1.1 Introduction

Huawei is now China’s most prominent multinational company. In 2018, Huawei achieved sales of USD 105.2 billion and operated in over 170 countries around the world, employing around 188,000 people. Forty-five percent of all employees are focused on R&D (Huawei, 2019), giving the firm strong technological capabilities. Huawei has now even surpassed Ericsson and Nokia to become the largest telecommunication infrastructure equipment company in the world. It is also the second largest maker of smart phones.

Not surprisingly, academics, business leaders, and policy makers have become very interested in understanding how Huawei has been able to rise from its humble beginnings in Shenzhen as an importer of analog telephone switches to a globally operating information technology manufacturing and service firm. Huawei is now frequently featured on the cover of international business magazines (Economist, 2012) or as a case study in Western business schools (Hitt, Ireland, and Hoskisson, Reference Hitt, Ireland and Hoskisson2008; Peng, Reference Peng2010) because it has accomplished something that is still rare for a Chinese company: turning itself into a world-leading company and R&D powerhouse.

To date, writing an academic-quality book on Huawei has almost been impossible given that it has been a secretive private company. Until 2010, Huawei did not even publish its governance structure, let alone any information that would make it possible to get deeper insights into how the company operates. Realizing that this secrecy was hurting Huawei’s ability to further expand in key international markets, the firm began to open itself up more. Ren Zhengfei, the founder and key leader, started to give interviews to Western journalists (Economist, 2014a; Pullar-Strecker, Reference Pullar-Strecker2013).

More importantly, the firm granted Tian Tao, a Chinese business journalist and long-time advisor to Huawei, along with Chunbo Wu, an academic from Renmin University of China, access to internal company documents. Huawei also gave them permission to interview hundreds of current and former Huawei managers. Based on their research, Tian and Wu published The Huawei Story (Reference Tian and Wu2015), first in Chinese and a few year later in English. The book provides the most comprehensive account of the development of Huawei since its founding in 1987. It lays out in detail the management philosophy and values that have guided the firm’s development as it struggled to overcome its weak financial and organizational capabilities and become an international leader in the information and communication technology industries (ICT). An expanded version of the book was published recently (Tian, De Cremer, and Wu, Reference Tian, De Cremer and Wu2017).

With the help of Tian Tao, Zhejiang University School of Management has set up the Ruihua Institute for Innovation Management to further academic research and teaching on how and why Huawei has been able to outcompete so many domestic and international rivals. Earlier explanations for the success of Huawei emphasize Chinese cost advantages, stronger customer centricity, a strategy of first entering peripheral markets before competing in core markets, and the gradual buildup of ever more sophisticated technological capabilities that made Huawei a leader in the next-generation technology of 5G mobile telephony (Fu, Reference Fu2015; Z.-X. Zhang and Zhong, Reference Zhang, Zhong, Lewin, Kenney and Murmann2016). As the research at the Ruihua Institute progressed, however, it became clear that at the center of Huawei’s success lies an organizational capability to continuously transform itself.

For this reason, we made the decision to write a book entirely focused on Huawei’s transformation since its beginning in 1987. We believe that scholars interested in organizational change or more specifically change in Chinese firms will benefit the most from learning about Huawei’s transformation capabilities. Because we realized that the development of new and the breaking of old routines is central to Huawei’s transformation, we decided to use as our overarching analytic lens the theory of routines-based organizational capabilities (Becker, Lazaric, Nelson, and Winter, Reference Becker, Lazaric, Nelson and Winter2005; Murmann, Reference Murmann2003; Nelson and Winter, Reference Nelson and Winter1982; Nigam, Huising, and Golden, Reference Nigam, Huising and Golden2016; Parmigiani and Howard-Grenville, Reference Parmigiani and Howard-Grenville2011; Szulanski and Jensen, Reference Szulanski and Jensen2008; Winter, Reference Winter2003).Footnote 1 We follow here in the tradition of Robert Burgelman, whose studies of Intel have helped advance our understanding the evolutionary processes underpinning corporate transformations (Burgelman, Reference Burgelman1991, Reference Burgelman2002; Burgelman and Grove, Reference Burgelman and Grove2007). To be sure, there is a large literature on organizational change, and our book is not novel in terms of focusing on organizational change. What makes Huawei interesting is its rate of growth and the level of detail in which we can observe not only the creating of routines but also the breaking of routines across most of the major functions of the firm. This makes Huawei an ideal case to advance the theory of routines and dynamic capabilities to change routines (Pisano, Reference Pisano2017; Teece, Reference Teece2007; Teece, Pisano, and Shuen, Reference Teece, Pisano and Shuen1997). Our book will be particularly appealing to academics in the field of strategy, management, and business history.

In December 2018, Huawei was in the headlines all over Western world when its chief financial officer was arrested in Canada on the request of the US government for allegedly violating US trade sanctions. This event is taking place against the larger backdrop of the US government stepping up its campaign to limit Chinese telecom participation in building 5G networks in Western countries because of national security considerations (Woo, Reference Woo2018). To avoid false expectations, we would like to be explicit at the outset that the geopolitical struggles over who builds, runs, and effectively controls national telecommunications infrastructures is a topic we will not be dealing with in this book. We are focused solely on the management transformation of Huawei. This transformation by itself is worthy of a scholarly investigation. In the conclusion chapter we offer, however, a short appraisal of Huawei’s future growth challenges, and in this context we will briefly detail the geopolitical challenges Huawei currently faces as it tries to commercialize its leading technological position in 5G mobile technology.

Our book should not be seen as an official history of Huawei or a mouthpiece for current and former executives. The research team has been entirely independent of Huawei. The views expressed in this book are ours alone. We benefited immensely, however, from our interviews with many former Huawei executives, access to the firm’s internal newspapers, and the presentations of many former executives at the quarterly Huawei forum of the Ruihua Institute for Innovation Management. In Appendix B, we list the names of the presenters and the title of the presentations at Ruihua Institute. In Appendix C we provide a list of the interviews we conducted, the persons interviewed, and the various positions they had held within Huawei. But we have also drawn extensively on external information, as will become evident in each of the chapters. All information sources are referenced throughout the book.

1.2 A Brief History of Huawei

Huawei was founded in 1987 by Ren Zhengfei in Shenzhen, where the Chinese government had set up the first special economic zone in May 1980 to experiment with private initiative and foreign investment in what was otherwise a centrally controlled and collectively owned economy (For a sympathetic biography of Ren, see Li, Reference Li2017). It is not a coincidence that the first special enterprise zone was set up right across the border from Hong Kong. Deng Xiaoping, the key political leader in China at the time, became eager to reform the Chinese economy partly because he noticed how much better capitalist Hong Kong had developed than communist mainland China in the previous three decades (Vogel, Reference Vogel2013).

The rise of Huawei parallels in large part the development of Shenzhen as a commercial hub in China. Shenzhen’s population increased from around 300,000 inhabitants in 1980 to over 15 million today, making it the most densely populated city in China (Shenzhen Standard, 2014). Ren Zhengfei, who previously had worked as a civil engineer in the Chinese military corps of engineers, started Huawei just as the Chinese government started a strong push to upgrade the telecommunications infrastructure across the country. In 1978, China had only 2 million telephone subscribers and a total capacity of 4 million lines (Tian and Wu, Reference Tian and Wu2015, p. xviii). In 2015, there were over 1.3 billion mobile phone users (Statista, 2016a). In one generation, having a telephone went from a luxury to what is perceived as a necessity of daily life. Visit any large Chinese city today and you will notice that all people have smart phones in their hands. To get the entire Chinese population connected with mobile phones, the investments that had to be made in telecommunications infrastructure were massive.

A key element of Huawei’s history is that it faced fierce competition from the beginning both from domestic and international players. In light of how successful Huawei has become, it is easy to fall into the trap of thinking that the firm’s success was foreordained and that the rise to the top was easy and smooth. When Huawei entered the Chinese market in 1987 as a mere importer of telephone switches, the technologically sophisticated Western firms – Ericsson, Alcatel, Siemens, AT&T (later called Lucent Technologies), Northern Telecom (later called Nortel), Fujitsu, and NEC from Japan – were all competing for orders in China (Tian and Wu, Reference Tian and Wu2015, p. xxiv). What is more, in the mid-1980s there were many Chinese entrepreneurs and managers of state-owned local companies who regarded the growth prospects of the telecommunications equipment market as attractive. According to Tian and Wu (Reference Tian and Wu2015, p. xxv) at least 400 firms entered the market in this period, creating strong competition also at the lower technological end of the market.

For anyone who has studied the development of industries in other countries, the magnitude of entries into Chinese markets that were opened to new entrants is typically by an order of magnitude larger than in other countries. Klepper (Reference Klepper2015) provides extensive data on US industries and Murmann (Reference Murmann, Caporael, Griesemer and Wimsatt2013) for other countries, demonstrating this fact. As part of their research on the textile color industry in China, Jiang and Murmann (Reference Jiang and Murmann2012), for example, encountered at least 800 Chinese start-ups in the 1980s and 1990s. Turning to a more contemporary example, in addition to the well-known Chinese smart phone brands Huawei, Lenovo, HTC, and Xiaomi, at least 445 other firms manufactured smart phones in China in 2015 (Ibisworld, 2015). No other country comes anywhere close to this large a number of firms competing in the same market. One reason for this is clearly that the Chinese population of 1.3 billion people is four times larger than that of the United States, which is the largest market among the Western countries.

