Few people denied Robert Merry’s charm. Years after his death, John Bernard still celebrated him from among all those who gathered at the Beefsteak Club, Fox and Sheridan included, as the one with the most ‘benevolent mould of mind’.1 This reputation underwrote Merry’s political credentials for many sympathisers, confirming that his character was grounded in right feeling. For others, as we have seen, his political enthusiasm warped and, ultimately, betrayed his sociable nature. Hardly anyone ever made either claim for Charles ‘Louse’ Pigott, despite the fact that he and Merry were friends from similar backgrounds. Pigott had a lasting image as a man who had ‘robbed his friends, cheated his creditors, repudiated his wife, and libelled all his acquaintance’.2 Nevertheless, he made two of the most influential contributions to the popular radical literature of the 1790s. The anonymous The Jockey Club (1792) rivalled Rights of Man, at least in the alarm it spread among the government’s law officers. His posthumous Political Dictionary (1795) was endlessly recycled in the contest over the legitimacy of the traditional language of politics. Both books made great play with the politics of personality without making much of Pigott’s own. He did publish some things under his own name, but never created a print personality after the manner of Merry. ‘Louse’ was the derisive nickname known to the relatively closed circle who shared his elite background. Generally, he proved as adaptive as the insect he was named after, thriving in the crevices of print culture, mixing political theory and French materialism with scandal and blackmail, unevenly espousing a radical politics while continuing to insist on his independence as a gentleman, until the government caught up with him and gaol fever killed him.

Cracking the louse

Pigott was the youngest son of an old Jacobite family whose family seat was the manor of Chetwynd Park, Shropshire.3 His eldest brother Robert was a member of the exclusive Jockey Club, who became High Sheriff of the county in 1774, but two years later sold the family estates and moved to the continent. Robert played a direct role in the political clubs of Paris during some of the headiest days of the Revolution before settling in Toulouse in 1792 (dying there in 1794). Probably an important conduit of French ideas to Charles, his remittances also bankrolled his younger brother, at least until politics in France blocked this supply line. Charles went to Eton and in 1769 matriculated at Trinity Hall Cambridge. Soon afterwards he lost a fortune on the turf, mixing in high-rolling Foxite circles. His friends, Fox among them, apparently subscribed to help him out of debtor’s prison. Nevertheless, Pigott felt free to attack Fox’s pose as ‘Man of the People’. In the first of two letters that appeared in the Public Advertiser in March 1785, he berated Fox for stooping to exploit every ruse available in the unreformed electoral system. Their tone confirmed Pigott’s own status as a gentleman of independent mind even as it mourned Fox’s manipulation of the mob:

In committing my thoughts to the public, I am instigated by no other motives, than, I fear, a vain desire of convincing them of their error, and of lamenting those fatal prejudices in many great and exalted characters which have induced them to display such indecent exultation upon a triumph wherein every sensible dispassionate person, who was an ocular witness to the infamous disgraceful proceedings of the Westminster Election, must be affected with the deepest sorrow and indignation.

The second on Fox’s position on Irish affairs hints at Pigott’s adaptive response to print:

Newspapers are the great extensive vehicles of general intelligence; and as the Public Advertiser is universally read, I have selected that publication as best adapted to my purpose.4

Fox and his friends were ambivalent about newspapers as places to argue out political principles, but they were far from slow to respond to Pigott on the field of satire.5 Between the two letters, the Morning Herald – a vociferous supporter of Fox – published four epigrams, headed ‘Reason for Mr. Fox’s avowed contempt for one pigot’s Address to him’, all playing on the idea of the louse as an inhabitant of a vermin-infested (debtor’s) prison:

Despite these slap downs, an antipathy to the hypocrisy of Fox’s pose as ‘Man of the People’ was to remain a more or less consistent part of Pigott’s rhetoric as he made an uneven and incomplete journey from the elite language of independence to the natural rights arguments associated with Thomas Paine and the French Revolution.

Robert Pigott had published in English on French affairs in the 1780s, including New Information and Lights, on the Late Commercial Treaty (1787), which the Critical Review dismissed as ‘the refuse of political rancour, poured forth with petulance, and in language that violates the plainest rules of English grammar’. In the early stages of the Revolution, he addressed the National Assembly in another pamphlet, also published in English, on the liberty of the press.7 Charles made his first intervention in the British ‘debate’ over the French Revolution in Strictures on the New Political Tenets of the Right Honourable Edmund Burke (1791). Published by Ridgway, it was designed as an answer to Burke’s Appeal from the New to the Old Whigs (1791) and Letter to a Member of the National Assembly (1791). The pamphlet initially presents itself as an attack on Burke’s defection from ‘every idea of friendship and party attachment’, but shows some sensitivity to Pigott’s own vulnerability in this score, given his newspaper letters to Fox. Those attacks, Pigott implied, had been based on policies not persons, but went on to suggest – in relation to the account of Burke – that ‘every trader in politics should be scouted’.8 His most influential contributions to the popular radical cause from 1792 were all to develop just such an unstable mixture of personal muckraking and republican principles for an increasingly popular audience.

