In the previous nine chapters linguistic layers of identity were construed as separate areas of research. This organization of the epistemological construct proposed in the present monograph has distinct advantages given that the techniques deployed in the exploration of each layer differ and that there are significant differences in the focus and structure of the layers, the role of the elites and the speakers, and the intervention type. However, this does not mean that the layers are isolated and that no communication between them exists.

There are many ways in which the three layers of lexical identity are connected. Let us consider the following example. Popović (Reference Popović1955:7), writing about Serbo-Croatian, notes its connections with two groups of languages:

Sa jednima je u genetskoj vezi, tojest s njima ga vezuje zajedničko poreklo … Sa drugim jezicima nije u genetskoj vezi … ali ga je u realnu vezu dovela istorijska stvarnost: zajednički život na istom tlu … ipak se i do danas srpskohrvatski jezik tretira izolovano, kao da od vremena izdvajanja iz opšteslovenske zajednice nije primio nikakve elemente sa strane. Razume se da je ovakav lingvistički romantizam i “rasizam” jednostran i nedijalektički.

(With one group of languages there is a genetic relationship, i.e., it is tied to them through a common origin … with other languages it is not a genetic relationship … however historical reality, i.e., life together at the same territory, brought those languages together … Nevertheless, even to this day Serbo-Croatian is treated in isolation as if no elements from other sources were adopted since its separation from the common Slavic community. Needless to say, this linguistic romanticism and “racism” is one-sided and non-dialectical.)

Popović advocates the idea of the importance of lexical exchange, in addition to the deep layer, and he also expresses his negative attitudes toward conscious maneuvers in the surface layer aimed at the suppression of the importance of the exchange layer.

If we look at some concrete examples, the connection between the two layers will become more obvious. In Russian, there are pairs of word stems where one of them is originally Russian and the other is borrowed from Old Church Slavonic, e.g., Russian word: голова ‘head, anatomically’; Old Church Slavonic borrowing: глава ‘head, of a committee, etc.’ Russian word: ровный ‘even, i.e., flat’; Old Church Slavonic: равный ‘even, i.e., equal’. Most commonly in these pairs of roots, the original Russian form is more concrete and the borrowed Old Church Slavonic form more abstract. The process of borrowing (i.e., a process from the exchange layer) has eventually created a distinction in the deep layer, given that many languages will not have lexical distinctions of this kind. Similarly, in Serbo-Croatian, lexical borrowing from Turkish (of the words that eventually can be from various other Near and Middle Eastern sources) has created pairs of words, where one is either from the inherited Slavic stock or borrowed from a Western European language. In these pairs, the Turkish borrowing is stylistically marked as restricted in some way while its counterpart remains neutral, e.g., inherited Slavic oprostiti ‘to forgive’: a borrowing from Turkish halaliti ‘to forgive, restricted to the use in Islam and colloquially in some regions’, a borrowing from German klozet ‘toilet, neutral’: a borrowing from Turkish ćenifa ‘toilet, archaic or regional colloquial’.

All this is not unlike the pairs in English stemming from the Norman Conquest, where the Anglo-Saxon words typically mean something more concrete, and Old French words something more abstract (or processed, sophisticated, etc., semantically or stylistically) as in Anglo-Saxon cow, pig, deer, thinking, wish, wild versus Old French borrowings beef, pork, venison, pensive, desire, savage. Here too, a process in the exchange layer has led to language-specific distinctions in the deep layer.

