In a decade of global depression, there were few brighter stars in India than the Hindi poet Harivansh Rai Bachchan, a young Allahabad University professor whose epic poem had catapulted him to stardom. Madhushala, a lyrical retelling of Omar Khayyam’s Rubaiyat, had offered romance to north Indian audiences eager for distraction as the nationalist movement staggered forward, and the poet’s readings packed lecture halls across north India.

Yet war had changed Bachchan no less than it had changed India itself: it was impossible to write of ardor when famine had ravaged the country. Three and a half million Bengalis had died needlessly of hunger, and in his 1946 Bengal ka Kal, “The Bengal Famine,” Bachchan had traded love for insurrectionary fervor. “Be rid of complacency,” he urged India’s starving, likening hunger to the ferocity of Durga, Bengal’s most revered goddess. “Raise the call of dissatisfaction, and sound the cry of revolution.”Footnote 1

Hunger, Bachchan insisted, offered a transformative power largely unrealized by Bengal’s decimated peasantry, who had streamed into Calcutta from the hinterlands three years prior. Dying on the pavement next to regal hotels, Bengal’s “hunger marchers” had come to empire’s second city to stage a feeble protest against imperial rapaciousness. Few Bengalis believed the British officials who blamed the famine deaths on flood, cyclone, and drought. When rice rotted in warehouses, and left on freighters destined for British soldiers overseas, it was hard to see the famine as the consequence of anything but an odious political arrangement borne on the backs of Bengal’s rural poor. A professor of English at the University of Calcutta watched in horror as peasants collapsed next to Gothic colonnades and Art Deco cinemas, vowing that no one who had watched them would ever forget their shameful deaths.Footnote 2 “Hunger marchers confronted those who had made them hungry and had made them march,” Humayun Kabir would write a year later. Their cries “rent the sky and at last penetrated the complacency of the masters who toiled under the self-imposed task of doling out freedom and democracy to the colored peoples of the world.”

As those colonial masters debated how to staunch the political damage wrought by famine, a cloud of rage had settled over the green lawns of Cambridge’s Trinity College. Since the 1890s, expatriate students had met there to debate the future of their homeland, and Indian leaders of all persuasion courted support in the rooms abutting the Great Court. Separated by 8000 miles, news nonetheless galloped from Calcutta to Cambridge: well before the famine had appeared in the Times of London, it was being debated and decried by Cambridge’s Indian students.

Late in 1943, it was these students who produced a slim pamphlet on Bengal authored by Jyoti Basu, a Communist firebrand then studying law in London, and who would later serve as West Bengal’s Chief Minister.Footnote 3 The Man-Made Famine recounted stories of starving Bengalis “sharing food with the animals in the gutter,” fleeing from British troops who shot at hungry crowds and retreated to feast in well-appointed hotels. Basu did not dwell upon the less flattering aspects of the Communist Party’s complicity in British misrule: the Muslim League government in Bengal had been a great deal more effective in organizing famine relief than the Party, which touted radical food committees but had collaborated extensively with the British administration. But his key assertion was one that Harivansh Rai Bachchan, Humayun Kabir, and Indians the world over could agree upon: only India’s legitimate leaders, the nationalist Congressmen held in detention for the duration of the war, possessed the stature and vision needed to prevent famine’s recurrence. “The unanimous demand of the Indian people today,” Basu wrote, “is for food and freedom.”

After decades of marches, boycotts, and strikes in protest of the economic consequences of imperial rule, the Bengal famine marked, in Jawaharlal Nehru’s words, “the final judgment on British rule in India.”Footnote 4 As India’s citizens and politicians reflected upon the famine, they saw in it the clearest failure of colonial politics and economics, tying the promise of self-rule to the project of sustenance for every Indian. Famine had long been central to Indian understandings of imperial injustice, but after 1943, the elimination of hunger emerged as a nationalist imperative.

The ascendance of famine to political preeminence did not preclude a proliferation of visions for how the independent Indian state would function. In the years that followed, Indians imagined their nation as a cooperative socialist republic, a country powered by capitalist industry, a loose confederation of self-sustaining villages, or a modernizing polity that would yoke Indians forward from custom and superstition. But their plans converged around the imperative of providing all Indians with sustenance. Nor, of course, did the famine flatten contentious internecine fighting among Indian nationalists of different hues. But if Congress activists continued to hurl invective at Communists for their wartime collaboration, and members of both parties saw the Muslim League as complicit in misadministration and incompetent in delivering relief, these barbs served to underscore the political centrality that the provision of food and the elimination of famine had come to occupy.

Histories of the turbulent decade preceding independence have understated the Bengal famine’s transformative effect on Indian politics and national aspirations. These histories relegate the famine to a gruesome wartime footnote, overlooking the ways in which a provincial atrocity was transformed into a key site for political claim-making. As a result, the 1943 famine has been used more frequently by historians, economists, and political scientists to advance divergent positions over the causes of famines in general. Amartya Sen’s 1981 Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation famously used the Bengal famine to deflate the notion that famines stemmed from an overall shortage of food, focusing instead upon the role of political entitlements; subsequent work has largely affirmed this position.Footnote 5

Some recent accounts have eschewed more granular work on the famine, deploying it primarily as proof of the British leadership’s deliberate mendacity.Footnote 6 But a small number of sophisticated historical treatments have examined the events of the famine with great care. Paul Greenough’s Prosperity and Misery in Modern Bengal: The Famine of 1943–44, published a year after Amartya Sen’s Poverty and Famines, situated the events of the famine against the backdrop of a longer decline in the Bengal peasantry.Footnote 7 More recently, in examining the machinations of starvation and relief more closely and accounting for the violence which beset Bengal in starvation’s wake, Janam Mukherjee’s Hungry Bengal: War, Famine and the End of Empire demonstrates with great elegance how devastation long outlived the famine itself.Footnote 8

In broadly failing to account for how a provincial tragedy came to be seen as a national injustice, historians have also missed how the larger case for self-rule came to be animated by particular material claims. As news of the famine traveled throughout India and the world, Indian journalists, artists, politicians, and planners could articulate, with clarity and force, the need for an independent government which would attend unfailingly to their sustenance. These claims, in time, came to be shared by an even broader swath of India’s citizenry, animating dreams of how free India might best be governed.

Long before independence was assured, the zealous editors of Independent India, true to name, had begun to make plans for freedom. Followers of M.N. Roy, the charismatic expatriate revolutionary who had been a founder of both the Mexican Communist Party and the Communist Party of India, the Bombay-based cadre had published a storm of articles outlining a radical developmental trajectory for the incipient republic. Yet by the middle of 1943, there were no more blueprints: reports of famine filled the pages of the broadsheet, crowding out more forward-looking visions.

