Impact statement

This study contributes to a deeper understanding of the impacts of plastic pollution in West Africa, and particularly Ghana. The impacts highlighted in this article provide a macro perspective to the consequences of the pollution, yet providing a nuanced outline of both high- and low-level impacts of plastic pollution in the country. The findings from this study can inform pertinent policies, tailored to mitigate plastic pollution in Ghana. Thus, it is expected that the study contributes significantly to the promotion of ecological and socioeconomic practices in the country, region and beyond.

Introduction

Over the past few decades, plastics have been utilised across various sectors for different applications. Attributes such as high strength-to-weight ratio, flexibility and versatility, varied types for different applications, providing barriers to moisture or microbial activity, recyclability, low cost, transparency, insulation and durability have all contributed to swift and widespread adoption of plastics in almost all sectors (Marsh and Bugusu, Reference Marsh and Bugusu2007). However, plastic pollution and the accumulation of plastic waste in recent years have led to serious concerns about the consequences of its unsustainable production, use and the management of its waste. Concerning reports on the increasing quantities of plastic entering the oceans, accumulation of plastic waste on land and the negative impacts of microplastics on marine life and human beings highlight the global nature of the plastic problem (Galloway et al., Reference Galloway, Cole and Lewis2017; Neilson, Reference Neilson2018). Plastic pollution has a significantly negative global impact, and therefore finding a solution to prevent, or mitigate the pollution requires collaboration and joined-up thinking within countries, as well as at the international level. Approaches to addressing the problem often tend to focus on reducing plastic use or increasing the levels of appropriate disposal. However, the unavailability of appropriate methods of treatment, management and disposal remain the key challenges, particularly for low- and middle-income countries. For instance, while high-income countries have legal frameworks to regulate how pellets are produced, transported and used to reduce plastic pollution, the legal frameworks in low- and middle-income countries are not sufficiently designed to reduce industrial pellet spills (Alpizar et al., Reference Alpizar, Carlsson, Lanza, Carney, Daniels, Jaime and Ho2020). This is often the case in the Western African context where the dominant policy approach is to ban single-use plastic products (SUPPs). Despite adopting some of the harshest punitive antiplastic bans (Adam et al., Reference Adam, Walker, Bezerra and Clayton2020), SUPP continues to be ubiquitous in the Western Africa, with marine and land pollution continuing to be commonplace.

Overall, the low cost, lack of regulation or control in some low- and middle-income countries have led to the widespread production of SUPPs, resulting in significant accumulated plastic waste (Alpizar et al., Reference Alpizar, Carlsson, Lanza, Carney, Daniels, Jaime and Ho2020). In addition, in several countries, the lack of robust infrastructure to collect, recycle, remanufacture or repurpose the plastic waste has exacerbated the situation and has resulted in various negative social, ecological and economic impacts. Furthermore, evidence from the literature suggests that policy approaches to target reduction and appropriate collection of plastics in the West African region have not been successful for several reasons, including lack of policy and limited consultation with stakeholders during policy design (Adam et al., Reference Adam, Walker, Bezerra and Clayton2020), pro plastic use attitudes among individuals, and lack of a detailed understanding of individual and non-personal factors that favour SUPPs (Adam et al., Reference Adam, Walker, Clayton and Bezerra2021). Therefore, to effectively address plastic pollution in the West African region, a detailed understanding of the aspects that shape the reduction of plastic waste and appropriate waste collection strategies is warranted.

The parameters shaping the nature and scale of the plastic problem in both high- and low-income country contexts are well-known and documented in the literature. However, the ineffectiveness of policy approaches, aimed at the reduction and appropriate collection of waste, necessitates novel approaches to a deeper-level understanding of the said parameters. Correspondingly, this study adopts a system thinking approach to explore the negative social, ecological and economic impacts of plastic pollution in Ghana as a low–middle-income country. The study is exploratory and intends to pool useful contextual insights for Ghana, which can inform pertinent interventions or policy development. Accordingly, the study contributes to the academic literature, whereby a more comprehensive assessment of plastic pollution at macro level is provided for Ghana. First, the findings of the study, derived from the application of system dynamics methodology, provide a holistic picture of the macro impacts of plastics pollution in Ghana. Second, the findings, in turn, provide a basis for pertinent recommendations that can be found useful by the policymakers, and the general population.

The study is structured as follows: Section ‘Background’ provides a background to types of plastic waste, regulatory frameworks, waste management practices and existing infrastructure within the Ghanaian context. Section ‘Methodology’ presents the methodology. Section ‘Results’ provides the results of the study. This section outlines the social, ecological and economic impacts of plastic pollution in Ghana. In addition, it provides a holistic view of the causes of plastic pollution. Section ‘Discussion and recommendations’ includes the discussion and a set of recommendations for relevant stakeholders. The article is concluded in the Section ‘Conclusion’.

