1 Introduction: Learning from Unfair Fights

In the aftermath of the Napoleonic wars, French philosopher Victor Cousin concluded that leading military powers need not learn from primitive peoples. “A people is progressive only on the condition of war,” Cousin announced. Those who had “sunk beneath the present time” could expect to be “blotted out from the book of life.” According to this theory, the future was certain to belong to those most advanced in technology and efficient in bureaucracy. In short, there could be no need to study conflicts against so-called “barbarians.”Footnote 1

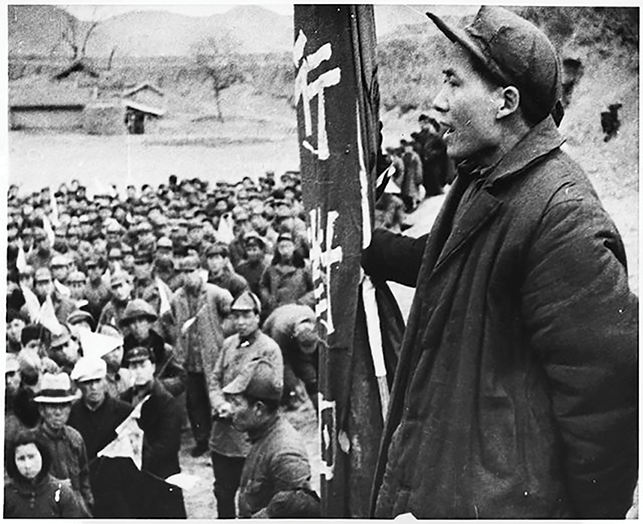

Across the Atlantic, American engineering professor Dennis Hart Mahan disagreed. In a lecture on “Indian Warfare” at West Point, he noted the “struggle of Spain against the genius of Napoleon” as one of many historical examples of “superior” militaries forced to adapt to less powerful opponents. The professor composed his work in response to the Seminoles’ recent destruction of a column of U.S. regular soldiers in Florida, as seen in Figure 1. The solution to fighting asymmetric enemies was not “in imitating the institutions of other nations,” but by adapting one’s own “national character” to best suit the current threat. Mahan believed the U.S. army should not attempt to mimic Native American ways of war, but to apply “science and forethought,” to learn from them and then outpace them.Footnote 2 For most of the two centuries since these men wrote, military thinkers have made an implicit agreement with Cousin; they ignored wars of the weak in favor of wars between great powers. But in the last generation, scholars have returned to the study of asymmetric conflicts: rebellions, insurgencies, and civil wars stretching back to the ancient period.

Figure 1 Engraving, “Viewing the Demise of Major Dade and his Command in Florida,” c. 1870, Wikimedia Commons

Ancient imperial forces understood the concept of asymmetry in warfare. Indeed, one of the earliest texts on war, the 5th-century-BC Histories of Herodotus, established a clear boundary between “Greeks” and “barbarians.” For millennia, wars have produced unequal opponents and dehumanization of enemies. But asymmetric warfare took on its defining characteristics only in the modern era, with the confrontations between European invaders and the resistance they provoked in Africa, Asia, and the Americas. In this new imperial context, conflicts grew more asymmetric as they presented profound gaps between combatants in terms of technology, intelligence production, and law. Though ancient societies may have differed in these categories, the advantages that accrued to modern states brought about new, fundamental disparities. Scholars have tended to split these conflicts based on pejorative characteristics of the weaker side: guerrillas (“small” warriors unable to field heavy weapons), insurgents (rebels from within a recognized polity), irregulars (whose practices fall outside normative military practices), or terrorists (defined by inhumane tactics).

The concept of asymmetric warfare is preferable for two reasons. First, lumping conflicts together under the umbrella term of asymmetry reveals the continuity and centrality of wars between mismatched opponents to an American military tradition that predates the United States. Second, the details of these conflicts, laid out in chronological order, show that strong military forces have struggled more in recent decades, as so-called weak powers have found ways to neutralize defining modern asymmetries of technology, intelligence, and law.

Throughout the modern era, mismatches between strong and weak forces have not been deterministic for military outcomes; asymmetries have cut both ways. The “strong” military, though it enjoys the advantage of funds, and thus technology and firepower, often suffers from deficiencies of morale, and thus intelligence and manpower gathering capabilities. State militaries devote only a fraction of their resources to any given limited conflict, which for the weaker side becomes a total war, as the existential nature of defeat provokes ever more willingness to suffer casualties and escalate the means of violence employed. An initial asymmetry of resources cascades into asymmetries of political aims and political will.Footnote 3 The task of the counterinsurgents becomes more daunting, if expected, to quell all forms of rebellion in occupied territory, whereas the insurgency gains power the longer it survives. Or, as a frustrated Henry Kissinger quipped during the American War in Vietnam, “The conventional army loses if it does not win; the guerrilla wins if he does not lose.”Footnote 4 The nature of these political imbalances has tended to limit the staying power of state military forces deployed abroad, especially if the government in question is a multiparty democracy vulnerable to opposition based on war weariness.

The study of warfare has gained special interest during periods in which it was practiced. Thus, analysis of asymmetric warfare proliferated in the post–Second World War era. Though the global conflict itself comprised mostly conventional combat, the end of the war unleashed the notable asymmetric means of nuclear weapons and national liberation movements. The successful Allied powers, fazed by popular politico-military movements in China, Southeast Asia, and North Africa, demanded some new theory of war to explain current events. Still, most academic attention concentrated on the novelty of nuclear warfare, and perhaps the nuclear focus was merited. Political scientists have posited that democracies tend not to go to war against other democracies. In economic terms, the Golden Arches theory sought to explain how the ties of global capitalism might prevent countries with McDonald’s franchises from fighting one another.Footnote 5 But a better historical rule is that no two countries with nuclear arms have fought direct conflicts, if one sets aside minor border skirmishes on the Sino-Soviet and Indo-Pakistani frontiers.

Another crop of academic work on asymmetric warfare arrived in the 1990s, as American military thinkers sought to find a raison d’être after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of bipolar geopolitics. Newfound interest in wars of the weak surged alongside the U.S.-led Global War on Terrorism, which witnessed rapid conventional campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq, both followed by long counterinsurgencies. The end of that latest conflict presents a good opportunity for a compilation of the existing scholarship, to continue the work of Dennis Hart Mahan in defiance of Victor Cousin types.

Though historians have understudied asymmetric wars compared to conventional operations, a series of historical agents have, like Professor Mahan, sought out previous accounts of mismatched opponents to understand their own times. These connections allow for a cyclical narrative, continuous across the modern era, that consists of speculation about the future of warfare, experience of asymmetric conflicts, and reflection on how best to reform the military based on recent experience. Because of the dual status of the United States in the modern era – founded from an asymmetric conflict in the 18th century and patron of asymmetric wars since the 20th century – this study maintains an American emphasis, though situated in global context.

1.1 Definitions

All definitions have limits and exceptions. In the case of asymmetric warfare, the use of irregular methods in conventional interstate combat threatens to erode the distinctiveness of the concept. One may argue that “asymmetric war” is a redundant term, since all armed conflict contains an implicit quest for advantages over one’s opponent. In this vein, the ancient Chinese philosopher Sun Tzu elaborated on his famous “know your enemy” maxim with a comment on creating uneven conditions. Knowledge about opponents was valuable because it enabled generals to attack their enemies’ weak points with their own strengths.Footnote 6 Likewise, but in a modern context, Prussian theorist Carl von Clausewitz emphasized combatants’ universal striving to produce inequality on the battlefield. Clausewitz derided military writers who described “unilateral action” by individual commanders, since warfare was really a “continuous interaction of opposites,” not only in the fundamental sense of offense against defense, but of physical versus moral force, and scientific law versus genius that “rises above all rules.”Footnote 7 Genius, in this philosophy, consisted in locating the decisive point of a battle and creating a local asymmetry of force at that point. Clausewitz wrote at a watershed moment in the history of asymmetric warfare, after the 18th-century development of “partisans,” light, autonomous units that aided larger state-backed formations, and at the onset of the 19th-century “people’s wars” that plagued the Napoleonic occupations.Footnote 8 The uses of unconventional methods, within interstate warfare and on its margins, demonstrated the tendency of conflicts to develop an asymmetric character over time, as political and military leadership looked for ways to gain advantage and end the period of physical combat on favorable, indeed unanswerable, terms.