The June dispatch of Vasudha Chakravarty, a young female journalist reporting from Bengal, told of horrors far grimmer than those of India’s earlier famines.Footnote 9 The province’s rural areas were an endless graveyard. Men and women were sneaking into neighbors’ plots by cover of night to steal rice and potatoes, meeting death by pistol or fist, while widespread suicides compounded the ravages of starvation and disease. Bengal’s tortured countryside contrasted mightily with the venal scenes of private life in Calcutta, where corrupt British and Indian officials made merry with profiteers and society girls in the city’s leading hotels. “Who is the enemy of the people?” Chakravarty asked as she surveyed the gruesome disparity. “Is it the foreigner? Is it the native? Or is it both? The imperialist, the fascist, the profiteer, the corrupt official – or all together?”

Bengal’s revolutionary fervor had made it the site of an insidious territorial stratagem four decades prior. Lord Curzon, preparing to divide the restive province in two, decried the Bengalis “who like to think themselves a nation, and who dream of a future when the English will have been turned out, and a Bengali Babu will be installed in Government House, Calcutta.”Footnote 10 The ensuing partition of Bengal in 1905, aimed at staunching the province’s mounting political force, had instead inspired an outpouring of Swadeshi protest, infusing the nationalist movement with new techniques of anti-colonial mobilization. The British were forced to rescind the partition in 1911, but the province’s tradition of protest had been sutured to the legacy of divisive communal politics. This fractious political landscape meant that even the most astute observers of the famine struggled, at first, to mete out responsibility for the mounting death toll.

Yet few Indians believed the imperial spokesmen in New Delhi and London who blamed the famine on the environmental misfortunes of a stormy delta. And the further gruesome news traveled from Bengal itself, the more Indians and their allies were able to voice what the Famine Inquiry Commission of 1944 would partially affirm and what economists would demonstrate four decades later: that the famine had been both avoidable and manmade.

Bengal’s major political parties – the Muslim League, the Hindu Mahasabha, the Communist Party, and the Indian National Congress – agreed on little. The debate over how much culpability the governing Muslim League bore for the famine remained a vehement one, and the proclamations of Communists were rendered unavoidably suspect by the Party’s wartime collaboration. Yet increasingly, Indian observers agreed with what Jyoti Basu had asserted in Cambridge: that the “real blame [for the famine] rests on the government, and that government is British.”Footnote 11

The charismatic Chief Minister of Bengal at the beginning of the famine, Fazlul Huq, had come to power on a populist and grimly ironic slogan of dal and rice for all. Huq, a former secretary of the Indian National Congress who had helped found the All India Muslim League, had campaigned in 1937 on the promise of an end to inequitable land holdings, eschewing what he saw as divisive communalist rhetoric.Footnote 12 Winning the first provincial elections under the banner of his new Krishak Praja Party – “The Farming Peoples’ Party” – Huq presided over an unstable coalition with the Muslim League before their resignation led to an even shakier alliance with the Hindu Mahasabha.

Yet the thundering of provincial politics in Bengal belied the fact that the preponderance of political power in India rested with the colonial Indian administration. India’s “Governors-General” managed the province from New Delhi, cooled by wooden fans in the sprawling South Block of the Secretariat Building. In Calcutta, shielded by the whitewashed balustrades and Cuban palms of Government House, the Conservative parliamentarian John Herbert oversaw provincial machinations from a velvet divan, before his death from appendicitis saw him replaced by the Australian politician Richard Casey. Clad in wing collars and harlequin insignias, these men presided confidently over the complete collapse of Bengal’s food position.

Burma, by the 1930s the world’s largest rice-exporting territory, had long provided a buffer stock for India and Ceylon. Its wartime fall to the Japanese in the winter of 1941–1942 deprived Bengal of only around 15 percent of its imports, but the panic that ensued was more damning. Landlords and traders who had once loaned grain and cash to poor peasants shuttered their godowns, panicked by the specter of war; those peasants, no less agitated, looted paddy to plant and eat.Footnote 13 These problems were compounded by the abuse of infrastructure: Bengal’s tracks shuddered under the weight of trains ferrying rice to soldiers and industrial workers, and fearful of a Japanese invasion, British officials confiscated boats and bicycles along the coast in a maladroit “denial policy,” oblivious to their role in moving grain.Footnote 14

In Delhi, the central government busied itself with organizational filibuster. In March 1942, the Department of Education, Health, and Lands convened a conference to debate the best ways of encouraging greater wartime production, agreeing on the initiation of a Grow More Food campaign and the formation of a Central Food Advisory Council.Footnote 15 But before that Council met for the first time in August, an exasperated Fazlul Huq had already written to Delhi urging a recognition of the “rice famine in Bengal” – a mention that itself was assuredly too late.Footnote 16 Meanwhile, India’s political landscape was descending into its wartime nadir. Six days after Huq’s letter, the failure of the Cripps Mission to secure Congress’ support for the war effort led to the declaration of a “Quit India” movement. Within hours of issuing their demand that the British leave India immediately, nearly 60,000 Congress leaders and activists had been arrested, many remaining in detention until the war’s end.Footnote 17

The spindly casuarina trees fringing the Bengal coast did little to impede the ferocious cyclone that made landfall near the village of Contai in October 1942. Tens of thousands of residents of Midnapore district died in a region already wracked by political disorder: many of the district’s police stations had been burnt down, and thousands of jailed activists watched the storm from their prison cells. The enterprising civil servant B.R. Sen, later Director-General of the Food and Agriculture Organization, watched the storm from his verandah in Calcutta. Days later, he was surveying the remains of villages which had been washed away in preparation for relief efforts, in defiance of a District Officer who gloated that the unruly province had received what it deserved.Footnote 18 Sen courted the support of groups like the Friends’ Society of Britain and the Ramkrishna Mission to clear corpses and repair embankments. But no relief team could replant the aman [winter] rice crop, washed away by torrential rain; nor could anyone scrape the green paddy of the devastating fungus which grew in the cyclone’s wake. Midnapore, once verdant with rice, was a waterlogged graveyard. Its blight portended miserably for the troubled province.

