8 - A Window for the Pain: Surface, Interiority and Christ’s Flagellated Skin in Late Medieval Sculpture

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 May 2021

Summary

ONE of the most striking developments in late medieval visual culture concerns the emergence of a new type of sculpted image of Christ Crucified towards the beginning of the fourteenth century. Known to modern scholarship as the crucifixus dolorosus, these objects display an obsessive and extreme attention to the wounding of Christ's body, almost to the point where the sheer number and variety of wounds threaten to overwhelm the surface and obliterate the skin, in other words, almost to the point at which the body is flayed. Such images appear to have enjoyed something approaching universal popularity throughout Europe, even though they sometimes met with official disapproval. In modern scholarship they have generally been marginalized because of the lack of secure information about their authorship and dating, although recent technical analysis has made significant contributions to our knowledge. Their reception has also been dogged by a tendency to interpret their remarkable features as a simple piling-up of gore. Again, recent analysis suggests a much greater level of sophistication, not only in their facture but also in their consumption by late medieval beholders. The multilayered and highly articulate surfaces of these works encourage the viewer to read through that surface, stripping off Christ's skin and flesh as though visually flaying his body in the process of devotional adoration. Indeed, flaying – mediated through the metaphors of the body as book and the flesh as fabric – offers a powerful framework through which to interpret the significance of these sculptures. Before applying that framework, however, we must begin by stepping back from the sculptures in order to address the meaning of wounding itself at the beginning of the fourteenth century.

We are in the pit of Hell, following as Dante the pilgrim descends through the infernal kingdom with his guide, the classical poet Virgil. He is making his way across the seventh circle, where the sin of violence is punished. The two men have just forded a river of blood, thick with boiling sinners, and they stand on the fringe of a trackless wood. The pilgrim is puzzled. The place echoes to cries of distress, but the source of these laments is nowhere to be seen. Virgil encourages him to reach out and pluck a branch from a thorn bush. In a poem full of shocking scenes, what follows is among the most disturbing and uncanny.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

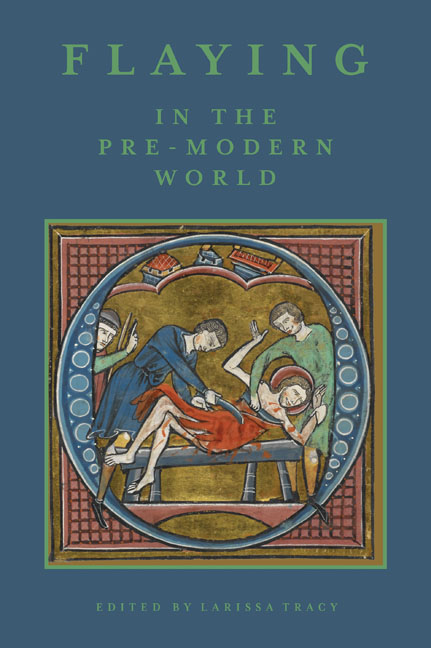

- Flaying in the Pre-Modern WorldPractice and Representation, pp. 208 - 239Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2017