English is an official language in the Philippines, along with Filipino, a standardized register originally based on Tagalog (Gonzalez Reference Gonzalez1998). The Philippines were a Spanish colony for over three centuries, but when the Americans took control in 1898, they immediately implemented English instruction in schools (Gonzalez Reference Gonzalez2004). It became much more widespread among Filipinos than Spanish ever was, and by the late 1960s, Philippine English was recognized as a distinct, nativized variety (Llamzon Reference Llamzon1969). It is widely spoken throughout the country as a second language, alongside Filipino and approximately 180 other languages (Lewis, Simmons & Fennig Reference Lewis, Simons and Fennig2016). It is also spoken in the home by a small number of Filipinos, especially among the upper class in Metro Manila (Gonzalez Reference Gonzalez and Noss1983, Reference Gonzalez, Villacorta, Cruz and Brillantes1989) and other urban areas. There is a large body of literature on Philippine English. However, relatively few studies have focused on its sound system. The most detailed phonological descriptions of this variety have been by Tayao (Reference Tayao and Lourdes2004, Reference Tayao, Lourdes, Lourdes, Bautista and Bolton2008), although there have also been previous sketches (Llamzon Reference Llamzon1969, Reference Llamzon, Lourdes and Bautista1997; Gonzalez Reference Gonzalez1984). There has been very little phonetic research on Philippine English, apart from some work describing the vowel system (Pillai, Manueli & Dumanig Reference Pillai, Manueli and Dumanig2010, Cruz Reference Cruz2015).

Previous work on Philippine English phonology has described social class-based variation among speakers, which is linked to different levels of substrate influence from various Philippine languages. Tayao (Reference Tayao and Lourdes2004, Reference Tayao, Lourdes, Lourdes, Bautista and Bolton2008), following Llamzon (Reference Llamzon, Lourdes and Bautista1997), classified speakers into acrolectal, mesolectal, and basilectal groups based on their education levels, professions, and language usage in different domains. The acrolectal group included educated professionals who use English both at work and at home, the mesolect included educated professionals who use English often at work but not at home, and the basilect included working-class people who use English only occasionally at work. The first languages (L1s) of the participants in these groups were not identified, so it is not possible to trace substrate influence to a specific language in these descriptions. As Tayao (Reference Tayao and Lourdes2004: 86) noted, there is likely phonological variation among speakers from different language regions (e.g. L1 Tagalog vs. L1 Cebuano speakers) that should be further explored.

Within broader frameworks of World Englishes, Philippine English has been classified in various ways. It is an Outer Circle variety according to Kachru's (Reference Kachru, Quirk and Widdowson1985, Reference Kachru2005) model, and in Schneider's (2003) dynamic model, he classified it as a variety in Phase 3 (nativization) of the five-phase cycle. However, Filipino scholars have variously argued that it is in Phase 3 (Martin Reference Martin, Buschfeld, Hoffman, Huber and Kautzsch2014a), Phase 4 (endonormative stabilization; Borlongan Reference Borlongan2016), or at the beginning of Phase 5 (differentiation; Gonzales Reference Gonzales2017). Part of the reason it is difficult to classify is that Philippine English has not developed uniformly across different segments of the population. As Gonzales (Reference Gonzales2017) observed, previous work has usually not explicitly stated which variety is under study, but there are actually multiple Philippine Englishes spoken by people from different geographic, ethnic, and social backgrounds. In fact, the development of distinct dialects, and their ideological associations with local identities, is one reason he argued that Philippine English has now entered Phase 5.

Martin (Reference Martin2014b) conceptualized the different levels of development of Philippine English through an extension of Kachru's circle model, recognizing that there are Inner, Outer, and Expanding Circles of English even within the Philippines. These circles seem to roughly correspond with the three sociolects identified by Tayao (Reference Tayao and Lourdes2004, Reference Tayao, Lourdes, Lourdes, Bautista and Bolton2008), but they may not overlap completely, because Martin (Reference Martin2014b) also takes into account the language attitudes of the speakers. For example, Inner and Outer Circle speakers might both be well educated, but Inner Circle speakers proudly accept Philippine English as a legitimate variety with internal norms, whereas Outer Circle speakers still tend to orient themselves toward external American or international norms.

This illustration describes an acrolectal variety of Philippine English spoken in Metro Manila, which is a historically Tagalog-speaking region. The data were elicited from four participants at an elite private university during April 2016: Speaker 1 (male, age 22 years, student), Speaker 2 (male, 18, student), Speaker 3 (female, 18, student), and Speaker 4 (female, 59, administrator).Footnote 1 A larger sample of 18 students and staff members from different parts of the Philippines were recorded during the same period, but the illustration focuses on these four speakers in particular because of their shared regional and linguistic background. They were each born and raised in Metro Manila and are fluent in the local variety of Tagalog/Filipino, but they grew up using English both at home and throughout their education in private schools.