A week before the end of the year, a group of underground Congress organizers circulated an insurrectionary leaflet across Bengal, urging activists who had stayed out of prison to rise up. “There is famine,” the leaflet’s author declared. “Why are our people – the worker, the peasant, the city-poor – starving or semi-naked or living in horrid conditions? Because the British Administration is so corrupt that there is no equal to it.”Footnote 19 British censors did their best to confiscate flyers like these. Yet they struggled to contain popular outlets like the Hindustan Times, where a January cartoon showed a British “food expert” who had arrived in India promising a solution to Bengal’s food problem. Instead, he was too sidetracked by a massive buffet to notice a swarm of groveling peasants.Footnote 20 If this cartoonist had thoroughly lambasted British officialdom, he would have had nothing more charitable to say about the American propaganda film produced that same season, which showed Calcutta dock workers unloading a feast of dried eggs, canned apples, corned beef hash, Tootsie Rolls, and Schlitz Beer for army canteens.Footnote 21

Hunger was not merely Bengal’s purview. Smaller shortages had pockmarked Malabar and Travancore throughout the war, and relief workers fretted that the scale of Bengal’s deprivation would divert scant resources away from their hungry districts.Footnote 22 A team of Bombay Congress activists who had stayed out of prison likened India’s hunger marchers to those in Milan and Florence said to be protesting in a similar manner: both were fighting against the abuse of foreign fascists.Footnote 23 In each case, the activists proclaimed,

the usurper Government does not care a whit for the hunger stricken stomachs, so long as it is able to carry on its loot of food for its own purposes. But blind as such usurpers are, they do not see the monster of hunger that they themselves have created, and it will not be very long now when this monster takes a jump and crashes upon them with a bang.

Those usurpers were, in fact, watching the monster of hunger with alarm. In January, Calcutta’s municipal government wondered if rationing the city would help staunch the arrival of hunger marchers.Footnote 24 In Delhi, the central government issued lame promises to check prices and facilitate transportation of grains, while reminding provincial governments that food was, ultimately, their concern.Footnote 25 And in London, the War Cabinet belatedly took note of India’s “serious food shortage,” establishing a Department of Food after two centuries of rule.Footnote 26 Yet this shuffling did little to calm matters at home, where, the New Statesman and Nation noted, the British government was facing “an enemy more formidable than Congress – famine.”Footnote 27

Bengal, never quiescent, was a hotbed of political quarreling as much as a scene of ghastly starvation. Calcutta’s streets were lined with corpses and the province’s rice prices were sky-high.Footnote 28 Meanwhile, Fazlul Huq had been hounded from the Chief Ministry, replaced by Khawaja Nazimuddin; a new Muslim League ministry formed in April saw the new famine strategy led by the prominent, and incompetent, politician H.S. Suhrawardy.Footnote 29 As district officers appealed to Suhrawardy to direct grains to famine areas, the new Civil Supplies minister focused doggedly on the hoarding he believed to be responsible for shortages. The raids and invective of his “anti-hoarding” drive, however, simply drove stocks further away from the market. Bengal’s political opposition was livid at Suhrawardy’s unwillingness to declare a famine and thereby invoke the famous famine codes.Footnote 30 And the appointment of the Calcutta tycoon M.A.H. Ispahani, an ardent Muslim League supporter, as the sole dealer of rice in Bengal was proof, if ever there were, that the League would rather repay political patrons than manage a worsening catastrophe.Footnote 31

The political atmosphere was poisonous. Bengal’s Communists, the Krishak Praja Party, and the Hindu Mahasabha assailed the impuissant Muslim League, demanding the release of the detained Congress leadership and the formation of a “unity government” in the name of relief. Yet that term held vastly different meanings for Bengal’s opposition parties.Footnote 32 The Hindu Mahasabha, lacking a robust provincial base, used this call to piggyback on popular support for the Congress; its premier, Shyama Prasad Mookherjee, decried the Muslim League for conspiring with the imperialists to starve Bengal.Footnote 33

India’s Communists emphasized their long connection to India’s kisan [peasant] movements and joined the call for “unity,” even as they had secretly collaborated with the British and worked to oust underground Congress organizers.Footnote 34 And they worked diligently to make capital from the famine in Bengal and in provinces far away. People’s War, an incendiary Party weekly, vexed the censor’s office: the Food and Home Departments launched a coordinated effort to suppress or shutter the paper for “publishing alarmist headlines, and reports and pictures calculated to arouse horror.”Footnote 35 Party workers in Bombay distributed a grisly model speech to commemorate the first anniversary of the Quit India movement.Footnote 36 “Bengal,” they wrote, “the cradle of our National movement, has become one vast graveyard. National disunity has meant millions of deaths; it has meant destitution and famine all round. It is today the only passport of the present regime to rule over our land as it likes.” Party leaders in Punjab, the United Provinces, Bombay and Travancore papered their respective provinces with combustible pamphlets, each variants on the same theme: without “unity,” famine would be the purview of all of India, not merely Bengal.Footnote 37

The further political claim-making was from the province, the more it eschewed internecine squabbles to zero in on the role of empire itself. Even before the extent of Bengal’s misfortunes were fully known, the radical activist Jayaprakash Narayan, who had cut his teeth studying social theory at Berkeley and Iowa, was connecting famine to imperial rule. “The British,” he wrote in a letter to freedom fighters in early 1942, “partly by their incompetence and partly by design, have created [the food] problem, and so long as they are here there is no alternative to starvation. Therefore, the fight for freedom is the real fight for food.”Footnote 38 Veteran Congressman C. Rajagopalachari had urged his party to reconcile with the British for the duration of the war; by 1944, he, too, was declaring that only an immediate transfer of power to “popular leaders” would allow for a solution to the problem of food.Footnote 39 Humayun Kabir, in a second pamphlet on the famine, echoed the call for “a National Government at the Centre and broad-based Governments in the provinces, formed with the support of every important section of political opinion in the country.”Footnote 40 Loyalist Indian representatives in the legislature in Delhi balked at the central government’s insistence that the Bengal famine be discussed without reference to the country’s political situation.Footnote 41 The call for a “unity” government did not enjoy universal appeal. M.N. Roy, whose followers had had continued to chronicle the mounting disaster on the pages of Independent India, declared that no “National Government” could conjure up food without a commitment to complete revolution.Footnote 42 Muslim League leader Muhammad Ali Jinnah decried calls for the party to be stripped of provincial power, but agreed that the central government was criminally wrong in blaming the famine on population growth and natural disaster.Footnote 43 The responsibility, he held, was solely that of the British administration, “incapable of meeting any crisis.”

