Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Introduction: Thirty red pills from Hermes Trismegistus

- Aren't we Living in a Disenchanted World?

- Esotericism, That's for White Folks, Right?

- Surely Modern Art is not Occult? It is Modern!

- Is it True that Secret Societies are Trying to Control the World?

- Numbers are Meant for Counting, Right?

- Wasn't Hermes a Prophet of Christianity who Lived Long Before Christ?

- Weren't Early Christians up Against a Gnostic Religion?

- The Imagination… You Mean Fantasy, Right?

- Weren't Medieval Monks Afraid of Demons?

- What does Popular Fiction have to do with the Occult?

- Isn't Alchemy a Spiritual Tradition?

- Music? What does that have to do with Esotericism?

- Why all that Satanist Stuff in Heavy Metal?

- Religion can't be a Joke, Right?

- Isn't Esotericism Irrational?

- Rejected Knowledge…: So you mean that Esotericists are the Losers of History?

- The Kind of Stuff Madonna Talks about – that's not Real Kabbala, is it?

- Shouldn't Evil Cults that Worship Satan be Illegal?

- Is Occultism a Product of Capitalism?

- Can Superhero Comics Really Transmit Esoteric Knowledge?

- Are Kabbalistic Meditations all about Ecstasy?

- Isn't India the Home of Spiritual Wisdom?

- If People Believe in Magic, isn't that just Because they aren't Educated?

- But what does Esotericism have to do with Sex?

- Is there such a Thing as Islamic Esotericism?

- Doesn't Occultism Lead Straight to Fascism?

- A Man who Never Died, Angels Falling from the Sky…: What is that Enoch Stuff all about?

- Is there any Room for Women in Jewish Kabbalah?

- Surely Born-again Christianity has Nothing to do with Occult Stuff like Alchemy?

- Bibliography

- Contributors to this Volume

- Index of Persons

- Index of Subjects

Religion can't be a Joke, Right?

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 November 2020

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Introduction: Thirty red pills from Hermes Trismegistus

- Aren't we Living in a Disenchanted World?

- Esotericism, That's for White Folks, Right?

- Surely Modern Art is not Occult? It is Modern!

- Is it True that Secret Societies are Trying to Control the World?

- Numbers are Meant for Counting, Right?

- Wasn't Hermes a Prophet of Christianity who Lived Long Before Christ?

- Weren't Early Christians up Against a Gnostic Religion?

- The Imagination… You Mean Fantasy, Right?

- Weren't Medieval Monks Afraid of Demons?

- What does Popular Fiction have to do with the Occult?

- Isn't Alchemy a Spiritual Tradition?

- Music? What does that have to do with Esotericism?

- Why all that Satanist Stuff in Heavy Metal?

- Religion can't be a Joke, Right?

- Isn't Esotericism Irrational?

- Rejected Knowledge…: So you mean that Esotericists are the Losers of History?

- The Kind of Stuff Madonna Talks about – that's not Real Kabbala, is it?

- Shouldn't Evil Cults that Worship Satan be Illegal?

- Is Occultism a Product of Capitalism?

- Can Superhero Comics Really Transmit Esoteric Knowledge?

- Are Kabbalistic Meditations all about Ecstasy?

- Isn't India the Home of Spiritual Wisdom?

- If People Believe in Magic, isn't that just Because they aren't Educated?

- But what does Esotericism have to do with Sex?

- Is there such a Thing as Islamic Esotericism?

- Doesn't Occultism Lead Straight to Fascism?

- A Man who Never Died, Angels Falling from the Sky…: What is that Enoch Stuff all about?

- Is there any Room for Women in Jewish Kabbalah?

- Surely Born-again Christianity has Nothing to do with Occult Stuff like Alchemy?

- Bibliography

- Contributors to this Volume

- Index of Persons

- Index of Subjects

Summary

Laughter has a history all its own. In spite of the prominence of humour across the evolution of our species, though, it is among the least scrutinised spheres of human experience. As Mikhail Bakhtin showed, clowns and fools, like jokes and hoaxes, are dismissed by scholars as either “purely negative satire” or else as “recreational drollery deprived of philosophical content.” In short, humour is not taken seriously. A more complex picture of laughter can be gleaned from the study of post-War American esotericism, and in particular the psychedelic church movement. The extraordinarily rich theology of laughter produced by these outlaw religious fellowships is the subject of this essay.

Dawning in the early 1960s, the ideology of “psychedelicism,” as I call it, was established by a handful of fellowships united in the belief that cannabis, as well as other vision-inducing substances, unlocked the highest spiritual potential of humanity. According to these groups, psychedelics (including LSD, DMT, and mescaline) were not mere drugs, but “sacraments” that worked much in the same way as meditation, yoga, and prayer – albeit far more expediently. In the words of Art Kleps, hailed by Timothy Leary as the Martin Luther of psychedelicism, “[a]cid is not easier than traditional methods, it's just faster, and sneakier.” Not all psychedelic fellowships styled themselves after churches, however. Psychedelicism took on a variety of institutional forms, such as secret brotherhoods, experimental therapy centres, and anarchist conspiracies. Some groups that refused to describe themselves with words like “religion” or “church” did so because they understood the transcendental flash of divine illumination induced by psychedelics to be too sacrosanct to put into words. For groups like the Merry Pranksters, the trappings of religion seemed positively outdated.

Amidst this reverential approach to drugs, humour took on a metaphysical significance. According to the foremost psychedelicist, Timothy Leary, “the entire consciousness movement was dedicated to a playful rather than serious approach: … [T]he essence of consciousness change is humor and gentle satire. It actually gets quite theological.” The theological tradition of psychedelicist humour reached its climax with the Discordian Society, an anarchistic fellowship formed in the mid-1970s, which “disguised” its teachings as an intricate jest.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

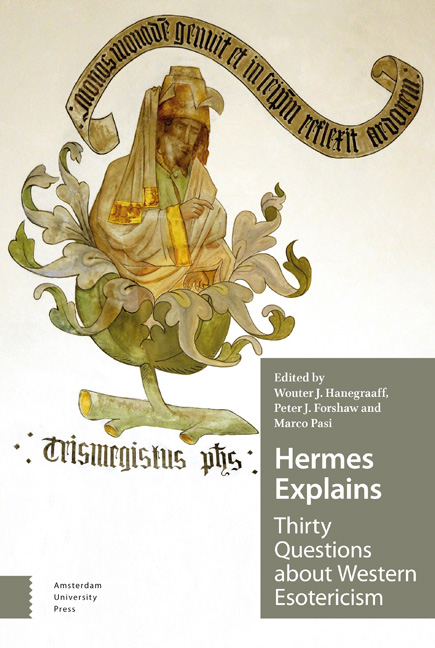

- Hermes ExplainsThirty Questions about Western Esotericism, pp. 127 - 136Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2019