The prevalence of overweight and obesity among Malaysian adolescents has increased dramatically between 1986 and 2016 from 4 to 23 and 30% in girls and boys, respectively(1). The rise in the incidence of excess weight is a function of many factors consisting of raised access to foods high in fats, added sugars and energies(Reference Vos, Kimmons and Gillespie2,Reference Te Morenga, Mallard and Mann3) , increased eating outside the home(Reference Poti and Popkin4), larger portion sizes(Reference Ello-Martin, Ledikwe and Rolls5) and a sedentary lifestyle(Reference Dehghan, Akhtar-Danesh and Merchant6,Reference Ghobadi, Hassanzadeh-Rostami and Salehi-Marzijarani7) . Studies in Malaysia have suggested that adolescents tend to binge on energy-dense snacks and drinks(Reference Boon, Sedek and Kasim8) and follow a low-fibre, high-fat diet(Reference Zalilah, Khor and Mirnalini9). In addition, a recent study in Malaysia has shown that those schoolchildren who ate breakfast had a lower total LDL-cholesterol and BMI compared with those who ate breakfast irregularly(Reference Mustafa, Abd Majid and Toumpakari10).

Fewer than 2 % of Malaysian adolescents (mean age 12·9 years) achieve the recommended levels of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (PA)(Reference Su, Sim and Nahar11), and they spend on average 4·7 h/d on media-based recreation activities, such as television viewing and electronic games(Reference Cheah, Chang and Rosalia12). Data from the Malaysian School-Based Nutrition Survey 2012 and Nutrition Survey of Malaysian Children (SEANUTS Malaysia) showed that more than 50 % of children and adolescents were considered as having low levels of PA(Reference Baharudin, Zainuddin and Manickam13,Reference Lee, Wong and Nik Shanita14) and high levels of sedentary behaviour(Reference Lee, Wong and Nik Shanita14). PA in Malaysian adolescents is, therefore, important(Reference Reilly and Kelly15).

The WHO regarded schools as a critical setting for enhancing public health nutrition and reducing the risk of unhealthy weight gain in childhood(16). To date, school-based interventions outside of Malaysia have been found to improve PA. However, the impacts have been small, short-term and have mostly varied between interventions(Reference Hynynen, Van Stralen and Sniehotta17–Reference Metcalf, Henley and Wilkin19). Promising policies related to the school food environment have included the provision of fresh fruits and vegetables(Reference De Sa and Lock20), as well as restricting the sales of sugar-sweetened beverages in the school setting(Reference Micha, Karageorgou and Bakogianni21). However, the effects of these programmes and their long-term sustainability are uncertain. Furthermore, despite school nutrition policies and guidelines, international research suggests that most schools fail to implement them(Reference Downs, Farmer and Quintanilha22,Reference Gabriel, de Vasconcelos and de Andrade23) .

The school food environment might be a useful means of improving dietary habits and promoting more active lifestyles in Malaysian adolescents, as, for example, two main meals (breakfast and lunch) are consumed by adolescents in this setting(Reference Moy, Ying and Kassim24). Generally, schoolchildren in Malaysia purchase food from the canteen and koperasi (school convenience shop). The koperasi sells school stationery, snacks and beverages, some of which are energy-dense. The staple foods sold at the canteen are fried rice and noodles, fried chicken and nuggets, energy-dense traditional cake and sugar-sweetened beverages. A study in Malaysia highlighted that the limited variety of food and vegetables served in school canteens may lead to deficient intakes of vitamins and minerals among adolescents(Reference Rosmawati, Manan and Izani25). Besides, access to junk food sold near schools may encourage unhealthy food practices(Reference Hayati Adilin, Holdsworth and McCullough26), such as snacking between meals and skipping main meals(Reference Rezali, Chin and Yusof27).

In Malaysia, there is a healthy food options guide for food and drink sales in school canteens and the school complex, which lists the approved or banned foods and beverages for the school canteen(28). This guideline is mandatory, but many school food canteens fail to adhere to it(Reference Ishak, Chin and Taib29).

Two Malaysian ministries are responsible for regulating school food quality (the Ministries of Education (MoE) and Health (MoH)). They use three broad mechanisms, including (1) setting food quality standards for school canteens, (2) providing food preparation training programmes for canteen operators and (3) monitoring canteen food quality. The deputy headmaster of a school should monitor quality standards, and a nutritionist from the MoH performs spot checks randomly throughout the year. However, canteen operators are rarely penalised for serving non-nutritious food; rather, the action is taken only in clear cases of food poisoning(28).

Internationally, governments have implemented school-based nutrition policies to restrict the sale of unhealthy foods(Reference Reilly, Nathan and Wiggers30,Reference Nathan, Yoong and Sutherland31) . Nevertheless, it also has challenges like conflicts with time for other school activities, different interests of the stakeholders (food canteen operators) (e.g. financial profit v. healthiness), or that the materials would not be applied as proposed(Reference Evenhuis, Vyth and Veldhuis32). Incorporating the contribution of stakeholders throughout the development phase in combination with evidence-based knowledge, frameworks and behaviour change approaches could improve interventions to address the identified challenges(Reference Van Nassau, Singh and van Mechelen33).