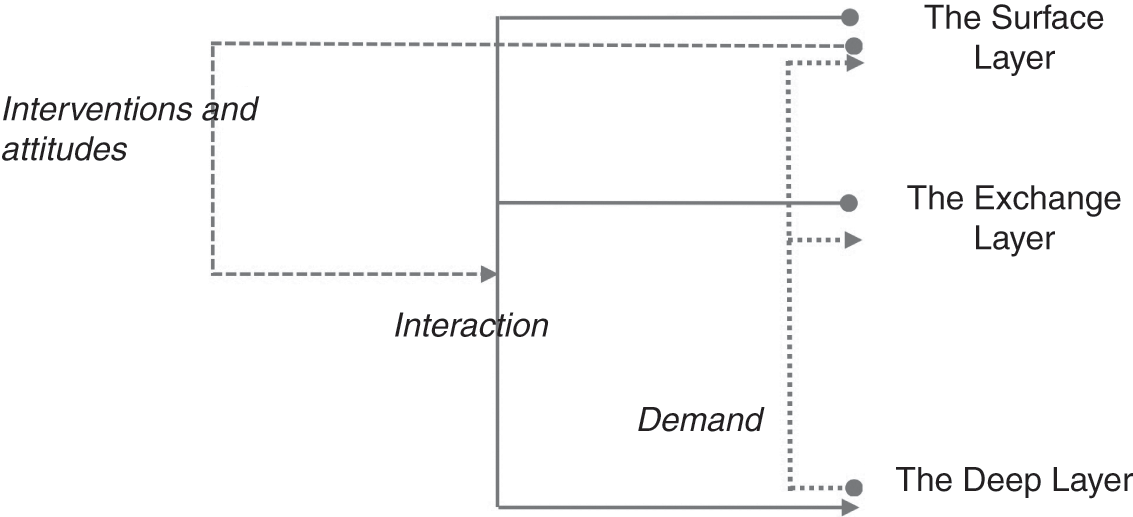

In the present chapter I will outline a unified model of interaction between the three layers. While each layer represents a distinct object of research with its specific features (as previously shown in Chapter 3 and elaborated in Chapters 4–6 for the deep, 7–9 for the exchange, and 10–12 for the surface layer), there still exists the need to explore the interaction between them, given that some phenomena cut across the borders of the layers. Sociocultural and technological changes in the environment in part trigger the movements in the exchange and surface layers, but they are also determined by the fact that the lexical material in the deep layer is insufficient to accommodate the changes in the environment. The need for information from the deep layer is thus a stimulus for the processes of the other two layers. These two layers, on the other hand, are the venue where new lexical units are introduced (by lexical exchange or engineering), which eventually may lead toward rearranging the distinctions and the density of lexical fields in the deep layer. The surface layer, in turn, operates with interventions and attitudes (e.g., of purism or laissez-faireism) on the material from the exchange layer (such as acceptable and not acceptable introductions of new words, delegitimization of existing words) or directly on the material of the deep layer (in case no borrowed lexemes are encompassed by the maneuver, e.g., the one in which the elites postulate incorrect use of an inherited Slavic word). These relations are depicted in Figure 13.1.

Figure 13.1 Interaction between the three lexical layers of identity

The interaction of the layers was evident in the previously discussed nineteenth- and late twentieth-century Croatian maneuvers in the surface layer (more information can be found in Thomas, Reference Thomas1988 and Langston and Peti-Stantić, Reference Langston and Anita2014). There was a demand for new lexical items that were not available in the deep layer, or for a redistribution of the existing lexical items. Both were triggered by a broader environment and its sociopolitical and technological changes. Maneuvers of lexical planning intended to meet those demands are confronted with the attitudes of the speakers. Some of them have stabilized and become a constituent of the deep layer; in case of others, either an exchange lexical item or status quo have prevailed and an engineered lexicon has not been accepted. As previously emphasized, the surface and the exchange layers operate in conjunction with the deep layer, which in turn eventually includes not only the inherited lexicon that evolves over time but also borrowed and engineered words that have stabilized in the deep layer.

The layers are also connected at the level of speakers. Speakers are culturally defined by all three lexical layers concurrently. They function in the deep layer generally without agency and cognizance of what is determining them culturally. They are generally cognizant, but their agency is extremely limited in the exchange layer, while the surface layer features their full agency and cognizance. What connects the three layers are the mental lexicons of the speakers and their linguistic behavior pertaining to lexical choices and evaluations alike. That is where they coexist and interact. The features of the words, such as borrowed or inherited, standard or non-standard, are linked in the speakers’ mental lexicons with the words in the deep layer, which carve out the conceptual sphere in sharing it with other words, that have their own internal semantic structure, that participate in idioms, lexical relations, word formation, and associative networks. Any choice that speakers make in using or not using the words affected by a maneuver in the surface layer is also related to the other two layers. It contributes to a broader or narrower use of the words from the deep layer, and it often concerns the features from the exchange layer (e.g., in the case that the maneuver is a purist one).

To demonstrate this, I will use an example from the 1990s, a real-life laboratory of lexical changes in all Slavic countries (given the transition from communist systems and planned economy to capitalism and free-market economy along with all technological and lifestyle changes that were also happening elsewhere). These changes were particularly far-reaching in Serbo-Croatian, which combined these changes with the revival of nationalism and religious zealotism. I will take the following three Croatian word cohorts that came under the spotlight during the 1990s and that exemplify a range of possible situations in lexical engineering, refereeing, and the dynamics of the relationship between the elites and general speakers: sučelje:interfejs ‘interface’, privreda:ekonomija:gospodarstvo ‘economy’, pasoš:putovnica ‘passport’.

The word for computer interface was a lexical lacuna in the deep layer, which needed to be filled once computers became widely used by the general population of the speakers. This triggered the lexical borrowing of the English term, which also activated the exchange layer, but there was also a maneuver in the surface layer to use a word created from the existing material (which again involves the deep layer), namely combining: su- ‘next to (prefix)’, čelo ‘front (of a head)’, and ‘-e ‘object, device (suffix)’. The lexical planning maneuver in the surface layer involved negative lexical refereeing of the borrowed lexical item and the engineering of the new word. Speakers were confronted with the possibility of accepting the lexical maneuver (which would then block the item in the exchange layer) or rejecting it and using the borrowed lexical item (which would block the surface-layer maneuver). In the end, both lexical items were preserved and the attitudes of the speakers created a type of variation which culturally defined them, as they had a choice of using either of the two terms or both of them. This choice process then varies from speaker to speaker and from situation to situation. It should be clear by now that the situation involved all three layers and their interaction.