The phonological features of this Manila variety are close to Tayao's (Reference Tayao and Lourdes2004, Reference Tayao, Lourdes, Lourdes, Bautista and Bolton2008) description of acrolectal Philippine English, and the speakers also fit Martin's (Reference Martin2014b) social profile of the Inner Circle. During interviews, they described themselves as more comfortable with English than with Tagalog or Filipino. They recognized Philippine English as a legitimate variety that is easily understood internationally but is distinctly Filipino. Only one speaker, the eldest, expressed an opinion that English teaching in the Philippines should target American norms. While the phoneme inventory of this variety is basically identical to American English, it has distinct phonetic features developed at least partly through influence from the substrate Tagalog, as the examples in this paper show.

Three types of reading tasks were used to elicit the data for this illustration: a word list, a sentence frame task, and the reading passage ‘The North Wind and the Sun’. The word list consisted of 217 words presented individually on PowerPoint slides, with each word repeated twice (n = 434). Of these 217 words, 136 were used to target minimal or near minimal consonant pairs demonstrating major phonological contrasts (e.g. voiced vs. voiceless stops), including contrasts that have previously been shown to exist in acrolectal Philippine English, but that are less common in the mesolect or basilect (e.g. /f/ as distinct from /p/; Llamzon Reference Llamzon, Lourdes and Bautista1997; Tayao Reference Tayao and Lourdes2004, Reference Tayao, Lourdes, Lourdes, Bautista and Bolton2008). The target words also included examples of phonemes in both word-initial and word-final position, and occasionally in intervocalic position, although the majority of the words had a simple monosyllabic CV or CVC structure. The remaining words in the list were mainly used to elicit examples of more complex syllable structures, showing how consonant clusters are produced in onset or coda position.

The sentence frame task was used to elicit 15 target vowels: the monophthongs /i ɪ e ɛ æ ɑ ɔ ɝ ʌ o ʊ u/ in a /bVC/ context, and the diphthongs /aɪ aʊ ɔɪ/ in a /bV/ context. These vowels have previously been identified as contrastive in Philippine English (Pillai et al. Reference Pillai, Manueli and Dumanig2010), especially in the acrolect (Tayao Reference Tayao and Lourdes2004, Reference Tayao, Lourdes, Lourdes, Bautista and Bolton2008). The target words were each elicited three times in two sentence frames (please say X and please say X again) per speaker (n = 360), and the sentences were presented to the participants on PowerPoint slides in mixed order.

Finally, the reading passage ‘The North Wind and the Sun’ was used to produce the transcriptions presented at the end of this illustration. All recordings were made a using cardioid Shure SM10A head-mounted microphone with a Zoom H2 digital recorder at a 44.1 kHz sampling rate.

Consonants

There are 24 distinct consonant phonemes in this variety of Philippine English. This inventory is similar to that of the acrolectal variety described by Tayao (Reference Tayao and Lourdes2004, Reference Tayao, Lourdes, Lourdes, Bautista and Bolton2008). As she observed (Tayao Reference Tayao, Lourdes, Lourdes, Bautista and Bolton2008: 172), the acrolect and mesolect both have consonant inventories similar to that of American English.

In onset position, the voiced stops /b d ɡ/ are consistently prevoiced, and the voiceless stops /p t k/ are often aspirated to varying degrees. These observations are supported by an analysis of the initial stops produced by each of the four speakers in the word list, as summarized in Table 1. The table lists the mean voice onset time (VOT) for tokens of initial /b/ (n = 88), /d/ (n = 48), /ɡ/ (n = 48), /p/ (n = 56), /t/ (n = 64), and /k/ (n = 48) from monosyllabic words with CV or CVC structure. The VOT was measured in Praat (Boersma & Weenink Reference Boersma and Weenink2015) from the beginning of the stop release to the onset of periodicity in the waveform.

Table 1 Mean VOT (ms) for word-initial stops produced by each of the four speakers in the word list (n = 352).

The prevoicing of /b d ɡ/ has also been documented in Tagalog (Kang, George & Soo Reference Kang, George and Soo2016). In contrast, English /b d ɡ/ are generally described as having a short lag in voicing, although prevoiced variants can also occur (Docherty Reference Docherty1992), and in some dialects they are actually more common (Hunnicutt & Morris Reference Hunnicutt and Morris2016).