Background

Types of plastics

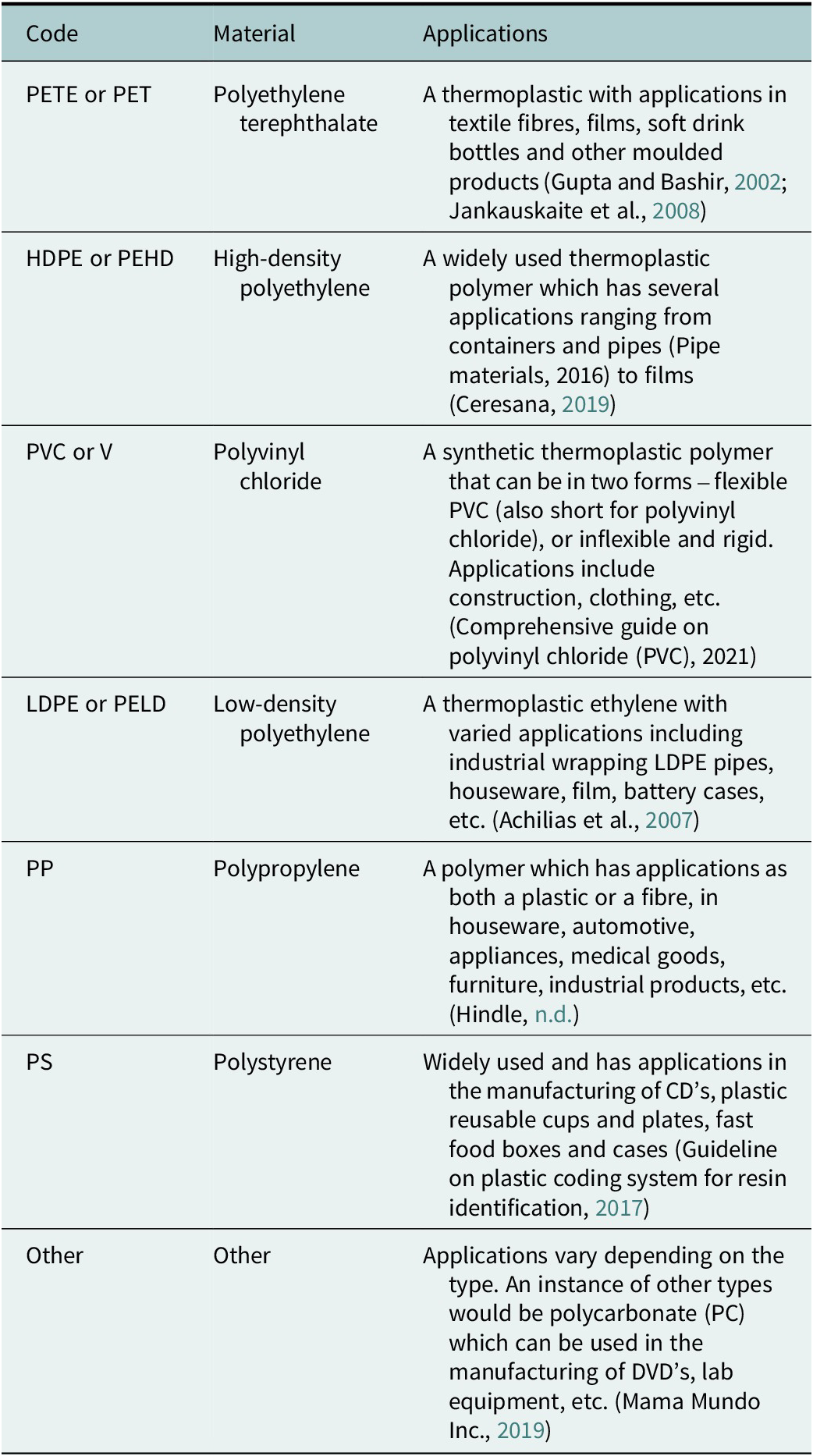

Different categorisations of plastic materials have been presented within the literature. These categorisations are typically either based on the material or the application of the finished plastic product. The Plastics Industry Association started categorising plastics since 1988, and using a set of classification codes (Codes & standards, 2024a, b). The Hong Kong Environmental Protection Department also outlined the seven-class plastic coding system (Guideline on plastic coding system for resin identification, 2017), which is based on the plastic material (Table 1).

Table 1. Plastics coding system, adapted from Guideline on plastic coding system for resin identification (2017)

As highlighted above, there are other categorisations for plastic based on the application. Accordingly, there are other instances of plastic-based products that are used in engineering applications and are not listed within the coded classification in Table 1. Engineering plastics and bioplastics are among such examples (EuRIC, n.d.).

Plastics benefits

A key argument being made in the literature is that plastic waste should be treated as a resource since a significant part of the waste is often recyclable (Oteng-Ababio, Reference Oteng-Ababio2014). Plastics offer several benefits that have led to their fast adoption by consumers. Plastics are lightweight, easy to manufacture and water-resistant (Andrady and Neal, Reference Andrady and Neal2009). The food manufacturing industry has widely espoused plastics for packaging since they offer suitable atmospheric control between the food and the ambient environment. Additionally, due to the transparent property of the plastic materials used, labels and other information indicators can be built into food packaging (Andrady and Neal, Reference Andrady and Neal2009). There have also been studies comparing plastics to other materials trying to assess the benefits that plastic may offer; in a study by Hocking (Reference Hocking1994), it was confirmed that a polystyrene cup will save energy compared to a ceramic cup when considering the energy needed for the cleaning of the ceramic cup 100 times. The high ratio of strength to weight for plastics makes them suitable products for packaging purposes compared to ceramic and glass containers (Andrady and Neal, Reference Andrady and Neal2009). Plastic packaging, which is 26% of the total volume of plastics used globally (Drzyzga and Prieto, Reference Drzyzga and Prieto2019), does not just offer economic benefits; it is also deemed to be a suitable preventative measure against food contamination if used for food packaging. Additionally, the plastic industry contributed to 1.5 million jobs and 340 billion euros in turnover as of 2017 in Europe alone (Plastics—the facts, 2019, An Analysis of European Plastics Production Demand and Waste Data 2016).

Considering the wide adoption of plastics, managing resulting plastic waste is of a great importance. Tulashie et al. (Reference Tulashie, Boadu and Dapaah2019) proposed a novel pyrolysis approach to convert mixed solid plastic into crude fuel. A study conducted on the impacts of the Dompoase landfill in Kumasi, Ghana revealed that the effects of landfill creation have had both positive and negative effects on agricultural farmers and nearby residents, respectively (Owusu-Sekyere et al., Reference Owusu-Sekyere, Osumanu and Yaro2013). Another study conducted in the city of Wa in the Upper West region in Ghana revealed that there are differences in waste management practices in cities compared to rural areas; It is argued that in rural areas, waste management infrastructure is either non-existent or is in a stale state and accordingly, community participation, investment in infrastructure and health promotion improve waste management practices and contribute to a higher level of sanitation (Amoah and Kosoe, Reference Amoah and Kosoe2014).

There have also been studies focussed on the Accra metropolitan area in Ghana. For instance, Oteng-Ababio (Reference Oteng-Ababio2011) evaluated sustainable waste management practices in the region and argued that there is a need for a focussed assessment of circular practices through the examination of waste flows and considering waste as a resource with economic value. Public–private partnerships (PPPs) are often considered an approach to raise funding for pertinent sustainability investment (Oteng-Ababio, Reference Oteng-Ababio2010). However, the lack of data to justify investment in solid waste management has been a concern and can potentially lead to ‘ill-fated’ investment strategies (Oteng-Ababio et al., Reference Oteng-Ababio, Arguello and Gabbay2013).

