Introduction

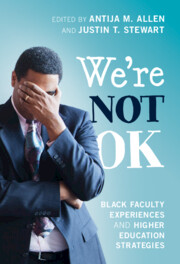

Inequities in representation associated with race are substantial across the United States of America, as evidenced by the lack of African-American faculty in colleges and universities. In fall 2018, of the 1.5 million faculty in degree-granting postsecondary institutions, 54 percent were full-time, and 46 percent were part-time. Of the full-time, roughly 75 percent were made up of white males and white females, while Black males, Black females, Hispanic males, and Hispanic females accounted for 3 percent each (National Center for Education Statistics, 2020: 150–3). Such a low percentage relative to the population illustrates the limited diversity among professors in higher education. Among faculty of color working at predominantly white institutions (PWIs), concerns regarding tenure, advancement, and retention remain constant as they fight to dispel any negative perceptions, fueled by biases, to be accepted and legitimized by their white colleagues and students. The manifestation of these perceptions has created hostile environments, with both covert and overt acts of racism directed at the intelligence and ability of Black faculty, all of which have proven to diminish paths to future opportunities. With these societal perceptions, a lack of representation and a sense of isolation, Black faculty feel pressure to resist their cultural identity and are challenged on how to approach the idea of being authentic within the classroom.

America is fascinated by the culture of Black people, but that admiration is not always present in the engagement of Black people. From a consumer base, Black culture’s mainstream popularization has inspired lingo, fashion, entertainment, and overall lifestyle within the US. (Reference HarrisHarris, 2019). The legacy of Jim Crow laws, the Great Migration, the civil rights movement, and now Black Lives Matter, however, has repeatedly demonstrated how the country perceives the people within this culture, being treated, at best, as second-class citizens. The strength of media outlets is also influential in groups developing negative opinions about one another based on prejudices and stereotypical portrayals, along with creating a social caste system that promotes structural racism. This hierarchy has been a factor in the self-consciousness of African Americans – being the lower tier and made to feel as though they are lesser than. Descriptors like “violent,” “aggressive,” “loud,” “poor,” “ghetto,” “angry,” “emotional,” and “unintelligent” have profiled Black men and women in a history that can be traced back to the Minstrel Shows and Blackface of the nineteenth century (Reference ClarkClark, 2019). In a society where others are threatened by skin color, and complexion can be prioritized over character, Black people have found themselves at risk on a professional and personal level. As a defense mechanism, these marginalized groups have been raised to suppress their holistic selves in the presence of white culture, sometimes regarded as the “dominant culture,” from adolescence onward.

Existing with the “double consciousness” identified by sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois, Black people are observing themselves through the eyes of the majority (Reference Du BoisDu Bois, 1903). Some feel this to be a requirement to present themselves in a manner that is “socially acceptable.” Conflicted, however, by the assumptions of what others expect you to be, as opposed to who you are, these individuals are obligated to hide aspects of their natural presentation in professional settings while adapting to standards mandated by a white, male culture. Unfortunately, this often feels like a prerequisite for a Black person to be successful in America. While some debate this as superficial and performative, others deem it a necessary evil to establish credibility within predominantly white spaces.

When defining a professional or a leader, what are the qualities, traits, or images that come to mind? When picturing a professor, what does that individual look and sound like, and how do they behave? What does Google show you? Our perspectives, and the standards fulfilling these descriptions, can be problematic for outliers outside this prototype, and as a result, an unnecessary amount of pressure is applied to these perceived outsiders to fit into what is deemed acceptable (Reference StithamStitham, 2020). These implicit biases are components of institutional racism and sexism, which has seeped into the fabric of higher education, impacting minority and female faculty.

Teaching at PWIs, and being immersed in a predominantly white culture, requires a sense of duality for African-American faculty to thrive. As the minority of the staff at these institutions, cultural expressions understood within their community do not easily translate for those unfamiliar with that community. Although culture is a foundational component of personal identity, the potential ramifications of this expression can be a gamble. Carefully navigating their actions throughout these professional spaces, where the idea of “Blackness” can be mischaracterized as inappropriate, finding a way to hide in plain sight and mask aspects of their individuality is critical to being viewed as a competent professional. In turn, this can be an exchange to unlock doors and enable access to the securities that further advance his or her career.

