1 Introduction

This chapter seeks to investigate the way in which the system of protection of geographical indications (GI) has developed in the legal, policy, and socio-economic context of an emerging country such as Vietnam. Vietnam has over fifteen years of experience in GI protection, and GIs are considered an important tool for socio-economic development in the country. Vietnam also recently completed the negotiations of two international free trade agreements, which include specific provisions on GIs: one with the European Union, the European Union-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement,Footnote 1 and the other one with twelve countries of the Pacific (including the United States), the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPP).Footnote 2 Our analysis in this chapter aims at providing useful insights on the law and practice of GIs in Vietnam, which could also be relevant with respect to other countries in the region, as several countries in South East Asia are currently considering reforms to their existing laws or are implementing new provisions in the areas of GIs.

First established in 1995 through the system of appellations of origin brought by the French, the Vietnamese legal framework for the protection of GIs provides for a State-driven, top-down management of GIs that is supported by strong public policies. Indeed, beyond the strict legal scope, GIs have recently attracted an increasingly growing interest within the country as a promising tool for ‘socio-economic development … to eliminate hunger and reduce poverty’Footnote 3 and for the preservation of the ‘cultural values and traditional knowledge of the nation’.Footnote 4 Yet despite the political will to promote GIs, the impact of GIs for socio-economic development in Vietnam in practice is facing two challenges. First, the number of registered GIs is still very low compared to that of geographical names registered as trademarks (TMs). Second, the use of the registered GIs on products for sale in Vietnam is still very limited. As this chapter will uncover, the reasons for the limited registration and use of GIs in Vietnam are due to a range of institutional, socio-economic, and organizational factors.

The existing literature, referring to origin labelling as ‘branding from below’Footnote 5 or ‘development from within’,Footnote 6 has embraced GIs as an instrument of socio-economic development owing to the link with the origin. Indeed, while the primary functions of GIs relate to competition rules and market regulation,Footnote 7 a large body of scholarship has built upon the market utility of GIs to claim that they may also contribute to local development by advancing the economic and commercial interests of local farmers, producers, and other stakeholders along the supply chain. In line with the economics of product differentiation,Footnote 8 it is contended that GIs – by exhibiting the very characteristics of a specific terroirFootnote 9 – help producers get out of the ‘commodity trap of numerous similar and undifferentiated products trading primarily on price’.Footnote 10 Pursuant to this, a number of food sociologists have described the emergence of a ‘wider Renaissance of “alternative agro-food networks” and “quality discourse” ’Footnote 11 in which GIs fit in reaction to the hyper-industrialization, mass production, and standardization of ‘placeless’ food, as well as the failure to impose safety criteria, as illustrated by the spread of mad cow disease.Footnote 12

In this context, it has been argued that the successful marketing of a product based on the link between its specific origin and its unique quality, characteristic, or reputationFootnote 13 may allow GI producers to increase their access to new or existing markets, gain a competitive advantage, and make a profit from the product differentiation.Footnote 14 The capturing of price premiums by producers is ‘often one of the first aims of supporting a strategy for an origin-linked product’.Footnote 15 It is further suggested that the economic benefits derived from the successful marketing of GIs may also foster trust, social cohesion, and solidarity since operators need to cooperate and exchange information.Footnote 16 This is particularly true in Europe, where there is a long history of producer-led GI collectives. There, the sui generis system of protected designations of origin and protected geographical indications requires the formation of a producers’ association and a code of practice at the application stage. This arguably fosters collective action and collaboration among local stakeholders.Footnote 17

In contrast, a number of authors have pointed out that in developing and emerging countries, GI initiatives are often driven by outside actors such as the State or development agencies. Hence, not enough GI-related activity, leading to the organization of producers and registration of GIs, is developed at the local level and within local producers.Footnote 18 Yet, as recalled by Biénabe and Marie-Vivien, what makes GIs peculiar and valuable instruments from a social development standpoint is the capacity of GIs to embody the link with the geographical origin where the product’s reputation is built, which accounts for public considerations by the State and national governments, while still retaining private considerations insomuch as GIs are used by private stakeholders to identify products destined to consumers.Footnote 19

However, while the literature holds promises of GIs as tools for socio-economic development, it has been noted that empirical data in this respect are lacking, especially from emerging and developing countries.Footnote 20 In particular, it has been noted that some context-specific factors may facilitate or hinder the ability of GIs to effectively promote such development.Footnote 21 This conclusion seems to be reflected also in the existing empirical research conducted so far. This research has in fact yielded inconclusive results of the effect of GIs on economic development and demonstrated that the impacts of GIs essentially vary on a case-by-case basis.Footnote 22 Even with respect to successful GIs, particularly in Europe, economists such as Belletti and Marescotti have drawn attention to the risk that only the largest processing and distribution firms that sell in international markets or use modern and long marketing channels might capture the additional earnings that can be obtained due to GIs.Footnote 23 Overall, it remains difficult to measure the extent to which the price premium that is commanded often by GI products is directly attributable to the legal protection granted to GIs only or whether other factors can also contribute to such premium, for example, the long-established reputation of certain products or the existence of subsidies and private investments in certain sectors of the economy.Footnote 24 Ultimately, what has emerged as a consensus among researchers is that GI legal protection alone is a necessary but insufficient condition to bring the desired effects.Footnote 25 In this regard, Hughes contends that ‘[t]he argument that substantially stronger GI protection will benefit developing countries simply mistakes the piling up of laws for the piling up of capital investment’.Footnote 26