Recycling plastics

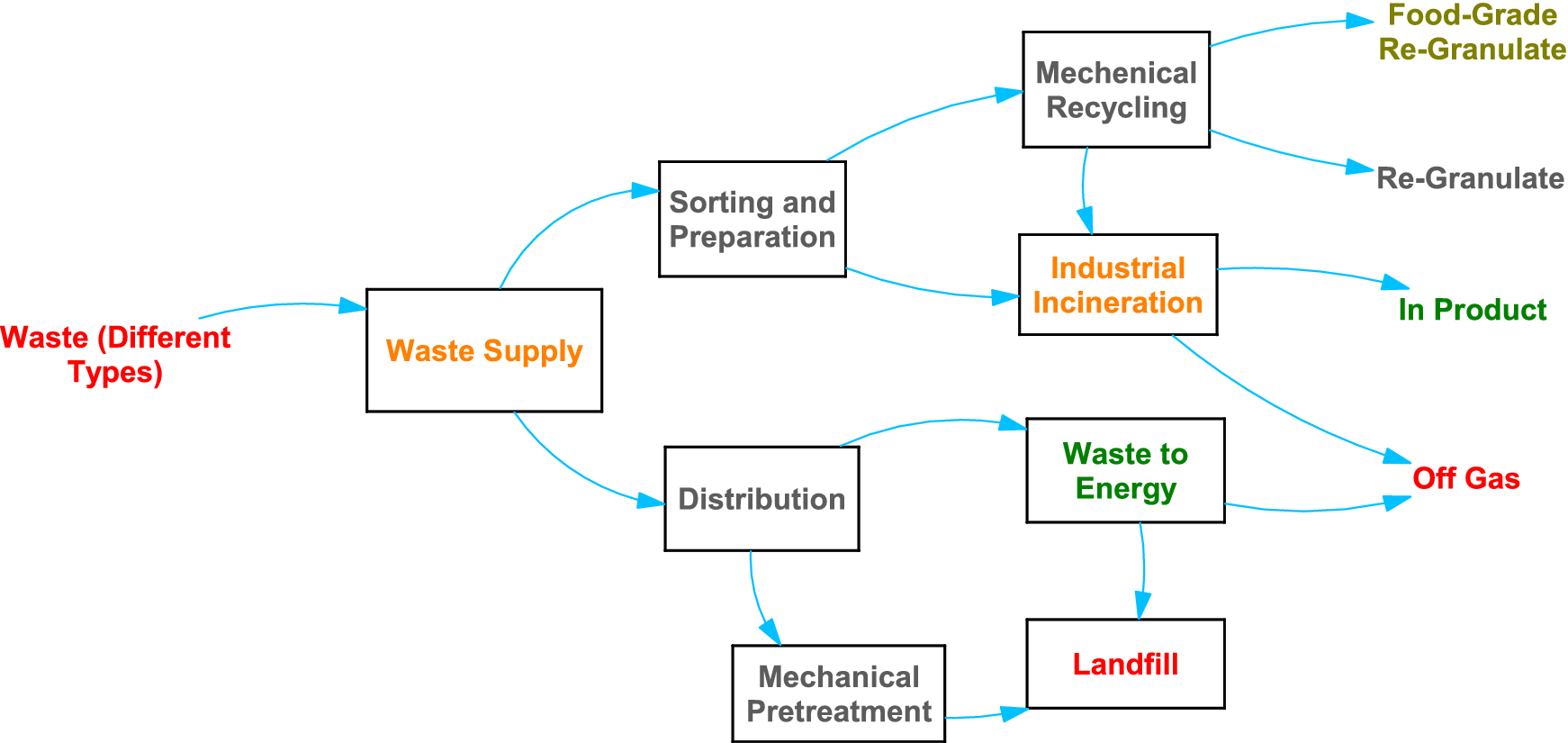

Despite the many benefits that plastics offer, they typically have a short use life, resulting in large quantities of plastic waste every year, many of which end up in water and soil, causing ensuing economic and ecological damage (Drzyzga and Prieto, Reference Drzyzga and Prieto2019). Despite the efforts by researchers, practitioners and policymakers to promote plastic recycling, there are ‘organisational’, ‘technological’ and ‘regulatory’ barriers (Milios et al., Reference Milios, Christensen, McKinnon, Christensen, Rasch and Eriksen2018). Shen and Worrell (Reference Shen and Worrell2014) report that plastic recycling following consumer use has been adopted far slower than recycling of other materials such as paper. They also outline a significant gap between plastic recovery and plastic recycling, even in countries that are advanced in waste management, resulting in plastic waste ending up in landfills (Figure 1). In many case studies, recovered plastic ends up in landfills due to the low demand for secondary plastic (Milios et al., Reference Milios, Christensen, McKinnon, Christensen, Rasch and Eriksen2018). This also leads to an accumulation of waste throughout the value chains.

Figure 1. A typical waste stream for plastic – a case study from Australia, adapted from Van Eygen et al. (Reference Van Eygen, Laner and Fellner2018).

Several studies have been undertaken on ‘closing the loop’ in plastic recycling supply chains by conducting a circularity assessment of plastics. Eriksen et al. (Reference Eriksen, Christiansen, Daugaard and Astrup2019) demonstrated the suitability of closed-loop recycling for polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and polypropylene (PP). Nonetheless, they argued that the degradability of PP during recycling is one of the key barriers to multiple closed-loop recycling cycles. Similarly, Hahladakis and Iacovidou (Reference Hahladakis and Iacovidou2018) report that the quality of the recycled material is an important factor in the success of plastic recycling.

It is argued by many authors that pertinent legislation and governance play a crucial role in speeding up endeavours for tackling plastic pollution. Several instances of policy bottlenecks are highlighted within the literature as disruptors of plastic recycling ecosystems. An instance of this is China’s National Sword policy, which bans imports of recyclable plastic packaging (Carr et al., Reference Carr, Fetherston, Meyer and Makled2019). Additionally, such policy loopholes create legal escapes that some companies can exploit to avoid their social responsibility by limiting pollutants from their operations (Hyslop et al., Reference Hyslop, Sarwar and Hosseinian-Far2023). Although the idea of closed-loop supply chains, recycling and reusing plastic products seems very plausible, there are a number of resultant issues and negative environmental impacts. Plastics degrade through recycling, and due to the incompatibility between different types of plastics, separation is needed for reprocessing (Goodship, Reference Goodship2007). Plastic recycling also entails volatile organic compound (VOC) pollution, and the amount of pollution is dependent on several factors, including the type of plastic (He et al., Reference He, Li, Chen, Huang, An and Zhang2015).

Plastics pollution and policy approach in Ghana

Plastic consumption in Ghana has increased significantly as a result of the country’s rapid development and transformation into a low–middle-income economy over the last three decades (Asare et al., Reference Asare, Kuranchie, Ofosu and Verones2019). Each year, Ghana produces 840,000 tonnes of plastic waste, however, only 9.5% of it is collected for recycling (WEF, 2023). However, the absence of adequate waste management means that most plastics end up in landfills or in drainage systems that leak into the Atlantic Ocean. Perennially, coastal cities such as Accra and Cape Coast experience flooding due to the choking of waterways and storm-water drains caused by plastic waste (Adam et al., Reference Adam, Walker, Bezerra and Clayton2020). The environmental effects of this lack of robust plastic waste management infrastructure often manifest in damage to marine life, and the pollution of freshwater bodies that ordinary Ghanaians see and experience daily (Babayemi et al., Reference Babayemi, Nnorom, Osibanjo and Weber2019).

Furthermore, it is common for some local communities in Ghana to resort to burning as a means of managing plastic waste. Given its chemical composition, the burning of plastics releases harmful toxins, resulting in significant air pollution that increases health risks for the communities where the burning takes place (Oteng-Ababio et al., Reference Oteng-Ababio, Owusu-Sekyere and Amoah2017).

In addition, population growth drives the use of SUPP as a way of enhancing water security (Stoler et al., Reference Stoler, Weeks and Fink2012). Studies (e.g., Adam et al., Reference Adam, Walker, Clayton and Bezerra2021) highlight how the existence of attitudinal clusters among individuals and demographic segments that favour continued use of SUPP exacerbate the problem. Finally, a lack of detailed understanding of the nuanced context-based determinants of plastic use by consumers in Ghana has limited the design of effective plastic pollution interventions (Adam et al., Reference Adam, Walker, Clayton and Bezerra2021). In the face of these challenges, the government of Ghana has in recent years taken steps to put regulatory frameworks and policies in place to better facilitate the management of plastic waste and support the adoption of recycling as a preferred waste management method.