According to Tayao (Reference Tayao, Lourdes, Lourdes, Bautista and Bolton2008: 162), Philippine English /p t k/ are unaspirated in the basilect and mesolect, and they are aspirated in the acrolect only rarely. They are similarly unaspirated in the substrate Tagalog (Schachter & Otanes Reference Schachter and Otanes1972, Kang et al. Reference Kang, George and Soo2016). However, Table 1 shows that the four speakers in this sample do often aspirate voiceless stops, although there is some variation between them. Speakers 3 and 4 tended to aspirate /p/ only slightly if at all, with a mean VOT of only 25 ms, and Speaker 4 also had a less aspirated /t/ compared to the other speakers. In contrast, Speakers 1 and 2 both had a mean VOT of over 50 ms for /p/, similar to their values for /t/. For all speakers, /k/ had the longest voicing lag, although the differences from the other voiceless stops were not as large for Speaker 3. The tendencies for /p/ to have a shorter VOT and for /k/ to have a longer one are common in English dialects and across languages more generally (Lisker & Abramson Reference Lisker and Abramson1964, Docherty Reference Docherty1992).

Examples further illustrating the stop voicing contrast are shown in Figure 1. The aspirated /t/ in tie has a VOT of 57 ms, and for the prevoiced /d/ in die it is –70 ms.

Figure 1 Voicing contrast between the aspirated /t/ in tie (left) and the prevoiced /d/ in die (right, Speaker 3).

In coda position, the voiced and voiceless stops tended to remain distinct in the word list task and reading passage (e.g. rip–rib, wrote–rode, and pick–pig, with no devoicing of /b/, /d/, or /ɡ/). Coda voiceless stops were usually released (likely due in part to the formal nature of the elicitation tasks), but they were also sometimes unreleased, especially by Speakers 1 and 3. In addition, Speaker 3 occasionally glottalized final /t/ (e.g. kite); it remains to be seen whether this feature is common in acrolectal Philippine English more generally.

In intervocalic position, /d/ and /t/ are usually not flapped when preceded by a stressed syllable (e.g. as in pedal and petal), as they are in American English. However, Speaker 3 occasionally produced tokens that were flapped or had incomplete closure (e.g. rider, disputing).

The English affricates and fricatives /tʃ dʒ f v θ ð z ʃ ʒ/ do not occur in Tagalog (or in many other Philippine languages) except in loanwords (Schachter & Otanes Reference Schachter and Otanes1972: 18; McFarland Reference McFarland, Lourdes, Bautista, Llamzon and Sibayan2000), although [tʃ] and [dʒ] exist as allophones of /t/ and /d/ before a high front vowel. Thus, for basilectal or mesolectal Philippine English speakers, there can be L1 influence in the pronunciation of these consonants, and in some cases, they are merged with other phonemes (Tayao Reference Tayao, Lourdes, Lourdes, Bautista and Bolton2008: 172). For example, Tayao (Reference Tayao, Lourdes, Lourdes, Bautista and Bolton2008: 162) reported that basilectal speakers pronounce /tʃ/ as [ts] and /dʒ/ as [dj] word-initially or [ds] word-finally. The substitution of [p] for /f/ is also a common stereotype of Philippine English, as is the hypercorrection of /p/ to [f] (e.g. pay [feɪ]; Hiramoto Reference Hiramoto2011: 352–354). However, Tayao (Reference Tayao, Lourdes, Lourdes, Bautista and Bolton2008: 162) described the acrolect as maintaining distinction for all of these phonemes, although /θ/ and /ð/ are sometimes stopped to [t] and [d]. In general, these observations hold true for the acrolectal speakers in this sample. They consistently distinguished between /p/ and /f/ (e.g. pine, fine), and they did not hypercorrect /p/ to [f] during any of the tasks or in interview speech. In addition, /v/ remains distinct from /b/ (e.g. vote, boat), unlike in the basilect (Tayao Reference Tayao, Lourdes, Lourdes, Bautista and Bolton2008: 162).

There is some variation in the production of /θ/ and /ð/. Speakers 1 and 4 consistently produced them as [θ] and [ð] in both the word list and reading task. Figure 2 shows examples of how Speaker 1 produced /θ/ as a fricative in onset (thin) and in coda position (booth) in the word list.

Figure 2 The production of /θ/ in onset in thin (left) and in coda in booth (right) by Speaker 1.

Speaker 3 also consistently produced the interdental fricatives as [θ] and [ð] in her word list. However, in the reading passage, word-initial and word-medial, intervocalic /ð/ were sometimes partially or completely stopped to [d], with audible stop bursts, although final /θ/ generally remained [θ], as shown in Figure 3.Footnote 2

Figure 3 The production of word-initial /ð/ (the) and word-final /θ/ (north) by Speaker 3, extracted from the larger phrase and so the north wind was obliged.