There is raised awareness, and a degree of tact, for Black faculty to exercise context and use the appropriate language with the appropriate audience. They must consciously bite their tongue, or be in tune with their emotions, to avoid the perception of overreacting, which can cause their points to be dismissed. The concept of “Blackness,” and what it represents, is unfamiliar territory for white people and the expression of passion can be confused with being “disruptive,” “aggressive,” or “difficult.” In a Race, Ethnicity and Education paper, Ebony O. McGee and Lasana Kazembe studied the experiences of thirty-three Black faculty members presenting research in academic settings. Twenty-four of those participating reported being subjected to comments regarding their “passion” or energy level. One respondent reported hearing; “He was so energetic and lively with his expressions. … Actually, he was so enthusiastic I thought he was going to do a little dance.” Another reported hearing that he really needed to “tone it down a little” from a white colleague who said the audience might think his passion was “making up for a lack of research subjectivity” (Reference McGee and KazembreMcGee & Kazember, 2015).

As a guest on Inside the Actor’s Studio, comedian and entertainer Dave Chappelle once said, “Every Black American is bilingual. All of them! We speak street vernacular and we speak ‘job interview’. There’s a certain way I gotta speak to have access” (Reference LiptonLipton, 2006). Known for his reflective comedy, such a dose of reality has served in holding a mirror to the state of society. The manner in which a person speaks in personal settings versus professional settings dictates how that individual wants to be perceived or how secure he or she feels within a certain environment. A 2019 survey revealed that 85 percent of Black adults sometimes feel the need to code-switch. Of those participants, 48 percent, with at least a four-year college degree, expressed the need to code-switch, compared to 37 percent without a college degree. Citing negative stereotypes regarding African Americans as the cause, these opinions have left them stigmatized, requiring additional effort to prove themselves, and be accepted in the workplace (Reference DunnDunn, 2019).

Code-switching, a term introduced in 1954 by sociolinguist Einar Haugen, is described as language alterations, or the mixing of various dialects. Once considered a substandard usage of language, code-switching occurs when speakers alternate between languages or dialects within a single conversation. According to William B. Gudykunst, code-switching facilitates several functions: To mask fluency and memory in a second language; move between formal and informal conversation; exert power over another; and align with and unify among familiar groups in certain settings (Reference GudykunstGudykunst, 2004: 1–40). Since Haugen, linguists have studied code-switching to identify when it occurs, while psychologists examined why it occurs, with particular interest in members of minority ethnic groups.

The act of altering language is not a new phenomenon, as people shift several times in a single day based on their interactions. There is a difference in how we communicate with parents, lovers, children, friends, and strangers. While still presenting yourself, there are certain aspects that are more prominent based on the dynamics of the relationship that boil down to context. The difference, when compared to code-switching, is a sense of authenticity, which is generally not the case with code-switching. As culture is not accepted holistically, the native tongue and expression of African Americans can be detrimental in certain white spaces. And while donning this mask can be seen as playing a character, it lessens the chances of faculty being categorized by a caricature and placates any presumptions another cultural group may have.

Throughout colleges and universities, some Black faculty have resorted to code-switching to assimilate with their white counterparts. By adopting white traits, conscious shifts in speech and presentation help to avert any stereotypes projected by peers and students. In many PWIs, Black faculty make up a small population, and being the token can add pressures to be the standard for all of their culture. “Talking white” can ease narratives, and in return, improve their prospects for future success and longevity in academia. As societal norms are dictated by the majority white culture, the idea of “whiteness” is the benchmark of normalcy and credibility.

Faculty of color, however, face a crossroads on whether the risk is worth the reward. The experiences of code-switching, positive and negative, differ from individual to individual. Downplaying ethnic traits has increased the perception of professionalism and the likelihood of being hired. By avoiding stereotypes, minorities can also be identified as having leadership qualities and afforded such opportunities. The other side of the coin, however, carries the burden of identity crisis, appearing “fake” with colleagues of your culture by projecting a false image to avoid being labeled the prototypical Black person. Simultaneously combatting stereotypes and trying to “fit in”, Black faculty spend an inordinate amount of time proving themselves to white people across all levels, from leadership to peers to students. These pressures can lead to burnout for these professors, overcompensating to prove their value to the institution. In making the choice to be or not to be, it begs the question; do you have to be inauthentic to be accepted?