Ghana’s Ministry of Environment, Science, Technology, and Innovation (MESTI) spearheaded the launch of Ghana’s National Plastic Management Policy (NPMP), with a revised draft adopted in 2021 (Ghana Ministry of Environment, Science, Technology, and Innovation (MESTI), 2020). This policy intends to chart a course towards holistic plastic waste management throughout the plastics life cycle and value chain, which sets the foundation for a transition to a true plastics circular economy in Ghana. To achieve this, the policy is designed with the underlying aim of reducing the environmental burden of plastic waste and promoting responsible plastic waste management practices (Osei-Bonsu et al., Reference Osei-Bonsu, Kwabena Mintah, Appiah and Mensah2023).

In addition to the NPMP, the government of Ghana has also formulated and adopted the National Environmental Policy (NEP). This policy, introduced by MESTI, provides a more fundamental framework and guidance for environmental protection in Ghana. It should also be noted that the NPMP is significantly underpinned by the NEP (Osei-Bonsu et al., Reference Osei-Bonsu, Kwabena Mintah, Appiah and Mensah2023). The NEP indicates the government’s commitment to addressing environmental challenges, including plastic waste management, while promoting the responsible use of resources in development. As such, the core principles of the NEP were incorporated within the policy formation and implementation of the NPMP (Osei-Bonsu et al., Reference Osei-Bonsu, Kwabena Mintah, Appiah and Mensah2023).

While Ghana appears to have some policy frameworks in place that are designed to encourage and facilitate good plastic waste management practices, the data on how much plastic waste is collected for recycling in the country (as noted earlier, 9% of plastic waste is collected for recycling) point to the existence of challenges regarding the implementation of these policies and whether they are comprehensive and broad enough in scope. One such challenge is plastic waste collection. Effective plastic waste management in any country requires equally effective plastic waste collection strategies with effective waste collection systems to ensure the enhancement of sustainable practices and the curbing of plastic pollution (Geyer et al., Reference Geyer, Jambeck and Law2017).

Ghana has a collection of both commercial and domestic infrastructure for plastic waste management. However, the scope of this plastic waste infrastructure does not extend to cover major parts of the country. This is partly because neither the NEP nor the NPMP makes it a strict requirement for commercial operators or local residents to segregate their plastic waste for collection. As a result, there is little demand and/or incentive to expand plastic collection services by the government and private sector across the country (Nnaji et al., Reference Nnaji, Afangideh, Udokpoh and Nnam2021). This inference is strongly evidenced in the concentration of formal plastic waste collection services in urban areas in Ghana (Adam et al., Reference Adam, Walker, Clayton and Bezerra2021), with rural and remote communities having no access to such services. This disparity in coverage is a direct result of a policy failure that has resulted in a disincentive for the expansion of formal plastic waste collection services across the country (Nnaji et al., Reference Nnaji, Afangideh, Udokpoh and Nnam2021).

In the absence of robust plastic waste collection streams, the ambitions and vision of both the NEP and NPMP in facilitating effective plastic waste management, as a key driver of sustainable development, has become exceedingly difficult to translate into reality. Ghana’s policy landscape in regard to plastic waste management is similar to a jigsaw puzzle missing critical pieces. It is intricate and multifaceted, with various strategies aiming to create a sustainable and environmentally responsible approach to plastic waste and the nation’s overall development. However, the lack of effective plastic waste collection undermines the very foundation of these policies, making them akin to scattered puzzle pieces waiting to be connected. Therefore, to effectively address plastic pollution in West African countries such as Ghana, a detailed understanding of the aspects that can enhance effective policy making is imperative.