Yet there is a need for research as to what an enabling legal and institutional GI framework is, or should be, in the context of an emerging country. In addition, it seems that a combination of other enabling factors is required for a GI framework to positively impact socio-economic development.Footnote 27 For example, commentators have pointed to the need for substantial investments in advertising and marketing to develop a product’s image and reputationFootnote 28 as well as to establish quality control, monitoring, and enforcement mechanisms aimed at building consumer trust in the product’s quality.Footnote 29 However, while Albisu cautions that ‘marketing of many OLPs [Origin Labelled Products] is often one of the weakest links in the chain’,Footnote 30 Zografos notes that the costs involved might be considerable for small farmers in developing countries, especially given the low reputation of many GI products.Footnote 31 Notably, the collective action dynamics involved in the GI initiatives, which tie local actors ‘in a lattice of interdependence’,Footnote 32 have also emerged as critical factors for directing their effects.Footnote 33 According to Barjolle and Sylvander, the effectiveness of the collective action depends on the ability of each local actor to ‘appropriate the collective process’Footnote 34 – an act that may be undermined by dominant market positions, local power relations, and supply chain inequalities.Footnote 35 In this regard, Larson stresses the need for an enabling institutional environment and collective organization with strong institutional mechanisms and governance systems.Footnote 36

This chapter offers additional insights on GIs and socio-economic development from the perspective of an emerging country, namely Vietnam. In particular, our study seeks to identify some of the factors that are limiting the use of both the GI registration system and the registered GI labels on the products themselves. In this respect, our chapter seeks to provide useful empirical data that could assist in better understanding the use of GIs in practice in an emerging country in Asia. The chapter proceeds as follows. After a description of the methodology in Section 2, we provide a thorough analysis of the legal and policy framework for the protection of GIs in Vietnam in Section 3. Subsequently, we present two GI case studies – the fried calamari from Hạ Long and the star anise from Lạng Sơn – with a particular focus on the commercial and marketing strategies of these GI initiatives in Section 4, which will lead to our discussion in Section 5.

To conclude, we highlight the following three points: first, despite the increasing number of registered GIs in Vietnam, which is explained by a strong top-down involvement by the State in the identification and registration of GIs, the success of the registration process remains mixed due to the extremely strict criteria for demonstrating the link with the origin. Second, the commercial and marketing aspects have an impact on whether the use of GI labels is promoted or hindered. These factors determine the success of GIs from a socio-economic development perspective; it depends especially on whether it is a domestic or an export-marketing channel, and a processed or raw product. Third, the commercial and marketing channels also influence the negotiation skills of local farmers and producers, which in turn affect the way the GI labels are used in trade, as well as the extent to which they may contribute to building the product’s reputation and fostering local economic development.

2 Methodology

Our methodology in this chapter is primarily qualitative. We used a variety of methods to generate data. First, in order to provide a thorough understanding of the Vietnamese legal and policy framework for GIs, secondary data were generated through the analysis of legal and policy documents, including the Vietnamese Intellectual Property LawFootnote 37 (Vietnam IP Law), its circulars and decrees, and other sources of law such as GI codes of practice. Second, we conducted a number of interviews with officials of the National Office of Intellectual Property (NOIP) and experts on intellectual property law to strengthen our analysis of legal documents. Third, we adopted a comparative case study approach to assess the impact of the commercial and marketing channels, and compared two GI initiatives with contrasting commercial and marketing strategies. This approach led us to study the fried calamari from Hạ Long, which has a very strong local market, and the star anise from Lạng Sơn, which is an export-oriented product. The contrast between these two GI initiatives allows us to analyse whether, and why, different marketing strategies may affect the success of GIs from a socio-economic development perspective.

For the purposes of the two case studies, we collected primary data through a combination of semi-structured interviews with public authorities and stakeholders in the supply chain, including farmers and processors; distributors and traders; and leaders of farmers’ associations and cooperatives. The interviews were conducted in Vietnam between March and May 2014. Overall, we conducted 6–8 semi-structured interviews for each GI product under investigation. Furthermore, official documents relating to the establishment and organization of the GI initiatives, including charters, bylaws, and board regulations, and internal documents, such as meeting reports, project reports, and annual statements collected from the interviewees, have provided valuable information on the operation and management of the GI initiatives under study. Finally, data were also sourced from development projects funded by international agencies in which we had previously been involved.

3 Limited Number of Registrations Despite a Complete Legal and Policy Framework for Geographical Indications in Vietnam

3.1 Demanding Criteria for the Registration of Geographical Indications

The actual sui generis legal framework for protecting geographical names that designate the origin of products in Vietnam was created in 1995 with the introduction of the protection of ‘appellation of origin’ in the Civil Code of Vietnam,Footnote 38 which contained all provisions regarding intellectual property, following a cooperation between France and Vietnam.Footnote 39

According to Article 786 of the Civil Code of Vietnam of 1995, an ‘appellation of origin is a geographical name of a country or locality that is used to indicate the origin of the goods as being in that country or locality, provided that the goods have characteristics or qualities that reflect the specific and advantageous geographical conditions of a natural or human character or the combination of thereof’. Interestingly, the Vietnamese definition does not seem to provide for the combination of ‘human and natural factors’ that could be said is included in the definition of ‘appellation of origin’ as provided by the 1958 Lisbon Agreement for the Protection of Appellation of Origin.Footnote 40 Still, the definition requires proof of a strong link between a product’s quality or characteristics and its origin for the definition of a geographical name to be an ‘appellation of origin’ under the Civil Code.

In 2001, with technical assistance from France, Vietnam registered the first two appellations of origin for Phu Quoc fish sauceFootnote 41 and Moc Chau Shan Tuyet teaFootnote 42 following the definition in the Civil Code.Footnote 43 In January 2007, Vietnam joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) and, as part of the accession process, adopted a new Intellectual Property Law (IP Law) in 2005. In this new IP Law, Vietnam introduced the same definition of GIs as in Article 22 of the Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Agreement).Footnote 44 This definition is partially less strict than the previous definition of appellation of origin under the Vietnam Civil Code of 1995. In particular, Article 79 of the IP Law provides that a GI product must originate from the area, locality, territory, or country corresponding to the related GI and must also have the reputation, quality, or characteristics essentially attributable to the geographical conditions of the area. According to Article 81 of the IP Law, this criterion of reputation is based on consumer trust in the product. However, in practice, the criterion of ‘reputation’, or reputation-based GIs, has not been used on its own so far in Vietnam. Instead, the registration of all forty-nine GIs that are currently registered in Vietnam was granted upon demonstration that the relevant geographical area conferred on the product specific quality and characteristics as defined by one or several qualitative, quantitative, or physical, chemical, microbiological perceptible norms. These characteristics had to have the ability to be tested by technical means or by experts with appropriate testing methods.Footnote 45