In Malaysia, the MoE subsidised food (breakfast) programmes are limited to students with low-socio-economic backgrounds at primary schools. However, extending this subsidy to secondary schools may provide more opportunities to eat more healthily, particularly for adolescents from low socio-economic backgrounds(Reference Mohammadi, Jalaludin and Su34).

Physical education (PE) in Malaysia is a compulsory subject taught in all primary and secondary schools. PE has the same status as other subjects in the school curriculum and is recognised as on par with other core subjects, although it is not a formally assessed subject. Tests for all physical fitness components are carried out on every student, and the results will be recorded. PE teachers in Malaysian schools comprise both PE majors and non-majors(Reference Wee35). PE is allocated two 40-min periods for a week in secondary schools(Reference Wee35). A survey among Malaysian adolescents showed that some students complained about the quality of PE classes. They also stated that PE lessons were often replaced with other lessons; the majority of PE teachers are not qualified, and PE class has been side-lined by a majority of the schools(Reference Wee35).

A framework for the development and evaluation of complex interventions was established by the UK Medical Research Council(Reference Craig, Dieppe and Macintyre36). A key stage in the development of such interventions is conducting formative research to identify the needs of the target population.

The term ‘stakeholders’ refers to certain groups and individuals who have a legitimate interest, or a ‘stake’, in the continuing effectiveness and success of an institution(Reference Mokoena37). In the school context, important stakeholders are parents, teachers, principals and canteen managers(Reference Uyeda, Bogart and Hawes-Dawson38,Reference Moore, Murphy and Tapper39) . Stakeholders can express their experience, expected barriers or facilitators regarding the implementation of school canteen guidelines and improving the quality of PA at school(Reference Wolfenden, Nathan and Sutherland40). Meanwhile, numerous studies internationally have used multiple stakeholders to explore school food environments and PA among adolescents(Reference Middleton, Keegan and Henderson41–Reference Asada, Hughes and Read45). However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies in Malaysia have explored concepts of healthy eating alongside PA, or discuss the barriers and facilitators for behaviour change in adolescents based on the multi-stakeholders’ perceptions.

The present study was a needs assessment as a part of the MyHeART BEaT project(Reference Mohammadi, Jalaludin and Su34,Reference Mohammadi, Jalaludin and Su46) to guide the development of the content and structure of future intervention. Current research focuses on the application of qualitative methods to inform the development of a school-based intervention to promote healthier eating and PA among adolescents in Malaysia. We involved a variety of stakeholders in secondary schools (adolescents, principals, PE teachers and food canteen operators) to explore: (a) stakeholders’ perceptions of the provision of healthy food and PA in the school setting and (b) stakeholders’ preferences and suggestions for school-based interventions to promote healthier eating and PA in Malaysia. Our findings may be relevant to other low- and middle-income settings.

Methods

Overview of the study setting

Malaysia’s multilingual public school system provides free education for all Malaysians in addition to the availability of private schools and home-schooling. Education is not free in international and private schools. Secondary education lasts for 5 years, referred to as Form 1 (secondary one; grade 7; 12–13 years old) to 5 (16–17 years old; Secondary 5; grade 11). There are 5·5 million adolescents aged 10–19 years, which equates to approximately 19 % of the total population; school enrolment in secondary education (% net) in Malaysia was reported at 72·2 % in 2018(47).

Study design and participants

Semi-structured focus groups were conducted in February 2018 with Form 2 students aged 13–14 years, attending four secondary schools in Perak and Selangor states (two urban and two rural schools) in Malaysia. Convenience sampling was used to recruit adolescents. Teachers were asked to invite all Form 2 students to participate by distributing a participant information sheet and consent form to the parents of the students. During the same period, in-depth interviews, guided by structured question guides, were also conducted with multiple stakeholders (one PE teacher, one school principal and one canteen operator) at each of the four schools. All participants (and/or the adolescents’ parent or legal guardians) asked to provide written informed consent before data collection commenced.

The questions were semi-structured focus groups and interview topic guides (different guides and questions) adapted from those used in previous studies but modified and developed to suit the context of the study(Reference Payán, Sloane and Illum48,Reference Lewis49) . Guides were pilot-tested among students and stakeholders for face validity to confirm the feasibility for data collection. The questions explored stakeholders’ perceptions of healthy eating and PA in the school setting; barriers for PA and consuming healthy foods in the school canteen; and expectations of an acceptable school-based intervention.