Meeting “the Qualifications”

Whereas earlier applications of code-switching primarily related to spoken language, modern usages have evolved, capturing various forms of language that define self-presentation including speech, appearance, behavior, and expression. This has also been applied to showcase qualifications and experience in job searches.

Marybeth Gasman, a higher education professor at the University of Pennsylvania who studies institutions with high minority enrollment, has described the lack of desire for institutions to hire Black faculty, shining a light on the selection process:

I have learned that faculty will bend rules, knock down walls, and build bridges to hire those they really want (often white colleagues) but when it comes to hiring faculty of color, they have to ‘play by the rules’ and get angry when any exceptions are made. Let me tell you a secret – exceptions are made for white people constantly in the academy; exceptions are the rule in academe.

An article for The Hechinger Report in September 2016 detailed the experiences of Felicia Commodore, an African-American woman with a doctorate in higher education and a slew of published articles. Commodore expressed the difficulties she was having securing a college teaching job, having been regularly rejected. Questioning if race played a factor, she intentionally toned down her cover letter, downplaying any racial references. Having substituted terms like “African-American communities” with “cultural communities,” she was conflicted when she then started to receive more traction from prospective institutions, stating “I wondered whether I wanted to be in a field, academia, where you have to whitewash yourself.” Starting fall of 2016 as an associate professor of education at Old Dominion University at a crossroads, feeling that she had to compromise her identity to be in academia, Commodore understood what was needed to secure a job. Ironically, Commodore would add that, before working on her master’s degree, she had never come across a Black tenure-track professor (Reference KrupnickKrupnick, 2016).

Minority job applicants, in an attempt to increase the likelihood of landing a position, are reported to “whiten” résumés. Deleting references to their race, they increase their chances in the job market. Research conducted by Katherine A. DeCelles, a professor of Organizational Behavior at the University of Toronto, identified bias against minorities during the résumé process at companies across the US. Co-authoring the September 2016 article “Whitened Résumés: Race and Self-Presentation in the Labor Market” in Administrative Science Quarterly, as part of a two-year study, the findings of DeCelles and her colleagues revealed that “whitened” résumés results in more job call-backs for African Americans.

In one study, researchers created résumés for Black and Asian applicants, distributing them to 1,600 entry-level jobs throughout 16 metropolitan sections of the US. Some résumés intentionally reference minority status for an applicant, while others were whitened. Additional techniques involved adopting Americanized names, with Asian applicants substituting “Luke” for “Lei,” and Black applicants toning down affiliations to Black organizations. This scrubbing also applied to accolades, with a Black college senior omitting a prestigious scholarship from his résumé due to fear of his race being discovered. Data from these studies revealed 25 percent of Black candidates received callbacks with whitened résumés, compared to the 10 percent who left ethnic cues. The difference was also visible for Asians, with 21 percent callbacks for whitened résumés, contrasted to 11.5 percent without. Ironically, some of the companies that were part of the research identified as being pro-diversity (Reference GerdemanGerdeman, 2017). Of these “equal opportunity employers,” DeCelles noted that discrimination still exists in these organizations, and while they are not intentionally setting up these minority applicants, there is a clear disconnect in their diversity values versus the person screening resumes:

This is a major point of our research – that you are at an even greater risk for discrimination when applying with a pro-diversity employer because you’re being more transparent. Those companies have the same rate of discrimination, which makes you more vulnerable when you expose yourself to those companies.

The Standards of American English: The Sound of Success

In the 2018 film Sorry to Bother You, African-American protagonist, Cassius Green, is a telemarketer struggling to make sales with customers. Seeking help, Langston, his colleague and fellow African American, advises that he use his “white voice.”

You want to make some money here? Then read the script with your white voice … It’s sounding like you don’t have a care. Got your bills paid. You’re happy about your future. You’re about ready to jump in your Ferrari after you get off this call. Put some real breath in there. Breezy like … I don’t really need this money. You’ve never been fired, only laid off. It’s not really a white voice, it’s what they wish they sounded like. So, it’s like what they think they’re supposed to sound like.

