We understand globality as the human ability to inhabit and connect every corner of the planet, thereby enabling humans to become a ‘geological force’ capable of modifying the planet’s rhythm through their political, commercial, and technological activities, as the historian Dipesh Chakrabarty would say. Footnote 1 The advent of globality was a slow process that took place as the globe was discovered by European explorers and its parts became politically connected. Up until the fifteenth century, this definition of globality was unthinkable. Scholars, chief advisers to European courts, and elites still promoted the ideas of the ancient cosmographers who had proclaimed the existence of vast, uninhabitable areas, such as the Torrid and Frigid Zones. The pillar of this conception was a climatic theory that delimited and categorized the world into zones. This set of geographical, cosmographic, and theological ideas and notions, many of them developed without any experience in the regions in question, informed the concept of habitability. Footnote 2 Triggered by late fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century European overseas explorations, the transition from that image to a new construct in which the entire world was potentially inhabitable by human beings was a tectonic geographical change that altered the European spatial imagination of the world. Footnote 3

This change relied on the European discovery and understanding of the so-called ‘southern region’ of South America, spanning from Patagonia to Antarctica. This region included the Strait of Magellan, the passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans ‘discovered’ by Ferdinand Magellan in 1520, which allowed all of the world’s maritime routes and regions to be connected for the first time. Footnote 4 Until that year, the southernmost point of the known world was marked by the sea routes of Europeans – mainly the Portuguese – around southern Africa, a continent whose southern limit is located at 34° S. The area that interests us here extends from approximately 35° to beyond 60° south latitude.

This glocalized process of producing a new image of the earth encourages inquiry into how contemporaries understood this new connectivity and represented the changes caused by the newly discovered lands. Footnote 5 For this purpose, it is essential to understand the role that the southern zone of America played in creating this new ‘world-consciousness’, both in new ideas concerning the world and in the practical ways of embracing it. Footnote 6 I will therefore analyse how this new connectivity of the oceans was created by the world-passage of the Strait of Magellan, and how it transformed the globe into a fully habitable space and all of its parts into political objects. Footnote 7

This article aims to advance our understanding of how the discovery of this region set this process in motion. Footnote 8 We will analyse this from two perspectives: first, from the perspective of new political agencies generated by the emergence of the Southern hemisphere and the new awareness of the world following the rupture of the limits of the unknown; and second, by trying to answer the question of how that part of the world inspired global thinking. Footnote 9 We will focus on geopolitical–commercial schemes and discussions on habitability that arose in the Spanish court, considering the first circumnavigation as the starting point. We believe that examining and contextualizing this milestone as an event – rather than a mere Iberian nautical feat – are a good way to understand the temporal and spatial ruptures and transitions that it activated in Europe and which influenced subsequent enterprises of conquest.

In general, sixteenth-century political–commercial dynamics have been presented as a total connectivity, with very little attention given to how we became aware of such assemblages, their scales, and the role that some passages and places acquired in this new composition of the world. Scholars have treated the globalization of this period as a phenomenon that occurred simultaneously everywhere – in the same modernity or materiality – when many territories, such as the southern reaches of South of America, were not fully ‘discovered’ until the end of the century or later. Footnote 10 In fact, hardly any works explore the understanding of the world’s new limits or consider the broad cosmographical implications of this region’s emergence on the global scene. Footnote 11

Studies of the sixteenth-century southern zone of America fall short of explaining how the image of the world was reformulated and do not account for the global impact of Europe’s discovery of this area. Some studies have focused on the records left by Ferdinand Magellan’s expedition (but from a nationalist, Chilean point of view), while others have investigated the shipwrecks and failed attempts at settlement, the importance of places like the mythical City of the Caesars, and the chroniclers who referred to it. Footnote 12 In recent years, researchers have focused on the territorial dimensions of the Strait, considering the physical, historical, and imagined conditions of the place, and from certain geopolitical perspectives, such as the settlement or defence of the Strait, demonstrated by their interest in the cosmographer Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa. Footnote 13 Coinciding with historical commemorations of the discoveries of the Pacific and the Strait of Magellan, some researchers have also highlighted the role of the Strait in relation to other spaces, such as the Pacific Ocean and Asia. Footnote 14

Other scholars have studied the symbolic–philosophical conception of the south at this time through references to the famous terra incognita, a hypothetical southern continent. Footnote 15 They have traced its historical evolution since ancient times and shown how famous European cosmographers, such as Sebastian Münster and Gerard Mercator, depicted it as a continent in the second half of the sixteenth century. Footnote 16 However, no study has yet compared this terra incognita with the knowledge generated from the southern reaches of America or the geopolitical processes of conquest that were connected to it throughout the sixteenth century.

The first circumnavigation, the passage to a global scale of commerce

In October of 1519, 237 men in five ships set sail for the southernmost tip of America in search of a passage that could connect Europe and Asia through the western oceans. After a year of voyaging through the Atlantic Ocean and along the American coasts, and several failed attempts to find this passage, in November 1520 Ferdinand Magellan sailed his ships into the strait that bears his name. What followed was the first round-the-world voyage, which ended in September 1522 with only 18 men returning to Spain in the Victoria, captained by Juan Sebastián Elcano. Footnote 17

Due to Magellan’s aims, we can argue that his voyage formed part of a European imperial venture. The principals of its preparation show an eagerness for commerce and strategic positioning in Asia, which can be seen in the agreement signed between Magellan and the King of Spain in March of 1518. This document lays out the guidelines for the voyage’s sailors-traders, ranging from exploration etiquette, including ways to identify the best coasts and lands for colonies, to diplomacy in order to negotiate with the kings of foreign lands and recognize goods that were most important for trade. Footnote 18 Whatever came from the East was of general interest, universal in a certain sense, as we read in the instructions Magellan received:

If you find seed pearl or pearls in any of the places that thee discover, thee shall take the largest and most ‘eastern’ varieties, and if they are pierced, mind thee it be as subtly as possible; and if there are any closed varieties, but round and eastern and unpierced, thee shall not fail to take them… Footnote 19

Initially, the objective that the navigator presented to the court was to find a way to import spices to Europe; however, the documents reveal that precious stones, fabrics, and other exotic objects were also on the expedition’s radar. Footnote 20 In essence, they wanted to establish solid relations with merchants in what were, at the time, the most ‘prosperous markets in the world’. Footnote 21 The Portuguese monopolized the route around Africa to Asia, thanks to divisions established by the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1493, which prohibited the Spanish from using this route to sail east to Asia. This situation left Spain out of what could be considered global trade in contemporary terms, one that connected the three continents (Europe, Africa, and Asia) that defined the ancient conception of the world. Footnote 22 Therefore, Magellan’s expedition was an imperial response to the political–commercial conditions of the time.

Although Charles V was not completely confident in the success of Magellan’s expedition, he decided to finance it as a way to enter this global trade market. Magellan’s proposed itinerary for crossing America was the only solution that, in case of success, would give Charles V complete economic and political control over this route. This explains why when Elcano and the surviving sailors returned, Spain almost immediately made political use of its accomplishment.

