godwin mentioning ‘our good friend Robert Merry, once an [sic] squire and now a man’, pointing up the poet’s social and political journey from Whig gentleman to radical democrat.53 If Holcroft was celebrating a political butterfly emerging from the pupae of the fashionable Whig, then the oncoming treason trials were reason for alarm to both men. Merry’s name appeared in the SCI minute books used as evidence in the prosecutions of Hardy and Horne Tooke.54 On 11 October, Merry told Rogers that ‘existing circumstances … appear to me hastily advancing to some great catastrophe’. Only four days earlier, Holcroft had surrendered himself in to the court. ‘As things now stand’, Merry told Rogers, ‘I feel some inclination for going with Mrs. Merry to America, and perhaps if I should do so you would put me in a way how to proceed.’55

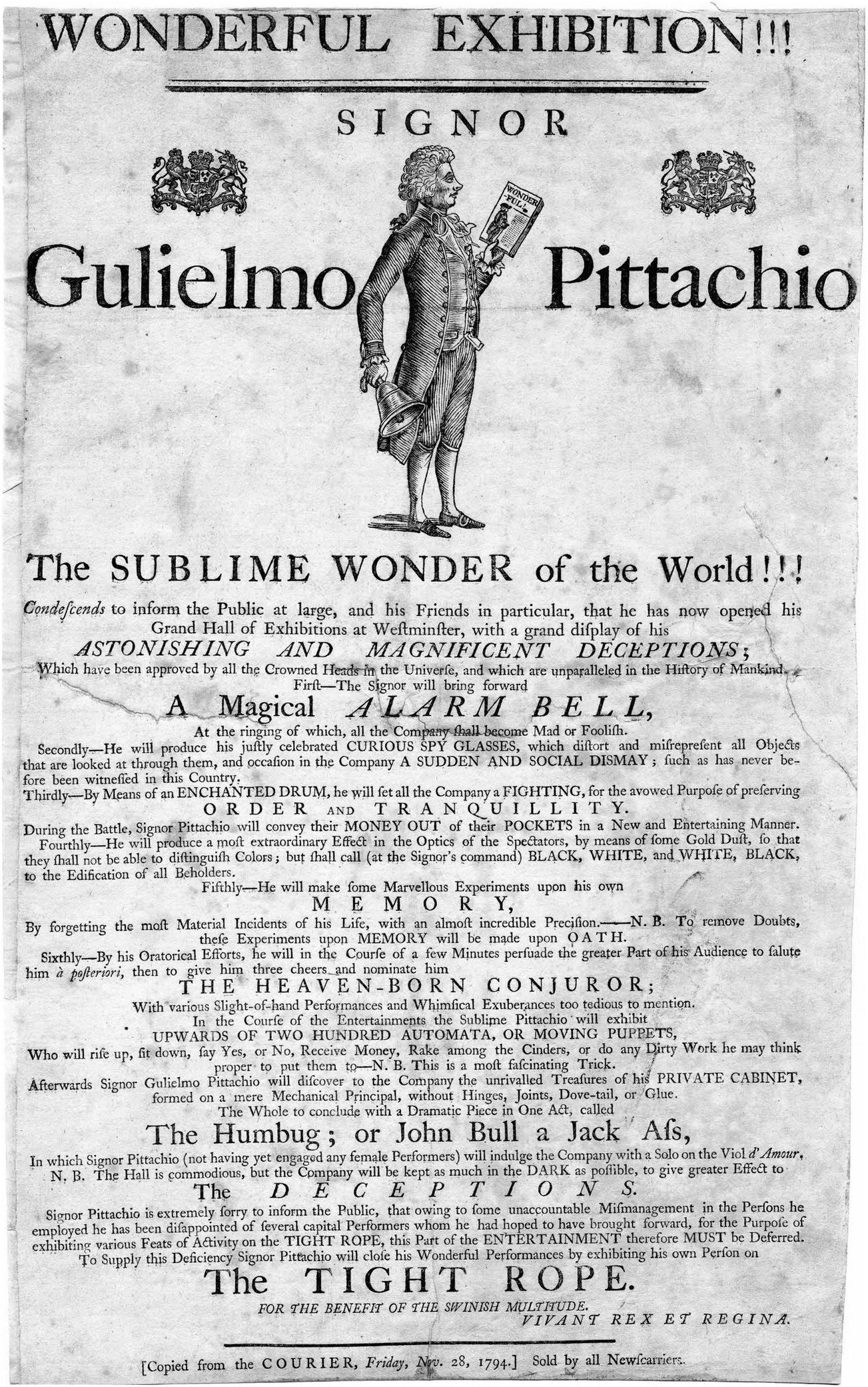

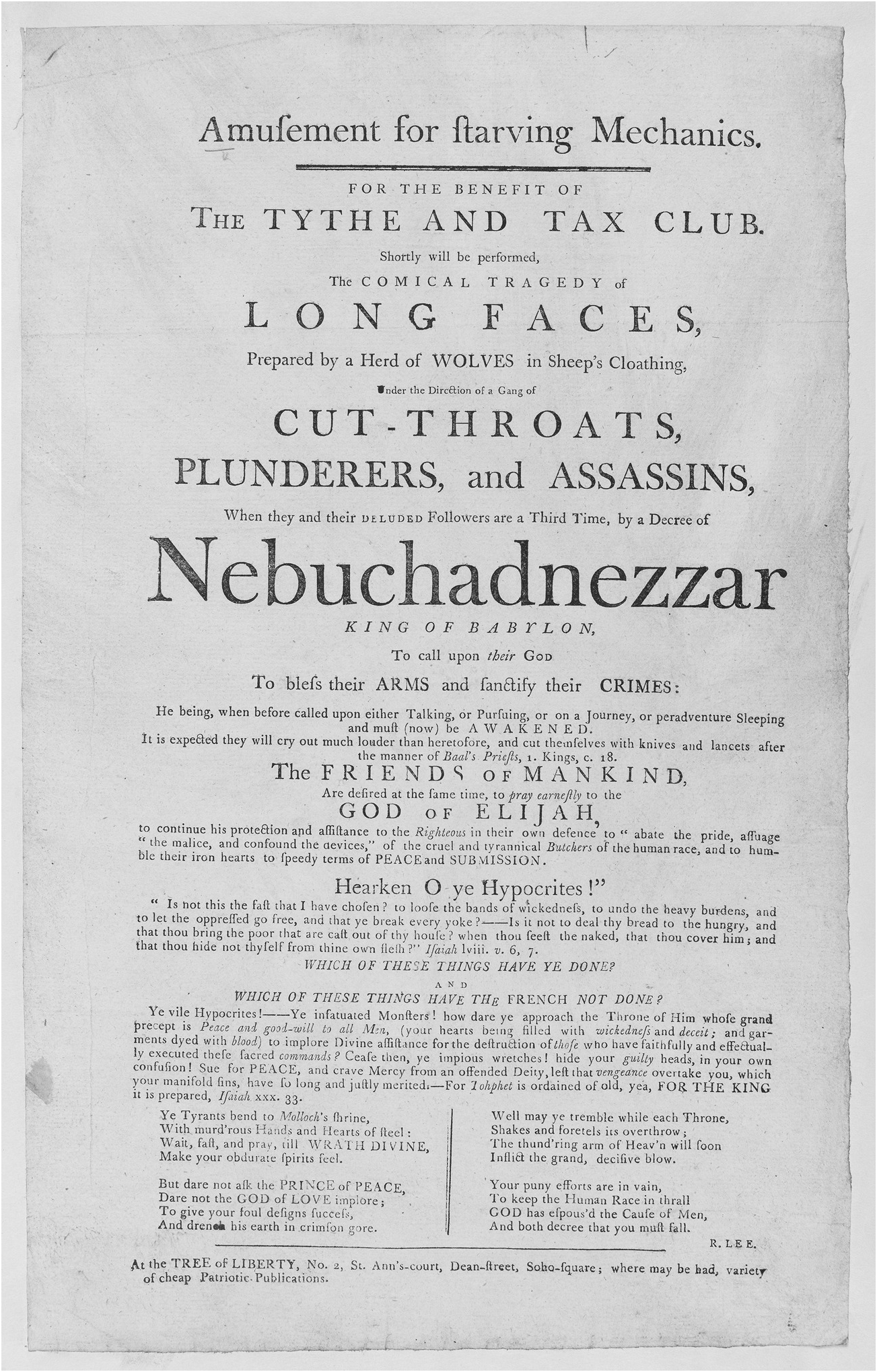

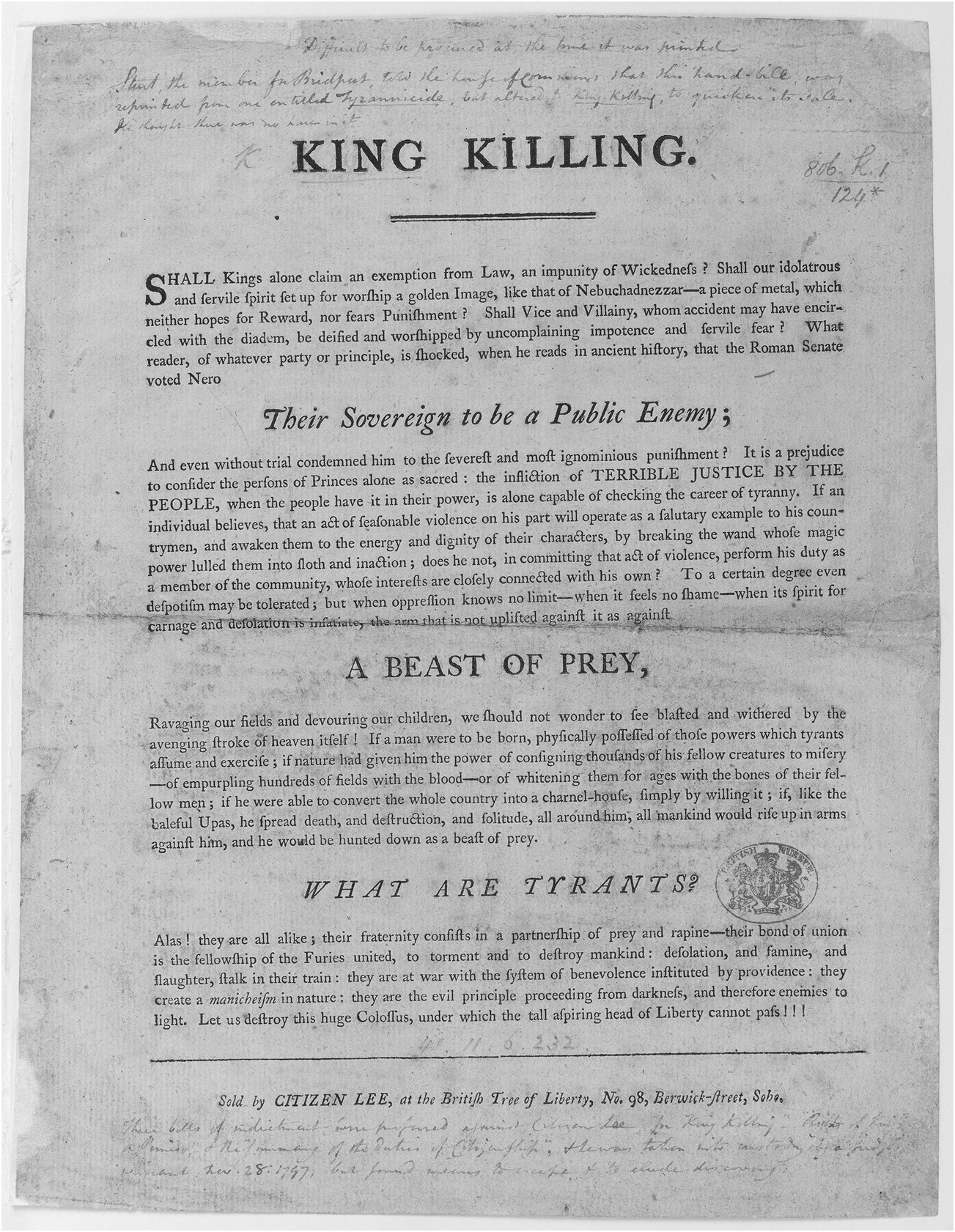

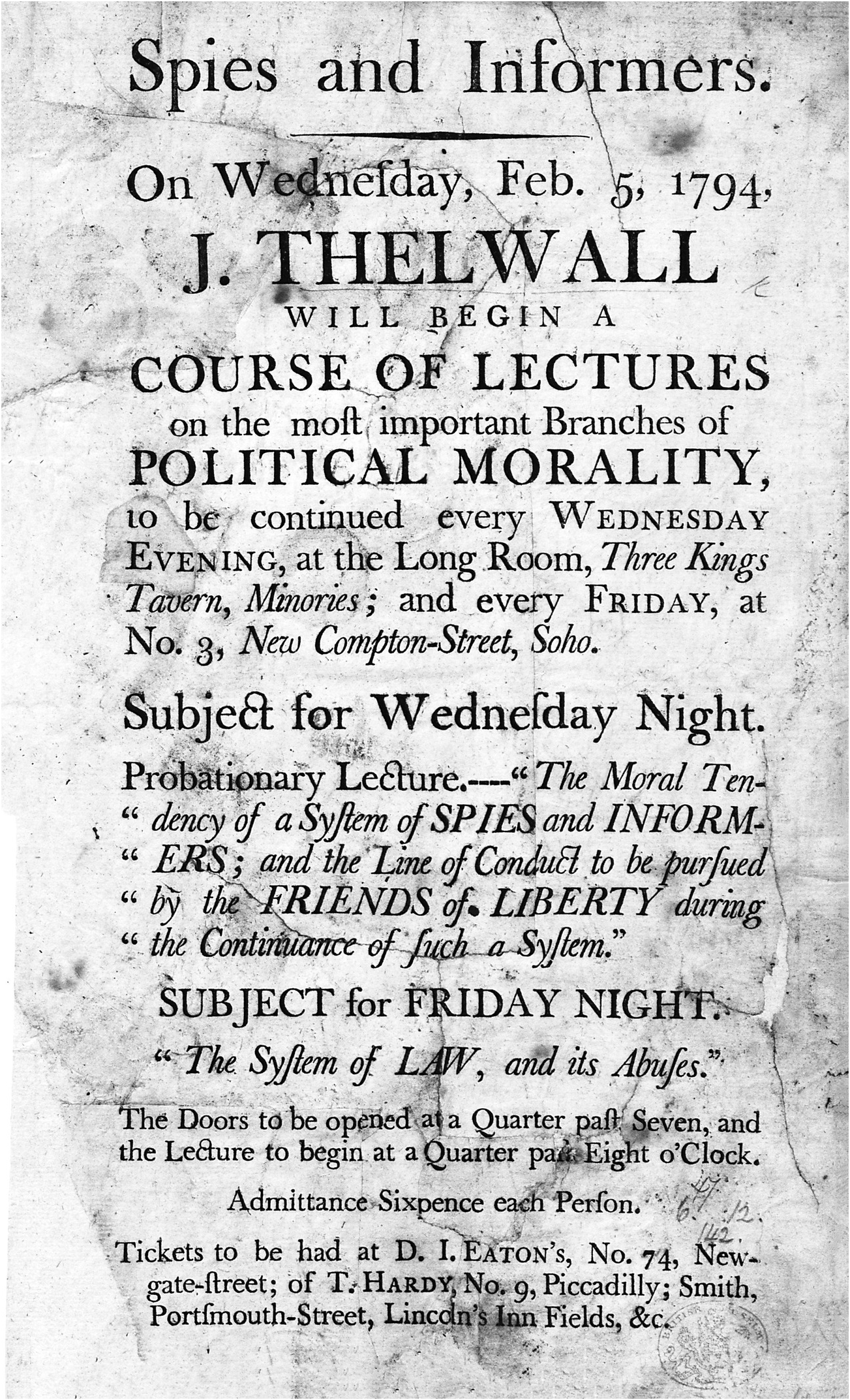

The acquittals of Hardy and Horne Tooke seem to have given Merry a new lease of life as a satirical journalist, just as they powered a surge of activity in the LCS. Although it is impossible to know exactly what part he played in the cheap productions that poured off the radial presses in 1795, he was remembered long afterwards for the great triumph of Wonderful Exhibition!!! Signor Gulielmo Pittachio, the first in a series of pasquinades that followed the acquittal of Horne Tooke on 22 November (Figure 5). ‘No minister in any age had been so ridiculed before’, Merry’s obituary in the Monthly remembered. First appearing in the pages of the Courier on 28 November, Pittachio exploited a trope that went back to the Political Miscellanies (1787) and Merry’s own Magician no Conjuror (1792).56 Developing the satire on Pitt’s ‘surprising tricks and deceptions’ from Political Miscellanies, Pittachio presents Parliament in thrall to Pitt’s ‘magical alarm bell’:

upwards of two hundred automata, or moving puppets, Who will rise up, sit down, say Yes, or NO, Receive Money, Rake among the Cinders, or do any Dirty Work he may think proper to put them to.