Huawei faced strong competition from the beginning, and competition in the industry continued to be fierce over the next three decades even though the global telecommunications equipment market increased from 119 billion USD in 1993 (U.S. International Trade Commission, 1998) to 354 billion USD in 2011 (Statista, 2016b). Especially when the internet bubble burst in 2001, many ICT firms struggled with overcapacities. Since then, many of the key players have merged because they could no longer compete successfully as standalone companies. Between 2006 and 2016, the telephone equipment businesses of Nokia, Siemens, Alcatel, and Lucent successively merged in the hopes of being able to better compete with Huawei and now operate under the Nokia name (Nokia, 2016). By 2013, Huawei became the largest telephone network equipment supplier in the world and over the years moved from simply making equipment to offering turnkey solutions.

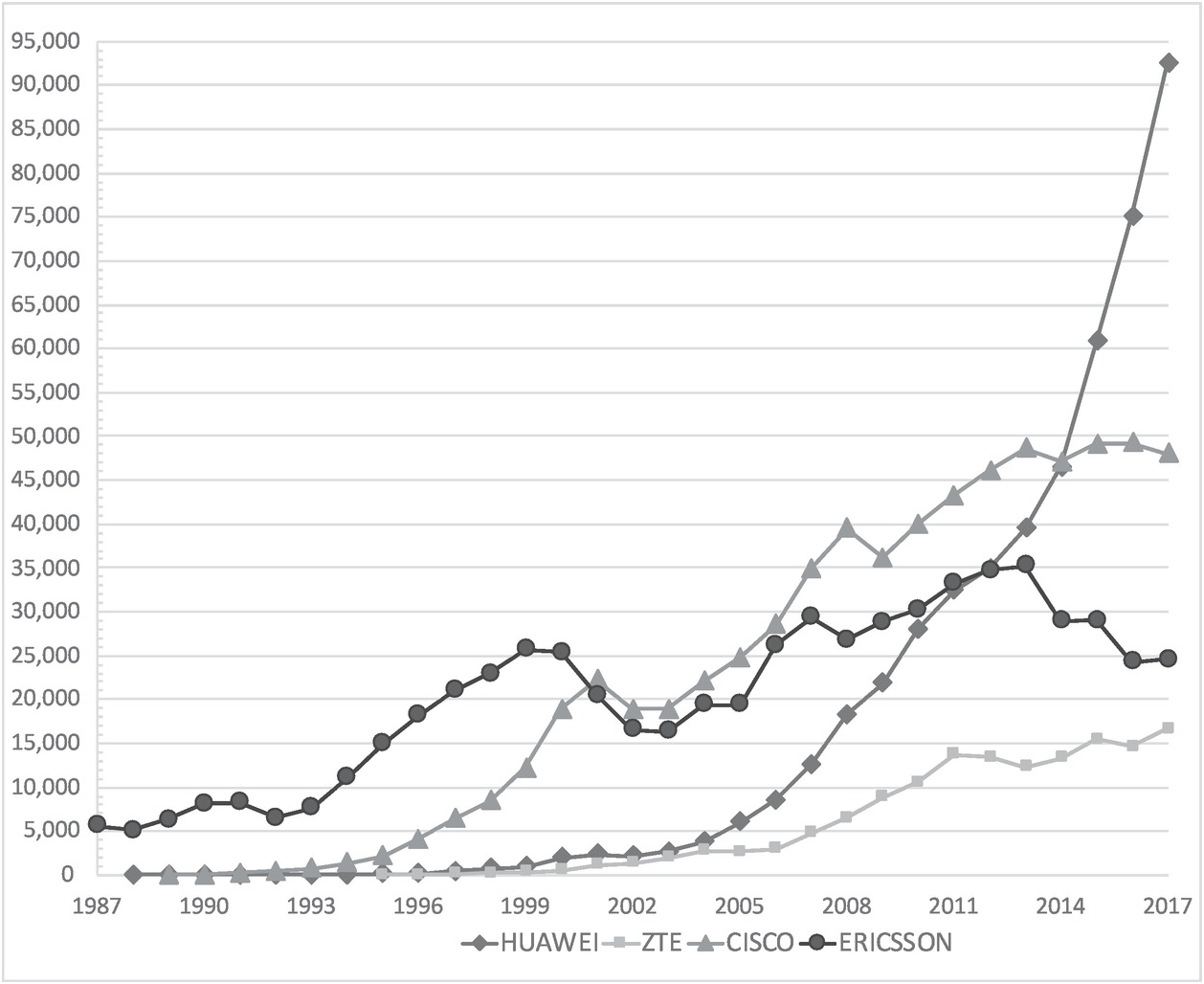

To make sense of the rise of Huawei graphically, we have created Figure 1.1. It compares the growth of Huawei since its foundation in 1987 to three other firms: Ericsson, its chief international competitor in the telecommunication industry, ZTE, its chief domestic rival in that industry, and finally Cisco, a chief rival in the networking and switching business.

Figure 1.1 nicely illustrates how Huawei’s higher growth rates have left all competitors behind. Huawei’s sales surpassed those of Ericsson in 2012 and those of Cisco in 2015.

As Huawei overtook Western rivals, taking further market share away from these players became strategically unviable. Governments across the world would not have allowed Huawei to become a monopolist. This is one reason why Huawei sought further growth in related industries. In 2002, it started to make handsets and related consumer goods as a contract white goods manufacturer, and since 2009 Huawei has sold smart phones under its own brand using the market leading Android OS (Gedda, Reference Gedda2009). The smart phone business has been Huawei’s fastest-growing segment since 2009, turning Huawei into the second best-known Chinese consumer brand in the Western countries behind Lenovo. In 2015, Huawei became the third largest manufacturer of smart phones in the world after Samsung and Apple, shipping 76 million units and gaining 8.7 percent market share (IDC, 2016). Huawei also entered the enterprise ICT equipment sector, producing everything from corporate networks, storage and security system, routers, IP telephony and video conferencing systems, to cloud solutions and other ICT services (Huawei, 2016b). Here, Cisco is one of the main competitors (Reckoner, 2013). In terms of the relative sizes, consumer sales (largely smart phones) is Huawei’s largest segment with 48.4 percent of sales, followed telecommunication network equipment and services sales to operators (carriers) with 40.8 percent, and the enterprise sector accounting for 10.3 percent of sales (Huawei, 2019).

