Book contents

- Mobilizing the Russian Nation

- Studies in the Social and Cultural History of Modern Warfare

- Mobilizing the Russian Nation: Patriotism and Citizenship in the First World War

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Book part

- Note on Usage and Translation

- Chronology

- Introduction Mobilizing a Nation

- 1 A Sacred Union

- 2 National Mobilization

- 3 “On the Altar of the Fatherland”

- 4 “All for the War!”

- 5 United in Gratitude

- 6 Fantasies of Treason

- 7 “For Freedom and the Fatherland”

- Conclusion

- Select Bibliography

- Index

- References

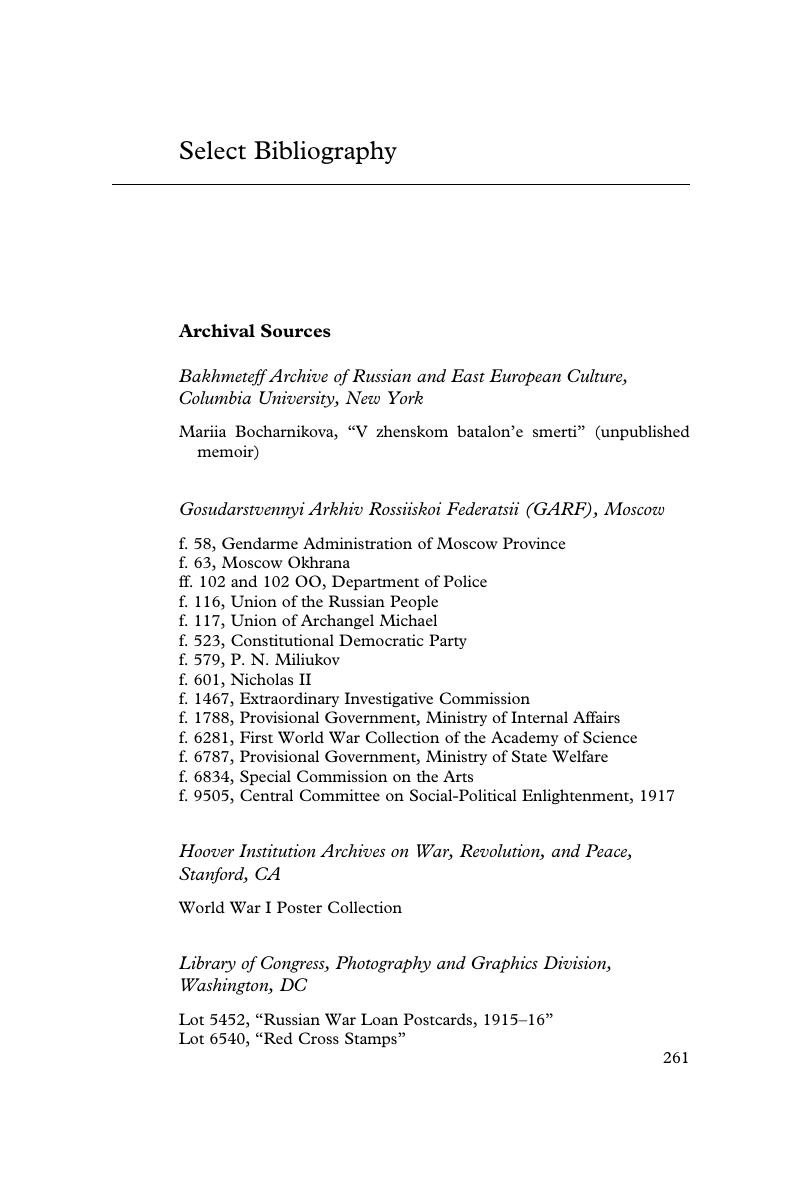

Select Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 25 November 2016

- Mobilizing the Russian Nation

- Studies in the Social and Cultural History of Modern Warfare

- Mobilizing the Russian Nation: Patriotism and Citizenship in the First World War

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Book part

- Note on Usage and Translation

- Chronology

- Introduction Mobilizing a Nation

- 1 A Sacred Union

- 2 National Mobilization

- 3 “On the Altar of the Fatherland”

- 4 “All for the War!”

- 5 United in Gratitude

- 6 Fantasies of Treason

- 7 “For Freedom and the Fatherland”

- Conclusion

- Select Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Mobilizing the Russian NationPatriotism and Citizenship in the First World War, pp. 261 - 276Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2016