It is often assumed that piracy in Southeast Asia – as in most other parts of the world – came to an end around the middle of the nineteenth century as a result of the resolute efforts of the expanding colonial powers and their navies. Aided by steam navigation and their increasingly superior military technology, the European naval forces were, at long last, able to suppress the large-scale piracy and other forms of maritime raiding that seemed to have plagued maritime Southeast Asia since the dawn of history. As the colonial regimes took control over most of the land in the region, the Malay, Chinese and other Asian pirates were deprived of their markets and safe havens on land. At the same time, increasingly frequent patrols by the colonial navies and other maritime forces made piratical ventures ever more difficult and precarious. The anarchy of the past gave way to the modern regime of relative security at sea, allowing for the freedom of navigation and the progress of maritime commerce, economic development and civilisation.Footnote 1

For the advocates of colonisation the suppression of piracy was (and sometimes still is) hailed as a major achievement and a manifestation of the civilising and benevolent influence of Europe’s and the United States’ imperial expansion.Footnote 2 Colonisation, from this point of view, did not only mean the imposition of law and order on land, but also at sea, enabling people and goods to travel unmolested across the water. Meanwhile, the need to suppress piracy was often used as a rationale for colonial expansion. Sovereignty and the suppression of piracy were intimately linked with one another, albeit in varying and often complex and contested ways.

This book investigates the role of what Europeans, Americans and Asians of different nationalities called ‘piracy’ in the context of the modern imperial expansion in Southeast Asia. The origins of the colonial discourses and practices associated with piracy are traced to the onset of the European maritime expansion in the early modern period, but the focus of the study is on the period from around 1850 to 1920. This focus is in part motivated by the relative scarcity of studies of piracy and other forms of maritime violence in the region beyond the 1850s. Apart from some important studies of the Dutch East Indies, which deal with all or most of the nineteenth century, most full-length studies of piracy in Southeast Asia to date focus on the first half of the nineteenth century or earlier periods in history.Footnote 3

The fact that organised piracy and maritime raiding were brought largely under control around the middle of the nineteenth century, however, does not render the study of the phenomenon obsolete for the remainder of the century or the twentieth century. For one thing, maritime raiding continued to cause problems in parts of maritime Southeast Asia and the South China Sea throughout the nineteenth century and, in some parts of the region, well into the twentieth century. For the most part the victims were Asian seafarers or coastal populations, including Chinese merchants, Malay fishermen, Vietnamese coastal populations and Japanese and other Asian pearl fishers. In addition, some of the attacks that befell Europeans or Americans attracted widespread attention, not only in the region but also in the colonial metropoles.Footnote 4

Second, and most important for our present purposes, the suppression of piracy continued to be an important rationale for colonial expansion even though maritime raiding in itself, for the most part, had ceased to constitute a major security threat for the colonial authorities when imperial territorial expansion began to intensify in the region from the 1870s. As noted by Eric Tagliacozzo, with reference to Dutch and British writers and statesmen at the time, the threat of piracy was most immediate in the decades leading up to 1865, when it constituted a real impediment to the progress of commerce and administrative stabilisation on the peripheries of the Dutch and British colonial possessions in Southeast Asia.Footnote 5 Maritime raiding, however, did not cease in 1865, and the threat of piracy continued to be invoked throughout the rest of the nineteenth century and, in some cases, well into the twentieth century. The suppression of piracy – whether real, alleged or imagined – was thus an integrated part of the intensified process of colonisation in much of Southeast Asia in the second half of the nineteenth century. The perceived threat was not confined to maritime parts of the region but was also invoked in mainland Southeast Asia, particularly by the French in Indochina.

Against this background, piracy can be used as a lens through which the processes of imperial expansion and colonisation and the encounters between fundamentally different economic, social, political and cultural systems can be studied. In doing so the present study aims to provide fresh comparative insights into one of the most formative periods in the modern history of Southeast Asia and the world.

Piracy and Colonial Expansion in Southeast Asia

One of the first questions to ask in an investigation of piracy in Southeast Asia is what actually constituted piracy in the eyes of the actors involved. The terms pirates and piracy appear frequently in early modern and nineteenth-century sources pertaining to maritime Southeast Asia, but what were the reasons for using these and related terms to refer to the various types of illicit activities that usually – but not always – occurred at sea? A central purpose of this book is to highlight the different perceptions of ‘piracy’ held by contemporary Europeans, Americans and Asians of different nationalities, vocations and political convictions. To what extent and under what circumstances were piratical activities seen as troublesome, barbaric or horrific, and to what extent were they seen as trifling, legitimate or even honourable, depending on the point of view of the beholder? When and why did piracy begin (or cease) to be seen as a major security threat by, for example, the colonial authorities, the governments and general public in the colonial metropoles, Asian sovereigns and notables or merchants of different nationalities? Did the problem subside or disappear, and, if so, when and for what reasons? In what measure did the suppression of piracy, from the point of view of the colonial powers, necessitate the conquest of territory and the demise of local rulers and states? Put otherwise, were conquest and colonisation necessary in order to uphold security and the freedom of navigation, or should the invocation of piracy as a security threat or a barbaric practice be understood primarily as a fig leaf meant to conceal other, less honourable, motives for colonial expansion, such as the quest for land and natural resources, or strategic and commercial advantages?

