Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Part I Shaping a Legacy

- Part II Rights and Remedies

- Part III Structuralism

- Part IV The Jurist

- 13 Reflections on the Confirmation Journey of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Summer 1993

- 14 Justice Ginsburg

- 15 Oral Argument as a Bridge between the Briefs and the Court’s Opinion

- 16 Fire and Ice

- Coda

- Notes

- Index

15 - Oral Argument as a Bridge between the Briefs and the Court’s Opinion

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2015

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Part I Shaping a Legacy

- Part II Rights and Remedies

- Part III Structuralism

- Part IV The Jurist

- 13 Reflections on the Confirmation Journey of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Summer 1993

- 14 Justice Ginsburg

- 15 Oral Argument as a Bridge between the Briefs and the Court’s Opinion

- 16 Fire and Ice

- Coda

- Notes

- Index

Summary

A Supreme Court oral argument is an odd beast. Unlike at many other courts, in which oral argument represents the one time in which overworked judges can really focus on the issue, facts, and arguments of the parties, oral argument at the Supreme Court is not particularly important to the case’s outcome. The reasons are many. The Supreme Court’s docket is small – around eighty cases heard a year – allowing the justices the luxury of being able to focus deeply on each case. Each justice has four clerks, often among the brightest legal minds of their ages, to assist. The Court tends to restrict the issues presented to those that, in the main, involve broad legal principles rather than intricate factual disputes that tend to get cumbersome in briefs.

By the time issues reach the Supreme Court, they have been through two rounds of judicial decision, helping clarify and crystallize the issue. And, at the Supreme Court, the issues get not one but two rounds of briefing (one at the cert stage and one at the merits stage), plus a plethora of amicus filings, all written by an increasingly specialized Supreme Court bar.

Finally, because the justices vote on a case within one or two days after the oral argument (for Monday and Tuesday arguments, the vote occurs on Wednesday; for Wednesday arguments, the vote occurs on Friday), the justices tend to be prepared for the vote before argument. The end result of all this is that by the time the case reaches oral argument, the justices have had the best preparation possible, and they have devoted signii cant and deep thought to the issue. Oral argument rarely changes which side wins or loses.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

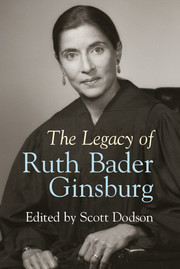

- The Legacy of Ruth Bader Ginsburg , pp. 217 - 221Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2015