Pigott’s representation of Burke as a ‘deserter from an honourable cause’ proposed that ‘the principles that provoked and justified American resistance, are exactly similar with those that brought about the French revolution’. Burke was reneging on a conception of inalienable popular sovereignty that he had defended in the case of the American revolutionaries. These differences might be construed as an in-house dispute about the meaning of the Whig tradition, not least because Burke is represented as deserting the social network associated with Fox, except that as Strictures progresses a different kind of language emerges. Expanding upon the hints in his earlier letters to the Public Advertiser, Pigott dismisses the distinction between Whig and Tory as illusory: ‘From the instant either one or other approach the throne in a ministerial capacity, they must, like camelions, change their natural colour.’9 Even these opinions might be seen as an assertion of pure Whig values, Pigott represents the National Assembly as primarily concerned with the ‘correction of abuses’, but towards its close Strictures starts to invoke Rousseau’s notions of the general will.10 Thomas Paine is lauded as ‘the distinguished and successful rival of Mr. Burke’. The language of traditional rights is to be abandoned in favour of ‘the lights of reason and truth … and … that theory, whose basis is fixed on the natural and untransferable rights of Men and Citizens’.11

Given the French connections he had through his brother, the appearance of this kind of language in Strictures is hardly surprising. Even so, while ‘the natural and untransferable rights of man’ may dominate the later parts of Strictures, it would be misleading to suggest that it entirely effaces the vocabulary of English liberty. Even his later pamphlet Treachery no Crime (1793) is still loath to abandon the idea of the excellence of the original constitution despite the ‘polypuses and rotten excrescencies that have grown upon it’.12 What does newly appear there is the influence of Political Justice, which it quotes regularly, for instance in representing utility – ‘the comparative benefits or injuries which it yields’ – as the best gauge of a constitution. Far less reminiscent of Godwin are the personal attacks in Treachery no Crime on the ‘lazy effeminacy and luxury of courts’.13 Where for the most part Strictures reads as a discussion of political principles, underwritten by the author’s name, Treachery no Crime (1793) – with ‘all the signs of hasty composition’, as the Analytical complained – is full of scurrilous barbs, but it looks like a pale shadow of the Jockey Club, the pamphlet that Pigott had brought out over the course of the previous year. Both were published anonymously, unlike Strictures. If ‘debate’ seems a poor description for the guerilla war being conducted in print over the French Revolution by the end of 1792, then Pigott and the Jockey Club played a major part in the transformation from disquisitions on principles to a fight – with the gloves off – over the legitimacy of the ruling classes.

Riding the aristocracy

Pigott had given notice of a willingness to bring the political elite – of whatever party – to the court of the popular press in 1785. The promise was more than made good in the Jockey Club, published in three parts as it expanded over the course of 1792. Strictures insisted that the author still preserved ‘the utmost respect for the personal and political character of Mr. Fox’.14 The personal affiliations of elite politics survive reasonably intact there, not least because Burke is chastised for reneging on them, but in the Jockey Club, or A Sketch of the Manners of the Age (1792) personal knowledge of the Whig oligarchy as well as the Crown and its allies was used with devastating effect to present the ruling elite as morally bankrupt. Taking the form of a series of brief and deeply scurrilous potted biographies, starting with the Prince of Wales, but moving on to his Whig connections, the Jockey Club proposed to show ‘that a revolution in government, can alone bring about a revolution in morals; while it continues the custom to annex such servile awe and prostituted reverence to those who are virtually the most undeserving of it’.15

Unaware of Pigott’s identity, John Wilde, Professor of Civil Law at Edinburgh University, saw the pamphlet as following an example learnt from the French:

The present state of France is, in no small degree, owing to the calumnies circulated against the higher orders, and especially the criminalities forged against the Court. The same game is playing in this country. No instrument employed in it can be contemptible. Vice certainly ought to be justified no where; among the higher ranks perhaps less than anywhere. But he is blind, indeed, who does not see why real vices are exaggerated against them in this age, and others pretended that do not exist. And that man has, in truth, little foresight who does not see the consequence of such publications being much read and believed.16

Wilde’s assumption was not unreasonable. Pigott had defined his aim as taking ‘the dust out of the eyes of the multitude, in lessening that aristocratic influence which so much pains are now taking to perpetuate’.17 Be that as it may, the patriot idea of a moral crusade in the name of reform in the preface is scarcely preparation for the coruscating and often indecent satire of the sketches themselves. One of the earliest attacks on the Jockey Club, the British Constitution Invulnerable (1792) identified a division of labour between Paine and Pigott: Paine engaged with principles, the author claimed, where Pigott used his personal knowledge of the political elite to attack their persons. An Answer to Three Scurrilous Pamphlets (1792), seemingly written by someone from within or familiar with Pigott’s old gambling circles, provided a much fiercer rebuttal. Using Pigott’s own satirical tactics, personal knowledge of his past is flourished to claim that he had robbed his friends and repudiated his wife. The author chronicles Pigott’s education at Eton, where he was started to be known as ‘Louse’; his political disaffection is represented as the result of an unhappy fashionable marriage and gambling debts; his ingratitude to Fox is framed via an anecdote about the subscription to release him from debtor’s prison. An Answer also claims some paragraphs had first been offered to his victims as blackmail threats: ‘Copies of these libels he has occasionally sent to several ladies; some of whom have deprecated his menaces, with presents of Bank paper.’18

