Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations

- Part One Into the Dark

- Part Two Redemption

- Part Three Aftermath

- 13 UNESCO: At the Conscience of the World

- 14 The Eau Vive Affair

- 15 Sebastian

- 16 Matthias

- 17 Child Guide

- 18 New York: “St. John the Psychiatrist”

- 19 Hallucinations

- 20 “Dying We Live”

- Appendix John Thompson's Writings

- Notes

- Sources

- Index

20 - “Dying We Live”

from Part Three - Aftermath

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 September 2012

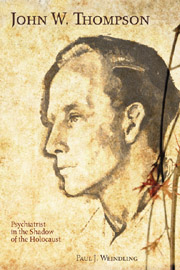

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations

- Part One Into the Dark

- Part Two Redemption

- Part Three Aftermath

- 13 UNESCO: At the Conscience of the World

- 14 The Eau Vive Affair

- 15 Sebastian

- 16 Matthias

- 17 Child Guide

- 18 New York: “St. John the Psychiatrist”

- 19 Hallucinations

- 20 “Dying We Live”

- Appendix John Thompson's Writings

- Notes

- Sources

- Index

Summary

Growing Old

Thompson looked forward to death as “immersion in the sea, absorbed by the infinity of being.” His wartime sense of existing amid death was indelible. In April 1948, he had asked his sister, Margaret, to think kindly of him “if we do not meet again.” He confided to Sebastian in May 1954 that he hoped to avoid a lingering death: “There is nothing partial either in the crucifixion or the resurrection. … May we live or die but not partially be alive and partially be dead.”

Thompson convinced Père Thomas that the fear of death remained half conscious and unexplained, like an abscess beneath the surface of consciousness. At the Hallucinations Seminar of March 1965, Thompson discussed how in the case of Macbeth, “confusion and unreality fuse as his breakdown becomes complete, ending with depression and virtual suicide.” In April 1965, he spoke of living and dying as a primal dilemma. When we visit someone in hospital we might say, “He is dying,” but be thinking, “He is dying and I am living.” This protects us from the frightening fact that “I am living and I am dying.” Thompson similarly reflected to Yosef Yerushalmi, “Why do we say, we are living when we really mean we are dying?” The insight reflected T. S. Eliot's “Life is death.”

A card in Thompson's wallet had Cardinal John Henry Newman's calming reflection that when

the fever of life is over and our work is done then in His mercy may He give us a safe lodging—and a holy rest and peace at last.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- John W. ThompsonPsychiatrist in the Shadow of the Holocaust, pp. 321 - 332Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2010