As a result of the circumnavigation, one can say that, in symbolic terms, for the first time capital circulated across the seas, and, as a consequence, as Sloterdijk says, the country of a merchant ceased to be the centre of business. Footnote 23 The constant circulation of capital and products around the world became the driver of the global economy, supported by speculation about new territories and passages between the oceans that would be ‘discovered’. This explains why islands and spaces such as the straits of Magellan, Gibraltar, or Hormuz became ‘points of intensity’ which brought people, objects, markets, and ideas into contact. Having control over these spots implied direct access to goods and a clear advantage over rivals. For example, after having lived in the Moluccas for years, and having traversed the Strait of Magellan in the first post-Magellan expedition, Andrés de Urdaneta asked Charles V ‘to establish a contract betwixt Maluco and the King of Dema in Java, so that there would be pepper, because this King of Dema hath a lot of pepper in great quantity and is a foe to the Portuguese’. Footnote 25

Figure 1. Johannes Schöner, ‘De Nuper sub Castiliae ac Portugaliae Regibus Serenissimis repertis Insulis ac Regionibus, Joanis Schöner Charolipolitani Epistola & Globus Geographicus, seriem navigationum annotantibus. Timiripae (Kirchehrenbach)’, 1523. Footnote 24

The goal of Magellan’s enterprise was to find an alternative to the Portuguese route to Asia; it not only achieved this objective but also changed the meaning of ‘global’ in the commercial sphere. It allowed international exchanges to be thought of at a truly global level, that is, not only connecting Europe with Asia by way of Africa but also considering a new ocean – the Pacific – and the full extent of the American continent from north to south. Magellan’s discovery of his Strait created a route that was global in the modern sense of the word, connecting all of the planet’s continents and the oceans.

These initial changes were more psychological than material. While the Strait united all the oceans in theory, not all territories were included in the dynamics of exchange. Likewise, the interoceanic passage only fed this global dimension speculatively, that is, it was only used as the basis for hopeful hypothesizing on future intercontinental business opportunities. Footnote 26 In fact, due to the difficulties of navigating the Strait, it was not used for trade throughout the century. Footnote 27 However, the psychological impact of its discovery was great enough that European elites became aware of new possibilities of obtaining wealth and realized the importance of encouraging new explorations around the globe.

The Strait of Magellan as a ‘world-passage’

The discovery of the Strait of Magellan accelerated the conquistadors’ desire to establish themselves throughout the American continent. Before great riches were discovered in the Americas, finding routes across these lands was the main motive for expansion. Footnote 28 Therefore, part of the political–territorial configuration of the Americas must be understood, as Serge Gruzinski points out, with ‘China as a backdrop’. Footnote 29 It should be remembered that the Strait of Magellan was the only way to cross the Americas that did not require unloading merchandise, unlike the transit across the Darien (Panama) and later overland routes through New Spain–Mexico.

The appearance of the southern passage highlighted the obsession of some conquistadors with the East, such as Hernán Cortés, who, in the same decade as Magellan’s voyage, crossed Mexico with the idea of building ships in the Pacific that would take him to Asia. In fact, in order to be part of these new circuits, Cortés even offered to have his ships sail from the western coasts of Mexico to investigate what had happened to Loaysa’s in the Moluccas ships after receiving no news of them. This was the first expedition after Magellan’s circumnavigation, carried out in 1525.

In the meantime, several conquistadors residing in North America decided to approach the Strait by land, and thus discovered many territories previously unexplored by Europeans on the Pacific coasts of America. Pedro de Alvarado, for example, had been interested in exploring the southern territories since 1524, and from there sailing to the Spice Islands. Footnote 30 The south thus became a desired remote territory in America and a stepping stone towards Asia, the ultimate objective.

Alvarado’s subsequent conquests in Central America, together with a long voyage to Spain, prevented him from pursuing his initial idea in the first decade after the Strait’s discovery. He pursued this plan, however, when he learned of the riches found in Peru in 1532. In 1533, he wrote to the King informing him that he had sent a ship south to scout the ports and lands where a fleet could possibly be sent to discover new kingdoms. He would take the horses and soldiers necessary for these discoveries on behalf of the King. Alvarado’s enterprise did not bear fruit due to his clash with the conquistadors of Peru, Francisco Pizarro and Diego de Almagro, with whom he ended up negotiating. He wrote to the King:

…and I promise thy Majesty that, if I live two years, thou shalt know the land and kingdoms from the Strait of Magellan to China, because I have very large ships and two hundred men on horseback and five hundred men on foot, and [you] would not have to commit much of thy royal arms to sail to China, or to another richer and more dangerous place. The first voyage I hope to make shall be to the Straits, which I shall penetrate and secure and populate in the name of thy Majesty. And I may send a ship through it to report to thy Majesty of what is there, and thence other ships may come that shall bring ammunition so that I shall pass yonder. Footnote 31

At a macro level, the problem was how to get across America to the Pacific, and how to create settlements that would facilitate this process, which was emphasized by the Spanish Crown, especially when it became fully aware of the significance of this continent in the circulation and distribution of global wealth. Although the map of American coasts and interiors was not complete, the unveiling of the Strait forced the Crown to generate a reordering that maintained the balance of power among the conquistadors and encouraged the search both for riches in America and for a passage to the East. Almost immediately after the signing of the Treaty of Saragossa in 1529, which we will discuss later, in July of that same year the Crown created American governorships, which preceded the organization of the Viceroyalties created in 1535. New Castile (under Francisco Pizarro) and New León (under Simón de Alcazaba y Sotomayor) were established to demarcate the zones of influence of the Spanish conquistadors. The importance of these governorships from the point of view of global routes is that they were thought of not only in terms of jurisdiction but also in terms of economic concession. In other words, just as they were established to configure American territories, they were also conceived with the hope of trading with Asia.

The Strait of Magellan also became a governorate in its own right. For more than twenty years, it functioned as a concessioned space. Only after 1555, once it became part of the Captaincy of Chile, did it lose this status. The Fuggers, a family of German bankers, was the first to negotiate this concession from 1530 to 1531. Their interest in the Strait demonstrates the new global breadth of trade that was expected to pass through it. However, they gave up the concession despite the long negotiation between the Council and Vido Herll, the Fugger family representative. There were two main reasons for this failure: the King of Portugal pressured not to follow through with the deal and the bankers’ demands were excessive, for they wanted control all the way north to Peru. Footnote 32

Within this scenario of negotiations and disputes among the conquistadors, and also in the heart of the Spanish court, one of the conquistadors who was key in arguing for the commercial and geopolitical importance of this passage was Pedro de Valdivia, who since 1540 attempted all possible means to reach the Strait from Chile. By then, several expeditions to the area had failed, including those of Simón de Alcazaba (1535), León Pancaldo (1538), and Francisco Camargo (1540). Valdivia obtained the province of Nueva Toledo (Chile), but this extended only to 41° south, far from the 52°–53° of the Strait. Therefore, in 1539 he associated with Pedro Sánchez de la Hoz, who controlled lands further south. Footnote 33 Their disagreements, lack of soldiers and resources, and indigenous resistance on their path towards the south prevented any significant progress. In spite of this failure, Valdivia was a key figure in promoting the Strait as a global connector until his death in 1553. This may be seen in the constant missives he wrote to both Charles V and Prince Philip, explaining the three reasons why the Strait of Magellan should be navigated and controlled:

First, because thy Highness shall have all this land and the South Sea as part of Spain, and nay one shall dare to do aught that he should not; second, because all the commerce of the spices shall be very close at hand, and third, because ‘twill be possible to discover and populate that other part of the Strait, which, as I am privy, is a very good land…. Footnote 34

Valdivia’s words succinctly summarize the geopolitical value of the Strait, and not only as a corridor for trade: Valdivia raises the issue of taking possession of the region to prevent another European empire from settling there. As of 1550, the lands south of the Strait began to be coveted and represented cartographically by Spain’s enemies. Footnote 35 My interpretation is that Valdivia’s real intention was to create a new end of the world south of the Strait, that is to say, to install a new platform for global exchange in the name of the Spanish Crown. This is attested by the fact that, following his arrival in Chile, Valdivia sought to rename the area of his jurisdiction as the ‘New Extreme’. Footnote 36 In fact, the cities he founded began to be referred to in letters and reports as part of the ‘governorship of the New Extreme’, which in some cases was referred to as Nueva Extremadura.