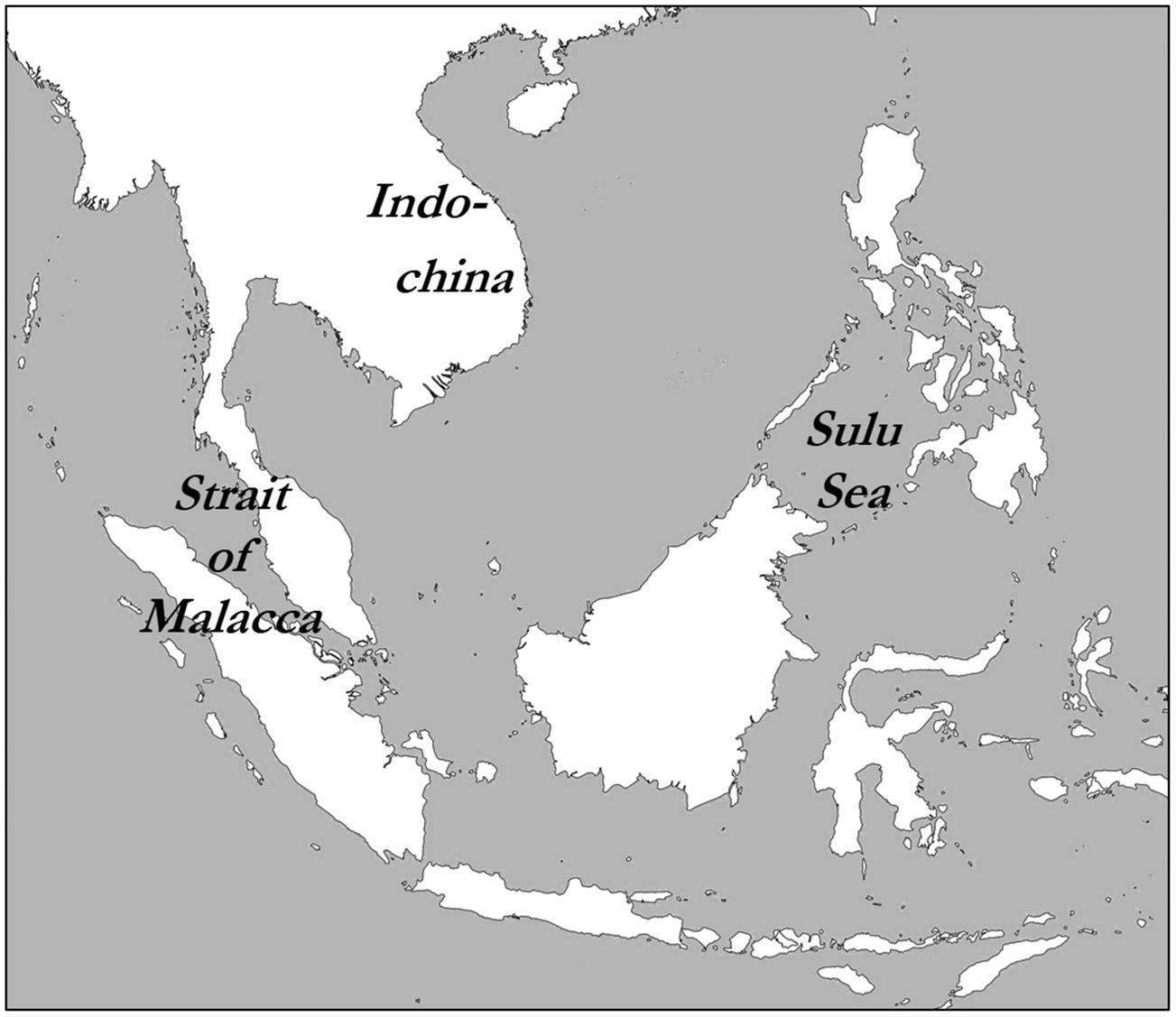

To answer these questions, three allegedly pirate-infested areas in Southeast Asia are analysed comparatively with regard to how piracy was talked about, suppressed and used to motivate colonial expansion (Map 1). The first of these is the Sulu Sea in the southern Philippines. The region was the homeland of the feared Iranun and other maritime raiders, whose depredations surged in the second half of the eighteenth century and reached a climax in the first half of the following century. From around the middle of the nineteenth century, the Spanish naval forces, like the British and Dutch in other parts of maritime Southeast Asia, began to gain the upper hand in the fight against the Sulu raiders, and particularly from the 1860s a more permanent Spanish naval presence in the southern Philippines brought large-scale maritime raiding under control. Attacks on local vessels at sea and coastal raids on neighbouring islands for the purpose of capturing slaves nevertheless continued throughout the Spanish colonial period and during the first decade of the American colonial period from 1899.

Map 1: Southeast Asia

The second area is the Strait of Malacca and the shipping lanes around Singapore and the Riau-Lingga Archipelago, where Malay and Chinese raiders attacked local trading and fishing boats and occasionally large cargo steamers as well. Even though British and Dutch gunboats were able in principle to control the major sea-lanes of communication from around the middle of the nineteenth century, plunder and extortion of riverine traffic, coastal raids and violent attacks at sea, targeting mainly small local vessels, continued for the remainder of the century and, occasionally, beyond. Civil and colonial wars and political instability in the autonomous Malay states bordering the Strait seemed on several occasions to lead to outbreaks of piratical activity throughout the nineteenth century.