Data collection

Focus group discussions

A total of eight focus groups (lasting on average 40 min, range 35–45 min) were conducted by two facilitators (S.M. and H.A.M.), who were experienced and trained to conduct qualitative research (one researcher moderated the focus groups, and the other took detailed notes). Eight to ten adolescents participated in each focus group, which were conducted separately for girls and boys. Homogenous focus groups can create an atmosphere where students feel comfortable and free to speak, without having to defend their opinions. For example, females might not be able to express themselves freely in the presence of male participants. As all schools were Malay-based, focus groups were not arranged according to ethnicity (Malay, Chinese and Indian).

In-depth interviews

Twelve face-to-face in-depth interviews were conducted in four secondary schools with the headmasters, teachers and canteen operators by a trained enumerator. Open-ended questions were asked. Interviews lasted approximately 30 min (range 25–35 min).

The focus groups and interviews were conducted in Malay, digitally recorded, transcribed verbatim and anonymised. For both focus groups and interviews, the arrangement and wording of the questions were revised, if necessary, to explore emerging themes. Towards the end of the focus groups and interviews, the facilitator summarised the notes taken to participants to confirm their accuracy.

Data analysis

Data analysis was carried out in Malay, and translation of the data into English was limited to selected quotes. Analysing data in the original language prevents potential misinterpretations of participants’ statements(Reference Birbili50–Reference Lincoln, González y González and Aroztegui Massera54). Two independent data analysts (F.A.B. and S.R.R.) listened to the recordings to check precision with the transcriptions. Transcripts were also compared with the facilitator’s detailed notes to ascertain their credibility. The analysis of transcripts was conducted by two trained researchers (F.A.B. and S.R.R.) and subsequently verified by H.A.M./M.D./T.T.S./M.Y.J. Selected themes and quotes were translated into English by F.A.B. and S.R.R., who are native Malay speakers, and back-translated to Malay by an independent bilingual researcher (H.A.M.). Data collection and analysis were in parallel, so that data collection was completed when saturation was reached (i.e. data had a range of perceptions and variation of replies of participants, and no new themes arose from the analysis). Data organisation and coding were facilitated by NVivo software version 10 (QRS International Pty Ltd, UK).

Data were analysed thematically(Reference Burnard55), following an inductive approach by using a framework method, which included five stages(Reference Gale, Heath and Cameron56). First, familiarisation with the data was conceded by reading transcripts repeatedly. Second, two trained researchers (F.A.B. and S.R.R., who are both Malay, English speakers) separately open-coded three randomly selected transcripts to start categorising data, so they could be compared with the rest of the data set. Third, coding inconsistencies (e.g. dissimilarities in terms used by the coders and whether codes were suitable to respond to the research questions) were discussed until a set of codes that made an initial framework was agreed. Based on this, the remaining transcripts were independently coded to establish any new themes and codes. Then, the coders discussed again to refine the initial framework, detect new codes and themes.

Inter-coder reliability was 95 %, as calculated by dividing the number of agreements by the sum of agreement and disagreements. Fourth, indexing (systematically applying the framework to all transcripts) was applied by one researcher using the qualitative data analysis software NVivo version 10 (QRS International Pty Ltd, UK), which simplified the comparison of similarities and differences within and between the focus groups/interviews, and the evaluation of patterns in the views of participants, according to each theme. Finally, charting data into the framework matrix was carried out by reordering the data in a chart. Themes were organised and reorganised into themes and sub-themes as described for thematic analysis(Reference Burnard55). Themes and sub-themes are supported in this report by representative quotations from participants (indicated by gender, rural/urban and stakeholder). These were selected to best reflect the variety of answers.