Certainly Pigott was a master of insinuation and titillation. Many who sympathised with the Jockey Club’s politics could not accept its method. Reviewing a fourth edition of Part I in May 1792, the Analytical Review could approve of the political sentiments, but judged much of its content ‘too personal for us to attempt to accompany the author in his biographical sketches’.19 With no sympathy for Pigott’s politics, the author of the British Constitution Invulnerable was much blunter: ‘gross ideas are concealed under equivocal expressions and indecent subjects amplified’.20 Colonel George Hanger was already a staple figure of newspaper gossip and satirical prints.21 The fact that he had been Fox’s agent at the Westminster election of 1784 made him irresistible for Pigott’s amplifications. The description starts relatively mildly: ‘The person in question is admirably calculated to have shone a conspicuous figure in courts, when it was the custom to keep a f—l.’ Typically insults turn to accounts of sexual peccadillos in the Jockey Club. Hanger was no exception:

The M-j-r has of late connected himself with a lady of very amiable accomplishments; – none of your flimsy, delicate beauties; she is composed of true substantial English materials, and what there is plenty of her, cut and come again.22

Many of the entries show a libertine delight in obscene punning that was a familiar part of the masculine ethos of aristocratic clubs. The description of General William Dalrymple, for instance, notes that he had married ‘a young lady who had been much celebrated for the admirable dexterity of certain manual operations, still remembered with a kind of pleasing melancholy by several gentlemen now living’.23

Many of the stories had already appeared in newspaper paragraphs. Wilde assumed that the pamphlet had been ‘pilfered almost entirely from magazines and former scandalous chronicles of the times’.24 Pigott was supplying a ‘daily insinuation’ to the press before he gathered the paragraphs into his book. ‘Characters from the Jockey Club’ appear in the Bon Ton Magazine early in 1792, probably to extort money from their targets. Certainly, Ridgway, one of The Jockey Club’s publishers, had been using this kind of technique for a while.25 Material that later surfaced in the Jockey Club’s paragraphs on Charles James Fox appear without acknowledgement in the April issue of the Bon Ton, but nothing from the two later parts of the Jockey Club, where the affiliation to Painite politics is much clearer. Events in France were regularly featured in the Bon Ton’s pages, but only as warning tales of the violent excesses of the crowd.26 Stories of aristocratic debauchery could be a source of amusement in the Bon Ton Magazine, but when they were hitched to a republican political programme, then it was another matter.

The first part of the Jockey Club, published at the end of February, was relatively mild on Fox and the Whig party. The Prince of Wales is execrated as an example of how ‘disgraceful it is to pay homage to a person merely on account of his descent’, but the possibility that Fox and, especially, Sheridan might live up to their reputations as friends of liberty is kept alive. At this stage still professing an attachment to ‘limited monarchy’, Pigott calls upon Fox to rouse himself, live up to his initial welcome for the French Revolution, and exert himself against the encroachments of the Crown. Pigott sees Sheridan as the more principled of the two politicians. If he lives up to his reputation, ‘he will be adored while living, and his name enrolled on the register of immortality, amongst the most distinguished patriots and benefactors of mankind’.27 The superiority of Sheridan over Fox is more pronounced in the second part, published in May, where he appears as the only politician ‘whose public principles stand unimpeached’. Fox is castigated for his deference to ‘aristocratic connections’.28 The third part written after the events of 10 August and the September massacres in Paris, published on 15 September, is openly republican, beginning, to the astonishment of the Analytical Review, with a deeply unflattering comparison of George III and Louis XVI that implied that the deposition of the latter in August would and ought soon to be the fate of the former. Where Sheridan is the presiding genius of the first two parts, Paine is now praised as ‘a real great man’. Fox is dismissed as ‘this time-serving leader of a self-interested faction’. The Society of the Friends of the People is attacked for speaking ‘the same puny enervating language’ and forming a ‘barrier between a corrupt government and the real friends of the people’.29 No doubt Grey’s club would have included Pigott among those it believed had ‘gone to excess on the subject of universal representation’.30

Whereas the first edition had opened its attack on the Duke of York by mocking the English for being ‘stupidly rooted in admiration of the glare and parade of royalty’, now the very institution of the monarchy is represented as irrelevant.31 Little deference is given even to the idea of an original unblemished British constitution. After a lengthy quotation from Junius in Part III, Pigott dissents from the earlier satirist’s ‘hyperbolical eulogium on the English constitution’.32 The French Convention is presented as the proper model of government:

Most of our celebrated English laws were framed in times of Gothic barbarism. The regenerated government of France will present itself to our admiration at the end of the 18th century, under the combined auspices of patriotism, experience, and philosophy.