Cassius immediately excels in his newfound persona, climbing the ranks and gaining access to newer opportunities. He is, however, unable to lean away from his “white voice” and is urged by another Black co-worker, who has similarly ascended, never to stop using it. By presenting a favorable version of himself, one that made white executives feel comfortable, Cassius is afforded the opportunity to be successful. The central idea of a satirical film – that a voice can propel a person further than their skin tone – is the reality for many African Americans in the workplace. Director Boots Riley, spoke as a guest on CBS This Morning, expounding further and stating:

Everything is a performance. In the movie, the white voice that they use is this sort of mythical thing that says ‘Everything is okay’. That’s like the performance of whiteness for some folks.

The idea of adopting a “white voice,” and what a person thinks they should sound like, is a tool to reach the desired outcome. Within traditionally white spaces, “sticking to the script” has enabled Black and other racialized communities to navigate effectively to gain access to opportunities. Whether this tactic is right or wrong is a subjective judgment, but for many, playing the game and leveraging politics within the work environment can be an enabler to reach the desired outcome of career advancement. In a study conducted by Shiri Lev-Ari, a psycholinguist at the Max Planck Institute of Psycholinguists in Nijmegen, it was determined that “we’re less likely to believe something if it’s said with a foreign accent” (cited in Reference ErardErard, 2016). When exposed to non-native speaker accents – and taxed with the additional effort of processing unfamiliar speech – our brains are prompted to discriminate against that speaker. Conclusions about a person’s profile relating to level of income, education, or social standing, can be drawn based on linguistic biases (Reference ErardErard, 2016).

While some argue that the English language has been “bastardized,” evidenced by its variations in dialects and the ability to manipulate and introduce new terminology through slang, Standard American English (SAE) still holds overall preeminence. African Americans, while native English speakers, encounter biases due to the dialect shared within their communities, generally referred to as African-American Vernacular English (AAVE) or Black English. Not widely accepted outside this culture, it has been described as “broken English” or speaking with “poor grammar,” and is regarded as a display of low intelligence or lack of education (Reference RettaRetta, 2019). J. Michael Terry, an associate professor in the Department of Linguistics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, has identified an unequal valuation of languages in different spaces: “Those characteristics of language that become associated with people of color have such negative connotations and are viewed from the outside as being somehow not only different from but defective. And that’s part and parcel of a view that says that people of color are somehow defective” (cited in Reference WesleyWesley, 2021). He added that while many people deviate from SAE, some deviations are marked in terms of class and do not count against you in the same way as those that are racially and ethnically marked.

Fluidity in conversation – being able to adapt speech to a particular audience – has been viewed as a strength that is used to great benefit by some Black faculty. To many, the ability to connect effectively with people from different social skills is a valuable trait. In Reference HarrisHarris, 2019, professors shared their personal experiences, with some finding benefits and others expressing frustrations. Georgetown sociology professor Michael Eric Dyson has stated that he frequently code-switches in many of his speeches across the globe, going from “highfalutin theoretical discourse down to gut bucket reality.” Dyson feels it is a necessity for the protection and preservation of Black culture: “We have to speak in front of white folk who understand what we are saying so we have to be covert with it” (Reference HarrisHarris, 2019).

Business psychologist and coach Dione Mahaffey has leveraged the practice throughout her career. While tiresome, she understands the need to negotiate within white spaces:

It’s exhausting, but I wouldn’t go as far to call it inauthentic, because it’s an authentic part of the Black American experience. Code-switching does not employ an inauthentic version of self, rather, it calls upon certain aspects of our identity in place of others, depending on the space or circumstance. It’s exhausting because we can actually feel the difference.

Mahaffey continues to describe code-switching as an exchange, requiring give and take. She has used these performative niceties to her advantage when working in white spaces to learn what she needs, secure what she requires, and use it to create and build.