Moreover, Article 82 of the IP Law requires that the characteristics of the GI-denominated products that are derived from geographical conditions include both ‘natural factorsFootnote 46 andFootnote 47 human factors’.Footnote 48 This language directly suggests a mandatory combination of human and natural factors to justify GI registration in Vietnam,Footnote 49 which is much stricter than the definition of GIs that is provided in TRIPS regarding the strength of the link between a product and its geographical origin.Footnote 50 Ultimately, it can be said that GIs in Vietnam are still considered ‘appellations of origin’ under the original definition that is provided in the Vietnam Civil Code since the criterion of proving the link between the quality of products and their respective geographical environments must still be met. Evidence of this is the length of the GI dossiers – around twenty pages each – including the demonstration of the link between the products and their geographical origins. As mentioned earlier, so far no GI registration has been issued in Vietnam based on the criterion of reputation alone.

3.2 Type of Products Designated as Registered Geographical Indications in Vietnam

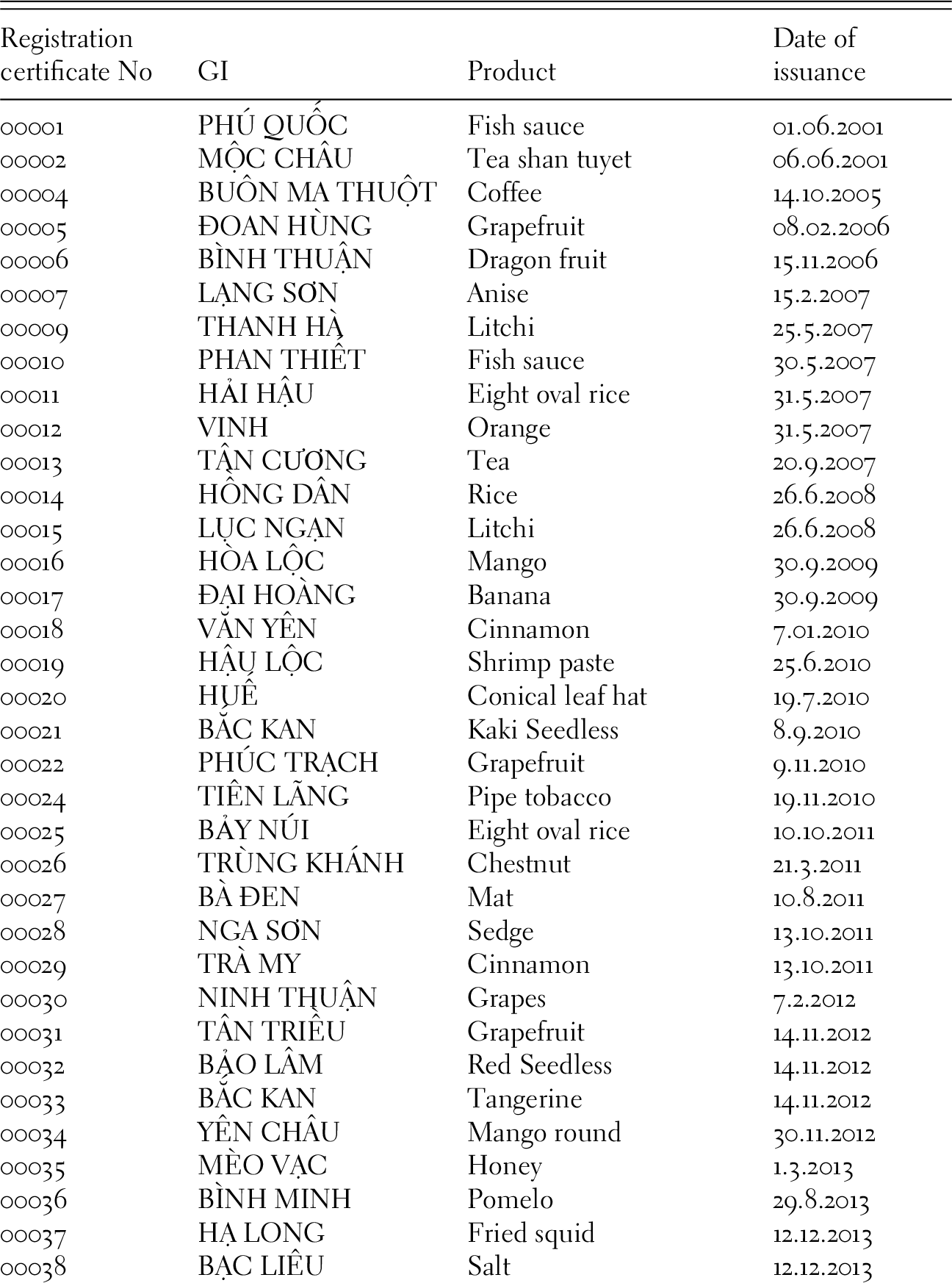

Table 13.1 lists all registered GIs in Vietnam as of March 2017. It lists the GIs and divides them per type of products. As the readers may easily notice, GI-designated products in Vietnam are currently still primarily raw materials, including fruits, vegetables, and materials used in processed products (79 per cent of registered GIs). These materials tend to have low economic value despite the economic and cultural importance for the country of processed products and handicrafts. In turn, this may account for the limited impact of GI protection on socio-economic development in Vietnam.