Results

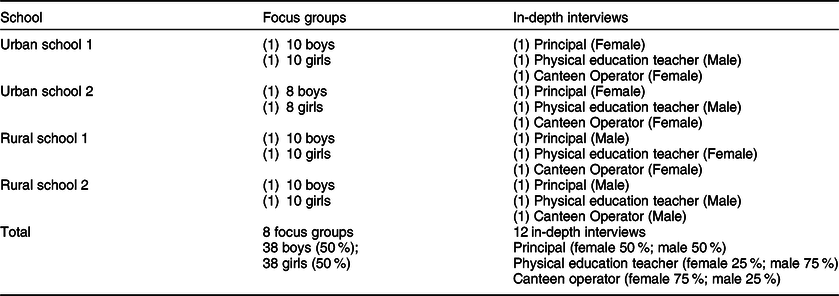

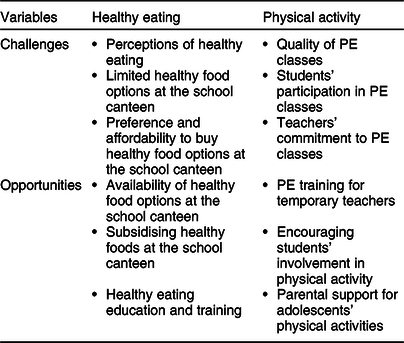

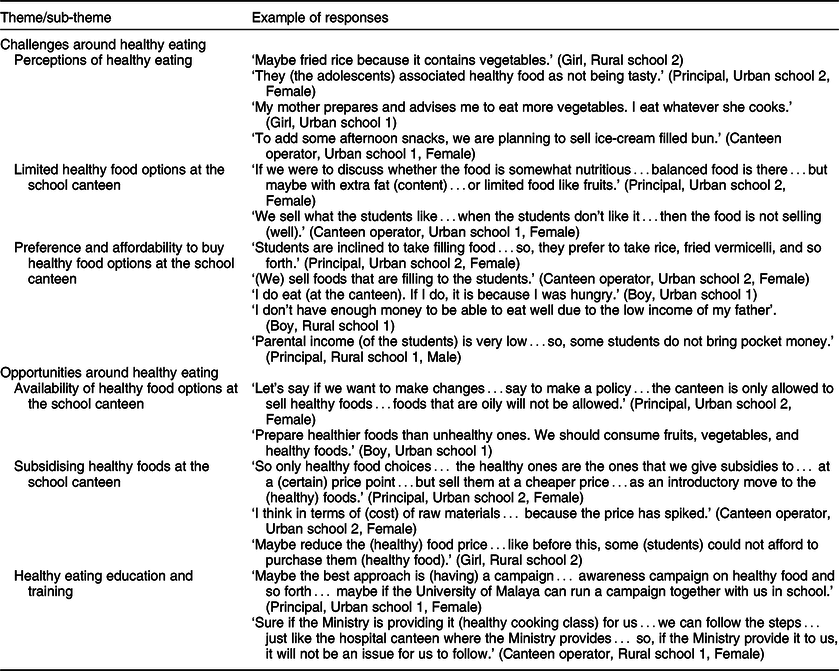

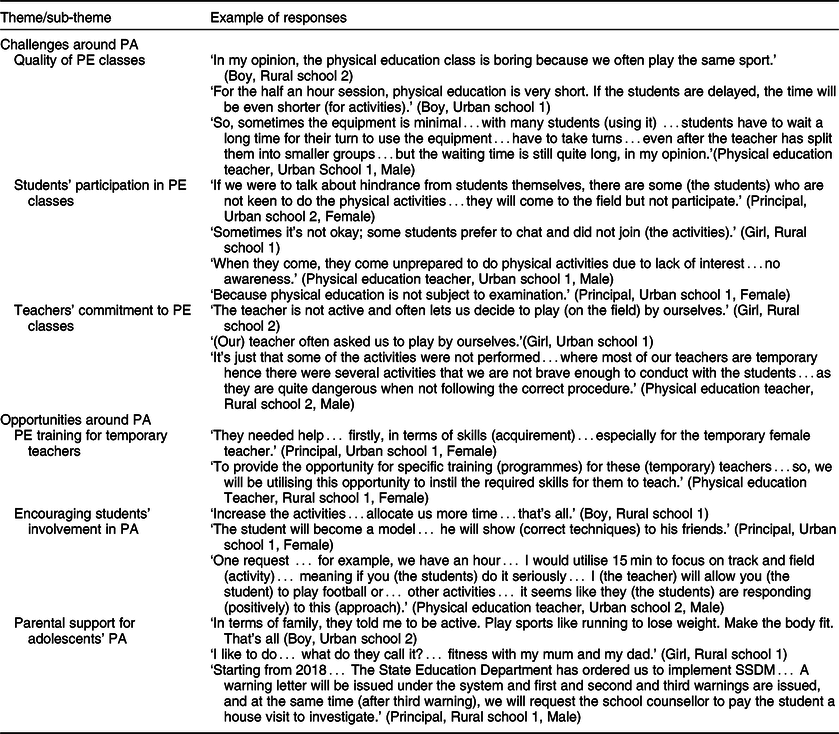

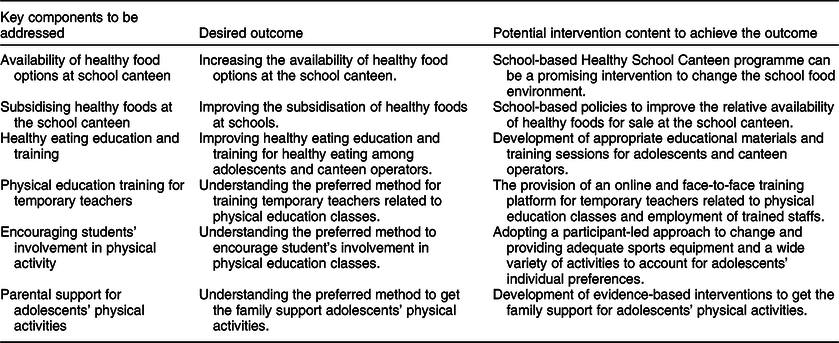

The focus groups and in-depth interviews were conducted with seventy-six adolescents (thirty-eight boys; thirty-eight girls) and multiple stakeholders (n = 12) from four schools, respectively. Stakeholders were principal (two female; two male), PE teacher (one female; three male) and canteen operator (three female; one male). Table 1 shows the characteristics of participants of focus groups and in-depth interviews in two urban and two rural schools. We identified several themes around the challenges faced by adolescents and stakeholders and suggestions that would need to be considered when designing future interventions to promote healthier eating and PA in secondary schools in Malaysia (Table 2). Examples of responses related to healthy eating and PA based on these themes are shown in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. In addition, the Malay version of responses is available in Supplementary material 1. The summary of the findings and their implications for the development of an intervention to promote healthier eating and PA among Malaysian adolescents is described in Table 5.