Astute readers may object here that the definition of asymmetry may be loosened and stretched to fit almost any conflict. After all, no two military forces can be perfectly alike. If one side has more weapons or more effective technology than the other, does that side not possess an asymmetric advantage? It may be true that differences in weapons or other forms of technology have persisted across all armed conflicts. But the distinctiveness of asymmetric warfare emerges when one side has access not only to a better type of firearms, but to a more general capability, such as intercontinental logistics, long-distance communications, artillery, naval, or air forces, which their enemies lack. These are not differences of degree but of kind. At the outset of asymmetric wars, an imbalance of military force drives further divergences of ideals, expressed in the acquisition of intelligence, the motivation of recruits and supporters, or the redefinition of events according to particular moral or legal norms. These imbalances of morale and intelligence help to explain how movements that are weak in their initial manifestations gain strength over the course of conflicts. An international tipping point often occurs in these wars, as successful insurgent or secessionist movements tend to gain the intervention of friendly external sponsors, who typically seek not to impose their own systems but to sow chaos in the hinterlands of their opponents. Thus, asymmetric wars are not those in which two or more governments use violence to impose their own rival forms of order. Rather, they are conflicts in which one side seeks to impose order while the other fights for a freedom of ideals incompatible with the policies of state forces. Over the centuries, these sentiments of liberty have been expressed in terms as diverse as individual rights, communal privileges, or religious purity.

It may be useful at this point to illustrate how the concept of asymmetry here defined will apply to specific examples of combat across modern history, which comprise the content of the following sections. In the next part, Section 2, the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763) becomes relevant for its contrast between British regular soldiers and Native American allies of the French, rather than the conventional battles fought by imperial troops in Europe and at Quebec. Likewise, the age of revolutions that followed is a subject for this volume not because of iconic American battles at Saratoga or Trenton, but due to the controversial role of militias in the war. The French experience during the era will concentrate on popular violence in the Vendée region (1793–1794) and during the Haitian revolution (1791–1804) rather than the Napoleonic battles among professional European armies at places like Austerlitz and Waterloo. Section 3 describes the long historical processes of colonization across the 19th and early 20th centuries, punctuated by wars fought by imperial armies of Britain, France, the United States, Russia, and the Netherlands against local indigenous polities. In Section 4, the world wars of the 20th century, like those of the 18th century, receive selective treatment as they apply to asymmetric warfare. The analysis touches on the First World War for its tribal and colonial rebellions in Africa and the Middle East rather than the industrial combat of the Western and Eastern European fronts. Asymmetric conflicts abounded during the interwar period, as well, and this volume highlights the roles of the Irish War for Independence (1920–1921) and the Second Italo-Ethiopian War (1935–1937) to reveal the limits of European imperial power. The Second World War enters as a topic of study not for its armored clashes between Germany and the Soviet Union, nor its naval battles between the United States and Japan, but for the new, fundamental asymmetry that the war created in terms of nuclear weapons, as well as the multitude of armed resistance groups that continued to fight hostile state forces into the “postwar” period in places such as China, Greece, and the Philippines. Asymmetric warfare proliferated in the neo-imperial age of Cold War superpower competition, described in Section 5. Special interest applies to combat in Korea, Vietnam, and Afghanistan that was waged between forces growing apart in their resources: elite, often clandestine, government units on one hand and people’s militias on the other. This trend toward mismatched combatants continued despite the end of the Cold War, due to the U.S.-led efforts in the Global War on Terrorism, which is the focus of Section 6. Though asymmetric wars often emerged on the peripheries of strong states and their spheres of influence, it should be clear from their frequent occurrence and lasting consequences that these conflicts were central to the modern state system.

Official attempts to define asymmetric warfare revived early in the 21st century, after what seemed to be decisive military operations by U.S.-led coalitions in Afghanistan and Iraq failed to bring about projected political results. The resulting attempts to create new doctrine offered a window into the military mindset. One U.S. army officer with recent combat experience defined asymmetric conflict in a 2006 policy paper as

population-centric, nontraditional warfare waged between a militarily superior power and one or more inferior powers, which encompasses all the following aspects: evaluating and defeating the asymmetric threat, conducting asymmetric operations, understanding cultural asymmetry and evaluating asymmetric cost.Footnote 9

This expansive practitioner’s definition continued to emphasize conventional military dimensions of conflict, as it placed the enemy threat first, a problem to be solved by operations. The specificity of this kind of warfare only becomes evident with the definition’s meta-operational categories of culture and cost. The official U.S. counterinsurgency doctrine issued in 2007 substituted “irregular” for “asymmetric” as a descriptor, but the concept is apparent in the manual’s section on the “nature of insurgency,” which reads: “Insurgent groups tend to adopt an irregular approach because they initially lack the resources required to directly confront the incumbent government in traditional warfare.”Footnote 10 Never mind that insurgency is as traditional a type of warfare as Americans can claim. The central concept remains fixed on imbalances, not only in resources and capabilities, but also in the intangibles of the conflict’s meaning amongst the population.

An asymmetric war may be defined in the most basic way as a conflict in which the differences between opponents cause them to operate in unique ways. French theorist David Galula used the analogy of a fight between a lion and a fly to illustrate the point; the fly cannot stomp on the lion, and the lion cannot fly. The fly has no hope of beating the lion outright, but it may buzz around the lion’s mane and drive it mad with exhaustion.Footnote 11 In these conflicts, combatants do not agree about the meaning of the conflict, are not armed with the same kinds of weapons, and do not behave alike.

The difficulty to categorize combat into neat boxes since the end of the Second World War has led some authors to reject the oft-cited trinity by which Clausewitz described the roles of the state, the military, and the people. Modern warfare, these critics allege, blends these categories to the point they are no longer useful. War has changed its fundamental nature because at a certain point, it began to result from the actions of irrational, non-state agents, rather than employed as an instrument of state policy.Footnote 12 Recent authors have instead proposed a “hybrid warfare” model, in which (legal) interstate conflict occurs alongside (illegal) insurgency waged by civilians. The scope of this work allows us to see that many wars throughout the modern era produced both symmetrical and asymmetrical theaters, as the First World War gave rise to trenches as well as tribal insurgencies. The recent emphasis on “lawfare,” or perceived unfairness of enemies who refuse to play by existing rules, betrays what one critic called “a convenient self-delusion” of the West: that wars can be limited by agreed-upon constraints.Footnote 13 The American defense community’s reaction to Chinese military officers’ publication of Unrestricted Warfare (1999), which called for economic, infrastructure, and social attacks in future conflicts, could only be so intense and negative if one ignored the various Cold War forms of soft power that Americans pursued with relish.Footnote 14 Indeed, asymmetric warfare, and the spilling over of military violence into economic and cultural conflict, have been a chronic condition for North Americans since the arrival of Europeans to the continent.

2 Asymmetry and Revolutions (1492–1815)

Revolutions bookended the early modern period, as first military and then political affairs underwent sweeping changes. The military revolutions that took place between the 14th and 16th centuries replaced small feudal armies with larger formations of professional troops, equipped with firearms and artillery pieces. European monarchs, to pay for their new militaries, increased burdens on their subjects, who eventually rebelled against their oppressors. The American, French, and Haitian political revolutions, results of 18th-century financial crises, proved successful against stronger imperial military forces. The wars opened opportunities for initially marginal groups to use narratives of human rights in their struggles against the dominant monarchical political order.