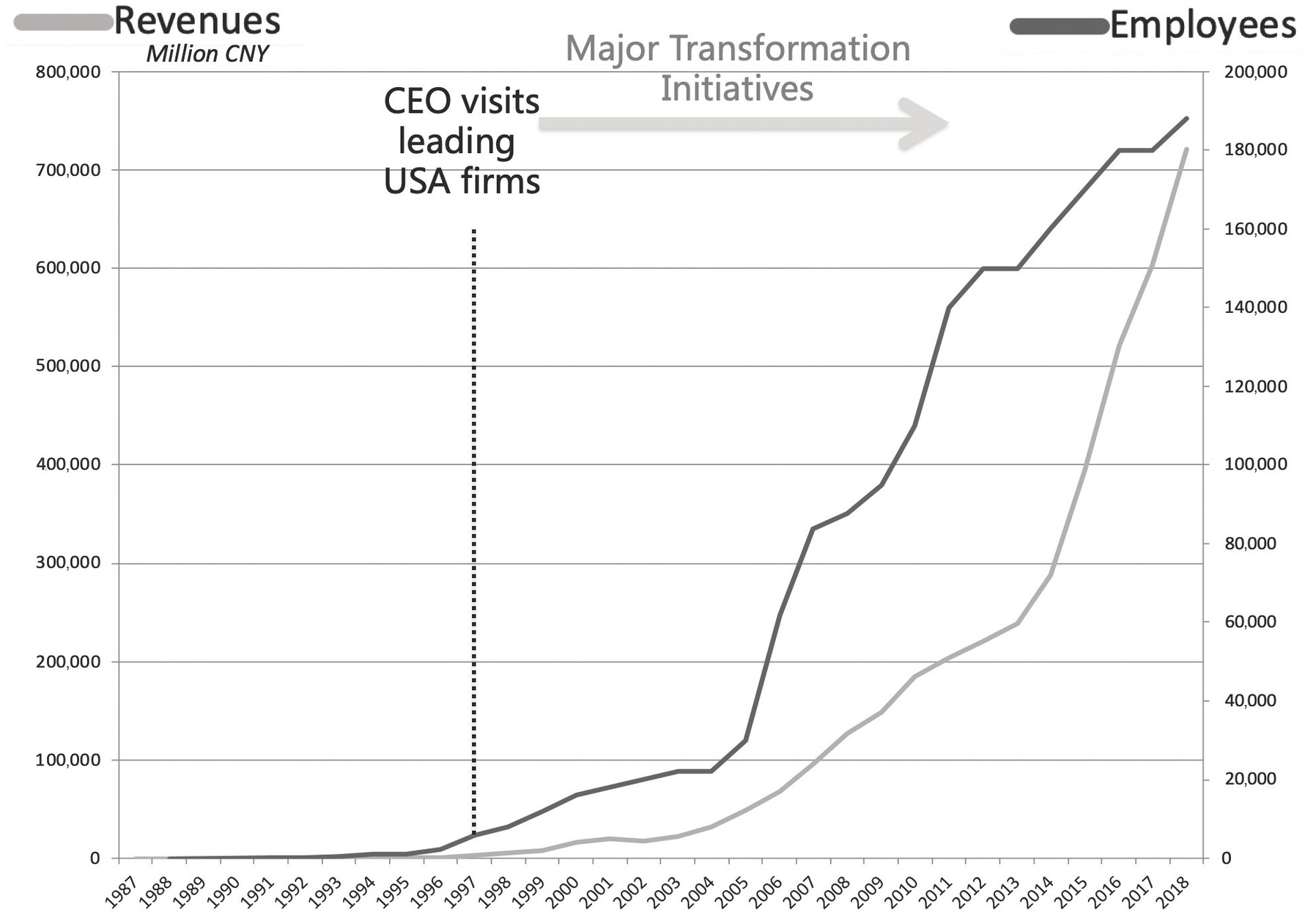

Huawei’s remarkable growth history is visible in Figure 1.2, which tracks the number of employees and total sales over time. The figure makes it plain that looking back over the past three decades, Huawei grew at moderate rates before 1995, subsequently growth rates accelerated until around 2003, and then there was another dramatic jump in growth rates. (Appendix A presents the exact numbers for each year.) These growth rates cannot simply be explained pointing to favorable market conditions that would have allowed all competitors to grow. Many Western competitors mentioned earlier declined over the past fifteen years, and Huawei undoubtedly became stronger as an organization at the expense of its Western competitors.

Figure 1.2 Huawei’s revenues and employees, 1987–2018, and the timing of major transformation initiatives

The chapters that follow analyze in detail aspects of Huawei’s transformation. To set the stage, it is useful to discuss a number of key features of Huawei that are in the background of all these transformation initiatives.

1.3 Key Features of Huawei’s Management Philosophy and Culture

When a company becomes as successful as Huawei and when it seems to have as strong as culture as Huawei has today, it is easy to fall into the trap of concluding that the firm possessed the values underpinning the culture from day one. Even if one can show that the founders already possessed these values at the beginning of the venture, it is a mistake to conclude that all employees who joined the firm would automatically embrace the same values. Huawei experienced significant organizational problems as the firm grew from 20 employees in 1991 to 6,000 employees in 1997 precisely because this 100-fold increase in staff numbers undermined the shared culture and philosophy that the founding team may have had. Our book details many initiatives whose clear aim was to create and then maintain a shared culture and esprit de corps as so many new employees were joining the firm every year.

Peter Williamson is one of the best-informed Western scholars of Chinese firms (Wan, Williamson, and Yin, Reference Wan, Williamson and Yin2015; Williamson, Reference Williamson2010). When asked to characterize strategy formulation at internationally known Chinese firms such as Alibaba and Tencent, Williamson explains: “Leaders of private Chinese firms simply made it up as they went along” (Williamson, Reference Li2015). Unlike firms in the West, a blueprint that the first private companies in China could follow in the high uncertainties in the Chinese environment did not exist. While China recognized the legitimacy of the private sector already in the 1988 revision of its constitution, property rights in the Western sense of the word were not as secure as they are in West from interference from the state (M. Zhang, Reference Zhang2008). Legally speaking, the Chinese constitution did not formally recognize the legality of private property until 2004 (Nee and Opper, Reference Nee and Opper2012; M. Zhang, Reference Zhang2008) and its institutional environment makes it more difficult than in the West to predict what policies the government will enact five years later (Lewin, Kenney, and Murmann, Reference Lewin, Kenney and Murmann2016). Williamson’s description of Chinese strategy-making at what now have become leading private companies is reminiscent of Deng Xiaoping’s often invoked aphorism “that he groped for the stepping stones as he crossed the river” (Vogel, Reference Vogel2013, p. 2). He used this aphorism to articulate his incremental approach to transforming the centrally planned economy into one that extensively used market mechanisms to allocate resources. Hence any well-read executive living China during the 1980s and 1990s would likely have come across this idea of approaching major changes incrementally.

There is strong evidence that Huawei’s cofounder and long-time CEO Ren Zhengfei also “made up” the strategy as Huawei developed from a small importer of telephone exchanges to a globally operating multinational. And just as in the case of Deng, Ren came to adopt the general philosophy that one needs to proceed incrementally in an environment where so many things change. While by no means a dominant view in Western academic writing on firm strategy, building on the work of the political theorist Lindbloom (Reference Lindbloom1959), James Brian Quinn (1980) has termed this approach as “logical incrementalism.” Ren admitted, “I am half-literate about technologies, corporate management, and financial affairs. I am trying to pick up and learn about these things along the way. So I must gather a number of people and let them play their own parts so that the company may move forward. Personally, I must remain modest, and depend on the collective power” (Tian and Wu, Reference Tian and Wu2015, p. 114).

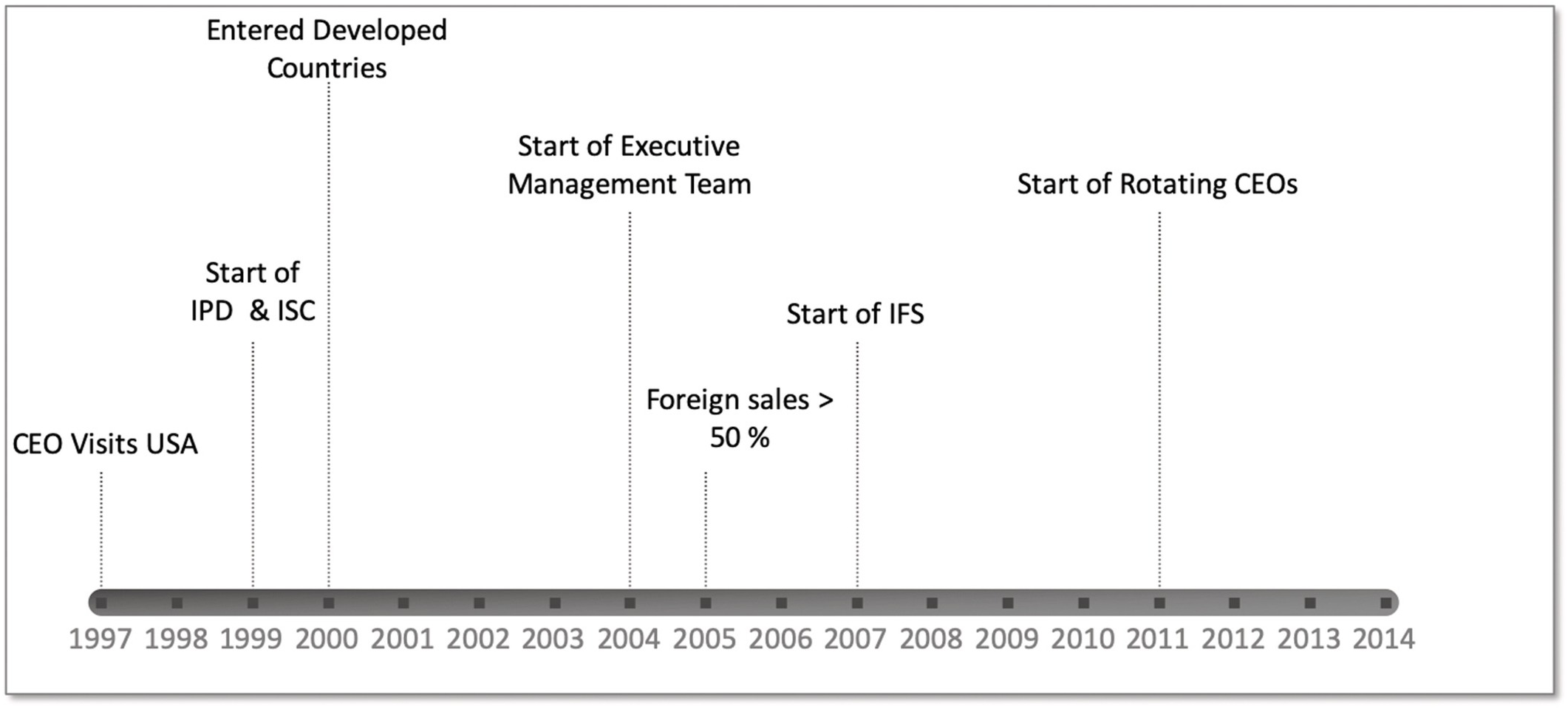

We will return later to the question of when and to what extent Ren used collective decision making during the first twenty years of Huawei’s existence. Tian and Wu (Reference Tian and Wu2015, p. 71) report that ever since Ren cofounded Huawei in 1987, he has been reading widely on history, economy, politics, society, humanity, literature, and the arts to find good ideas for how to improve the way Huawei is managed. He also has been talking to many different leaders both in China and in the West to refine his thinking about best management practices for the different stages of the firm’s development (Tian and Wu, Reference Tian and Wu2015, p. 122). Conversations in 1997 with CEOs of leading of US tech firms such as IBM, Lucent (Bell Labs), and HP, for example, solidified his conviction that Huawei needed a radical transformation of its operating procedures to continue its growth and catch up in efficiency with global leaders. To bring some precision to the discussion of how Huawei’s management philosophy developed, it is useful to trace the key management ideas Ren articulated for Huawei over time, where he likely got the ideas from, and when – during the thirty years of Huawei’s existence – these ideas became central in the way the firm was managed.