Methodology

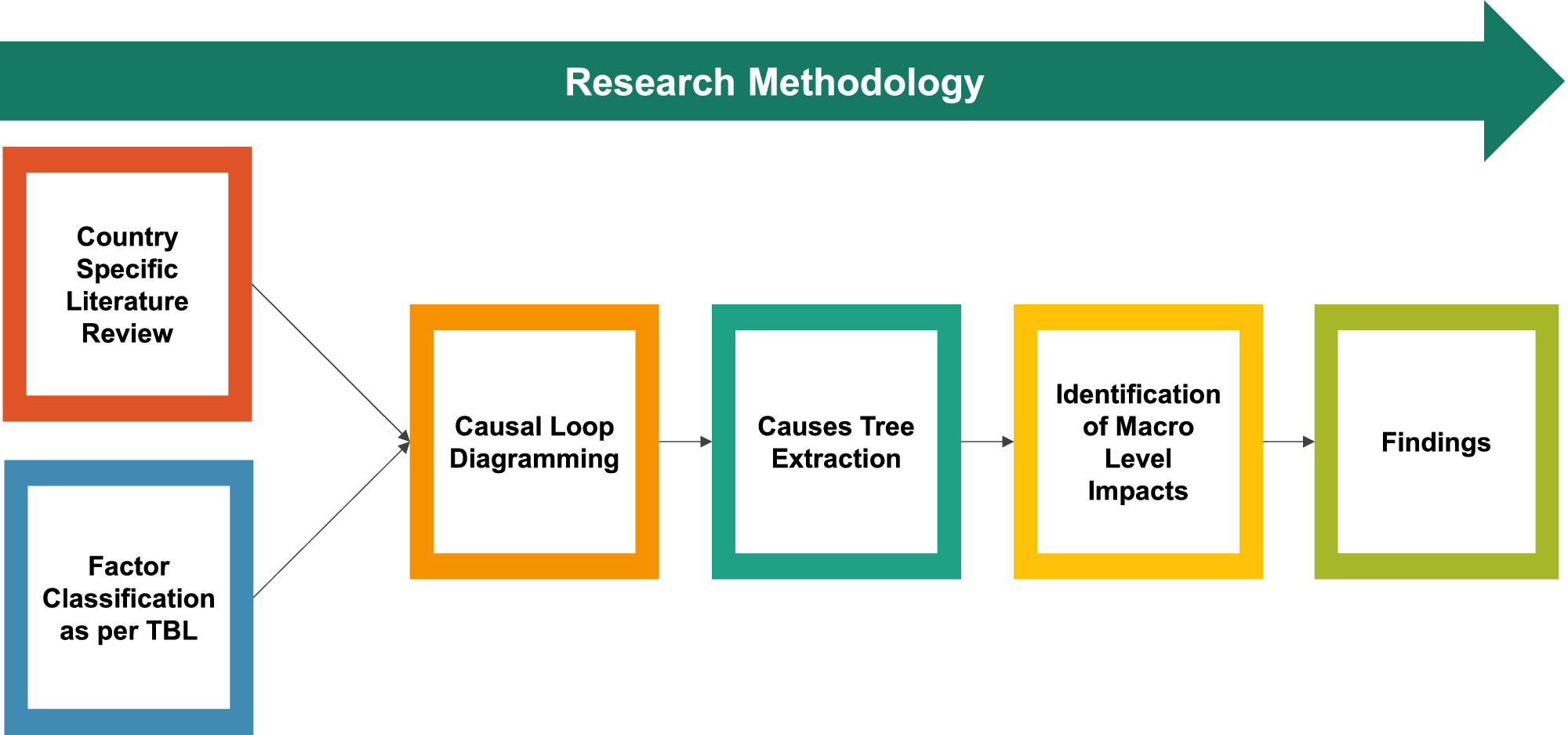

The methodology adopted for this qualitative study is exploratory, embracing narrative extraction and causal loop diagramming (CLD) to demonstrate the impacts of plastic pollution in Ghana. To identify macro impacts associated with plastic pollution within the Ghanaian context, a comprehensive narrative literature review was conducted. The search terms and expressions used to identify relevant studies included but were not limited to the following or their suitable combinations: “plastic pollution West Africa”, “plastic(s) pollution Ghana”, “plastics pollution impact Ghana”, “single-use plastic impact Ghana”, “policies on plastics in Africa”, “laws on plastics pollution policy Ghana”, “laws on plastics in Africa” and “legislation on plastic in Africa”.

The identified impacts within the literature were then categorised in line with the three pillars of the triple bottom line (TBL). The TBL framework is “a simple and increasingly popular way to organise thoughts and action on sustainability” Mitchel et al., Reference Mitchel, Curtis and Davidson2008), making it relevant for addressing the specific aim of the study, that is, to explore the negative social, ecological and economic impacts of plastic pollution in Ghana.

There were studies that pointed towards more than one impact, and they were therefore duplicated in the categorisation process. The identified factors were then used to construct a CLD, denoting the positive or negative impacts of the identified factors within the context. A CLD, as a systems thinking tool, is one of the techniques of system dynamics and aims to establish the cause and effect of different variables in a given system (Azizsafaei et al., Reference Azizsafaei, Hosseinian-Far, Khandan, Sarwar and Daneshkhah2022). Following the construction of the CLD, a causes tree was extracted to visually demonstrate the impacts of plastic pollution in Ghana.

The phases of the study methodology are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Study methodology.

Results

Social impacts

One of the functions to support waste management practices is waste collection. Waste collectors, also called waste scavengers, view waste as a resource; their work provides them with earnings and supports their livelihood. This waste collection is managed formally and informally. Formal services are often operated by the private sector, which focuses on collection and transport. Because these formal waste management services are operated by private companies, the costs are reported to be higher, which excludes those who are not able to pay, thereby creating a form of inequity (Chalfin Reference Chalfin2014). However, waste collection activities elevate the risk of exposure to toxic and unhealthy materials (Owusu-Sekyere, Reference Owusu-Sekyere2014). The study by Owusu-Sekyere, which was conducted in Kumasi, Ghana, revealed the daily exposure of waste scavengers to health problems.

A study conducted in the Sabon Zongo community in Ghana argues that undertaking localised research provides a vivid picture of the challenges and impacts of poor sanitation, including the high prevalence of solid waste such as plastics (Owusu, Reference Owusu2010). The study also highlights that poor governance and lack of decisive action by local authorities have exacerbated the issues within the studied community.

Ecological impacts

An instance of an unsustainable practice in plastic waste management is the use of plastic bottles and sachets to sell ice water to transit vehicles in sub-Saharan Africa, including Ghana. This is particularly examined by Fobil and Hogarh (Reference Fobil and Hogarh2006), who argue that the plastic waste from the unsustainable disposal of sachets has negatively affected the visual appeal of the land and neighbourhoods. In fact, it was reported that in 2017, 1.631 sachets were used per person per day in Ghana, leading to 14,000 tonnes of high-density polyethylene (HDPE) or low-density polyethylene (LDPE) packaging just from water sachet use (Wardrop et al., Reference Wardrop, Dzodzomenyo, Aryeetey, Hill, Bain and Wright2017).

The issue does not solely revolve around macroplastic waste in Ghana. The presence of microplastics and nanoplastics in waters of the country also presents a significant risk to aquatic life and the pertinent ecosystem, and in turn, this may pose concerning health challenges along the food value chain. Research conducted in 2016 examined littering practices in Ghana’s Accra–Tema coastline; the study that examined four particular beaches along the coastline revealed that plastics accounted for 63.72% of all debris collected. Additionally, the authors deemed policy and education as two possible corrective interventions (Van Dyck et al., Reference Van Dyck, Nunoo and Lawson2016). In a study conducted by Adu-Boahen et al. (Reference Adu-Boahen, Dadson, Mensah and Kyeremeh2022), a positive correlation was found between the load of microplastics in Akora River (Central Region of Ghana) and fish loads within the river. The microplastics in fish were also positively correlated with the load of microplastics within water.

A high percentage of plastics are often disposed of at landfills or incinerated in open spaces in communities, which pollutes the air with harmful gases such as sulphur oxides, carbon monoxides, nitrogen oxides and methane. These gases pose significant health risks to humans and animals and exacerbate climate change (Debrah et al., Reference Debrah, Vidal and Dinis2021).

Economic impacts

A study by Bening et al. (Reference Bening, Kahlert and Asiedu2022) examined 80 waste management value chains in Ghana and outlined 67 relevant economic indicators. They reported that street waste collectors play a key role in the value chain yet are the poorest and receive the least earnings throughout the chain. Middlemen and aggregators (second and third nodes within the studied value chain, respectively) play an instrumental role in providing social security for the pickers. The examinations of the quality of waste between formal and informal recyclers also indicated that informal recyclers provide a higher quality of ‘recyclate’, despite the lower earnings.