The third region is the northwest part of the South China Sea and the rivers of Indochina, where Chinese and Vietnamese pirates and other bandits attacked local vessels at sea and on rivers, and raided villages and settlements on the coast and inland, mainly for the purpose of abducting humans for trafficking. Maritime violence at sea and coastal raiding were largely brought under control by a series of French naval expeditions in the 1870s, but extortion and plunder on Vietnamese rivers and other forms of banditry, as well as anticolonial resistance – all of which was labelled piracy by the French colonists – continued largely unchecked until the last decade of the nineteenth century and resurfaced sporadically even in the early twentieth century.

Several similarities between the three zones provide the rationale for the comparative study. First, the natural geography of all three regions was (and still is in many places) favourable for maritime raiding, a circumstance that was frequently noted by nineteenth-century observers. The coastlines were often thickly forested, and there were many small islands, sheltered bays and hidden passages that provided maritime raiders with safe havens and suitable bases from which to launch their attacks. Many rivers were also navigable inland for vessels of shallow draft and could serve as a means of quick refuge for the perpetrators after raids at sea or on the coast. By controlling strategic points along the rivers, pirates and other brigands, often supported by local strongmen, could control riverine traffic and demand tolls from or plunder trading vessels navigating on the river. As a crossroad for Eurasian maritime commerce, moreover, Southeast Asia has throughout history been amply supplied with richly laden targets for violent attacks. Combined with the seafaring skills of many of the peoples of maritime Southeast Asia, these factors go a long way to explain why the region has figured so prominently in the global history of piracy and why it at times has been regarded as one of the most dangerous regions of the world with regard to piracy and armed robbery against ships – not only in the past, but also in recent years.Footnote 6

Second, most of the coasts and lands of all of the three zones were still by the middle of the nineteenth century governed, at least nominally, by indigenous rulers: the Sultans of Aceh, Siak, Kedah, Perak, Selangor and Johor in the Strait of Malacca region; the kings of Vietnam and Cambodia in Indochina; and the sultan of Sulu in the Sulu Archipelago. However, European colonial powers had begun to make incursions into all of the three zones during the first half of the nineteenth century or earlier and continued to strengthen their presence after the middle of the century. European advances contributed to the destabilisation and decline of the indigenous states, although internal political developments and the repercussions of global and regional dynamics also were consequential. Regardless of the underlying reasons, the decline of the indigenous states and the ensuing disorder and lack of central control paved the way for the imposition of colonial rule in one form or another over most of the three zones between the 1850s and 1870s: by the British in the Malay Peninsula, the Dutch in northern Sumatra, the French in Indochina, and Spain and later the United States in the Sulu Archipelago. In all three zones European advances were met with armed resistance that led to protracted violent conflicts, particularly in the Sulu Archipelago and other parts of the southern Philippines, in Aceh in northern Sumatra and in Tonkin in northern Vietnam.

The third similarity concerns the preoccupation of the colonial powers with the problem of piracy. In all of the three zones, colonial officials and other agents of imperial expansion accused indigenous perpetrators, including not only obvious outlaws and renegades, but also members of the ruling families and other notables, of engaging in or sponsoring piratical activities. The precise nature and frequency of these accusations and the activities they concerned varied, however, and the question of whether the label piracy was appropriate in the different Southeast Asian contexts was the object of considerable contestation by nineteenth-century actors and observers. On the one hand, labelling entire nations and ethnic groups as piratical could serve to motivate European or American military intervention and colonisation. On the other hand, the opponents of colonial expansion, both in Southeast Asia and in the colonial metropoles in Europe and the United States, readily pointed to the flaws of such rhetoric and often rejected any claims that piracy justified colonial wars or the subjugation of indigenous populations. The response of the indigenous rulers of Southeast Asia, meanwhile, varied from active sponsorship of maritime raiding, often as a means of enhancing their own status, wealth and political power, to compliance and cooperation with the colonial authorities in suppressing piracy. Some Asian rulers, such as the sultan of Selangor, seemed indifferent to the problem, whereas others, such as the Vietnamese Emperor Tu Duc, turned the allegation around and accused the French of piracy.Footnote 7 The lines of division in the struggle to define piracy and to identify the best measures, if any, to curb it were thus not neatly drawn between colonisers and colonised, nor between a ‘European’ and an ‘Asian’ understanding of piracy and maritime raiding.