While this assimilation to standard language has proven to be successful for some, opposition remains toward the practice, with many perceiving “talking white” as a suppression of cultural expression. Derrick Harriell, poet and associate professor of English and African-American Studies at the University of Mississippi, has expressed his regrets with code-switching and has since made the decision to stop:

I know certain forms of code-switching have been responsible for saving our lives as Black people and key to our survival, so in that way, I’m not judgmental. I understand that my ability to not code-switch is a privilege, but it’s also a privilege my people died for, therefore for me, I have to [be myself] or else I feel as if I’m doing my ancestors a disservice. Amongst the Black community, there are those rejecting the notion of conformity in code-switching, feeling the sacrifice is too much. Culture is a foundational and an integral part of identity that should be expressed, but these shifts require an individual to dilute the idea of being the “best version of me.”

Myles Durkee, assistant professor of psychology at the University of Michigan, has done extensive research on racial code-switching, and detailed the added burden that code-switching can create for Black professionals:

We actually find in our data with Black professionals that those who tend to code-switch more frequently, also report significantly more workplace fatigue and burnout from their current positions. Simply, because they have to be a different person and mask all the cultural assets that they probably value and appreciate internally. But they realize that those same traits aren’t valued in their workplace. So they have to bring a completely different person to the workplace and basically keep that personality on throughout the workday. That can just be draining and likely will lead to mental health consequences, Durkee said.

Token Black Faculty: The Pressures of Fitting In

As an outlier in PWIs, Black faculty face increasing insecurity, due to a lack of representation. This insecurity stems from the pressures of being one of a few, if not the only, faculty of color, which can cause these individuals to have higher visibility and be singled out for their racial identity. According to the National Science Foundation, only 6.4 percent of US citizen or permanent resident research doctoral recipients were Black and 6.5 percent were Hispanic (Reference KrupnickKrupnick, 2016). Additionally, while 13.3 percent of education doctorates are awarded to Blacks, they receive 3.5 percent of doctorates in the physical sciences. This disparity in representation creates an environment where these faculty members find themselves overworked in areas including diversity initiatives and hiring committees. As a small fraction of the community, being one of a few, if not the only, faculty of color, these tokenized Black professors implement code-switching to help avert any discrimination based on assumptions associated with their cultural identity.

Dating back to 2008, Black women in faculty positions remain underrepresented, showing little or no growth. African-American women were only 2 percent of all women faculty members in PhD departments, 3 percent of women faculty members in bachelors-only departments and 0 percent in masters-only departments (Reference Porter and IviePorter & Ivie, 2019). Feelings of isolation and alienation have prompted these faculty to minimize their presence among male colleagues. In May 2020, The Physics Teacher journal reported that Black female faculty working in physics experience hyper-visibility, and as a coping mechanism, alter their behavior to counter any discrimination based on gender and racial stereotypes (Dickens, Jones & Hall, 2020). Women resort to “identity shifting” and intentionally change their behavior to appear less physically feminine and become more masculine verbally, or make other behavioral changes to be accepted. Assimilating to a predominantly white male culture, women have changed the tone of their voice to prevent it being mistaken for threatening. This shifting has yielded benefits for Black female faculty navigating these spaces, enabling them to make connections and build networks (Dickens, Jones & Hall, 2020).

While these strategies have been leveraged to counteract negative assumptions of what a Black man or woman is, or should be, within the workplace, having to become a minimized version has led to internal obstacles. Marla Baskerville Watkins, Aneka Simmons, and Elizabeth Umphress detailed these challenges in an analysis of eighty studies of token employees that had been undertaken between 1991 and 2016. Watkins commented that:

Our review showed that tokens have higher levels of depression and stress. They’re more likely to experience discrimination and sexual harassment than women and racial minorities who are working in more balanced environments. Research shows people are less satisfied and less committed at their jobs if they’re tokens. Companies should be concerned about this, said Watkins.

