Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Introduction

- Part I Reconstructing the History of Atlantic Modernity

- 1 The American Divergence, the Modern Western World and the Paradigmatisation of History

- 2 The Limits of Recognition: History, Otherness and Autonomy

- 3 On Being in Time: Modern African Elites and the Historical Challenge to Claims for Alternative and Multiple Modernities

- 4 The Sublime Dignity of the Dictator: Republicanism and the Return of Dictatorship in Political Modernity

- 5 The Luso-Brazilian Enlightenment: Between Reform and Revolution

- Part II Comparing Trajectories of Modernity in the South

- Part III Claims for Justice in the History of Modernity and in its Present

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index

2 - The Limits of Recognition: History, Otherness and Autonomy

from Part I - Reconstructing the History of Atlantic Modernity

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 August 2016

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Introduction

- Part I Reconstructing the History of Atlantic Modernity

- 1 The American Divergence, the Modern Western World and the Paradigmatisation of History

- 2 The Limits of Recognition: History, Otherness and Autonomy

- 3 On Being in Time: Modern African Elites and the Historical Challenge to Claims for Alternative and Multiple Modernities

- 4 The Sublime Dignity of the Dictator: Republicanism and the Return of Dictatorship in Political Modernity

- 5 The Luso-Brazilian Enlightenment: Between Reform and Revolution

- Part II Comparing Trajectories of Modernity in the South

- Part III Claims for Justice in the History of Modernity and in its Present

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index

Summary

An Ambiguous Picture

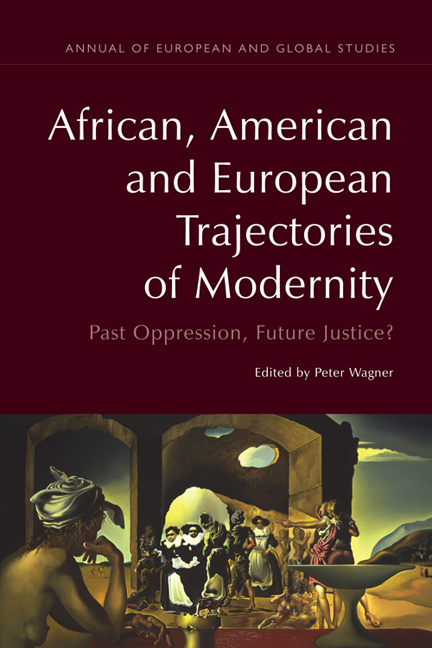

IN 1940, in the United States, Salvador Dalí painted Slave Market with the Disappearing Bust of Voltaire. It was the first work in a series of paintings whose focus was the Americas. This painting is an example of double imagery representing, from one perspective, Jean-Antoine Houdon's bust of the iconic Voltaire and, from the other, two traders (presumably Dutch), with the immobility of a Velázquez painting, outlined against a hole which seems to form some kind of entrance. The entire scene is contemplated from the left by a young, half-naked white slave (Gala) whose posture is similar to Rodin's Thinker, looking at Voltaire/the two traders. What is common to the traders and Voltaire's bust is that both are surrounded by figures of different slaves (some dressed and present– some nude and fading), ruins and a coastal landscape.

Notwithstanding Dalí's own interpretation of the picture– that ‘by her patient love Gala protected [him] from the ironic world crawling with slaves’, and from the scepticism of eighteenth-century philosophy (Dalí, 1948)– his puzzling picture provides us with a means by which to introduce the main themes of this chapter, subject to the expediency of our interpretation. Both the dialectic gaze of Gala towards Voltaire (and thus the traders) and Voltaire's gaze back (whose eyes are shaped by the heads of the two traders) can be read as a playful representation of the double imaginary of modernity and, more concretely, as an interpretation of the double imaginary of the modern Western philosophy of history. The painting can be seen as an archaeology of a modernity that was fading in 1940. This bi-stable, ambiguous image allows us to reveal the double register of a discourse that can be interpreted as a dispositive of domination and/or justification of the hegemon but also, and at the same time, as the place for autonomy and/or resistance to the domination.

The main objective of this chapter is to analyse the link between the modern constitutive ambiguity of the European philosophy of history and the experience and conceptualisation of the other in order to open a critical debate on the current theorising of otherness provided by theories of recognition.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- African, American and European Trajectories of ModernityPast Oppression, Future Justice?, pp. 42 - 63Publisher: Edinburgh University PressPrint publication year: 2015