2.1 Revolutions in Military Affairs (RMA)

Historians have debated the nature and the scope of European military competition in the early modern period. What were the key innovations through which strong military states emerged in Sweden, Spain, France, Austria, and England? Participants in the RMA debate argue that the enormous expenses of defensive fortifications and wall-destroying artillery motivated the development of the fiscal-military state. In this new system, monarchs no longer raised war funds ad hoc from a collection of liege lords, but instead organized a bureaucratized tax apparatus. Armies dominated by noble cavalrymen paid in fief gave way to bourgeois armies of infantry, artillery, and engineers paid in cash or credit. Other historians noted that the fiscal-military state had its most significant applications in the building of transoceanic navies that European states – Portugal, Spain, France, and especially England – developed in competition with each other during the 16th and 17th centuries.Footnote 15

Whatever the specifics of the timing and causation of military revolutions, the voluminous debate addresses a basic question. How was it that a small contingent of Europeans deployed armies to America, Africa, and Asia, and not the other way around? The logic of empire depended on an asymmetric military situation, as imperial agents leveraged three unique capabilities: to come and go by sea, to bombard targets with naval forces, and to import firearms for combat on land.

Another significant aspect of asymmetry was disease, as Europeans brought “virgin soil epidemics” to the Americas. Military expeditions from Europe throughout the 16th and 17th centuries encountered indigenous societies reeling from demographic crises, though resistance movements soon adapted to the conditions of the creole societies that emerged. The European newcomers, by coincidence, had bypassed much of their own catastrophic plagues by the late 15th century. Thereafter, some European societies began to produce merchant classes and population surpluses that sought opportunities abroad. As these processes of demographic and economic expansion took place, military reformers adapted scientific discoveries into specific technologies in metallurgy for guns, chemistry for powder, and astronomy for trans-oceanic navigation.Footnote 16

Spanish and Portuguese military expeditions of the 15th and 16th centuries sought to overawe indigenous Americans into submission without the need for pitched battle. The conquistadors were so outnumbered by indigenous people that they could not so much conquer, as their label implied, as intervene into existing wars among American societies. The combination of the Iberians’ technology and their local allies’ intelligence wrought brutal results for those indigenous communities that resisted demands for their resources and their souls.Footnote 17 The Iberian destruction of American communities provoked a political propaganda campaign in England known as the Black Legend. The Franciscan priest Las Casas recorded the cruelty of the early American conquests, which served as justification for Britons to impinge on Spanish claims and, in theory, to create more benevolent colonial conditions.Footnote 18 From indigenous perspectives, there was often precious little difference in outcome among the various European colonial policies.

2.2 Ways of War

It is difficult to assess how the introduction of European technologies to America affected indigenous ways of war, though anthropologists and historians have offered several theories. The oldest scholarship on the subject argued that Native American warfare had been ceremonial in nature, and that the introduction of firearms transformed and intensified warfare.Footnote 19 More recent studies have made two significant revisions: first, that innovation was a two-way street; and second, that pre-contact American warfare had a robust tradition of lethality. The 17th-century English adapted indigenous tools and practices such as snowshoes, aimed fire, and “skulking” behind cover and concealment, rather than fighting in line formations on open fields.Footnote 20 Moreover, indigenous warfare did produce significant casualties in certain conditions. Native Americans of the eastern woodlands employed a “cutting off” way of war, rather than pitched battles, that minimized the likelihood of human losses while it maximized the social goals of warfare: taking captives, avenging past casualties, or raiding for material gain.

Though the means of cutting off enemies was scalable, from ambushes of a few travelers to attacks on large settlements, violence in indigenous American societies tended to be limited by several factors. Concepts of revenge were circumscribed: one or two enemies killed or captured could cover the losses of a previous campaign season. Europeans, on the other hand, often avenged the killings of individuals with escalation to the destruction of entire villages, as colonial English troops did at Mystic, Connecticut, in 1637 during the Pequot War. Furthermore, indigenous political leadership was more persuasive than coercive. War chiefs lacked their European counterparts’ capacity to summon troops by combinations of force and finance, so Native American coalitions relied on charisma and offers to win prestige; their war parties thus tended to be small and local in composition. Furthermore, war chiefs of the eastern woodlands shared power with “Peace Chiefs,” who dispatched resident aliens to neighboring communities as diplomats to prevent minor conflicts from escalating. In short, European firearms did not introduce lethality to Native American warfare, but they offered a new possibility for lethality during battles, after operational surprise had been lost.Footnote 21

2.3 The Seven Years’ War (1756–1763)

Throughout the 18th century, the French boasted an advantage over the British in terms of indigenous allies, who supplied the bulk of manpower and intelligence in North America. French success in recruiting indigenous peoples resulted from settler economics. By the 1750s, there were only fifty thousand French people on the continent, compared to one and a half million with ties to Britain. Indigenous societies identified the less intrusive of the rival empires and tended to support the French or remain neutral during conflicts between the Europeans. Native Americans used distinctive tactics in battle: the element of surprise through concealment, ambush, and aimed fire, a hit-and-run style of fighting “in the woods.” The British overcame their deficiencies in this mode of fighting as they learned to lean on their powerful navy to launch bombardments and amphibious landings, for which the French and their indigenous allies had little response.Footnote 22

In 1755, British General Edward Braddock arrived in America and attempted to build a road through the Appalachian forest to threaten French forts of the region. He soon found himself waylaid by indigenous fighters. Some historians have argued the British sent the wrong types of troops for this country, as regular heavy infantry plodded into ambushes set by nimbler foes. Colonel George Washington, a staff officer at the battle of Monongahela, disagreed and blamed the loss on a lack of nerve within Braddock’s formations. Washington’s lesson was not that the British should have been more prepared for irregular light troops, but that they should have been more regular and disciplined in their training.Footnote 23 Braddock’s 44th and 48th regiments of foot had been dispersed for constabulary duty in Ireland before their voyage to America. Both units were understrength by about half and had to recruit raw soldiers just before embarkation. The French and their indigenous allies, after days of careful scouting, performed a series of decentralized encirclements of the British line. The documentary record of British survivors indicates the psychological effects of the indigenous fighters’ rapid movement, as well as the terrifying sounds of war cries and expectations of mutilation upon captivity. The tactical reversal turned into a rout.Footnote 24

Following their defeat at the outset of combat on North America, the British military redeemed itself over the ensuing course of the Seven Years’ War. Three years after the disaster on the Monongahela, a new column under Colonel Henri Bouquet succeeded where Braddock had failed, as troops built a road from the western British settlements to Fort Duquesne. The British successes took place in the absence of France’s indigenous allies, most of whom had left the war by the end of 1758. Bouquet, whose previous experience had been limited to Europe, drew lessons from what he called a “new kind of war.”Footnote 25 In a pamphlet entitled “Reflections on the War with the Savages of North America,” he noted that Europeans were used to fighting in a “cultivated and inhabited” land, which featured roads, armaments magazines, and hospitals, as well as “a generous enemy to yield to” in normal conditions. On the other hand, Bouquet emphasized:

In an American campaign, everything is terrible; the face of the country, the climate, the enemy. There is no refreshment for the healthy, nor relief for the sick. A vast, unhospitable desart, unsafe and treacherous, surrounds them, where victories are not decisive, but defeats are ruinous; and simple death is the least misfortune which can happen to them.

A lack of intelligence made the hostile environment still more forbidding. Since the indigenous fighters seemed to compound their advantages in intelligence with an ability to fight “scattered” rather than in a “compact body,” Bouquet suggested three maxims for a European army engaged in America. He counseled they be “lightly cloathed, armed and accoutered,” that they avoid “close order” formations, and that they learn to operate “with great rapidity,” to address the Native Americans’ skill at moving through the forest.Footnote 26

The frustrations brought on by indigenous soldiers’ mobility led Bouquet to seek extraordinary methods. In a 1764 letter to William Penn, Bouquet asked not only for a unit of “light horse,” which had served well during the Forbes expedition of 1758, but also one hundred “proper Hounds,” to be imported from Britain with their handlers. Bouquet speculated that the dogs would be useful to “discover the Ambushes of the Enemy, and direct the Pursuit.”Footnote 27 There was no indication in subsequent correspondence that the animals supplied the benefits Bouquet imagined, but his logic revealed an attempt to overcome the mobility gap with technical solutions imported from the metropole.