Since 1997 – ten years after the start of the firm – the two central management principles that the leadership of Huawei has believed to be key for being successful in the telecommunications industry are customer centricity and dedication of all employees to the corporate goals of Huawei (De Cremer and Tian, 2015). Ren leaves out no opportunity to communicate that customer centricity is the most important principle. In a recent interview with the Forbes China correspondent L. Yang (Reference Yang2015), Ren explained:

Our culture is very simple: staying customer-centric and inspiring dedication. In this world, our customers treat us best, so we need to devote ourselves to serving them. As we want to earn money from our customers, we must treat our customers well, and make them willing to give us their money. In this way, we establish good relationships with them. How can we serve our customers well? By working hard despite all the hardships we might encounter.

It is useful here to recall that corporate management always involves a complex tradeoff between different goals and stakeholder groups who to some extent have incompatible objectives. This is what makes top management always challenging and also explains why computers have not yet replaced CEOs. Consider one simple tradeoff: If you want to give employees a 30 percent increase in salary to increase their job satisfaction, you typically will not achieve the same profits that you would have made before the pay raise. Even if employees are more motivated, they are very unlikely to be 30 percent more efficient. This means that every company explicitly or implicitly has to trade off the different stakeholders – be they employees, shareholders, customers, government, or society at large.

However, to provide direction to employees regarding what goals they should focus on and prioritize when in doubt how to resolve conflicting goals, companies frequently elevate one stakeholder group to be the most important one. Under the leadership of Herb Kelleher (1981–2001), for example, Southwest Airlines told all managers that their top priority was to provide value to employees in the form of a superior and more fun work environment allowing the firm to attract a high-quality work force even though it only paid industry average wages (Hallowell, Reference Hallowell1996). Kelleher and his team believed that happy employees treat customers well, and happy customers in turn come back very often, filling the planes of the airline, which in turn allows the company to make very good returns for its shareholders (Gittell, Reference Gittell2003).

By contrast, inspired by economists such as Milton Friedman (1970) who argued that firms should be focused on increasing profits for shareholders, many American CEOs between the 1980s and the financial crisis in 2008 elevated the goal of increasing shareholder value to be the most important goal of their corporations. The logic in this approach goes like this: To make consistent profits, companies need to offer products and services that provide value to customers. If not, customers will abandon the firm and no profits will be made. Similarly, companies need to pay a fair wage to employees if they want to keep good human resources that allow them to provide products and services that are valued by customers. But without having profits for shareholders as the most important goal – so the argument goes – firms waste valuable resources and society is worse off. Having business organizations focus on shareholder value is seen as optimal for society. Fairly or not, Jack Welsh, who was the CEO of GE from 1981 to 2001 and under whose leadership the value of GE increased by 4,000 percent, was held up as the best example of this focus on shareholder value. In the case of Huawei, the focus is once again different: All employees since 1997 have been systematically told to prioritize customers over all other stakeholders.

Peter Drucker (Reference Drucker1974) is the management writer who popularized the idea that companies should center their efforts on satisfying customers. The logic of this view runs like this: Customers are the ones who are paying all bills. Without them, no benefits can be distributed among employees, shareholders, and the tax office. So the primary task of any company that wants to flourish should be to focus on continuously providing value to customers. If managers figure this out, everything else seen as relatively straightforward.

The first time a focus on customer centricity is mentioned in any of Huawei’s printed communications is in the context of drafting a constitution for the firm – the so-called Huawei Basic Law. The drafting process started in 1996 and was completed in 1998. (We have translated the Huawei Basic Law document from Chinese and provide the full text of it in Appendix D). The goal of the constitution was to apply the same principles of management to all different parts of the growing firm. There is no evidence that Ren got the idea of focusing the firm on customer centricity directly from Peter Drucker. According to C. Li (Reference Li2006), Ren learned the concept from Louis Gerstner, whom Ren visited in 1997 and who received worldwide fame in management circles when he saved IBM from collapsing by undertaking one of the most dramatic corporate transformations in the 1990s. Gerstner later described his change management approach in the book Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance?: How I Turned Around IBM (Gerstner, Reference Gerstner2003). Given that Huawei was started as a trading company and not a manufacturing firm, it is possible that from inception Huawei’s founders had a strong sense that to sell in a competitive market, it is necessary to have products that appeal to customers. There is some evidence that Huawei initially made up for its inferior products with excellent customer service (Tian and Wu, Reference Tian and Wu2015, p. 3). But it is quite clear that only when Huawei expanded rapidly between 1994 and 1998 did it ensure that all employees would embrace customers as an explicit management goal.

As is clear from the earlier Ren quote, the second most important value that Huawei has been trying to instill in all employees is dedication to their job at Huawei. Start-ups typically have to work hard just to stay alive. This was certainly the case at Huawei. Huawei outcompeted many Western firms by encouraging particularly the people in the customer service area to go the extra mile. Ren acknowledges that he has no hobbies other than reading and contemplating (Tian and Wu, Reference Tian and Wu2015, p. xxxv). He is clearly the living example of full dedication to Huawei. Tian and Wu report that “from the age of 44 to 68, Ren Zhengfei has kept his mobile phone on 24/7 and has spent one third of his time on business trips” (Tian and Wu, Reference Tian and Wu2015, p. xxxv). But as a firm grows and becomes more bureaucratic and successful, maintaining dedication to hard work among all employees typically becomes a challenge. Starting in 1997, as we are describing in detail in Chapter 6, Huawei implemented with the help of the Hay group and other consultants HR routines that would reward and promote those individuals who worked the hardest. Similar to GE, where until 2016 the worst 10 percent of all employees would be removed, Huawei started to systematically manage out people. Huawei developed a reputation that it would require employees to work such long hours that they would routinely spend the night sleeping under their desks. In the early days, Huawei handed out blankets and sleeping pads to take naps but employees would often also use them to sleep overnight (Tian and Wu, Reference Tian and Wu2015, p. xxxv). When in 2008 a few Huawei employees committed suicide, Huawei found itself in the middle of a public media storm for its alleged “mattress culture” that required employees to work so hard they may crack under the pressure (Tian and Wu, Reference Tian and Wu2015, p. 34). Huawei tried to explain to the public that a company like it that wants to be able compete with the best multinational companies in the world needs employees who work as hard as the best athletes in the country (L. Yang, Reference Yang2015). Huawei continues to be able to recruit top talent because the hard work that employees put in is rewarded through higher salaries, benefits, bonuses, and employee stocks. Anyone who has worked for Huawei for at least eight years and is forty-five years old can retire and keep their stocks in the employee-owned firm. However, anyone who leaves the company or wants to work for another company after retirement must give up their shares (Tian and Wu, Reference Tian and Wu2015, p. 229). Apparently, employees who no longer show “dedication” need to give up their shares as well. It is important to point out here that this approach of requiring employees to work much harder than at the average firm by definition cannot be imitated by every firm in the economy. Firms need to think carefully if they can offer employees sufficient rewards. Huawei can demand hard work because it has now become the leader of the industry and is attractive to new recruits. Those people who want a more balanced lifestyle simply leave.

One other special feature of Huawei is that, notwithstanding its size, it is not listed on the stock exchange but is a fully employee-owned company. While many listed companies in the United States give some stock to their employees, leaving aside professional law and accounting firms, there were only 2000 fully or in the majority employee-owned companies in the United States in 1990 (Hyde, Reference Hyde1991) out of roughly 5 million enterprises (U.S. Census Bureau, 1992). And none of them are as large as Huawei. In general, large employee-owned firms are a very rare species in Western economies and rarely seem to work well even though one can easily develop a rationale for why employees who own the company would be more motivated to work hard because all gains would go to them as owners. Observing that fully employee-owned companies rarely work, Western scholars have constructed elaborate arguments why they would not work. The simplest one is that employees would prefer to give themselves higher wages rather than invest back into the company, making the company not competitive over time (Ginglinger, Megginson, and Waxin, Reference Ginglinger, Megginson and Waxin2011). Another one is that when employees have a large stake in the company, decision making becomes too complex, as managers constantly have to trade off between different groups of stakeholders (Fama and Jensen, Reference Fama and Jensen1983; Jensen and Meckling, Reference Jensen and Meckling1976). In the case of Huawei, full employee ownership has worked very well, and as we argue in the chapters that follow, there are good reasons to believe that Huawei’s transformation capabilities have been helped rather than hurt by the collective ownership of the firm. As we describe in Chapter 6 on the transformation of its financial accounting system, Huawei has been able to raise a large amount of capital from its employees to fund growth. Yet is also clear that Ren did not fully foresee the benefits of this arrangement:

I designed the employee shareholding scheme soon after I founded Huawei. I had intended to knit all my colleagues together by a certain means of benefit sharing. At that time, I had no idea about stock options. I did not know that this had been a popular form of incentive for employees in the West, and there are a lot of variations. The frustrations in my life made me feel that I had to share both responsibilities and benefits with my colleagues. I discussed this with my father who had learned economics in the 1930s. He was very supportive. But no one had expected that this shareholding scheme, which came into being by chance more than by design, would have played such a big role in making the company a success.