‘Unaccountable mismanagement’ means Pittachio is unable to bring forward ‘several Capital Performers … for the Purpose of exhibiting various Feats of Activity on the tight rope’. Pitt had not been able to manage the guilty verdicts against Hardy and Horne Tooke, but the satire ends by flipping this scenario and imagining that he would instead ‘close his Wonderful Performances by exhibiting his own Person on the tight rope for the benefit of the swinish multitude’. The Pittachio series was part of a proliferating number imagining the Prime Minister being hanged for his crimes against the people.

Fig 5 Wonderful Exhibition!!! Signor Gulielmo Pittachio (1794). Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved.

The most striking of these were the death and dissection of Pitt satires that appeared first in the Telegraph in August 1795. Whether Merry had a hand in these is unknown, but on 27 June 1796 Godwin recorded visiting the offices of the Telegraph, where he found ‘Merry, Este, Robinson, Chalmers & Beaumont’. Founded in December 1794, the Telegraph had succeeded the Argus and joined the Courier as the most radical of the English dailies.57 Merry’s obituary in the Monthly Magazine claimed ‘some of the best poetry in the Telegraph was the production of his pen’.58 D. E. MacDonnell, the editor, acted as go-between for Merry with John Taylor in the dispute over the satirical paragraph attacking ‘the reptile oculist’.59 If Merry didn’t write the Death and Dissection of Pitt satires, then he was certainly in the thick of the group of collaborators closely involved in the Telegraph where they first appeared.

Fenelon and The Wounded Soldier – the play and the poem he had told Rogers about late in 1793 – were also published in 1795. Fenelon was never produced, but it was published under Merry’s name and dedicated to Rogers. A partial translation of a play by Marie-Joseph Chénier, Fenelon saw Merry return to the Gothic incarceration plot. Release for the heroine is obtained by the intervention of Archbishop Fenelon, an interesting switch from the dashing hero of the Magician. The choice may indicate the shared interests of the Godwin circle, since Fenelon was one of their acknowledged heroes. In Political justice, it is Fenelon who Godwin imagines saving from a fire – in the interests of humanity – in the famous passage that caused a storm over his utilitarian version of universal benevolence. Holcroft’s account of Merry’s play in the Monthly Review began by praising the role of Fenelon’s book ‘in enlightening mankind’.60 Merry was writing The Wounded Soldier at about the same time Wordsworth was first addressing the same themes in his ‘Salisbury Plain’ poems. Hargreaves-Mawdsley notes that Merry's language ‘is like that of a tract ... intended for the simplest reader’. The effect is surely intentional, even if Merry described his poem to Rogers as ‘to avoid offence … very tame’.61

The Wounded Soldier enjoyed a fairly wide circulation, but first appeared as a penny pamphlet from T. G. Ballard, the author’s name appearing only as ‘Mr. M–y’. By 1795 Ballard was becoming one of the LCS’s regular printers, advertising ‘a great Variety of Patriotic Publications’.62 Ballard also brought out a late version of the Death and Dissection of Pitt satire as Pitt’s Ghost (1795). Citizen Lee also published many of the Pittachio broadsides and various editions of the Death and Dissection of Pitt. He attributed one satire – Pitti-Clout & Dun-Cuddy (1795) – to ‘Mr. M-r-y’, but then later acknowledged an error of attribution.63 Lee’s mistaken use of Merry’s name may have been an over-eager attempt to exploit what glamour, at least in radical circles, remained of it. These publications were probably as close to the LCS as Merry came after he returned from France in 1793. 64 He never took sanctuary there, unlike his friend Charles Pigott. Merry may have felt safest among journalists like those in the offices of the Telegraph, or Dissenting literati like the Aldersons, Godwin, and Holcroft. Such groups often flowed into each other, as Godwin’s visit to the office of the Telegraph suggests, but ultimately they could not provide him with a context to continue writing in Britain.

Transatlantic laureate

Merry continued to see Godwin, especially with Holcroft and sometimes with the moneylender John King, financial troubles making Merry’s residence in England increasingly untenable. The pattern of sociability intensified in January and February 1796 – Godwin seems to meet Merry at a Philomath supper on 12 January – and they see each other several times in April and in June, leaving together for East Anglia on the Ipswich mail on 1 July. A week later Merry was arrested for debt in Norwich. Godwin and James Alderson helped extricate him, but the episode may have determined Merry to leave for the United States.65 Although the emigration of the Merrys had been trailed in the press for some time, it still came as a surprise to Godwin and Amelia Alderson when they left in September 1796. Godwin wrote to Merry too late:

Yesterday evening I heard of your expedition, & heard of it with much pain. I could not forget it all night. I cannot endure to think that a man, whom I regard as an honour & ornament to his country, should thus go into voluntary banishment. If you had thought proper to consult me, I would have endeavoured to dissuade you.

Alderson’s letters to Godwin in October and November 1796 advert to the matter more than once. She found it hard to believe that Merry could possibly be happy in the United States:

I wish much to know how he looked & talk'd when he bade you adieu - whether he was most full of hope, or dejection – My heart felt heavy when I heard he was really gone, & gone too where I fear the charms of his conversation, and his talents will not be relished as they desire to be.

Alderson’s estimation of Merry’s chances of happiness was not untypical of opinion even in progressive circles.66 Writing for prospective emigrants in 1794, Thomas Cooper took the view that ‘literary men’ did not yet exist there as ‘what may be called a class of society’.67 The question of whether the new republic could sustain a literary career was an issue Merry had debated for several years before finally deciding to go. He seems to have seriously considered the option at least twice before he set sail: first, in the summer of 1792, according to the actor James Fennell, when Merry expected the forces of counter-revolution to succeed in their invasion of France; secondly, on the eve of the treason trials, when he asked Rogers for advice about the move.68 His friend Holcroft’s opinion that the United States remained ‘unfavourable to genius’ and uncongenial to ‘energy and improvement’ must have weighed on his mind, but his hand was forced by financial necessity compounded by the political context after the Two Acts had passed into law.69

As it transpired, there was literary culture enough to greet Merry’s arrival with great enthusiasm. Della Cruscanism had been and was to continue to be an important influence on the poetry of the early republic. Pains of Memory was to become one of its most reprinted poems and guaranteed that his arrival garnered various poems of acclaim in response:

Fleeing Britain only a few months before Merry, Citizen Lee published these lines in his American Universal Magazine. Not everyone was as pleased to see him. Bristling in the American press as Peter Porcupine, William Cobbett attacked both men as part of a conspiracy intent on spreading Jacobinism to the United States:

Poor Merry (whom, however, I do not class with such villains as the above) died about three months ago, just as he was about to finish a treatise on the justice of the Agrarian system. He was never noticed in America; he pined away in obscurity.71

The last claim is debatable to say the least.