In Reference GaNunGaNun (2020), Black professors at the University of Georgia (UGA) detailed their perspectives as students and as faculty in academia. Working at UGA, these faculty members are part of an underrepresented Black population. Reported for fall 2019, only 5 percent of full-time faculty at the institution identified as Black or African American. Among these faculty is Paige Carmichael, a professor of pathology in UGA’s College of Veterinary Medicine, where she has spent her entire teaching career, dating back to the 1990s. As the first African American in her department, Carmichael cited previous instances of microaggressions, to which she used code-switching in an attempt to fit in with the accepted majority. When expressing herself in feeling the need to suppress aspects of her heritage of culture, Carmichael has felt even further diminished due to the responses:

Challenges of Identity within the Classroom

Based on the low percentages of African-American faculty within PWIs, it would not be far-fetched if a student never had a Black professor, and remained accustomed to the traditional image of a professor solely as a white man instead. With limited or no experience of a Black person ever being the authority in the classroom, Black professors are often subject to negative attitudes and inappropriate behavior from students. While performing their duties in the classroom, they must actively manage their engagement within the classroom to resist the pressure to confirm or disprove students’ beliefs that are projected onto them relating to their competence and capacity to be those students’ professor.

Manya Whitaker, an associate professor of Education at Colorado College, has described “stereotype threat” as the experience of confronting negative stereotypes about race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, or social status (Reference WhitakerWhitaker, 2017). Considered a social psychological construct, Whitaker details how people are, or feel themselves to be, at risk of conforming to stereotypes about their social group. Whitaker identifies women faculty who are members of racial minority groups as being most at risk of becoming stereotype threatened, experiencing anxiety about confirming or disproving the beliefs of students.

Whitaker further discusses how students’ personal beliefs of what a professor should be and look like could be projected in the classroom. These descriptions can hold true for the traditional, older white male professor, but they are only a part of the faculty population, not the faculty population. Those that do not fit these criteria are challenged by expectations based on sexual and racial biases:

To complicate matters, students have different expectations for faculty of different ethnic and racial backgrounds. Asian professors, for example, are supposed to be meek but very intelligent while Black professors are expected to be loud and aggressive. Males and females also face far different challenges in the classroom. Men are stereotyped as smarter than women so it’s no wonder that students often challenge women about their qualifications, and evaluate them more harshly than men.

In these instances, Whitaker indicates that these faculty of color and female faculty generally take one of two approaches: (a) confirm students’ stereotypes; (b) disprove their beliefs. In confirming stereotypes, professors are avoiding tension that can come from challenging these perceptions from students, and instead opt to behave in a manner that aligns with the expectation of that student. Black female professors have leveraged false characteristics to become the loud, sexualized Black woman primed and prepped for an argument. In exchange for “method acting,” they are better able to build a strong “relationship” with non-Black students. In disproving beliefs, which is the more common approach, with a weight of self-awareness related to cultural expectations, these professors consciously counter negative tropes. While not blatantly challenging these beliefs, they intentionally play counter to what their assumed behavior should be. The “aggressive” Black male professor, for example, will maintain distance from students, be mindful of his tone and avoid any explicit language.

While these tactics are understandable, Whitaker implores her own approach to simply be herself; a Black, young, Southern female who enjoys football. It is less about combatting what she is perceived as, and more about being intentional when describing who she is. Understanding that students are selective in accepting certain aspects of their professor, being herself, unapologetically, has helped to establish the foundation of these relationships.

Blurring the Lines: Your Personal Space or Your Professional Space

The impacts of COVID-19, and the requirement of keeping people socially distant, necessitated a transition from the usual on-site environment to a remote one for many workers. The home, a previous place of refuge, has become the office, which has presented a hurdle for code-switching as the boundaries of personal and professional space have become blurred. Our personal environments have been breached, now front and center with constant meetings over Webex, Zoom, Skype, and other web conferencing applications. The trigger that was presented when entering the physical office is more difficult now that our private space teeters the line on being the virtual office. Although the convenience of being at home has been embraced, there are additional obstacles as a result of these “living at work” arrangements.

Previously able to choose what they wanted to share, Black faculty are more out in the open with their personal lives on display once the Brady Bunch boxes appear for these virtual meetings. According to Reference McCluney and RobertsMcCluney & Roberts (2020), working from home has signaled the need for code-switching to evolve, with BIPOC making their physical spaces “whiter.” The use of virtual backgrounds or choosing not to turn on the camera are tactics adopted to avoid having at-home lives on display. McCluney, an assistant professor of organization behavior at the School of Industrial and Labor Relations at Cornell University, has described her fear of having her own cultural identity mischaracterized or misunderstood by colleagues due to having African cultural artwork on display that features bare-chested figures.