Over the years, Ren reduced his own stock ownership to 1.4 percent (Huawei, 2015, p. 112; 2017, p. 99) but he continues to hold veto power of major corporate decisions. The rest of stock is owned by employees through a company called the Union of Huawei Investment and Holding Co. A few years ago, 81,144 of 180,000 employees held some stock in the “Union” (Huawei, 2017, p. 99). Stock is granted to employees based on their level of performance rather than on the egalitarian notion that every employee should receive some or even the same amount of stock. Unlike many of other practices that were imported from the West with the help of consulting companies, the way the employee ownership plan is set up and managed is clearly a homegrown development. Precisely how and why in the case of Huawei full employee ownership has worked while it has not worked well for large companies in Western countries is a fascinating topic that deserves to be investigated in more detail in a separate study. We can only offer some speculations: Perhaps the more collectivist Chinese context plays a role? Perhaps the strong meritocracy where higher performing individuals receive a lot more shares is key? Perhaps the fact the founder Ren Zhengfei is still around plays a key role because his special status prevents infighting among the different employee owner groups? Remember that Deng Xiaoping continued to be the most powerful Chinese leader even after he gave up his formal role. This would be unthinkable in a Western country. What is clear, however, is under the leadership of the founder who has reduced his ownership over the years and a team of longtime Huawei leaders and co-owners, Huawei has been able to make dramatic changes to the way it operates.

Another key part of Huawei’s culture is its long-term orientation. The goal of Ren has been to build an organization that would last for a very long time. One of the reasons why Ren has rejected going public has been because markets would not allow the firm to be managed for the long term (L. Yang, Reference Yang2015). Organizational changes are easier if a firm can wait five to ten years before the full benefits of the change are achieved. A few years ago, Michael Dell decided to take Dell computer private again because he came to the conclusion that the stock market would not allow him to make losses in the short term to finance the investments required to transform the company from mainly a PC maker into a cloud computing and service enterprise (Sherr, Benoit, and Thurm, Reference Sherr, Benoit and Thurm2013). Many of the transformation initiatives at Huawei that we analyze in this book took more than five years before most benefits were realized. A good example is the integrated product development (IPD) initiative, whose goal was to make new product development much more efficient and faster. This initiative ushered in a large cultural change and gave Huawei the confidence to carry out the subsequent major transformation. As Chapter 3 describes in detail, Huawei, after recruiting IBM to help with the initiative in 1999, spent the next three years in the preparatory stages to roll out the approach across the company. The first integrated portfolio management team (IPMT) was established in 2003 and subsequently the new routines for product development were spread throughout the company. Consistent with the philosophy and practices advocated by the total quality management movement in the United States in the 1990s (S. G. Winter, Reference Winter, Baum and Singh1994), Huawei has continued to refine and optimize the system of routines behind the integrated products development approach. Fifteen years after the start of the initiative, one of the measures to track improvement in product development still did not score at the target level set by the company, triggering another round of changes. When it comes to innovation, many companies in China – because of the environmental uncertainties – invest in projects whose benefits can be realized in the short term (Breznitz and Murphree, Reference Breznitz and Murphree2011; Chi-Yue Chiu, Liou, and Kwan, 2016).Testifying to its long-term orientation, Huawei has invested since 2012 in basic research initiatives whose benefits will take many years to come to fruition, as we know from the basic research efforts at Western companies such as Google and Microsoft, which all have units dedicated to basic R&D. The changes to the way Huawei has organized its R&D efforts are described in detail in Chapter 7.

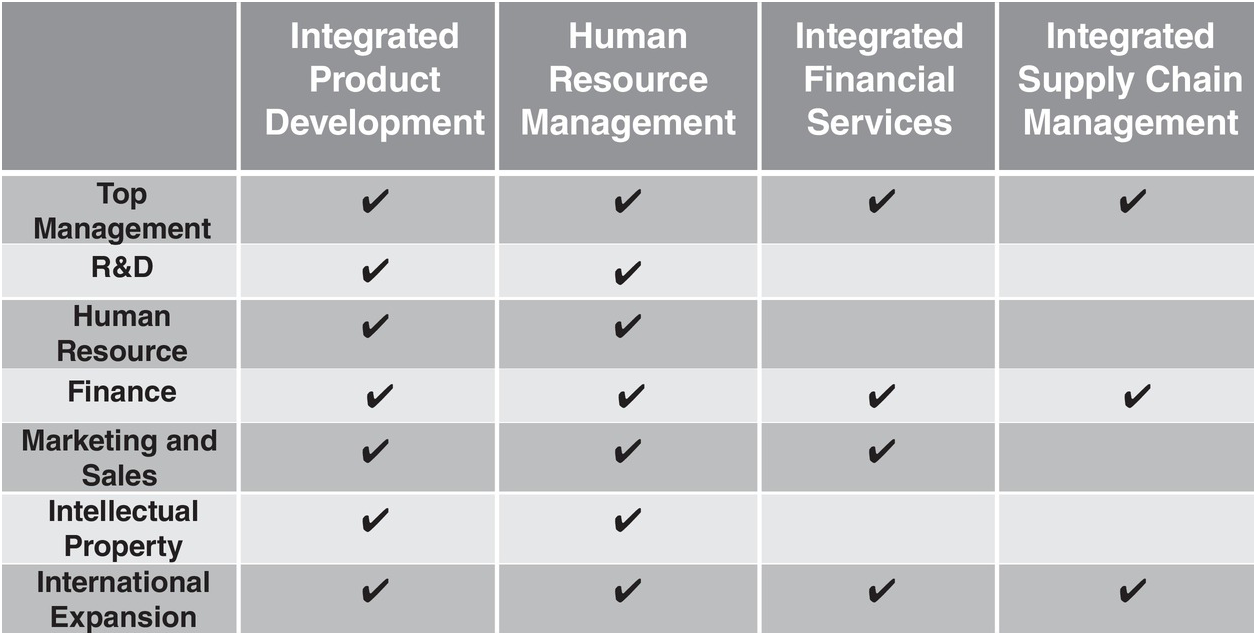

Openness to ideas and learning from around the world is another central feature of the corporate culture that Ren and his leadership team have been trying to instill in the company. We mentioned earlier that Ren was picking up ideas from his wide-ranging reading and conversations with other leaders. Before Huawei entered international markets after 2000, a development we describe in detail in Chapter 9 on internationalization, the firm imported best practices from Western firms. Huawei today can be aptly described as mixture of practices coming from the East and the West. Ren may have picked up lessons from Mao Zedong about first conquering the countryside before the cities and ideas about incrementalism from Deng Xiaoping. But present-day Huawei, unlike many other Chinese firms, is unimaginable without Western management know-how regarding how to create best in class organizational routines and structures. Deng Xiaoping initiated a program to send students to the United States to learn advanced technology so that China could catch up with the West (Vogel, Reference Vogel2013). When Ren and his leadership team visited top American firms including IBM, HP, and Bell Labs (Lucent), he realized how far Huawei was behind in best practices. Locking themselves up for the three days in a hotel room in Silicon Valley on Christmas Eve, they produced a 100-page document outlining the key learnings (Tian and Wu, Reference Tian and Wu2015, p. 53). Inspired by the transformation of IBM between 1991 and 1996 under Louis Gerstner, he then hired IBM consulting to help Huawei transform major aspects of its operation starting with the aforementioned integrated product development (IPD) initiative launched in 1999, the integrated supply chain initiative in 1999, and the integrated financial services initiative launched in 2007. IBM also provided materials for courses at Huawei University to train employees. Huawei in subsequent years also hired other Western consulting firms – the Hay Group, PriceWaterhouseCoopers, Mercer, Accenture, Fraunhofer – to help it develop best in class routines for its own customer-driven processes, human resources management, financial management, marketing management, and quality assurance (Tian and Wu, Reference Tian and Wu2015, pp. 118, 160). After World War II, many European firms hired American consulting firms to learn how to adopt American management ideas such as the multidivisional form (Kipping and Westerhuis, Reference Kipping and Westerhuis2012; McKenna, Reference McKenna, Kahl, Silverman and Cusumano2012). But the extent to which Huawei used Western management consultants to upgrade its routines and structures stands out.

Another feature of Huawei’s openness that makes it special among Chinese firms is its alliances with Western firms. Starting in 1997, Huawei also created product and technology partnerships with many Western firms including Texas Instruments, Microsoft, 3Com, Qualcomm, Siemens, HP, Symantec, and more (Y. Zhang, Reference Zhang2009). We should point out that the industry Huawei is competing in, telecommunications, requires a large degree of cooperation in the setting of standards that enable all phone users around the world to call anyone else. Without agreed-upon international standards, this would not be possible. This clearly mattered for the intellectual property rights strategy that Huawei developed over the years, which we describe in more detail in Chapter 9.