Fourth, and finally, for the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Europeans and Americans who regarded piracy as a serious problem, allegations of piracy were often linked to presumably ‘innate’ ethnic or racial, traits of character associated with certain indigenous groups of Southeast Asia. This was particularly the case with regard to the coastal Malays throughout the archipelago and the formidable maritime raiders of the southern Philippines, such as the Tausug, Iranun and Sama, all of whom by the nineteenth century had acquired a reputation among Europeans for being more or less pirates by nature.Footnote 8

Piracy in Southeast Asia and elsewhere was thus often held up by those in favour of colonisation as a manifestation of the presumed lack of civilisation among the nations and peoples concerned. The failure on the part of indigenous rulers to control illicit maritime violence both within their jurisdiction and emanating from their territories meant that they failed to meet the so-called standard of civilisation, which was the benchmark used by nineteenth-century European lawyers and statesmen to determine whether a state was civilised or not. Lacking the proper laws against piracy and other forms of illicit maritime violence or being unable to control non-state-sanctioned violence within or emanating from its territory disqualified a state from being recognised as a full member of the international community of nations.Footnote 9

Such notions provided a rationale for European and American colonisers’ efforts not only to subjugate but also to ‘civilise’ indigenous peoples in Southeast Asia and other parts of the world. The civilising mission, as put by Jürgen Osterhammel, involved the self-proclaimed right and duty of European and American colonisers to propagate and actively introduce their norms and institutions to other peoples and societies, based on the firm conviction of the inherent superiority of their own culture and society.Footnote 10 In this sense, the civilising mission enjoyed its most widespread influence during the period in focus for the present study, as the economic, political and technological superiority of the West in relation to the rest of the world culminated between the mid nineteenth century and the outbreak of the Great War in 1914. The colonial discourse about and the antipiracy operations in Southeast Asia should thus be understood against the backdrop of the apparent triumph of Western modernity and civilisation at the time and the accompanying conviction on the part of many (but far from all) contemporary observers in both Western and non-Western countries that it was the manifest obligation of Europeans and Americans to civilise and to bring order, progress and prosperity to the rest of the world.Footnote 11

Piracy in the Colonial Lens

The colonisation of Southeast Asia, including the three zones under study here, has been extensively researched ever since the nineteenth century, as have the subjects of maritime violence and the suppression of piracy in many parts of the region, particularly the Strait of Malacca and the Sulu Sea. Historians of French Indochina, by contrast, have shown less interest in the subject of piracy as such, at least with regard to modern historiography.Footnote 12

Despite the obvious differences between the national historiographies of the countries concerned in the present context – including not only the former colonial powers Britain, France, the Netherlands, Spain and the United States, but also the postcolonial states of Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Vietnam – some general features of how the history of colonisation and the suppression of piracy has been written since the nineteenth century can be discerned.

The first historical studies of the colonisation of Southeast Asia were written as the events in question were still unfolding, or shortly thereafter, often by military officers or colonial civil servants who themselves took part, in one capacity or another, in the developments concerned. Much of this colonial-era literature was, as put by Nicholas Tarling, ‘cast in a heroic and imperialist mould’, but there were significant exceptions.Footnote 13 Some European observers were highly critical of imperial expansion and colonialism, or at the very least of certain aspects of it, such as the use of dubious allegations of piracy in order to motivate territorial expansion or the use of indiscriminate violence against militarily inferior enemies.Footnote 14 Read critically, nineteenth-century historiography also contains many valuable clues for understanding the actions and decisions taken by the agents of history from their point of view and for understanding the Zeitgeist of the age of empire in Southeast Asia.

Piracy was a prominent topic of analysis and discussion among nineteenth-century European writers, statesmen, politicians, colonial officials and naval officers in Southeast Asia. Their writings show that the term piracy was not, for the most part, applied unreflectedly to the Southeast Asian context but that it was often highly contested, particularly in the British colonial context. Some texts demonstrate that their authors had substantial knowledge about the historical, cultural and legal aspects of piracy and other forms of maritime violence, both in Southeast Asia and in global historical perspective. Many observers analysed the phenomenon with reference to broader temporal and cross-cultural frameworks, frequently comparing contemporary Southeast Asian piracy and maritime violence with earlier periods in classical and European history.Footnote 15 Although such analyses sometimes were imbued with Eurocentrism, stadial theory and racism, they could also be sincere efforts to understand, and not just condemn or suppress, indigenous piracy and other forms of maritime violence in Southeast Asia.

Without defending the often brutal methods used in the colonial efforts to suppress piracy, it is also important not to lose sight of the fact that, in contrast to latter-day scholars who study piracy in retrospect and from a distance, colonial officials and military officers in the field had to make decisions that had a real effect on people’s lives. They also frequently had to argue for their preferred course of action, not only from legal or pragmatic perspectives, but also from a moral point of view. Writing in 1849, James Richardson Logan, a British lawyer and newspaper editor in the Straits Settlements, described the moral dilemma between taking the side of the perpetrators of maritime violence or that of their victims:

Piracy is doubtless less reprehensible morally in those who have never been taught to look upon it as a crime, but that is no reason why every severity necessary for its extirpation should not be resorted to. A tiger is even less reprehensible in this point of view than a professional pirate ‘to the manner born’. But we must do what is necessary to prevent injury to others from piratical habits, before we can indulge in compassion for the pirate. Our sympathy must be first with the victims and the endangered; with the murdered before the murderer, the slave before the slave dealer.Footnote 16

Although allegations of piracy frequently were deployed for opportunistic reasons, there were strong moral arguments for acting against the large-scale and often brutal maritime raids that affected large parts of the Malay Archipelago in the nineteenth century. The raids often involved the killing, abduction and robbery of innocent victims, including men, women and children, many of whom were forced to endure terrible abuse and hardship. From this perspective – and notwithstanding that other, less noble, motives frequently were decisive in the formulation of colonial policies, and that the measures adopted were at times excessively brutal – it is difficult to see the decline of maritime raiding in Southeast Asian waters from the middle of the nineteenth century as an altogether negative development.