Macro impacts of plastic pollution in Ghana

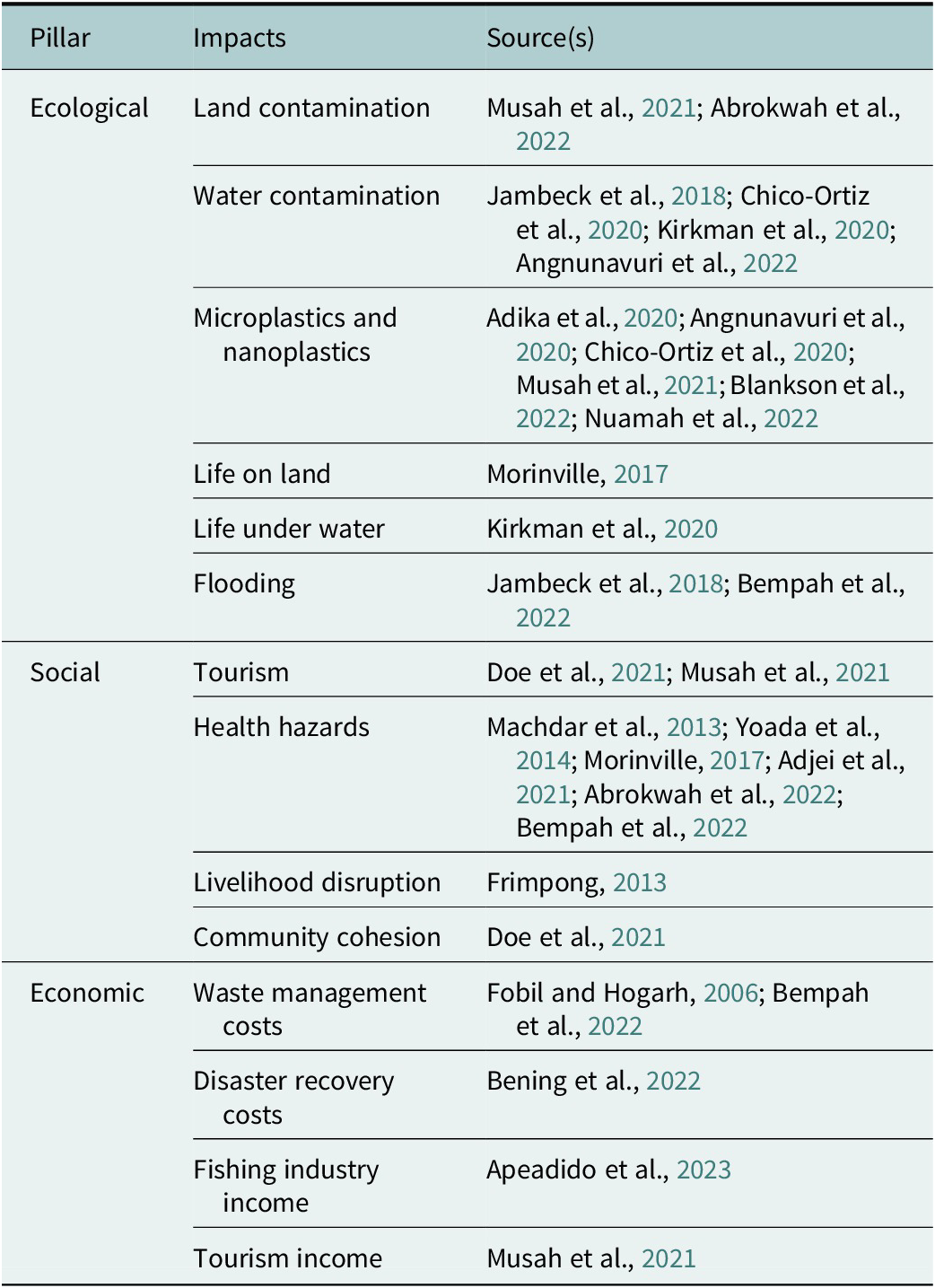

In this section, we summarised and classified the impacts of plastic pollution in Ghana. Table 2 outlines the sources in which the identified factors are corroborated, allowing for further classification and organisation of the macro impacts of plastics within the Ghanaian context.

Table 2. Impacts of plastic pollution in Ghana by sustainability pillars

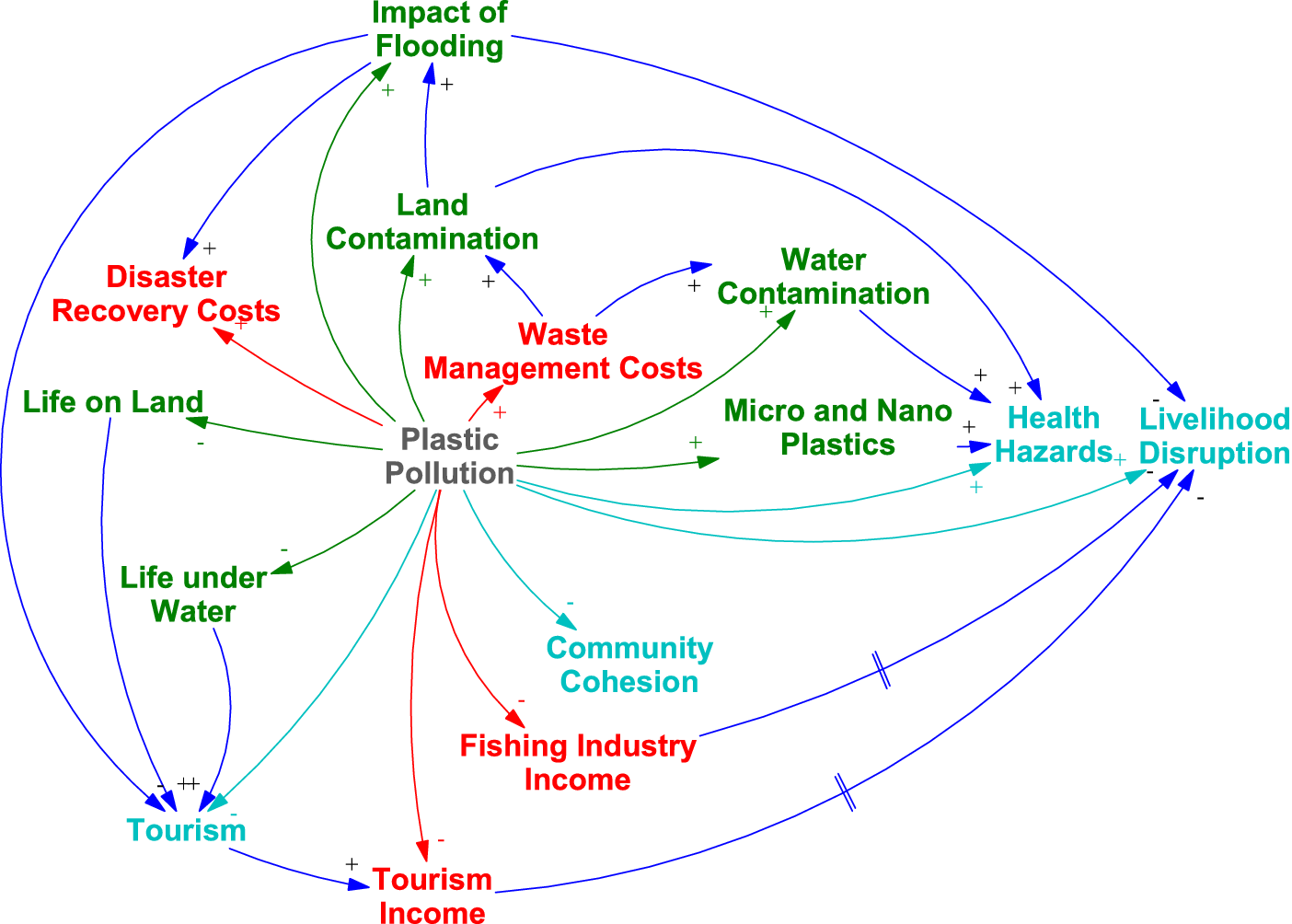

The macro impacts, drawn from pertinent literature and centred on Ghana, were subsequently evaluated from a causal perspective. To illustrate the impacts of plastic pollution in Ghana related to sustainability, CLD was utilised. In Figure 3, the CLD displays three different categories: green variables indicate the environmental impacts of pollution, blue variables denote the societal effects and red variables depict the economic ramifications of plastic pollution in Ghana. Positive and negative signs within the diagram represent favourable and unfavourable causes, respectively.