The most heinous example of this trend, popularized to the point of cliché, was British General Jeffery Amherst’s order to gift blankets discarded by a smallpox hospital to Shawnee adversaries who besieged Fort Pitt in 1763. On that occasion, Amherst counseled his subordinate Bouquet to use not only biological warfare, but animals used for hunting, and “Every Strategem in our power to Reduce them.”Footnote 28 The military effectiveness of the blankets, as with the dogs, was unclear. The more significant factor that ended Pontiac’s rebellion was the British diplomatic promise to keep settlers east of a Proclamation line that ran along the peaks of the Appalachian Mountains. Bouquet demonstrated the power of letters to government officials. His epistolary efforts to bring about the Proclamation revealed the early importance of communications media for the building of coalitions and consensus to end asymmetric warfare.Footnote 29

2.4 The Age of Revolutions

Rebellions in British North America, France, and Haiti resulted in extended periods of warfare. According to some historians, these conflicts introduced a new type of conflict fought by a new class of soldier: “total war” waged by fighters who rallied to popular, idealistic causes. The levée en masse in France forms the paradigm for this concept of novelty in warfare during the Age of Revolutions.Footnote 30 But claims that the political upheavals of the late 18th century brought about total war have obscured a continuity from the colonial era: asymmetric conflicts had been total to the colonized side throughout the previous centuries.

The Age of Revolutions represented a rupture in political, rather than military, history, as the trends of early modern “military revolutions” continued with the development of fiscal-military states. American rebel leader George Washington, for example, sought to emulate the army of the British Empire rather than to innovate beyond it. Revolutionary and Napoleonic-era soldiers, as their letters demonstrate, were no more idealistic than those who served the French monarchy had been, but the new state recruited them faster and from a larger social pool. The biggest difference between Napoleon’s armies and those of his ancien régime predecessors was size, rather than methods or equipment.Footnote 31 New empires across the Atlantic oppressed those outside the body politic on par with royalist rivals, though lines of exclusion defined status more by race and gender than class, as in the old monarchies. The end of the 18th century witnessed a proliferation, rather than the introduction, of “citizen-soldier” militias, rapidly formed, light infantry skirmishers that had been long been commonplace on battlefields in Europe and America.Footnote 32

2.4.1 The American Revolution

The U.S. War for Independence began with battles at two small Massachusetts towns in April 1775, over a year before the rebels declared political independence from the British Empire. Social protest, however, had been brewing in North America since the end of the Seven Years’ War. The financial burdens of the late conflict against the French fell unfairly, some began to claim, on those without representation in Parliament. Though popular narratives tended to emphasize the actions of rebel leader Samuel Adams and his associates in the Sons of Liberty, an intelligence network designed to stymie oppressive British governance, political violence during the 1760s also took place between rival groups of colonists. Fighting broke out between coastal elites and a variety of rural leveling protest movements, such as the Regulators of North Carolina. Moreover, the idealism that men such as Samuel Adams and his cousin John lent to the colonial insurgency has overshadowed the material interests in question. Colonists tended to care less about political abstractions and more about discrete policies that governed western land and British credit. These issues, under the guise of “liberty,” drove Virginia’s gentry into rebellion by 1776, to the benefit of the Patriot movement in New England.Footnote 33

American rebels fought the first three years of the conflict at decided material disadvantages. Washington preferred to correct the balance by making the American rebels look and act more like their British foes, to train them according to the dictates of Prussian officer Baron von Steuben, in the hopes of waging offensive operations against other regulars.Footnote 34 Yet Washington also recognized the reality that he had to wage a defensive conflict fought for the most part by “irregular” or short-time troops. Therefore, he called on Congress at the end of 1776 to create a “respectable” army that would be “competent to every exigency,” both grande guerre against British regulars and petite guerre against Native Americans and Loyalist militias. One of Washington’s top subordinates, General Charles Lee, disagreed and thought the American rebels should lean into potential asymmetric advantages. Lee raised the possibility of dispersing squads of regulars among the towns and farms, to lead partisans and drag the British into a bloodier civil war. Except in small pockets of the American South later in the war, Lee’s vision found little support among the rebel leadership.Footnote 35

In strategic terms, the colonists’ asymmetric war against the British Empire became symmetrical after the French alliance of 1778. With this diplomatic achievement, Americans gained the capability to counter the British navy and to pay soldiers on the brink of desertion. These elements came together during the decisive 1781 Yorktown campaign, fought by a combined Franco-American army and enabled by a French loan and naval blockade.Footnote 36 Rather than foreign aid, the popular mythology of the “minuteman” held that the common American citizen-soldier had stymied the regular British redcoats and forced the empire to abandon its reconquest of America. This populist-patriotic narrative omits Washington’s frequent quips about the militia’s lack of dependability, that to rely on them was to rest “on a broken staff,” that they were “ready to fly from their own Shadows,” and amounted to only the “garnish of the table” compared to the regulars of the Continental Army and their French allies.Footnote 37 While there were some instances of successful militia action, they tended to result from charismatic small unit leadership, as in the case of “Swamp Fox” Francis Marion.Footnote 38 As a whole, militia performance was variable, and their short enlistments meant they tended more toward waste and loss than regulars.

But militias did lend some benefits to Washington. First, they comprised the bulk of his forces – anywhere from three quarters to 90 percent of troops in the field at any given time. Militiamen, even when they were not active on campaign, served as a network of intelligence and communication that favored the Patriots, and their presence dissuaded Loyalists from organizing a counterinsurgency. British soldiers became frustrated with parsing out militia leadership from bandits and criminals. When British regulars acted harshly against these figures, the popular backlash hurt the cause of reintegrating rebels back into the empire.Footnote 39

Washington’s army, rather than augment partisan warfare, became more professional over time. The course of Daniel Morgan’s career was illustrative in this respect. His rifle companies that arrived at Boston from the Pennsylvania woods performed poorly in early skirmishes. But by the battle of Cowpens in 1781, Morgan understood how to coordinate the use of militias as sharpshooters and light infantry scouts on the margins of regular infantry formations. Morgan’s units represented, per historian John Hall, “the maturation of the American ranger tradition,” from “irregular antecedents” to “elite regulars.”Footnote 40

2.4.2 The French Revolution

Across the Atlantic, the American War for Independence shook French finances. The debt that King Louis XVI’s government incurred to support the war effort proved too much to handle, as the French state was already burdened by the costs of the recent Seven Years’ War. The failure of the fiscal-military state, rather than desperate class warfare waged by peasants, opened the door to the French Revolution, led in its early years by “enlightened” nobles. When the revolution became more radical with the execution of the royals in 1793, France fractured into civil war.

The most intense asymmetric conflict emerged in the Vendée, a coastal region south of the Loire valley. Resentments had long simmered among religious, rural inhabitants against the revolutionaries in Paris, and open rebellion broke out with a request for troops in March. It was one thing to become citizens of a secular republic and watch it attack God and King from afar, and still another to be asked to fight for it.Footnote 41 Rather than submit to a draft, thousands of young men organized a White Catholic force to oppose the revolutionary, Blue-clad troops.

After conventional attempts against rebels failed, radical followers of Jacques-Rene Hébert in the National Convention demanded an intensification of violence. General Louis-Marie Turreau traversed the territory with 3,000 men, who marched through the Vendée in a systematic way, according to Convention orders of August 1793, “to exterminate this rebel race, to destroy their hiding-places, to burn their forests, to cut down their crops.” These orders became irrelevant after Republican victories broke up the rebel army in battles during October and December, yet Turreau persisted in his “military promenade” across the defenseless population in the early months of 1794. He claimed afterward to have been less afraid of local insurgents than of his political overlords, the Hébertistes known for sending generals who lacked ambition to the guillotine. By 1795, when the new French commander Lazare Hoche turned to a more conciliatory pacification effort, a quarter of the region’s population had been killed.Footnote 42

Of course, there had been many previous examples of violence against noncombatants in French history: the Camisard revolt in the early 18th century, religious wars of the 16th century, and the crusade against Cathar heretics before that. But the French monarchs and their military captains tended to use war as a limited, legal means of solving political problems. The Revolutionary government transformed warfare by seeking an escalation of participation from society. Opponents of the new regime, based on Enlightenment principles assumed to be universal, could only be “enemies of liberty,” per National Convention deputy Maximilien Robespierre, “monsters of the universe.” Warfare was no longer the recourse of nobles to resolve petty disputes; it had been reimagined as a fight to the death between peoples.Footnote 43 As the revolutionaries ceded their chaotic reign to the stability of dictatorship under Napoleon, the emperor inherited their concept of greater societal participation in war.