Shonda Buchanan, author and professor, shared her initial experiences in “Zooming While Black” as she transitioned to working from home. Accustomed to a more relaxed presentation at home, where she had full reign and freedom to be her full self, she has had to maintain awareness now that her living space is being broadcast to professional colleagues:

As soon as my image leapt onto the videoconferencing screen, it dawned on me, a smiling African-American woman wearing a sleek, multicolored headband, that I was probably a little too relaxed in my appearance. I also realized that my colleagues, mostly white and Asian, were seeing me for the first time in my natural, fuss-free cultural state. In the classroom, I wear slacks or a skirt, a blouse, maybe a shawl. My hair is always neatly pulled back. I am prepared for that space. I have cultivated my image there over 18 years of university-level teaching – operating with the understanding that I am a role model by default. As such, I represent Black women and girls everywhere. But in a virtual space, with just my cute smile, unruly locs and quickly typed questions in the chat box, I felt odd and spatially closer than I’d ever been to my colleagues. A little more exposed. A little more vulnerable. Zoom offered a window into our private spaces, and closing off mine, like some others had done, wasn’t an option.

Buchanan continues that while she feels anxious on certain aspects of her cultural identity being amplified through this virtual window, her colleagues, mostly white and Asian, were not concerned at all with their own presentation.

Having a Seat at the Table

One could ask the question: Why is there still a need to code-switch? Surely, the culture of institutions has diversified enough for conformity to be no longer required. While somewhat true on a social level, the demographics of higher-ranking positions at colleges and universities tell a different story. According to 2017 data from the College and University Professional Association for Human Resources, white people held the majority of administrative positions (American Council on Education, no date). These positions include top executive officers, senior institutional officers, academic deans, institutional administrators, and heads of divisions, departments, and centers. With white employees accounting for more than 75 percent of higher education professionals, African-American employees made up less than 15 percent. Although the amount of Black faculty has steadily increased, the positions of power remain occupied, in abundance, by white employees, specifically white males. As the environments of PWIs do not disproportionately impact these individuals, they are less inclined, or incentivized, to dismantle these systems and advocate change. With limited diversity among executive leadership, the discussions, perspectives, and ultimately, actions, are skewed, making progress more laborious without the perspectives of the marginalized groups that are affected.

PWIs must make a shift in broadening their understanding of the plights of Black faculty within these colleges and universities to truly become allies. As guest speaker on the YouTube series Women in Colour, Nicole Neverson, a professor of sociology at Ryerson University, shares some of her internal struggles challenging her peers as the minority:

When you’re navigating a lot of these white spaces that are telling you your body is not a part of this space, or it’s an unfamiliar body in this space, you sort of have to adopt the language and the movements of whoever has normalized that space. So, it’s a very tricky thing and, on one hand it is survival, on the other hand, the way that I look at it, is it keeps on communicating to me who I am. And it keeps communicating to me the spaces where, as Vanessa said, I have to insert myself more. You make choices on “Okay, am I going to say something in this meeting? Am I going to use the physical and emotional energy that I have, to break it down for these people and tell them that this idea that they’ve just proposed, it’s no good?” And, it’s actually not great for most students and it’s only going to serve a certain type of student, and not all, or be more inclusive.

There have been reports, dissertations and articles detailing when and why code-switching is used for people of color, but discussions should also identify organizations that create these environments to necessitate this strategy. In Reference Lloyd and WashingtonLloyd & Washington 2020, Courtney L. McCluney speaks at length on the subject, based on extensive research she has conducted with a colleague:

I think what makes code-switching a unique phenomenon, that institutions are responsible for creating the need and pressure to code-switch, is that it becomes attached to things that are not necessarily relevant for our given situation. So, I think about this a lot of times in the workplace where currently, in more states in this country, you can fire someone for wearing their hair in its natural state. There are no legal protections at the Federal level protecting someone’s hair texture from being discriminated against and being considered unprofessional.