Figure 3. Impacts of plastic pollution in communities in Ghana (green: ecological, red: economic and blue: social).

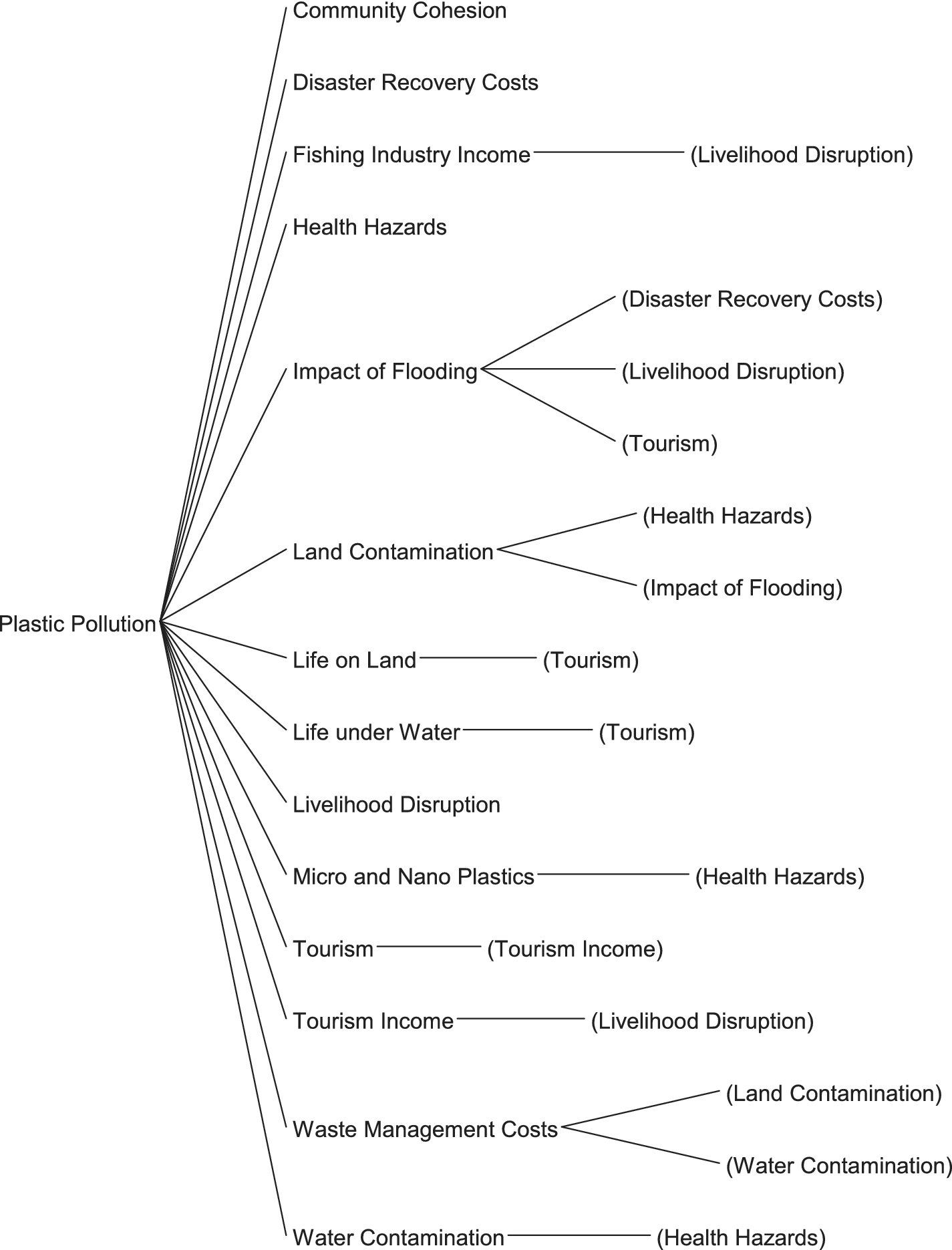

The causes tree, depicted in Figure 4, is developed based on the ‘plastic pollution’ variable, illustrating the cascade of impacts stemming from plastic pollution in Ghana.

Figure 4. Impact of plastic pollution (CLD Vensim Causes Tree).

Considering Figure 3, it is noteworthy to discuss the indirect impacts that certain variables have within the depicted causal model, particularly as they relate to the pillars of sustainability, which have been highlighted through colour coding. As an instance, water contamination influences the income of the fishing industry. This impact extends beyond immediate economic effects, impacting broader ecological and social dimensions such as life on land, thus illustrating a complex interaction between environmental degradation and socio-economic stability.

Moreover, the model currently treats Disaster recovery costs as an exogenous variable. Nonetheless, what is evident is that these costs are themselves influenced by other variables within the causal model. The recovery costs can escalate due to the increased frequency and severity of flooding, for instance, which are exacerbated by environmental mismanagement and climate change. This suggests that disaster recovery costs could also be considered endogenous within the model, warranting a deeper examination of the causes leading to these expenses and their effects on economic pillar of sustainability within this context.

Figure 4 provides a causal tracing diagram to demonstrate the influences and impacts between variables in a complex setting. In this context, it provides a hierarchical view of the influences of plastics pollution at macro level and within Ghana in particular. In other words, plastic pollution is having a negative effect on all three main sustainability pillars in Ghana.

As part of this causal tracing activity, some variables are repeated appearing in brackets in the causes tree (e.g., health hazards, tourism, etc.). This simply denotes that an instance or version of a variable is being referenced at any point in the model. This feature, although not being used in this study, is very helpful to ensure the accuracy of model simulations, should the model is quantified and simulated.

Discussion and recommendations

There are several macro-level impacts of plastic pollution on communities in Ghana that have detrimental effects on the economy, the environment and public health. To mitigate these impacts, the government needs to facilitate initiatives that address plastic pollution by aligning current and future government policies with plastic waste management interventions implemented at the community level.

The following recommendations provide valuable insights and actionable steps that policy makers, commercial and non-commercial actors can adopt in addressing the issues of plastic pollution in Ghana. First, establishing and enforcing bans on SUPPs would limit the extent to which they rely on everyday social and economic settings in Ghana. If it is to be effective, any enforcement of a ban on single-use plastics would need to be accompanied by a robust set of sanctions and/or incentives to encourage compliance.

Promoting recycling practices while simultaneously ensuring the establishment of robust plastic waste collection and management systems is also key to mitigating the adverse impacts of plastic pollution in Ghana. By encouraging recycling, policy makers are able to prevent plastic waste from ending up on landfills and choking open drains, thus reducing risks to health from diseases such as malaria. Policy makers will need to reassess the scale and potential of existing recycling infrastructure and the effectiveness of waste management protocols. This exercise must have at its heart the goal of implementing a nationwide plastic waste management strategy that is underpinned by a robust plastic waste collection system with wide coverage. In addition to this, and considering the impacts identified in this study and the current efforts by the Ghanaian government to address plastic pollution, further recommendations are proposed to enhance the efficacy of the NEP and the NPMP. Accordingly, the policymakers should mandate the segregation of plastic waste at source for both commercial operators and local residents. This policy enhancement should be supported by stringent regulations and incentives to encourage compliance. Moreover, expanding plastic waste collection infrastructure and services to include rural and remote areas will ensure a more comprehensive and equitable approach.