Instead the absolute authority of the will of the people is insisted upon in the third and final part:

The sovereignty at present resides in the creator, the people, who have a natural interest in their own happiness and preservation; where as before it was lodged in the creature, the thing of their own creation, which as we have shown, had an interest directly contrary to, and subversive of them.

Pigott’s praise of Robespierre, Marat, and other ‘worthy gentlemen … members of the Jacobin Club’ brings him as close to being an ‘English Jacobin’ as anyone could be.33

Perhaps because it is not framed as a treatise on political principles as such, historians have tended to overlook the Jockey Club’s contribution to the Revolution controversy. Even politically sympathetic journals of the time, as we have seen, blanched at the personal content and indecent tone, but neither they nor the government ignored it. On 24 September 1792, the Prince of Wales wrote to Queen Charlotte in a state of high anxiety about the likely effects of Pigott’s work. He may have been writing out of a particular fear that the stories told about his circle were likely seriously to compromise his attempt to have his debts paid off by Parliament, but he was right to see that Pigott's pamphlet was not simply a scandal sheet. John Wilde believed it to be dangerously ubiquitous in Edinburgh: ‘I know not how it is received in London. Here it is rather a fashionable companion; and even in the lower and middling ranks of life you have as much chance to meet with it, as with a bible or an almanack.’34 The government took the same view, and may indeed have been keeping a watch on the pamphlet since the publication of Part II. The prince told the queen that it was ‘the most infamous & shocking libelous production yt. ever disgraced the pen of man’. She quickly forwarded it to the ministry.35 Henry Dundas immediately put the copy into the hands of the Attorney General. The Treasury Solicitor instructed magistrates to prosecute its publishers wherever they could, not just in London, but countrywide.36 Within a few weeks of the prince’s letter, prosecutions were underway against Ridgway and Symonds. Both were found guilty of sedition, forced to pay large fines, and confined in Newgate in 1793. Before the year was out, they had been joined there by their author, but not for publishing the Jockey Club.37

Prison and the LCS

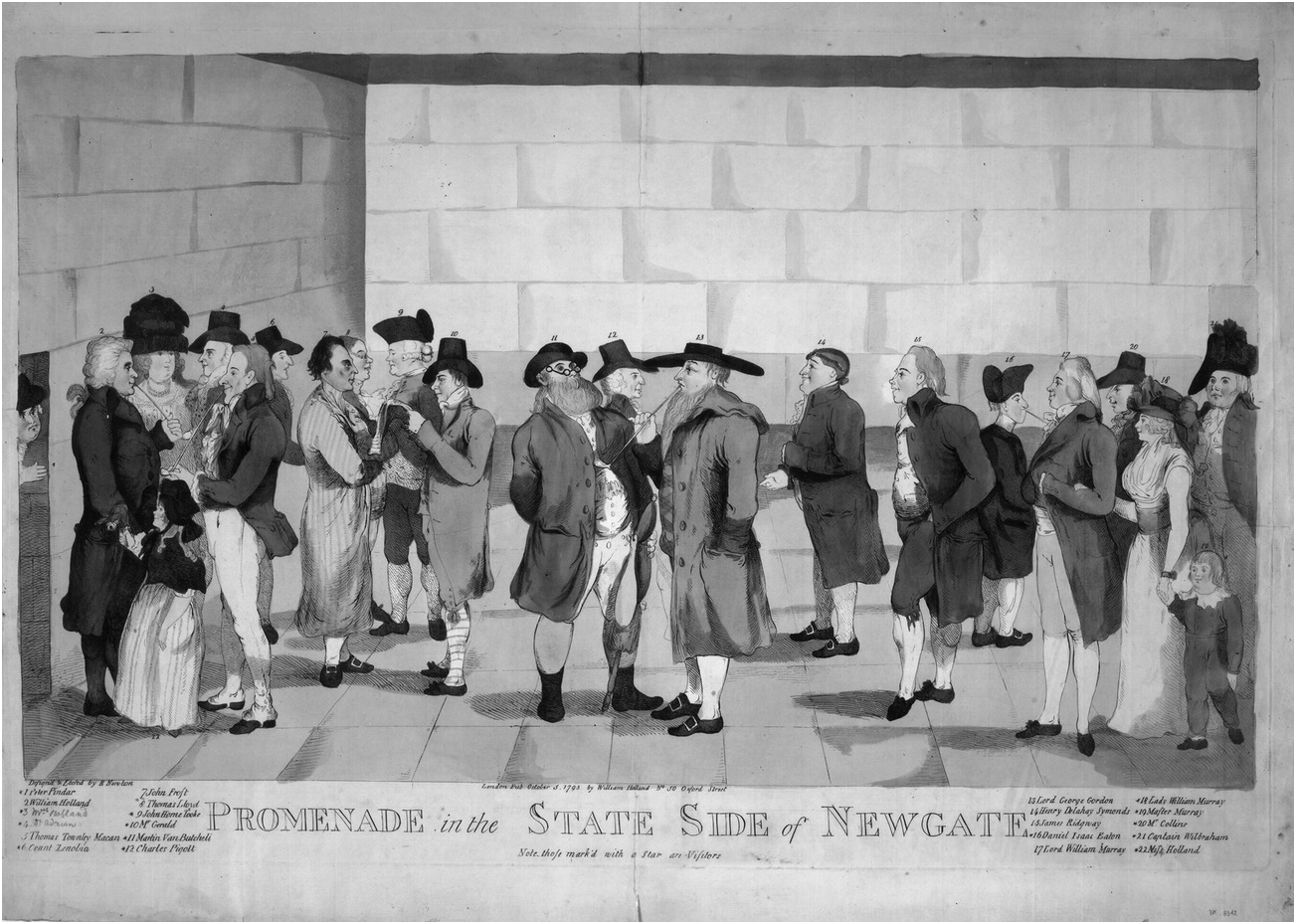

By the time Treachery no Crime was published early in August 1793, Pigott was closely involved with London’s radical circles. Godwin’s diary for 7 August 1793 records dining in John Frost’s room in Newgate with Pigott, Holcroft, Gerrald, Thomas Macan, and a ‘Macdonald’ who was probably D. E. MacDonnell.38 Pigott found a place in two of Richard Newton’s prints of the inmates and their visitors on the state side of the prison (Figures 6 and 7). Published on 20 August, Soulagement en Prison, or Comfort in Prison pictures the inmates and their visitors enjoying a convivial meal in Lord George Gordon’s rooms with various figures already mentioned several times in this book, including Frost, Gerrald, Ridgway, and Symonds.39 By the time Newton published Promenade on the State Side of Newgate in October 1793, Pigott was a prisoner there himself, awaiting trial. He was probably aware that the government would be watching his movements after the publication of the Jockey Club. To mitigate the charges against him, Ridgway had ‘authorized and directed his Attorney to give up the name of the Author of the Work’.40 In September 1793, presumably feeling the net closing in and short of funds, Pigott attempted to flee the country with Robert Merry, but they turned back at Harwich. Merry went into his exile in Scarborough, but Pigott returned to London, planning to reunite with Merry shortly, not least because his friend was now his main source of money.

Fig 6 Richard Newton, Soulagement en Prison, or Comfort in Prison. Lewis Walpole Library (1793).

Fig 7 Richard Newton, Promenade on the State Side of Newgate (1793).

On 30 September, Pigott was arrested after an incident at the New London coffee house involving the physician William Hodgson. The official indictment claimed that the two men began proposing republican toasts in their private box after a bout of drinking. The charge revolved around the accusation that Hodgson had denounced George III as a ‘German hog butcher’.41 The proprietor of the coffee house sent for the constables. Hodgson and Pigott were arraigned for uttering seditious words. Unluckily for Pigott, the duty magistrate was Mr Anderson, a target in Treachery no Crime.42 Anderson had Hodgson and Pigott committed to the New Compter gaol. Early in October, Pigott’s lawyer, John Martin, discovered mistakes in the warrant. Pigott also complained to the bench that the excessive amount of bail set contravened the Bill of Rights. A jury at the Old Bailey threw out the charges against Pigott on 2 November, but Hodgson was committed to Newgate, and eventually tried and found guilty in December.43

While in confinement, Pigott wrote his defence, later published as Persecution!!! His account of his evening with Hodgson was of two friends indulging ‘in that openness and freedom of discourse natural to persons, who harbour no criminal or secret intentions’. Hinting at an aspect of the defence Erskine had used in John Frost’s case, Pigott admitted they were ‘affected by liquor, when the temper is consequently more irritable than in moments of cooler reflections’.44 More generally, he staked his defence on Whig principles: ‘freedom of speech is an english man’s prerogative, engrafted on our Constitution, by magna charta and the bill of rights.’ When it came to issues of freedom of speech and the liberty of the press, as in the campaign against the Two Acts at the end of 1795, Foxite Whigs and the LCS could work together relatively closely using the same language of liberty. When pleading to a jury, it made sense to appeal to the shades of Russell and Sidney rather than natural rights, but Pigott’s defence does not always manage to hold to this line. Although he asserted that his republican principles were derived from perfectly constitutional notions of the ‘public good’, Persecution!!! went on to declare ‘that my fervent wishes shall be daily offered up for the success and final establishment of the french republic’. These were not words calculated to win an acquittal from an English jury had the case come to trial, but they should not simply be read as Pigott’s ‘real’ opinions emerging from beneath a tactical use of Whig vocabulary. They might better be seen as a snapshot in the process of Pigott rewriting his political lexicon in response to the fast-changing personal and political context, not least the need to save himself from gaol. Even in the ‘Preface’ to Persecution!!!, written after the charge had been thrown out, when he had no need to pander to the prejudices of a jury, Pigott fashions an idea of his sufferings against the backdrop of the pantheon of English liberty:

During the period of our history, when a Stuart reigned in England; when a Jefferies presided in the court of King’s Bench the source of justice was polluted, Judges were venal, and juries corrupt, Virtue and Crime were confounded; or rather Virtue was proscribed and punished; Crime rewarded and triumphant. A pander ennobled by the title of Duke of Buckingham, was the favourite of the prince. Jefferies, whose very name is synonymous with oppression and cruelty, was the protected Judge, under whose sentence and authority, a SIDNEY and a RUSSELL died on the scaffold.45

Thelwall’s lectures – when they started their new season in February – were full of this sort of appeal, but his relation to this tradition was rather different from Pigott’s.46 As a member of an old family, Pigott was not above asserting his independence as a gentleman over informers he represents as mere men of trade. It was not so easy to jettison patrician values as to take on the language of natural rights. Pigott loftily dismissed his two chief accusers – ‘this political pickle merchant’ and ‘formerly in the linen trade at Bristol’ – on the basis of their social inferiority. The language of gentlemanly independence would have been part of Pigott’s education at Eton and Cambridge and the common currency of his erstwhile friends in the Jockey Club when the talk turned from the turf to politics. As he insisted in his defence, ‘to declare my sentiments without reserve’ was ‘a habit in which I was bred, and which is rooted in me’. Anything else would be to cover English traditions of liberty with ‘our modern servility, transplanted’, as he put it with typical sarcasm, ‘from the old despotism of France’.47

On his release, Pigott appeared at meetings of the Philomath Society attended by William Godwin. Godwin’s diary for 14 January reads: ‘Tea at Holcroft’s: Philomathian supper; visitors Gerald & Pigot’.48 Gerrald at this stage was on bail. Eaton, who appears with Pigott in the October Newgate print, published Persecution!!! in December and announced at the end of March that he had copies of Strictures and Treachery no Crime available.49 Pigott became closely enough involved with popular radical circles to join the LCS (a path his friend Merry never took). February 1794 sees his name on a list of the members of division 25 on which Eaton and Thelwall also appear.50 Exactly when Pigott joined the LCS is not clear. He associated with members like Gerrald and Hodgson from at least mid-1793, but it may be that he only actually joined on his release from Newgate on 2 November. Certainly, there is desperation in the letter he wrote to Samuel Rogers a week later. The letter makes a disingenuous mention of the incident with Hodgson (‘the stupid accident with which I presume you have been made acquainted by the papers’). His financial situation had been worsened because events in France had cut him off from the ‘remittances’ he relied upon from his brother. Merry could not supply the loss:

It is only real want & a reluctance to apply to the Great World that could prevail on me to request a service of this nature from you, to whom I am unknown, but if you will be kind enough to advance me ten guineas, I think I may venture to aver with confidence that my Friend will make it good or otherwise, if you should have sufficient faith in me I have a French translation of the System of Nature in the Press which on being concluded a Bookseller has agreed to advance me 60L, when I should return the money, should Merry (which I think impossible) not have done so.51

The author of the System of Nature was the Baron d’Holbach, although editions of the time routinely attributed it to ‘Mirabaud’.52 The promotion of such texts in the LCS infuriated ‘saints’ like Bone and Lee. W. H. Reid later claimed that the System of Nature was ‘translated by a person confined in Newgate as a patriot, and published in weekly numbers, its sale was pushed, from the joint motive of serving the Author, and the cause in which the London Corresponding Society was engaged’.53 Intriguingly, an edition of the System of Nature was brought out by Pigott’s prison-mate William Hodgson in 1795–6 (embellished with engravings by Henry Richter). Hodgson is the most obvious candidate for Reid’s ‘person confined in Newgate,’ but he and Pigott may have worked together on a translation in prison.54 Pigott was obviously desperate to make money by selling books on his release. Apart from the mooted translation of Holbach, he seems to have drawn on his gaming past to edit New Hoyle, or the general repository of games, eventually published after his death by Ridgway in 1795, with rules for the fashionable card games of faro, cribbage, and rouge et noir added to the traditional compilation.55 More immediately, though, he seems to have looked to repeat the success of the Jockey Club, exploiting the general interest in the scandals of the aristocracy and even, in one instance, posing as a woman in print.