John Bernard knew Merry from his pomp in the convivial clubs of London, but thought he thrived in America, even enjoying the rough and tumble of electoral politics: ‘exposed to actual collision with the crowd … Merry was the only man I knew for whom it had a relish.’72 A page Merry added to the Philadelphia edition of Pains of Memory suggests he saw the possibilities of a democratic literary culture in the new republic:

Merry seems to have been engaged in thinking about these issues when he died suddenly in 1798, leaving behind him his own dissertation on ‘the State of Society and Manners’, addressed to ‘the curiosity of the European reader, respecting the comparative situation of the United States’.74 Over the course of the 1790s, Merry’s experiences in Britain, France, and the United States had given him ample material for such a study. In the process, Thomas Holcroft thought, he laid aside his elite identity as a squire and emerged as a properly independent man. His remaking of himself as he engaged with the implications of the French Revolution was somewhat more complex than Holcroft’s perspective allowed. If the poet and the gentlemen were not entirely sacrificed to the politician, as his enemies proposed, then they did become part of a complex process of self-fashioning in print that ended only with his death in exile.

Few people denied Robert Merry’s charm. Years after his death, John Bernard still celebrated him from among all those who gathered at the Beefsteak Club, Fox and Sheridan included, as the one with the most ‘benevolent mould of mind’.1 This reputation underwrote Merry’s political credentials for many sympathisers, confirming that his character was grounded in right feeling. For others, as we have seen, his political enthusiasm warped and, ultimately, betrayed his sociable nature. Hardly anyone ever made either claim for Charles ‘Louse’ Pigott, despite the fact that he and Merry were friends from similar backgrounds. Pigott had a lasting image as a man who had ‘robbed his friends, cheated his creditors, repudiated his wife, and libelled all his acquaintance’.2 Nevertheless, he made two of the most influential contributions to the popular radical literature of the 1790s. The anonymous The Jockey Club (1792) rivalled Rights of Man, at least in the alarm it spread among the government’s law officers. His posthumous Political Dictionary (1795) was endlessly recycled in the contest over the legitimacy of the traditional language of politics. Both books made great play with the politics of personality without making much of Pigott’s own. He did publish some things under his own name, but never created a print personality after the manner of Merry. ‘Louse’ was the derisive nickname known to the relatively closed circle who shared his elite background. Generally, he proved as adaptive as the insect he was named after, thriving in the crevices of print culture, mixing political theory and French materialism with scandal and blackmail, unevenly espousing a radical politics while continuing to insist on his independence as a gentleman, until the government caught up with him and gaol fever killed him.

Cracking the louse

Pigott was the youngest son of an old Jacobite family whose family seat was the manor of Chetwynd Park, Shropshire.3 His eldest brother Robert was a member of the exclusive Jockey Club, who became High Sheriff of the county in 1774, but two years later sold the family estates and moved to the continent. Robert played a direct role in the political clubs of Paris during some of the headiest days of the Revolution before settling in Toulouse in 1792 (dying there in 1794). Probably an important conduit of French ideas to Charles, his remittances also bankrolled his younger brother, at least until politics in France blocked this supply line. Charles went to Eton and in 1769 matriculated at Trinity Hall Cambridge. Soon afterwards he lost a fortune on the turf, mixing in high-rolling Foxite circles. His friends, Fox among them, apparently subscribed to help him out of debtor’s prison. Nevertheless, Pigott felt free to attack Fox’s pose as ‘Man of the People’. In the first of two letters that appeared in the Public Advertiser in March 1785, he berated Fox for stooping to exploit every ruse available in the unreformed electoral system. Their tone confirmed Pigott’s own status as a gentleman of independent mind even as it mourned Fox’s manipulation of the mob:

In committing my thoughts to the public, I am instigated by no other motives, than, I fear, a vain desire of convincing them of their error, and of lamenting those fatal prejudices in many great and exalted characters which have induced them to display such indecent exultation upon a triumph wherein every sensible dispassionate person, who was an ocular witness to the infamous disgraceful proceedings of the Westminster Election, must be affected with the deepest sorrow and indignation.

The second on Fox’s position on Irish affairs hints at Pigott’s adaptive response to print:

Newspapers are the great extensive vehicles of general intelligence; and as the Public Advertiser is universally read, I have selected that publication as best adapted to my purpose.4

Fox and his friends were ambivalent about newspapers as places to argue out political principles, but they were far from slow to respond to Pigott on the field of satire.5 Between the two letters, the Morning Herald – a vociferous supporter of Fox – published four epigrams, headed ‘Reason for Mr. Fox’s avowed contempt for one pigot’s Address to him’, all playing on the idea of the louse as an inhabitant of a vermin-infested (debtor’s) prison:

Despite these slap downs, an antipathy to the hypocrisy of Fox’s pose as ‘Man of the People’ was to remain a more or less consistent part of Pigott’s rhetoric as he made an uneven and incomplete journey from the elite language of independence to the natural rights arguments associated with Thomas Paine and the French Revolution.

Robert Pigott had published in English on French affairs in the 1780s, including New Information and Lights, on the Late Commercial Treaty (1787), which the Critical Review dismissed as ‘the refuse of political rancour, poured forth with petulance, and in language that violates the plainest rules of English grammar’. In the early stages of the Revolution, he addressed the National Assembly in another pamphlet, also published in English, on the liberty of the press.7 Charles made his first intervention in the British ‘debate’ over the French Revolution in Strictures on the New Political Tenets of the Right Honourable Edmund Burke (1791). Published by Ridgway, it was designed as an answer to Burke’s Appeal from the New to the Old Whigs (1791) and Letter to a Member of the National Assembly (1791). The pamphlet initially presents itself as an attack on Burke’s defection from ‘every idea of friendship and party attachment’, but shows some sensitivity to Pigott’s own vulnerability in this score, given his newspaper letters to Fox. Those attacks, Pigott implied, had been based on policies not persons, but went on to suggest – in relation to the account of Burke – that ‘every trader in politics should be scouted’.8 His most influential contributions to the popular radical cause from 1792 were all to develop just such an unstable mixture of personal muckraking and republican principles for an increasingly popular audience.

Pigott’s representation of Burke as a ‘deserter from an honourable cause’ proposed that ‘the principles that provoked and justified American resistance, are exactly similar with those that brought about the French revolution’. Burke was reneging on a conception of inalienable popular sovereignty that he had defended in the case of the American revolutionaries. These differences might be construed as an in-house dispute about the meaning of the Whig tradition, not least because Burke is represented as deserting the social network associated with Fox, except that as Strictures progresses a different kind of language emerges. Expanding upon the hints in his earlier letters to the Public Advertiser, Pigott dismisses the distinction between Whig and Tory as illusory: ‘From the instant either one or other approach the throne in a ministerial capacity, they must, like camelions, change their natural colour.’9 Even these opinions might be seen as an assertion of pure Whig values, Pigott represents the National Assembly as primarily concerned with the ‘correction of abuses’, but towards its close Strictures starts to invoke Rousseau’s notions of the general will.10 Thomas Paine is lauded as ‘the distinguished and successful rival of Mr. Burke’. The language of traditional rights is to be abandoned in favour of ‘the lights of reason and truth … and … that theory, whose basis is fixed on the natural and untransferable rights of Men and Citizens’.11

Given the French connections he had through his brother, the appearance of this kind of language in Strictures is hardly surprising. Even so, while ‘the natural and untransferable rights of man’ may dominate the later parts of Strictures, it would be misleading to suggest that it entirely effaces the vocabulary of English liberty. Even his later pamphlet Treachery no Crime (1793) is still loath to abandon the idea of the excellence of the original constitution despite the ‘polypuses and rotten excrescencies that have grown upon it’.12 What does newly appear there is the influence of Political Justice, which it quotes regularly, for instance in representing utility – ‘the comparative benefits or injuries which it yields’ – as the best gauge of a constitution. Far less reminiscent of Godwin are the personal attacks in Treachery no Crime on the ‘lazy effeminacy and luxury of courts’.13 Where for the most part Strictures reads as a discussion of political principles, underwritten by the author’s name, Treachery no Crime (1793) – with ‘all the signs of hasty composition’, as the Analytical complained – is full of scurrilous barbs, but it looks like a pale shadow of the Jockey Club, the pamphlet that Pigott had brought out over the course of the previous year. Both were published anonymously, unlike Strictures. If ‘debate’ seems a poor description for the guerilla war being conducted in print over the French Revolution by the end of 1792, then Pigott and the Jockey Club played a major part in the transformation from disquisitions on principles to a fight – with the gloves off – over the legitimacy of the ruling classes.

