Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 25 May 2019

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

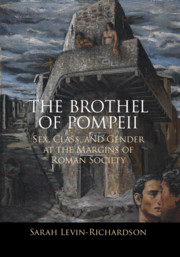

- The Brothel of PompeiiSex, Class, and Gender at the Margins of Roman Society, pp. 217 - 232Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2019