As news of the famine traveled across India, it stoked the notion that only a free, national government could staunch the damage and prevent a recurrence. That idea traveled back to Calcutta, too, reaching the most stalwart members of Bengali society. Home Ministry officials in Delhi gritted their teeth in frustration as they read the speech of a well-respected jurist who had inaugurated a private relief kitchen in August 1943. Hoarders and profiteers, future Law Minister C.C. Biswas had declared, had little responsibility for the famine when compared with the “stupid and scandalous bungling” of officials in Delhi.Footnote 44

The waterlogged fields of estuarial Bengal are far removed from the Punjab plains, its wheat crop irrigated by five rivers. Both bear little resemblance to the fishing villages of the Malabar coast, or the rainshadowed Coromandel coast which flanks it. They are all worlds apart from the snowpeaked Himalayas, the scorched Thar desert, and the rocky Sindh coast. From craggy fortresses on the Deccan Plateau, four dynasties of potentates presided over the sprawling Vijayanagar domain; further north, from the fertile Gangetic Plain, a dynasty of Central Asian rulers reigned over the Mughal Empire. Beneath them, and other polities, a coterie of agrarian and mercantile regimes vied for control of capital, goods, and people.

Yet over the centuries, these disparate environmental and political regions inched closer towards one another, forging a sense of commonality hewn of political and technological transformation. Historians debate the moment at which inhabitants of far-off regions began to see themselves as part of a shared “India,” and the moment at which nationalists could use the idea of a shared national space to propel the struggle for self-rule.Footnote 45 Yet by the time of the Bengal famine, India was inarguably knit together by a common political struggle, new technologies of communication, and a retinue of transformative ideas. The nation was criss-crossed by telephone wires, telegram cable, and thousands of miles of railroad track. Terrestrial radio waves bounced across the length and breadth of the subcontinent, and for a century or more, a capable postal service had ferried letters from place to place. Markets bound together the country through bonds of commerce, and textbooks chronicled a whiggish national history. And as the twentieth century dawned, new technologies of representation let residents of the subcontinent see other people whom they were coming to see as their countrymen – first in daguerreotype, and then with cheaper and smaller Kodak and Graflex cameras.

The notion that Bengal’s suffering was the concern of Indians in Punjab, or Bombay, or far-off Travancore, was animated by the material and ideological transformations wrought of colonial rule. Similarly, news of the famine and charitable responses from across India and the world furthered the idea that India was a national space with a shared purpose and future, with a tragedy in one region becoming an injury to the nation as a whole. “Whether it is Bengal or Kerala,” the Bombay Sentinel concluded in July 1944, “Frontier or Orissa, Bihar or Bombay, the problem is the same: how to feed the people.”Footnote 46

India’s colonial administration had tried desperately to keep news of the famine from spreading outside of the province, with the exigencies of war making this imperative more urgent.Footnote 47 As early as January 1943, Delhi’s Chief Commissioner had asked editors to err on the side of “circumspection” in their coverage of the food situation.Footnote 48 But it was impossible to conceal the wrenching scenes for long. By summer, the sympathetic British editor of the Calcutta Statesman, Ian Stephens, was festooning his broadsheet with photographs that exasperated the central government: corpses, children with kwashiorkor, and emaciated bodies lining city streets.Footnote 49 As other papers followed suit, Stephens traveled to Delhi armed with a stack of visiting cards, these photographs printed on their obverse.Footnote 50 It could not stop the determined Stephens, but the Censor’s Office buzzed with activity. In early 1944, its representatives arrived at the Calcutta home of Ku Chih-chung, editor of the Yindu Ri Bao. The community newspaper of the city’s 20,000 Chinese residents had reported too explicitly upon the famine, and British officials insisted that the dispatches cease.Footnote 51 Later that year, an antagonized British correspondent in India lamented that his dispatch on the “hungry and dumb millions” of India had reached London with the word “hungry” expunged.Footnote 52

Increasingly, Indians’ determination made the work of the Censor’s Office a waste of good ink. Indians armed with Zenith Clippers and other receivers could tune into the broadcasts on Axis stations excoriating the British for starving Bengal.Footnote 53 Rumors swirled on shortwave that the freedom fighter Subhas Chandra Bose was personally arranging for 100,000 tons of rice to be sent as relief.Footnote 54 In London, a Conservative parliamentarian lamented that the Axis Powers’ lies were being “quickly absorbed by a people with empty stomachs.”Footnote 55 Censorship seemed futile when these politicians, and even the most loyal Indian civil servants, were decrying the central government for suppressing news of Bengal’s lamentable state.Footnote 56

It was not merely that news of the famine was shooting past the censor’s gaze. Indians far from Bengal were tying themselves affectively to the province through their relief efforts. Calcutta’s network of nearly 500 private grain depots and relief kitchens, managed by the Bengal Relief Coordination Committee, was supported by donations from a wide swath of society.Footnote 57 The nationalist physician Bidhan Chandra Roy appealed for aid across “barriers of class, creed, and nationality,” declaring that “for the first time in Bengal’s recent history, men from so many different sections, with such divergent political allegiances, have responded together to the call of humanity.”Footnote 58

Given the political squabbling in Bengal, the unity of these appeals was assuredly overstated. Yet moved by word and picture, Indians responded magnanimously. Volunteers from the student wing of the Communist Party of India traveled to Bengal to open their own relief kitchens.Footnote 59 Women took to the streets of Lahore with collection tins, asking for donations of rings and bangles. The president of Ludhiana’s Sikh Missionary College published a poem in the pages of the daily Akali, asking the people of Punjab to “reduce your intake by a fraction and send it to Bengal.”Footnote 60 Karachi’s merchants banded together to form a Famine Relief Committee, sending thousands of bags of rice, wheat, and cloth to Bengal. “That this disaster should have taken place,” the merchants wrote, “in the present age of civilization with modern quick rail, road and sea communications, and in a country where food could be secured to avert the tragedy, is deplorable, and one which does little credit to the administration.”Footnote 61 The young socialist mayor of Bombay, M.R. Masani, who had earlier authored a popular pamphlet on India’s food problem, spoke at a fund-raiser for the All-Bengal Flood and Famine Relief Committee.Footnote 62 From Poona, the Servants of India Society deputed relief workers to Bengal, who provided rice, milk, cloth, and medicine in famine-stricken districts.Footnote 63 The Hindustan Times announced the formation of a relief fund, soliciting donations from its readers and from those of its Hindi-language counterpart, Hindustan.Footnote 64 Perhaps the most remarkable response came from Nairobi, where members of the East African Indian National Congress collected half a million shillings from Indians in Kenya and Tanganyika.Footnote 65 With their second donation of £40,000, the Congress’ assistant treasurer added his hope “that we Indians, who have adopted this part of the world as our home, have not forgotten the mother country.”Footnote 66

Long before the famine claimed its final victim – deaths from smallpox, cholera, and malaria continued well into 1946, and violence poxed the province well into partition – Indian journalists, academics, and artists clamored to Bengal to bear witness to the spectral scene. Pioneering statistician P.C. Mahalanobis, then a professor at Presidency College, would later chart a course for independent India’s development as an influential member of its Planning Commission. But in a grizzly season, he held fast to his disciplinary moorings: numbers mattered, he believed, and a full accounting of the horrors in Bengal would require statistical precision. Strolling past the silk cotton trees outside his office in Baker Laboratory, Mahalanobis set out for the province’s districts in 1944 to calculate the demographic particulars of the mounting death toll.Footnote 67

Educated in Cambridge and London, elite nationalists and privileged expatriates often embarked upon national pilgrimages upon their return.Footnote 68 Arriving from South Africa in 1915, Mohandas Gandhi toured India at the advice of his mentor, Gopal Krishna Gokhale, who urged the activist to see the country’s hinterlands with “his ears open but his mouth shut.” Jawaharlal Nehru had returned to India three years prior. Raised in urban opulence, he had not so much as seen an Indian village; in 1920, the future Prime Minister’s “wanderings among the kisans” showed him both the suffering and the resilience of the Indian peasantry. In a similar manner, the pilgrimages of India’s Anglophone journalists to a hungry province helped tie famine victims and readers together across provincial boundaries. Accounts of districts blighted by corruption were marshaled as the grim evidence of misrule, and proof that a better society could only be ushered in by a representative national government.

Women journalists fueled by professional daring and revolutionary fervor took the lead in producing these accounts. Vasudha Chakravarty had delivered early reports on the plight of Bengal for Independent India; soon, a cadre of left-leaning women took up the charge in longer missives. Kalyani Bhattacharjee’s 1944 War against the People: A Sharp Analysis of the Causes of Famine in Bengal, among the first.Footnote 69 Bhattacharjee had assumed the radical mantle of a sister imprisoned after attempting to shoot the Governor of Bengal years prior; in the famine, she presided over a major women-staffed relief group, the Chattri Sangha.Footnote 70 War against the People narrated the onset of the famine and skewered the complicity of India’s Communists: a cartoon accompanying the short book depicted Party chair P.C. Joshi pouring Bengal’s blood into a chalice held by a British officer. Yet Bhattacharjee reserved her greatest ire for the imperialists themselves. “The dead men, women and children of Bengal,” she proclaimed, “make short work of the so-called democratic fairy tales of Churchill and Roosevelt.”

That same year, Ela Sen’s Darkening Days: Being a Narrative of Famine-Stricken Bengal, focused on the particular suffering of women during the famine, telling grizzly tales of girls sold to brothels with the hope of at least some food.Footnote 71 The young Bengali artist Zainul Abedin lent his famine sketches to the volume, and as Sen cast the famine as the obvious consequence of imperial rule, she pleaded for a reanimated national leadership that would “knit the hungry millions into one strong force that will demand of a corrupt government the death penalty for the hoarder, proper rationing and price control, and considerate planning to safeguard the future.”

These women’s accounts dovetailed with those produced by men who were also traveling through the blighted province.Footnote 72 Most prominent among them was T.G. Narayan, a veteran journalist with the Hindu who traveled from Madras to Calcutta and then to the “human misery” of the Bengal hinterlands.Footnote 73 Strolling through Calcutta’s Maidan at the end of his pilgrimage, Narayan contrasted the peaceful green and the imposing Victoria Memorial with the graveyard that Bengal’s districts had become. “The same crew, who had fouled [Bengal] against the shoals,” he wrote, were “still on the bridge.” The future was uncertain, but he knew that “the problem of famine [has] resolved itself finally into the power to order the destinies of the country.” So long as Indians continued to be “denied the power to arrange our own affairs in a democratic manner,” he concluded, “so long there would recur preventible economic disasters resulting in indescribable human wretchedness.”

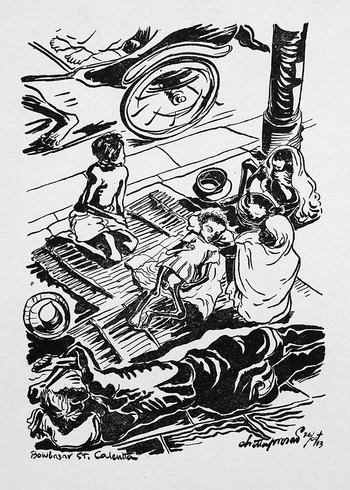

Poetic and visual accounts were essential in linking human suffering to the imperative of political transformation. By the mid 1940s, Sunil Janah was India’s most celebrated photographer; a close friend of P.C. Joshi, he had become the photo editor for People’s Age, the Communist Party daily, in 1943. Armed with a cheap Kodak Brownie and a ream of film, Janah had borne witness to the famine alongside cartoonist and fellow Communist Chittaprosad Bhattacharya; their photos and cartoons were printed in People’s Age and distributed as postcards to raise funds for relief.Footnote 74

Figure 2 The artist Chittaprosad Bhattacharya published his account of a voyage to famine-ravaged Midnapur district in November 1943 as Hungry Bengal, illustrating it with his harrowing sketches. Here, he depicts “the five corpses that I counted one morning in the short stretch of road.”

Words on vellum and newsprint were no less powerful. The Bengali poet Kazi Nazrul Islam accused the imperialists of snatching “the morsel of food from thirty-three crores of mouths. Let their destruction be announced in letters written with my blood.”Footnote 75 Hemango Biswas, a fellow Bengali bard, urged the Congress and League to unite to “expel these traitors from our land” in the name of ending famine.Footnote 76 Short stories and novels chronicled the ravaging of the province: Manik Bandyopadhyay wondered, in Chiniye Khayeni Keno, why Bengalis did not simply loot, concluding they were too depleted to do the same. In Manwantar, Tarasankar Bandyopadhyay imagined a free India where those responsible for famine would meet swift ends. Gopal Haldar’s Terasa Pancasa portrayed a corrupt government eager to profiteer and willfully ignorant of the famine’s toll.Footnote 77

Writers and poets far from Bengal deployed the famine to exemplify India’s woeful decline. Urdu poet Jigar Moradabadi, writing from his home village near Lucknow, was “far away, yet haunted by / cow dust time, the moonrise and dawns of Bengal / I can see them all: those who are dying.”Footnote 78 Maithili writer Nagarjun imagined a grinding stone in Bengal so desolate that “for days and days, the rats, too, were miserable.”Footnote 79 Kannada-language novelist R.S. Mugali linked the Bengal famine with other shortages in his novel Anna.Footnote 80 So many Progressive Writers had written on the famine that the young Urdu writer Ibrahim Jalees was able to assemble a major compilation of stories and poems in the aftermath of the movement’s meeting in Hyderabad.Footnote 81

For many Indian citizens, however, news of the famine came through film. K.A. Abbas would later become one of India’s most celebrated directors and writers, known for his radical bent. But at the time of the famine, Abbas was not yet thirty, working as a publicist for the Bombay Talkies studio and a columnist for the Bombay Chronicle while trying to sell his first scripts. Unnerved by the news from Bengal, Abbas booked a ticket to Calcutta, aghast from the moment his train pulled up at Howrah station, where “emaciated refugees were sleeping in the shadow of the posh hotels and glittering shops of Chowringhee.”Footnote 82

Chased away by the stench of death, Abbas returned to Calcutta six months later in his new capacity as general secretary of the Indian People’s Theatre Association, eager to see the production of Nabanna – the “New Harvest” – that the left-wing drama group had been staging.Footnote 83 Written by Bengali playwright Bijon Bhattacharya, the production culminated in a skeleton dancing to the wails of a singer that “Bengal was starving.” Abbas brought the production back to Bombay, facilitating its staging in an open green next to the Charni Road train station. “The well-fed Bombay audience just gaped and wondered,” one viewer recalled, “dumb-struck by this phenomenon that had hit Bombay like a tornado.”Footnote 84 He set to work adapting the play for the screen.

The film that Abbas completed became Dharti ke Lal – “Sons of the Soil” – and it told the story a farmer driven to Calcutta during the famine after losing his grain and land to a usurious mahajan.Footnote 85 The farmer arrives in Calcutta alongside thousands of other refugees. The relief kitchens are wracked by communal strife, and families are driven apart by prostitution and crime. Yet hunger, a relief worker assures the farmer, not only crushes spirits but can also raise the people. News of the famine spreads throughout India, and as a chorus of schoolchildren proclaim that “Hindustan is our country,” a new harvest is reaped, bigger than any previous one.

The crew and cast of Dharti ke Lal traveled to Calcutta to film, yet after filming two short streetscapes, the cast was detained and banished from the city by the military police. Returning home, the crew transformed the town of Dhule into the Bengal hinterlands: members of the Khandesh Kisan Sabha played Bengal’s destituted peasants, and Ravi Shankar played sitar for the soundtrack. The film premiered at Bombay’s Shree Sound Studios in 1946 before a second screening in Shimla, timed to coincide with the Cabinet Mission sent to negotiate India’s transition to self-rule. Congressmen and Congresswomen flocked to the film, with the communist journalist Rajani Palme Dutt telling Abbas that the problem of India “would be solved if the twelve old men sitting there in the Viceregal Lodge had only come here to see this film and been confronted with the reality of India.”

Throughout the war and the famine, Indians and sympathetic Britons in England had been drumming up support for self-rule. Indian sentiment was as marked by a fundamental unity of purpose, but nationalist politics were as rancorous in Britain as they were at home. The India League, the Indian Freedom Campaign, the Committee of Indian Congressmen, and Swaraj House all raised separate relief funds for Bengal, even as they came together to emphasize the paramount necessity of a national government in New Delhi.Footnote 86

London’s streets were blanketed with Indian pamphlets. In 1943, Nagendranath Gangulee published a major incendiary tract, India’s Destitute Millions Starving Today – Famine? The physician and nutritional scientist had served dutifully on the Royal Commission on Indian Agriculture, but by the Depression, had signed on to the nationalist cause, and he asked the British public to recognize that only immediate independence would prevent the spread of famine.Footnote 87 V.K. Krishna Menon would later emerge as free India’s most revered, and feared, statesman; as secretary of the India League, he authored a call for Unity with India against Fascism, which characterized the famine as “not just an incident in maladministration but a major crime.”Footnote 88 Rajani Palme Dutt published a plan for post-famine agricultural reconstruction in India, predicated upon the notion that “food for all can only be achieved by the masses of the people of India themselves under the leadership of a Government of their own choice.”Footnote 89 British allies of the Indian cause, from the socialist leader Ben Bradlee to the Labour parliamentarian Reginald Sorensen to the Quaker activist and Gandhi confidant Horace Alexander, all published their own fiery treatises on the plunder of Bengal.Footnote 90

The effort to take stock of the famine in Bengal was assisted by those who had been part of Britain’s own food administration. A new Ministry of Food, its administration cobbled together from the staff of the Food (Defense Plans) Department, had been established in the United Kingdom shortly before the war. The head of the Ministry, Henry French, had overseen the domestic issuance of ration cards and the counting of backyard hens, purchasing sugar and wheat and whale oil for government stores and urging citizens to “serve just enough” and “use what is left.” And in August 1944, Lord Amery, the Conservative Secretary of State for India, called upon French to help exculpate the colonial administration from responsibility for Bengal’s suffering.

The provincial and colonial administration in Bengal had been scrambling to rewrite the story of the famine itself. The Muslim League ministry in Bengal had brought out a polished brochure which asked whether it had, in fact, done “all that was humanly possible to minimize suffering, reduce mortality and restore conditions as nearly approximating to normal as was possible in the extraordinary circumstances.”Footnote 91 Touting its free kitchens, canteens, and orphanages, the brochure’s author assured the reader that, in fact, it had. “Prejudiced critics,” it warned, “shall not talk Bengal into a second famine.” Bengal’s new governor, Richard Casey, took to All India Radio to promise that, until self-rule came, the “government will be concerned with the problem of ensuring that the people of Bengal are fed.”Footnote 92 Yet by bringing Britain’s foremost food expert to India, and asking another senior bureaucrat to chair a major commission on the famine, Lord Amery was inadvertently demonstrating how Bengal had ruptured the imperial status quo ante.