Riding the aristocracy

Pigott had given notice of a willingness to bring the political elite – of whatever party – to the court of the popular press in 1785. The promise was more than made good in the Jockey Club, published in three parts as it expanded over the course of 1792. Strictures insisted that the author still preserved ‘the utmost respect for the personal and political character of Mr. Fox’.14 The personal affiliations of elite politics survive reasonably intact there, not least because Burke is chastised for reneging on them, but in the Jockey Club, or A Sketch of the Manners of the Age (1792) personal knowledge of the Whig oligarchy as well as the Crown and its allies was used with devastating effect to present the ruling elite as morally bankrupt. Taking the form of a series of brief and deeply scurrilous potted biographies, starting with the Prince of Wales, but moving on to his Whig connections, the Jockey Club proposed to show ‘that a revolution in government, can alone bring about a revolution in morals; while it continues the custom to annex such servile awe and prostituted reverence to those who are virtually the most undeserving of it’.15

Unaware of Pigott’s identity, John Wilde, Professor of Civil Law at Edinburgh University, saw the pamphlet as following an example learnt from the French:

The present state of France is, in no small degree, owing to the calumnies circulated against the higher orders, and especially the criminalities forged against the Court. The same game is playing in this country. No instrument employed in it can be contemptible. Vice certainly ought to be justified no where; among the higher ranks perhaps less than anywhere. But he is blind, indeed, who does not see why real vices are exaggerated against them in this age, and others pretended that do not exist. And that man has, in truth, little foresight who does not see the consequence of such publications being much read and believed.16

Wilde’s assumption was not unreasonable. Pigott had defined his aim as taking ‘the dust out of the eyes of the multitude, in lessening that aristocratic influence which so much pains are now taking to perpetuate’.17 Be that as it may, the patriot idea of a moral crusade in the name of reform in the preface is scarcely preparation for the coruscating and often indecent satire of the sketches themselves. One of the earliest attacks on the Jockey Club, the British Constitution Invulnerable (1792) identified a division of labour between Paine and Pigott: Paine engaged with principles, the author claimed, where Pigott used his personal knowledge of the political elite to attack their persons. An Answer to Three Scurrilous Pamphlets (1792), seemingly written by someone from within or familiar with Pigott’s old gambling circles, provided a much fiercer rebuttal. Using Pigott’s own satirical tactics, personal knowledge of his past is flourished to claim that he had robbed his friends and repudiated his wife. The author chronicles Pigott’s education at Eton, where he was started to be known as ‘Louse’; his political disaffection is represented as the result of an unhappy fashionable marriage and gambling debts; his ingratitude to Fox is framed via an anecdote about the subscription to release him from debtor’s prison. An Answer also claims some paragraphs had first been offered to his victims as blackmail threats: ‘Copies of these libels he has occasionally sent to several ladies; some of whom have deprecated his menaces, with presents of Bank paper.’18

Certainly Pigott was a master of insinuation and titillation. Many who sympathised with the Jockey Club’s politics could not accept its method. Reviewing a fourth edition of Part I in May 1792, the Analytical Review could approve of the political sentiments, but judged much of its content ‘too personal for us to attempt to accompany the author in his biographical sketches’.19 With no sympathy for Pigott’s politics, the author of the British Constitution Invulnerable was much blunter: ‘gross ideas are concealed under equivocal expressions and indecent subjects amplified’.20 Colonel George Hanger was already a staple figure of newspaper gossip and satirical prints.21 The fact that he had been Fox’s agent at the Westminster election of 1784 made him irresistible for Pigott’s amplifications. The description starts relatively mildly: ‘The person in question is admirably calculated to have shone a conspicuous figure in courts, when it was the custom to keep a f—l.’ Typically insults turn to accounts of sexual peccadillos in the Jockey Club. Hanger was no exception:

The M-j-r has of late connected himself with a lady of very amiable accomplishments; – none of your flimsy, delicate beauties; she is composed of true substantial English materials, and what there is plenty of her, cut and come again.22

Many of the entries show a libertine delight in obscene punning that was a familiar part of the masculine ethos of aristocratic clubs. The description of General William Dalrymple, for instance, notes that he had married ‘a young lady who had been much celebrated for the admirable dexterity of certain manual operations, still remembered with a kind of pleasing melancholy by several gentlemen now living’.23

Many of the stories had already appeared in newspaper paragraphs. Wilde assumed that the pamphlet had been ‘pilfered almost entirely from magazines and former scandalous chronicles of the times’.24 Pigott was supplying a ‘daily insinuation’ to the press before he gathered the paragraphs into his book. ‘Characters from the Jockey Club’ appear in the Bon Ton Magazine early in 1792, probably to extort money from their targets. Certainly, Ridgway, one of The Jockey Club’s publishers, had been using this kind of technique for a while.25 Material that later surfaced in the Jockey Club’s paragraphs on Charles James Fox appear without acknowledgement in the April issue of the Bon Ton, but nothing from the two later parts of the Jockey Club, where the affiliation to Painite politics is much clearer. Events in France were regularly featured in the Bon Ton’s pages, but only as warning tales of the violent excesses of the crowd.26 Stories of aristocratic debauchery could be a source of amusement in the Bon Ton Magazine, but when they were hitched to a republican political programme, then it was another matter.

The first part of the Jockey Club, published at the end of February, was relatively mild on Fox and the Whig party. The Prince of Wales is execrated as an example of how ‘disgraceful it is to pay homage to a person merely on account of his descent’, but the possibility that Fox and, especially, Sheridan might live up to their reputations as friends of liberty is kept alive. At this stage still professing an attachment to ‘limited monarchy’, Pigott calls upon Fox to rouse himself, live up to his initial welcome for the French Revolution, and exert himself against the encroachments of the Crown. Pigott sees Sheridan as the more principled of the two politicians. If he lives up to his reputation, ‘he will be adored while living, and his name enrolled on the register of immortality, amongst the most distinguished patriots and benefactors of mankind’.27 The superiority of Sheridan over Fox is more pronounced in the second part, published in May, where he appears as the only politician ‘whose public principles stand unimpeached’. Fox is castigated for his deference to ‘aristocratic connections’.28 The third part written after the events of 10 August and the September massacres in Paris, published on 15 September, is openly republican, beginning, to the astonishment of the Analytical Review, with a deeply unflattering comparison of George III and Louis XVI that implied that the deposition of the latter in August would and ought soon to be the fate of the former. Where Sheridan is the presiding genius of the first two parts, Paine is now praised as ‘a real great man’. Fox is dismissed as ‘this time-serving leader of a self-interested faction’. The Society of the Friends of the People is attacked for speaking ‘the same puny enervating language’ and forming a ‘barrier between a corrupt government and the real friends of the people’.29 No doubt Grey’s club would have included Pigott among those it believed had ‘gone to excess on the subject of universal representation’.30

Whereas the first edition had opened its attack on the Duke of York by mocking the English for being ‘stupidly rooted in admiration of the glare and parade of royalty’, now the very institution of the monarchy is represented as irrelevant.31 Little deference is given even to the idea of an original unblemished British constitution. After a lengthy quotation from Junius in Part III, Pigott dissents from the earlier satirist’s ‘hyperbolical eulogium on the English constitution’.32 The French Convention is presented as the proper model of government:

Most of our celebrated English laws were framed in times of Gothic barbarism. The regenerated government of France will present itself to our admiration at the end of the 18th century, under the combined auspices of patriotism, experience, and philosophy.

Instead the absolute authority of the will of the people is insisted upon in the third and final part:

The sovereignty at present resides in the creator, the people, who have a natural interest in their own happiness and preservation; where as before it was lodged in the creature, the thing of their own creation, which as we have shown, had an interest directly contrary to, and subversive of them.

