Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction: being female

- Part I Women in perspective

- Part II Women and society

- Part III Women and their environment

- Part IV Women and specific disorders

- Part V Women and treatment

- 33 What women want from medication

- 34 What women want from services: a patient's perspective

- 35 Complementary and alternative therapies

- Contributors

- Index

34 - What women want from services: a patient's perspective

from Part V - Women and treatment

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 02 January 2018

- Frontmatter

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction: being female

- Part I Women in perspective

- Part II Women and society

- Part III Women and their environment

- Part IV Women and specific disorders

- Part V Women and treatment

- 33 What women want from medication

- 34 What women want from services: a patient's perspective

- 35 Complementary and alternative therapies

- Contributors

- Index

Summary

In many respects, the requirements and needs of women within mental health services are not very different from those of their male counterparts. However, the way in which they are perceived and treated can be quite distinct.

My own introduction to psychiatry in the 1970s, at the age of 18, was particularly bizarre. After I took a massive aspirin overdose, a male psychiatrist interviewed me on a ward in a general hospital. I spoke to him about the way I felt about myself and my life. He later approached my parents and asked if I had been dropped on the head as a baby. It was a singularly ignorant and dismissive response that I have, unfortunately, encountered time and again.

In spite of the increase in the number of female psychiatrists and advances in mental healthcare and treatments, the predominant view with regard to female patients often remains paternalistic and outdated. Women's mental illness still tends to be seen, in Victorian terms, as ‘hysterical’, and self-harm and suicide attempts are frequently criticised as ‘attention-seeking’ or ‘manipulative’.

The archaic assumption that women are the main caregivers for those in their lives can encourage them to ignore their own complex needs. Moreover, services can blame them for their inability to continue in their roles as partners, daughters and mothers. The results for women can be manifold – the children of single parents can be unilaterally removed and adopted, their sense of themselves as failures can be exacerbated, and the coercion they can feel to return to these roles often overrules the need for time to become well.

The expectations placed on women vary according to socioeconomic factors, faith, sexual orientation, disability and ethnicity. However, I believe that there are commonalities that bind women together.

From the onset of menstruation to the cessation of the menopause, women can be at the mercy of their changing hormones. The effects of these can be physical and psychological: mood swings, stomach cramps, heavy blood loss, headaches and irritability can be debilitating before and during menstruation. In addition, the fear of, or desire for, pregnancy can increase the pressures placed on women. The menopause's night sweats, hot flushes, headaches and sleep disturbances can leave women tired, anxious and possibly mourning an aspect of their lives that defined them as female.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

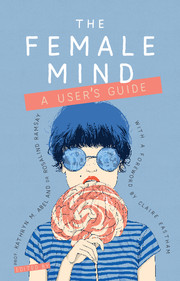

- The Female MindUser's Guide, pp. 227 - 230Publisher: Royal College of PsychiatristsPrint publication year: 2017