French’s host in India was B.R. Sen, India’s new Director of Food, who had replaced the much-reviled civil servant J.P. Srivastava. Both Sen and Srivastava were members of the Indian Administrative Service, yet while Sen had done his best to procure relief, Srivastava had been lamentably tone-deaf. “Sometimes,” he had mused in the Central Assembly in the midst of the famine, “I wonder whether we devoted sufficient attention in the past to the food problem of the country.”Footnote 93 Traveling with Sen through Punjab, Bengal, and Bombay, French frequently clashed with the press.Footnote 94 In Delhi, he deflected questions about the comparative toll of the war in Britain and India.Footnote 95 At a press conference held in the Punjab Secretariat in Lahore, French grew angry at reporters who ignored his plea to avoid “political” subjects.Footnote 96 He returned to London to present his grim findings at the India Office: India, he declared, stood no chance at becoming self-sufficient in food in anything less than four or five years. The Central Administration had done its best to manage an impossible situation and an obdurate provincial administration, and it bore little responsibility for the deaths in Bengal.Footnote 97 “Food control in the UK,” he sighed, “is child’s play compared with India.”Footnote 98

French’s report drew less attention than the formation that same month of the Famine Inquiry Commission chaired by John Woodhead. The veteran civil servant, a friend of Lord Amery, had a knack for thorny issues: six years prior, he had been placed in charge of a commission to partition Palestine into Jewish and Arab states. In his newest role, Woodhead brought together a Hindu and Muslim representative, the nutrition expert W.R. Aykroyd, and the businessman and former deputy governor of the Reserve Bank of India Manilal Nanavati as representative of the trade. Upon the Commission’s disbanding, Woodhead took it upon himself to destroy its voluminous proceedings of the interviews held in camera; Nanavati surreptitiously saved a copy of the rancorous transcripts. In one characteristic exchange, the secretary of the Calcutta Relief Committee, Jnananjan Niyogi, a longtime Swadeshi activist and Congress organizer, assailed the central government over its “wanton bungling.” Britain could serve no role in the reconstruction of Indian agriculture, he declared. “Can this parental task be taken and performed by a foreign power? Emphatically – No!”Footnote 99

The deliberations recorded in the transcripts that Nanavati stowed away evidence of great sensitivity to the man-made machinations which had helped produce famine. The emergent conclusions evidenced a nuanced reading of food availability and its decline, and set the stage for the careful analyses undertaken decades hence. Yet the political imperatives of the day won out in the published document. Even as the final version of the Famine Enquiry Report, published in April 1945, conceded the failure of New Delhi’s price control policy and transportation efforts, it exonerated the imperial administration from graver wrongdoing; likewise, its estimate of 1.5 million famine deaths was far lower than the number of 3 or 4 million circulating widely at the time.Footnote 100 The nationalist response was indignant. The Calcutta journalist Kali Charan Ghosh, who had covered the famine for the Modern Review, fulminated against the Report’s exculpation of British officialdom, who had cavorted with loyalist princes “when people had been dying in the millions.”Footnote 101

Two months after the publication of the Report the Congress leadership was released from wartime detention. The war in Europe had ended in May; before long, Labour would ascend to power in London in a landslide election. In less than ten days, the luminaries of India’s nationalist struggle would meet in the imposing Viceregal Palace in Shimla in a first effort to negotiate a transfer of power.

Those who had spent the war in prison were to grapple quickly with the dramatic impact of the Bengal famine on Indian notions of just rule. The famine’s victims and Indians across the country, a 1945 Kisan Sabha manifesto asserted, “were thrilled with a new hope when Mahatma Gandhi, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Ballabhai Patel [sic] and Maulana Azad declared on their release that the famine stricken were the uppermost in their mind.”Footnote 102 These leaders were quick to speak after years of silence: K.M. Munshi, later India’s Food Minister, berated those who had “destroyed [India’s] industry, drained away its resources, kept it under-developed, under-nourished, backward,” and who had allowed a final, devastating famine.Footnote 103 “The British officer,” he scowled, “claimed to be the Mabaap [mother-father] of the poor people of India. We have only to look at the result of the Mabaap rule to see what it has done.”

The British claim to just rule and the promotion of welfare through food had advanced haltingly throughout the first decades of the twentieth century. Yet colonial administrators, aware the famine had brought concerns of sustenance to the fore, had scrambled to make a belated case. In July 1943, the Department of Food had assembled a Foodgrains Policy Committee, charging it with devising measures to increase food supplies.Footnote 104 Towards the end of the year, the government had enlisted the help of A.V. Hill, an economist at the Royal Society, to help develop a “food plan for India.”Footnote 105 The Director of Food J.P. Srivastava, cheering these moves as proof of the colonial administration’s good intentions, vowed that New Delhi’s task was now

not only one of feeding four hundred million of our countrymen, but also of providing the supplies to do so for millions of small cultivators and seeing that they pass without being hoarded to the public. Our task is not only to bring food supplies into the open market, but also to make them available quickly to every nook and corner in this vast country which cannot otherwise support itself.Footnote 106

Stung by the belief that the British had starved Bengal, the Departments of Food and Agriculture drafted a new joint policy in 1945. Food would remain a provincial concern, their statement affirmed, but the Departments in Delhi would work to “promote the welfare of the people and to secure a progressive improvement of their standard of living. This includes the responsibility for providing enough food for all, sufficient in quantity and of requisite quality.”Footnote 107 Publicists worked to communicate this new “Policy of Food for All,” even as imperial bureaucrats worried about what they had unleashed by affirming this basic position. “It will be more modest and more realistic,” a concerned official in the Department of Industries and Supplies wrote, “to say that Government intend to do its best, or to aim at providing enough food for all, etc., for that is as much as any Government can possibly say.”Footnote 108

Yet the imperatives of war, the global promise of equitable development, and India’s own wartime struggles had made it hard for any government seeking legitimacy to offer any less. From his second-floor White House study, Franklin Roosevelt had promised an end to “freedom from want” four years prior. The pioneers of modernization theory in the United States and Europe were touting the need to bolster standards of living in the name of containing totalitarianism.Footnote 109 In Québec’s stately Château Frontenac, delegates from thirty-four countries were coming together for the first meeting of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), a team of Indian delegates among them.Footnote 110 An ambitious government brochure published while the FAO conference met linked the Departments of Food and Agriculture’s new joint policy to the new possibilities and paradigms of modernization, planning, and development.Footnote 111 Just as the American government had harnessed collective human energy through the Tennessee Valley Authority, the administration in New Delhi was eager to demonstrate “the extent to which vast scale planning can produce and harvest those bumper crops of necessities and luxuries that spring up from the seeds of organized and controlled human endeavor.”