Pigott’s praise of Robespierre, Marat, and other ‘worthy gentlemen … members of the Jacobin Club’ brings him as close to being an ‘English Jacobin’ as anyone could be.33

Perhaps because it is not framed as a treatise on political principles as such, historians have tended to overlook the Jockey Club’s contribution to the Revolution controversy. Even politically sympathetic journals of the time, as we have seen, blanched at the personal content and indecent tone, but neither they nor the government ignored it. On 24 September 1792, the Prince of Wales wrote to Queen Charlotte in a state of high anxiety about the likely effects of Pigott’s work. He may have been writing out of a particular fear that the stories told about his circle were likely seriously to compromise his attempt to have his debts paid off by Parliament, but he was right to see that Pigott's pamphlet was not simply a scandal sheet. John Wilde believed it to be dangerously ubiquitous in Edinburgh: ‘I know not how it is received in London. Here it is rather a fashionable companion; and even in the lower and middling ranks of life you have as much chance to meet with it, as with a bible or an almanack.’34 The government took the same view, and may indeed have been keeping a watch on the pamphlet since the publication of Part II. The prince told the queen that it was ‘the most infamous & shocking libelous production yt. ever disgraced the pen of man’. She quickly forwarded it to the ministry.35 Henry Dundas immediately put the copy into the hands of the Attorney General. The Treasury Solicitor instructed magistrates to prosecute its publishers wherever they could, not just in London, but countrywide.36 Within a few weeks of the prince’s letter, prosecutions were underway against Ridgway and Symonds. Both were found guilty of sedition, forced to pay large fines, and confined in Newgate in 1793. Before the year was out, they had been joined there by their author, but not for publishing the Jockey Club.37