Moral Relativism and Cross-Cultural Perspectives

Compared with most historians of the colonial era, their successors in the wake of the decolonisation of Southeast Asia from the 1940s have for the most part been much less favourable in their assessments of colonial efforts to suppress piracy in the region and of colonialism in general. The use of the very terms piracy and pirate in the Southeast Asian context has been one of the main points of criticism. Among the first scholars to draw attention to the problem was J. C. van Leur, a Dutch historian and colonial official in the Dutch East Indies during the final years of the colonial period. In an article originally published in 1940, Van Leur criticised the tendency of European scholars and observers to belittle Asian civilisations and to pass value judgements on precolonial states in Southeast Asia based on condescending notions drawn from European history and society:

Even without knowing further details, it seems to me inaccurate to dispose of such Indonesian states as Palembang, Siak, Achin, or Johore with the qualifications corrupt despotisms, pirate states, and slave states, hotbeds of political danger and decay. Inaccurate, if for no other reason, because despotism, piracy, and slavery are historical terms, and history is not written with value judgements.Footnote 17

Building on Van Leur’s and other critical views of colonialism that emerged during the interwar years, the 1950s and early 1960s saw the rise of new historiographical frameworks with regard to colonial and imperial history imbued by a more professional historical ethos and methods. Profiting from the greater availability of primary sources, particularly in the form of colonial archives, the efforts to write imperial history tended to focus on political and administrative developments in London, Paris, Madrid and other colonial metropoles. The focus was often on official policy and less on the impact of the policies and the adopted measures in the colonies. Prominent themes included political debates and policy processes and the relations between different branches of the government, the military and the colonial administration. The personal capacity and accomplishments of prominent figures, such as ministers, governors and other senior colonial officials and military officers, were often emphasised, whereas the perspective of the colonised, as in the earlier historiography, rarely was given much prominence, possibly with the exception of the members of the indigenous elites who were in direct contact with the Europeans. Despite the shortcomings of these studies, many of them are still valuable, particularly for their detailed mapping of political and military events based on the careful analysis of voluminous colonial archives and other primary sources.Footnote 18

The foremost authority on piracy in colonial Southeast Asia to emerge in the context of this new paradigm was the British historian Nicholas Tarling. In his early studies of British efforts to suppress piracy in the Malay Archipelago in the first half of the nineteenth century, he took the cue from Van Leur and warned against unreflectedly describing acts of maritime violence undertaken by Asians as piracy.Footnote 19 Tarling noted that piracy carried ‘from its European context certain shades of meaning and overtones which render inexact its application even to ostensibly comparable Asian phenomena’. Because his focus was on British policy, he nevertheless argued that the term piracy was relevant and that it was ‘necessary to be fair to the Europeans who believed they were suppressing piracy’, as it was not unreasonable, in the nineteenth-century context, to consider many of the acts of violence that took place in Southeast Asian waters as piracy.Footnote 20 Thus content with studying piracy, as the term was defined by contemporary British colonial officials, Tarling argued that it would be inadvisable for the historian to attempt to decide what was or was not really piracy in the Southeast Asian context. Neither did he think it would be meaningful or valuable to try to apply the term piracy interculturally, but rather that it was ‘necessary to avoid commitment to irrelevant notions of international law and morality’.Footnote 21

Both Van Leur and Tarling represent what Patricia Risso has called a ‘position of moral relativism’ with regard to the definition of piracy, in contrast to the absolutist (and often disparaging) position taken by most colonial observers.Footnote 22 The dichotomy between the two positions, however, precedes by far the modern historiography of piracy in Southeast Asia. Its origins can be traced to classical Antiquity, and it has a long intellectual history in Europe. Whereas the absolutist view of piracy can be traced to Cicero’s writings in the first century BCE, the relativist position was most influentially formulated by St Augustine of Hippo in the early fifth century CE. His well-known story of the pirate and the emperor is arguably still one of the most eloquent attempts to capture the essence of the relativist position:

Indeed, that was an apt and true reply which was given to Alexander the Great by a pirate who had been seized. For when that king had asked the man what he meant by keeping hostile possession of the sea, he answered with bold pride, ‘What do you mean by seizing the whole earth; but because I do it with a petty ship, I am called a robber, while you who do it with a great fleet are styled emperor.’Footnote 23

The relativist position has been at the heart of the dominating paradigm in the historiography of piracy and maritime raiding in Southeast Asia (and other parts of the world) for most of the post–World War II era. The thrust of the argument is that the term piracy was inappropriately applied by European colonisers to indigenous maritime warfare and efforts aimed at state-building, as well as to malign commercial rivals. The effort by the colonial powers to suppress piracy should, from this perspective, above all be understood as a ‘tool in commercial competition and in the building of empire – bad means to a bad end’, as put by Risso.Footnote 24 Taking the argument one step further, historian Anthony Reid has suggested that the European discourse on piracy in Asia be understood as a form of ‘organized hypocrisy’.Footnote 25

Such analyses, however, are no less imbued with value judgements than the colonial historiography that Van Leur criticised close to eighty years ago. Just as the inaccurate descriptions of the indigenous Malay states as ‘pirate states’ failed to capture the complexity of the social, political and cultural systems in which maritime raiding played a central part, the more recent condemnations of colonial efforts to suppress piracy serve to obscure the nuances and diversity of various forms of maritime violence in the context of the European expansion in Asia from the turn of the sixteenth to the early twentieth century. Not taking the colonial discussions and debates about the problem into account, moreover, gives a distorted picture of the intellectual and political climate of the colonial period and risks producing overbearing claims to having exposed the alleged hypocrisy or high-handed and Eurocentric attitudes of colonial agents rather than trying to understand their attitudes and motivations in the proper historical context.