In contrast, Speaker 2 produced fricative and stop variants in both tasks. Occasionally, his fricative variants were assibilated (e.g. thin [sɪn]), or, in coda position, produced as a stop followed by an interdental fricative or a sibilant (e.g. booth [butθ] or [buts]). These examples are shown in Figure 4. More data is needed to show whether this assibilation is common among other speakers of this variety or if this is an idiosyncratic feature. In stereotypical performances of Philippine English, [t] and [d] are the only nonstandard forms used for /θ/ and /ð/ (Hiramoto Reference Hiramoto2011: 352–353). Such substitutions are common in other varieties of English, including neighboring Asian varieties (Baskaran Reference Baskaran2008, Wee Reference Wee2008) and some dialects of American English.

Figure 4 Assibilated variants of /θ/ in onset (thin, left) and in coda (booth, right) as produced by Speaker 2.

The sibilant phonemes /s z ʃ ʒ/ are generally distinct for the speakers in this sample. Three of the four speakers pronounced both hiss /hɪs/ and his /hɪz/as [hɪs] in the word list, suggesting that /s/ and /z/ may sometimes neutralize in coda position. However, they all distinguished bus [bʌs] from buzz [bʌz]. Most of the speakers also distinguished between /ʃ/ and /ʒ/ (e.g. washer and measure), but Speaker 2 produced them both as [ʃ].

Most Southeast Asian Englishes are described as non-rhotic, although rhoticity may be emerging in some varieties due to local substrate effects or recent influence from the American media (Salbrina & Deterding Reference Salbrina and Deterding2010, Tan Reference Tan2012). Philippine English has had American rather than British influence from the beginning, however, so it is highly rhotic in comparison. According to Tayao (Reference Tayao, Lourdes, Lourdes, Bautista and Bolton2008: 162), the rhotic in the acrolect is quite similar to the approximant /ɹ/ of American English, although it is often tapped or trilled in the basilect or mesolect due to L1 influence. In fact, the approximant seems to be spreading across sociolects and even influencing other Philippine languages; for example, its use seems to be widespread in the different varieties of English or Taglish (Tagalog–English codeswitching) used on television, and Lesho (Reference Lesho2013) has found that it has become common in Cavite Chabacano (a Tagalog–Spanish creole), especially in coda position and among female speakers.

In this Philippine English sample, all speakers used an approximant /ɹ/ across different phonological environments. In the word list, [ɹ] occurred in simple or complex onsets (rock, arrive, pray) and post-vocalically before a consonant or pause (portion, fare). In addition, [ɝ] appeared in words belonging to the nurse set (word) and in unstressed final syllables (dipper). There were no instances of /ɹ/ being trilled or tapped in any of the tasks, with three near exceptions. In one token of strengths (Speaker 2) and two of threw (Speaker 4), an epenthetic vowel was inserted before the rhotic, which was then partially tapped.

Figure 5 shows word list examples of /ɹ/ in onset (rib) and coda position (fear); in both cases, there is no closure, and the F3 is quite low and close to the F2. The downward F3 trajectory for the rhotic in fear also begins quite early during the preceding /i/. It is often difficult to draw a reliable boundary, as r-coloring often extends throughout the preceding vowel (see also north in Figure 3 above).

Figure 5 Examples of /ɹ/ in onset (rib, left) and coda (fear, right) as produced by Speaker 3 in the word list.

The speakers were also consistently rhotic during the reading passage. They produced [ɹ] or [ɝ] in every possible post-vocalic context before a consonant or pause (e.g. hard [ˈhɑɹd], stronger [ˈstɹɔŋɡɝ]).

The pronunciation of /l/ differs depending on syllable position, as in American English. Each of the speakers in this sample produced a lighter /l/ in onset, as in leaf, and a darker /l/ in coda, as in feel. These examples are shown in Figure 6, with the formant tracks for /l/ highlighted to make the faint F2 in the leaf example more visible. The /l/ in feel is velarized, as indicated by the substantially lower F2 compared to that of the /l/ in leaf. Tagalog, in contrast, has only the light /l/ (Schachter & Otanes Reference Schachter and Otanes1972: 24).

Figure 6 Dark /l/ in coda position (feel, left) and light /l/ in onset (leaf, right), as produced by Speaker 3.

The distribution and production of /h/, the nasals (/m n ŋ/), and glides (/w j/) do not have any notable Tagalog influence or differences from American English.