Before Ren founded Huawei, he studied civil engineering. Then from 1974 to 1983, he worked in that capacity in the military’s corps of engineers until the corps was disbanded in 1983 (Huawei, 2016a). Tian and Wu (Reference Tian and Wu2015, p. 78) come to the conclusion that “Ren had transplanted military tenets into the corporate culture of Huawei, including discipline, order, obedience, aggressiveness, unwavering courage, uniform will, and team spirit.” It is equally plausible that as avid reader and student of history, he learned the ideas about courage, obedience, discipline, and mass mobilization from Mao and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which he joined in 1978 (Pullar-Strecker, Reference Pullar-Strecker2013). In fact, Tian and Wu (Reference Tian and Wu2015, p. 62) report that, “Thirty years ago, [Ren] won the title of Model Learner of Chairman Mao’s Works, and the writings have certainly inspired him ever since.”Footnote 2 And they also report that Ren acknowledges having learned a lot from the CCP (p. 139). But let us not forget that, without ever having been a member of the military, many business executives use military language (creating a sales force, rallying the troops, fighting a battle, killing the competition, etc.), and that the entire field of strategy has its origins in writings about military strategy. Hence the evidence that Ren was deeply influenced by military culture is rather thin. There is no question that in early years Ren and the other leaders encouraged everyone at Huawei to be aggressive in trying to win customers and that Huawei often uses military language. Even much later, Ren said, “We don’t expect the manager we select through the competency review process to be a perfect person. A perfect person is a saint, or a Buddha, or a priest. We would rather pick strong fighters who can form an army” (Tian and Wu, Reference Tian and Wu2015, p. 101). Early Huawei had to be aggressive if it wanted to survive the competitive landscape of China of the late 1980s and early 1990s. Unlike in the case of Chinese telephone network operators, where the Chinese government created a tight oligopoly for state-owned companies (e.g., China Telecom) and prevented entry of private or foreign companies, the government had the opposite policy in the telecommunications equipment market until 1996 (C. Li, Reference Li2006). There it encouraged foreign firms to create joint ventures in China and virtually all big Western equipment firms came to China and competed fiercely. Furthermore, as mentioned before, the industry also saw hundreds of local Chinese start-up firms, which made the industry even more competitive.

But the history of the company reveals the competitive pressures in the early years of Huawei did not lead to the creation of a tightly centralized chain of command where every member of the organization would follow routines approved by the hierarchy. If anything, the organization resembled – to use military language – a loose organization of guerrilla fighters who improvised as they encountered different obstacles. As a result, different managers implemented quite different practices in whatever part of the organization they were responsible for. Perhaps the most revealing statement by Ren about the early period of Huawei from 1987 to 1997 is this:

In Huawei’s early years, I had left our “guerrilla commanders” alone in managing business operations. As a matter of fact, I didn’t really have the ability to lead them. During the first decade, we rarely had any operational meetings. I flew to different parts of the country to hear their reports, tried to understand their situations, and give them the “go ahead.” I listened to the brainstorming of the R&D staff. R&D was a mess at the time. We hardly had a clear direction, hopping around like a ball in the pinball machine. As soon as we heard customers who demanded improvement, we would exert great energy to meet the demand. Financial management was an even bigger challenge because I had not the least idea of finance. In the end, I had not got the relationship with finance staff right, and, to my regret, promotions for them had been rare. Maybe because I was not capable, I had set the hands of most people in the company free, who have therefore brought so much success to Huawei. I was then called a “hands-off boss.” I had wanted to be “hands on,” but I didn’t know how. Around 1997, different groups had emerged with their own leaders and agendas; hence alternative ideas and thoughts existed. No one could tell the direction of the company.

In 1997, Huawei organizationally was a mess. But Ren did not turn to consultants from the CCP or the Chinese military to bring better organizational practices and routines to Huawei. Instead, as mentioned earlier, he and other top managers visited US firms to gain ideas on how to fix the ever-increasing organizational problems. And he turned to American consulting firms, chief among them IBM, which before long had seventy consultants working at Huawei (Tian and Wu, Reference Tian and Wu2015, p. 164). What sets Huawei apart from most other Chinese companies is that the company married its Chinese origin with the most advanced Western routines and practices.

A year before Ren and senior leaders went to America, Huawei also started an effort to counter the increasingly diverse practices that the various managers had created. Through a collective process, Huawei began to formulate a “constitution” for the firm that would be binding for everyone working there. A professor from Renmin University at the time was helping the marketing department, and some of his Renmin colleagues were recruited to help draft this constitution that often is referred to the Basic Law or charter of Huawei (Huang, Reference Huang2002).Footnote 3 The process of creating the Basic Law took three years from 1996 to 1998. John Kotter (Reference Kotter1996), the Western expert on change management, would have been impressed with the way Huawei’s top management created a sense of urgency for the process and created a guiding coalition and vision for the change that was then systematically implemented over many years. We will describe the contents of the Huawei Basic Law in the next section because it is a crucial piece of evidence for the central argument of our book that Huawei has a special ability to create routines and break routines when they no longer serve the strategic goals of the company.

One way in which Ren got the organization to accept change was to start emphasizing the need for organizational “criticism” and “self-criticism.” Here, Ren took a chapter straight out of the playbook of Mao campaigns to unify the party members behind his plans (Dittmer, Reference Dittmer1973). Tian and Wu (Reference Tian and Wu2015) explain:

In 1997, … Ren Zhengfei started to advocate self-criticism more often, and its meetings of criticism and self-criticism, the so-called “democratic meetings” which had lasted 10 years, were institutionalized and extended to every level and part of the organization. This is a typical CPC practice for organizational development and has helped Huawei in developing its own managers and teams.

Without question, the extensive organizational transformation of Huawei during the period from 1997 to 2005 led to a massive centralization of power. Ren achieved a similarly powerful position to the one that Bill Gates possessed at Microsoft in the 1990s. The hands of Ren were clearly on the wheel as he brought in foreign consultants and insisted that Huawei follow the advice of the consultants and copy exactly Western practices unless the consultants themselves approved modifications for the Chinese context. Ren explained:

In this process, we don’t want any skeptical people or those who believe they are wiser than the IBM advisors. We must guarantee that there’s proper understanding and consensus, and there must be active involvement. We must eliminate those who think they are smarter than IBM and smarter than anyone else in the world.

As part of the change campaigns, 100 mid-level and senior managers left the company or were demoted, or removed when they became a roadblock in the direction Huawei wanted to move. Yet in the process of becoming the indispensable leader, Ren became clearly overburdened. Having his mobile phone on 24/7, ready to troubleshoot issues that might flare up in a globally expanding firm, he came to suffer from severe physical and mental health issues. Tian and Wu (1995, p. 154) report that Ren between 1999 and 2006 developed “hypertension, diabetes, two cancer operations, and depression.”

A true sharing of power at Huawei started only around 2004 with the creation of an executive management team. Chapter 2, which covers transformation of the top management team, provides many details on how Huawei created new routines and practices to become less dependent on the founder. Perhaps the most the interesting one is the system of rotating acting CEOs that was instituted in 2011. Ren comments:

In recent years, we have instituted democracy first among senior management, and then the whole organization has become democratic. Decisions are now made collectively. The process is slower, but we have made fewer mistakes. Any idea must be marinated and communicated gradually throughout the company, and we do not expect any change overnight. It will produce great power if it is implemented after being accepted by all in the company.

By 2005, more than 50 percent of Huawei’s sales came from international markets. Huawei’s corporate routines and practices at this point needed to be able to accommodate employees in many foreign companies around the world. At that time, Ren started to stress the value of tolerance. For over ten years now, Huawei has added tolerance for people who have other ideas as another key pillar of its corporate culture. Here is one of the many statements Ren has made to communicate the important of tolerance:

People are born different. To be tolerant means to accept differences. A manager must show enough tolerance to draw together people with different characters, skills, and preferences in order to create synergy, and therefore, fulfill the mission of the organization. … To be tolerant is a sign of strength; not weakness. Tolerance, as part of a plan, means the ability to take a step back in order to reach a certain goal but still hold on to the initiative. Of course, it is not tolerance if one has no other choice and is forced to do so.

Since Huawei is now operating in 170 countries, being inclusive of different national cultures is important to motivate employees who are not Chinese. But Ren also connects tolerance of other people as a key ingredient for stimulating innovativeness, as Huawei has tried to become a leader in innovation in recent years:

China still has no soil for another Steve Jobs. We are not tolerant enough, and we do not protect intellectual properties well enough. Millions of Chinese mourned the death of Steve Jobs, but we wonder why we cannot tolerate Chinese business people? Innovations are only possible on the ground of tolerance. So are great business people.

For a Western audience, it may appear strange that tolerance is elevated to an important corporate value since Western societies have worked on institutionalizing tolerance for hundreds of years. The quote makes clear that Ren believes that in the Chinese cultural context, a company needs to stress tolerance to get managers to pay attention to all good ideas no matter where they come from.

One important way in which Huawei has tried in recent years to encourage tolerance of other people’s views is by institutionalizing oppositional voices. Under the strategy development committee, Huawei has set up a “Blue Army” department. The “Red Army”Footnote 4 are the managers who officially are in charge of the company. The Blue Army role is to review the strategy plans of the Red Army from a different perspective. Furthermore, the department is supposed to organize debates and simulations that seek disruptive technology alternatives (Tian and Wu, Reference Tian and Wu2015, p. 213). More recently, the Blue Army department has been asked to help push the practice beyond the corporate level strategy process to the business units by helping the business units set up their own Blue Army teams.