Table 1 Participation of focus groups and in-depth interviews in two urban and two rural schools

Table 2 Challenges and opportunities for healthy eating and physical activity

PE, physical education.

Table 3 Challenges and opportunities around healthy eating arising in the eight focus groups discussions among adolescents (n 76) aged 13–14 years and twelve in-depth interviews (headmasters, physical education (PE) teachers and food canteen operators) from four secondary schools in Perak and Selangor states of Malaysia

Table 4 Challenges and opportunities around physical activity (PA) in the eight focus groups discussions among adolescents (n 76) aged 13–14 years and twelve in-depth interviews (headmasters, physical education (PE) teachers and food canteen operators) from four secondary schools in Perak and Selangor states of Malaysia

Table 5 Implications of findings for the development of an intervention to promote healthier eating and physical activity among adolescents in secondary schools in Malaysia

Challenges around healthy eating

Perceptions of healthy eating

Adolescents seemed to have common misconceptions of healthy eating, and most perceived fried food as being healthy. One adolescent perceived that fried rice served in the school canteen was healthy because it contains small amounts of vegetables. According to the interviews with the principals, students tended to associate healthy food with foods that are not tasty.

Some adolescents mentioned that their families’ guidance helped them to change their understanding of healthy food; some stated that their mothers prepare and provide advice on food selection. Overall, adolescents thought that healthy foods were being served by the school canteen, with fried chicken, fried rice and coconut milk rice being considered healthy foods.

Canteen operators perceived that healthy eating would not be feasible since healthy food is unpopular among adolescents and, therefore, selling healthy foods would not be a profitable practice. When asked about their comprehension of healthy food options, operators seemed to misunderstand what healthy options might be, with one giving an example that an ice cream-filled bun would be a healthy snack for adolescents.

Limited healthy food options at the school canteen

Adolescents generally agreed with each other that canteen vendors offer them limited options of food. Deep-fried and oily foods, like fried chicken and fried rice, were common options bought from the canteen. They also perceived that the school canteen provided insufficient amounts of healthy options, like fruits and vegetables, especially in rural schools.

Principals acknowledged the limited variety of foods in canteens and explained that food items are usually sold with profits and the cost of the raw materials in mind. One principal explained that the foods available could still form part of a balanced diet despite healthy options, such as fruit, is limited and other foods having a high in fat content.

Canteen operators explained that they are following the Healthy Canteen Guidelines provided by the Ministry of Health in Malaysia. They thought the limited healthy options offered in school canteens were the result of a ‘supply and demand factor’ by the students, whereby adolescents prefer quick and simple food options and have a low interest towards healthy foods. Operators perceived that selling healthier foods would result in fewer purchases, which in turn would cause food waste and a financial loss to the canteen.

Preference and affordability to buy healthy food options at the school canteen

Principals perceived that adolescents preferred buying unhealthy options in the canteen, as they are more filling (energy-dense such as junk foods) than healthier foods. Canteen operators also seemed to agree with this notion, in that adolescents preferred to buy filling foods (energy-dense such as junk foods), even if they were unhealthy.

Adolescents also reported preferring to buy their meals in the canteen because the menu has filling foods, thus preventing hunger during the school period. Adolescents from the rural area also stated a lack of money to buy food, mainly when asked about obstacles to healthy eating.

Principals from rural schools mentioned that adolescents at their schools came from low socio-economic backgrounds and it was common that they come to school without, or with minimal, pocket money, thus limiting their ability to buy foods in the first place. Canteen operators corroborated this. Particular to this issue, we found that students within urban schools prefer unhealthy and filling foods (to fight hunger without caring about the nutritional value) and affordability was not the primary concern.

Opportunities around healthy eating

Availability of healthy food options at the school canteen

Principals expressed the view that only healthy foods should be made available at the school canteen and the sale of unhealthy foods should be prohibited to enhance healthy eating behaviours among adolescents.

Most adolescents thought that canteen operators increasing the availability of healthy food options would facilitate them choosing healthy foods. One adolescent even suggested that foods available should form parts of a balanced diet, such as fruits and vegetable dishes. However, canteen operators explained that healthy food options were limited because some equipment for healthy cooking (e.g. utensils for roasting or steaming) are not available and often expensive for them to acquire and use when preparing meals.

Subsidising healthy foods at the school canteen

Subsidising raw ingredients and providing food coupons were some of the approaches suggested by the stakeholders to promote healthier eating. Both principals and canteen operators agreed that healthy eating could be made possible if food subsidies were provided to the schools. Adolescents also reported that providing subsidies to reduce the burden of cost to canteen operators would allow healthy foods to be sold at lower prices. They emphasised the need for canteens to have healthy food options at lower prices, which would increase the likelihood of them opting for healthy foods.