Vowels

The diagrams above show the monophthongs and diphthongs that are distinguished by these Philippine English speakers, and the accompanying list shows the 15 target words that were used in the sentence reading task.Footnote 3 The monophthong chart is adapted from Tayao (Reference Tayao and Lourdes2004, Reference Tayao, Lourdes, Lourdes, Bautista and Bolton2008), who in turn based her choice of vowel symbols on comparison to American English. Acoustic evidence supports the classification of /e/ and /o/ here as monophthongs, rather than as the diphthongs /eɪ/ and /oʊ/, as later discussion in this section will show.

As Tayao (Reference Tayao, Lourdes, Lourdes, Bautista and Bolton2008: 163, 173) noted, the vowel inventory of acrolectal Philippine English is nearly identical to that of American English, although she considered /æ/ to have a marginal status because it was often merged with /ɑ/ in her sample. The mesolect and basilect tend to merge tense and lax vowel pairs and lack /æ/ and/or /ʌ/, as Philippine languages like Tagalog and Cebuano do not make these distinctions (Tayao Reference Tayao, Lourdes, Lourdes, Bautista and Bolton2008: 163, 173). In the acoustic analysis by Pillai et al. (Reference Pillai, Manueli and Dumanig2010), the sociolinguistic background of the speakers was unclear, but their findings closely matched Tayao's (Reference Tayao and Lourdes2004, Reference Tayao, Lourdes, Lourdes, Bautista and Bolton2008) acrolectal description. They found that /æ/ and /ʌ/ were distinct from neighboring vowels and that the tense–lax distinctions were mostly maintained, although the differences between the mean F1 and F2 values for /i/ and /ɪ/ were small, suggesting that the contrast in quality was not always clear (Pillai et al. Reference Pillai, Manueli and Dumanig2010: 90).

The monophthongal vowel spaces of the four speakers in this sample are shown in Figure 7, which is based on the results of the sentence reading task. The vowel category means presented in this graph include tokens from both sentence frame types, please say X and please say X again (n = 288).

Figure 7 Monophthongal vowel category means at the vowel midpoint by gender for the four speakers (n = 288). The formant values have been converted to a Bark scale (Traunmüller Reference Traunmüller1990).

The results in Figure 7 show that the tense–lax pairs /i/–/ɪ/, /e/–/ɛ/, and /u/–/ʊ/ have clearly distinct formant patterns. Similar to the findings by Pillai et al. (Reference Pillai, Manueli and Dumanig2010), the speakers all produced /æ/ as quite distinct from both /ɑ/ and /ɛ/, and /ʌ/ was also distinguished from surrounding vowels. There is perhaps some variation in the production of the /ɑ/ in bot. The two male speakers merged it completely with the /ɔ/ in bought, producing both in a mid and back position. However, while there was some overlap for the female speakers, /ɑ/ was slightly more low and front than /ɔ/, especially for Speaker 4. In the description by Pillai et al. (Reference Pillai, Manueli and Dumanig2010: 92), /ɑ/ was similarly lower and more front in the vowel space, contrasting clearly with /ɔ/.

Some vowel pairs were distinguished not only through quality but also to some extent through duration, as the data in Table 2 suggest. In general, tense vowels were longer for the /i/–/ɪ/, /e/–/ɛ/, and /u/–/ʊ/ pairs, although in some cases the differences were small (Speaker 3’s /i/–/ɪ/ and /e/–/ɛ/, and Speaker 4’s /e/–/ɛ/). These patterns differ slightly from Cruz's (Reference Cruz2015: 96–97) finding that among a small sample of Filipino college students, English /i/–/ɪ/ and /e/–/ɛ/ were generally distinct, but duration differences between /u/ and /ʊ/ were quite small, with some participants actually having a slightly longer /ʊ/. In this sample, the /u/–/ʊ/ pair was much more distinct.

Table 2 Duration ratios of spectrally similar vowel pairs for each of the four speakers (n = 192).

In addition to these three tense–lax pairs, Table 2 lists duration ratios for other vowel pairs that were shown to be spectrally similar in Figure 7, or that have been previously described as such in Philippine or American English (Hillenbrand et al. Reference Hillenbrand, Getty, Clark and Wheeler1995; Hillenbrand Reference Hillenbrand2003; Tayao Reference Tayao and Lourdes2004, Reference Tayao, Lourdes, Lourdes, Bautista and Bolton2008). The table shows that the speakers’ /ɔ/ and /ɑ/ vowels are highly similar not only spectrally but also temporally. The duration differences between /æ/ and /ɑ/ were also relatively small, but the temporal distinction is perhaps not very important for this pair, since although Tayao (Reference Tayao and Lourdes2004, Reference Tayao, Lourdes, Lourdes, Bautista and Bolton2008) described them as partially merged, their F1 and F2 values are quite different in this sample. The duration differences seem to be largest for the /o/–/ʊ/ and /u/–/ʊ/ pairs. These three vowels were clustered quite closely together in the vowel space (see Figure 7).