His geopolitical project would be located in the Strait rather than in Chile. The cities that he founded, like the capital Santiago, were only a first step: ‘So, thy Majesty should know that this city of Santiago del Nuevo Extremo is the first step to build others, and to continue populating by means of these cities all this land to the Strait of Magellan and the Atlantic’. Footnote 37 Valdivia thus displays how the Strait of Magellan was used as a platform to speculate on global commerce. At the same time, he affirms how this global scale works without the continental or local one. In this sense, the Strait is a place that shows how globality works in stages, through itineraries and the control of specific circuits.

These considerations also show how the Strait became part of the process of American territorial configuration, creating differences and delineating the political powers of different actors. We can see a clear example of this in a case contemporary to Valdivia: pilot and trader Andrés de Urdaneta, recognized for having established the trade route between Acapulco and the Philippines in the 1560s. Around 1545–1550, he wrote to Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza y Pacheco, recommending how to proceed with the spice trade. His main idea was to block the Strait of Magellan, which the Crown still believed to be the best passage between the oceans, considering it ‘uninhabitable’ and unprofitable for commercial and political affairs. He was a legitimate authority on the matter, since he had sailed through the southern zone as part of Loayza’s expedition of 1526, voyaging from there to Asia. To achieve his objective, he listed the difficulties of the passage through the southern strait (difficult navigation, extreme climate) and the advantages of the ports and rivers of New Spain for moving merchandise and equipping ships. Footnote 38

One of the things he emphasized was that New Spain was a place that made it possible to imagine global commercial routes and that it could be a ‘world-passage’ like the Strait of Magellan. He detailed the quantities of products, particularly cloves and nutmeg, which the Portuguese extracted from the Moluccan and Banda islands, later to be taken to India and Hormuz, where they were bought by ‘Turks and Moors and Jews and Armenians’ who then took them to Constantinople. Footnote 39 He sought to awaken interest in those places that belonged to the Spanish but which they still did not control, such as the Celebes (today Indonesia), which had cinnamon, ginger, and pepper. He promised that the ‘royal revenues of his majesty’ would increase and that Spain would acquire outlets for trade from which they were then excluded. All this, without thinking of the advantages of approaching China. Footnote 40

He also tried to show the spiritual advantages this course offered. He presented New Spain as a platform for the global transmission of Christianity, from which to build a more dynamic and wider circuit to spread the faith and confront Islam, one of the problems they would face in Asia: ‘and the most important thing, which shall be to attract many thousands of infidels to the knowledge of our holy Catholic faith, halting the steps of the perverse Mohammedan sect that is spreading through those lands very freely’Footnote 41 .

A new way of inhabiting the globe

In 1518, a year before setting off on their voyage, Magellan and his partner, Cristobal de Haro, presented to Charles V the idea of sailing through the southern part of America in search of a passage to the East. After analysing the advantages of supporting this venture and the Crown’s potential profits, the King took complete control of it. He realized that such a passage would allow Spain to enter the spice trade as a protagonist: the expected benefits of sending a fleet to explore the region outweighed the risks. Footnote 42 Some present at the meeting, such as the Emperor’s secretary, Maximilian van Sevenbergen, better known in Spanish as Maximilianus Transylvanus, reported that Charles V offered De Haro and Magellan possession of all the lands and islands they discovered, as a reward for the dangers and labours they would undergo on the voyage. The family and commercial connections of both, including their association with families such as the Fuggers, who had financially supported the investiture of Emperor Charles V and who also had economic interests in Asia, were important in influencing the Emperor’s positive response to Magellan’s proposal. Footnote 43