The nest privreda:ekonomija:gospodarstvo ‘economy’ was even more complex. The pre-1990s deep-layer situation in all Serbo-Croatian variants encompassed two closely related words: privreda ‘economy’ and ekonomija ‘economics’. The first word is a nineteenth-century engineered word, which roughly means ‘contribution to the value’. The second word is a borrowing from Latin via German and French. In the 1990s there was a maneuver in Croatian to replace the word privreda with another engineered word, i.e., gospodarstvo (gospodar is ‘owner’ and -stvo is the suffix which roughly means ‘the field of’). This word was used at some point in nineteenth-century Croatian, but its revival was primarily modeled after Slovenian, which has been using that word since the nineteenth century. The sole purpose of the maneuver was to emphasize the Croatian ethnic identity at the time when the Croatian state was created – the maneuver was not purist; both involved words were ultimately of the inherited stock. The maneuver was generally accepted by the speakers of Croatian and the word privreda is not used anymore in this variant of Serbo-Croatian (it is continuously used in its other variants). However, the influence of the exchange layer and the fact that economy and economics sound similar in English brought about the same process in all variants of Serbo-Croatian. The word ekonomija is now used to mean not only ‘economics’ (which has never changed) but also ‘economy’. Eventually, the speakers of Croatian began having a deep-layer distinction for using formal gospodarstvo (from the surface layer) and informal ekonomija (from the exchange layer). Again, the example features intensive interaction of all three layers and a negotiated outcome where speakers’ attitudes operate on the elites’ maneuvers.

Finally, pasoš, a borrowed word, was used in Croatian for ‘passport’ before the 1990s, when there was a maneuver to replace it with an engineered word putovnica (put ‘trip, travel’ and –ovnica ‘document (suffix)’). The engineered word was loosely based on Slovenian potni list ‘travel document’. Its primary purpose was to emphasize the Croatian ethnic identity by using a word different from Serbian. The maneuver was eventually accepted and pasoš is used only marginally (it continues to be used in all other variants of Serbo-Croatian). Again, all three layers were involved.

The way in which the exchange layer shapes the deep layer can be seen in the differences of naming certain animals in Slavic languages, in comparison to the same process in English. In Slavic languages, where there was no interference from the exchange layer, the deep layer featured word-formation links between the name for the animal and the name for its edible meat. For example, in Russian there is свиня:свинина ‘pig:pork’, теля:телятина ‘calf:veal’, олень:оленина ‘deer:venison’, that is, names for the meat are suffixally derived from animal names. In English, in contrast, the lexical exchange induced by the Norman Conquest has eliminated these links as in pig:pork, calf:veal, deer:venison.

To demonstrate that an interaction of this kind is by no means restricted to the South Slavic or Slavic realm, one can mention a well-known example of the multiword unit silk road. The term was actually introduced by a German geographer by the name of Ferdinand von Richthofen in 1877 (Waugh Reference Waugh2007:4) as Seidentraße ‘silk road’, that is, it is something that was engineered in the surface layer. It was then a part of the exchange layer to be adopted in all major languages. Curiously, one of them was Chinese which features 丝绸之路, Sīchóu zhī Lù ‘route of silk’, now a part of the deep layer, with speakers being unaware that this is not an ancient Chinese term.

There are numerous other examples like this that can demonstrate the interaction of the three layers either in the times of intensive lexical changes or in less turbulent times. It is important to understand that the general parameters of the deep or even exchange layer do not change with scores or even hundreds of words like the ones used to exemplify the interaction. The changes happen when a critical mass of words or their features is reached and it is impossible to point to its exact moment, as the change, like any other in historical linguistics, assumes a gradual process that takes prolonged periods of time to complete. General lexical distinctions in the deep layer or a general presence of a borrowed lexicon in the exchange layer (that culturally defines speakers) is still there, even after the abrupt period of changes, given that the changes affect only limited vocabulary ranges (as we could see in the example of the new Serbo-Croatian words in the 1990s that was discussed in Chapter 12).

It is also important to note that the demand from the deep layer is a reaction to triggers from the sociocultural environment (which was also apparent from the analysis in Chapter 12). These triggers range from the need to introduce new words to cover a conceptual sphere as a consequence of technological advancement, to the need to replace existing words to emphasize ethnic identity or enforce a specific form of the standard lexicon and hence linguistic authority.

Having pointed out the areas of interaction between the layers, the fact should be repeatedly stressed that each of the three layers features specific ingredients that profile the speakers’ cultural identity in a way that is different from the other two layers. Similarly, the research techniques for the study of the linguistic markers of cultural identity are different in each one of the three layers.

The present monograph advances a proposal for a more systematic study of lexical layers of cultural identity. What is proposed here is an epistemological construct which outlines lexical phenomena that profile cultural identity and the techniques that may contribute to a more systematic exploration of these phenomena. The proposal made in this book is merely an epistemological construct, that is, the only claim made about it is that it represents a convenient tool for a more comprehensive and systematic study of lexical markers of cultural identity. It is also a call for a new cultural linguistic program and, as all pioneering proposals, it only outlines a possible research direction without giving definite answers to any questions.

The review of the relevant research in the field shows that approaches such as Russian linguistic culturology, the Natural Semantic Metalanguage (NSM) theory, and cultural linguistics deserve due credit for bringing the attention of the research community to the nexus of language and culture. This was an enormous achievement in light of the fact that the dominant, so-called formal approaches, such as the minimalist program (Chomsky, Reference Chomsky1995) or optimality theory (Kager, Reference Kager1999) completely excluded these phenomena from linguistic analysis, concentrating exclusively on what is common in the languages of the world, thus mostly on syntax and phonology.