Figure 8 shows the average spectral movement of the diphthongs /aɪ aʊ ɔɪ/ for the four speakers by gender, based on results from the same sentence reading task. The vowels /e/ and /o/ are also included in order to assess whether they are diphthongal, as in many dialects of American English (e.g. Hillenbrand Reference Hillenbrand2003, Fox & Jacewicz Reference Fox and Jacewicz2009). The vowels were measured at the 20% and 80% points of the vowel duration (n = 120), indicated in Figure 8 by the tails and heads of the arrows, respectively.

Figure 8 Diphthongal vowel category means at the 20% and 80% points by gender, including means for /e/ and /o/ (n = 120). The formant values have been converted to a Bark scale (Traunmüller Reference Traunmüller1990).

The characteristics of Philippine English diphthongs have not been described in any previous studies. For these four speakers, Figure 8 below shows that the nuclei of /aɪ/ and /aʊ/ are in a low central position, and they are fully diphthongized, with both offglides approaching the periphery of the high mid part of the vowel space. The nucleus of /ɔɪ/ has a mid back position, and the offglide approaches /e/. The mid vowels /e/ and /o/ exhibit relatively little spectral change from the 20% to the 80% points, and so they may be classified as monophthongs. For /e/, all speakers had a slight offglide in the direction of /i/. However, there was some variation in the spectral movement of /o/. For both of the male speakers, the offglide moved slightly toward /u/, but for the two female speakers, it was slightly centralized.

Prosody

Syllable structure in acrolectal Philippine English is similar to that of other standard English varieties. In onset position, clusters of two or three consonants are permitted (e.g. play, bright, queen, street, splash, etc.). No epenthetic vowel is inserted before clusters beginning with /s/ (e.g. screw [skɹu] rather than [ɪskɹu]), as often occurs in the mesolect and basilect (Tayao Reference Tayao and Lourdes2004: 84). In this sample, as previously described, epenthesis occurred only in a few instances before /ɹ/ in the words threw and strengths. Consonant clusters are also permitted in coda position (e.g. rinse, rubs, cold, prompt, etc.); however, final stops in coda clusters are sometimes deleted (Tayao Reference Tayao, Lourdes, Lourdes, Bautista and Bolton2008: 162), especially /t/. For example, in the word list, Speaker 3 omitted the final /t/ in gift [ɡɪf], searched [sɝtʃ], and tempt [tɛmp]. According to Tayao (Reference Tayao and Lourdes2004, Reference Tayao, Lourdes, Lourdes, Bautista and Bolton2008), this consonant cluster reduction occurs more frequently in mesolectal and basilectal varieties. Similarly, she noted that the mesolect and basilect have a greater tendency than the acrolect to insert full vowels before syllabic /l/ and /n/ (e.g. little [ˈlɪtɛl] instead of [ˈlɪtl̩] or garden [ɡɑɹdɛn] instead of [ɡɑɹdn̩]; Tayao Reference Tayao, Lourdes, Lourdes, Bautista and Bolton2008: 162). In the word list for this sample, the four speakers tended to produce syllabic /l/ (e.g. little [lɪtl̩]), but they often had a full vowel before /n/ (e.g. lesson [ˈlɛsʌn] and kitten [ˈkɪtɛn]).

Like both American English and Tagalog, Philippine English has lexical stress. In Tayao's (Reference Tayao and Lourdes2004, Reference Tayao, Lourdes, Lourdes, Bautista and Bolton2008) descriptions, she observed that stress in the acrolect mostly follows the same patterns as in American English, although she identified a few words that differ in syllable placement (e.g. colleague [kɑˈliɡ] instead of [ˈkɑliɡ]; Tayao Reference Tayao, Lourdes, Lourdes, Bautista and Bolton2008: 85). She also noted that acrolectal speakers tend to reduce unstressed vowels to [ə] or [ɪ], whereas mesolectal and basilectal speakers produce full vowels. However, there has not yet been any phonetic research on stress in Philippine English, so it is not yet known what its specific acoustic correlates might be, or to what extent unstressed vowel reduction takes place. The present data do not allow for a detailed phonetic analysis of how stress is marked in this variety, as most of the target words in the word list task were monosyllabic. However, some preliminary observations about unstressed vowel reduction can be made based on examples from the reading passage.