Napoleon’s dazzling battlefield victories have overshadowed the extent to which peasant rebellions laid low his empire. The term “guerrilla” (small warrior) first emerged in Napoleonic Spain to describe the fanatical attacks of peasants and religious leaders who at times cooperated with the Spanish government-in-exile, and still less often with foreign allies in Britain and Portugal. It was the ideological commitment of the fighters (not merely opportunistic criminals or rioters) and their lack of direct connection to a sovereign patron that separated the Spanish insurgents from predecessors. Their role was to oppose legal power, rather than to act as an auxiliary of it, as partisan units had during the Seven Years’ War.Footnote 44

Napoleon’s short-lived occupations of Spain, Italy, and various German territories demonstrated the significance of religion as a martial motivation, as faith engendered feelings of national difference in opposition to the Revolutionary concepts of universality and rational bureaucracy. Thus, national secessionist sentiment was less the cause of revolutions as a result of the chaos that war and occupation brought about. The nation became the idiom of insurgency for those opposed to more intrusive empires. The printing press became a weapon, as revolutionaries saw their role as educating the people about the as-yet-unrealized nation.Footnote 45

2.4.3 The Haitian Revolution

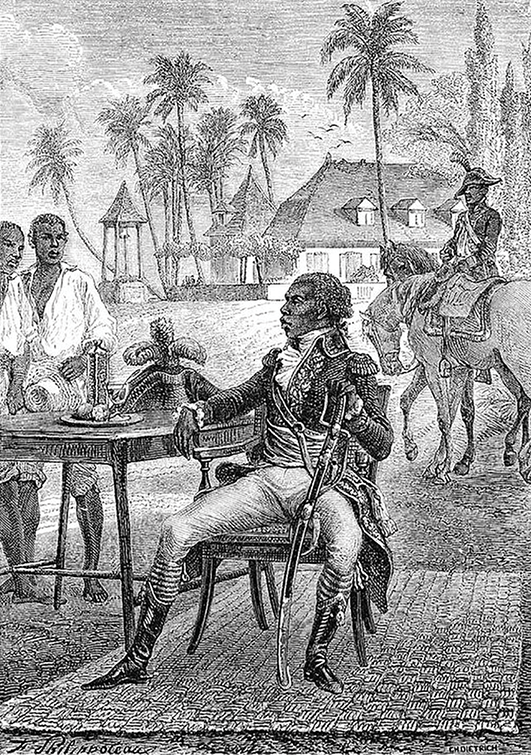

Nowhere in the Atlantic was the rupture from colony to nation more sudden and painful than in French Saint-Domingue, reborn as the Empire of Haiti. A population of 400,000 enslaved people rebelled against some 50,000 white and mixed-race elites, and the pent-up resentments of slavery fueled atrocities. Some owners exacerbated the destruction by arming their laborers, out of fear their plantations would be overrun in the revolutionary struggle between republicans and royalists. A major turning point in the rebellion came in 1793, when republican agents promised freedom to former slaves in exchange for military service. Toussaint L’Ouverture and a group of fellow generals gained power by subverting the royalist hierarchy, and they pledged loyalty to the new revolutionary French government.Footnote 46

But when Napoleon came to power, he was disturbed by the relative independence of the former plantation overseer L’Ouverture, depicted in Figure 2. The emperor deployed his brother-in-law, General Charles Leclerc, to overthrow the territory’s leadership. As French reinforcements approached the island, L’Ouverture reminded a subordinate of their asymmetric means of defense, as he counseled, “We have no other resource than destruction and fire. Bear in mind that the soil bathed with our sweat must not furnish our enemies with the smallest sustenance.”Footnote 47 The French repaid atrocity with atrocity. Leclerc ordered troops to “destroy all the blacks of the mountains – men and women – and spare only children under twelve years of age.”Footnote 48 One of his subordinates, by contrast, advocated a departure from harsh French practices, which included crucifixion and feeding to dogs. Bertrand Clauzel, in a more productive course, bought up plantations “to engage [the inhabitants] in reconstruction,” in a work-for-loyalty program that became standard practice much later, during 20th- and 21st-century counterinsurgencies.Footnote 49 Despite promising signs for the project, Clauzel did not remain long enough to see lasting results. Within a month of his departure, workers abandoned their fields and rejoined the rebellion. The following year, they achieved their independence in the first successful revolt of enslaved people in the Atlantic world.

Figure 2 Engraving of Toussaint L’Ouverture by Felix Philippoteaux, 1870, Wikimedia Commons

2.4.4 Revolutionary Coda: War of 1812

The pressures of war against Napoleonic France pushed the British to impress, or abduct, American sailors at sea. The British claimed that their captives were in fact royal subjects who had fled service in U.S. ports. Nevertheless, the slight to American sovereignty, along with British refusals to cede fortifications in the West, led the U.S. Congress to declare war. The Americans planned, as in the War for Independence, on an overland strategy to conquer Canada, but the conflict turned out to be a battle of survival for the experimental republican government. Even in the symmetrical theaters against “civilized” opponents, the war brought atrocities and unconventional tactics: the burning of capitals York and Washington, the execution of prisoners, and the British enticement of enslaved people throughout the Chesapeake Bay region to serve as an “internal enemy.”Footnote 50 But while the U.S. army developed into more regular formations under General Winfield Scott in the north, General Andrew Jackson followed a different course in the southern theater, as he intervened in the Creek Civil War.

The famous U.S. victory at the Battle of New Orleans (1815) overshadowed the historical importance of Jackson’s previous battle at Horseshoe Bend (Tohopeka, 1814), which he viewed as “avenging” the massacre of white settlers and their indigenous allies at Fort Mims. Jackson led a collection of regular infantry, Tennessee militia, and Native American allies on a typical “feed fight” expedition, in which troops burned crops and settlements until they hemmed in the “Red Stick” Creek resistance movement to a narrow river bend. Jackson’s troops were ruthless in the ensuing battle, as they massacred some 800 Creek fighters, along with many women, at a loss of only 70 to their own side. Jackson spared neither his defeated foe nor his own Lower Creek allies. After the battle, the Creek confederation ceded land that became half the state of Alabama and much of Georgia to the United States. Some of the surviving “Red Stick” Creek families fled south to Florida, where they would participate in the Second Seminole War (1835–1842) during Jackson’s presidency.Footnote 51

The military campaigns that Jackson led during the War of 1812 and the subsequent First Seminole War (1818–1819) opened up the Old Southwest to settlement by white planters, which allowed the creation of the Cotton Kingdom and generated the rationale for his later Indian Removal legislation. Jackson had become the latest in a series of “men on horseback,” leaders such as Washington, Napoleon, and L’Ouverture, whose military exploits propelled them to become heads of state. The imposing cults of personality they cultivated served to overawe colonized opponents and loyal citizens alike.Footnote 52 In the Age of Revolutions, participation in the asymmetric warfare of imperial forces became pathways to fame and power.

Throughout the 19th century, European politics underwent a gradual shift from chaotic revolutions to the management of relative stability. As a balance of power settled on the continent, the culture of empire shifted as well, from an Enlightenment ethos that opened possibilities of multicultural cooperation, to exclusionary national myths and scientific racism. And with the dampening of chances for war on the European continent itself, struggles shifted to competition for colonies overseas. Stronger central governments aided and benefited from the development of new technologies: the railroad and steamship, telegraphs, and artillery pieces that gave the European empires advantages in logistics and firepower over colonial resistance movements.

3 Asymmetry and Empires (1815–1914)

Despite the political challenges to the British and French Empires that proliferated during the Age of Revolutions, both systems proved their resiliency throughout the 19th century. The old empires of the North Atlantic gained in power despite the emergence of new imperial rivals in the United States and Germany by the end of the century. In this era of global imperial expansion, asymmetric conflicts of American Indian Removal took place alongside French and British wars in Africa, Asia, and Oceania. In each case, historians have debated the importance of settlers to empires of the era.