However, the “cultural turn” in linguistics leaves unresolved the following problems and consequently does not address potential areas of improvement.

a. Isolationism: cultural practices in language are analyzed as having no connection to cross-cultural psychology and other similar approaches. For example, a well-known parameter of collectivism versus individualism is not of interest to “linguoculturologists.”

b. Particularism: there is no connection to other fields of Slavic scholarship, e.g., the study of loanwords, which may have established certain culturally relevant distinctions in the lexicon.

c. Elitism: this approach exaggerates the role of literature, intellectuals, etc. – some cultural features may exist in literature, or in a narrow elite group from a population, and be absent from the mental lexicons of the majority of the population.

d. Atomism: the analysis is often overly fine-grained to be applicable; it goes into very peculiar features of one or several words.

e. Determinism: the authors commonly postulate a possible cause of a feature, leaving no room for random events.

f. Ethnocentrism: the authors seem to be equating an ethnic group with a particular language, like talking about Russian, or any other, national mentality, etc., while in reality every language is used by various ethnic groups with their distinct cultures.

g. Arbitrariness: only words that supposedly prove the claim are chosen, while other cases that do not confirm the claim are disregarded.

In reaction to all the aforementioned problems, I proposed here a model comprising three lexical layers of cultural identity: the deep, the exchange, and the surface layer. The deep layer entails specific words, specific ways in which those words divide the cognitive and affective space of that given culture and the way they are connected with other words. This layer encompasses stable lexical strata where changes are only glacial and where any conscious interventions are only marginal and remote. The speakers are given those specific lexemes, distinctions, and connections, which simply shape their cultural identity without their knowledge or consent. At its core are the most common lexemes, which offer the strongest contribution to the profiling of cultural identity given that the speakers are exposed to them more frequently than to any other lexemes (no matter how culture-specific they may be).

The exchange layer comprises the lexemes resulting from cultural contacts with other people. This layer is also given to the speakers without their consent, but, unlike the deep layer, they generally have an idea about the main sources of lexical influence on their language and they can often recognize the word as being the product of such influence. What shapes a speaker’s cultural profile in this layer are the features of the words (rather than the words themselves) borrowed from a certain cultural or contact environment. Some very limited possibilities of intervening in this layer exist (e.g., in the form of purist maneuvers from the surface layer), but generally, none of these interventions change the general landscape of cultural and contact influences. These influences can be stronger or weaker, depending on the concrete subject-matter field, so the distribution of fields (rather than the general core-periphery structure) is important in shaping the speakers’ cultural profile.

The surface layer is the area of an unstable lexicon where cultural identity is a result of constant negotiation between linguistic elites and the general body of speakers. Practically any lexical sphere can be affected by normative intervention. The intervention is conscious, direct, and conducted by linguistic elites (such as linguists, writers, journalists, legislators). The intervention is transmitted through public discourse and the school system, to eventually meet certain attitudes by the general body of speakers, leading to their acceptance, partial acceptance, or rejection, which gives the body of speakers ultimate control over the development of this layer. Cultures and their speakers differ in the prominence of linguistic elites and their intervention, in the strength and centrality of the attitudes of the speakers. The lexicon of the standard language is the ultimate product of this negotiation between the elites and the speakers. Speakers’ cultural profile is determined by the fragmentation of this lexicon and the distance from similar standard language forms.

The present epistemological construct of the three lexical layers of identity is intended to eliminate the aforementioned shortcomings of mainstream cross-cultural anthropocentric linguistics. First, the three layers require a methodological apparatus from cross-cultural linguistics (mostly in the deep layer), contactology (i.e., the study of linguistic contacts, in the exchange layer), and lexicological sociolinguistics (in the surface layer). Second, the methodological apparatus from all three linguistic approaches should be connected to the dimensions established in cross-cultural psychology and anthropology. In addition to these three innovations, the following principles of analysis were advocated and demonstrated:

a. Comprehensiveness: all members of the category are analyzed rather than just those individual cases that confirm research claims.

b. Sensitivity to stakeholders complexity: the analysis distinguishes between the body of speakers and linguistic elites and sees both these entities as most diversified collectives.

c. Multi-perspectiveness: various linguistic and extra-linguistic perspectives are brought into the analysis.

d. Linguistic autonomism: this recognizes that languages do not necessarily have to overlap with ethnic groups and that linguistic identity concerns speakers of languages rather than members of ethnic groups.

e. Sensitivity to linguistic complexity: this recognizes the complexity of language varieties, such as dialects and ethnic variants.

f. Limited determinism: there is an understanding that some developments are random and the analysis can account for only a part of phenomena.

g. Explanatory succinctness: the simplest possible explanatory tools are sought to encompass the broadest and widest fields of the phenomenon being explained.

As noted in Chapter 3, in its core, the model comprises the deep layer (which consists of relatively stable lexical distinctions and includes core research on language and culture), the exchange layer (which involves slowly evolving material from the lexical transfer between different languages and their cultures and includes linguistic contactology), and the surface layer (comprising an engineered and a refereed lexicon susceptible to rapid changes, involving sociolinguistic research). The characteristics of the three layers are presented in Table 14.1.

Table 14.1 The characteristics of the three lexical layers of cultural identity

All these factors within the three layers are distilled into a lexical profile of cultural identity of the speakers of any given language. There is a great deal of overlap in the content of that profile between individual speakers but also significant variation in some of its segments (see Trudgill, Reference Trudgill2001 for more details about variation). Part of the variation will be based on factors such as the speakers’ age, gender, some on factors such as the territory of their residence and ethnicity, and some part of it is governed by the factors that are too complex and unpredictable to be explained.