We offered this review of Huawei’s management philosophy and culture to set the context for our book. Furthermore, instead of depicting the firm as always having the same values, we wanted to show that some values changed over time as the firm faced different strategic problems. Perhaps the most dramatic change concerned decision making at the firm. After a pronounced period of centralization and concentration of power in the hands of Ren during the period from 1997 to 2003, Huawei has decentralized power and set up a process where strategic questions are debated rather than decided by the CEO.

1.4 Creating Routines and Breaking Routines

“We don’t rely on individuals to lead the company. We use the certainty of rules to deal with the uncertainty of results.”

The central argument we are making in this book is that Huawei has developed a transformation capability through dynamically creating routines and through breaking routines when they no longer work well as the company grows to a different scale and faces a different strategic context.

The term “routine” is used in an expansive way in this book. We do recognize that “organizational routines” are highly diverse in their origins and functions, and in an organization the size of Huawei this potential variety is likely going to be well represented. It is a serious mistake to try to squeeze the variety into a single, small conceptual box. However, the important task of pointing out key distinctions among cases is best left to the discussion of the cases themselves. What deserves emphasis here is the unifying theme that justifies the use of a single term across a wide range of phenomena, and that theme can be summarized as follows: At any given time, a very large proportion of an organization’s knowledge of how to do concrete things is stored in its routines. The information thus stored is the fruit of experience, and is analogous to habit or skill at the individual level. Situations where the organization lacks an applicable routine for a task it confronts are marked by groups of people standing around talking, discussing around a conference table or otherwise communicating about how to address the task. They have to do that because there is no obvious answer available. The advantage of developing a routine then can be called upon every single time the same how question arises to the extent that it makes those interactions unnecessary. Developing such a routine that solves the problem at hand requires effort, and initial solutions may not be that good and require modifications until it works sufficiently well.

But as time goes by, it becomes increasingly likely that, for one reason or another, the existing answer falls short of alternatives that could be discovered. In that case, the routine should change; those conversations that have been efficiently avoided for a long time will have to take place. That is the process of change, the process of breaking routines and creating new ones. It is a very different thing from the exercise of established routines. Of course, there can be habits, skills, rules, and attitudes that shape the change process itself, and this, too, is an important part of the Huawei story. One very simple example from our research serves to illustrate this theme. When a new employee comes aboard in an organization, it is necessary to adjust the record-keeping to reflect that the individual is now an employee. A part of that process is providing an ID number for the employee. There are many ways to do that; there are relevant criteria, and it is clear that it would not be reasonable to have a thorough discussion of all the possibilities every time there is a new employee to deal with. A routine is needed, but what should it be? Huawei’s early practice was to assign numbers based on the time of hiring. This seems sensible, but it has an important consequence, quite possibly unintended: An individual’s seniority in the company can be inferred from his or her employee number. The pros and cons of making the seniority information so readily available are something that can be discussed. In the Huawei discussion, the “cons” won on the basis of the argument that the established routine for employee numbers gave an unintended boost to the company’s hierarchical culture – so the company switched to a routine based on random assignment of employee numbers.

The most elaborate example of creating routines to standardize practices across the different managers of the firm is the formulation of a firm constitution, the Huawei Basic Law, from 1996 to 1998. Huawei attempted something similar to what Ernst Abbe did in 1896 when he wrote the foundation statutes for the Zeiss Company, which continues to be a leading optics company that produces scientific microscopes and nowadays camera lenses for smart phones. Abbe wanted to lay down clear rules for how the company was supposed to be managed in the future and also provide the reasoning and intentions behind the rules (see Buenstorf and Murmann (Reference Buenstorf and Murmann2005) for details on the Zeiss document). The difference was that Abbe wanted to lay down rules for the period after he was dead, and he codified mainly existing practices. Abbe wrote the document himself, as he owned 100 percent of the shares of Zeiss that he transferred into a foundation. In the case of Huawei, the purpose of the three-year collective process was to bring agreement about how the firm was going to reduce the diversity of practices and develop a common approach. Several drafts were published for comments from members of the organization, and as previously mentioned a team of six Renmin University academics helped to draft the document (S. Yang, Reference Yang2016).Footnote 5 Ideas that the Huawei leadership team acquired during their 1997 US trip may have shaped the wording of the final document a bit.

For those who will find it beneficial to examine the details of Huawei’s Basic Laws, we have translated the 9000-word, 103-article document and offer it for the first time in English in Appendix D. Here we want to give a brief overview of key ideas in the document and provide a sense of how the Huawei Basic Law was a tool to help bring standardized routines and practices across the rapidly growing firm.

Part I (Articles 1 through 20) sets out the vision of becoming a world-class equipment supplier, describes values for Huawei – many of which we already described earlier – and it identifies some key intermediate goals, for example, to develop independent intellectual property. Throughout the articles that follow, the document not only sets out routines to be followed, but frequently aspirations for the various functions of Huawei are articulated and the rationale for them is also sketched. Every top- and middle-level manager was supposed to read and master the Basic Law so they would have a shared understanding of where Huawei wanted to go and what methods of getting there would be condoned and what methods would clearly be in violation of the Basic Law.

Part II (Articles 21–25) sets forth basic operating principles. Article 25, for example, articulates that “customer satisfaction” should be the yardstick to value all work. Notice that the idea of customer centricity only appears in Article 25 and not Article 1, highlighting that this principle was elevated later to be the most important principle of Huawei. Article 26 articulates a key resource allocation rule and differentiates Huawei from many other local firms in the telecommunication industry. It guarantees that at least 10 percent of sales are allocated to R&D. Huawei has implemented this rule consistently. In 2018, 14.1 percent of sales were allocated to R&D. Article 27 sets forth the organizational structure for R&D, which we will describe in detail in Chapter 8. Article 37 sets forth a clear rule that the company will not engage in unrelated diversification, a principle that the firm has followed since 1998.

Part III (Articles 39–54) articulates key features of the organization structure and it sets up aspirations for the level of competence to be achieved in the different functions of the firm. What comes out very strongly in these articles is the attempt to centralize control and not to allow individuals to run their own fiefdoms.

Part IV (Articles 55–73) articulates human resources aspirations and policies. After announcing that development of superior human resources is key for the success of the firm, the articles in this section focus on how to create a fair and transparent human resources system. We describe in Chapter 6 in detail how Huawei went about achieving this. Here we simply want to highlight one important routine in Article 72. It stipulates a job rotation policy for senior executives to give them broader experience.

Part V (Articles 74–99) sets forth principles for the management control system of the company. The key idea behind the rules is to strengthen the control of the center of the entire organization. The 25 articles touch on the areas where the firm needs to make real improvements and articulates principles that should be followed to make it happen. One way to interpret this section is that it articulates a collective agreement for the various transformation initiatives that were started in 1998 including the IPD, integrated supply change management and HR system initiatives that we analyze in this book. Article 78 sets the goal of engaging in total quality management and stipulates that the routines that Huawei will establish for this purpose will comply with ISO-9001 requirements. Article 79, among other things, sets a specific goal, namely that a product on average will run 2,000 days without fault.

Part VI (Articles 100–103) outlines that Huawei needs to balance using routines with introducing new routines. It also makes stipulations for who should succeed current managers, how they should be trained, and finally when and how the Basic Law is to be revised. Article 100 articulates the need to proceed incrementally with changes, emphasizing, “We must develop and inherit.” The final article (103) stipulates that the Basic Law is supposed to be revised every ten years. Here again the document is different from the Zeiss foundation statutes, which only allowed changes under exceptional circumstances (Buenstorf and Murmann, Reference Buenstorf and Murmann2005). Huawei’s Basic Law sees itself as a short- and medium-term articulation of the organizational vision and key routines. The Huawei document is explicit that to achieve the vision of becoming a leading telecommunications company, the company needs to change its routines whenever this is deemed necessary.

In fact, what makes the Huawei philosophy different from Zeiss foundation statutes is that it much more explicitly sees the need to constantly break routines in parts of the organization to remain able to adapt to new circumstances. Reflecting on the history of Huawei, Ren notes:

We have been alternating from stability to instability, from equilibrium to non-equilibrium, from certainty to uncertainty. We are doing this over and over again to maintain the company’s vitality.

As far as we can tell, Huawei never published an updated Basic Law document. Instead it created separate manuals for the different functions of Huawei where some parts of Basic Law reappear but some old routines are clearly broken and replaced by new principles and routines.

The chapters in this book provide many striking examples of such de-routinization of existing practices (Edmondson, Bohmer, and Pisano, Reference Edmondson, Bohmer and Pisano2001). At the level of the top management, Huawei centralized more power around its founder and CEO in the period from 1999 to 2003. As is described in Chapter 2, this pattern was broken in 2003. With the help of the consulting firm Mercer, Huawei developed new routines for how the highest level of the firm operated. It allocated more decision-making power to an eight-member executive management team, which had the responsibility for strategic decision making and worked together with the CEO to lead the firm. The chair of the member committee rotated every six months and the chair functioned at the same time as the chief operating officer (COO). This arrangement lasted from 2004 until 2010. In 2011 it was replaced by a different decision-making structure. Huawei created a thirteen-member board of directors and the CEO and the founder became one of four deputy chairmen of the board of Huawei. To transfer even more power from the founder, a rotating acting CEO arrangement was created. Three senior executives started to take turns being the acting CEO, rotating in and out of the acting CEO position every six months. The three rotating acting CEOs and four executive directors (one of them was Ren) from then on formed the executive committee, which replaced the executive management team at the corporate level.