A further problem with the relativist position is that it is imbued with the very Orientalist assumptions that it purports to overcome.Footnote 26 By positing a dichotomy between a presumptive European and a presumptive Asian (or Chinese, Malay or Southeast Asian, etc.) understanding of piracy, and by portraying the latter as more or less static before the onset of the European expansion, the idea of an Asian understanding of piracy serves above all as a counterimage to the European concept.

The Orientalist bias is even more evident in the exoticising and romanticising claims of piracy as a cultural tradition and an honourable vocation among the Malays and certain other ethnic groups. For example, although Sultan Hussein Shah of Johor may very well have been sincere when he, in the early nineteenth century, supposedly told Thomas Stamford Raffles that what Europeans called piracy ‘brings no disgrace to a Malay ruler’, taking such a statement as emblematic of a presumptive ‘Malay’ attitude to piracy shows a troubling lack of source criticism.Footnote 27 Doing so may even contribute to reproducing colonial stereotypes of the allegedly piratical ‘nature’ or ‘instincts’ of the Malays. Numerous testimonies by indigenous Southeast Asians who became victims of piratical attacks and maritime raids, by contrast, clearly demonstrate that far from all Malays or other Southeast Asians shared such positive attitudes with regard to maritime violence and depredations.Footnote 28

Toward a Connected History of Piracy

From the late 1960s, in the context of decolonisation, the rise of Marxist historiography and a general surge in interest in the history of ordinary people and everyday life, colonial history began to concern itself more with the experiences and perspectives of the colonised. Many scholars were critical of the Eurocentric bias in earlier colonial historiography and tried to redress the balance by writing more Asia-, Africa- and Latin America-centred histories, focusing on, for example, the economic exploitation and oppression of indigenous people and the rise of anticolonial and national liberation movements. Dependency theory and world systems theory also influenced the writing of colonial history, aiming to provide a comprehensive analytical and conceptual framework for understanding the relations between colonies, semicolonies and metropoles. Another source of inspiration for this new colonial history was the emerging field of ethnohistory, which emphasised anthropological methods and the exploration of alternative sources, such as oral history and cultural expressions, in order to highlight the experiences of non-Europeans.

In the context of maritime Southeast Asia, James Francis Warren’s work on the Sulu Zone from the 1980s combined elements of both ethnohistory and world systems theory, and in doing so he succeeded in providing a much-enhanced understanding of the role of maritime raiding in Southeast Asia in relation to the expanding global commercial exchange in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.Footnote 29 Warren, like Van Leur half a century before him, rejected the characterisation of indigenous Malay polities as pirate states, not so much because of the value judgement associated with the term piracy, but because the label piracy tended to obscure the complex fabric of trade, slavery and raiding that characterised the Sulu Sultanate and its dependencies from the late eighteenth until the middle of the nineteenth century.Footnote 30

In his later writings, Warren also tried to overcome the dichotomy between the absolute and relativist positions by arguing for the need to understand the phenomenon of piracy and maritime raiding from both perspectives. Avoiding passing value judgements on either Europeans or Asians, he has argued that it is possible both to understand why the colonial authorities, in view of the devastating effects of maritime raiding in the region, condemned such raiding and labelled it piracy and, at the same time, to realise that such activities, from the point of view of the sultan and coastal chiefs of Sulu, were an important means for them to consolidate their economic base and political power.Footnote 31

Building on Warren’s and others’ attempts to define the concept of piracy from an intercultural historical perspective, a working definition of piracy for our present purposes is

any act of unprovoked violence or detention, or any act of depredation, done upon the ocean or unappropriated lands or within the territory of a state, through descent from the sea and with the capability to use force in the furtherance of these acts.Footnote 32

This definition is intentionally broad in order to encompass the great variety of different forms of maritime violence perpetrated by European as well as Asian navigators throughout the early modern and modern periods. It also seeks to avoid passing a priori value judgements on the perpetrators. In contrast to most definitions of piracy, it also intentionally leaves out the provision that piracy be limited to acts done for private ends, as this raises difficult questions about sovereignty, raison d’état and what defines a legitimate state, questions that cannot be answered a priori, at least not without passing value judgements, with regard to maritime Southeast Asia during the period under study.Footnote 33