Prison and the LCS

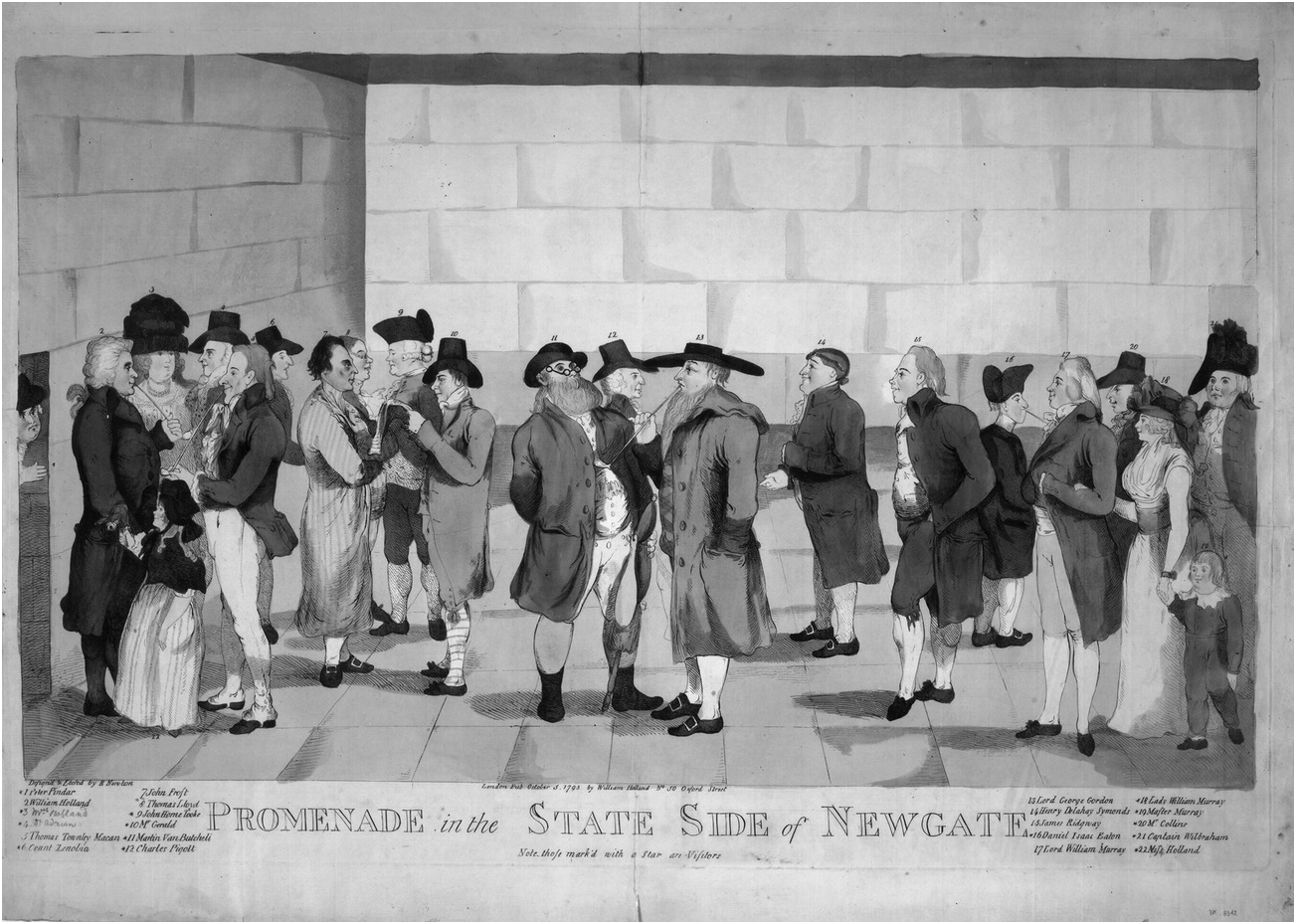

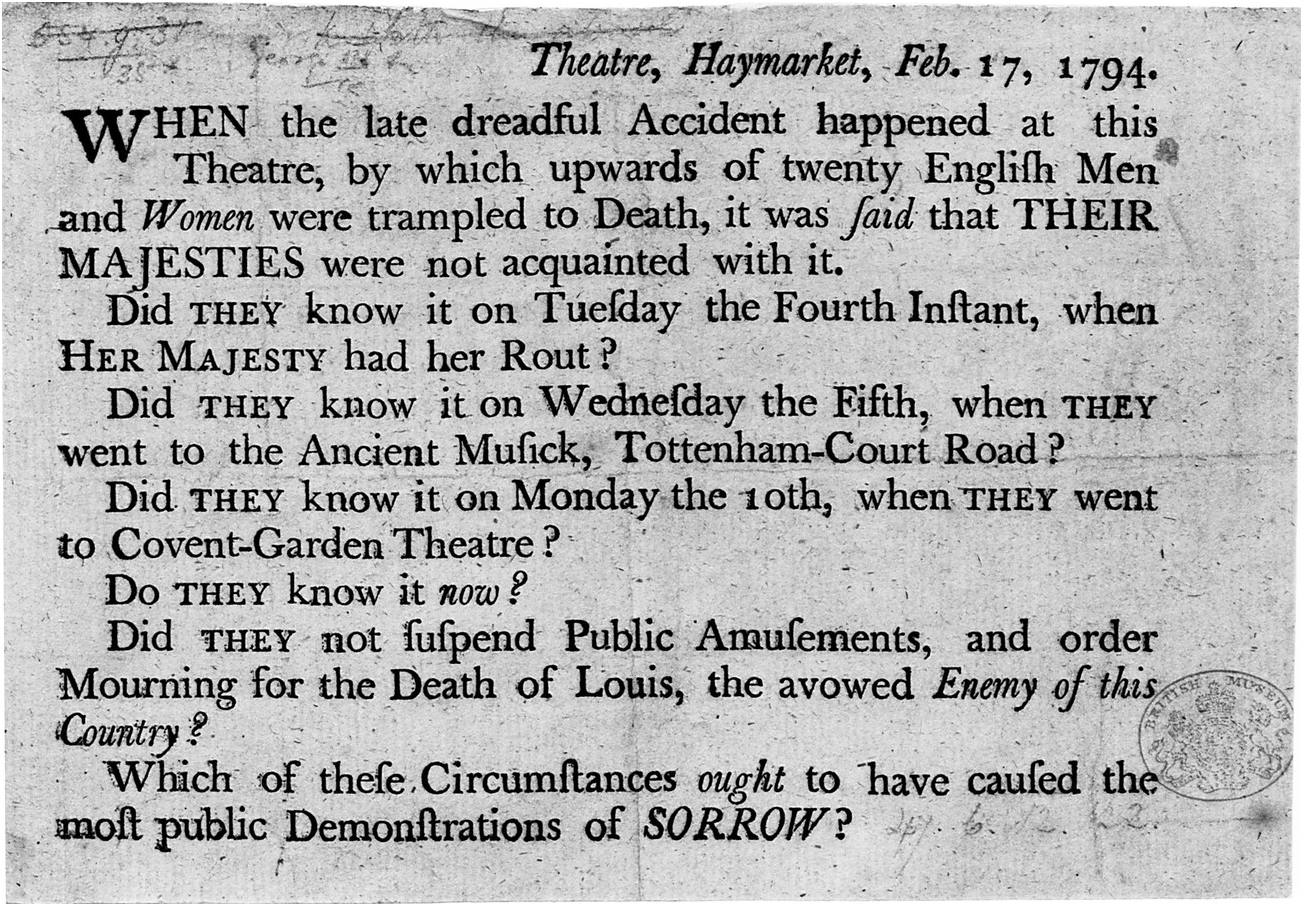

By the time Treachery no Crime was published early in August 1793, Pigott was closely involved with London’s radical circles. Godwin’s diary for 7 August 1793 records dining in John Frost’s room in Newgate with Pigott, Holcroft, Gerrald, Thomas Macan, and a ‘Macdonald’ who was probably D. E. MacDonnell.38 Pigott found a place in two of Richard Newton’s prints of the inmates and their visitors on the state side of the prison (Figures 6 and 7). Published on 20 August, Soulagement en Prison, or Comfort in Prison pictures the inmates and their visitors enjoying a convivial meal in Lord George Gordon’s rooms with various figures already mentioned several times in this book, including Frost, Gerrald, Ridgway, and Symonds.39 By the time Newton published Promenade on the State Side of Newgate in October 1793, Pigott was a prisoner there himself, awaiting trial. He was probably aware that the government would be watching his movements after the publication of the Jockey Club. To mitigate the charges against him, Ridgway had ‘authorized and directed his Attorney to give up the name of the Author of the Work’.40 In September 1793, presumably feeling the net closing in and short of funds, Pigott attempted to flee the country with Robert Merry, but they turned back at Harwich. Merry went into his exile in Scarborough, but Pigott returned to London, planning to reunite with Merry shortly, not least because his friend was now his main source of money.

Fig 6 Richard Newton, Soulagement en Prison, or Comfort in Prison. Lewis Walpole Library (1793).

Fig 7 Richard Newton, Promenade on the State Side of Newgate (1793).

On 30 September, Pigott was arrested after an incident at the New London coffee house involving the physician William Hodgson. The official indictment claimed that the two men began proposing republican toasts in their private box after a bout of drinking. The charge revolved around the accusation that Hodgson had denounced George III as a ‘German hog butcher’.41 The proprietor of the coffee house sent for the constables. Hodgson and Pigott were arraigned for uttering seditious words. Unluckily for Pigott, the duty magistrate was Mr Anderson, a target in Treachery no Crime.42 Anderson had Hodgson and Pigott committed to the New Compter gaol. Early in October, Pigott’s lawyer, John Martin, discovered mistakes in the warrant. Pigott also complained to the bench that the excessive amount of bail set contravened the Bill of Rights. A jury at the Old Bailey threw out the charges against Pigott on 2 November, but Hodgson was committed to Newgate, and eventually tried and found guilty in December.43

While in confinement, Pigott wrote his defence, later published as Persecution!!! His account of his evening with Hodgson was of two friends indulging ‘in that openness and freedom of discourse natural to persons, who harbour no criminal or secret intentions’. Hinting at an aspect of the defence Erskine had used in John Frost’s case, Pigott admitted they were ‘affected by liquor, when the temper is consequently more irritable than in moments of cooler reflections’.44 More generally, he staked his defence on Whig principles: ‘freedom of speech is an english man’s prerogative, engrafted on our Constitution, by magna charta and the bill of rights.’ When it came to issues of freedom of speech and the liberty of the press, as in the campaign against the Two Acts at the end of 1795, Foxite Whigs and the LCS could work together relatively closely using the same language of liberty. When pleading to a jury, it made sense to appeal to the shades of Russell and Sidney rather than natural rights, but Pigott’s defence does not always manage to hold to this line. Although he asserted that his republican principles were derived from perfectly constitutional notions of the ‘public good’, Persecution!!! went on to declare ‘that my fervent wishes shall be daily offered up for the success and final establishment of the french republic’. These were not words calculated to win an acquittal from an English jury had the case come to trial, but they should not simply be read as Pigott’s ‘real’ opinions emerging from beneath a tactical use of Whig vocabulary. They might better be seen as a snapshot in the process of Pigott rewriting his political lexicon in response to the fast-changing personal and political context, not least the need to save himself from gaol. Even in the ‘Preface’ to Persecution!!!, written after the charge had been thrown out, when he had no need to pander to the prejudices of a jury, Pigott fashions an idea of his sufferings against the backdrop of the pantheon of English liberty:

During the period of our history, when a Stuart reigned in England; when a Jefferies presided in the court of King’s Bench the source of justice was polluted, Judges were venal, and juries corrupt, Virtue and Crime were confounded; or rather Virtue was proscribed and punished; Crime rewarded and triumphant. A pander ennobled by the title of Duke of Buckingham, was the favourite of the prince. Jefferies, whose very name is synonymous with oppression and cruelty, was the protected Judge, under whose sentence and authority, a SIDNEY and a RUSSELL died on the scaffold.45

Thelwall’s lectures – when they started their new season in February – were full of this sort of appeal, but his relation to this tradition was rather different from Pigott’s.46 As a member of an old family, Pigott was not above asserting his independence as a gentleman over informers he represents as mere men of trade. It was not so easy to jettison patrician values as to take on the language of natural rights. Pigott loftily dismissed his two chief accusers – ‘this political pickle merchant’ and ‘formerly in the linen trade at Bristol’ – on the basis of their social inferiority. The language of gentlemanly independence would have been part of Pigott’s education at Eton and Cambridge and the common currency of his erstwhile friends in the Jockey Club when the talk turned from the turf to politics. As he insisted in his defence, ‘to declare my sentiments without reserve’ was ‘a habit in which I was bred, and which is rooted in me’. Anything else would be to cover English traditions of liberty with ‘our modern servility, transplanted’, as he put it with typical sarcasm, ‘from the old despotism of France’.47

On his release, Pigott appeared at meetings of the Philomath Society attended by William Godwin. Godwin’s diary for 14 January reads: ‘Tea at Holcroft’s: Philomathian supper; visitors Gerald & Pigot’.48 Gerrald at this stage was on bail. Eaton, who appears with Pigott in the October Newgate print, published Persecution!!! in December and announced at the end of March that he had copies of Strictures and Treachery no Crime available.49 Pigott became closely enough involved with popular radical circles to join the LCS (a path his friend Merry never took). February 1794 sees his name on a list of the members of division 25 on which Eaton and Thelwall also appear.50 Exactly when Pigott joined the LCS is not clear. He associated with members like Gerrald and Hodgson from at least mid-1793, but it may be that he only actually joined on his release from Newgate on 2 November. Certainly, there is desperation in the letter he wrote to Samuel Rogers a week later. The letter makes a disingenuous mention of the incident with Hodgson (‘the stupid accident with which I presume you have been made acquainted by the papers’). His financial situation had been worsened because events in France had cut him off from the ‘remittances’ he relied upon from his brother. Merry could not supply the loss:

It is only real want & a reluctance to apply to the Great World that could prevail on me to request a service of this nature from you, to whom I am unknown, but if you will be kind enough to advance me ten guineas, I think I may venture to aver with confidence that my Friend will make it good or otherwise, if you should have sufficient faith in me I have a French translation of the System of Nature in the Press which on being concluded a Bookseller has agreed to advance me 60L, when I should return the money, should Merry (which I think impossible) not have done so.51

The author of the System of Nature was the Baron d’Holbach, although editions of the time routinely attributed it to ‘Mirabaud’.52 The promotion of such texts in the LCS infuriated ‘saints’ like Bone and Lee. W. H. Reid later claimed that the System of Nature was ‘translated by a person confined in Newgate as a patriot, and published in weekly numbers, its sale was pushed, from the joint motive of serving the Author, and the cause in which the London Corresponding Society was engaged’.53 Intriguingly, an edition of the System of Nature was brought out by Pigott’s prison-mate William Hodgson in 1795–6 (embellished with engravings by Henry Richter). Hodgson is the most obvious candidate for Reid’s ‘person confined in Newgate,’ but he and Pigott may have worked together on a translation in prison.54 Pigott was obviously desperate to make money by selling books on his release. Apart from the mooted translation of Holbach, he seems to have drawn on his gaming past to edit New Hoyle, or the general repository of games, eventually published after his death by Ridgway in 1795, with rules for the fashionable card games of faro, cribbage, and rouge et noir added to the traditional compilation.55 More immediately, though, he seems to have looked to repeat the success of the Jockey Club, exploiting the general interest in the scandals of the aristocracy and even, in one instance, posing as a woman in print.