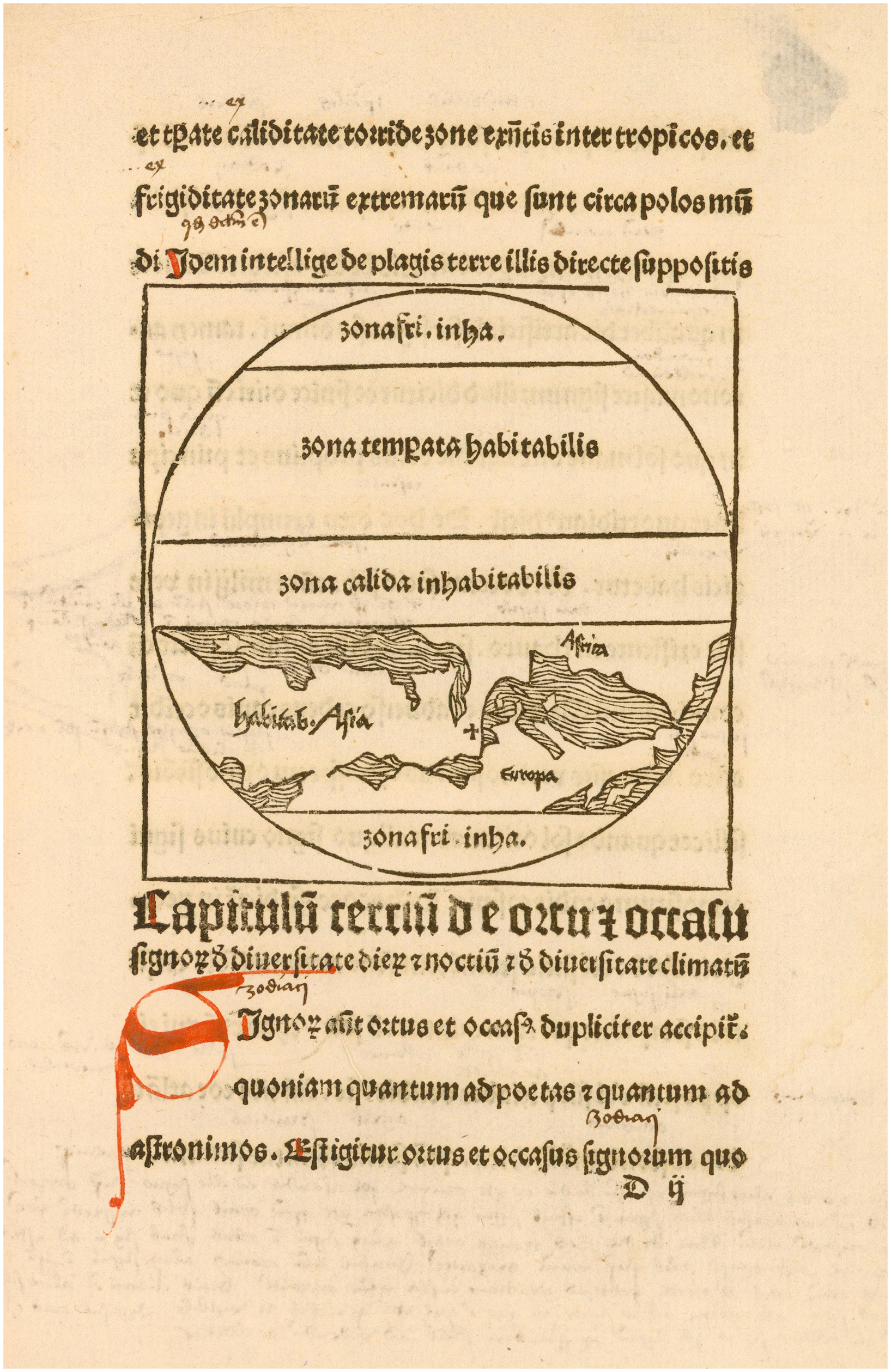

The route proposed by Magellan and De Haro challenged essential geographical, philosophical, and theological assumptions, and initially at least this was a barrier to its implementation. Transylvanus commented that the court considered the idea ‘difficult and vain’. Although they did not consider it ‘serious or impossible’ to reach the ‘other hemisphere’ by sailing west, they were concerned that it would not be possible to sail or cross to the other side of America, due to God’s ‘ingenious nature’ of creating the world. Some members of the court followed an ancient geographical tradition that claimed that the sea did not connect the eastern and western parts of the earth. Claudius Ptolemy’s map of a closed Indian Ocean was still very relevant, the Pacific remained unknown, and some believed in the uninhabitability of certain places due to extreme climatic conditions. Until then, based on the ideas of classical geographers, it was thought that the equatorial zone was not just hot, but uninhabitably hot, and the northern and southern extremes uninhabitably cold. For those nearest the poles, it was not just the cold that was problematic but also the long nights that could last for months. Footnote 44

Figure 2. Globe with habitable and uninhabitable zones, from Johannes de Sacrobosco, Sphaera mundi (Leipzig: M. Landsberg, 1494). Footnote 45

Magellan’s proposal denied the validity of both of these geographical notions imposed by antiquity and gave a solution ‘to both a geopolitical encirclement and a cosmographic perplexity’. Footnote 46 In fact, according to Bartolomé de las Casas, who was also present at the meeting with the King, Magellan confidently declared that, thanks to Portuguese voyages, the falsity of the Torrid Zone had already been proven: ‘I was in the Mina Castle of the King of Portugal, which is near the equator, and so I have witnessed that ‘tis not uninhabitable as they say…’. Footnote 47 In the same way, the notes sent by the Pinzón brothers – famous navigators who also accompanied Columbus – to the court from southern Africa may have influenced Magellan. As Peter Martyr comments in De Orbe Novo, they distinguished certain changes in the arrangement of the stars and the horizon, indicating that something could exist beyond the known zones:

When I asked these sailors if they could see the Antarctic pole, they replied that they had not observed any star similar to those of the Arctic pole identifiable near the other pole. On the contrary, they privy me that there were very different stars and a band of vapour obscuring the horizon. Footnote 48

Magellan promoted a new conception of habitability, making an unknown area appear inhabitable. Regarding the southern zone, he indicated, in agreement with Transylvanus, that it had ‘the things necessary for the sustenance of human life, as there was an abundance of firewood for heat, and many oysters and shellfish, and very good fish of various kinds, and very healthy spring waters’. Footnote 49 Antonio Pigafetta, who wrote a first-hand account of the voyage, referred to the abundance of sardines and herbs, such as celery, that the crew members ate for days in the Strait, declaring that, ‘Methinks there is nay more beautiful territory in the world and better strait than this’. Footnote 50