There are unstressed vowel reduction patterns in the reading passage that suggest some similarities to other Southeast Asian Englishes (Deterding Reference Deterding2010: 369–370). For example, all speakers except Speaker 1 pronounced confess as [konˈfɛs], with a full vowel in the unstressed syllable instead of reducing it to [ə]. Similarly, in the phrase was obliged, three of the four speakers produced oblidged as [oˈblaɪdʒ]; Speaker 4, however, had an initial vowel similar to the one in was [wəs]. All except Speaker 2 also had a fairly unreduced vowel in the first syllable of succeeded, although the final vowel tended to be reduced (e.g. [sʌkˈsidɪd] or [sʌkˈsidəd]). However, words like along consistently had a reduced [ə] in the first syllable. These patterns suggest some similarity to previous findings that in Singapore English and other neighboring varieties, the initial vowels in polysyllabic words tend to stay unreduced when they are in closed syllables, particularly when they are spelled with <o>, whereas the <a> spelling and open syllables tend to favor reduction (Deterding Reference Deterding2010: 369–370; Deterding & Salbrina Reference Deterding and Sharbawi2013: 28–29).

Another feature common in Southeast Asian Englishes is the relative lack of reduction in monosyllabic function words such as that, than, and of in comparison to British or American English (Deterding Reference Deterding2010, Deterding & Salbrina Reference Deterding and Sharbawi2013). In this sample, full vowels often occurred in such contexts. For example, in the phrase blew as hard as he could, all speakers except Speaker 4 had a full [æs] in the first instance of as, with only a slight vowel reduction (if any) in the second instance. Similarly, in the phrase and at last, Speaker 1 had an [æ] in all three words, although the other speakers had slightly more reduced vowels in and and at (e.g. [ɛnd], [ɛt]). However, in the phrase stronger of the two, the vowel in of was usually [ə], except in the case of Speaker 2, whose pronunciation was closer to [ɔf].

Tayao (Reference Tayao and Lourdes2004, Reference Tayao, Lourdes, Lourdes, Bautista and Bolton2008) described some basic features of phrase-level prosody in Philippine English, claiming that the acrolectal variety is generally similar to American English. For example, she described a few general intonation patterns used in various contexts (e.g. a rising contour for vocatives and different question types; Tayao Reference Tayao, Lourdes, Lourdes, Bautista and Bolton2008: 167). However, more detailed studies of Philippine English phrasing, intonation, and rhythm are still needed.

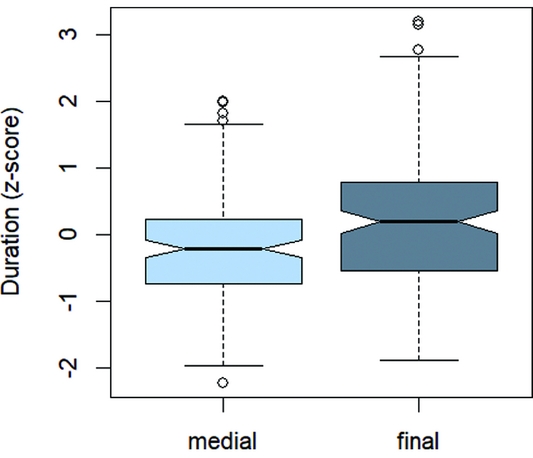

The present data allow for some preliminary observations about how Philippine English marks phrasal boundaries through cues such as vowel duration or quality. In Tagalog, the right edge of the phrase is marked with lower vowel quality, longer vowel duration, and a wider pitch range (Gonzalez Reference Gonzalez1970, Anderson Reference Anderson2006). Lesho (Reference Lesho2013) found that as a result of Tagalog substrate influence, Cavite Chabacano also has longer vowel duration in phrase-final than in non-final position, as well as greater vowel dispersion. In this sample, there is evidence that Philippine English may have similar phrase-final lengthening, as shown in Figure 9 above. These data come from the sentence reading task, including the same set of monophthongal vowels plotted in Figure 7. The duration measurements were z-scored in order to account for inherent vowel and speaker differences, and the results are split into phrase-final (please say X) and phrase-medial contexts (please say X again). As the figure shows, the speakers had a tendency to lengthen phrase-final vowels.

Figure 9 Normalized monophthongal vowel duration in phrase-medial (please say X again) and phrase-final contexts (please say X) across the four speakers (n = 288).

Based on the same data, Figure 10 below compares the quality of monophthongal vowels in each phrasal context for the two male and two female speakers. The results show that the men had little difference in vowel quality between phrase-final and phrase-medial syllables. However, the women had lower vowels in phrase-final position. With the exception of /u/, which was more back, their phrase-final vowels were also more front. The difference in mean F2 values was especially pronounced for the front vowels.

Figure 10 Monophthongal vowel category means at the vowel midpoint by gender and phrasal position (n = 288). The formant values have been converted to a Bark scale (Traunmüller Reference Traunmüller1990).

