Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations

- Editorial Note

- Preface

- 1 Setting the Scene: American Ballet and Jerome Robbins

- 2 Toward a First Ballet: Fancy Free Takes Shape

- 3 Creating Fancy Free: A Long-Distance Collaboration

- 4 The Music of Fancy Free: The Sketches and Score Explored

- 5 The Fancy Free Premiere and a Move to Broadway

- 6 Toward a Second Ballet: Bye Bye Jackie and the Creation of Facsimile

- 7 The Music of Facsimile: The Sketches and Score Explored

- 8 The Facsimile Premiere and Legacy of the Ballets

- Epilogue: Bernstein and Dance

- Bibliography

- Index

2 - Toward a First Ballet: Fancy Free Takes Shape

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 March 2021

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations

- Editorial Note

- Preface

- 1 Setting the Scene: American Ballet and Jerome Robbins

- 2 Toward a First Ballet: Fancy Free Takes Shape

- 3 Creating Fancy Free: A Long-Distance Collaboration

- 4 The Music of Fancy Free: The Sketches and Score Explored

- 5 The Fancy Free Premiere and a Move to Broadway

- 6 Toward a Second Ballet: Bye Bye Jackie and the Creation of Facsimile

- 7 The Music of Facsimile: The Sketches and Score Explored

- 8 The Facsimile Premiere and Legacy of the Ballets

- Epilogue: Bernstein and Dance

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

Finding a Subject

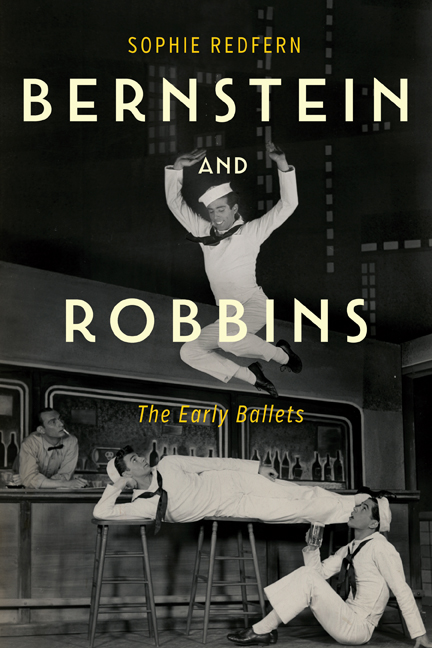

Robbins's quest to produce his first ballet in the early 1940s had the unfolding events of World War II as its backdrop: Pearl Harbor was attacked on December 7, 1941, and the United States declared war the following day. In later life Robbins reflected on the war years and the horrors occurring in Europe: “From 1939 to 1944, I was trying to be a dancer, and all that was somewhere else.” He was spared active wartime service by an underlying asthmatic condition that prevented his being conscripted, so his view of the war was through what he encountered of daily life in New York City and elsewhere when touring. He saw the effects of the war—the influx of sailors enjoying New York before sailing to far-off conflicts, and soldiers being transported across America on packed trains—but ultimately, he observed it from a distance.

The young dancer's choreographic aspirations and his desire to move away from the Russian ballet heritage led him to devise numerous scenarios for submission to the company's co-director and prima ballerina, Lucia Chase. He sought inspiration from a wide range of sources including comic strips, the tale of Cain and Abel, short stories by Horatio Alger, and the works of Mark Twain. These were all, as he would later admit, “rather elaborate.” Charles Payne, executive managing director at Ballet Theatre, wrote regularly to Robbins offering advice to the driven but naive choreographer. In January 1943 Payne astutely remarked, “no matter how intrinsically worth while [sic] your first ballet is, unless it appeals to the public generally, you will never get a chance to do another.” The hope was that Robbins would, for his first endeavor at least, abandon the lengthy and rather serious scenarios he was planning and create a work that would be popular with a wide audience. If his first ballet were a success he would certainly get the opportunity to choreograph another; if his first ballet were a failure, the chance of anyone financing him in the future would be slim.

Eventually, Robbins took heed of the wealth of advice he was being given by those in the business: “I think it was Anatole Chujoy, the editor of Dance News, who said to me, ‘Why don't you get together a small ballet with a few people?’”

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Bernstein and RobbinsThe Early Ballets, pp. 32 - 64Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2021