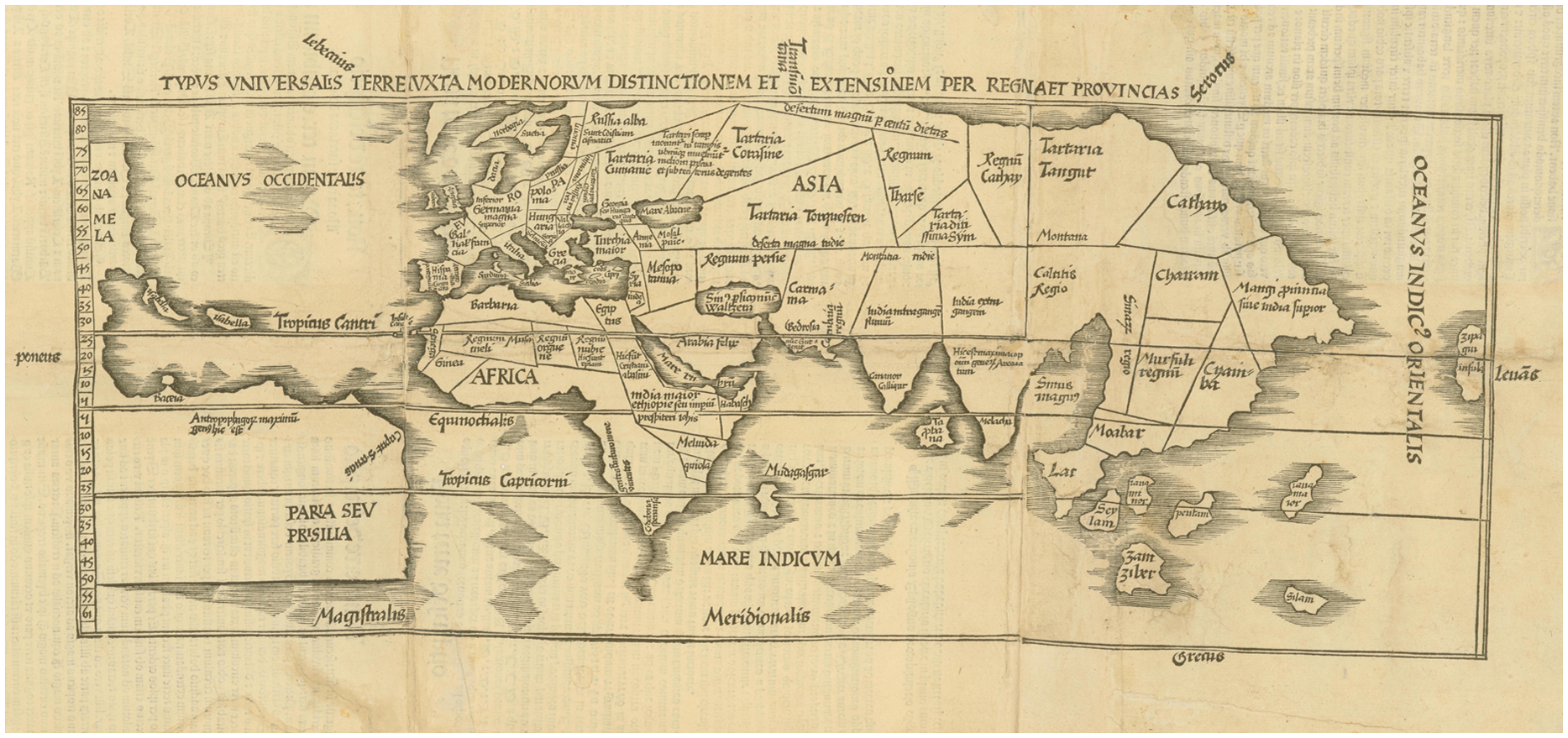

The expedition also modified earlier notions of habitability by changing ideas about distances and meanings that Europeans had assigned to the world through the products and merchandise associated with distant regions. Footnote 51 The spices of the eastern Indian Ocean functioned as the limit of their known world and served as a reference point for understanding this rupture. Magellan’s enterprise made it clear that the location of the East and its distance from Europe, coming from the west, was different from initial assumptions based on classical geography. Likewise, his route revealed unknown locations that did not appear on any map. Maximilianus Transylvanus wrote that the ships financed by Charles V had gone ‘to that strange world, and for so many unknown centuries until now, to seek and discover the islands where spices originate’. Footnote 52 The route of the expedition, first passing through the Torrid Zone and then across the Pacific Ocean, rendered obsolete the world’s ancient division. The impression of Magellan and his crew during their voyage across the Pacific was that they had crossed a ‘…very spacious and unknown sea with the intention of sailing along that route until we were again in the Torrid Zone, and thus sail to the west to arrive in the east’. Footnote 55

Figure 3. Macrobius, world map in Commentary on the Dream of Scipio, from Macrobius Aurelius integer: nitidus (Paris: V[a]enundatur ab ipso Iodoco Badio Ascensio, 1519). Footnote 53

Figure 4. ‘Typus universalis terre juxta modernorum distinctionem et extensionum per regnaet provincias’ from the Margarita Philosophica of Gregor Reisch (Strasbourg: Johann Grüninger, 1515). Footnote 54

Geographers and other authorities came to understand this new size of the globe by questioning and refuting ideas elaborated in antiquity, although not without recurrent contradictions. Footnote 56 But the ‘traditional moral or epistemological opposition’ could not withstand the great volume of new information that had begun to flood the courts since the voyages of Columbus. Footnote 57 Transylvanus was among the first to argue that the ancients had written things ‘fabulous and not true’ which could be refuted by the experiences of the voyage completed by Elcano. Footnote 58 Ptolemy, whose influence was tremendous, had described only half of the world, that is, 180° of longitude, the distance from the Canary Islands in the west to Catigara in the east (in what is now Vietnam). Footnote 59 He knew that the world was made up of 360°, but he had no knowledge of the geography beyond the 180° that he depicted. To think about the 360° of longitude necessary for circumnavigation required integrating new skies and stars, Footnote 60 as understood in those years by scholars like Copernicus. Footnote 61

The epistemological and political upheaval that swept Europe with the Victoria’s return quickly channelled into a political stance. Talks between the Pope, the Spanish, and the Portuguese about the location of the Moluccas Islands after the ship’s voyage, which sought to replace the division of the world between these two powers recognized by the Treaty of Tordesillas (1493), were the first to put the issue up for debate. Footnote 62 The fact that the Pope was involved in these discussions shows how the Church participated in this process of secularizing the concept of the ecumene, which began in the fifteenth century. Footnote 63 Between 1523 and 1529 – the year in which the Treaty of Saragossa was signed, which would put an end to the initial disputes generated by the first circumnavigation of the globe – the European kingdoms and Rome held various meetings to discuss the new division of the world. The Junta de Badajoz-Elvas (1524) was one of them, and it brought together Portuguese and Spanish experts to discuss the cosmographic changes generated by the circumnavigation. Spain brought renowned cosmographers such as Diego Colón, Juan Vespucci, Sebastian Cabot, and Juan Sebastian Elcano. Columbus’s son, Diego, clarified the challenge of measuring this vast new world:

First of all, as the division to be made is of an unknown quantity, ‘twill be necessary to ascertain and verify its greatness, which must be done in one of two possible ways: by measuring the whole globe or body to be divided, or by truly knowing the part of it that corresponds proportionally to the other, whose greatness is shown to us by the sky, which the wise men divided into 360 parts or degrees Footnote 64 .

Clearly, an imperial appetite grew in all the European kingdoms – particularly amongst the elites – to carry out similar enterprises in the new Southern hemisphere, which had been opened by Tierra del Fuego, and in newly discovered territories in the Pacific Ocean. This European ‘world-consciousness’, as we can see with particular regard to America, manifested itself in the desire for domination and generalized territorial occupation on a global scale during the sixteenth century.

The circumnavigation as a modern universal event

Charles V sought to position Spain as a protagonist of this new global dimension, which broadened the conception of the world, incorporating new territories and new connections, and which questioned the ancient conventions that Europeans had believed in for centuries. Therefore, cosmographers, theologians, and chroniclers sought to mark the historical impact caused by Magellan’s voyage. Transylvanus and Peter Martyr in his fifth Decade, published in 1523, referred to the historical importance of the expedition, indicating that it surpassed any of the voyages of the Greeks. Footnote 65

The new awareness of the world and the geographical revolution heralded by the circumnavigation promoted an unprecedented restructuring of historical thought. Therefore, the question arises whether there was a new ‘regime of historicity’, since the manuscript evidence shows that this revolution brought new ways of translating and organizing experiences. Footnote 66 This was expressed in various ways by the thinkers of the time, for example, in the epoch-making function of Magellan’s voyage. As seen in the first chapter of volume I of the Second Part of Fernández de Oviedo’s General History of the Indies:

Mine own conscience requires and cites me to begin the second volume of these histories (concerning the Tierra-Firme) with Admiral Christopher Columbus, pioneer and author and starting point of all the discoveries of the Indies…. However, the order of history requires and cites me not to begin with the admiral, but rather with Captain Ferdinand Magellan, who discovered that great and famous southern strait in the Tierra-Firme, so that we can relate a more orderly account of the settlement of that land and its geography and limits and latitudes. Footnote 68

Figure 5. ‘Carta universal en que se contiene todo lo que del mundo se ha descubierto hasta ahora, Diego Ribero cosmografo de Su Magestad. Año de 1529, Sevilla’. Footnote 67

This possible change in the regime of historicity was also expressed in the global scope expected of the stories that emerged from this event. The circumnavigation made it possible to add a truly global dimension to the discipline of history up until then in Europe. Footnote 69 According to Gruzinski, introducing this voyage as the first event in the history of the globe was a way for European kingdoms and elites to fabricate historical time and impose it as a universal idea on other societies around the globe. Footnote 70

Over the years, the Victoria ship and the figure of Juan Sebastian Elcano became icons to mark the leap forward from antiquity into a new age. Clear examples can be found in the texts of major chroniclers, such as Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo and Francisco López de Gómara. Footnote 71 The latter dedicated an entire chapter to the subject: ‘Jason’s ship, the Argos, which they placed in the stars, sailed very little in comparison with the Victoria […] The detours, dangers and labours of Ulysses were nought compared to those of Juan Sebastián’. Footnote 72 For this author, realizing that the world was fully habitable was only possible, thanks to the Spanish voyage that had refuted ancient speculation:

And so, experience is contrary to philosophy. I wish to overlook the many ships that regularly travel betwixt Spain and the Indies, and speak of only one, the Victoria, which rounded the whole sphere of the earth, and, touching the lands of both antipodes, declared our wise antiquity to be ignorant. Footnote 73

One of the most influential people of the court, jurist Ginés de Sepúlveda, in Book I of De orbe Novo, insisted on this condition: ‘in our time, on the other hand, there is nay region that the excess of heat or cold maketh uninhabitable: on the contrary, ‘tis inhabited by many men and other living beings, because the orb hath been explored thanks to the experience of the Scythians and the navigations of the Spaniards’. Footnote 74 Seventy years after Magellan’s passage through the Strait, the Jesuit José de Acosta, one of the most influential religious men in the Spanish court, celebrated the reversal of the world’s uninhabitability and the conquest of its vast circumference, which was now subject to human transit and measurement:

Who will not confesse but the ship called the Victorie (worthie doubtlesse of eternal memorie) hath wonne the honor and praise to have best discovered and compasssed the round earth, yea, that great Chaos and infinite vast which the ancient Philosophers affirmed to bee under the earth, having compassed about the world and circled the vastnesse of the great Oceans. Who is hee then that will not confesse by this Navigation but the whole earth (althouh it were bigger then it is described) is suiect to the feet of man, seeing he may messure it? Footnote 75

Despite the new perspectives and discoveries brought on by this event, the stories were told within the traditional parameters of universal history. In them, the rest of the world was identified, but as part of the way to understand how time and space in the sixteenth century continued to connect with classical antiquity. Proof of this is that there were constant historical references to the ancients who had defined the European universe in discussions on global processes such as habitability. It was important to compare what the Spaniards did with the accomplishments of the Greeks or to find ancient historical references to the new discovered places. The world was seen through a European lens. Footnote 76 This self-absorption was a way of orienting oneself through the vertigo of radical changes that were occurring, the anxiety of expansion, and the lack of control over this process.

Faced with this scenario, one might wonder whether topics such as habitability functioned as a construct to interpret and transmit this universal European history, presenting it as a pillar of the new global history. It is no coincidence that until the first half of the seventeenth century European general histories maintained the medieval tradition – inaugurated by fifth-century historian Paul Orosius – of opening with a description of the habitable world. Perhaps understanding the milestones that globalize a place and, at the same time, Eurocentricise it is also a clue to see how a space became global in the sixteenth century.

Resources: the new ‘climate’ for considering habitability

‘Our intent to locate the magnificence of this earth may seem a vanity, but ‘tis no difficult task, for we find it in the middle of the world. Its confines are the sea which surrounds it. I know not how to describe it in fewer or truer words’. Footnote 77

The discovery of the Strait of Magellan made it possible to imagine the American continent as an extension of Europe, and also a continuous world. Footnote 78 Acosta speaks of a world that embraces itself, thanks to God the redeemer and the recent explorations, something that was alien to ancient thinkers: ‘But is sufficeth for our subiect, to know that there is a firm Land on this Southerne part as bigge as all Europe, Asia, and Affricke; that under both the Poles we finde both land and sea, one imbracing an other. Whereof the Ancients might stand in doubt, and contradict it for want of experience’. Footnote 79

Throughout the century, the most important Spanish thinkers considered the southern zone of America as an area of particular importance and, specifically, the Strait of Magellan as a land that united the poles. For example, in the proem of book XXXVIII of his Historia General y Natural de la Indias (1557), the first chronicler of America, Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, alluded to this process in a similar way and went so far as to imagine the continent as being united with Europe:

I have wished to place hither the last book of this second part, so as to refute the conceits of the ancient cosmographers and writers, who believed that the earth below the poles is uninhabitable; and from what we observe and now know of the sea from those who have sailed it, and from what a modern and learned man teaches us through his writings and experience and painting, we can see the contrary. And because until the end of mine previous book, I have described the great coast of the Tierra-Firme from the Strait of Magellan to the land of the Labrador, which is to the north or northern part, and which allowed me to finally understand how it joins with Europe. Footnote 80

To show the novelties that the American continent contributed, the natural histories and universal cosmographies published in Spain had to explain the arguments of classical authors in order to show that those novelties really were new and different. The new habitability could only be distinguished if the old conception was clarified, although this could also be interpreted as part of the universal–imperial exercise of historically connecting spaces to present them as their own. Francisco López de Gómara, like many others, in the first chapter of his works had to explain the parts of the world that were uninhabitable according to ancient thinkers:

Wanting to demonstrate that the greater part of the earth is uninhabitable, they draw five strips in the sky, which they call zones and which regulate the orbit of the earth. Two are cold, two are temperate, and one is hot. If thou want to know the disposition of these five zones, place thy left hand betwixt thy face and the sun when it sets, with the palm facing thee, as the grammarian Probo taught; keep thy fingers open and extended, and looking at the sun through them, thou can see that each one is a zone: the thumb is the cold zone towards the north, which because of its excessive cold is uninhabitable; the next finger is the temperate and habitable zone, where we find the tropic of Cancer; the middle finger is the Torrid Zone, which men have thus named because of its roasting and burning heat, and ‘tis uninhabitable; the ring finger is the other temperate zone, the tropic of Capricorn; and the little finger is the other cold and uninhabitable zone, in the south. Knowing this rule, then, thou shalt understand the habitable or uninhabitable parts of the earth, as according to these men. Footnote 81

To mark these differences, the Torrid Zone was also discussed, since, as José de Acosta had indicated, it was the climatic conditions in the tropical zones that had prevented him from imagining the possibility of a connection between the poles. Footnote 82 As the Jesuit himself points out in reference to the Aristotelian ideas that had predominated on this point, ‘Reason teacheth us that her boundaries and limits, and yet all this habitable earth cannot be united and ioyned one to the other, by reason the middle Region is so intemperate’. Footnote 83

Several Spanish agents attempted to exculpate ancient philosophers such as Aristotle and Ptolemy. It was not a definitive break with the old but a contrast and a selection of characters and arguments that could continue to be useful for imperial purposes. Bartolomé de las Casas indicated that Ptolemy and Avicenna, ‘whom God singularly perfected in the secrets of nature’, had advanced the possibility of inhabiting the ‘middle part’ or tropical zones. As the Dominican friar said, in these discussions the American continent and the southern zone appear as proof of a new understanding of these areas: ‘All of which is now well proven in our Indies, and some of which I myself, the author of these lines, have experienced’. Footnote 84

As Las Casas indicates at the end of the paragraph, the American experience functions as a spyglass with which to observe this new habitability. Footnote 85 Las Casas writes: ‘…for there are already many of us who have been there and in some parts we have seen the most pleasant and softest habitat, and in others there is so much snow that ‘tis hardly habitable, and in others ‘tis very hot, but not so hot as to make it completely uninhabitable’. Footnote 86 He clarifies that it is not the atmospheric conditions that determine the habitability of a place, but the amount of work involved in obtaining the necessities of life:

…and so we must understand what the ancients said about there being some places or regions in the world, such as the areas near the poles, which because of cold, and the torrid or equinoctial zone, which because of heat, could not be inhabited, namely, with difficulty and too much work for the inhabitants, but not that they could not be inhabited at all. Footnote 87

Gómara makes a similar observation, indicating that, ‘there is nay land depopulated by too much heat or too much cold, but rather by want of water and food’. Footnote 88

These passages show us how the Earth has become a wide-open horizon, in which the climate – as conceived by ancient and medieval authors – ceases to be the main factor when considering places for future habitability. This was also transmitted by some non-Spanish authors, such as Giovanni Battista Ramusio, who wrote: ‘‘tis clear that this entire terrestrial globe is marvellously inhabited, and there is nay empty part of it, for neither heat nor cold has deprived the earth of inhabitants’. Footnote 89 In other words, the new climatic experience in the Americas allowed European courts to conceive of every region of the world as potentially habitable, no matter how different its atmospheric conditions, introducing new parameters for the habitable and uninhabitable. Following Bruno Latour, who defines ‘climate’ not only as the atmospheric conditions of a place but also as the natural and material conditions in which human existence develops, we believe that Magellan’s circumnavigation activated a different climatic regime. Footnote 90 Since that voyage, the condition of uninhabitability was ascribed to those places where material (not climatic) conditions would inhibit the extraction or circulation of valuable commodities. Multiple examples of this are recorded in the expedition chronicles of the European conquest of the Americas, which sought to position different metropolitan powers in the southern zone, unimaginable in the previous century.

It is easy to find evidence of this new conception of habitability based on the availability of life necessities rather than climatic zones. The conquest of America and attempts to position European powers in the southern zone allow us to recognize this. For example, in 1539, from the City of Kings, treasurer Manuel de Espinal wrote the King of Spain about the difficulties of the expedition led by Diego de Almagro on his journey to Chile and the Strait of Magellan. He detailed the ‘many difficulties of hunger and cold’ they had gone through and how Gómez de Alvarado, brother of the adelantado Pedro de Alvarado, had left for the Strait by sea, but was forced to return because, a hundred leagues from it, he saw that ‘‘twas an uninhabitable land with many swamps and rivers and few people and ‘twas impoverished’. Footnote 91 Another example presented above was that of the merchant cosmographer Andrés de Urdaneta. In 1554, he insisted that goods brought from the East should pass through New Spain because of its good conditions, unlike those at the southern tip of America: ‘I wish to say that, although the navigation of the Strait was not so dangerous, ‘tis an uninhabitable land, and ‘tis not wise to cross it with such valuable goods as spices’. Footnote 92

The Human Condition in the New World

According to Spanish sources, the circumnavigation also challenged the theological idea that God had not wanted the world to come together and thus divided the planet into ‘realms supposedly within God’s redemptive grace, as well as realms outside it’, Footnote 93 an idea that raised various questions about the human condition. Footnote 94 Once the Torrid Zone was understood as a habitable region for humans, it was necessary to learn who lived there and in other extreme regions. Footnote 95 That is to say, one of the longest geographical debates had to be faced anew: the nature of the antipodes. Footnote 96 This correlation is less surprising than it seems at first, since as Augustin Berque says, we are human to the extent that we recognize ourselves in the antipodes. Footnote 97

Ancient philosophers had proposed that it was impossible to find human life in those extreme zones. In the Middle Ages, the arguments changed: the debate turned to whether the antipodes were de facto inhabited or not. The term ‘antipodes’ designated both the lands and inhabitants of the southern hemisphere and also those of the western hemisphere. Over time, this term came to be used to indicate otherness, and the people called antipodes became a mythological and literary motif. Footnote 98 At the same time, we find this ancient geographical notion challenged by the aspiration of Christianity to reach all parts of the earth. Footnote 99 The possibility of other forms of human life in areas that were considered unreachable, and that did not appear in Sacred Scriptures, was a recurrent topic to prove that it was impossible to live in those regions. Footnote 100 Those who inhabited them could hardly be descended from Adam and, therefore, there could be no gospel or redemption in them. In case there was some form of human habitat, it would be by deformed beings, monstrous ‘men who have their feet contrary to ours’, as Acosta said before the circumnavigation’s success. Footnote 101

Therefore, after the circumnavigation, thinkers were forced to explain the existence of lands in the western and southern parts of the world that were not mentioned in the Scriptures. Were these lands a part of God’s kingdom? And related to the nature of the human inhabitants: were they Noah’s children, or were they monsters or some other type of creature? Could they or could they not be considered descendants of Adam? I believe that this set of questions – which never ceased to be asked about distant peoples since the Middle Ages – silently directed some of the European characterizations of the different types of ‘peoples’ living around the globe in cartographic and cosmographic contexts. Footnote 102

Spanish authors tried to generate a coherent account of this whole process through a selective reading of texts by various ancient authors. Gómara pointed out that authors like Strabo and Macrobius and some Christians like St. Clement and Albert the Great did not believe that there were antipodes, because it was impossible to find men in the southern hemisphere, and that if there were any, it was impossible for them to pass across the Torrid Zone and its great ocean. Like many, he tried to exculpate figures such as St. Augustine, who did not believe in the antipodes, by pointing out that it would have been a scandal for him to say otherwise, despite what he thought. The absence of southern lands in Sacred Scriptures prevented him from justifying this, according to Gómara. Footnote 103

Revisiting the theme of the antipodes was also a way to renew Christianity’s global mission and to explore the history of the newly discovered territories. It also made humans coexist with and discursively inhabit the totality of terrestrial space. Gómara himself speaks of three types of ‘neighbours of the world’. For this, he uses Greek descriptions of the inhabitants of the different parts of the world, perioeci, antoeci, and antipodes. The southern zone appears as a reference that allows us to understand this new human categorization:

And whoever looks at the image of the world on a globe or map shall clearly see how the sea divides the earth into two almost equal parts, which are the two hemispheres and orbs mentioned above. Asia, Africa and Europe are one part, and the Indies the other, in which we find those who are called antipodes; and ‘tis most absolute that those of Peru, who live in Lima, Cuzco and Arequipa, are antipodes of those who live at the mouth of the river Indus, Calicut and Ceylon, island and lands of Asia…. In addition to the antipodes there are others whom they call parecos and antecos, and these three names include all the neighbours of the world…. The antecos of the Spaniards and Germans are those of Rio de la Plata and the Patagonians, who dwell in the Strait of Magellan. We do not live in opposite lands as antipodes, but in different lands. Footnote 104

A recurring question was how these territories had been settled by people and when. Some renowned cosmographers at the Spanish court, such as Juan López de Velasco, indicated that this had not occurred from Ireland or other northern parts, as some scholars had suggested. For him, it was more plausible that the Old World and the New World had been connected at some point, although ‘now they are not, and that somewhere the sea might have crashed in and made some strait, covering the land across which men and lions, tigers, tapirs and deer, and other animals of these parts had passed’. Footnote 105

The debate about the antipodes and the humans who inhabited them also raised questions about the nature of monstrosity, as Surekha Davies points out: ‘The circumnavigation also marked an ontological seam between two discourse from classical antiquity for understanding human cultural and physical variation: the discourse of monstrous peoples, who fell beyond the purview of regular humanity and civility; and the discourse of contingent human variance in temperament, appearance and capacities in relation to local climatic conditions’. Footnote 106 In fact, Maximilianus Transylvanus, in his letters, ‘demanded’ answers as to where exactly were the monsters of Herodotus and Pliny that for centuries had somehow marked the limits of the world and had remained outside the bounds of the human condition:

Who dare believe that there are Monoscellos (or Stipadas), Spithameos (Pygmies) and others like them who are more monsters than men, which the ancient writers have claimed existed…. these Spaniards of ours, who have now returned in this ship, having gone around the whole world, have never come across, seen, or even heard about in all their travels, that not now or in any time there have been or will be such monstrous men? Footnote 107

This question from Charles V’s secretary foreshadowed the theological–political discussions on categories of humanity and their representations in regard to the American ‘savages’. At the same time, they sought to answer these questions with some of the information gathered during the expedition. Transylvanus was the one who created the imaginary appearance of the ‘last human’, or rather the first of the new era, namely the men and women who lived in the far south of South America. The giant Patagonians, who are linked to the imagery of ancient European mythical giants, became one of the symbols that represented the southern part of America and its inhabitants within the new image of the world that was being constructed. Footnote 108 The fact that they were giants was consistent with the earth’s new grandeur. Footnote 109

Transylvanus’s initial account placed them in the Gulf of San Julián (Atlantic Patagonia) and he described them as enormous humans who ‘put arrows as long as a cubit and a half down their mouths and throats as far as their stomachs’. Footnote 110 Subsequently came the accounts of Antonio Pigafetta and others who made this figure a typical representative of the southern zone of America, especially within Northern European or Protestant cartography. Footnote 111

This icon of the new ‘global south’ also served to mark a distance from the past, from the world described by ancient thinkers. The exploitation of these figures, in the words of François Hartog, marked the physical and temporal distance from ancient conceptions and created meaning in the geographies of the distant reaches of the world. Footnote 112 The term Patagonian was part of a language that revealed a transition in the debate regarding habitable and uninhabitable spaces, indicating the possibilities of living in lands formerly believed uninhabitable. This figure was used to geopolitically differentiate the southern zone of America from other southern areas, such as the Terra Incognita further south. Footnote 113 As Young points out, some territories considered part of the harsh south did not necessarily correspond to the southern hemisphere, rather to spaces where wealth or commodities were imagined. Footnote 114

We believe that the Patagonian was also used as a ‘boundary marker’ in the new framework of inhabitability, not in the sense that his land was uninhabitable but in the sense that very little was known about the American southern zone. Footnote 115 The Patagonian entered the classification, subordination, and moralization of the discovered territories. Footnote 116 In part, as Young says, this was because ‘the early geographies used broad designations of ‘the southern parts of the world’ or ‘the south’ sought to establish a social hierarchy on a global scale”. Footnote 117

The figure of the Patagonian served to promote the imperial desire for European expansion by creating an imaginary dimension associated with the ‘marvellous’ in a land that itself had some marvellous characteristics during this century. This figure condensed and homogenized the differences between the natives of the region, which is expressed in several surviving maps. Footnote 118 Certainly, this is also part of an overlay of one universe of knowledge onto another. The Patagonian made invisible the indigenous people of the area and their epistemic apparatus. There are no detailed descriptions of the Tehuelche, Selk’nam, Yaghan, and Kaweskar groups beyond the question of their height, some remarks about their diet, and some specific encounters with them. Footnote 119

Indeed, in order to describe what they saw, explorers like Antonio Pigafetta described the behaviour of the natives as if they were ‘exotic’ and used references from the European epistemological universe when they did not know how to explain something: ‘The captain called these people Patagones, who have nay other house than huts made with the skin of the aforementioned beasts, from which they live, and they go hither and thither with their said huts, as the Egyptians do’. Footnote 120 In any case, all these notes were brief and anecdotal, despite the fact that these groups offered Europeans knowledge that allowed them to navigate those arduous currents and survive in a difficult climate, unlike any other in the rest of America. There was no interest in understanding how their presence overthrew the conception of habitability reproduced since ancient times.

Although there was an attempt to learn more about these peoples decades later, very little was known about them. There are some records that provide information, such as those from the voyage of Juan Ladrillero (1557–1559), the only explorer who left a comprehensive record of the environmental conditions in the region and who made reference to the indigenous way of life. However, he made these notes in order to facilitate a safe passage between Europe and the Peruvian coast through the Strait of Magellan. He was only interested in these peoples to distinguish the Strait’s entrances and exits, despite the King’s orders to investigate the ‘secrets’ of the territory and describe its inhabitants’ ways of life. Footnote 121 In his sixty-page report, the indigenous peoples, though present, are at the same time hidden. For example, Ladrillero briefly remarks that, thanks to ‘an Indian who was a guide’, they were able to travel to the lands south of the Strait, where they recognized many islands and high ‘snowy mountains’. Footnote 122 In fact, this emphasis on the European epistemic universe to the detriment of the contributions made by the natives was maintained in the following centuries. It was only in the nineteenth century that scientific interest in these groups was awakened and they began to be studied.

Conclusion

The discovery of the Strait of Magellan and the subsequent circumnavigation was an event that created a different horizon for navigators. They crossed the limits of the old ecumene and became aware of the ‘terrestrial globe’. We can recognize this transformation through the two facets that changed the course of European expansion, which cannot be separated from each other. Both installed the ‘global’ scale in European courts. First, there is the commercial perspective, which challenged the spatial conceptions prevalent until 1520, opening an alternative route to the East, which had up until that point been dominated by the Portuguese passage around Africa, consolidating their near monopoly on trade with Asia.

The impact of this new route through the Strait was principally at the psychological–discursive level. The route as such was little used. This was due in part to the fact that Europeans were unable to establish themselves in the area because of its remoteness, and in part to the maritime and climatic conditions that made it difficult to traverse the Strait. Regardless, Spain presented the discovery of the Strait as an event that united all of the seas, an event in which America, from its extreme north to its extreme south, and the Pacific Ocean, should be considered in order to understand the commercial opportunities of new connections, as well as the epistemological challenges brought on by the new image of the world.

In this commercial aspect, we also find a new geopolitical dimension. As of 1520, a new set of political–economic provisions and tactics, both State and private, and in some cases military, began to operate within European kingdoms in regard to the territories where they had little influence. In particular for the southern area, the interest in obtaining commercial revenues prompted kingdoms such as France and England to send various expeditions to the region, the most successful being that of Francis Drake, who managed to navigate the Strait in 1578. Among these provisions and tactics, speculation helped the conquistadors imagine riches – the mythical City of the Caesars, for example – and to imagine values or easy ways to move merchandise from one continent to another, as we saw in the case of Urdaneta.

The second facet is related to the new way of perceiving ‘open’ space that allowed a new understanding of places such as the southern zone of America and generated a new vision of others, such as the tropics. The emergence of the southern zone activated a series of epistemological discussions about the meaning of habitability. Indeed, we believe that the emergence of this region was key in the secularization of habitability during this century, transforming its biblical and classical images into new descriptions based on its geographical and political condition, which served imperial purposes at the beginning of early modernity. This was demonstrated by the case of some conquistadors whose accounts showed how habitability was no longer determined by atmospheric conditions, but depended on the presence of the materials necessary to exploit the territory.

Funding Statement

This article is part of a project funded by two different institutions, John Carter Brown Library (Jeanette D. Black Fellowship) and the ANID-FONDECYT Project No 1220219: “The epistemological, historical and territorial construction of the Southern Zone as a Natural Laboratory: scientific agendas, knowledge networks and global imaginaries”.