Scandalmonger and lexicographer

Margaret Coghlan had been born into a wealthy military family in 1762. She married the army officer John Coghlan during the American War, but her husband and then her father cast her off.56 Crossing the Atlantic, she embarked on a career as actress and courtesan, with lovers who included Fox and the Duke of York. She wrote a scandalous memoir naming many names, but reportedly died in London in 1787 before it could be published. The memoir finally appeared in January 1794, published by George Kearsley, ‘interspersed’, the title page informs us, ‘with anecdotes of the American and present French Wars, with remarks moral and political’. There was also a radical preface, extensive remarks on the moral laxity of the elite, and a second volume that celebrated ‘the glorious Epoch, the 14 of July, 1789, when Frenchmen threw off for ever, the yoke of slavery’.57 Throughout Coghlan’s Memoirs elite marital relations are represented as a form of tyranny in constraint of the natural affections, ‘an honourable prostitution’, as Coghlan describes it, that introduced her ‘to libertines, and to women of doubtful character’.58 The British Critic read the book, not very attentively, simply as a moral critique of ‘the licentiousness of elevated life’. Usually among the fiercest critics of radical opinion, the journal assumed Coghlan was still alive, and ‘now a prisoner for debt’, missing the appropriation of her voice to a radical critique. The author of the interspersions was Charles Pigott.59 Pigott’s amplifications of Coghlan’s memoirs returned to some favourite targets of the Jockey Club, including, for instance, General Dalrymple. Sarcastically described there as ‘equally distinguished for gallantry in love … as for bravery in war … this son of Mars, this favourite of Venus … equal to both and armed for either field’, he reappeared in the Memoirs as ‘this favourite of the fair sex, that renowned Warrior, equal to both and armed for either field’.60 Pigott often returned to the idea that the officer class was barely more effective – if busier – in the bedroom than on the battlefield. Their commander-in-chief the Duke of York was a favourite target. Pigott had reportedly been discussing the duke’s character with Hodgson just prior to their arrest.61 Coghlan’s Memoirs drily comments on the duke: ‘if this princely Lothario shines not with greater advantage in the plains of Mars than he excels in the groves of Venus, the combined forces have little to expect from his martial exertions.’62 On 10 February 1794, The Times noted that

the publication of Mrs. Coghlan’s Memoirs just on the eve of a Royal Duke [of York]’s return, will not prove very acceptable to him; anecdotes there are of a singular nature; nor should we wonder if on that account they were to be suppressed.

The duke soon had even more to annoy him when Eaton published Pigott’s the Female Jockey Club on 8 March.63 In an arch piece of self-promotion, Coghlan appears in its cast on the basis of her ‘literary merit’. ‘If her soul really breath the sentiments contained in the memoirs,’ wrote Pigott praising his own amplifications, then ‘she possesses titles far superior to any, which all the kings in the world have it in their power to bestow.’64 ‘This author’, claimed Erskine,

libelled all those who were entrusted with the Government of the Country, and all those, whoever they were, who were placed in the most respectable situations [in the Jockey Club]; and after having exhausted that sex, he then fastened on the weaker sex, (whom all agreed to protect) beginning with the wife of the Sovereign, [and] the royal princesses.65

There are plenty of examples to choose from. Pigott claimed, for instance, that Lady Archer was as ‘adept in certain manual exercises’, including ‘raising a cock at faro’.66 Condemning aristocratic women for publicly displaying themselves at routs and gaming tables was becoming a familiar part of the growing moralism of public culture, but Pigott’s heady cocktail was far from usual. Throughout the main culprit in terms of public display – the reader is reminded from the Jockey Club – are ‘the stupid barbarous prejudices of Royalty’.67

The Female Jockey Club opposes an enlightenment celebration of natural energies to aristocratic artifice in a way that echoes Holbach’s materialism. Libertine punning often shares the page with a critique of ‘superficial delicacies and luxuries’ opposed to ‘those heavenly enjoyments, which Nature has indulgently yielded, to make the bitter draught of life go down’. The opening entry in the Female Jockey Club condemns the enslavement of the royal princesses to ‘the sterile solitude of celibacy’, reading the royal household in terms of the paternal tyranny regularly attacked in sentimental fiction and the Gothic novel, not to mention much of Robert Merry’s writing. ‘Nature will prevail’, as Pigott puts it in his discussion of the princesses, becomes an over-determined motto as sentimental moralism meets libertine insinuation.68 The collection ran into several editions, including a fourth edition of five thousand copies Eaton claimed, but the publisher did not escape trouble.69 Lady Elizabeth Luttrell brought a libel case against the book for a passage claiming she received ‘select visitors in her private apartments’. There, Pigott claimed, she ‘employed to make herself agreeable … forget her age, and act again the joys of voluptuous youth’.70 A lengthy report of the trial appeared in The Times on 31 July. Erskine, appearing for the prosecution, described Pigott’s book as a ‘supplement to another work of malice [The Jockey Club], which had for its object to libel everything that was virtuous, honourable, and respectable in this country’. Erskine’s role is an indication, if one is needed, of just how far Pigott had become alienated from his old Whig networks. Eaton was found guilty at the end of July, but settled out of court.71 Pigott was beyond such mercies, as several newspapers noticed. He had died in his apartments on Tottenham Court Road at the end of June. John Gurney, Eaton’s lawyer, described him as ‘possessing the ablest head, with the blackest heart … gone to answer for this and all other offences at a higher Tribunal’.72