The speakers’ lexical profile is determined by the words used in a particular culture, but not in most other cultures and their languages. Much more so than certain words (typically names of local customs, foods and drinks, musical instruments and dances, etc. with an occasional abstract concept), however, the speakers’ lexical profile is shaped by the distinctions that a particular lexicon makes in the field of most common words (e.g., if the language differentiates between the words for hand and arm, older and younger brother, neck of a person and that of an animal, etc.). They are furthermore defined by the internal semantic structure of their words, e.g., whether the word bed extends to mean river bed, bed of flowers, etc., or not. Finally, the way the most common words connect in lexical relations (e.g., how many synonyms the word meaning ‘bad’ will have), participate in idioms, have association links (e.g., what the word for color ‘red’ is most commonly associated with) and word-formation networks (e.g., in how many derivatives, compounds, and idioms can one find the word for ‘mother’) also culturally profile the speakers. Various segments of the lexical cultural profile are in part expressions of broader cultural dimensions (individualism/collectivism, low/high contextualness, polychronism/monochronism, etc.). To use a very obvious example, in high-context cultures, the words for evaluating anything will have a range of contextually driven meanings, sometimes opposite from the first meaning of the word, as in using OK as an unfavorable evaluation of a meal, movie, or event. All of the aforementioned parameters are given to the speakers. They unconsciously act inside their lexical profiles without any real possibility to change anything. Similarly, any direct interventions in this lexical sphere would be destined to fail. The variation between the speakers is relatively modest, at least in the core of the most common words and their meanings. The principal driver of the variation is the linguistic education of the speaker, the fact that some will know more words, their meanings, and the links between them than others (in common parlance this would be the difference between more or less “cultured” or “well-read” speakers).

The next two layers, exchange and surface, operate on the material of the deep layer in that lexical borrowings fill gaps in the deep-layer vocabulary or compete with its existing words and meanings, and surface-level maneuvers almost always include the deep-layer vocabulary in the maneuvers of lexical engineering and refereeing. In numerous instances, they also include the exchange layer. What is most important is that the speakers’ cultural profile is determined by the other two layers in a very different way.

What determines the speakers in the exchange layer are the features of the lexemes. First whether the feature is inherited or borrowed, and then what is the source of borrowing (cultural or contact). Another relevant feature is the subject-matter field of borrowing, as some subject-matter fields feature an increased number of borrowings from certain macrolanguage sources. This layer is then thematically organized. The distribution of macrolanguage imports in the general vocabulary and particular subject-matter fields is given to the speakers, but, unlike in the deep lexical layer of cultural identity, they are generally aware of the features that define them culturally. For example, even modestly educated speakers of all Slavic languages will be aware of the classical, Greek and Latin, origins of parts of their vocabulary; while German lexical influence will typically be known even to most uneducated strata of users of the standard language in most Slavic languages. Over a prolonged period of time and collectively, speakers have the potential of making changes in the ratio of the inherited and borrowed lexicon (e.g., by accepting a purist maneuver in the surface layer, which eventually changes the exchange layer). However, the general distribution of sources of borrowing and of their subject-matter fields are the kinds of elements that are not conducive to rapid changes. Most often, purist maneuvers, even if they are successful in enforcing an engineered word, do not expunge the borrowed one from the vocabulary – as a rule, they remain in the standard language, either with lower frequency or a limited field of usage. The changes here are faster than in the deep layer, but they are still very slow. They do not happen before our eyes as they do in the surface layer. While a loanword may enter the vocabulary abruptly and it may equally abruptly be supplanted by another word, it takes decades and most commonly generations of speakers to change general proportions in the lexicon. By the same token, the presence of elites is limited here. They may resort to macro- and micro maneuvers in the surface layer, but they cannot really change the general parameters of the exchange layers that culturally profile its speakers (e.g., dramatically decrease the number of Near Eastern borrowings in Croatian or dramatically increase their number in Bosnian, both of which would amount to linguistic nationalism). That also means that their lexical interventions are only indirect – by direct maneuvers in the surface layers, provided that the attitudes of the general body of speakers toward them are favorable, and with the flow of time, some proportion of the features defining speakers’ cultural profile in this layer might change. Even this indirect intervention is difficult to assess. For example, the proportion of Near Eastern words in today’s Serbo-Croatian (and its Bosnian variant which claims principal cultural heritage to this lexical sphere) is considerably smaller than a century ago. However, it is difficult to say how much of that change is a result of the conscious interventions of the elites (including a general pro-European orientation, ironically enough, triggered in part by Kemalist reforms in Turkey) and how much of it is a consequence of simple obsolescence of the entities that were named with these words (such as old trades and their tools, meals, customs).