Scandalmonger and lexicographer

Margaret Coghlan had been born into a wealthy military family in 1762. She married the army officer John Coghlan during the American War, but her husband and then her father cast her off.56 Crossing the Atlantic, she embarked on a career as actress and courtesan, with lovers who included Fox and the Duke of York. She wrote a scandalous memoir naming many names, but reportedly died in London in 1787 before it could be published. The memoir finally appeared in January 1794, published by George Kearsley, ‘interspersed’, the title page informs us, ‘with anecdotes of the American and present French Wars, with remarks moral and political’. There was also a radical preface, extensive remarks on the moral laxity of the elite, and a second volume that celebrated ‘the glorious Epoch, the 14 of July, 1789, when Frenchmen threw off for ever, the yoke of slavery’.57 Throughout Coghlan’s Memoirs elite marital relations are represented as a form of tyranny in constraint of the natural affections, ‘an honourable prostitution’, as Coghlan describes it, that introduced her ‘to libertines, and to women of doubtful character’.58 The British Critic read the book, not very attentively, simply as a moral critique of ‘the licentiousness of elevated life’. Usually among the fiercest critics of radical opinion, the journal assumed Coghlan was still alive, and ‘now a prisoner for debt’, missing the appropriation of her voice to a radical critique. The author of the interspersions was Charles Pigott.59 Pigott’s amplifications of Coghlan’s memoirs returned to some favourite targets of the Jockey Club, including, for instance, General Dalrymple. Sarcastically described there as ‘equally distinguished for gallantry in love … as for bravery in war … this son of Mars, this favourite of Venus … equal to both and armed for either field’, he reappeared in the Memoirs as ‘this favourite of the fair sex, that renowned Warrior, equal to both and armed for either field’.60 Pigott often returned to the idea that the officer class was barely more effective – if busier – in the bedroom than on the battlefield. Their commander-in-chief the Duke of York was a favourite target. Pigott had reportedly been discussing the duke’s character with Hodgson just prior to their arrest.61 Coghlan’s Memoirs drily comments on the duke: ‘if this princely Lothario shines not with greater advantage in the plains of Mars than he excels in the groves of Venus, the combined forces have little to expect from his martial exertions.’62 On 10 February 1794, The Times noted that

the publication of Mrs. Coghlan’s Memoirs just on the eve of a Royal Duke [of York]’s return, will not prove very acceptable to him; anecdotes there are of a singular nature; nor should we wonder if on that account they were to be suppressed.

The duke soon had even more to annoy him when Eaton published Pigott’s the Female Jockey Club on 8 March.63 In an arch piece of self-promotion, Coghlan appears in its cast on the basis of her ‘literary merit’. ‘If her soul really breath the sentiments contained in the memoirs,’ wrote Pigott praising his own amplifications, then ‘she possesses titles far superior to any, which all the kings in the world have it in their power to bestow.’64 ‘This author’, claimed Erskine,

libelled all those who were entrusted with the Government of the Country, and all those, whoever they were, who were placed in the most respectable situations [in the Jockey Club]; and after having exhausted that sex, he then fastened on the weaker sex, (whom all agreed to protect) beginning with the wife of the Sovereign, [and] the royal princesses.65

There are plenty of examples to choose from. Pigott claimed, for instance, that Lady Archer was as ‘adept in certain manual exercises’, including ‘raising a cock at faro’.66 Condemning aristocratic women for publicly displaying themselves at routs and gaming tables was becoming a familiar part of the growing moralism of public culture, but Pigott’s heady cocktail was far from usual. Throughout the main culprit in terms of public display – the reader is reminded from the Jockey Club – are ‘the stupid barbarous prejudices of Royalty’.67

The Female Jockey Club opposes an enlightenment celebration of natural energies to aristocratic artifice in a way that echoes Holbach’s materialism. Libertine punning often shares the page with a critique of ‘superficial delicacies and luxuries’ opposed to ‘those heavenly enjoyments, which Nature has indulgently yielded, to make the bitter draught of life go down’. The opening entry in the Female Jockey Club condemns the enslavement of the royal princesses to ‘the sterile solitude of celibacy’, reading the royal household in terms of the paternal tyranny regularly attacked in sentimental fiction and the Gothic novel, not to mention much of Robert Merry’s writing. ‘Nature will prevail’, as Pigott puts it in his discussion of the princesses, becomes an over-determined motto as sentimental moralism meets libertine insinuation.68 The collection ran into several editions, including a fourth edition of five thousand copies Eaton claimed, but the publisher did not escape trouble.69 Lady Elizabeth Luttrell brought a libel case against the book for a passage claiming she received ‘select visitors in her private apartments’. There, Pigott claimed, she ‘employed to make herself agreeable … forget her age, and act again the joys of voluptuous youth’.70 A lengthy report of the trial appeared in The Times on 31 July. Erskine, appearing for the prosecution, described Pigott’s book as a ‘supplement to another work of malice [The Jockey Club], which had for its object to libel everything that was virtuous, honourable, and respectable in this country’. Erskine’s role is an indication, if one is needed, of just how far Pigott had become alienated from his old Whig networks. Eaton was found guilty at the end of July, but settled out of court.71 Pigott was beyond such mercies, as several newspapers noticed. He had died in his apartments on Tottenham Court Road at the end of June. John Gurney, Eaton’s lawyer, described him as ‘possessing the ablest head, with the blackest heart … gone to answer for this and all other offences at a higher Tribunal’.72

The gaol fever that had killed many others held in Newgate probably killed Pigott. His body was interred in his family vault in Chetwynd, but his legacy was not so easily claimed by the proprieties of the landed gentry. After his death, Eaton brought out a posthumous copy of his Political Dictionary (1795).73 There are fewer better illustrations of John Barrell’s claim that political struggle in the 1790s was often about the meaning of words.74 In the Political Dictionary, the vocabulary of customary rights and traditional liberties that conditioned most eighteenth-century political discourse is presented as a smoke screen designed to exclude the people from political participation. The attachment to constitutional monarchy is defined in terms of a Whig preference for closed networks of ‘influence’ over democratic transparency:

Whig, - a person who prefers the influence of House of Hanover to the prerogative of the Stuarts. I am an enemy to both; but if we must languish under one or the other, I would, without hesitation, prefer the prerogative of the Stuarts, and for this reason – where prerogative is, the defence and justification of an arbitrary act, all the odium which such an act would, is attached to the king himself; whereas, when this same arbitrary act is induced, through the medium of influence, the odium rests on no one in particular.

Every part of the church and state is subjected to pithy evaluation and dismissal.

The Opposition fares little better than the Ministry. The entry under so innocuous seeming a word as ‘Fulsome’ gives a sense of Pigott’s disdain for the manners of the great. The image of Fox as the ‘Man of the People,’ a target of Pigott’s from at least 1785, is reduced to a public show masking private vice:

Charles Fox eternally passing compliments in his parliamentary speeches on the infamous B-ke. The manner in which members of both Houses of Parliament address each other. Noble Duke, Noble Lord, Right Honorable Gentleman, Learned Friend &c &c &c. This language may very properly be styled fulsome, since it is generally applied to the most unfeeling and corrupt beings of the human race.75