3.1 Settler Colonialism

Demography played variable roles for colonial populations. Malthusian fears of growing and desperate European underclasses found relief in imperial policies that encouraged settlement in overseas (or in the U.S. case, western overland) territories. The importance of civilian migrants varied among the empires. Even within empires, some colonies possessed different amounts of political sway over home governments. Per historian James Belich, a crucial factor in the significance of settler populations to colonies was the initial presence of metropolitan women, who became “founding mothers.”Footnote 53 For 19th-century British and American cases, large migrant populations weighed heavily on imperial policy. In the French case, until the end of the 19th century, it was the military instead that led the colonial effort.

Settlers sought indigenous peoples’ land and had no use for their labor, unlike imperial agents of the military and trading companies in need of colonized peoples’ cooperation. In places like Australia, where the British neglected to send regular troops for much of the colony’s history (similar conditions existed in U.S. California and Oregon territories), settler colonialism has a great deal of explanatory power. In places like Florida, where federal military agents predominated over a weak territorial government, conditions do not follow the theory’s logic as well.Footnote 54 In North Africa, which became integrated as French départements led by a military governor, and where settlers never became the dominant proportion of the population, the theory seems to explain still less.Footnote 55 Governments throughout the 19th-century Atlantic publicized their support to settlement from the metropole in order to distinguish their own allegedly virtuous colonization from previous efforts of extractive monarchical conquest. But cooperation between states and settlers within colonies was often aspirational rather than real, since the two groups had conflicts of interest with regard to exploitation versus elimination of indigenous peoples.

Many asymmetric aspects affected imperial wars of the 19th century, but factors of numerical strength and technology did not always favor the Euro-Americans. During the Second Seminole War (1835–1842), the United States deployed to Florida over 5,000 regular troops, or almost twice the total population of indigenous people who remained in the territory at the time. But the opposite situation applied for the British and French in Africa and Asia, where they confronted local governments with huge numerical advantages. In terms of technology, though the Seminoles lacked cannons and steamboats, trade relationships with the Spanish equipped them with rifles that matched contemporary U.S. army small arms.Footnote 56 During contemporary campaigns in India, Mughal and Sikh princes possessed heavy guns that outclassed those the British could carry with their formations. It was only at the end of this era that the Maxim gun, indirect-fire artillery, and (still later) airplanes provided clear advantages to imperial weaponry in the colonies.Footnote 57

While numbers and weapons fluctuated in significance across imperial contexts, empires did maintain the strategic advantage of logistic resupply, now enhanced by new technologies of steam ships, railroads, and the telegraph. These innovations represented a broader trend of “scientific” warfare, a legacy of the polytechnic, engineering education that produced Napoleon and his generals, and which spread to the other Euro-American states in the generation that succeeded them.Footnote 58

3.2 Wars of American Expansion

Science played a major role in American Indian Removal, a generations-long process. True, Jackson’s operations in the Creek Civil War (1814) and the First Seminole War (1818–1819) had more to do with “First Way of War” attacks on crops and settlements than principles of contemporary science.Footnote 59 But the generation of regular officers who came of age during the War of 1812 often rejected Jackson’s brand of fighting in favor of one that leveraged technology and diplomacy to minimize violence in Indian Country rather than escalate it.Footnote 60 This was the pattern in Florida, where regulars concentrated. But the U.S. army was tiny, no more than 12,000 soldiers total, in light of the continental scale of federal U.S. claims. As a result, endemic skirmishes took place between settlers and indigenous people in western territories, where regulars were mostly absent.

In Florida, the few settlers who migrated from the United States crowded into plantations in the northern third of the territory, leaving millions of acres of Everglades swamp to the indigenous resistance. During the Second Seminole War (1835–1842), indigenous resistance fighters wielded an asymmetric advantage of intelligence about the local topography, which allowed them to evade U.S. patrols and choose the timing of the few battles of the war. Commanding General Thomas Jesup grew so frustrated with the perceived deceits of his enemies that he ordered subordinates to capture resistance leader Osceola under the false auspices of a “white flag” talk. The deceptive tactic became politicized, as Whig Party officials opposed to the reckless expansion of Jackson’s faction used the incident to castigate the Democrats who ran the war. The unpopular conflict ended after seven years, even as several communities of Seminoles remained in Florida.Footnote 61

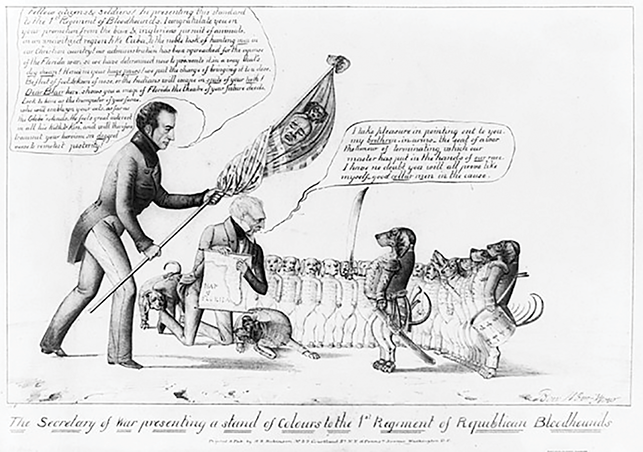

The biggest tactical problem for U.S. agents during the war was one of mobility. American forces attempted to overcome their lack of speed through the creation of a regular cavalry unit, the importation of “bloodhound” dogs from Cuba, and the invention of an improvised explosive device (IED). This latter innovation was the product of infantry Captain Gabriel Rains, who built two prototypes out of howitzer shells, some powder and metal fragments, and old military uniforms to entice Native Americans to set off the detonator. The IED, like the bloodhounds satirized in Figure 3, failed to have any effect on the course of the war, even at the tactical level, but these tactics demonstrated the range of adaptations, along with the steamboat, by which U.S. forces attempted to close the mobility gap.Footnote 62

Figure 3 Napoleon Sarony, “Secretary of War presenting colors to a Regiment of Bloodhounds,” 1840, Wikimedia Commons

The Mexican-American War (1846–1848) arose over a boundary dispute in Texas, a former Mexican territory recently annexed by the United States. Though combatants from both republics fought campaigns on conventional lines, two important asymmetric aspects affected the contours of the war. First, U.S. armies that invaded Mexico found its northern territories depopulated by years of Comanche raids; local populations had become disillusioned with federal politicians in Mexico City as a result. Second, following defeat of its Mexican counterpart, the U.S. army attempted occupation of an extensive territory. General Winfield Scott, wary of recent Napoleonic troubles in Spain, developed what might be called the counterinsurgency playbook, as he advised subordinates to protect Mexican property, respect the Catholic Church, keep indigenous officials at their posts, reestablish public services such as schools and hospitals, and distribute rations to the poor. All of these efforts combined to marginalize insurgents.Footnote 63

The Mexican War land cession provoked tensions on the issue of slavery that led to the American Civil War (1861–1865), another conflict in which guerrilla fighting constituted a significant aspect. As much as one third of the entire Union army had to garrison regions of questionable loyalty in Missouri, Kentucky, and Maryland. The rebels, too, struggled to deal with Unionist sabotage in much of Appalachia. The Confederate States of America (CSA) created light cavalry “Partisan Ranger” units, which raised their own recruits and supplies, lived among the people, and thus blurred the line between public service and criminality. The Union government adopted a legal code developed by Francis Lieber (1863) to define public warfare as fought between states and distinct from private war, waged by independent “bushwhackers” without official connection to a government and thus liable to summary execution rather than captivity as prisoners of war.Footnote 64

The problems of distinguishing between the legitimate partisans and guerrillas, war-rebels, and other bushwhackers led some Union commanders to “hard war” policies: the execution of prisoners, deportation of rebellious populations, and destruction of private property. General William T. Sherman, a veteran of the Second Seminole War, used his forces to target the upper-class slaveholders who had led the secession movement. Other Union officers created specialized counterguerrilla units that emphasized the collection of local intelligence, rapid movement including by night, and ambush tactics. Insurgency continued during the Union’s occupation of the defeated CSA during the years of Reconstruction, though usually to enforce a race-based social code rather than to challenge the political reintegration of the states into the Union.Footnote 65

