5 - Chinese magic and magic in China

from Part II

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 July 2016

Summary

Chinese magic

As we saw in the last chapter, India was unchallenged as the apparent focus and origin of magic and mystery, especially in Britain and the United States, but also on the European continent. Nonetheless, China and then Japan gradually became more prevalent in the magical imagination of the West, especially after the second half of the nineteenth century. Indeed, until that time, European magicians would have seen very little technical difference between the performance of Indian and Chinese magic on the stage, and audiences would have differentiated mainly (and perhaps exclusively) by aesthetic issues: a ‘Chinese’ performer would be clothed in flowing silken robes, while an ‘Indian’ would be more scantily clad and less ostentatious; a ‘Chinese’ magician was dramatically theatrical, while an ‘Indian’ appeared more esoteric and occult. There was a different kind of Oriental glamour involved. However, these apparently cosmetic differences did have some implications for the kinds of feats that were possible for magicians: for instance, the flowing robes of a ‘Chinese’ magician enabled the production (and disappearance) of larger objects from the person of the magician himself, such as the famous goldfish bowl. The aesthetics facilitated technical feats.

Sidney Clarke suggests that audiences might have associated Indian conjurors with greater expertise with the Cups and Balls and Chinese with the Linking Rings, but suggests that this was a matter of degree rather than absolute identification. The origins of such tricks were hazily ‘Oriental’ in the public imagination. It was not until later, in the early years of the twentieth century, that audiences would become accustomed to seeing the Basket Trick and the Mango Trick on the stages of Europe and North America; while modern audiences would associate these with ‘Indian Magic’, the same basic feats were also performed in China (where the basket might be a lacquered box and the mango might be a melon), such minor technical changes produced concomitant changes in effects. As we saw in the last chapter, there remains some historical confusion about whether certain ‘Indian’ tricks really originated in China – such as the fabled Rope Trick – but the opposite is also true, with some modern commentators attributing the origins of the ‘Chinese Rings’ to Indian street magic.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

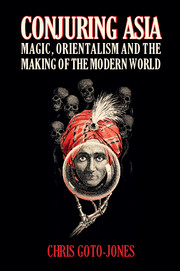

- Conjuring AsiaMagic, Orientalism and the Making of the Modern World, pp. 205 - 264Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2016