Table 13.1 List of protected GIs of Vietnam (not included foreign GIs)Footnote 51 as of March 2017

| Registration certificate No | GI | Product | Date of issuance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 00001 | PHÚ QUỐC | Fish sauce | 01.06.2001 |

| 00002 | MỘC CHÂU | Tea shan tuyet | 06.06.2001 |

| 00004 | BUÔN MA THUỘT | Coffee | 14.10.2005 |

| 00005 | ĐOAN HÙNG | Grapefruit | 08.02.2006 |

| 00006 | BÌNH THUẬN | Dragon fruit | 15.11.2006 |

| 00007 | LẠNG SƠN | Anise | 15.2.2007 |

| 00009 | THANH HÀ | Litchi | 25.5.2007 |

| 00010 | PHAN THIẾT | Fish sauce | 30.5.2007 |

| 00011 | HẢI HẬU | Eight oval rice | 31.5.2007 |

| 00012 | VINH | Orange | 31.5.2007 |

| 00013 | TÂN CƯƠNG | Tea | 20.9.2007 |

| 00014 | HỒNG DÂN | Rice | 26.6.2008 |

| 00015 | LỤC NGẠN | Litchi | 26.6.2008 |

| 00016 | HÒA LỘC | Mango | 30.9.2009 |

| 00017 | ĐẠI HOÀNG | Banana | 30.9.2009 |

| 00018 | VĂN YÊN | Cinnamon | 7.01.2010 |

| 00019 | HẬU LỘC | Shrimp paste | 25.6.2010 |

| 00020 | HUẾ | Conical leaf hat | 19.7.2010 |

| 00021 | BẮC KAN | Kaki Seedless | 8.9.2010 |

| 00022 | PHÚC TRẠCH | Grapefruit | 9.11.2010 |

| 00024 | TIÊN LÃNG | Pipe tobacco | 19.11.2010 |

| 00025 | BẢY NÚI | Eight oval rice | 10.10.2011 |

| 00026 | TRÙNG KHÁNH | Chestnut | 21.3.2011 |

| 00027 | BÀ ĐEN | Mat | 10.8.2011 |

| 00028 | NGA SƠN | Sedge | 13.10.2011 |

| 00029 | TRÀ MY | Cinnamon | 13.10.2011 |

| 00030 | NINH THUẬN | Grapes | 7.2.2012 |

| 00031 | TÂN TRIỀU | Grapefruit | 14.11.2012 |

| 00032 | BẢO LÂM | Red Seedless | 14.11.2012 |

| 00033 | BẮC KAN | Tangerine | 14.11.2012 |

| 00034 | YÊN CHÂU | Mango round | 30.11.2012 |

| 00035 | MÈO VẠC | Honey | 1.3.2013 |

| 00036 | BÌNH MINH | Pomelo | 29.8.2013 |

| 00037 | HẠ LONG | Fried squid | 12.12.2013 |

| 00038 | BẠC LIÊU | Salt | 12.12.2013 |

| 00039 | LUẬN VĂN | Grapefruit | 18.12.2013 |

| 00040 | YÊN TỬ | Yellow apricot flowers | 18.12.2013 |

| 00041 | QUẢNG NINH | Ngan (a type of shellfish) | 19.3.2014 |

| 00043 | ĐIỆN BIÊN | Rice | 25.09.2014 |

| 00044 | VĨNH KIM | Fruit milk | 28.10.2014 |

| 00045 | QUẢNG TRỊ | Pepper | 28.10.2014 |

| 00046 | CAO PHONG | Oranges | 5.11.2014 |

| 00047 | VAN DON | Peanut worm | |

| 00048 | LONG KHÁNH | Rambutan fruit | Unknown |

| 00049 | NGỌC LINH | Medicinal herb | Unknown |

| 00050 | VĨNH BẢO | Pipe tobacco | Unknown |

| 00051 | THƯỜNG XUÂN | Cinnamon | Unknown |

| 00052 | HÀ GIANG | Orange | Unknown |

| 00055 | HƯNG YÊN | Longan fruit | Unknown |

3.3 A State-Driven Top-down Registration and Management Process

The governance of GIs in Vietnam is characterized by the State’s top-down registration and management process. In particular, Vietnam’s GI system is characterized by the division of rights between (a) the right to own the GI; (b) the right to register the GI, which means the right to decide on the content of the code of practices, including the geographical area; (c) the right to manage the GI, which relates to managing the granting of the right of use and of control procedures; and (d) the right to use the GI.

Some of those rights can be delegated to others as shown below:

(a) In Vietnam, geographical indications are owned by the State.Footnote 52 Therefore, this ownership cannot be transferred as GIs are considered a part of Vietnam’s national heritage.

(b) The State, as owner of GIs, has the right to register GIs. This right may be delegated to

– producers, organizations, and individuals;

– collective organizations representing individuals; or

– administrative authorities of the locality.

(c) As the owner, the State has the right to manage GIs. It may delegate this right toFootnote 53

– the People’s Committee of the province or city where the product comes from;

– any agency or organization assigned by the People’s Committee of provinces and cities if it represents all organizations and individuals using the GIs, and if that agency or organization represents all other organizations or individuals granted with the right to use geographical indications.Footnote 54

(d) Producers have the right to use the GI,Footnote 55 including organizations and individuals authorized by the managing authority (point (c) above).

In practice, GIs are always registered by local authorities, such as the provincial Departments of Science and Technology (DOST), or People Committees (PC) of provinces, districts, or cities.Footnote 56 Even though they are legally permitted, no applications or registrations of GIs are made by producers or collective organizations representing individuals.Footnote 57 Once the GI is registered by the relevant authority, the latter promulgates a regulation for its management, where either the same authority or a different one (either a sub-department or a sub-region) is designated to manage the GI. In very rare cases (such as the conical hat from Hué GI),Footnote 58 the management agency is not a public authority but an association (the Women’s Union).Footnote 59

Legal use of GIs has been slow, with many GIs completing the ‘experimental period’ of the distribution and use of stickers and labels on the packaging of the products. For example, in the case of the GI Moc Chau Shan Tuyet Tea,Footnote 60 the association of producers launched a special packaging with the name of the GI. Additionally, in the case of the Nuoc Mam Phu Quoc fish sauce,Footnote 61 no fewer than eighty-three out of eighty-six producers are members of the association, among whom sixty-six have been granted the right to use the GI, but only eight are actually using the GI label.Footnote 62

As we elaborate below, for example, with respect to one of the case studies below (the Lang Son star anise GI),Footnote 63 the management of GIs also includes quality-control activities, which are supposed to be carried out by STAMEQ (Standards, Metrology, and Quality Department) at the provincial level.Footnote 64 However, in practice, these activities are not always implemented.Footnote 65

3.4 Strong Public Policies to Aid in the Identification and Registration of Geographical Indications

Since 2005, several programs have been launched in Vietnam to support the protection of GIs. According to Decree 122/2010/ND-CP,Footnote 66 the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development and the Ministry of Industry and Trade shall assume prime responsibility for, and shall coordinate with People’s Committees of provinces or centrally run cities in, identifying specialties, features of products, and processes of production of specialties bearing GIs that are managed by ministries, branches, or localities.Footnote 67 In this context, the Ministry of Sciences and Technology launched the first phase of the national ‘Program 68’ in 2008 aimed at identifying specialty products that could benefit from intellectual property protection, either as a GI or as a collective/certification TM.Footnote 68 Program 68 runs throughout Vietnam on a quota system of three products per province. The Program includes one product to be protected as a GI, the second product as a collective TM, and the third product as a certification TM.Footnote 69 While the first phase of Program 68 led to the registration of GIs and TMs, the second phase dealt with the management of GIs, i.e., post-registration issues and the issuance of regulations for the management and control of the use of GIs.

A number of programs that run at the provincial and district levels also aim to support the registration of GIs and TMs, such as the program run by the Province of Quang Ninh, which has aided in registering nine GIs/TMs since 2010.Footnote 70 International projects funded by the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) or the French government have supported particular GIs with the aim of reinforcing the value chain and small producers.Footnote 71 For all those programs, the Vietnamese authorities enlisted the expertise of national research institutes such as CASRAD, the Institute of Policy and Strategy for Agriculture and Rural Development (IPSARD), and private consulting agencies to develop the GI application dossier and prepare the management documents and regulations.Footnote 72

Vietnam has also been very active in the GI debate at the international level. The Government of Vietnam represents the interests of GI producers when negotiating bilateral agreements in order to get international protection for their GIs. In particular, Vietnam has negotiated FTAs with Europe and several countries in the Pacific, including the United States, notwithstanding the fact that the European Union and the United States do not share the same vision for GIs.Footnote 73

The Government of Vietnam has also acted to facilitate the registration of national GIs outside Vietnam. For example, the denomination Nuoc Mam Phu Quoc fish sauce was registered as a protected denomination of origin in the European Union in 2012.Footnote 74 In October 2012, Vietnam and the European Union signed the Framework Agreement on Comprehensive Partnership and Cooperation between Vietnam and the European Union in order to promote the mutual recognition of their respective GIs.Footnote 75 In 2015, Vietnam and the European Union also completed the negotiations for an FTA providing, among other provisions, for the mutual recognition of 39 Vietnamese GIs in the European Union and the protection of 171 EU GIs in Vietnam.Footnote 76

In conclusion, the concept of appellation of origin was certainly first introduced into the Civil Code of Vietnam as a result of the collaboration between Vietnam and the French government. Later, Vietnam introduced the concept of GIs as part of Vietnam’s obligations in order to join the WTO. Still, Vietnamese policy-makers at both national and regional levels have gone far beyond the mere enactment of a legal framework establishing the protections of GIs as an international obligation. In particular, Vietnam has actively promoted a series of public policies for increasing the number of GI registrations and educating GI producers and stakeholders to correctly manage GIs. This has led to a positive dynamic and an increase in GI protection of four to five GIs per year in Vietnam over the past several years.

Yet, while this State-driven process has led to the registration of forty-nine GIs so far and has resulted in the promulgation of forty regulations for the management of GIs in Vietnam, there has been little use of GIs in practice so far, as illustrated by the two case studies in the following section. This again indicates the partial dichotomy between the existing legal protection of GIs in Vietnam and the actual (still limited) impact of these GIs on socio-economic development in Vietnam.

4 Case Studies on the Use of Geographical Indications and Their Contribution to Socio-economic Development in Vietnam

Bearing in mind the stated development policy goals attached to GIs,Footnote 77 this section reviews two cases studies. First, it presents the case study of the GI-denominated fried calamari from Hạ Long, a product that is characterized by a strong local market and local consumption in Vietnam. Second, it presents the case study of the GI-denominated star anise from Lạng Sơn, a product that is instead primarily export-oriented. By presenting these two case studies, we seek to show the extent to which the actual use of GI labels on local products in Vietnam may be impacted by the commercial and marketing strategies of local actors and how such strategies may generate different socio-economic development outcomes.

4.1 The Fried Calamari from Hạ Long: Strong Local Market and Short Marketing Channels

The fried calamari from Hạ Long (Hạ Long fried calamari) is a typical product of Hạ Long City, in Quảng Ninh Province (Northeast Vietnam). Hạ Long fried calamari have been produced by traditional family units since 1946Footnote 78 and derive specific taste and characteristics from both the high quality of the calamari found in the Gulf of Tonkin and the technical know-how of the processors/producers. As a typical product listed among the fifty most delicious dishes in Vietnam in 2012 and the one hundred most delicious dishes in Asia in 2013,Footnote 79 Hạ Long fried calamari have long enjoyed a very good reputation among local consumers, and the producers benefit from the millions of tourists that the nearby Hạ Long Bay (a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Site) draws to the region every year.Footnote 80

Proof of the reputation of the fried calamari from Hạ Long is not only the mass consumption of up to 1,500 kg/day in Hạ Long City but also the widespread misuse of the name on squid products that do not come from Hạ Long, as it happened particularly in the Quang Yên Province.Footnote 81 Initially, the first objective of the calamari producers was in fact to stop, or at least counter, the misuse of the product name – Hạ Long – and promote the specific quality and characteristics of genuine products to consumers inside and outside the Hạ Long region. In December 2013, in order to protect the Hạ Long name, the People’s Committee of Hạ Long City (at the District level) registered the GI Hạ Long for fried calamari.Footnote 82 Subsequently the Committee delegated the right to manage the GI to the District’s Economic Department,Footnote 83 following the establishment of the association of producers/traders of fried calamari in the region. In order to use the GIs, producers have to become members of the association. As part of their obligations as members of the association, producers have to abide by the conditions set forth by the association and reflected in the GI specification. This includes, among others, the location of the processing and production facilities in Hạ Long City and a minimum of three years of experience in the production and trade of fried squid.Footnote 84

The whole project – including surveys, mapping activities, determination of the quality of the raw material, establishment of the association, and registration of the GI – benefited from public funding from the Quảng Ninh Province (80 per cent of the total budget amounting to about 90,000 USD) and the Hạ Long City District (20 per cent of the total budget). It is worth mentioning that the project initially involved educational trips to Phu Quoc Island for producers/traders of the Hạ Long fried calamari to learn from the experience of the producers/traders of the Phu Quoc fish sauce; however, this trip was cancelled due to lack of funding.Footnote 85 Interestingly enough, both the Phu Quoc fish sauce and Hạ Long fried calamari GI initiatives exclude the fishermen who provide the raw materials for the processing of the GI products even though the geographical area in which fish must be caught is strictly defined in both cases.Footnote 86 As a result, the association of producers/traders of the Hạ Long fried calamari is rather small and gathers producers/traders only, with a total membership of twenty-three trader families.Footnote 87 Among them, three ‘pilot families’, who have the largest processing facilities, have been testing the use of the GI label since its registration in December 2013. As of September 2015, a total of fifteen families were granted the right to use the Hạ Long GI by the District’s Economic Department upon payment of the prescribed use fees (around 53 USD for a three-year period).Footnote 88

Taking a closer look at the commercial and marketing aspects of the Hạ Long fried calamari, it is noteworthy that all members of the association are involved in short marketing circuits in the two markets in Hạ Long City (‘Hạ Long I market’ and ‘Hạ Long II market’, respectively). These markets are overwhelmingly and traditionally local, with about 95 per cent of the volume of traded fried calamari from Hạ Long being sold locally, either through direct sales to final consumers in the two main markets of Hạ Long City with no middlemen involved (50 per cent of the total trading volume) or to restaurants, hotels, and retailers located in Hạ Long City via short marketing channels involving middlemen (about 45 per cent of the total trading volume).Footnote 89 The remaining 5 per cent of the trading volume of Hạ Long fried squid is sold to final consumers in big cities of other provinces (such as Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi, where two shops sell this product) through a number of middlemen and distributors such as supermarkets, food stores, and retailers in urban areas, which leads to lower profit margins for producers.Footnote 90

While the high concentration of traders in the two markets of Hạ Long City has led to fierce competition among producers – which has discouraged some producers who are not members of the association from conducting business thereFootnote 91 – direct sales and contact with consumers have contributed to building the reputation of the product while providing producers with more flexibility in setting selling prices. This is shown in the higher prices charged by the producers who sell directly on the markets with no middlemen (about 14–15 USD/kg in December 2014; up from less than 9 USD/kg in 2007) compared to the lower prices charged by the producers who are involved in longer marketing channels with middlemen (about 13 USD/kg).Footnote 92 Among those producers who sell directly on the market, it is of particular interest that the use of the GI label by the three pilot families has resulted in an increase in their selling price by about 15 per cent to 17 per cent USD/kg in December 2014, thereby contributing to higher incomes.Footnote 93 In contrast, the price of the fried calamari that incorrectly used the name ‘Hạ Long’ for calamari not produced in Hạ Long is about 9.5 USD/kg.Footnote 94

Besides, the GI initiative seems to have benefited from the communication strategy implemented by the Department of Culture, Sports, and Tourism at the provincial level in 2013.Footnote 95 This strategy intended to raise consumers’ awareness of the Hạ Long fried calamari by organizing tourist visits to the markets, mentioning fried calamari in guide books, participating in fairs and exhibitions, and broadcasting daily on local radio and TV promotion programs about the specific quality and characteristics of the Hạ Long fried calamari.Footnote 96

As a result, according to a number of interviewees, consumers’ demand for Hạ Long fried calamari has greatly increased over the past few years.Footnote 97 Although higher demand by consumers will undoubtedly be welcomed, as an increase in sales volume will lead to higher incomes for local producers/traders, it might also negatively impact the sustainability of primary raw material (i.e., calamari) from the Gulf of Tonkin, where, according to the GI code of practice, at least 70 per cent of calamari should be fished.Footnote 98 Indeed, a number of interviewees reported that the supply of calamari is quickly decreasing due to greater consumer demand and unsustainable fishing practices outside of the reproduction area.Footnote 99 Because of this, producers have been increasingly sourcing their calamari from Central Vietnam, China, Indonesia, and Malaysia, which may affect the quality of the fried calamari.Footnote 100 Yet if the 70 per cent minimum rule is not met, the fried calamari might be considered a fraud as it will not meet the requirements of the code of practice.

4.2 The Star Anise from Lạng Sơn: Export-Oriented Product with Long Market Access Chains

Star anise is a dark-grey spice that has six to eight equal, separate petals arranged in a star shape. The Province of Lạng Sơn in Northern Vietnam, located on the border of the Guangxi Province in China, is a very important production site of star anise, occupying a total of 35,575 hectares out of a total production area of 58,500 hectares within the whole country, about 60 per cent of the total cultivated area.Footnote 101 The total production output is estimated to be between 6,000 and 10,000 tons/year.Footnote 102 Additionally, there are two value chains: the production of dry star anise and star anise oil. The process of planting and harvesting star anise is based mainly on traditional know-how and experience, including manual techniques.