Every start-up that manages to survive the early years learns quickly that to scale operations, learning routine ways of dealing with particular tasks is typically the only effective way of proceeding (Rao and Sutton, Reference Rao and Sutton2014; Szulanski and Jensen, Reference Szulanski and Jensen2008; S. Winter and Szulanski, Reference Winter and Szulanski2001). Often the initial routines come about through experimentation or they are imported from other firms where some of the founders had experienced certain routines. Huawei developed routines in the first eight years that focused on coordinating work more within the business functions, procurement, R&D, sales, production, etc., than across the business functions. As the firm grew from 1,200 people and CNY 885.21 million (106 million USD) sales in 1995 to 8,000 people and CNY 5,960.95 million (720 million USD) million in sales in 1998, the existing routines were no longer effective, as product development times increased, development costs soared because many products failed, and customers frequently did not receive products on time.

As mentioned earlier, the top management then embarked on a process to import from the West best practice routines for product development and supply chain management. In both cases, the new routines that were introduced into these two functions broke with existing routines that coordinated mainly within the specific function. The newly created routines coordinated much more extensively across functions. In the case of the integrated product development (IPD) initiative, the CEO insisted that Huawei employees copy exactly the routine templates that IBM consultants provided to Huawei. Unlike the “copy exact” strategy of Intel where the firm insisted that a second factory making a particular generation of chips copy exactly the design of the first factory (Winter, 2010), IBM consultants made a few changes to the IPD templates copied from IBM’s practices to accommodate the context of Huawei in China. But Huawei’s leadership insisted employees had to copy exactly what the IBM consultant told them. To overcome resistance to the change, the CEO repeatedly told employees that Huawei “cut its feet to fit in the shoes” (Yu, Reference Yu2013) of the IBM templates. The resistance to the proposed new routines was grounded in the fact that Huawei’s gradually grown routines would be broken by the new system.

Before IPD product development followed serial routines. Marketing and Sales sent requests for new products, R&D next would develop technological solutions that were handed to manufacturing and logistics would organize shipping to customers. Frequently, the products did not work as promised, because there was no back and forth between functions to ensure the technology worked well for customers. What is more, the same kinds of products were developed over and over again because different sales and marketing groups sent requests for similar products to R&D, which treated them as independent products. In 1997, there were over 1,000 version numbers of often similar products (Liu, Reference Li2015). As a result, product development costs increased dramatically and were out of line with international competitors. The new IPD routines required that cross-functional teams were formed to interact frequently during the product development phase and to prioritize what products were to be developed to avoid duplication. Marketing had misgivings about this change in routines, because under the old routines when a product failed, marketing could simply blame R&D as marketing was not involved in the product design phase. In the new IPD system, marketing was deeply involved in the design stage and could no longer pass the blame to R&D. The breaking of old routines initially caused product development to be even slower, but before long the new more coordinated approach to product development increased efficiency significantly. The average time to market for a new product decreased from 74 weeks in 1999 to 48 weeks in 2003 (L. Zhang, Reference Zhang2012).

A similar lack of coordination across the different business functions existed between sales, procurement, product, and delivery before Huawei hired IBM consulting to help it bring its supply chain practices up to world-class standards starting in 1999. The integrated supply chain (ISC) initiative broke existing routines that focused on coordinating within functions rather than across. Before 1999, the sales function took orders from customers without considering whether plants had the capacity to make the product in time. This often led the sales department to promise delivery dates that could not be kept by production and outbound logistics. The production department in turn had no sophisticated way to predict demand, and hence it was difficult to plan production much in advance. The procurement department signed up suppliers without having good forecasts on how many parts of a given type were needed. This led some parts to be oversupplied and some parts to be undersupplied. As a result of this weak coordination, the ratio of timely delivery at Huawei was only 50 percent, whereas the average level for telecom equipment manufacturers worldwide was 94 percent (Chapter 4 provides details). The ISC initiative replaced functional silos with many cross-functional routines to improve the efficiency of the supply chain. Just as product development was greatly improved through the deployment of state-of-the-art information technologies, the various functions of Huawei involved in supply chain were also much better coordinated through the introduction of much more sophisticated IT tools for customer relationship management, resource planning and procurement tools that helped break the functional silos.

Consistent with the routinization goals articulated in its Basic Law, Huawei rolled out between 1998 and 2007 under the name of “Four Standardizations” uniform financial accounting principles. This was done first across its offices in China and then across the world. Following a competitive selection process, KPMG consultancy was hired in 2000 to help with this process. By 2007, there was a strong perception that some of Huawei’s routines connected with financial accounting had become too rigid. Huawei had been moving more and more from selling equipment to selling turnkey solutions all around the world. The pricing routines that worked relatively well for selling equipment did a rather poor job in predicting with accuracy what projects would make money and what projects would not. Under previous routines, sales people would develop contracts with little input from the finance department. Furthermore, as competition in the global telecommunications industry increased, becoming more efficient in the management of cash flows became a key goal for Huawei. There was a strong perception that this could only be achieved by creating businesses practices that integrated financial analysis more deeply into the various business departments such as marketing, sales, supply chain management, and so on. Again IBM consultants were hired in 2007 to help with a multi-year program of replacing existing financial planning routines with coordinated routines that allowed Huawei to know better what projects would be profitable, how to contain risks and how to reduce working capital requirements.

Huawei also developed and refined its HR routines well beyond what was articulated in the 1998 Basic Law. In a drive to continuously upgrade its human resources, HR practices were later codified in training manuals (Huang, Reference Huang2016) and in courses given in its in-house training facility, Huawei University. In the process of creating new routines, Huawei also broke with old routines. As previously alluded to example make this point well: To help counter the hierarchical culture of Huawei, the company stopped assigning employees numbers based on the time of hiring. Instead it randomly assigned employee numbers so that it would not be longer possible to see who was more senior simply by knowing someone’s employee number. Even more significantly, to allow foreign employees to get similar rewards as Chinese employees could through the employee ownership scheme, Huawei changed the routines for sharing profits across its employees. Chinese law restricted employee ownership to Chinese nationals, and for this reason a different mechanism entitled time unit plan (TUP) had to be developed to share profits with an ever-growing number of international employees (details of these changes are described both in Chapter 5 and 6).

Organizational structures are formal ways to coordinate the actions of individual employees in the firm, and they shape routines to a considerable extent. Any significant change in the organizational structures entails the breaking of existing routines. As Huawei expanded from 50 to 150,000 employees, the organizational structures for achieving its R&D function were changed significantly, disrupting existing routines. When Huawei initially started to develop its own products in 1992, this R&D was carried out as part the manufacturing division. Soon Huawei noticed that with the rise of mobile phones, transmission was increasingly moving from analog to digital technology. Hence it decided to create a special R&D division in 1993 to focus on digital technology outside the manufacturing department. The digital unit formed a separate department reporting directly to the CEO. As the scale of R&D efforts increased, Huawei broke this structure in 1995 and created a central R&D department that coordinated all R&D efforts. This structure was again broken with the introduction of the integrated product development routines (see Chapter 8 for details on all major structural changes to the R&D function).

The Basic Law expressed the clear goal of developing independent technology and independent intellectual property (IP). Before 1995, Huawei filed no patents at all. In 2015, Huawei was the fifth largest filer of patents in Europe (European Patent Office, 2015) and in terms of number of patents granted in the USA held position No. 50 (IPO, 2015). But creating the organizational capability to file and receive so many patents proved rocky. Huawei initially formed an IP function in 1995 as part of the newly formed Central R&D department. Four years later, when Huawei created a Legal Affairs Office at the corporate level, the IP function was moved out of central R&D to become a unit of the Legal Affairs Office. Two years later, the IP unit was split again and was moved back to Central R&D. Across all these moves, it was difficult for the leaders of the IP department to change the routines of researchers at Huawei who were not used to keeping written notes of their works and filing patent applications. Huawei also could not make up its mind how it was going to implement its IP strategy until it was sued in 2003 by Cisco in the United States for patent infringements. The case was later settled without admitting guilt. This event clearly served as a wake-up call for the entire organization that it needed to take the filing of IP and the recognition of other firms’ IP much more seriously.Footnote 6 Huawei has been paying large amounts of licensing fees to Western tech companies ever since. The CEO then set much more specific five-year plans for how many patents Huawei should file to build up its own IP portfolio and help it negotiate more favorable deals with holders of other IP that Huawei’s products build on. With the support from top management, the routines of R&D process were modified to make it easier to obtain patents. Filling patents became KPI for all research teams and embedded in the performance appraisal routines of individual researchers. Similarly, every new product development project would now have a routine investigation of what IP was owned by other firms. As the scale of patent filings and patent analyses increased, the IP department once again was moved back from Central R&D to the Legal Affairs department. As this short history of Huawei’s IP office makes plain, only by 2003 did Huawei make a clear commitment to disrupting existing routines in the R&D function so that the firm would become a very large holder of IP in the telecommunications sector.