Healthy eating education and training

All principals suggested that health education programmes should run throughout the year to change attitudes towards healthy food among adolescents. Some suggestions involved campaigns and festivals providing free healthy foods in order to encourage students to try them.

Adolescents, however, gave mixed responses when asked about the potential for health education to promote healthier eating in schools. Some adolescents were against this suggestion, explaining that educational materials, such as brochures, would not help to enhance literacy around healthy eating. However, some adolescents thought that health education might be useful, as it might help students learn to distinguish healthy from unhealthy food options.

Canteen operators seemed to like the idea of offering them the opportunity to enrol in healthy cooking classes. They would also favour receiving guidance, for example, alternatives to unhealthy foods and healthy recipes, as well as making healthy cooking tools available to aid them in preparing healthy food for students.

Challenges around physical activity

Quality of physical education classes

Adolescents often thought that the PE classes offered at school were short and boring, offering a limited variety of activities. Insufficient sports equipment and teaching materials were commonly perceived among PE teachers as challenges around PA in schools. The quality of PE classes was an issue mentioned by adolescents; they perceived that the low teacher–student ratio hampered the efficiency of the sessions. This was particularly the case for rural schools, which have limited equipment reducing opportunities for students to participate in more activities.

Students’ participation in physical education classes

In both rural and urban schools, principals, PE teachers and adolescents thought that PE classes had low participation from students. Some adolescents, in particular, reported that despite attending the classes, they preferred not to participate in the activities. PE teachers perceived that participation in classes depended on adolescents’ interests and personal preferences, whereas principals thought that low participation might be because PE classes were not assessed formally.

Teachers’ commitment to physical education classes

Adolescents reported that one of the challenges they faced during PE classes was that teachers were not fully committed to the class. They mentioned that teachers were not active and often instructed students to do their activity. This was highlighted in both urban and rural schools.

Principals explained that PE teachers’ low commitment towards their classes was mainly due to limited skills, as many did not have a PE background and were employed as temporary staff. One of the teachers explained that they were often unable to follow the activity procedures to avoid injury to students, especially with regard to technical activities.

Opportunities around physical activity

Physical education training for temporary teachers

Principals and PE teachers felt that more training should be provided to the teachers to conduct PE classes appropriately. As the number of PE teachers is limited, both of these stakeholders largely agreed that training would aid teachers’ skills and methods for delivering the classes.

Encouraging students’ involvement in physical activity

In order to encourage student participation in PA, most adolescents suggested that schools should consider increasing both the frequency and duration of PE classes so that they have many opportunities to be more physically active. Students also felt that peer encouragement would help them to get involved and become more physically active. One of the principals also suggested that friends acting as a role model for specific activities would increase adolescents’ involvement in classes. For example, an adolescent who plays football could help teach their friends the proper techniques to play the sport.

In addition, PE teachers suggested the implementation of a reward system for adolescents, especially those who are highly likely to not participate in PE classes. The reward system may function by engaging students to join the planned class, before giving them their reward of doing their preferred activity. Furthermore, both principals and PE teachers suggested that sports competitions could be an outlet to help increase adolescents’ interest to get involved in physical activities.

Parental support for adolescents’ physical activities

Students from both rural and urban schools mentioned that they tend to be more physically active when they receive support from their parents. Examples of parental support provided by the students to facilitate this included parents dropping them off at sports facilities and joining them when engaging in PA.

Principals also addressed the importance of active parental support to promote adolescents’ PA and mentioned that schools had implemented a system, called SSDM (Sistem Sahsiah Diri Murid) or Students’ Self-Affair System, whereby a warning letter is issued to students who missed a PE class. After three absences, the school counsellor contacts the parents to discuss appropriate actions.

Discussion

In our qualitative study, Malaysian adolescents, school principals, PE teachers and canteen operators highlighted several challenges with regard to healthy eating and PA in secondary schools. Participants provided important insights on how the school environment could facilitate healthier eating and PA, including subsidising and increasing the availability of healthy foods; providing nutrition and PA training for adolescents and stakeholders; and encouraging adolescents to participate in PA via peer and parental support. These insights are essential to inform interventions to promote healthy eating and PA in secondary schools in Malaysia.

The main barriers for healthy eating at school identified by adolescents in the current sample included the lack of healthy food options, the availability of unhealthy foods and issues around preferences and affordability. In addition, there seemed to be several misconceptions regarding what constitutes healthy eating, which might have contributed to adolescents’ consumption of more unhealthy foods. Our finding is in contrast to a study of Irish adolescents, who had a good understanding of what healthy eating involves(Reference Fitzgerald, Heary and Nixon57). Both adolescents in the current and earlier qualitative studies(Reference Fitzgerald, Heary and Nixon57,Reference Stevenson, Doherty and Barnett58) perceived that food preferences and foods sensory qualities (i.e. texture, appearance and smell) play a more central role in their food choices. This is corroborated by a study of forty adolescents in Swiss schools, who perceived that enhancing the attractiveness of healthy choices would be the most effective approach to improving eating habits(Reference Della Torre Swiss, Akré and Suris59).