In February 2007, the appellation of origin was granted to the People’s Committee of Lạng Sơn Province with funding from the government program ‘Program 68’.Footnote 103 The Province later delegated the right to manage the appellation of origin to its Department of Science and Technology. Subsequently, in 2008, the association for the production and marketing of star anise from Lạng Sơn was established. In contrast to the association for the production of Hạ Long fried calamari, membership to the Lang Son star anise association is not a requirement for the right to use the GI.Footnote 104 Still, compared to the relatively small association for the Hạ Long fried calamari, the association for the Lạng Sơn star anise is open to farmers, processors, collectors, and traders and has a large membership; about 700 out of a few thousand households are engaged in the production and trade of star anise in the Lạng Sơn Province. However, its actual activities were reported to be very limited and most members are not even aware of the very existence of the GI.Footnote 105 Surprisingly, compared to the high number of households involved in the production and trading of the star anise, only two export companies have been granted the right to use the GI so far, Aforex Co., Ltd. and Vinaspaex Co., Ltd.Footnote 106 Moreover, only one of them has been using the GI label. Also, there has been no observable difference in the selling prices of star anise grown in GI-protected areas and non-protected areas (between 1.3 and 2.7 USD/kg in May 2014, depending on the quality of the star anise). Neither has there been proof of economic benefit from the use of the GI label.Footnote 107

The very limited use of the GI label in practice may be explained by a number of factors, including low awareness and lack of interest by local stakeholders in the GI value, as well as the absence of involvement by local authorities in the promotion of the GI and GI products.Footnote 108 All these factors seem to be connected to the lack of collective action, cohesion, and collaboration amongst the high number of farmers, processors, collectors, and traders involved in the production and trading of the Lạng Sơn star anise. But most impactful are the GIs’ marketing channels, as will be explained below.

In actual figures, only 15 per cent of the total production of Lạng Sơn star anise is sold on the domestic market. Instead, about 80 per cent of the products are estimated to be exported to China (as star anise oil) and India (as dry star anise). Both countries use star anise for culinary and medicinal purposes.Footnote 109 The remaining 5 per cent of the products are exported to other countries such as Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand. Star anise is also exported to European countries such as France, Germany, and Belgium, where the spice is used to improve the flavour of wine and other beverage products.Footnote 110 Therefore, the marketing channels for star anise are characterized by a very large number of middlemen and long chains of intermediaries at the regional and international levels.

There are a number of reasons for China and India’s prominent roles in the trade of the Lạng Sơn star anise. On the one hand, China and Vietnam are the two largest producers of star anise in the world. However, unlike Vietnam, where the domestic demand is very low and the majority of its production output is exported, China is the largest consumer of star anise in the world and exports only 5 per cent of what it produces.Footnote 111 Because its domestic production does not meet its domestic demand, China relies extensively on imports of star anise from Vietnam, which are estimated to be thousands of tons per year.Footnote 112 According to a number of interviewees, a large part of this trade takes place through unofficial exchanges at the border between farmers, where the transaction is completed without written contracts or certificates of quality.Footnote 113

On the other hand, star anise is widely used in Indian cuisine. It is a major component of garam masala: an aromatic mixture of ground spices used as a base in many Indian dishes. However, because the production of star anise in India is limited to a part of the Arunachal Pradesh State in the northeast, India has become the largest importer of star anise, accounting for 50 per cent of world imports from production countries, such as Vietnam and China.Footnote 114 Because the free trade agreement between India and Vietnam, which came into force on 1 January 2014, requires the removal of all import-export taxes (following the signing of the ASEAN-India Trade in Goods in 2009), Indian importers have become more interested in importing star anise from Vietnam rather than China, which still imposes a 30 per cent export tax duty.Footnote 115

Given this situation, the value and utility of the GI label is practically non-existent. According to the interviewees, importers who buy star anise from the two export companies with the right to use the GI seem to deliberately opt out of using the label for a number of interesting reasons: Chinese traders want their customers to think that the star anise was grown in China, so they re-package star anise from Lạng Sơn with a Chinese logo, and Indian traders want to hide the origin of star anise from their own competitors to keep their supply sources a secret.Footnote 116 The export companies with the right to use the GI label also explained that when they tried to negotiate the use of the GI label, their customers threatened to find other suppliers.Footnote 117 Thus, the use of the GI label is useful only within the domestic market.Footnote 118

However, between these two export companies, one exports its entire production to foreign markets and thus does not use the GI at all, while the other company exports about 90 per cent and sells the rest in its local shop, resulting in a very limited use of the GI label.Footnote 119 Ironically, when visiting this one shop, the GI logo had been affixed to not only the star anise’s packaging but also the cinnamon’s packaging. The sales manager of this company explained that the use of the GI logo on the cinnamon packaging was meant to identify the commercial origin of its products – regardless of whether the product was in fact cinnamon or star anise – and promote the image of the company as if the GI were owned solely by this company.Footnote 120

5 Discussion

So far, our study has examined the use of the GI registration scheme and two particular GI labels in the context of an emerging country, Vietnam, which actively promotes GIs as a socio-economic development tool. The analysis in this section hopes to provide valuable insights into an important issue, namely identifying the legal and other contextual factors that may hinder the positive impact of a GI system in an emerging country. In particular, from the case studies above, our research suggests several impediments at three separate but interdependent levels: (a) the legal and institutional framework, (b) the commercial and marketing channels, and (c) the collective action of producers within the GI initiatives.

5.1 Legal and Institutional Framework

First, with respect to the legal and institutional framework, our analysis shows that the definition of GIs and its application in practice in Vietnam are more in line with the definition of the appellation of origin in the Lisbon Agreement than with the definition of GIs in TRIPS, as Vietnam law requires a very strong link to the origin of products. In other words, this criterion is a considerably demanding criterion for registering GIs in Vietnam.

Perhaps because of this stringent criterion, the overwhelming majority of registered names of local products are protected through a collective or certification TM comprised of the relevant geographical name. There were about 116 collective and 72 certification TMs registered as of May 2013, compared with only 43 GIs.Footnote 121 These trademarks were registered following the same top-down process with State agencies, which own the certification trademarks or, at the initiative of the creation of the associations, the collective trademarks.Footnote 122 Furthermore, while there is no need to demonstrate a link with the place of origin for TMs, and although in other jurisdictions such as the European Union, the scope of protection is weaker for TMs than for GIs, the law in Vietnam allows for the registration of geographical names as collective TMs and certification TMs.