British administrators had heeded the call of sympathetic Indian voices who had urged them to reform the moral orientation of their rule. At the dawn of the famine, one Indian economist had urged imperial planners to consider the “vast majority of our population [who] rarely drink milk, hardly eat meat or fruits or other expensive though nutritious items of diet.” When the war was over, he declared, “economic planning in India must aim towards better distribution of national wealth.”Footnote 112 Manilal Nanavati, coming off his stint with the Woodhead Commission, wrote that the “debacle” of the famine had proven the need for change in the realm of food. “If freedom from want is going to be the basis of the new economic order after the war,” he wrote, “it is necessary to assure at least a bare minimum to India’s teeming millions.”Footnote 113

Those less beholden to imperial objectives were freer to imagine what the lessons of Bengal held for free India’s planning. The president of the nationalist All India Women’s Conference, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, had urged members to envision what a free India’s food plan might look like. “Only a careful development of its vast untapped wealth,” she urged, “based on an economy designed to meet the needs of the people by a free Indian people’s government, can aspire to overcome this dreadful scourge of perpetual famines.”Footnote 114 An economist in Agra lamented the “absence of planning or control” in British India; agricultural progress could not be similarly hampered after self-rule.Footnote 115 Physicist Meghnad Saha, who had forwarded many plans for national development in the pages of his Science and Culture before the war, now felt that it was impossible to plan “unless we have a Government which has popular support and is composed of leaders in whom the people have confidence.”Footnote 116

The most prominent vision of a free, fed India came from Bombay, where seven industrialists and a lone economist gathered after the famine to draft a plan for India’s economic development after independence. The Bombay Plan, as it came to be known, held that all Indian citizens would need to be guaranteed a daily quantum of 2800 calories. This was the number which underwrote their scheme to boost both industrial and agricultural output, with a priority on the former, since only the increased purchasing power born of industrialization would let Indians acquire the food they so desperately needed.Footnote 117 The Bombay Plan would be debated extensively, but moderate commentators lent it some cautious support. One 1944 book reflecting on the famine, part of a popular series on “contemporary topics,” lauded the Plan as one good option among many being drafted in India which intended to render “the famines of the type of 1944 consigned for ever to the limbo of the past.”Footnote 118

In 1947, the forty-year-old writer Bhabani Bhattacharya published his first novel, an English language account of the famine which had so transformed India’s political landscape. So Many Hungers! skewered the British administration, and the rapaciousness of men like M.A.H. Ispahani, who was caricatured as the venal director of Cheap Rice, Ltd. “This famine,” Bhattacharya’s narrator insists, “this brutal doom, was the fulfillment of alien rule.” He asks his reader to imagine “two million Englishmen dying of hunger that was preventable, and the Government unaffected, uncensored, unrepentant, smug as ever! ‘Quit India!’ cried the two million dead of Bengal.”Footnote 119

In 1942, Indian nationalists had asked the British to quit India. But famine and death unleashed the year afterwards made the case that political declarations alone could not. Bengal would be forever changed by the famine. Its death toll aside, the famine poisoned provincial politics even further. The return of the Muslim League to power in Bengal in 1946 antagonized the opposition: the province’s new Chief Minister was H.S. Suhrawardy, whose famine strategy Hindu Mahasabha members and others considered responsible for millions of deaths.Footnote 120 The party head saw in the famine a warning against the mounting Muslim demand for Pakistan: if a separate Muslim state had existed during the famine, he reasoned, its control of Bengal’s arable land would have killed the whole of the population which had remained.Footnote 121

Yet at a national level, famine had transformed India’s political landscape, underscoring the need for self-rule to Indian citizens far away from its epicenter. Photographs and journalism and the affective bonds of charity tied Indians inextricably to Bengal and made its suffering their own; a provincial atrocity was turned, in the midst of war, into a national case against imperial rule. With the nationalist movement at its apogee, no publicity effort or overdue food scheme could convince disillusioned Indians of the munificence of a bankrupt administration.

Famine was, for Indian planners and citizens, the mandate for fundamental transformation – not merely a transition to self-rule, but the crafting of an economy and a polity that would be fundamentally different in its responsibility to citizens. Jawaharlal Nehru maintained that Bengal’s dead “were vivid, frightful pictures of India as she is, suffering for generations past from a deep-seated organic disease which has eaten into her very vitals.”Footnote 122 Only a fundamental recomposition of India’s body politic would offer a cure. “There are still many people,” the future Prime Minister wrote,

who can think only in terms of political percentages, of weightage, of balancing, of checks, of the preservation of privileged groups, of making new groups privileged, of preventing others from advancing because they themselves are not anxious to, or are incapable of, doing so, of vested interests, of avoiding major social and economic changes, of holding on to the present picture of India with only superficial alterations.

The famine would need to remind citizens, he wrote, of the need to fashion a fundamentally new India, and the Congress leadership seized quickly upon this mandate. In summer 1946, the party’s National Planning Committee met in Bombay to draft up its first plans. A subcommittee comprising Nehru and the economists John Mathai and K.T. Shah affirmed that “the provision of adequate food” would be the item of highest priority in any scheme for post-war development.Footnote 123

In the years surrounding independence, the memory of the famine was sutured to the mandate for a cohesive national government, and fundamental economic change. A popular 1947 Hindi pamphlet on India’s food problem was dedicated to the victims of the Bengal famine: India’s planners and citizens could redeem their deaths by ensuring, through planning, that free India never saw a similar tragedy.Footnote 124 Three years after independence, Kasturba Lalwani, the author of a Hindi text on India’s most pressing economic matters, recalled a foreign administration in New Delhi “snatching grains from the country’s east. Black marketeers and former officials wrested control of the entire nation. The worst type of misbehavior the twentieth century has seen was carried out in the name of ‘civilization.’ And in the midst of that frenzied dance, the country’s people were marked for death like so many pests.”Footnote 125 For her, too, the promise of economic freedom was the promise of an end to famine wrought of foreign exploitation.

The Bengal famine galvanized an India increasingly linked by bonds of economy and affect alike. And it provided to planners and citizens the necessary, if horrific case for a strong, central, and independent government which stood to actualize the promises of economic transformation. The famine brought food to the center of Indian state-making at the moment of its actualization and saddled India’s nationalist leadership with the obligation to succeed where the British had failed. In 1946, a gloomy but undaunted Harivansh Rai Bachchan had asked Indians to remember Bengal as they “realized the strength of hunger / the strength of your own daring and boldness.” A year later, as the Union Jack fell across the country, Indians’ boldness was no longer in question, but the strength of hunger would continue to animate their varied plans and dreams.