3.3 France and North Africa

The U.S. military of the early 19th century reached out to learn from the French, who were engaged in their own war of southern expansion in North Africa. Political theorist Alexis de Tocqueville, among others, argued the only way to “win” a colonial war was to export masses of settlers from France. But Algeria, like Florida, proved an unpopular place for metropolitan migrants. French commander Thomas-Robert Bugeaud proposed to wage war by “sword and plow,” with the creation of military colonies adjacent to settlers, to be led by veterans after their periods of service in Africa. These experiments tended to fail in practice, and the French government abandoned the interior of the colony for long periods through the 1830s and 1840s to hole up in coastal enclaves.Footnote 66

Abd el Kader, the most effective leader of North African resistance, learned to incorporate more conventional elements of combat as the years of conflict passed. Unlike Osceola in Florida, who led perhaps a few hundred soldiers at the height of his rebellion, Abd el Kader led thousands of infantrymen organized into battalions, recruited tens of thousands more cavalrymen through tribal militia, and even culled French deserters into specialized units of engineering, logistics, and artillery. But like Osceola and his traditionalist, anti-imperial religious rhetoric, the “iron Emir” was a master of political action. In North Africa, the call to jihad had been well rehearsed, but Abd el Kader further benefited from recent examples of French atrocity to persuade locals to aid his troops and turn their backs on the wealthy sheiks of the colonial administration. French General Bugeaud’s war of conquest in Algeria, like Jesup’s in Florida, was a stop-and-start affair, marked by episodes of atrocity alongside those of negotiation. French colonial historians have described separate phases of assimilation, association, and extermination in discrete periods, but military records reveal that all three modes occurred throughout the French colonial era. Local conditions in Africa had more of an effect on the likelihood of French atrocities at any given time than did policies from Paris.Footnote 67

Historians have singled out Bugeaud as a special proponent of razzia, raids on indigenous settlements and herds, but his predecessors in command had not hesitated to order these practices, as well. What separated Bugeaud from the other commanders was his outspokenness in the press and his self-promotion as a military innovator. Bugeaud’s reforms in Algeria were operational rather than cultural. He counseled subordinates to create “flying columns” without heavy guns and baggage, but he had little effect on mindsets within the Armée d’Afrique, which was already an aggressive and unruly force by the late 1830s. The difference between fighting in Europe and Africa, in Bugeaud’s mind, had less to do with the humanity of his opponents, and more with divergent centers of gravity. In Europe, these comprised large military units and towns, whereas in North Africa, herds and crops became primary targets. On both continents, French commanders engaged noncombatants with violence when they interfered with the safety or political ends of occupying military forces. After all, Bugeaud and his generation of French officers had been introduced to warfare through sieges and bombardments against Spanish settlements suspected of harboring guerrillas.Footnote 68

3.4 Britain and South Africa

General Harry Smith, like Andrew Jackson and Thomas-Robert Bugeaud, began his military career during the Napoleonic Era. He contrasted his experiences in America, which he denigrated as “milito-nautico-guerrilla-plundering warfare,” with examples of “humane warfare” under the Duke of Wellington against France. Smith was disturbed by orders to burn the American capital, a practice which he claimed to be suitable only for Native American warfare. After this unsettling debut, Smith went on to fight in India and South Africa.Footnote 69 Though the Indian campaigns took place between two professional armies, each equipped with cavalry and artillery, the British Xhosa Wars (1811–1879) of South Africa were interminable conflicts of rebellion and counterinsurgency, periods of diplomacy interrupted by massacres, much like the American wars of Indian Removal and the French conquest of North Africa.

Wars of the Cape began with British attempts to protect shipping to India around the time of the French Revolution. The first attempts at settlement began only later, in 1820. The correspondence of British imperial officials reveals that they used the defense of settlers as a mere excuse for their true purposes: to gain more resources from London and extend their mandates over indigenous land.Footnote 70 Settlers’ critiques of indigenous Africans focused on economic aspects of property and labor; descriptors such as “theivish” and “indolent” are rife in their communications. But military officers’ criticisms of indigenous people as ungovernable, “treacherous” or “barbaric,” proved more alarming in London. British military officials succeeded in growing their power relative to civil authorities through calls to war. Fewer than 2,000 British regulars took part in the Sixth War during the mid-1830s, which Smith waged as military commander against one Xhosa king. During the Eighth War of the 1850s, Smith oversaw 8,000 regular soldiers as military governor, as they countered a more general rebellion in the newly established territory of British Kaffiria. The British in South Africa relied on well-established tropes of “savagery” to undermine the authority of indigenous leaders and justify colonial dispossession.Footnote 71

The British used a divide-and-conquer strategy to augment their numbers and close the intelligence gap with indigenous people, as did the Americans across the Atlantic. In Florida, U.S. commanders employed liberty diplomacy to attract Black Seminoles, people who had escaped slavery and lived among the Seminoles, to serve as interpreters, guides, and porters for the army in exchange for resettlement as freemen in the West.Footnote 72 In South Africa, British leaders encouraged the defection of the minority Fingo people to scout rebel positions, in some cases to serve as a “decoy” to draw out potential ambushers. Not only did the British consider Fingo fighters more expendable, but indigenous allies required no cash as colonial troops did, since they accepted captured cattle and other plunder as compensation. Moreover, British officials assessed that the Fingo people were accustomed to the kind of scorched-earth tactics they sought to employ, though Britons proved they, too, could employ harsh measures.Footnote 73

3.5 Russia and Central Asia

For centuries, the Russian empire maintained a consistent southern border that stretched eastward from the Caspian Sea. But from the 1830s until the end of the century, the Tsarist government expanded to include 1.5 million square miles of territory in Central Asia and more than 6 million new subjects, almost all of whom practiced the Muslim faith. Why did the Russians expand so rapidly? British observers often answered by pointing to the “natural” aggression of their imperial opponents. Russian historians, on the other hand, described the economic resources that pulled the empire further south. The most recent scholarly works on the topic, however, reject any overarching political or economic “grand strategy” in favor of the complex interactions between officials in St. Petersburg, ambitious Russian agents “on the spot,” Central Asian rulers, and “disobedient” local peoples.Footnote 74

The Russian army benefited from a near-monopoly on infantry and artillery forces in the region throughout the decades of conquest. Their problems against indigenous irregular cavalry, which resembled the Russians’ own Cossacks, were more logistical than tactical. Massive convoys of camels perished during attempts to cross the vast deserts of the region. The Russians, through a series of sieges on cities and fortresses, kept their own casualties remarkably low. One contemporary historian recorded the total killed and wounded from 1853 to 1881 in Central Asia at just over 3,000, or fewer than the Russian losses in one day at the battle of the Alma River during the Crimean War.

Operations in the Semirechye (Jetisu) region exhibited parallels with the contemporaneous French campaigns in North Africa. Both conquests began with small-scale operations against raiders on the territory of an indigenous Muslim Empire. Whereas the French in North Africa undercut Ottoman authorities, the Russians in Semirechye contested the Kokand Khanate’s claims to authority over restive Kazakh and Kyrgyz nobles. The Russian analog to the French Bugeaud was General Gerasim Kolpakovskii, who began his career in the enlisted ranks and crushed a revolt in Europe before his deployment to the Ala-Tau region. Kolpakovskii, like Bugeaud, sought to secure military gains with the importation of settlers and crops from Europe. These Russian experiments, as with the French ones, resulted in little migration until the region’s connection to Russia’s network of railroads. The site of the city Almaty comprised a sparse military fortification for decades before it finally cultivated a population of more than 20,000 by the end of the 19th century.Footnote 75