The surface layer, unlike the previous two, is a place of abrupt changes in consequence of negotiation between interventionalist elites and the general body of speakers. These changes can happen practically anywhere in the lexical system. Just as in the exchange layer, what contributes to the cultural profile of speakers are features of the lexemes – this time those that exclude them from the standard lexicon, restrict them to only some genres or speech situations, or exclude them from the lexicon of the standard language. Speakers are keenly aware of the changes in this layer and they take an active stance toward them. The layer is dominated by the elites and their direct interventions, but the speakers enjoy true agency and eventually have the final say on which macro maneuver is going to take hold. What comes about as an ultimate consequence of this negotiation between the elites and the speakers is a particularly shaped lexicon of the standard language. In the surface layer, speakers are culturally defined by their range of possibilities of accepting and rejecting interventionist maneuvers (which may be weaker or stronger, unified or fragmented, etc., depending on the standard language and its culture). Speakers are also defined by the features of their particular standard language lexicon. Thus, a speaker of Czech is defined by how strictly he/she enforces the difference between standard and common Czech and also by the fact that standard Czech is closely related and defined in a way by common Czech. A speaker of the Croatian variant of Serbo-Croatian is defined by his/her possibilities in accepting or rejecting the use of the so-called proper standard Croatian lexemes. These most often include avoiding forms that Croatian has in common with Serbian, in those cases where there is a specific Croatian word. This speaker is also determined by the fact that the Croatian variant is defined by its relationship with other variants of Serbo-Croatian.

What should have become evident from the nine core chapters of this book and the present review of the main findings is that the cultural identity of a speaker of any language is defined by a considerably broader range of factors than key words, cultural scripts and concepts, etc. A speaker is defined by the distinctions within his/her core lexicon (which includes the aforementioned keywords, scripts, and concepts). At the same time the speaker’s cultural identity is determined by the cultural influences and neighboring languages that have contributed to the lexicon of their language and by their negotiation of the interventionist elite maneuvers. All this should be included in the speakers’ lexical profile of their cultural identity. It should also be clear by now that there is a range of research techniques and readily available lexical datasets that have the potential to make important contributions to our understanding of the lexical layers of cultural identity.

Throughout the present monograph, I have used examples from Slavic languages. Along with demonstrating the points about the factors that are lexically profiling speakers’ cultural identity, the goal of these examples was to show that Slavic studies in lexicology and linguistics still make sense. As should have become apparent, especially from the examples in the deep layer, the idea of Slavdom (discussed at length in Chapter 1) still plays a role in the cultural profiling of each particular Slavic language – there are wide ranges of overlapping inherited lexicon, there are closer or more distant patterns of continuation and change between various Slavic languages, there are shared sources of cultural influences, and so on. Perhaps more importantly, in a great body of Slavic dictionaries and lexicological monographs there is a wealth of readily available data that can be explored in elucidating the lexical layers of cultural identity of the speakers of Slavic languages. Their number and variety were considerably richer before the process of dissolving traditional philology into general linguistics on the material of Slavic languages and comparative literature (again, using Slavic writers). Nevertheless, their influx is steady even in this day and age. Perhaps the time is ripe to solve the dilemma of having Slavic departments and organizations across the English-speaking world but no consistent research traditions of Slavic studies in linguistics. What I hope to have shown is that Slavic studies offers almost endless research possibilities in elucidating lexical layers of cultural identity. What I hope to encourage is the idea that Slavic departments and organizations become venues for Slavic linguistic research, rather than Slavic languages serving only as a source of examples for research on general linguistic problems.

In this chapter, I will outline the prospects of further research in this field. Examples provided throughout the present monograph are intended to exemplify the range of data to be included in the research of the lexical layers of cultural identity and the techniques of a consistent analysis of that data. They definitely do not build complete cultural-lexical profiles of any languages that were used and not all processes and features are characteristic for all Slavic languages. Neither do they represent an in-depth analysis of any discussed phenomena. I will therefore devote my attention here to research possibilities that can lead toward more definite accounts of languages and phenomena.

One obvious issue to discuss at the very outset are datasets and possible ways of improving them. I have repeatedly discussed research limitations stemming from the differences in datasets, most notably those that are brought about by different strategies and lexicographic solutions that authors of various Slavic dictionaries deploy. To overcome problems of this kind, it would be most useful to develop monolingual and bilingual lexicographic standards, which would lead to normalized data in comparing Slavic languages. It would be incumbent on Slavic studies centers and professional organizations, most notably the International Committee of Slavists (see Committee, 2017), to carry out such work. The benefits of such standards or guidelines would be multifold. They would enable cross-linguistic comparison of Slavic lexical data but, more than that, they would offer a platform for a consistent lexicographic treatment in all Slavic languages. Obviously, guidelines should account for the peculiarities of lexicographic traditions of each individual language. In addition to offering guidelines for lexicographic treatment, the standard should also encompass a standard for data representation (e.g., using the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) scheme, version 5, see Burnard and Bauman, Reference Lou and Bauman2013, or Lexical Markup Framework (LFM); see Francopulo et al., Reference Francopulo, George, Calzolari, Monachini and Bel2007). Thus, for example, the guidelines could specify a consistent manner of stating in loanword dictionaries all languages in the chain of borrowing (e.g., the language of direct borrowing, further languages of origin). These guidelines should also specify appropriate descriptions for the language of direct, first indirect, second indirect, etc. etymology in the chosen data-representation standard.

The next possible contribution to creating more useful datasets could involve solutions that would normalize the existing anisomorphic data. The aforementioned guidelines could be useful to authors of future dictionaries. However, a wealth of data exists in various monolingual and bilingual Slavic dictionaries that needs to be normalized in order to make datasets for Slavic cross-linguistic research operational. The solutions in this field may include search-and-replace patterns that would appropriately tag the elements of the dictionary entry or extract lexical data from monographs. For example, if a dictionary states the language of direct borrowing using an angular bracket and the abbreviation for that language, e.g., [lat., the search-and-replace pattern would look for this sequence and replace it with an appropriate tag, e.g. <etym type=borrowing><lang n=1>lat.</lang></etym>, etc.

