5 - Skin on Skin: Wearing Flayed Remains

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 May 2021

Summary

[T]he skin is the sign of our transformability, our […] ability to become other.

IN the Florentine Codex (c. 1588), Spanish chronicler Bernardino de Sahagún describes the Aztec festival of Tlacaxipehualiztli. In this celebration honouring the skin-garbed god Xipe Totec, elite captives of war were flayed and their removed skins worn for twenty days by priests, a practice called neteotquiliztli, ‘impersonating a god’. Jill Furst observes, ‘The prisoner became Xipe and died, but his skin retained the god's life force’, and the two were taken on together by the second wearers. Though dramatic, neteotquiliztli is only one example among many in which skinwearing is assumed to facilitate passage to an alternative state of being. Practices and representations of wearing skin – recognizably animal as well as human – cover a wide generic, geographic and temporal range but follow a similar logic. In the Middle High German verse narrative Salman und Morolf, historical accounts of punitive and prophylactic skin-wearing in Germany and Italy, early modern Icelandic folk traditions and the sixteenth-century English Merry Ieste of a Shrewde and Curst Wyfe Lapped in Morrelles Skin for Her Good Behauyour, the removed and re-donned skin, detached from that which originally gave it meaning, initiates a mode of border-crossing, becoming a floating threshold between one form of the self and another.

Much of the burgeoning scholarship on the skin recognizes its literal and metaphorical function as limen, a space that Victor Turner describes as ‘represent[ing] the midpoint of transition’. The skin, says Steven Connor in his wide-ranging Book of Skin, is a ‘milieu’ that he explains as a ‘midplace […] where inside and outside meet and meld’. In her discussion of practices of bodily inscription that take place on and through the skin, such as branding and tattooing, the anthropologist Enid Schildkrout also emphasizes the ‘liminal quality of skin’, arguing that the integument constitutes an ‘ambiguous terrain at the boundary between self and society’. The skin as limen may be read as threshold or barrier: as the former, it allows controlled entry; as the latter, it separates and individuates, distinguishing self from what is outside itself.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

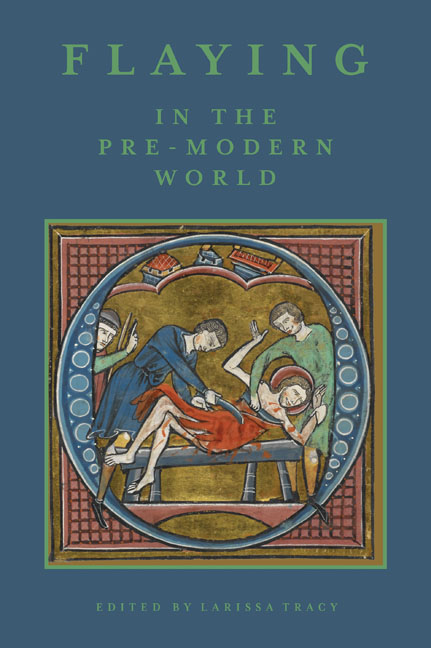

- Flaying in the Pre-Modern WorldPractice and Representation, pp. 116 - 138Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2017