This difference in vowel quality for female speakers in phrase-final position, along with the longer vowel duration for both groups, suggests some possible similarities to how phrase boundaries are marked in Tagalog (Gonzalez Reference Gonzalez1970).

Transcriptions of the recorded passage

The following transcriptions represent the speech of Speaker 1.

Orthographic

The North Wind and the Sun were disputing which was the stronger, when a traveler came along wrapped in a warm cloak. They agreed that the one who first succeeded in making the traveler take his cloak off should be considered stronger than the other. Then the North Wind blew as hard as he could, but the more he blew the more closely did the traveler fold his cloak around him, and at last the North Wind gave up the attempt. Then the Sun shined out warmly, and immediately the traveler took off his cloak. And so the North Wind was obliged to confess that the Sun was the stronger of the two.

Broad

ðə ˈnoɹθ ˈwɪnd ænd ðə ˈsʌn wɝ dɪsˈpjutɪŋ wɪtʃ wəz ðə ˈstɹɔŋɡɝ, wɛn ə ˈtɹævəlɝ kem əˈlɔŋ ˈɹæpt ɪn ə ˈwɑɹm ˈklok. ðe əˈɡɹid ðæt ðə ˈwʌn hu ˈfɝst səkˈsidəd ɪn ˈmekɪŋ ðə ˈtɹævəlɝ ˈtek hɪz ˈklok ɔf ʃʊd bi kənˈsɪdɝd ˈstɹɔŋɡɝ ðɛn ði ˈʌðɝ. ˈðɛn ðə ˈnoɹθ ˈwɪnd ˈblu æz ˈhɑɹd æz hi ˈkʊd, bət ðə ˈmoɹ hi ˈblu, ðə moɹ ˈklosli dɪd ðə ˈtɹævlɝ ˈfold hɪz ˈklok əˈɹaʊnd hɪm, ænd æt ˈlæst ðə ˈnoɹθ ˈwɪnd gev ˈʌp ði əˈtɛmpt. ˈðɛn ðə ˈsʌn ˈʃaɪnd aʊt ˈwɑɹmli, ænd ɪˈmidjətli ðə ˈtɹævəlɝ tʊk ˈɔf hiz ˈklok. ænd so ðə ˈnoɹθ ˈwɪnd wəz əˈblaɪdʒd tu kənˈfɛs ðɛt ðə ˈsʌn wəz ðə ˈstɹɔŋɡɝ əv ðə ˈtu.

Narrow

ðə ˈnoɹθ ˈwɪnd ɛn ðəˈsʌn wɝ dɪsˈpʉtɪŋ wɪtʃ wəs ðə ˈstɹɔŋɡɝ, ˈwɛn ə ˈtʃɹævəlɝ ˈkʰem əˈlɔŋ ˈɹæpt ɪn ə ˈwɑɹm ˈkʰlok. ðe ˈɡrid ðæ ðə ˈwʌn ɦu fɝ sʌkˈsidəd ɪn ˈmekɪŋ ðə ˈtʃɹævəlɝ ˈtʰekʰ ɪs ˈkʰlok ɔf ʃʊd bi kənˈsɪdɝd ˈstɹɔŋɡɝ ðɛn ði ˈʌðɝ. ðɛn ðə ˈnoɹθ ˈwɪn ˈblu æs ˈhɑɹd æs hi ˈkʊd, bəd ðə ˈmoɹ hi blu, ðə ˈmoɹ ˈkʰlosli dɪ ðə ˈtɹævlɝ ˈfold ɪs ˈkʰlok əˈɹaʊnd hɪm, ænd æt ˈlæs ðə ˈnoɹθ ˈwɪn ɡev ˈʌp ði əˈtɛmpt. ðɛn ðə ˈsʌn ˈʃaɪnd aʊʔ ˈwɑɹmli, ænd ɪˈmidjɛtli ðə ˈtɹævəlɝ tʊk ˈɔf is ˈkʰlok. ɛnd so ðə ˈnoɹθ ˈwɪnd wəz oˈblaɪdʒ tə kənˈfɛs ðət θə ˈsʌn wəs ˈstɹɔŋɝ əv ðə ˈtʰu.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the Institute of Philippine Culture at the Ateneo de Manila University for hosting me as a Visiting Research Associate during the collection of this data, and Eeva Sippola for providing project funds through the Postcolonial Language Studies research group at the University of Bremen. Thanks also go to Michael Coroza, Jason Jacobo, and Michael de Matto for additional assistance with the project, and to Amalia Arvaniti and the two reviewers for their help in improving this paper. Finally, I am grateful to the participants for lending their voices to this study.