I will now address the possibilities for further research that the proposed epistemological construct offers. Two general research directions offer particularly strong opportunities for the elucidation of lexical layers of cultural identity: lexical-cultural language profiles and in-depth contrastive studies. I will discuss them in turn.

Lexical-cultural language profiles offer the possibility of incorporating material from the rich body of literature of the dominant approaches to language and culture (most notably from linguistic culturology) into a broader and more systematic account of the lexical aspects of cultural identity. These profiles for each language and for their variants would specify general lexical ingredients that culturally determine the speakers of the given language or variant and the areas of variation between the speakers. Some of the features are overwhelmingly present in virtually all speakers, while others feature significant variation. To take an example of deep-layer carving of the conceptual sphere, in Slavic languages the lack of the distinction between arm and hand, leg and foot, finger and toe, etc. will almost universally be one of the profilers of cultural identity. On the other hand, the adjectives that describe different food items that have gone bad will be used with enormous variation – some speakers will use the equivalent of bad for all of them, while others will use specific designations such as stale bread, sour milk, rancid butter, etc. However, even in the latter case, the speakers will be culturally profiled by having a potential to use more specific terms. Potential is there even for those who have not mastered those adjectives, as they have a theoretical possibility to eventually master them. Similarly, the exchange layer may feature some sources of origin that generally define all speakers of the same language (e.g., Greco-Latin borrowings in all Slavic languages, which define the speakers as those from the European cultural circle), whereas other sources may exhibit strong geographical variation. Thus, Near Eastern loanwords not only profile Serbo-Croatian as similar to Bulgarian and Macedonian and distant from most other Slavic languages, but also mark a territorial identity of the speakers from the regions that had the longest periods of Ottoman Turkish rule (especially Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Southern Serbia). These speakers are likely to know and use more of these words than those in other areas where the same standard language is used. In the surface layer, common to practically all speakers is the need to participate in negotiating standard language lexicon with elites (paying no attention to elites may even be a negotiation strategy). What varies from speaker to speaker are the kinds of attitudes they may have and what their level of compliance with the lexical norms is. In building lexical profiles, one could concentrate on more stable areas with less variation among the speakers, but then also list the areas with more variation which contribute somewhat less to their general cultural profile.

In-depth contrastive studies offer the possibility to focus on specific subject-matter fields in the deep and exchange layer and concrete norming maneuvers in the surface layer. Looking, for example, at fields such as common flora and fauna to examine the ratio of an inherited, a borrowed, and an engineered lexicon can reveal not only the differences stemming from the different environments of each Slavic language, but also differences stemming from cultural influences and geographical contacts. Similarly, if we look at the legal terminology in general use, we may be able to discover language-specific mental images and distinctions as well as those that are widespread in the Slavic realm and beyond it.

Another interesting field of research may be the relative availability of multiple equivalents. To exemplify this, I conducted a brief survey among the members of the Facebook group Naš jezik (devoted to Serbo-Croatian, with over 11,000 members in May of 2018, mostly from Belgrade, Serbia). I asked a question about the three Serbo-Croatian equivalents of the English word ‘uncle’: ujak ‘one’s mother’s brother’, stric ‘one’s father’s brother’, and tetak ‘one’s mother’s or father’s sister’s husband’. The question was formulated as follows. When I hear the word дядя, Onkel, oncle, tio, tío, uncle,Footnote 1 I think about: a. ujak, b. stric, c. tetak. Words before uncle were the same term in Russian, German, French, Portuguese, and Spanish, respectively. The survey was performed on February 18 and 19, 2018, and the respondents preponderantly chose ‘one’s mother’s brother’ (ujak 117 respondents – 91%, stric 9 respondents – 7%, tetak 2 respondents – 2%). Conducting research on the availability of lexical items from a broader and consistent dataset may reveal interesting facts. In this particular case, the three words for ‘uncle’ have the same frequency and they are similar phonologically and morphosyntactically. One possible explanation of this preponderance of responses selecting the word for ‘one’s mother’s brother’ may be a hypothesis about a higher prominence of mother (who in a traditional family tends to home and children) – hence the choice of something that comes from the maternal side. To confirm it, one would need to select a whole lexical field and see if this factor is equally present in it.

I have already shown in Chapter 11 how the micro maneuver of using normative and cryptonormative labels can be studied in major Slavic monolingual dictionaries. Similar microanalyses can be done for macro maneuvers of enforcing the use of the standard lexicon and their micro maneuvers of stigmatizing lexical errors, giving normative advice. While all these may be present in all Slavic standard languages and their ethnic variants, the manner of their implementation may be very different, contributing thus to the cultural identity of each particular language in question. It seems that two grand ideological concepts play a pivotal role in these macro maneuvers: authority (using the tripartite model proposed by Weber, Reference Weber1919) and nationalism (using the model initially proposed by Gellner, Reference Gellner1983). In particular, to use the three Weberian types of authority, while the authors of macro maneuvers always try to justify their authority as rational-legal, the facts on the ground may be different. It is hence interesting to see the extent to which these macro maneuvers rely on traditional authority (purist maneuvers seem to follow this pattern) and charismatic authority (especially in the various declarations of language councils, academies of sciences, and media appearances of prominent linguists). It is equally interesting to see, from a diachronic perspective, how much linguistic macro maneuvers have contributed to the formation of nations (using the aforementioned Gellnerian model of nation formation and the Brubakerian model of ethnicity).