The shift from a Eurocentric to a more Asia-centric or globally balanced perspective on the modern history of Southeast Asia has been one of the most important lasting developments in the region’s historiography in recent decades. By comparison, the influence of postcolonial studies has been more limited, at least in comparison with other non-European regions such as South Asia, the Middle East and Latin America. The influence is mainly discernible in the greater interest of historians in previously occluded aspects of colonialism, such as race, ethnicity, gender, and perceptions of time and space.Footnote 34 Following the publication of Edward Said’s book Orientalism in 1978, historians of Southeast Asia also began to take a more critical approach to the Western sources and literature about the region. Consequently, one of the most important influences of postcolonial studies in the field of Southeast Asian history has been the reconsideration of the historian’s relationship to the archives and other colonial sources. As Ann Laura Stoler has pointed out, archives tend to draw the historian into their internal logic, language and areas of interest, while leaving out other aspects that may be at least as important from an academic and historical point of view.Footnote 35 The reassessment of colonial sources and the attempts to use them for answering new types of questions about popular culture and social practices has also been accompanied by a new interest in the examination or reexamination of Asian sources. Several scholars from Southeast Asia, such as Cesar Adib Majul, Thongchai Winichakul and Adrian B. Lapian, have made important contributions to these efforts.Footnote 36

Since around 1990, global or transnational history has emerged as one of the most dynamic fields of historical research and has, in the view of some of the leading proponents of the field, led to a paradigmatic shift in the way in which history is written and apprehended.Footnote 37 The emergence of New Imperial History in the United States and Britain was a part of this development, while at the same time showing strong influences from postcolonial studies. The New Imperial History turn has meant that historians now take a greater interest in the social and cultural impact of colonisation, both in the colonies and the colonial metropoles, and try to put domestic and imperial historiographies into conversation with one another.Footnote 38 As such, the New Imperial History bears a resemblance to the so-called histoire croisée-approach, as developed, originally for the purpose of studying transnational processes in the modern history of continental Europe, by Michael Werner and Bénédicte Zimmermann.Footnote 39

The present study is influenced by the New Imperial History turn, and in particular by a recently proposed approach called ‘Connected Histories of Empire’.Footnote 40 Inspired by postcolonial scholars such as Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Ann Laura Stoler and Natalie Zemon Davis, the approach seeks to uncover the complex and more or less obscure links that operated both within and across the borders of empires. At the heart of the attempt to write connected histories of empire are novel spatial frameworks that focus on the frontiers or borderlands of empires. The interaction and encounters in the contact zones are linked analytically to the developments in both the colonial metropoles and regional centres or nodes of empire, such as Singapore, Saigon and Manila. Influences did not only run between the metropoles, colonies and borderlands of a single empire, but also between the colonies and the often overlapping borderlands of different empires. In focusing on these multiple relations and comparisons between borderlands, colonies and metropoles, the approach seeks to understand Western colonisation and expansion in Southeast Asia as more contested, unstable, undetermined and mutually constitutive than earlier historiography.

The connected histories approach implies that imperialism and colonial domination did not just arise from the relentless spread of global capitalism or the increasing political and military superiority of the West in the nineteenth century. Colonialism was at least as much conditioned by the development of ‘shifting conceptual apparatuses that made certain kinds of action seem possible, logical, and even inevitable to state officials, entrepreneurs, missionaries, and other agents of colonization while others were excluded from the realm of possibility’, as it is put by Ann Laura Stoler and Frederick Cooper.Footnote 41 What was imaginable, moreover, was conditioned both by economic and political circumstances and public opinion in distant metropoles and by the immediate opportunities and constraints in the colonies and their borderlands. These opportunities and constraints, in their turn, were conditioned not only by the relations between colonisers and colonised (or to-be-colonised) peoples, but also by the relations with other colonial governments and indigenous states and centres of power.

In order to grapple with these complex relations and processes, the theoretical framework of Concurrences, as developed by Gunlög Fur and colleagues at Linnaeus University, is useful.Footnote 42 Concurrences implies both the temporal property of two or more things happening at the same time, and competition, taking into account both entanglements and tensions. In doing so, it points to a way of avoiding one of the major pitfalls in the writing of global history: the tendency to overemphasise connectivity and convergence, resulting in a deterministic and even celebratory grand narrative of globalisation.Footnote 43 As a heuristic point of departure, Concurrences directs attention to the universalising perspectives contained in colonialist claims and civilising imperatives, and highlights how such claims and imperatives frequently attempt to subsume or co-opt alternatives, regardless of their validity or influence. By moving beyond an understanding of imperial expansion in terms of simplistic binaries between active agents and passive victims, the historical process of colonial expansion can be fruitfully studied as a series of simultaneous and competing stories of exchange, cooperation, transculturation and appropriation, where non-Europeans always retain a measure of agency. The historian can thereby challenge established historical narratives while remaining alive to the significance of alternative voices and understandings of the world.

These points of departure serve to question the dualism that characterises many studies of piracy and colonial expansion, according to which misleading divisions are drawn between coloniser and colonised, or between Asian and European understandings of piracy and other concepts. The colonial experience is instead understood as conditioned by a series of entangled historical processes that were mutually shaped in engagement, attraction and opposition. For our present purposes, these processes involve both indigenous Southeast Asian rulers and populations and a multitude of European, American and Asians actors.Footnote 44 Despite attempts by historians to label and categorise these actors as, for example, colonisers, naval officers, missionaries, merchants, indigenous rulers, mandarins or pirates, no group of actors was homogenous. To the extent that the categories corresponded to a social, economic, political or cultural reality, there was, as we shall see, great heterogeneity in terms of opinion, interest and outlook within each group.