While legislation from the CROWN Act (Create a Respectful and Open Workplace for Natural Hair), a law passed in California in 2019 that prohibits discrimination based on natural hair texture and style, is now under way in all states and federally, McCluney explains that it illustrates how code-switching requires individuals to deny natural aspects of themselves and, in continuing this adjustment, it provides validation of the stigma that is attributed to Black expression by not challenging it:

The problem with it is, over time, it can contribute to burnout. People are trying to learn to present themselves on top of doing their jobs, or existing in any given space, and that is quite mentally, physically, and emotionally exhausting. On the other hand, it also reinforces beliefs that the norms we have set in place in society are the default, and it is preferred. The norms are so preferred that even this Black person is adjusting how they speak and suggesting that the one right way of being is the white way of being. So, it reinforces the inequality that we are actually fighting against by code-switching and leaning into those ways of speaking, dressing, behaving, etc.

Recommendations

Code-switching revolves around the need for African Americans to be legitimized within professional spaces that are predominantly white. Existing at PWIs, this tool has enabled Black faculty to survive, as well as thrive, but it presents a gap in the infrastructure of these institutions in understanding culture, identity, and diversity, and has led to these professors feeling minimized, unsupported, and required to play a role to be accepted.

Through leadership acknowledging and monitoring any inherent bias against social class and cultural signals in faculty of color, there is an opportunity to re-evaluate expectations and welcome new methods of learning.

Elevating the Diversity of Campus Culture

This chapter has detailed the inequities for faculty of color throughout PWIs. Diversity, throughout all mediums of higher education, is a vital step in building a community that offers unique perspectives, along with showing that representation is a genuine priority.

In devising strategies for their respective institutions, leadership should:

Assess the current diversity of senior leadership, hiring committees, and interview panels to ensure that all voices are present at the table and are representative of the campus population.

Review policies and create criteria for the candidate interview process that seeks the most qualified individuals, while also promoting individuality.

Invest in minority populations by visiting and recruiting talent from historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs), and other underrepresented cultural groups, to diversify the applicant pool of faculty prospects.

Implement faculty developmental programs that expand scholarly activities to identify and develop leaders in the making.

Host social networking events on campus that provide ongoing training for students, faculty, and non-academic staff to encourage interaction and discussion on diversity issues.

Implementing Cross-Cultural Groups and Events

As a minority at PWIs, Black faculty can feel, or be made to feel, like outsiders, struggling to fit in with standards that are not naturally representative of their respective cultures. PWIs should establish spaces within the workplace that encourage discussion on diversity-focused topics. These platforms should allow open dialogue to deconstruct implicit biases, which can help provide faculty of color the freedom and comfort to connect and freely express themselves without fear of reprimand. To drive efforts forward in creating a more inclusive environment, institutions should:

Increase the amount of engagement channels to stimulate conversation among faculty with outlets such as Lunch and Learn sessions and Employee Resource Groups (ERGs) to champion diverse communities (for example, African American, Asian American, LGBTQIA+) and build cultural awareness and understanding across the campus population.

Facilitate intimate focus groups/fireside chat sessions with a diverse panel of faculty and administration to share critical, thoughtful dialogue on experiences and challenges within the workplace.

Partner with neighboring colleges and universities for networking events to expand professional connections and find new opportunities to connect with potential mentors and supportive colleagues.

Administer quarterly surveys to faculty and administration through online platforms to gather feedback and insight that can identify opportunities to improve the work environment and increase overall job satisfaction.

Moving Forward as Black Faculty in PWIs

As a person of color at a PWI, the struggle of identity and authenticity remains the conundrum of being visibly Black while trying to avoid being the stereotypical Black. It is the difference between feeling safe or insecure in your own skin. The acceptance of appearance with the rejection of assumed behavior that comes with being Black has muted opportunities to learn how that culture can effectively be integrated into the workplace instead of imposing a single “white is right” standard.

For faculty of color, the demands of daily code-switching, juggling the presentation of yourself with teaching, and assessing the culture of your institution, will ultimately lead to a decision about remaining in or departing from that system. The need to be constantly “on” can be physically, emotionally, and psychologically exhausting in trying to express yourself without falling into negative cultural expectations. It is pertinent to observe and evaluate the environment within the institution thoroughly against the values that you hold for yourself. Achieving success may be your goal, but when this is at the expense of happiness, is it worth it? In developing your own sense of safety, you should be immersed in spaces that nurture who you are instead of feeling forced to overcompensate for what you are not. Ultimately, this decision rests with you.