Families, especially mothers, were described as influencing the food habits and perceptions of healthy food of Malaysian adolescents. This was also highlighted in studies among adolescents(Reference Fulkerson, Larson and Horning60,Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Larson and Fulkerson61) . Since mothers were typically regarded as being responsible for preparing family meals(Reference Rathi, Riddell and Worsley62,Reference Berge, MacLehose and Larson63) , good maternal knowledge of nutrition could improve the quality of food intake and eating behaviour of adolescents at home(Reference van Ansem, Schrijvers and Rodenburg64).

Other barriers to healthy eating in secondary schools that have been reported in earlier research included poor school meal provision, ease of access and the relatively low cost of fast food(Reference Shepherd, Harden and Rees65). In contrast, healthy eating has been suggested to be facilitated by parental support, broader accessibility of healthy foods, desire to look after one’s appearance and will-power(Reference Shepherd, Harden and Rees65). Some of these findings agree with the current study’s results, where adolescents suggested that increasing the availability and reducing the cost of healthy foods would help them make healthier choices in the school canteen.

School food environments are different between rural and urban areas(Reference Hoffman, Srinivasan and Levin66). Identified challenges in rural schools include limited administrative capacity, difficulty in hiring and retaining qualified staffs, physical infrastructure limitations, as well as limited food supply and purchasing options(Reference Hoffman, Srinivasan and Levin66,Reference Yettik, Baker and Wickersham67) . Food habits among rural adolescents are characterised by traditional food, and a lower frequency of milk products, meat/fish/eggs, vegetables and cereals. In contrast, adolescents in urban areas eat more junk food, have a higher amount of pocket money and are engaged in less manual activities and walking than adolescents in rural areas(Reference NzefaDapi, Nouedoui and Janlert68).

Interestingly, perceptions of stakeholders in the current study did not often differ in urban or rural areas. One exception was that cost or affordability of foods offered in the school canteen, which might be a more important factor preventing healthier choices for adolescents based in rural, compared with urban, areas. Lack of money to purchase healthy food was also a barrier to healthy eating for adolescents in earlier qualitative studies(Reference Melo, de Moura and Aires69–Reference Power, Bindler and Goetz71). Our findings suggest that inequalities in the foods consumed at urban and rural schools could potentially be overcome by using subsidies for healthy foods. In addition, some studies have shown that it is possible to improve food availability and increase sales of healthy items in secondary school canteens(Reference French, Story and Fulkerson72,Reference Hannan, French and Story73) .

All stakeholders involved in the current study perceived that the main barriers for adolescents being physically active at school were the low quality of PE classes; adolescents’ low level of participation in classes; and PE teachers’ limited skills and commitment. Lack of time to engage in PA during the PE class was another perceived challenge by adolescents, which is a barrier commonly observed elsewhere(Reference Van Royen, Verstraeten and Andrade74–Reference Martins, Marques and Sarmento76). However, in these earlier reports, adolescents linked the lack of time to engage in PA due to school demands (e.g. overloaded curriculum, assignments, private lessons and prioritising academic success).

In addition, obstacles related to infrastructure and available equipment were considered as barriers to promoting high-quality PA in schools by all stakeholders, which has been reported by earlier studies as well(Reference Nathan, Elton and Babic77,Reference Morton, Atkin and Corder78) . However, a Malaysian adolescent cohort study (MyHeARTs) highlighted that activities associated with higher fitness in adolescents typically took place outside of school, in the evening or at weekends(Reference Toumpakari, Jago and Howe79), which suggests that PE may be less important than out-of-school physical activities for adolescent health.

All stakeholders highlighted that some adolescents do not engage during PE classes, potentially due to personal interests or preferences. Enjoyment of participation in PE classes is an important facilitator of adolescent PA(Reference Morton, Atkin and Corder78), and offering a wider variety of activities during classes might help contribute to more active participation at school. In addition, to actively engage adolescents in PE classes, PE teachers must be trained appropriately through Initial Teacher Training. When providing PE, a teacher should carefully consider how they will adapt demonstrations and explanations of the skills being taught to meet the needs of the students in their class and the intended content(Reference Makopoulou and Armour80). Monitoring systems need to be proven effective to ensure that PE programmes in Malaysian schools are implemented properly. PE classes are not implemented uniformly across schools and largely depend on the discretion of the school head and management. This falls short of achieving the level that is required to realise the targeted health and well-being benefits. Moreover, an effective PE system requires the collaboration of its multiple stakeholders.