Method and Sources

Even though this book is based primarily on colonial firsthand sources, it is also deeply indebted to the work of earlier historians. Most of the existing literature − with the exception of general surveys of the history of the region − deal in principal with one particular colonial power or part of Southeast Asia. There are also significant differences in the state of the field with regard to the different colonies and colonial powers in the region. For example, whereas the British colonies in many respects have been thoroughly studied, the Spanish colonial period in the Philippines is less well studied, as is the American period.Footnote 45 Moreover, in contrast to the historiography of precolonial maritime Southeast Asia, there have as of yet been relatively few attempts to write more comprehensive or comparative studies or syntheses of the region’s modern history.Footnote 46 Against this background, this book aims to contribute to a more nuanced comparative understanding of what role piracy played in the colonisation of different parts of Southeast Asia.

A central point of departure for the analysis is the concept of securitisation as developed by the Copenhagen School of Security Studies.Footnote 47 In the present context, studying piracy from a securitisation perspective means paying attention to how different actors – such as colonial officials, local merchants, missionaries, journalists and politicians – tried to draw attention to the problem of piracy and describe it as a major security threat. If successful, such securitising moves led to the implementation of extraordinary measures to deal decisively with the problem, such as punitive military expeditions, colonial wars of conquest, the wholesale destruction of alleged pirate fleets and villages or the annexation of territories believed to harbour pirates.

Studying the process of securitisation helps to highlight why the label piracy, as a legal, political and rhetorical concept, was so prominent in all three zones under study. The purpose is to explain the differences as well as the similarities in how piracy was defined, used and contested in different colonial contexts and at different points of time. In doing so, this book seeks to highlight the influence of the colonial discourses and practices with regard to piracy on the processes of colonisation as well as anticolonial resistance.

The contemporary sources consist of a wide range of conventional colonial sources, including both published and unpublished material, with some emphasis on the former. In contrast to an argument recently made in relation to methods in global history, this book has thus not done away with primary sources as the basis for empirical investigation.Footnote 48 The argument for leaving out primary research would be that multiple archival research would be too time-consuming and extensive for a single researcher to cope with in reasonable time. However, whereas there is some merit to that argument, it is feasible for a single historian to consult extensive collections of published sources, including those from different national and colonial contexts, particularly when these have been digitized and are accessible through online databases and repositories. In fact, this book could probably not have been written before the digital revolution in the discipline of history and other branches of the humanities in recent years, at least not within a few years and by a single researcher.Footnote 49

The interpretation of the sources is in many cases relatively straightforward because the arguments by colonial officials, military officers and other actors in relation to piratical or allegedly piratical activities in different parts of Southeast Asia are generally explicit. The understandings of the problem of piracy and the appropriate ways of dealing with it from the colonial point of view can thus be studied comparatively and in depth with relative ease through the firsthand sources. What is less visible in most of the source material, however, are the concurrent understandings of piracy and maritime raiding held by indigenous rulers, noblemen, merchants, captives and other victims of piracy. Their voices are represented to some extent in the colonial archives and printed contemporary sources – for example, in official letters and transcripts of meetings and interviews − but for the most part their words are filtered through the eyes of European or American interpreters, negotiators and interrogators. In interpreting such pieces of information, the challenge is to read the texts against the grain in order to catch a glimpse of the non-European perspectives and understandings of the limits of legitimate maritime violence. In the absence, by and large, of indigenous sources of relevance to the subject at hand, doing so is often the only way of gaining some access (imperfect and patchy as it may be) to the indigenous perspectives on piracy in Southeast Asia’s age of empire.

Disposition of the Book

This remainder of this book consists of four main chapters and a conclusion. In Chapter 1, which provides a conceptual platform and a historical background for the three subsequent chapters, the concept of piracy is analysed in global historical perspective, and its etymology and intellectual origins in Europe are traced to classical Antiquity. The role of piracy in European expansion is highlighted, with a special focus on the encounters between Asian and European understandings of piracy and other forms of maritime violence during the early modern period.

The subsequent three chapters make up the core of the empirical investigation. Each chapter deals with one of the geographic areas under study and focuses on one or two of the five major colonial powers in Southeast Asia in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Chapter 2 deals with Spanish and American understandings of and policies with regard to the allegedly piratical Moros of the Sulu Archipelago, particularly from the middle of the nineteenth until the early twentieth century. Chapter 3 analyses British and Dutch uses of the concept of piracy in the context of their commercial and political expansion in and around the Strait of Malacca with an emphasis on the third quarter of the nineteenth century. Chapter 4, finally, deals with French discourse and practices in relation to piracy and other forms of banditry and anticolonial resistance in Indochina from the time of the intensified French expansion in the region in the mid nineteenth century until the 1890s. A summary at the end of each chapter highlights the main comparative insights and conclusions from the study of each region. Finally, the Conclusion draws together the main results of the investigation as a whole, and the Epilogue briefly reflects on the resurgence of piracy in the post–World War II era in the light of the colonial system and its demise around the middle of the twentieth century.