The gaol fever that had killed many others held in Newgate probably killed Pigott. His body was interred in his family vault in Chetwynd, but his legacy was not so easily claimed by the proprieties of the landed gentry. After his death, Eaton brought out a posthumous copy of his Political Dictionary (1795).73 There are fewer better illustrations of John Barrell’s claim that political struggle in the 1790s was often about the meaning of words.74 In the Political Dictionary, the vocabulary of customary rights and traditional liberties that conditioned most eighteenth-century political discourse is presented as a smoke screen designed to exclude the people from political participation. The attachment to constitutional monarchy is defined in terms of a Whig preference for closed networks of ‘influence’ over democratic transparency:

Whig, - a person who prefers the influence of House of Hanover to the prerogative of the Stuarts. I am an enemy to both; but if we must languish under one or the other, I would, without hesitation, prefer the prerogative of the Stuarts, and for this reason – where prerogative is, the defence and justification of an arbitrary act, all the odium which such an act would, is attached to the king himself; whereas, when this same arbitrary act is induced, through the medium of influence, the odium rests on no one in particular.

Every part of the church and state is subjected to pithy evaluation and dismissal.

The Opposition fares little better than the Ministry. The entry under so innocuous seeming a word as ‘Fulsome’ gives a sense of Pigott’s disdain for the manners of the great. The image of Fox as the ‘Man of the People,’ a target of Pigott’s from at least 1785, is reduced to a public show masking private vice:

Charles Fox eternally passing compliments in his parliamentary speeches on the infamous B-ke. The manner in which members of both Houses of Parliament address each other. Noble Duke, Noble Lord, Right Honorable Gentleman, Learned Friend &c &c &c. This language may very properly be styled fulsome, since it is generally applied to the most unfeeling and corrupt beings of the human race.75

Whig principles are implicitly being opposed to the genuine man of feeling who makes an appearance in the ‘Preface’ provided with some editions. ‘Liberty and Property’, the twin peaks of Whig ideology, he scornfully defines as ‘an indispensable necessity for keeping game for other people to kill, with pains and penalties of the most arbitrary kind, should we think of appropriating the minutest article to the use of our own families’.76

From a Burkean point of view, of course, Pigott’s defection would have illustrated the dangerous moral relativism unleashed by the enlightenment faith in ideas.77 From this perspective, he proved himself ‘the Louse’ who abandoned his class for self-interest masking itself as philosophy. Cut off from the culture to which he was born, Pigott provided a morality tale of the fate of talents and energies unmoored from those English traditions and customs ceaselessly mocked in the Political Dictionary. Eaton presented the case rather differently. Some copies under his imprint publish a first-person preface presenting Pigott as a hero of benevolence, who had sacrificed Gothic manners to republican virtue and human natural feeling. The preface comes complete with Richardsonian asterisks, breaking up the text, as if to indicate that sickness is undermining the author’s sensitive frame. ‘Inequality of style’ is excused by ‘the capricious and fluctuating temper of mind of the author’.78 Whether Pigott intended these words for publication cannot be known, although Eaton published the preface with manuscript directions to the editor. Eaton may have been appropriating papers left by his fellow member of division 25, but he was also presenting his late colleague as a man of feeling ruined by a cruel and unjust system. Certainly this kind of self-revelation has more of the libertinism of Rousseau’s Confessions than Richardson’s Clarissa. The modesty and polite self-command essential to the Richardsonian ideas of sensibility are flouted in the pages of the dictionary itself. A Political Dictionary breathes the spirit of an anti-clerical freethinker, dismissive not only of the moral authority of the elite, but all the institutions of the church and state. The Dictionary displays the same disposition that freethinking members of the LCS were pleased to find in the System of Nature.

One of the few radical writers who had much to say on Pigott’s behalf was Robert Watson, Lord George Gordon’s secretary. Watson never shared his employer’s religious fervour.79 He was very much a marginal figure in the LCS, partly because of his association with Gordon, but he praised Pigott as ‘a patriotic writer’ and his brother Robert as ‘a philanthropist’. No doubt Watson considered Pigott, like his former employer, ‘a martyr to cruel and sanguinary laws’. Watson showed no compunction about identifying the body of Marie Antoinette with corruption and would scarcely have baulked at the Female Jockey Club.80 Others defended Pigott’s principles in the context of reform politics, including George Dyer and Benjamin Flower, but found the personal mode of attack hard to equate with their ideas of benevolence.81 No doubt their friend Coleridge would have included Pigott among those ‘sensualists and gamblers’, including Pigott’s companion Joseph Gerrald, whom he thought dishonoured the name of ‘Modern Patriotism’.82 Gerrald retained a place among the pantheon of radical martyrs, often identified with the daughters he left behind, thanks to the labours of Thelwall and others to consecrate his name. Pigott’s name does not easily fit into any heroic account of the development of popular political consciousness, but after his death his satirical voice became a crucial component in the explosion of radical texts that spewed from radical bookshops in 1795. His name if not his reputation was constantly before the eye of readers on the title pages of one-penny anthologies like the Voice of the People, Warning to Tyrants, and The Rights of Man, published by ‘Citizen’ Lee at the Tree of Liberty.