Finally, all stakeholders in the current study perceived social support and encouragement as important when promoting PA. Social support, particularly from friends, family and teachers, has been consistently linked to higher levels of adolescent PA in earlier research(Reference Laird, Fawkner and Kelly81,Reference Mendonca, Cheng and Melo82) .

A few school-based nutritional interventions have been implemented in Malaysia(Reference Gunasekaran, Sharif and Koon83–Reference Wafa, Talib and Hamzaid86). However, most interventions to date are focused on either the prevention of obesity or disordered eating, rather than general improvements to nutrition and PA in all students. To our knowledge, Malaysia does not have a comprehensive intervention programme that promotes the components of healthy eating and an active lifestyle among adolescents.

Two previous canteen-based food nutrition intervention studies in Malaysia successfully improved healthy food knowledge among food handlers(Reference Rosmawati, Manan and Izani25) and students’ perception of healthy food choices(Reference Nik Rosmawati, Wan Manan and Noor Izani87). However, there was no evidence of improvement in the primary schoolchildren’s preferences for fruits(Reference Nik Rosmawati, Wan Manan and Noor Izani87). The intervention between food handlers found that almost one-third of fast food and food not recommended for sale were available in the canteens because school canteens prioritised making profits(Reference Rosmawati, Manan and Izani25). Meanwhile, there is still some gaps in data and demand for appropriate nutrition intervention among adolescents.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to utilise the Medical Research Council framework for the development of complex interventions for schoolchildren in Malaysia(Reference Uyeda, Bogart and Hawes-Dawson38). We explored secondary school stakeholders’ perceptions to inform the design of a future intervention to improve dietary and PA behaviours in Malaysian adolescents. Use of the Medical Research Council framework is a strength of this study, as conducting this type of formative research before intervention development is likely to result in more feasible and acceptable interventions. A wide range of stakeholders was involved (adolescents, principals, teachers and canteen operators), who were recruited from both urban and rural areas of Malaysia, thus enabling a wide range of insights into the topics explored. Nevertheless, the generalisability of the findings to different geographical regions of Malaysia cannot be assumed and, despite thematic data saturation being reached, the sample size was relatively small. Malaysia comprises three main ethnic groups (Malay, Chinese and Indian), but we only included schools that were Malay-based and focus groups were not arranged according to ethnicity (Malay, Chinese and Indian). Students of other ethnicities could have different perceptions due to potential cultural differences. All ethnicities should participate in future studies to develop inclusive interventions. The results cannot be generalised to adolescents studying in a non-formal education programme. Furthermore, the students may have given socially desirable answers throughout the focus group discussions, mainly when they could not express their problems or if they overstated their positive perceptions.

Conclusions

The current study suggests that several challenges and opportunities to following a healthy diet and engaging in high-quality PA in Malaysian secondary schools should be addressed in a future intervention to promote these behaviours among Malaysian adolescents. Stakeholders thought that adolescents’ misperceptions, limited availability of healthy options, unhealthy food preferences and affordability were important challenges preventing healthy eating at school. Low-quality PE classes, limited adolescent participation and teachers’ commitment during lessons perceived as barriers to adolescents being active at school. They perceived that a future school-based intervention should ideally improve the availability and subsidies for healthy foods, provide engaging in health education/training for both adolescents and PE teachers, enhance active adolescent participation in PE classes, provide adequate sports equipment and variety of physical activities, develop role modelling, and social support mechanisms to facilitate engagement with PA. Rather than providing adolescents with only relevant knowledge related to a healthy lifestyle, they require training to deal with the obstacles. Such educational platforms should also deliver knowledge and guidance related to PA and healthy eating for their parents. Results from our study can form the basis for the development of a school-based intervention to promote healthier eating and encourage PA to Malaysian adolescents.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Shafina Radiah Mohamad Rafix (SRR) and Mohd Fadzrel bin Abu Bakar (FAB) for their valuable cooperation and support during data collection. Financial support: This study was undertaken as part of the MyHeARTBEaT (Malaysian Health and Adolescents Longitudinal Research Team Behavioural Epidemiology and Trial) project (IF017-2017) in Malaysia, funded by the Academy of Sciences Malaysia (Newton Ungku Omar Fund) and the UK Medical Research Council (grant number MR/P013821/1). The sponsors have had no input to the study design; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data and no input to the writing of the report; and the decision to submit the report for publication. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: H.A.M., A.P., T.T.S., S.M., M.D., Z.T., L.J. and R.J. contributed to the conception and design of the study. H.A.M. and L.J. led the project and secured the necessary funds. S.M., H.A.M., T.T.S., M.D., M.Y.J. and M.N.A. were responsible for data collection, transcription, coding and analysis. S.M., H.A.M., A.P. and T.T.S. contributed to drafting the manuscript and provided critical input. All authors have read, revised and approved the final draft of the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving study participants were approved by the University of Malaya Medical Centre Research Ethics Committee (MREC ID NO: 2 017 106–5656). All participants (and/or the adolescents’ parent or legal guardian) were asked to provide written informed consent before data collection commenced.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020002293.