An interesting possibility of diachronic research has been opened up by Vendina (Reference Vendina2002) in her analysis of Old Church Slavonic as an expression of medieval mentality. Indeed, in each of the three layers the parameters change with the flow of time and an analysis of the lexicon of a distinct historical period may bring about insights into the cultural identity of that particular period in time. A related analysis may concern stability and change in time. Some of the parameters of cultural profiles are most resilient, others change abruptly. An interesting question is what contributes to resilience and what causes changes. Vendina (Reference Vendina2014) announced another important possibility of looking into the distribution of lexemes in different areas of Slavic languages. Her analysis is based on dialectal data, but the same can be done with standard languages, concentrating on those lexemes that contribute to the cultural profiling of various speakers of Slavic languages.

One possible research direction lies in the field of corpus research. The examples throughout this book use lexical frequency in various dictionary datasets. This kind of lexical frequency can be called systemic frequency. Words and their forms also feature textual frequency, the frequency with which they are used in the texts of their language. To use a known example, the lexical class of prepositions constitutes a rather modest proportion of the lexicon, but they are very prominent in the corpora of any language. For example, in Russian (according to Ljaševskaja and Šarov, Reference Ljaševskaja and Šarov2009) there are 18 prepositions in the top 100 words and 4 of them are in the top 10 in this particular Russian corpus, which is certainly considerably more than their percentage in the lexicon. One possibility to expand the research proposed in the present monograph is to compare Slavic corpus data. Some of those data have already been included in the present research by using frequency data to come up with consistent lexical datasets in Chapter 4, but existing corpora of various languages enable the expansion of the current research. However, one should insert a word of caution here. Corpus datasets are considerably more problematic than their dictionary counterparts. Dictionaries might not perfectly represent the lexicon, but corpora are notorious in the variation of numerous criteria that can influence research. Take, for example, negative and positive characterizations of people, an example used in Chapter 5. The ratio of negative and positive characterizations will be drastically different if a newspaper corpus contains readers’ comments. In that case the number of negative characterizations will generally be higher. If no readers’ comments are present, then there is a lower number of negative characterizations, as the journalists are typically more guarded with such characterizations than the authors of the comments. This does not mean that corpus research on the lexical layers of cultural identity is impossible; it only requires sophisticated mechanisms for addressing the possible effects of non-representativeness. These mechanisms are certainly much more demanding than those deployed here for dictionary datasets.

In the concrete contexts of Slavic languages, most of them have relatively reliable corpora, and in some cases (e.g., with the Russian National Corpus, www.ruscorpora.ru) lexically and semantically tagged data and filtering tools enable quite sophisticated queries.

Using subjective frequency in addition to lexical frequency, addressed throughout the present monograph, and corpus frequency, a proposed area of expansion, may be a further area of meaningful data analysis. The speakers’ subjective feeling of the frequency of some group of words (e.g., those stemming from a maneuver in the surface layer) may be not only indicative of their attitude but also decisive in their constant negotiation with linguistic elites.

I have already noted in Chapter 12 that attitudes, with their intensity, centrality, affective, cognitive, and behavioral components, represent an intricate cognitive construct and require fine-tuning of the research tools proposed here. This offers a distinct opportunity for interdisciplinary research with psychologists in conducting large-scale sophisticated surveys of all these attitude components and aspects. A further research prospect lies in the application of the models of attitude change to the study of lexical engineering and refereeing maneuvers. In that light, the maneuvers would be seen as effective or ineffective mechanisms of attitude change.

To put it succinctly, the epistemological construct of the three lexical layers of cultural identity proposed in the present book offers the possibility to conduct in-depth analyses and to create general cultural profiles in a systematic and comprehensive manner, and thus to utilize the wealth of data that is available in various dictionaries and monographs.

Throughout the present monograph, I use examples from Slavic languages, which, as noted in the Foreword, offer ample material on lexical changes and various parameters of all three layers. However, this does not mean that the kind of analysis proposed here is restricted to those languages. In this sense, one distinct possibility lies in applying the research techniques demonstrated here (that are meant to be universally deployable) to the material of other languages. Obviously, some modifications will be needed in each group of languages and each contrasted language pair, but the general parameters should be useful in analyzing any standard language.

A further possibility may lie in the study of the cultures of urban and rural dialects or languages that have not been standardized. In such research expansion, the deep and the exchange layer would principally be used. There may also be cases of languages in the process of standardization where only some segments of the surface layer could be explored (for example, the cases of micro-languages where we only have the maneuvers of linguistic elites and the general body of speakers that remain unaware or uninterested in those maneuvers).

What I hope to have achieved here is the initiation of a new, more consistent, manner of exploring lexical layers of cultural identity. The proof of the pudding will be in potential research stemming from this first step and using the proposed methodology, modifying it where necessary, to produce an armamentarium for tackling the elusive links between language, culture, and identity.