One of the region’s most significant and mythologized campaigns was the Russian occupation of Tashkent. In June 1865, General Mikhail G. Chernyaev led a force of fewer than 2,000 men to take the largest city of the region, populated by more than 100,000, with a loss of just 25 soldiers killed. The event was typical of the “disobedience” thesis of Russian military history, in which bureaucrats issued vague or contradicting orders but accepted the successes of “rogue generals” in the field. Recent research argues that the Russian metropolitan elites may have disagreed with the timing of Chernyaev’s actions, and they disdained his initial failure to take the city, but their goals for Russian expansion aligned with those of the man on the spot. Chernyaev was sensitive to the cultural differences of the newest Russian subjects, as he worked through the local ulama to ensure post-battle administration and to reassure the people of Tashkent that their religious values were safe under Russian patronage. His actions indicated contrasting motivations for Russians in Central Asia, as they claimed to “civilize” indigenous inhabitants, while at the same time governing with as light a touch as possible.Footnote 76

The Russians, along with the other European empires, committed atrocities during their imperial campaigns. Transcaspia, in the borderlands of Qajar Persia, became the particular subject of international scandal due to the leadership of General Mikhail Skobelev, whom even a reserved historian of Russia labeled a “revolting sadist.” After a brutal “pacification” campaign in Ferghana in 1875–1876, Skobelev encouraged the massacre of 8,000 Turkmen, including many women and children, during their attempts to flee the fortress of Goek Tepe in January 1881. Yet historian Alexander Morrison concludes that Skobelev’s leadership alone cannot explain the growing tendency of Russians to massacre the inhabitants of the cities they conquered toward the end of the 19th century, as the forces became more asymmetric over time. Morrison suggests some “clear parallels” to the conditions of French Algeria in the 19th century, as he notes, “the reputation shared by Turkmen and the Touareg for savagery, insolence, and slave-raiding,” which drew the disgust and extreme violence of invading European soldiers. In most places, there was little resistance to the Russian Empire after its initial conquest, as local leaders retained their administrative roles and the Russians contented themselves with more or less indirect rule. Only 30,000 imperial troops administered the entire region in the last decades of the 19th century. Violence did not arrive for most Central Asian peoples until European settlement accelerated in the early 20th century, following the revolt of the summer of 1916.Footnote 77

3.6 French “Civilizing Missions”

As the 19th century turned into the 20th, European empires began to revise the logic for their military affairs. Imperialists started to justify their campaigns by pointing to alleged benefits of their system for the people of the colonies, themselves, as they added to older arguments about economics or the glory of the metropole. The French use of the term mission civilisatrice dated to 1840, a few years before the American term “Manifest Destiny” appeared. In the French case, a contributor to the Geographic Society posited, “Expatriation is an economic need, a political necessity, a civilizing progress.”Footnote 78 Though French observers often contrasted their universalist assimilation project as distinct from the Anglo-Saxon methods of expulsion and extermination, in practice all imperial campaigns contained a chaotic mix of cultural attraction and economic opportunity, backed by ready resorts to violence.

French Generals Joseph Gallieni and Hubert Lyautey became preeminent theorists of counterinsurgency warfare. They sought to reframe colonial war at the end of the 19th century as a beneficent enterprise, rather than the brute conquest of previous generations. The officers coined the phrase “hearts and minds” to describe the project of political and economic suasion that they practiced in Indochina to prevent atrocities and minimize local resistance to the French Empire.Footnote 79 Lyautey summarized their approach:

Diplomacy and political settlements took precedence over military operations.

Columns of troops gave way to a “creeping occupation,” in the tache d’huile (oil stain) method.

Military occupation encouraged economic development, which resulted in political stability.

Lyautey advocated these principles be implemented by a unified command, under the authority of one professional soldier.Footnote 80 Thus, for all the apparent reforms to the French conduct of colonial warfare, decision-making concentrated in an autocrat, who was free to combine harsh and conciliatory tactics as he saw fit, much as predecessors had done in previous campaigns. French officers assumed offensive operations to be necessary at the outset of pacification, to clear out armed resistance before less violent and more productive phases could follow.Footnote 81 The second wave of French colonial operations expanded the claims of empire from North Africa to West Africa, Madagascar, and Southeast Asia.

The British, not to be outdone by their continental rivals, intensified their own efforts in Africa. By the eve of the First World War, London had directed offensives throughout the eastern part of the continent, north from its Cape Colony and south from Egypt. Britons drew newfound confidence from technological tools with applications to warfare, with the “machine gun” as the most iconic and aptly named among a host of industrial inventions: indirect-fire artillery, poison gas, and airplanes.Footnote 82 These innovations made strong European powers stronger still in terms of military power projection, just as they sought to adopt softer, more benevolent rhetoric.

3.7 The Dutch in Indonesia

The Dutch, like the Russians and French, listed prestige of state and pride of culture as reasons to justify a growing colonial realm. Unlike those other European empires, concerned to keep up with British rivals, the Dutch relied on the British navy for protection. The Netherlands had deep historical connections to Java, the most populous of the Indonesian islands, through the spice-trading activity of its East India Company. The official government policy was not to occupy new territories from the Javan base, but to encourage company officials to sign contracts with surrounding indigenous sultanates. In 1841, the minister of colonies even ordered a retreat from new posts in Sumatra.

Government policy changed after the massacres at Lombok in 1894 and subsequent Dutch military campaigns in Aceh, 1896–1898. Afterward, the Dutch began direct political expansion into the “outer regions.” As with the Russians in Central Asia, there was no “conspiracy” from Europe to annex the entire archipelago. Instead, local agents tended to make requests to the colonial Indies government, rather than wait for instructions from the Netherlands. The process developed into a feedback loop, according to historian Elsbeth Locher-Scholten, in which “Dutch demands and pressure” for more political and economic control resulted in “growing Indonesian opposition,” which officials addressed with more demands for military campaigns. The leader of those efforts was General J.B. Van Heutsz, who developed what he called the Aceh strategy: “use of a mobile military police force, trained in guerrilla warfare, and the temporary concentration of military and civil authority.” The formula was similar to the one developed by French theorists Lyautey and Gallieni.

Dutch government authorities conceived of their expansion throughout the Indonesian archipelago as an “Ethical Policy” as of 1901. The high-mindedness from Europe did not prevent atrocities by military forces. Instead, the policy forced colonial officials to find pretexts of local grievance with indigenous leaders before they could intervene on behalf of the population. This was easy to do given the sultans’ “excesses” of luxury from the perspectives of “Calvinist mentality” Dutch agents. The shift from indirect trade partnership to direct political control was more the result of bureaucracy than it was a question of morality or even economics. The systematic control that some administrators had sought since the first half of the century became feasible once technical logistical problems decreased. The pathway to more formal empire opened with the founding of the national shipping company KPM in 1888. All that remained afterward was for local entrepreneurs to ask for the resources to expand their purviews. These demands became urgent after 1894, as the first Japanese war for control over the Korean Peninsula signaled a new entrant to the global imperialist competition.Footnote 83

3.8 The United States and the Philippines

When crisis in Cuba lent an excuse to declare war, American imperialists took advantage of an overextended Spanish empire. The humanitarian rationale, to assist rebels against cruel Spanish colonizers, provided cover for American agents’ desires for tropical resources, markets of consumers, and overseas ports for the growing naval power. Mere hours after the sinking of the USS Maine in Havana harbor in February 1898, the U.S. Navy destroyed the Spanish fleet that defended the capital of the Philippines in Manila. While the conventional war with Spain lasted only until August and cost the lives of 379 American soldiers and sailors, the counterinsurgency against Filipino revolutionaries dragged on across four years, during which 4,000 American servicemen died, along with 16,000 Filipino fighters and hundreds of thousands more noncombatants.

When the U.S. government resolved to keep the Philippines and its seven million inhabitants, President William McKinley claimed that he acted “to educate the Filipinos, and uplift and Christianize them.”Footnote 84 Such lofty idealism belied the terror and torture that Americans used to conquer their new colony. In many ways, military operations continued much as they had over the previous generation in the American West. In the fall of 1899, one general officer opined: “Filipinos are in identically the same position as the Indians of our country have been for many years, and must be subdued in much the same way, by such convincing conquest as shall make them realize fully the futility of armed resistance, and then win them by fair and just treatment.”Footnote 85 Most senior army leaders had experience fighting Native Americans, and they applied this Indian Country template of overwhelming violence at the outset of the campaign, followed by the establishment of a police state, abetted by indigenous allies.