Concurrently, empowering local communities through capacity building focussed on plastic waste reduction and pollution mitigation can provide the basis for the establishment of designated and locally run plastic collection centres to further lessen the impacts of plastic pollution. Such a holistic and comprehensive approach is essential for building a robust practical framework to improve plastic waste management in Ghana and reduce the negative macro impacts of plastic pollution on local people. It is important to increase public awareness through educating the public by delivering workshops and media and presenting research findings, which would help promote understanding of the implications of plastic pollution. Working and engaging with local schools and communities to demonstrate the impact of plastic pollution could also be a strong means of increasing public awareness.

Moreover, engagement with businesses throughout Ghana and the provision of commercial incentives to encourage the production and adoption of biodegradable, biocompostable and/or environmentally safe packaging alternatives would help to not only encourage but also promote eco-friendly substitutes for plastics. Leveraging the use of technology for innovative waste-to-energy solutions also presents a promising means for policy makers to mitigate the negative impacts of plastic pollution in Ghana. Given Ghana’s occasional energy shortages, such cutting-edge applications can help boost the country’s energy generation in a sustainable way while revolutionising the way plastic waste is managed. It is worth highlighting also that this approach would create significant economic opportunities for the local economy and contribute to a cleaner and much healthier environment for Ghanaian communities.

Policy makers in Ghana must take tangible steps to foster strong international partnerships with key stakeholders to ensure effective technology transfer. Collaborating with international organisations, NGOs and governments provide access to essential expertise, funding opportunities and other resources that can significantly enhance Ghana’s efforts to address the macro impacts of plastic pollution. By engaging key international partners, Ghana can benefit from the exchange of innovative ideas, which can help it better promote and amplify its interventions to reduce the macro impacts of plastic pollution on its populace and the ecological environments that underpin the local communities in which it lives.

Finally, continuous research and development that focuses on alternative methods for packaging and addressing plastic pollution is essential. Continuous research and assessment of environmental public health, the economy and information that helps deliver policy decisions will go a long way towards ensuring that Ghana’s long-term plans to address plastic pollution are always informed by the latest knowledge and waste mitigation strategies. The recommendations outlined above are multifaceted and require the involvement of several key stakeholders, such as the Government, community, business and partners. It is imperative to address the impact of plastic pollution with a long-term lens to address the socioeconomic impacts of plastic pollution.

Conclusion

The research conducted offers a comprehensive assessment of the ramifications of plastic pollution in Ghana. It not only evaluates environmental effects but also considers societal and economic impacts. Although the findings may have broader applicability beyond Ghana, they are most relevant to the Ghanaian context.

For future research, it is recommended to investigate the health effects of plastic pollution using established measures such as quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) or disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). Determining the most appropriate measure requires a comprehensive evaluation to accurately assess the health outcomes associated with plastic pollution, as suggested by Sedighi et al. (Reference Sedighi, Varga, Hosseinian-Far and Daneshkhah2021). This approach will ensure that the selected metrics are best suited to capture the specific impacts of plastic waste under various environmental conditions and for the appropriate impacts. Additionally, in our study, we have provided a number of economic consequences from plastics pollution in Ghana. Nevertheless, exploring the economic implications of plastic pollution on the Ghanaian economy from a micro perspective could provide a number of additional research pathways. Furthermore, the study employed qualitative causal modelling to holistically analyse these pollutants within the context of the three pillars of sustainability. To enhance this, future work could involve a quantitative assessment, possibly through scenario analyses specifically tailored to the Ghanaian context. Although using Figure 3, we have illustrated the causal effects of plastics pollution in Ghana from a holistic perspective, future research pathways can also entail examining indirect effects between some of the included variables and re-evaluating the nature of certain variables. Accordingly, further revisions to the model will be able to reflect a more current representation of reality and also enhance our understanding of the dynamic interactions between environmental, economic and social factors. Acknowledging, refining and explaining these indirect connections are crucial for developing comprehensive strategies aimed at mitigating the adverse impacts discussed and promoting sustainable practices across all dimensions.

Finally, although the findings in our study are primarily applicable to Ghana, they provide valuable insights for West African nations, and other low- and middle-income countries with a similar socio-economic profile. The negative impacts and the recommendations provided regarding plastic pollution mitigation could serve as a model for these nations, particularly those in the sub-Saharan region, which may face comparable ecological and socio-economic conditions.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/plc.2024.18.

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article itself.

Author contribution

Conceptualisation: A.H.-F.; Data curation: A.H.-F.; Formal analysis: A.H.-F.; Funding acquisition: A.H.-F., L.L., C.D.U., D.S., S.D., O.O.; Investigation: A.H.-F., L.L., C.D.U., D.S., S.D., O.O.; Methodology: A.H.-F., C.D.U.; Project administration: A.H.-F., L.L., C.D.U., D.S., S.D., O.O.; Resources: A.H.-F., S.D.; Software: A.H.-F.; Supervision: D.S.; Validation: A.H.-F., L.L., C.D.U., O.O.; Visualisation: A.H.-F.; Writing – original draft: A.H.-F., L.L., C.D.U., D.S., O.O.; Writing – review and editing: A.H.-F., L.L., C.D.U., D.S., S.D., O.O.

Financial support

This research was supported by funding from the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Development Office (FCDO), UNCTAD, and UK aid and under the Sustainable Manufacturing and Environmental Pollution (SMEP) programme (Grant No. SMEP C_004_Blue Skies_0932).

Competing interest

The authors declare none.

Comments

We would like to submit the manuscript titled “Macro Impacts of Plastic Pollution on Communities in Ghana” to be considered for publication in Cambridge Prisms: Plastics. In recent decades, the proliferation in the production of single-use plastics has significantly contributed to a surge in plastic pollution on a global scale. Researchers have extensively investigated the impacts of plastic pollution across various regions, yet a comprehensive holistic and location-based understanding of these impacts in the West African context is often lacking. This research addresses this gap by systemically assessing the repercussions of plastic pollution, with a specific focus on Sub-Saharan Africa, particularly Ghana.

Within this study, we have adopted a casual loop diagramming to depict the identified and extracted factors through narrative extraction. We have also presented a holistic view of the impacts of plastic pollution in Ghana, using a causes tree. Please note that the study is part of a funded project aiming to mitigate plastic pollution in Sub Saharan Africa.

We are confident that Cambridge Prisms: Plastics features an audience that continuously seeks solutions to different science and environmental issues. We confirm that this manuscript has not been published elsewhere and is not under consideration by another journal. All authors have approved the manuscript and agree with its submission to the Journal. We would like to thank you in advance for your time and consideration.