Second, the quota system under Program 68 to support GIs and TMs has resulted in some geographical designations being registered as TMs and not GIs, even if the link with the origin is very strong. For example, Shan tuyết tea from Moc ChauFootnote 123 has been registered as a GI, but the Shan tuyết tea from Suối Giàng in the Province of Yen Bai,Footnote 124 though described with as many details as the GI Moc Chau Tea, is protected as a certification TM because there was already one GI in the same province as the cinnamon of Van Yen.Footnote 125

Third, and most importantly, the State-driven process has been successful in registering forty-nine GIs and in having them protected in the European Union. The government also remains in charge of enforcing GIs. In 2013, the Vietnamese government also successfully managed to obtain the cancellation of a Chinese trademarkFootnote 126 comprising the designation Buon Ma Thuot Coffee, a GI registered in Vietnam since 2005.Footnote 127

Yet this top-down approach may also negatively impact and ultimately jeopardize the initiative and involvement of the producers in seeking GI registration and later in managing the GI. This top-down approach also will inevitably impact various operators in the supply chain who use the GI (technically, the right to use the GI, as the State remains the holder of most rights related to the GI). This can also impact the management of GIs and GI-denominated products. Certainly, the rights that belong to the State can be delegated to the collectives of producers, as provided by the Vietnam IP Law.Footnote 128 But subsequent decrees have given more power to the State. For example, Article 4 of the Decree 122/2010/ND-CPFootnote 129 provides that ‘People’s Committees of provinces or centrally run cities shall file applications for registration and organize the management of GIs used for local specialties and license the registration of collective marks or certification marks for geographical names and other signs indicating the geographical origin of local specialties.’

Finally, even though the Vietnamese legal framework for GI protection certainly is on par with all other WTO countries, legal protection is not sufficient in itself to turn GIs into successful tools for socio-economic development. Legal protection is a necessary condition for the success of a GI system. However, so are a number of market- and product-specific conditions, as will be shown below. In other words, the success or failure of a GI-system to unleash the potential for GI protection for the purpose of socio-economic development remains heavily dependent on context-specific conditions.

5.2 Relevance of Commercial and Marketing Channels

A number of context-specific issues have emerged as particularly relevant in explaining both the ‘success’ and ‘failure’ of GI initiatives. At the operations level, by contrasting the cases of the Hạ Long fried calamari and Lạng Sơn star anise, we see the importance of taking the commercial and marketing channels into account when analysing the extent to which GI labels are actually used in an emerging country.

First, our empirical findings suggest that, especially in the case of the Hạ Long fried calamari, a strong local market with traditional short marketing circuits is important factors for building the reputation of a local product and empowering local producers who are able to set prices more easily. This is shown by the higher selling prices that the use of the GI label has allowed. In contrast, the domestic market for the Lạng Sơn star anise is virtually non-existent and the use of the label is very limited, thus not affecting selling price or sale volume. However, we do not suggest that the findings of this case study extend to other export GI products from emerging countries. For instance, both DarjeelingFootnote 130 tea and Café de ColombiaFootnote 131 are successful emblematic GI products with a strong export focus, which should thus lead us to make more nuanced considerations. In reality, the penetration into the market for a labelled GI product also depends strongly on the producers’ collective organization and its knowledge and skills about GIs, as will be shown in Section 3.5 below.

Second, we have found that the marketing channel that is adopted may be linked to the nature of the product. The Hạ Long fried calamari is a processed food product sold locally, whereas the star anise from Lạng Sơn is a raw product, usually processed into oil before being sold in export markets without the GI label. The case study of the Lạng Sơn star anise demonstrates the need to ‘decommodify’ this product, and other spices, at the global level in order to better value the spices’ origin, as has been done for coffee, tea, pepper, or more recently, salt.Footnote 132 A ‘de-commodification’ process would allow the GI value to increase in the international market, as the GI would gain recognition with customers, which would allow for price premiumsFootnote 133 as well as higher earnings due to the non-applicability of tariffs for commodity products.Footnote 134

5.3 Importance of Collective Actions by Producers

Finally, we argue that the commercial and marketing channels of these two products have largely affected the opportunities for producers to take ownership of the GI initiatives. Whereas the producers of fried calamari sell their products to customers in traditional local markets at a price set by them, the producers of the Lạng Sơn star anise cannot control where the product is eventually sold nor its final packaging, considering that 85 per cent of the production is sold to traders who re-sell the product in their own country or to other countries. Moreover, the fact that the two export companies with the right to use the GIs have not managed to impose the use of the GI label clearly illustrates the one-sidedness of the negotiations and the Vietnamese producers’ lack of negotiation skills. To go deeper into the issue, even though the right to use the GI was granted by a State agency, it is, in reality, simply denied by importers at the transaction level. This leads to a situation in which importers expropriate the legal right from Vietnamese producers and traders to use the GI, which impedes the potential of the GI initiative to bring about economic benefits. Therefore, we argue that an intervention by the State to restore the right to use the GI would be welcomed.

By supporting the right to use the GI labels, producers would become more aware of the utility of the GI label and actually understand its implications. For example, while producers of fried calamari actively promote the GI label to get a higher selling price, most producers of the star anise are not aware of the very existence of the GI logo. Furthermore, the only company utilizing it in the domestic market affixes the GI logo on other products, such as cinnamon, in order to promote the image of the company. This clearly demonstrates a lack of understanding of the very meaning of a GI, not to mention the inefficiency or lack of quality control and product inspection due to a shortage of funding and equipment. Once again, some level of State intervention would be useful to increase awareness of the meaning of a GI and its value as well as to strengthen quality control of the GI product.

6 Conclusion

In conclusion, in light of the above, the highest priority in Vietnam should be to empower local farmers and producers to use the GI system and the GI labels beyond the current status quo. Undoubtedly, this is a challenge in the context of a State-driven economy in which GI policies are developed through top-down governance. Still, the law in Vietnam permits that the right to register and manage GIs can be delegated to collectives of producers. Such a management model could be applied more often in order for producers and producer associations to play a more prominent role in the GI landscape than they do today. Naturally, Vietnam continues to go through a learning process regarding the use of the GIs, after a first successful step of registration of GIs, as many other countries of the region. Still, GI protection can have a beneficial impact on economic development in many areas of the economy in Vietnam, and thus producers should learn to use the GI system to a fuller extent to capture more of its promises.