1 - Reconsidering primate tourism as a conservation tool

An introduction to the issues

from Part I - Introduction

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 September 2014

Summary

Introduction

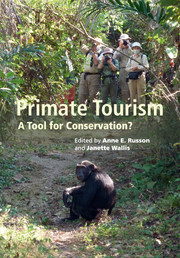

This book aims to assess the conservation effects of nature tourism. In particular, our focus is on tourism to visit nonhuman primates and their habitats. Although humans are also primates, for convenience, we refer to nonhuman primates as “primates” and nature tourism to visit them as “primate tourism.”

Using nature tourism as a conservation tool is not new. It has been advocated since the 1800s, from the view that nature tourism is an impact-free activity that will lead visitors to value nature and help fund its protection (Honey, 1999/2008). Hopes have been especially high for nature tourism that aspires to “ecotourism,” broadly referring to responsible travel to natural areas that conserves the environment and improves the well-being of local people (e.g. Ceballos-Lascurain, 2000; Honey, 1999/2008). It is now well known that even the most ecologically responsible nature tourism is not always the impact-free activity envisioned and it has often failed to deliver on its conservation promises, especially to the conservation of the wildlife and natural areas visited (Higham, 2007). Evidence now shows that adverse effects of nature tourism are widespread (Butynski, 2001; Higham 2007; Knight & Cole, 1995). One result is an increase in calls for evaluative research on whether nature tourism is generating conservation benefits for the wildlife and natural areas visited, what conservation costs it incurs, and whether its benefits to their conservation outweigh its costs (e.g. Higham, 2007).

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Primate TourismA Tool for Conservation?, pp. 3 - 18Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2014

References

- 8

- Cited by