The Construction of Vernacular History in the Anglo-Norman Prose Brut Chronicle

The Construction of Vernacular History in the Anglo-Norman Prose Brut Chronicle from Part II - Reconstruction and Response

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 February 2018

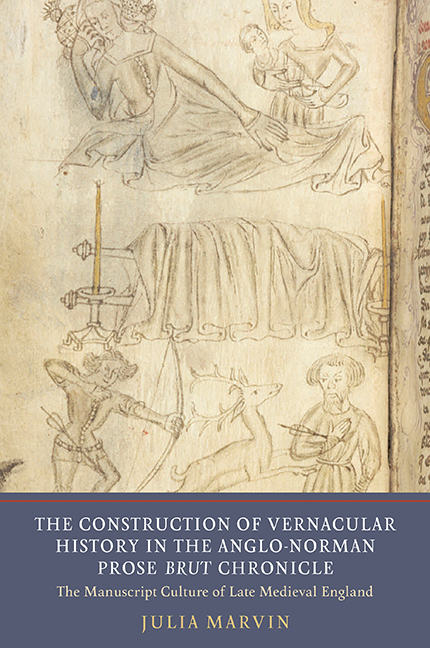

Illustration is another kind of supplementation that is difficult to appreciate outside the physical context of the manuscript. Like apparatus and annotation, it resists simple definition. Illustrations may provide decoration, ways of demonstrating the status of the work – iconographically and/or economically – and pointers towards interpretation. They may do as much to test or question the text they accompany as they do to repeat its content in another form, as a variety of apparatus that helps guide readers through the work in question and assigns extra significance to particular moments by singling them out for attention. They are limited to manuscripts with some space to spare and, for the most part, commissioners with money to spare. In addition to serving the function of apparatus, they of course constitute works in their own right: such study as Anglo-Norman prose Brut illustrations have received has generally been in isolation from the textual context. They are found rarely throughout the prose Brut tradition, and among Anglo- Norman prose Brut manuscripts only in a very few insular manuscripts and the three late luxury manuscripts produced on the Continent. Although, as Martha Driver and Michael Orr note, there appears to have been a drive towards standardization of illustrative matter in the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the surviving illuminations in Anglo-Norman prose Brut manuscripts do not suggest much in the way of a iconographic tradition.

Insular Illustrations

The manuscripts with illustrations are among the most highly decorated of the insular Anglo-Norman prose Bruts, although not themselves particularly fine or lavish productions. Unsurprisingly, their illustrations appear at the beginning of the chronicle and are the manuscripts’ most extravagant feature. In the two manuscripts with the Latin poem encapsulating the post- Conquest kings’ reigns, one (RD329) has a completed, colorful set of king portraits and genealogies and the other (P511/19) space for such portraits; after this emphatic triple gesture directing the reader – via words, images, and diagrams – to think of British history as a series of genealogically linked portraits, an approach much akin to that of the Oldest Version's narrative, the Albine prologue and Brut chronicle are marked only with nicely made large initials.

To save this book to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle.

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox.

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive.